Abstract

A cold sensation (hie) is common in Japanese women and is an important treatment target in Kampo medicine. Physicians diagnose patients as having hiesho (cold disorder) when hie disturbs their daily activity. However, differences between hie and hiesho in men and women are not well described. Hie can be of three types depending on body part where patients feel hie. We aimed to clarify the characteristics of patients with hie and hiesho by analyzing data from new patients seen at the Kampo Clinic at Keio University Hospital between 2008 and 2013. We collected information about patients' subjective symptoms and their severity using visual analogue scales. Of 4,016 new patients, 2,344 complained about hie and 524 of those were diagnosed with hiesho. Hie was most common in legs/feet and combined with hands or lower back, rather than the whole body. Almost 30% of patients with hie felt upper body heat symptoms like hot flushes. Cold sensation was stronger in hiesho than non-hiesho patients. Patients with hie had more complaints. Men with hiesho had the same distribution of hie and had symptoms similar to women. The results of our study may increase awareness of hiesho and help doctors treat hie and other symptoms.

1. Introduction

In Japan, hie (cold sensation) and hiesho (cold disorder) are different terms. While hie is used to describe the subjective, uncomfortable feeling of coldness, hiesho is the diagnosis given by physicians to patients with cold sensations that disturb their daily living. Therefore, the first distinction to make is one between normal and hie groups. Those who experience hie can further be subdivided into hiesho and non-hiesho categories (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hie and hiesho. In Japan hie (cold sensation) and hiesho (cold disorder) are different terms. While hie is the term used to describe the subjective, uncomfortable feeling of coldness, hiesho is the diagnosis given by physician to patients with cold sensation disturbing their daily living. Therefore, the first distinction is between normal and hie group. The hie group is subdivided into hiesho and non-hiesho.

Hiesho is the most common diagnosis given in Japanese Kampo clinics [1]. In Japanese Kampo medicine, hiesho is treated as a unique pathological condition. In contrast, cold sensation is only one of many symptoms asked about in a review of systems in Western medicine. One definition of hiesho for diagnosis is an “abnormal, subjective sensitivity to coldness in the lower back, the extremities, other localized regions of the body, or the whole body despite ambient temperatures. It lasts throughout the year for most patients, and disturbs their daily living” [2].

Hie as a subjective symptom is common in Japanese people [1] and is more common in women [3]. However, the epidemiology of this symptom is not clear in Western people. One report comparing Japanese with Brazilians indicated that 57% of Brazilian pregnant women were aware of cold sensations [4]. We think it may be common symptom in other populations as well. In 1987, Kondo and Okamura reported demographic data of 318 Japanese women with hie but had no data for men [5]. They reported that hie accompanied other uncomfortable symptoms such as shoulder stiffness, constipation, lumbago, fatigue, and hot flushes. In Kampo medicine, treatments not only target hie, but also these accompanied symptoms. Subsequently, there are many Kampo formulas for treating hiesho.

Hie has been categorized into three types based on the body part where the symptoms are experienced. We assume different pathophysiology for each type. The first type of hie is a general type due to decreased heat production from a loss of muscle volume or decreased basal metabolism. The second type of hie is peripheral, due to a disturbance of heat distribution related to decreased peripheral blood flow. The third type of hie is upper body heat-lower body coldness with associated vasomotor abnormalities. However, epidemiological information regarding these classifications are unknown.

Keio University first introduced a browser-based questionnaire in 2008 that collects patient's subjective symptoms and changes in symptom severity via visual analogue scales (VAS), life styles, Western and Kampo diagnoses, and prescribed Kampo formulas.

