Abstract

Background

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a neurodegenerative disorder pathologically characterized by intracellular tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein distributed throughout the neocortex, basal ganglia, and brainstem. A genome-wide association study identified EIF2AK3 as a risk factor for PSP. EIF2AK3 encodes PERK, part of the endoplasmic reticulum’s (ER) unfolded protein response (UPR). PERK is an ER membrane protein that senses unfolded protein accumulation within the ER lumen. Recently, several groups noted UPR activation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple system atrophy, and in the hippocampus and substantia nigra of PSP subjects. Here, we evaluate UPR PERK activation in the pons, medulla, midbrain, hippocampus, frontal cortex and cerebellum in subjects with PSP, AD, and in normal controls.

Results

We found UPR activation primarily in disease-affected brain regions in both disorders. In PSP, the UPR was primarily activated in the pons and medulla and to a much lesser extent in the hippocampus. In AD, the UPR was extensively activated in the hippocampus. We also observed UPR activation in the hippocampus of some elderly normal controls, severity of which positively correlated with both age and tau pathology but not with Aβ plaque burden. Finally, we evaluated EIF2AK3 coding variants that influence PERK activation. We show that a haplotype associated with increased PERK activation is genetically associated with increased PSP risk.

Conclusions

The UPR is activated in disease affected regions in PSP and the genetic evidence shows that this activation increases risk for PSP and is not a protective response.

Keywords: Progressive supranuclear palsy, PERK, Unfolded protein response, EIF2AK3, Alzheimer’s disease

Background

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a late-onset neurodegenerative movement disorder clinically characterized by vertical gaze palsy, poor balance and frequent falls, as well as cognitive impairment and dementia [1,2]. The primary symptoms of PSP are consistent with the observed neuropathology, mainly neuronal degeneration in the brainstem, particularly the pons and medulla [3]. Postmortem pathological analysis of these brain regions in PSP patients reveals numerous intracellular neurofibrillary and glial tangles comprised of hyperphosphorylated protein tau (htau). Thus PSP, along with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), belongs to a group of disorders collectively known as tauopathies, as all these disorders show abundant tau aggregates or inclusions as prominent neuropathologic features. Other tauopathies include frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and Pick’s disease [4]. Some mutations in the gene MAPT, which encodes tau, can result in a PSP phenotype [5-9], while common variants in the MAPT region are associated with PSP susceptibility [10-13]. Thus, genetic studies as well as our data here indicate that tau is clearly linked to PSP pathogenesis.

Schellenberg and colleagues recently completed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for PSP risk loci [10]. One of the genes identified was eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 3 (EIF2AK3), which encodes the protein pancreatic endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). PERK is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane protein that acts as a stress sensor in the ER unfolded protein response (UPR). In addition to PERK, there are two other stress sensors (both of which are also ER membrane proteins): inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6; [14]).

All three arms of the UPR activate when the chaperone immunoglobulin binding protein (BiP), normally bound on the luminal side of each protein, dissociates in order to aid in the folding of accumulated unfolded proteins in the ER lumen. Dissociation of BiP from PERK and IRE1α facilitates their activation by promoting homodimerization and trans-autophosphorylation [15]. ATF6 is then activated via a cleavage event and subsequently translocated from the ER to the nucleus [16]. Each of the three branches of the UPR initiates discrete signaling cascades in response to the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER lumen. The role of the UPR is to restore protein homeostasis by upregulating chaperone production [17,18], attenuating translation, promoting degradation of misfolded proteins via ER-associated degradation (ERAD; [19], and promoting autophagy [20]. Prolonged ER stress can trigger apoptosis [14,21].

The PERK arm of the UPR acts primarily on translation. When PERK is activated (thus becoming phosphorylated PERK, or pPERK), a kinase domain on the cytosolic side of the protein phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α or peIF2α when phosphorylated). peIF2α is a less active form of the protein, and its decreased efficiency slows general translation initiation and promotes translation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). ATF4 promotes transcription of genes that enhance amino acid uptake and protect against oxidative stress [22]. Elements of the PERK pathway are also involved in regulating autophagy, a process that degrades misfolded proteins [23,24]. Thus, genetic variation that results either in alteration of PERK protein function or significant changes in the amount of PERK would perturb several crucial stress-response pathways.

Several neurodegenerative disorders, including PSP, are characterized by pathological aggregates of misfolded proteins in the brain. Previous work showed that the UPR is activated in post-mortem AD brains [25], as well as in the brains of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau inclusions (FTLD-tau) [26], PD [27], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [28,29], and multiple system atrophy (MSA) [30]. Nijholt et al. (2011) reported evidence of UPR activation in the hippocampus and, to a lesser extent, the locus coeruleus and putamen of PSP patients.

We investigated activation of PERK and eIF2α in postmortem brains from subjects with PSP and AD, as well as from normal elderly subjects. We used antibodies that recognize the phosphorylated species of PERK and eIF2α, i.e. the activated forms of these 2 proteins (pPERK and peIF2α, respectively). Our primary goal was to investigate the brain regions most affected by tau pathology in PSP. We searched for evidence of PERK and eIF2α activation in the pons, medulla and midbrain, regions affected in PSP, in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, which are regions affected in AD, and in the cerebellum, a brain region which is relatively spared in both diseases, although the deep cerebellar nuclei and cerebellar cortex may harbor modest amounts of tangles and plaques, in PSP and AD, respectively. We also looked at PERK and eIF2α activation in young controls to determine if ER stress is activated in normal aging. Our results indicated that PERK and eIF2α activation pllels the pattern of neuropathology in PSP and AD. In normal hippocampus, activation increases with age and correlates with tau but not Aβ amyloid pathology. We also examined coding haplotypes that were previously shown to affect PERK activation [31]. We found that the haplotype that corresponding to the highest PERK activation is in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the high risk allele of the top PSP GWAS marker, indicating that UPR activation increases PSP risk and is not a protective response in PSP.

Results

The PERK arm of the UPR is activated in PSP

To determine whether the UPR is activated in PSP, we stained post-mortem human brain tissue from PSP and AD patients as well as normal elderly controls using antibodies against pPERK and peIF2α, the activated forms of these proteins. We chose six brain areas to stain for PERK and eIF2α activation: the pons, medulla, and midbrain (affected in PSP), the hippocampus and frontal cortex (affected in AD), and the cerebellum, which is relatively spared in both diseases.

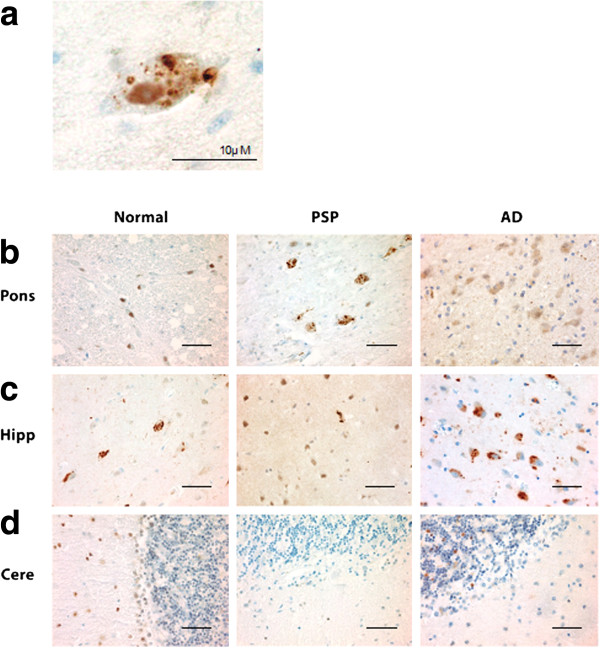

In PSP cases, of the regions tested, the pons, medulla, and midbrain demonstrated the highest degree of pPERK and peIF2α staining (Figures 1b, 2b, 3a-c, and 4a-c) as measured by number of cells showing staining per field (Additional file 1: Figure S1). These are the brain areas most affected by tau pathology in PSP. pPERK and peIF2α staining was punctate and cytoplasmic with some non-specific nuclear staining (Figures 1a and 2a), a pattern observed by others in AD and PD [25,27]. In the pons, all PSP cases showed some cells positive for both pPERK and peIF2α. pPERK was observed in the medulla and midbrain in all but one case for each region. For peIF2α, all cases showed positive cells in the medulla and all but one case showed positive cells in the midbrain.

Figure 1.

pPERK is activated in PSP, AD, and normal brain. a. Example of a cell with pPERK immunoreactive puncta in the pons of a PSP case. b-d. Representative fields showing pPERK staining of pons, hippocampus, and cerebellum in normal, PSP, and AD cases. Scale bars are 50 μm unless otherwise indicated.

Figure 2.

peIF2α is activated in PSP, AD, and normal brain. a. Example of a cell with peIF2α puncta in the pons of a PSP case. b-d. Representative fields from peIF2α staining of pons, hippocampus, and cerebellum in normal, PSP and AD cases. Scale bars are 50 μm unless otherwise indicated.

Figure 3.

Frequency of pPERK staining scores in PSP, AD, and normal brain. Distribution of pPERK staining scores. +++ = widespread activation, ++ = moderate activation, + = diffuse activation, R = rare activation, - = no activation. Y-axis indicates number of cases with a particular pPERK staining score. All P-values obtained using Fisher exact test. a-c. PSP cases had the strongest pPERK staining in the pons (PSP vs. Normal: p = 3.8E-9) and the medulla (PSP vs. Normal: p = 6.1E-7), as well as moderate staining in the midbrain (PSP vs. Normal: p = 6.0E-6) which was affected in all PSP cases. d-e. AD cases had the strongest pPERK staining in the hippocampus (AD vs. Normal: p = 0.0006) and moderate staining in the frontal cortex (AD vs. Normal: p = 4.1E-5) both of which were affected in AD. f. No cases had significant pPERK staining in the cerebellum.

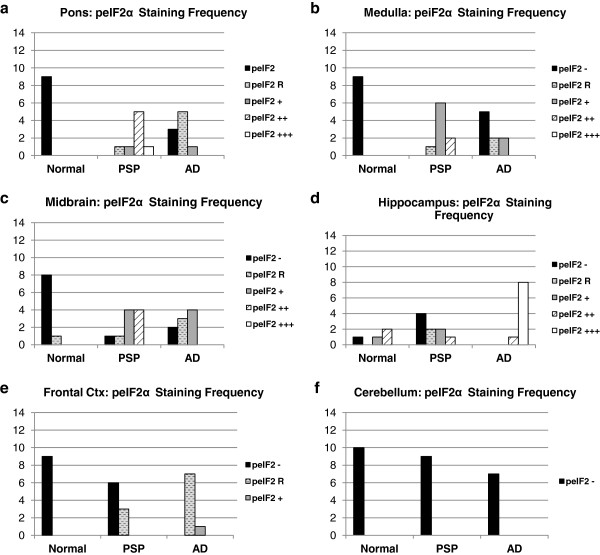

Figure 4.

Frequency of peIF2α staining scores in PSP, AD, and normal brain. Distribution of peIF2α staining scores. +++ = widespread activation, ++ = moderate activation, + = diffuse activation, R = rare activation, - = no activation. Y-axis indicates number of cases with a particular peIF2α staining score. All P-values obtained using Fisher exact test. a-c. PSP cases had the strongest peIF2α staining in the pons (PSP vs. Normal: p = 4.1E-5) and the medulla (PSP vs. Normal: p = 6.0E-6), as well as moderate staining in the midbrain (PSP vs. Normal: p = 0.00041) which was affected in all PSP cases. d-e. AD cases had the strongest peIF2α staining in the hippocampus (AD vs. Normal: p = 0.0042) and moderate staining in the frontal cortex (AD vs. Normal: p = 4.1E-5) both of which were affected in AD. f. No cases had significant peIF2α staining in the cerebellum.

PSP cases as a group showed significantly more pPERK and peIF2α staining in the pons, medulla, and midbrain compared to elderly controls. For pPERK, only one control subject (age 63) showed “rare” positive cells in the pons and medulla. This is not the same control subject that displayed Lewy body pathology in the medulla. In the midbrain, very few controls were positive for pPERK. For peIF2α, most controls were negative in these brain areas except for a single subject with rare positive cells in the medulla. For AD, there were more positive cases with a higher density of positive cells compared to controls but less than found in PSP (Figures 3 and 4a-c, Table 1).

Table 1.

P-values for comparison of pPERK and pEIF2α immunoreactivity in PSP, AD, and normal controls for different brain regions

| Comparison groups | |

Pons |

|

Medulla |

|

Midbrain |

|

Hippocampus |

|

Frontal cortex |

|

Cerebellum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pPERK | peIF2α | pPERK | peIF2α | pPERK | peIF2α | pPERK | peIF2α | pPERK | peIF2α | pPERK | peIF2α | |

|

AD vs. Normal |

3.4E-5 |

0.0045 |

0.034 |

0.041 |

0.0026 |

0.0037 |

0.0006 |

0.0042 |

4.1E-5 |

4.1E-5 |

0.4 |

1 |

|

PSP vs. AD |

3.8E-4 |

0.00049 |

1.7E-4 |

0.028 |

4.0E-7 |

0.009 |

0.000021 |

8.2E-5 |

1.6E-4 |

0.0049 |

0.5 |

1 |

| PSP vs. Normal | 3.8E-9 | 4.1E-5 | 6.1E-7 | 6.0E-6 | 6.0E-6 | 1.4E-4 | 0.0034 | 0.073 | 0.0045 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 |

P-values are from a Fisher exact test. “E” indicates “x 10^”. pPERK and peIF2α staining in PSP brainstem areas (pons, medulla, midbrain) were significantly greater than in AD or normal brainstem areas. AD brainstem areas had significantly more pPERK and peIF2α staining than normal brainstem areas. In contrast, primary AD-affected brain areas (hippocampus, frontal cortex) had significantly more pPERK and peIF2α staining than PSP or normal hippocampus and frontal cortex. There was no difference in staining between AD, PSP, or normal brains in the cerebellum.