Here, we report results from the analysis of data from male and female patients and attempt to clarify the characteristics associated with hie and hiesho. We especially focus on classification of hie and accompanied symptoms because this information is important for considering the pathophysiology of hie and the appropriate Kampo formulas for treating patients with hiesho.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Enrollment

Patients who made their first visit to the Kampo Clinic at Keio University Hospital between May 2008 and March 2013 were included from this study. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to enter the study and missing data regarding age and/or sex. Patients who answered only about their lifestyle or who were diagnosed as having hiesho but did not answer regarding the part of the body where they felt hie were excluded. All registered patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Patient Grouping

In this analysis, we divided patients into three groups: patients with hie with a diagnosis of hiesho (hiesho group), patients with hie without a diagnosis of hiesho (non-hiesho group), and patients without hie (Normal group). Our dataset did not include information about how physicians diagnosed patients with hiesho (Figure 1).

2.3. Assessment of Subjective Symptoms

We collected information about patients' subjective symptoms using a 128-question binary questionnaire (Table 1). Among these 128 questions, 106 also had VAS when patients answered yes on the binary questionnaire. The VAS was a horizontal line, 100 mm in length, where the left-most side (0 mm) represented no symptoms and right-most side (100 mm) represented the severest symptoms. To normalize within each patient, we divided each patient's VAS by the maximum VAS possible. This is because VAS scores were different from patient to patient. In other words, each patient's original VAS values ranged from 0 to 100 but were transformed to 0 to 1 for easier comparison.

Table 1.

Questionnaire items.

| No. | Binary questions | No. | Questions with visual analogue scales | No. | Questions with visual analogue scales |

|

| |||||

| 1 | Appetite loss | 1 | Difficulty falling asleep | 54 | Heat hands |

| Good appetite | 2 | Arousal during sleep | 55 | Heat legs | |

| 2 | Slow speed of the meal | 3 | Early-morning awakening | 56 | Edema face |

| Fast speed of the meal | 4 | Difficulty urinating | 57 | Edema hands | |

| 3 | I dream frequently | 5 | Urination pain | 58 | Edema legs |

| 4 | Single dose of urine large | 6 | Urine leakage | 59 | Headache |

| Single dose of urine low | 7 | Enuresis | 60 | Sluggishness | |

| 5 | Hard stool | 8 | Diarrhea | 61 | Vertigo |

| 6 | Small and round stool | 9 | Hemorrhoid | 62 | Lightheadedness |

| 7 | Soft stool | 10 | Anal prolapse | 63 | Dandruff |

| 8 | Hard to stool | 11 | Bloody stool | 64 | Hair loss |

| 9 | Taking laxatives | 12 | Depressed mood | 65 | Decreased visual acuity |

| 10 | White nasal discharge | 13 | Forgetfulness | 66 | Eyestrain |

| Yellow nasal discharge | 14 | Irritated | 67 | Blurred vision | |

| 11 | White sputum | 15 | Dry skin | 68 | Bleary eyes |

| Yellow sputum | 16 | Itchy skin | 69 | Dark circles under eyes | |

| 12 | Abdominal pain fasting | 17 | Acne | 70 | Sneezing |

| 13 | Abdominal pain after eating | 18 | Blot | 71 | Post nasal drip |

| 14 | Abdominal pain at upper | 19 | Urticaria | 72 | Stuffy nose |

| 15 | Abdominal pain at lower | 20 | Wart | 73 | Nosebleed |

| 16 | Heavy menstrual flow | 21 | Athlete's foot | 74 | Mouth bitter |

| Less menstrual flow | 22 | Brittle nails | 75 | Saliva comes out | |

| 17 | Irregular menstruation | 23 | Get tired easily | 76 | Throat pain |

| 18 | Delivery | 24 | Easy to sweat | 77 | Throat jams |

| 19 | Spontaneous abortion | 25 | Night sweats | 78 | Thirsty |

| 20 | Induced abortion | 26 | Hot flush | 79 | Dry mouth |

| 21 | Abnormal bleeding | 27 | Heat intolerance | 80 | Dry lips |

| 22 | Pregnancy toxemia | 28 | Cold intolerance | 81 | Take water often |

| 29 | Attenuation of sexual desire | 82 | Tinnitus | ||

| 30 | Impotence | 83 | Hearing loss | ||

| 31 | Neck stiffness | 84 | Cough | ||

| 32 | Shoulder stiffness | 85 | Asthma | ||

| 33 | Back stiffness | 86 | Shortness of breath | ||

| 34 | Lower back stiffness | 87 | Palpitation | ||

| 35 | Facial pain | 88 | Chest pain | ||

| 36 | Hand pain | 89 | Burp | ||

| 37 | Foot pain | 90 | Heartburn | ||

| 38 | Shoulder pain | 91 | Epigastric jamming discomfort | ||

| 39 | Back pain | 92 | Nausea | ||

| 40 | Hip pain | 93 | Vomiting | ||

| 41 | Knee pain | 94 | Motion sickness | ||

| 42 | Numbness face | 95 | Stomach fullness | ||

| 43 | Numbness hands | 96 | Stomach rumbling | ||

| 44 | Numbness legs | 97 | Flatulence | ||

| 45 | Numbness back | 98 | Sleepy after eating | ||

| 46 | Trembling face | 99 | Abdominal pain | ||

| 47 | Trembling hands | 100 | Hand stiffness | ||

| 48 | Trembling legs | 101 | Lower extremities weakness | ||

| 49 | Hie general | 102 | Legs fluctuate | ||

| 50 | Hie hands | 103 | Legs spasms | ||

| 51 | Hie legs | 104 | Frostbite | ||

| 52 | Hie lower back | 105 | Menstruation textile | ||

| 53 | Heat face | 106 | Menstrual pain | ||

We collected patients' subjective symptoms using a 128-item binary questionnaire. Of these symptoms, 106 corresponded to VAS questions when patients provided an affirmative response.

2.4. Between Group Comparisons

We focused on symptoms directory related to hie to clarify the differences between the hiesho and non-hiesho groups. Here, we choose six symptoms from the directory related to hie: hie of the whole body, hie of the hands, hie of legs/feet, hie of the lower back, cold intolerance, and tendency to get frostbite.

We also analyzed body part combinations where patients felt hie and five heat-related symptoms to get epidemiological information regarding hie classification. The five heat-related symptoms were as follows: heat intolerance, hot flush, heat sensation of the face, heat sensation of the hands, and heat sensation of legs/feet.

Finally, we focused on accompanying symptoms and compared men and women to clarify differences between these groups.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software, version 2.15.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; October 26, 2012). Characteristics were compared using Wilcoxon's rank sum test, two-sample t-test, and test for equal proportions. We used Wilcoxon's rank sum test to compare the VAS of hie because normality did not hold. We used a significant level of 5% for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Information

Participants included 4,057 registered patients, 41 of whom were excluded because of missing values (one due to missing age, 19 failed to report anything regarding subjective symptoms, and 21 were missing data on the part of the body where they felt hie in spite of a diagnosis of hiesho). We used data from 4,016 patients in this analysis, including 2,344 patients with hie, and 524 of those who were diagnosed as having hiesho.