In the hippocampus and frontal cortex, AD cases as a group scored significantly higher than PSP or normal elderly controls for both pPERK and peIF2α staining (Table 1). pPERK and peIF2α staining was especially strong in the AD hippocampus, with nearly all cases demonstrating high levels of positive cells. All PSP cases had mild to moderate pPERK staining in the hippocampus, though not all cases demonstrated peIF2α staining. Surprisingly, many normal elderly controls demonstrated at least a mild level of pPERK and peIF2α positive cells in the hippocampus (Figures 1c, 2c, 3d, and 4d). Staining was generally milder in the frontal cortex than in the hippocampus, although AD cases still scored significantly higher than PSP cases or normal controls (Figures 3e and 4e). PSP cases scored significantly higher than normal controls for pPERK staining but not for peIF2α staining (Table 1). Notably, the pons, medulla, and midbrain are severely affected in PSP [2] but only moderately or mildly affected in AD [32]. Conversely, the hippocampus and frontal cortex are strongly affected in AD [32], but only mildly affected or unaffected in PSP. Thus, PERK activation is strongest in areas of the brain highly affected by pathology in PSP and AD. Nearly all cases were negative for pPERK and peIF2α in the folia of the cerebellum (Figures 1d, 2d, 3f, and 4f), although one AD case showed rare staining in this area, but, in general, there is little to no pathology in this area in PSP or AD, and thus our findings are consistent with the inference that pathology and PERK activation occur in the same disease-affected brain areas.

Activation of pPERK in htau positive cells

We were interested in whether the UPR is activated in cells affected by tau pathology. We performed double immunofluorescence staining for pPERK and htau on sections of pons and hippocampus in PSP, AD, and normal controls (Figure 5a). In PSP pons, an average of 72% of pPERK positive cells were also positive for htau. However, only 43% of htau positive cells were also positive for pPERK (Figure 3c). This substantial overlap is in contrast to AD hippocampus, in which only 20% of pPERK positive cells also stained for htau and only 12% of htau positive cells stained for pPERK (Figure 3d). Overlap between htau and pPERK staining was also low in PSP and normal hippocampus (data not shown). In the pons, overlap between pPERK puncta and htau occurred mostly in cells with diffuse, cytoplasmic htau staining rather than dense, fibrillar staining (Figure 3b). This suggests that PERK is activated in pre-tangle neurons. Hoozemans et al.[25] described similar distribution of htau/pPERK staining in AD hippocampus.

Figure 5.

Hyperphosphorylated tau and pPERK partially co-localize in PSP pons and AD hippocampus. a. Example of a neuron co-stained for htau (red) and pPERK (green). Tau staining is widespread and diffuse. pPERK staining is punctate and localized to the soma and proximal neurites. b. pPERK staining occurred mostly in cells with diffuse, non-fibrillar htau staining. Cells with dense, fibrillar htau staining did not stain for activated PERK (*). c. In PSP pons, most pPERK positive cells also stained for htau (72%), whereas fewer than half of htau stained cells (43%) also stained positive for pPERK. d. htau and pPERK staining overlapped very little in AD hippocampus (14% and 20%). Scale bars are 50 μm unless otherwise indicated.

PERK is activated in normal hippocampus

Une xpectedly, we found pPERK and peIF2α staining in the hippocampus of age-matched elderly normal controls as described above. To follow up on this finding, we expanded our initial control hippocampus sample to include cases with a wide range of ages (range: 16–92, mean: 52.4; see Additional file 1: Table S1). We found that age significantly correlated with the pPERK staining score (Figure 6a). The older the subject, the more likely they were to have high levels of PERK activation in the hippocampus. However, not all aged normal controls demonstrated hippocampal pPERK activation although some subjects at all ages examined here were negative for pPERK staining.

Figure 6.

Severity of PERK activation in normal hippocampus correlates with age and tau pathology. a. Plot of pPERK staining score (X-axis) versus subject age at death (Y-axis). Each diamond represents one normal subject. Some individuals both young and old were negative for pPERK staining. Of those that stained positive for pPERK (including those showing rare through +++ levels of immunoreactivity), older individuals tended to have more severe pPERK staining scores. b. Frequency table plotting htau score against pPERK staining score in normal hippocampus. Htau score and pPERK score were positively correlated (Spearman R: .7523; p = 0.0002). The higher the htau score of an individual hippocampus, the higher the pPERK staining score tended to be. Htau scores were obtained from the CNDR Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Database [33] using antibody PHF-1.

We also found that the level of tau pathology correlated with pPERK staining. The more tau pathology (as measured by PHF-1 staining) in a normal hippocampus, the more likely that the hippocampus was also positive for activated PERK (Figure 6b). All controls negative for pPERK staining were also negative for htau staining; cases with severe pPERK staining scores also scored high for htau. This correlation was significant (Spearman R: 0.7523, p = .0002). There was no correlation between pPERK staining in the hippocampus and Aβ amyloid plaque pathology (as measured by Thioflavin S staining to detect senile plaques); all normals with high pPERK scores and relatively high tau scores in the hippocampus were negative for Aβ amyloid plaques and Lewy bodies (data not shown).

PERK protein coding variants are associated with PSP risk

Alleles at rs7571971 are significantly associated with PSP risk [10]. To identify other SNPs in high linkage disequilibrium with rs7571971, we evaluated 1000 Genomes data for subjects of European ancestry. As assessed by LD measure r2[34], 14 SNPs were in high LD with rs7571971 (r2 > 0.8), including the 3 non-synonymous coding variants. Of these 14, none fell in the coding region of any gene besides EIF2AK3 and all but 5 fell within EIF2AK3 (Table 2).

Table 2.

SNPs in high LD with rs7571971

| SNP | Gene | Distance in base pairs from GWAS hit SNP | RSquared | DPrime | Coordinate_HG18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1805165 |