3.2. Age and Sex

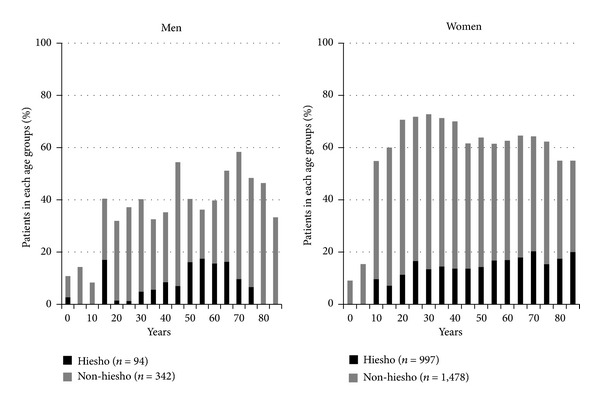

We compared age and sex of patients with hie with the diagnosis of hiesho (hiesho group, n = 524) and patients with hie but no diagnosis of hiesho (non-hiesho group, n = 1,820) to patients without hie (Normal group, n = 1,672). The mean age was 51.6 ± 1.5 years old for members of the hiesho group, 47.1 ± 0.8 years old for the non-hiesho group, and 46.2 ± 1.0 years old for the Normal group. Participant mean age in the hiesho group was significantly higher than the non-hiesho and Normal groups according to results of a t-test. The number of patients in each group who fell within each age group is shown in Figure 2. Hie and hiesho were uncommon in children and rates were similar for young and old patients.

Figure 2.

Rate of non-hiesho and hiesho groups in each age group. Hie (cold sensation) and hiesho (cold disorder) were uncommon in children, but almost similarly present among young and old patients. We also can see that hie and hiesho were more common in women.

With regard to sex, there were 94 men and 430 women (percentage of women: 82.1%) in the hiesho group, 342 men and 1,478 women (percentage of women: 81.2%) in the non-hiesho group, and 675 men and 997 women (percentage of women: 59.6%) in the Normal group. A test for equal proportions showed significantly more women in both the hiesho and non-hiesho groups than in the Normal group.

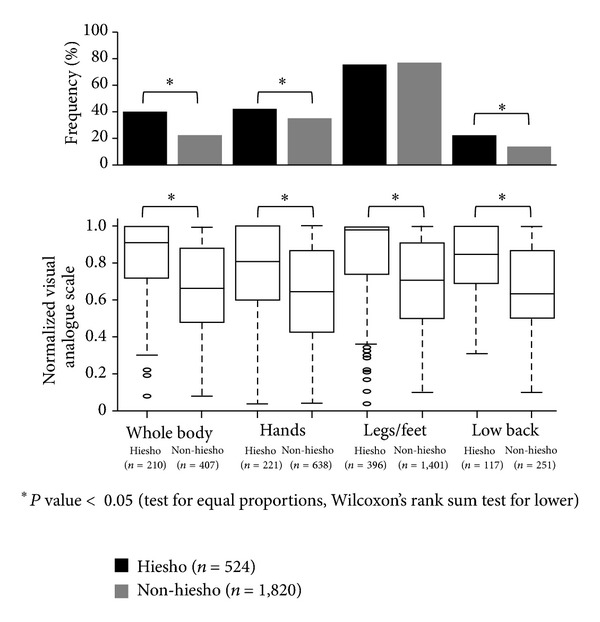

3.3. Differences between Hiesho and Non-Hiesho Groups

We compared the location where hie symptoms occurred between the three groups. The frequencies of binary answers for the four parts of the body where patients felt hie for hiesho and non-hiesho groups are as follow: hie of the whole body: hiesho 40.1%, non-hiesho 22.4%; hie of the hands: hiesho 42.2%, non-hiesho 35.1%; hie of the legs/feet: hiesho 75.6%, non-hiesho 77.0%; and hie of the lower back: hiesho 22.3%, non-hiesho 13.8%. Except for legs/feet, the frequencies of hie were significantly higher for the hiesho group based on results of the test for equal proportions (Figure 3 upper). There were no clear differences seen regarding the distribution of hie based on patient age or sex.

Figure 3.

Frequency and severity of hie (cold sensation) by affected areas. The frequencies of binary answers of four parts of the body where patients felt hie were significantly higher in hiesho group except for hie of legs/feet as per the test for equal proportions (upper figure). Normalized visual analogue scales of hie of each body part of hiesho group were compared to non-hiesho group by Wilcoxon's rank sum test. Hie in every part of the body was significantly worse in hiesho group (lower figure).