EIF2AK3 |

20460 |

0.889 |

1 |

88656006 |

| rs6739095 |

EIF2AK3 |

15287 |

0.886 |

0.96 |

88661179 |

| rs11898161 |

EIF2AK3 |

13703 |

0.925 |

1 |

88662763 |

| rs1913671 |

EIF2AK3 |

4532 |

0.886 |

0.96 |

88680998 |

| rs11681299 |

EIF2AK3 |

6381 |

0.889 |

1 |

88682847 |

| rs867529 |

EIF2AK3 |

17922 |

0.889 |

1 |

88694388 |

| rs6731022 |

EIF2AK3 |

21684 |

0.886 |

0.96 |

88698150 |

| rs11684404 |

EIF2AK3 |

29271 |

0.886 |

0.96 |

88705737 |

| rs11680549 |

EIF2AK3 |

30997 |

0.813 |

0.957 |

88707463 |

| rs6547787 |

|

34385 |

0.886 |

0.96 |

88710851 |

| rs1606803 |

|

37965 |

0.889 |

1 |

88714431 |

| rs62157778 |

|

38739 |

0.889 |

1 |

88715205 |

| rs13003510 |

|

46139 |

0.925 |

1 |

88722605 |

| rs13001657 | 51260 | 0.888 | 0.96 | 88727726 |

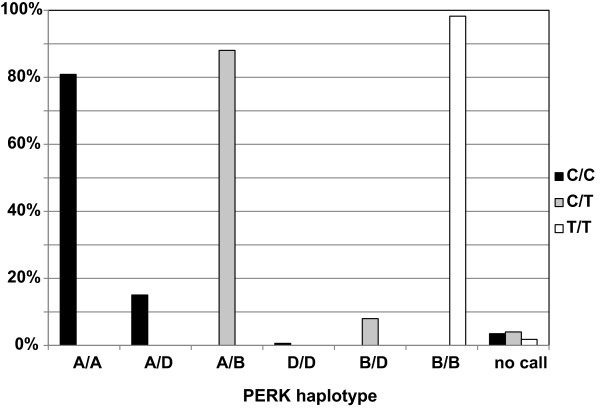

The 3 non-synonymous coding variants in EIF2AK3 were Ser136Cys, Arg166Gln, and Ser704Ala. When haplotypes were constructed from 1000 Genome data, there were two common haplotypes (Table 3): Ser-Arg-Ser (haplotype A) and Cys-Gln-Ala (haplotype B) with predicted frequencies of 0.64 and 0.29, respectively; one uncommon haplotype, Ser-Gln-Ser (haplotype D), with a frequency of 0.06; and 4 rare haplotypes of frequency close to 1/1000. The top PSP GWAS SNP for this gene is rs7571971, a 2-allele polymorphism in EIF2AK3 intron 2 with a minor allele frequency of 0.25-0.28 [10]. From the 1000 genome analysis, the minor allele for rs7571971 is almost perfectly correlated with haplotype B and the major allele with haplotypes A and D.

Table 3.

PERK haplotypes

| rs867529-rs13045-rs1805165 | Affected amino acids |

Alleles (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP (n = 994) | ||||

|

Haplotype A |

GCA |

Ser136-Arg166-Ser704 |

1233 |

(62.5) |

|

Haplotype B |

CTC |

Cys136-Gln166-Ala704 |

626 |

(31.7) |

| Haplotype D | GTA | Ser136-Gln166-Ser704 | 113 | (5.7) |

To confirm the relationship of LD amongst SNP alleles in PSP subjects, we genotyped 1,043 PSP cases for rs7571971, and the 3 coding variant SNPs. The genotypes for these four SNPs were then phased using maximum likelihood. We observed that, in PSP cases, haplotype frequencies were almost identical to those from 1000 Genomes data: for A, 0.645 versus 0.642; for B, 0.288 versus 0.301; and for D, 0.061 versus 0.053. Again haplotypes A and D are completely correlated with rs7571971 allele C (Figure 7), the protective PSP allele. Haplotype B is completely correlated with allele T, the high risk PSP allele. Recently Liu et al.[31] showed that when lymphoblastoid cell lines are treated with thapsigarin to induce ER stress, cells homozygous for the B haplotype showed stronger activation than cells homozygous for the A haplotype. Thus B is the high-risk haplotype for PSP suggesting that activation is not a protective response, but rather increases risk for PSP.

Figure 7.

Comparison of PERK haplotype with GWAS risk allele. A GWAS for PSP identified a risk locus on chromosome 2 (rs7571971). The common, low risk allele at this locus is cytosine (C) and the PSP risk allele is thymine (T) [10]. Among individuals homozygous for C at this locus, all harbor PERK haplotype A or D in some combination. Individuals heterozygous (C/T) at this locus were heterozygous for haplotypes A, B, and/or D. Individuals homozygous for T at the GWAS risk locus were always homozygous for PERK haplotype B. This demonstrates that one of the two amino acid changes conferred by the B PERK haplotype that are not shared by the D haplotype may be responsible for the PSP risk evident on Chr. 2.

Discussion

We found that PERK is activated in disease-affected brain regions in PSP, including the pons, medulla, and midbrain. We also found that PERK’s downstream effector, eIF2α, is activated similarly in PSP brainstem areas. In contrast, PERK and eIF2 are not activated or only weakly activated in normal and AD brainstem, respectively. We confirmed that AD cases have strong immunoreactivity for pPERK and peIF2α in the pyramidal cells of the hippocampus [25] and in the frontal cortex. In contrast, PSP cases show mild to moderate pPERK staining in these regions [26]. PERK and eIF2α were not activated in the cerebellum in either disease. In AD and PSP, the pattern of UPR activation pllels the regional distribution of pathology in these two disorders.

We explored the relationship between abnormal tau deposits and UPR activation in the PSP brainstem. Although there is some overlap between cells with activated PERK and cells with htau, at least half of htau-positive cells do not have concurrent PERK activation. A greater proportion of pPERK positive cells were also positive for tau, but 25% stained for pPERK alone. Thus, although PERK is activated in brain regions highly affected by tau pathology, htau and pPERK do not necessarily overlap at the single cell level. One potential explanation for lack of complete overlap may be that PERK activation precedes tangle formation, and is no longer activated in cells with mature tangles. We found that overlap between pPERK and htau mostly occurred in cells with diffuse htau staining rather than dense tau staining, supporting this hypothesis. Similarly, Hoozemans et al. (2009) found that cells in the AD hippocampus that were positive for pPERK also stained for markers of early tau aggregation [25]. This evidence suggests that PERK activation may temporally precede overt tau aggregation, and could be triggered by immunohistochemically undetectable levels of abnormal tau. The genetic data implicating both PERK and tau in PSP supports a plausible temporal relationship between PERK activation and tau aggregation.

Genetic findings [10] and the data presented here implicate PERK as well as the UPR in the pathogenesis of PSP. Genetic findings also associate MAPT with PSP [7,10,35,36], and along with the presence of aggregated tau as the key neuropathologic feature of PSP, these data clearly establish that tau is intimately linked to PSP pathogenesis. While the UPR is activated by misfolded proteins within the ER, and aggregated misfolded tau occurs in PSP, AD, and other tauopathies, tau is a cytosolic protein and does not appear to traffic through the ER as part of a secretory pathway. In normal neurons, most tau protein is intracellular and attached to microtubules. In tauopathies, tau aggregates in the cytoplasm of cells, in cellular processes, and at nerve terminals, but there is no evidence that tau aggregates in the ER. Recent work in mouse models of α-synucleinopathies [37,38] and studies on PD autopsy material [38] suggest that small amounts of α-synuclein can be found in ER, and that in the disease state, these levels are elevated, thereby activating the ER stress response. Still, since there is no direct evidence that tau traffics through the ER, or evidence of tau aggregates in the ER, it is unlikely that misfolded tau directly activates the canonical UPR. This view is supported by the fact that in PSP, pPERK and pEIF2α are activated in cells with no observable tau pathology, but we cannot exclude the possibility that very low or undetectable levels of aggregated tau are present. Rather, a more likely explanation is that tau-induced cytoplasmic events act to trigger the UPR by an unknown mechanism, which in turn influences the degradation of tau. A possible mechanism is that cytoplasmic aggregated tau may inhibit processes such as the ERAD-proteosome pathway used by cells to degrade misfolded ER proteins, and thus preventing the normal degradation of these proteins, stimulating ER stress [39].

PERK and eIF2α are also activated in pathology-associated regions of a number of other neurodegenerative diseases, including another tauopathy, AD [25]. The UPR is also activated in non-tau diseases that include ALS where UPR activation is observed in the spinal cord in sporadic cases [28], and in PD where UPR activation occurs in the substantia nigra [27]. Expanded-repeat huntingtin, the pathological protein in Huntington’s disease, induces ER stress in culture [40]. Notably, these diseases share a common pathology, i.e. the accumulation of abnormal aggregated proteins in the CNS. Thus, there may be a common mechanism by which aggregated cytoplasmic proteins activate the UPR. The genetic association between PERK and PSP suggests that this UPR activation can influence the disease process, at least in the case of PSP.

Surprisingly, we found that 10/14 normal controls over 50 years of age had at least minimal activation of pPERK in the hippocampus. This is in contrast to previous studies that report no pPERK staining in this region in normal controls [26]. In these subjects, the degree of pPERK immunoreactivity correlated positively with both the degree of htau immunoreactivity and age, but did not correlate with amyloid pathology. The presence of at least some tau pathology in the hippocampus of normal subjects is consistent with work by others [41], and could potentially indicate either pre-clinical AD or early neurofibrillary tangle predominant dementia (NFTD). However, in the absence of clinical symptoms, it is not possible to make either diagnosis. These findings in normal controls are consistent with the idea that the activation of the UPR is due to the tau pathology and not the amyloid pathology.

We reported strong genetic evidence that EIF2AK3 genotypes confer risk for PSP [10]. The strongest signal comes from single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7571971 that is within EIF2AK3. There are several non-synonymous coding polymorphisms in EIF2AK3 that track with risk and EIF2AK3 appears to be the gene in this region involved in PSP. However, another less likely but still plausible explanation is that PSP risk in this region comes from a regulatory element that is intronic, within EIF2AK3, or in a close by intergenic region and that this element controls expression of another gene. Also, the true PSP association could be from nearby genes (e.g. FOXI3 or RPIA) though this is less likely since the signal from SNPs in highlighting these genes are not as significant as SNPs within EIF2AK3. The work presented here clearly demonstrates that in PSP, PERK is activated in a region-specific pattern that matches regions where neurodegeneration occurs. Thus this functional evidence along with the strength of the genetic evidence indicates that EIF2AK3 and not an adjacent locus is the gene that confers risk for PSP.

The SNP giving the strongest EIF2AK3 signal in the PSP GWAS (rs7571971) is intragenic in intron 2. This SNP is in strong disequilibrium with 3 EIF2AK3 exonic SNPs which are non-synonymous. This relationship was predicted using 1,000 Genomes data and confirmed here in PSP subjects (Figure 7). These coding variants form two common (A and B) and one rare haplotype (D). In PSP subjects, the low risk allele [C] at rs7571971 completely correlates with haplotypes A and D while the high risk rs7571971 allele [T] completely correlates with haplotype B (Figure 7).

Work in lymphoblastoid cell lines [31] with different haplotypes show that expression of EIF2AK3 is not altered by these haplotypes. However, when the PERK arm of the UPR is activated by thapsigargin, PERK from haplotype B homozygote cells is more active in phosphorylating eIF2α when compared to PERK from cells homozygous for haplotype A. The haplotype that confers high risk for PSP produces the more active form of PERK, suggesting that activation of the UPR is pathogenic in PSP and not a protective response. This is consistent with observations in prion protein induced neurodegeneration. Moreno et al., showed that during prion replication, synaptic failure and neuronal loss is temporally associated with UPR activation and inhibition of translation. When translation is restored using over-expression of GADD34 to dephosphorylate eIF2α, survival of infected animals is prolonged. In contrast, when the UPR is activated using salubrinal, survival is decreased [42]. Both observations are consistent with activation of the PERK/eIF2α arm of the UPR enhancing neurodegeneration, as proposed here for PSP.

The two low risk haplotypes (haplotype A, Ser-Arg-Ser; and haplotype B, Ser-Gln-Ser) differ only at the middle amino acid, 166— this amino acid is unlikely to functionally influence PERK activation. The low and high risk (Haplotype B, Cys-Gln-Cys) haplotypes differ at both positions 166 and 704, and one or both may influence PERK activity. Amino acid 166 is on the portion of PERK that is in the ER lumen and positioned where this protein senses mis-folded proteins. Position 704 is on the cytoplasmic side of PERK, a segment of the protein that is phosphorylated when activated and that has the active site for phosphorylating eIF2α. Additional work is needed to confirm that haplotype B PERK is the more active protein and to determine if mis-folded protein sensing or activation via auto phosphorylation is affected.

Conclusions

The PERK protein and its downstream effector eIF2α are phosphorylated in disease-affected regions in both PSP and Alzheimer’s disease. A previous study using PSP samples described UPR activation primarily in the hippocampus, a brain region not affected in this disease [26]. In contrast, we examined a large panel of brain areas (pons, medulla, midbrain, hippocampus, frontal cortex, and folia of the cerebellum) from PSP and AD cases as well as normal controls to show that this activation is disease-specific in its geographic distribution in the brain. In contrast to previous reports, we also found UPR activation in the hippocampus of a subset of our normal controls, a completely novel finding. This activation positively and significantly correlated with both age and amount of tau pathology. This suggests that tau and UPR activation are linked. We also demonstrated a genetic association between an EIF2AK3 protein coding haplotype and PSP, indicating that variation in the PERK protein affects PSP risk.

Methods

Human tissue

We obtained postmortem human pons, medulla, midbrain, frontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum samples from the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR; University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA) using the CNDR Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Database [33] and from the Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Brain Bank (MADRC; University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). We chose PSP and AD cases for lack of co-morbid diagnoses and availability of fixed tissue-- PSP and AD cases with a secondary neuropathological diagnosis (NPDx; for instance, PD) were excluded from the present study. All PSP and AD cases were evaluated by a neurologist pre-mortem and referred to the CNDR or MADRC brain donation programs, where a neuropathologist made a NPDx according to established criteria [43,44]. Controls had no clinical history or postmortem diagnosis of a neurodegenerative disease. One control displayed a moderate amount of Lewy body pathology in the medulla and another displayed a mild amount of tau deposition in the midbrain (though not in the substantia nigra). All control cases were free of Lewy bodies in the hippocampus. We age-matched all cases and controls (See Table 4 and Additional file 1: Table S1 for demographic information). Tissue used for immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence studies was fixed in either ethanol (70%) or 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight and then processed for pffin embedding and 6 μm thick sections were generated as described [45] using a Leitz 1512 microtome. The average age of PSP, AD, and normal controls was approximately 75 years. Average disease duration for PSP patients was 6.7 years, while the average duration for AD patients was 10.8 years. The average post-mortem interval (PMI) for all cases was 10.2 hours (Table 4, and Additional file 1: Table S1). Pontine sections included the locus coeruleus and surrounding tegmentum, midbrain sections included the substantia nigra, medulla sections included the olivary nucleus, hippocampal sections included the CA and dentate regions, frontal cortex sections included both white and gray matter, and cerebellar sections included the folia.

Table 4.