The frequencies of binary answers of the other two hie related symptoms for all three groups are as follows: cold intolerance: hiesho 77.7%, non-hiesho 58.0%, and Normal 16.1%; and tendency to get frostbite: hiesho 10.7%, non-hiesho 6.3%, and Normal 1.5%. The frequencies of binary answers of the two symptoms were significantly higher in the hiesho group than the non-hiesho group, which were both higher than Normal group as determined by the test for equal proportions. We also compared the differences of VAS scores for hie of each body part for members of the hiesho and non-hiesho groups using Wilcoxon's rank sum test. For every part of the body, hie was significantly worse for members of the hiesho group (Figure 3 lower). In the same way, VAS values for cold intolerance in the hiesho group also were higher than those in the non-hiesho group, which were higher than those in the Normal group.

3.4. Body Part Combinations of Hie and Frequencies of Heat-Related Symptoms

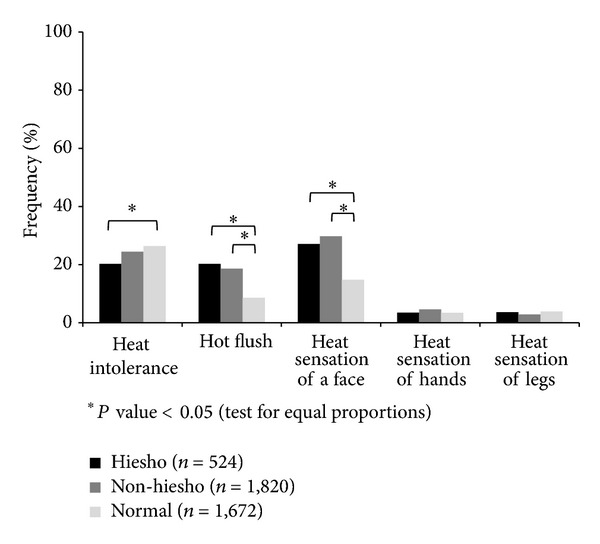

We also analyzed body part combinations where patients felt hie and frequencies of heat-related symptoms to obtain epidemiological information regarding the classification of hie. Regarding body part combination of hie symptoms for patients in the hiesho and non-hiesho group (n = 2,344), 722 patients felt hie in both their hands and legs/feet among 859 patients who felt hie in their hands; that is, 84.2% of patients who felt hie in their hands also felt hie in legs/feet. Similarly, among 368 patients who felt hie in their lower back, 286 (77.7%) also felt hie in their legs/feet. In contrast, among the 617 patients who felt hie throughout their whole body, 265 (43.0%) also felt hie in their legs/feet and this ratio was significantly lower than the former two as determined by the test for equal proportions (Table 2). We also focused on five heat-related symptoms for the three groups: heat intolerance: hiesho 20.2%, non-hiesho 24.5%, and Normal 26.4%; hot flushes: hiesho 20.2%, non-hiesho 18.6%, and Normal 8.6%; heat sensation in the face: hiesho 27.1%, non-hiesho 29.8%, and Normal 14.8%; heat sensation in the hands: hiesho 3.4%, non-hiesho 4.6%, and Normal 3.4%; and heat sensation of the legs/feet: hiesho 3.6%, non-hiesho 2.9%, and Normal 3.9% (Figure 4). We did not separate these groups by sex, as men in the hiesho and non-hiesho groups had higher frequencies of hot flush or heat sensation of the face the same as women in hiesho group or non-hiesho group. The frequency of heat intolerance was significantly lower for the hiesho group compared to Normal group. In contrast, hot flush and heat sensation of the face were significantly more frequent for members of the hiesho and non-hiesho groups compared to the Normal group as indicated by the test for equal proportions.

Table 2.

Number of patients with hie (cold sensation) as per combination of body parts (%).

| Whole body (n = 617) | Hands (n = 859) | Legs (n = 1,797) | Lower back (n = 368) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole body | 617 (26.3) | |||

| Hands | 172 (7.3) | 859 (36.6) | ||

| Legs | 265 (11.3) | 722 (30.8) | 1,797 (76.7) | |

| Lower back | 126 (5.4) | 152 (6.5) | 286 (12.2) | 368 (15.7) |

This table shows the combination of body parts where patients with hie (n = 2,344, including hiesho and non-hiesho groups) experienced their symptoms. As you can see, 30.8% felt hie in both their hands and legs/feet; that is, 84.2% of patients who felt hie in their hands also felt hie in legs/feet. Similarly, 12.2% felt hie in both their lower back and legs/feet; that is, 77.7% of patients who felt hie in their lower back also felt hie in legs/feet. In contrast, 11.3% of patients felt hie throughout their whole body and legs/feet; that is, 43% of patients who felt hie throughout whole body also felt hie in their legs/feet; this ratio was significantly lower than the former two.

Figure 4.

Heat symptoms for non-hiesho and hiesho groups. The frequencies of binary answers about upper body heat symptoms, such as hot flushes and heat sensation of the face, were significantly common in patients with hie (cold sensation). All data were compared using the test for equal proportions.

3.5. Accompanying Symptoms

We also compared accompanying symptoms in members of the three groups. Of 122 symptoms, after removing the 6 hie related symptoms, the mean number of subjective symptoms reported was 22.9 ± 1.0 for members of the hiesho group, 24.5 ± 0.6 for the non-hiesho group, and 15.8 ± 0.5 for the Normal group (Table 3). The mean number of subjective symptoms for both the hiesho and non-hiesho groups was significantly higher compared to the Normal group as indicated by the t-test. We sorted symptoms by reporting frequency for the hiesho group. The top 10 common symptoms were as follows: shoulder stiffness, easily fatigued, neck stiffness, eyestrain, depressed mood, constipation, upper back stiffness, dry skin, flatulence, and forgetfulness. In women, menstrual pain also was common. The ranking of these symptoms was almost the same for members of both sexes and all three groups.

Table 3.

Ten most commonly associated symptoms for patients in the hiesho (cold disorder) group and frequencies in other groups.

| Hiesho (n = 524) | Non-hiesho (n = 1,820) | Normal (n = 1,672) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of accompanied symptoms ± SD | 22.9 ± 1.0 | 24.5 ± 0.6 | 15.8 ± 0.5 |

| Common symptoms (women [%]/men [%]) | |||

| Shoulder stiffness | 338 (78.6)/56 (59.6) | 1152 (77.9)/196 (57.3) | 633 (63.5)/274 (40.6) |

| Easily fatigued | 306 (71.2)/53 (56.4) | 1071 (72.5)/212 (62.0) | 562 (56.4)/311 (46.1) |

| Neck stiffness | 283 (65.8)/43 (45.7) | 970 (65.6)/168 (49.1) | 466 (46.7)/200 (29.6) |

| Eyestrain | 249 (57.9)/35 (37.2) | 808 (54.7)/175 (51.2) | 425 (42.6)/222 (32.9) |

| Depressed mood | 186 (43.3)/31 (33.0) | 721 (48.8)/139 (40.6) | 338 (33.9)/183 (27.1) |

| Constipation | 174 (40.5)/26 (27.7) | 631 (42.7)/93 (27.2) | 339 (34.0)/140 (20.7) |

| Upper back stiffness | 172 (40.0)/25 (26.6) | 577 (39.0)/98 (28.7) | 240 (24.1)/84 (12.4) |

| Dry skin | 164 (38.1)/27 (28.7) | 624 (42.2)/140 (40.9) | 334 (33.5)/247 (36.6) |

| Flatulence | 154 (35.8)/35 (37.2) | 510 (34.5)/135 (39.5) | 247 (24.8)/162 (24.0) |

| Forgetfulness | 145 (33.7)/42 (44.7) | 499 (33.8)/124 (36.3) | 283 (28.4)/153 (22.7) |

| Menstrual pain | 156 (36.3)/0 (0.0) | 580 (39.2)/0 (0.0) | 239 (24.0)/0 (0.0) |

The mean number of subjective symptoms from 122 symptoms for both hiesho and non-hiesho groups was significantly higher compared to normal group as shown by the t-test. We sorted symptoms by frequency in the hiesho group. The ranking of these symptoms was almost the same between the three groups and by participants' sex. Almost all symptoms were more common in the hiesho and non-hiesho groups compared to the normal group. In women, menstrual pain also was common. Results may be affected by the number of symptoms reported by patients.