Subject information

| n | Avg age of onset | Avg age at death | Avg disease duration | % female | Avg PMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal – age-matched |

15 |

N/A |

71.7(8.4) |

N/A |

46.7 |

12.7(8.5) |

|

Normal – non age-matched |

12 |

N/A |

54.5(24.9) |

N/A |

66.7 |

9.1(3.4) |

|

Normal - total |

27 |

N/A |

64.0(19.4) |

N/A |

56.7 |

11.1(6.9) |

|

PSP |

17 |

66.8(5.8) |

73.7(5.2) |

6. 7(2.2) |

64.7 |

11.7(6.0) |

| AD | 9 | 65.0(6.3) | 75.8(5.1) | 10. 8(3.4) | 44.4 | 9.4(5.8) |

There were no significant differences between groups for average age at death (ANOVA, p = 0.33), post-mortem interval (ANOVA, p = 0.54), average age of onset (PSP and AD only, Student’s t-test, p = .45) or percent female (Chi Square, p = 0.89). Average disease duration for AD was significantly longer than for PSP (Student’s t-test, p = 0.002). Standard deviations indicated inside parenthesis.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described [46,47]. We depffinized brain sections on slides using xylene (Mallinckrodt Baker Inc., Phillipsburg, NJ), and then hydrated them through a series of ethanol washes, and quenched endogenous peroxidases by immersing sections in a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and methanol. Following a wash in running water, we performed antigen retrieval by microwaving sections immersed in citrate buffer (Thermo Shandon Limited, Astmoor, WA). We then washed sections in 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6; Fisher Scientific), blocked in 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6)/2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and applied primary antibody (incubated overnight at 4°). This wash/block procedure was identical for secondary antibody application, with an incubation time of one hr. Following another wash, we applied avidin/biotin complex (Vector Labs) to each section and incubated the sections for one hr. Finally, we developed sections with DAB chromagen (Biogenex), counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through a series of ethanol and xylene washes. Cover slips were sealed with Cytoseal (Richard Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Antibodies used are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Anitbodies used

| Antigen | Epitope | Source | Dilution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary |

pPERK |

pThr981 |

Santa Cruz |

1:4000 |

| peIF2α |

pSer51 |

Sigma-Aldrich |

1:2000 |

|

| AT8 |

pSer202/pThr205 |

Thermo Scientific |

1:7500 |

|

| Secondary | goat α rabbit IgG |

biotin |

Vector Labs |

1:1000 |

| goat α rabbit IgG |

AlexaFluor 488 |

Alexa |

1:500 |

|

| goat α mouse IgG | AlexaFluor 594 | Alexa | 1:500 |

Immunofluorescence (IF)

We depffinized, hydrated, quenched, and performed antigen retrieval on slide-mounted sections as described above. We then blocked sections in 0.1 M Tris/2% FBS, and applied mouse and rabbit primary antibodies (diluted in 0.1 M Tris/2% FBS). Primary antibody incubation time was 2 hr at room temperature. Following a wash in 0.1 M Tris and transfer to a “dark” chamber, we applied secondary antibodies (goat-anti-mouse and goat-anti-rabbit; Vector Labs) and let sections incubate for another two hr at room temperature. We then washed the sections again and applied 0.3% Sudan Black in 70% ethanol [48] for five min to quench endogenous lipofuscin related fluorophores. After another wash, the sections were coverslipped using Vectashield (with DAPI; Vector Labs; [49]).

Slide scoring and analysis

pPERK and peIF2 antibodies both stained cells in a characteristic punctate pattern (Figures 1a and 2a; [25,27]). We scored each tissue section for pPERK or peIF2α IHC staining according to the following scale: negative (−): no cells stained, rare (R): 1–3 cells stained, +: 4–20 cells stained, ++: 20+ cells stained, could have diffuse distribution of stained cells, may have high density of stained cells in some fields of the section, +++: high density of stained cells in almost every field of the section. A second rater confirmed scores in 20% of randomly selected slides (see Online Resource Figure 1). For double IF of hyperphosphorylated tau (htau) and pPERK, we visualized and photographed 10 fields per section and manually counted the number of htau positive cells, the number of pPERK positive cells, and the number of cells positive for both pPERK and htau. We scored all sections blind to disease group on an Olympus CHBS microscope (IHC) or an Olympus BX60 Transmitted-Reflected Light Microscope with BF/DF/DIC/Polarized Light and a SPOT RT Color digital microscope camera (IF).

Statistical analysis

We used Spearman correlations to examine correlations between level of tau pathology vs. pPERK staining and age vs. pPERK staining, Fisher’s exact test to examine association between disease condition and pPERK/peIF2α staining, Chi Square to examine sex distribution among disease/normal groups, ANOVA to examine the mean difference among disease/normal groups for average age at death and post-mortem interval, and a Student’s t-test to examine the mean difference between disease groups for average age of onset. All statistical analyses were two-sided. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level unless otherwise indicated.

Analysis of linkage disequilibrium around rs7571971

In a recent GWAS for PSP risk loci [10], a significant association was established between PSP risk and rs7571971. This SNP falls in an intron of EIF2AK3, the gene encoding PERK. While it is reasonable to assume the SNP somehow affects risk for PSP by affecting expression of EIF2AK3, it remains to be proven. To garner genetic evidence for this hypothesis, we first evaluated the pattern LD in sequence data from the 1000 Genomes project [50] and pairwise LD evaluated using SNAP (Suite of Nucleotide Analysis Programs, [51]). Based on these results, we genotyped 1043 PSP patients using TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for the following four SNPs: rs7571971, rs867529 (S136C), rs1805165 (S704A), and rs13045 (R166Q). All cases were autopsied and had a neuropathologic diagnosis of PSP [52]. Genotyping was done according to manufacturer’s protocol. PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 minutes, then 50 cycles of 92°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute, 4°C for 2 minutes. Genotypes were visualized and called using a 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System and the allelic discrimination function of Sequence Detection System V.2.4 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Finally, we phased the resulting four-SNP genotypes using eHap software [53], which provides maximum likelihood estimates of haplotype frequencies. Approval for the use of de-identified patient samples was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB); sample and demographic information collection at each participating site was approved by institution-specific IRB. Informed consent was obtained for all samples collected in a clinical setting.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LS carried out the immunostaining experiments and scoring, performed the Taqman genotyping, participated in the genotyping analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SX performed statistical analysis of immunostaining experiments. AN performed statistical analysis on genotyping data. RA and SG characterized, prepared and contributed a subset of tissue samples from patients with PSP. PSP-GSG characterized, prepared and contributed genetic samples from patients with PSP. VMYL and JQT contributed to study design and characterized, prepared and contributed tissue samples from PSP, AD and normal controls. BD performed linkage disequilibrium analysis and participated in drafting the manuscript. GDS conceived of the study, contributed to study design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Scoring system examples. Representative fields from brain areas that scored “-“ (negative), “R” (rare), “+” (mild staining), “++” (moderate staining), and “+++” (heavy staining), along with scoring criteria. Table S1. Individual Case Information.

Contributor Information

Lauren D Stutzbach, Email: lstutz@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Sharon X Xie, Email: sxie@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Adam C Naj, Email: adamnaj@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Roger Albin, Email: ralbin@med.umich.edu.

Sid Gilman, Email: sgilman80@gmail.com.

Virginia M Y Lee, Email: vmylee@upenn.edu.

John Q Trojanowski, Email: trojanow@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Bernie Devlin, Email: devlinbj@upmc.edu.

Gerard D Schellenberg, Email: gerardsc@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIA Pre-Doctoral Fellowship 1F31AG043254 – 01, NIH/NIA grant R37 AG11762 (GDS), AG10124 and AG017586 as well as a grant from the Rainwater and Wyncote foundations, and from Cure PSP Society. Additional support came from NIH/NINDS (U24 NS072026), the NIH/NIA (P30 AG19610), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05–901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Many thanks to Michele Hawk, M.S., D.V.M. for her technical contributions to this work. Special thanks to the staff of the CNDR Brain Bank: Theresa Schuck (manager), John Robinson, and Kevin Raible for their technical expertise and support and for supplying patient samples. Thanks also to the staff at the University of Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center for providing patient samples and information. Finally, many thanks to Sherry Beecher, Laura Cantwell, Beth Dombroski, Ph.D., Reteeka Sud, Ph.D., Evan Geller, and Lindsay Barbuto, as well as students Michael Wong and Luckmini Liyanage.

PSP Genetics Study Group information

Günter U. Höglinger49, Ulrich Müller50, Dennis W. Dickson8, Rosa Rademakers8, Rohan de Silva9, Irene Litvan10, Rachel G Gross29, John Hardy9, Peter Heutink42, Howard I Hurtig29, Matthew J Farrer43, Ryan J Uitti12, Jana Vandrovcova9, John C. van Swieten11, Zbignew K. Wszolek12, Eduardo Tolosa13, Pau Pastor14-16, Tamas Revesz17, Andrew J. Lees9,17, Elena Alonso14,15, Manuela Apfelbacher18, Steven E. Arnold44, Jesus Avila19, Thomas G. Beach20, Agnita J.W. Boon11, Wang Zheng Chiu11, Laura Donker Kaat11, Peter P. De Deyn45, Ranjan Duara46, Sebastiaan Engelborghs45, Yvette Bordelon21, Justo García de Yebenes22, NiCole A. Finch8, Owen A. Ross8, Robyn Flook23, Matthew P. Frosch24, Carles Gaig13, Douglas R. Galasko25, Eliezer Masliah25,26, Marla Gearing27, Bernadino Ghetti28, Salvatore Spina28, Neill R. Graff-Radford12, Murray Grossman29, Jorge L. Juncos30, Hans A. Kretzschmar31, Andrew P. Leiberman32, Kelly E Lyons47, Luke A. Massey9, Sean S. O’Sullivan9, Rajesh Pahwa47, Laura Silveira-Moriyama9, Catriona A. McLean33, Alberto Rabano34, Alex Rajput35, Sigrun Roeber31, Jonathan D. Rohrer36, Martin N. Rossor36, Wallace W Tourtellotte48, Claire Troakes37, Safa Al-Sarraj37, Juan C. Troncoso38, Vivianna M. Van Deerlin1,2, Jean Paul G. Vonsattel39, Charles L. White40 and Chris Zarrow41.

8Department of Neuroscience, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, USA. 9Reta Lila Weston Institute, University College London (UCL) Institute of Neurology, London, UK. 10Department of Neurology, Division of Movement Disorders, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, USA. 11Department of Neurology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 12Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, USA. 13Neurology Service, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Hospital Clínic, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. 14CIBERNED, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. 15Neurogenetics laboratory, Division of Neurosciences, University of Navarra Center for Applied Medical Research, Pamplona, Spain. 16Department of Neurology, University of Navarra, Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain. 17Department of Molecular Neuroscience, Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders, UCL Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, UK. 18Institute of Legal Medicine, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany. 19Centro de Biologia Molecular Severo Ochoa (CSIC-UAM), Campus Cantoblanco, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. 20Civin Laboratory for Neuropathology, Banner Sun Health Research Institute, Sun City, Arizona, USA. 21Department of Neurology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA. 22Department of Neurology, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain. 23Centre for Neuroscience, Flinders University and Australian Brain Bank Network, Victoria, Australia. 24C.S. Kubik Laboratory for Neuropathology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 25Department of Neurosciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 26Department of Pathology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 27Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 28Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. 29Department of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 30Department of Neurology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 31Institut für Neuropathologie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and Brain Net Germany, Munich, Germany. 32Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. 33Victorian Brain Bank Network, Mental Health Research Institute, Victoria, Australia. 34Department of Neuropathology and Tissue Bank, Fundación Centro Investigación Enfermedades Neurológicas (CIEN), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. 35Division of Neurology, Royal University Hospital, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan, Canada. 36Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, Dementia Research Centre, UCL Institute of Neurology, UCL, London, UK. 37MRC London Neurodegenerative Diseases Brain Bank, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, UK. 38Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. 39Department of Pathology and the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA. 40Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA. 41Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, University of Southern California, Downey, California, USA. 42Department of Clinical Genetics, Vrije Universiteit (VU) Medical Center, Section Medical Genomics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 43Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. 44Department of Psychiatry, Center for Neurobiology and Behavior, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 45Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium. 46Wien Center for Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders, Mt. Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, Florida, USA. 47Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas, USA. 48Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center, Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles Healthcare Center, Los Angeles, California, USA. 49Department of Neurology, Philipps-Universität, Marburg, Germany. 50Institut for Humangenetik, Justus-Liebig-Universität, Giessen, Germany.

References

- Litvan I, Agid Y, Calne D, Campbell G, Dubois B, Duvoisin RC, Goetz CG, Golbe LI, Grafman J, Growdon JH. et al. Clinical research criteria for the diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome): report of the NINDS-SPSP international workshop. Neurology. 1996;1:1–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.47.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele JC, Richardson JC, Olszewski J. Progressive supranuclear palsy. A heterogeneous degeneration involving the brain stem, basal ganglia and cerebellum with vertical gaze and pseudobulbar palsy, nuchal dystonia and dementia. Arch Neurol. 1964;1:333–359. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1964.00460160003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Rademakers R, Hutton ML. Progressive supranuclear palsy: pathology and genetics. Brain Pathol. 2007;1:74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore C, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;1:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford PM, Halliday GM, Brooks WS, Kwok JB, Storey CE, Creasey H, Morris JG, Fulham MJ, Schofield PR. Progressive supranuclear palsy pathology caused by a novel silent mutation in exon 10 of the tau gene: expansion of the disease phenotype caused by tau gene mutations. Brain. 2000;1:t 5:880–893. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor P, Pastor E, Carnero C, Vela R, Garcia T, Amer G, Tolosa E, Oliva R. Familial atypical progressive supranuclear palsy associated with homozigosity for the delN296 mutation in the tau gene. Ann Neurol. 2001;1:263–267. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(20010201)49:2<263::AID-ANA50>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorkaj P, Muma NA, Zhukareva V, Cochran EJ, Shannon KM, Hurtig H, Koller WC, Bird TD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Schellenberg GD. An R5L tau mutation in a subject with a progressive supranuclear palsy phenotype. Ann Neurol. 2002;1:511–516. doi: 10.1002/ana.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi G, Gasparoli E, Pasquali C, Di Fede G, Testa D, Albanese A, Bracco F, Tagliavini F. Progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson’s disease in a family with a new mutation in the tau gene. Ann Neurol. 2004;1:448. doi: 10.1002/ana.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros R, Thobois S, Streichenberger N, Kopp N, Sánchez MP, Pérez M, Hoenicka J, Avila J, Honnorat J, de Yébenes JG. A new mutation of the tau gene, G303V, in early-onset familial progressive supranuclear palsy. Arch Neurol. 2005;1:1444–1450. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.9.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglinger GU, Melhem NM, Dickson DW, Sleiman PM, Wang LS, Klei L, Rademakers R, de Silva R, Litvan I, Riley DE. et al. Identification of common variants influencing risk of the tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat Genet. 2011;1:699–705. doi: 10.1038/ng.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Litvan I, Houlden H, Adamson J, Dickson D, Perez-Tur J, Hardy J, Lynch T, Bigio E, Hutton M. Association of an extended haplotype in the tau gene with progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;1:711–715. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad C, Andreadis A, Trojanowski JQ, Dickson DW, Kang D, Chen X, Wiederholt W, Hansen L, Masliah E, Thal LJ. et al. Genetic evidence for the involvement of tau in progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann Neurol. 1997;1:277–281. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C, Vidal-Taboada JM, Ezquerra M, Lorenzo E, Martinez-Lage P, Blazquez M, Tolosa E, Pastor P. 5′-Upstream variants of CRHR1 and MAPT genes associated with age at onset in progressive supranuclear palsy and cortical basal degeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;1:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;1:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;1:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper W, Hoozemans JJM. Endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control in neurodegenerative disease: the good, the bad and the therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2009;1:615–626. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozutsumi Y, Segal M, Normington K, Gething M, Sambrook J. The presence of malfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum signals the induction of glucose-regulated proteins. Nature. 1988;1:462–464. doi: 10.1038/332462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus S, Glimcher LH, Hetz C. Protein folding stress in neurodegenerative diseases: a glimpse into the ER. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011. pp. 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;1:249–258. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijholt DAT, de Graaf TR, van Haastert ES, Oliveira aO, Berkers CR, Zwart R, Ovaa H, Baas F, Hoozemans JJM, Scheper W. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates autophagy but not the proteasome in neuronal cells: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Differ. 2011;1:1071–1081. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski DT, Arnold SM, Miller CN, Wu J, Li J, Gunnison KM, Mori K, Sadighi Akha A, Raden D, Kaufman RJ. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;1:e374–e374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R. et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. 2003;1:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;1:e423–e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouschop KMA, van den Beucken T, Dubois L, Niessen H, Bussink J, Savelkouls K, Keulers T, Mujcic H, Landuyt W, Voncken JW. et al. The unfolded protein response protects human tumor cells during hypoxia through regulation of the autophagy genes MAP1LC3B and ATG5. J Clin Invest. 2010;1:127–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI40027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJM, van Haastert ES, Nijholt DT, Rozemuller AJM, Eikelenboom P, Scheper W. The unfolded protein response is activated in pretangle neurons in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Am J Pathol. 1251. pp. 174–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nijholt DA, van Haastert ES, Rozemuller AJ, Scheper W, Hoozemans JJ. The unfolded protein response is associated with early tau pathology in the hippocampus of tauopathies. J Pathol. 2012;1:693–702. doi: 10.1002/path.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJM, van Haastert ES, Eikelenboom P, de Vos RAI, Rozemuller JM, Scheper W. Activation of the unfolded protein response in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;1:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin JD, Farg M, Walker AK, McLean C, Tomas D, Horne MK. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of the unfolded protein response in human sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;1:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Popko B, Roos RP. The unfolded protein response in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;1:1–29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makioka K, Yamazaki T, Fujita Y, Takatama M, Nakazato Y, Okamoto K. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress defined by activated unfolded protein response in multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 2010;1:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Hoppman N, O’Connell JR, Wang H, Streeten EA, McLenithan JC, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR. A functional haplotype in EIF2AK3, an ER stress sensor, is associated with lower bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;1:331–341. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie SX, Baek Y, Grossman M, Arnold SE, Karlawish J, Siderowf A, Hurtig H, Elman L, McCluskey L, Van Deerlin V. et al. Building an integrated neurodegenerative disease database at an academic health center. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;1:e84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.08.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Risch N. A comparison of linkage disequilibrium measures for fine-scale mapping. Genomics. 1995;1:311–322. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademakers R, Melquist S, Cruts M, Theuns J, Del-Favero J, Poorkaj P, Baker M, Sleegers K, Crook R, De Pooter T. et al. High-density SNP haplotyping suggests altered regulation of tau gene expression in progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;1:3281–3292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi Y, Josephs KA, Cookson N, Dickson DW. APOE E4 is a determinant for Alzheimer type pathology in progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 2003;1:240–245. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000044340.37138.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla E, Coune P, Liu Y, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Iwatsubo T, Schneider BL, Lee MK. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is important for the manifestations of alpha-synucleinopathy in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;1:3306–3320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5367-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla E, Jensen PH, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Glabe C, Lee MK. Accumulation of toxic alpha-synuclein oligomer within endoplasmic reticulum occurs in alpha-synucleinopathy in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;1:3301–3305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5368-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abisambra JF, Jinwal UK, Blair LJ, O’Leary JC 3rd, Li Q, Brady S, Wang L, Guidi CE, Zhang B, Nordhues BA. et al. Tau Accumulation Activates the Unfolded Protein Response by Impairing Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation. J Neurosci. 2013;1:9498–9507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5397-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie P, Snapp EL. Changes in BiP availability reveal hypersensitivity to acute endoplasmic reticulum stress in cells expressing mutant huntingtin. J Cell Sci. 2011;1:3332–3343. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;1:960–969. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318232a379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JA, Radford H, Peretti D, Steinert JR, Verity N, Martin MG, Halliday M, Morgan J, Dinsdale D, Ortori CA. et al. Sustained translational repression by eIF2alpha-P mediates prion neurodegeneration. Nature. 2012;1:507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature11058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvan I, Hauw JJ, Bartko JJ, Lantos PL, Daniel SE, Horoupian DS, McKee A, Dickson D, Bancher C, Tabaton M. et al. Validity and reliability of the preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for progressive supranuclear palsy and related disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;1:97–105. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;1:S1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using pffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;1:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippa CF, Rosso AL, Stutzbach LD, Neumann M, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 burden in familial Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2009;1:1483–1488. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Lee EB, Moberg PJ, Stutzbach L, Kazi H, Han L-Y, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Olfactory epithelium amyloid-beta and paired helical filament-tau pathology in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;1:462–469. doi: 10.1002/ana.21910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romijn HJ, van Uum JF, Breedijk I, Emmering J, Radu I, Pool CW. Double immunolabeling of neuropeptides in the human hypothalamus as analyzed by confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;1:229–236. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uryu K, Giasson BI, Longhi L, Martinez D, Murray I, Conte V, Nakamura M, Saatman K, Talbot K, Horiguchi T. et al. Age-dependent synuclein pathology following traumatic brain injury in mice. Exp Neurol. 2003;1:214–224. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;1:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O’Donnell CJ, de Bakker PI. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;1:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauw JJ, Daniel SE, Dickson D, Horoupian DS, Jellinger K, Lantos PL, McKee A, Tabaton M, Litvan I. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy) Neurology. 1994;1:2015–2019. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.11.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltman H, Roeder K, Devlin B. Evolutionary-based association analysis using haplotype data. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;1:48–58. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Scoring system examples. Representative fields from brain areas that scored “-“ (negative), “R” (rare), “+” (mild staining), “++” (moderate staining), and “+++” (heavy staining), along with scoring criteria. Table S1. Individual Case Information.