4. Discussion

Kampo physicians diagnose patients as having hiesho (cold disorder), when hie (cold sensation) and its associated symptoms cause disturbance in daily living. In Japanese Kampo medicine, hiesho is treated as a unique pathological condition and there are many Kampo formulas to treat it. When choosing Kampo formulas, the part of the body where hie and its accompanied symptoms are felt is important. This is why the present study has focused on the classification of hie and its comorbid symptoms.

Fundamental parts of our dataset were consistent with previous reports and supported the generalizability of our data, despite our population being recruited from a Kampo clinic. It has been reported that the subjective symptom of hie was common in Japanese people and a diagnosis of hiesho was common in Japanese Kampo clinics [1, 6]. Consistent with these past reports, around 60% of patients in our study reported subjective feelings of hie, and hiesho was one of the most common diagnoses in the Kampo medicine clinic where our study was conducted. It also has been reported that hie and hiesho are common in women [3], which is consistent with results of the present study. The frequency of patients in our study who reported experiencing hie in their extremities was also consistent with the results of past studies from an obstetrics-and-gynecology clinic in Japan [7] and on working women in Japan [5]. Ushiroyama mentioned that women developed hie because of the existence of their pelvic organs, which affected peripheral blood flow to the legs/feet and lower back [7]. Women's pelvic organs develop after puberty and may consume blood flow of lower body. However, according to our research, the legs/feet were the most common parts of the body affected by hie for both men and women of all age groups. Thus, explanations regarding the effect of pelvic organs do not help us understand lower body hie in men and postmenopausal women.

We found that patients diagnosed as having hiesho reported more severe hie symptoms. The frequencies of hie of the whole body, hands, and lower back as well as reports of cold intolerance and a tendency to get frostbite were higher in the hiesho compared to non-hiesho group. Furthermore, patients in the hiesho group were more likely to have high VAS scores regarding hie for any body part and cold intolerance compared to their non-hiesho counterparts. There were no other symptoms for which patients in the hiesho group had higher VAS scores than those in the non-hiesho group. In addition, hypothyroidism was significantly more common in the hiesho than non-hiesho group (2.5% versus 0.7%); however, most patients in the hiesho group did not have organic diseases that might cause hie (data not shown). It might be important for us to not only treat hiesho, but also to study organic diseases that can cause hie, especially in members of the hiesho group.

One classification categorizes hie into the three as per the areas of the body where people report experiencing it: general, peripheral, and upper body heat-lower body coldness. At the 51st annual meeting of the Japan Society for Oriental Medicine, Kako Watanabe et al. reported the efficacy of the cold-water challenge test to divide hie into these three types (not published). They put patients' hands into cold water at 4°C for 30 seconds and measured blood flow recovery. Patients with decreased metabolism complained of whole body hie after the cold-water challenge despite normal blood flow recovery, and patients with disturbed peripheral blood flow could not recover blood flow after the cold-water challenge test. In addition, patients with upper body heat-lower body coldness recovered blood flow with fluctuation due to autonomic imbalance. In Kampo theory, the pathophysiology of these three types of hiesho has been explained as qi deficiency, blood stagnation, and qi counterflow.

Our results support this classification of hie. We observed that many patients who report feeling hie in their hands or lower back also felt it in their legs/feet, and these combinations were far more frequent than the combination of whole body and legs/feet. The result supports the first two types of hie (general and peripheral). Our results also suggest that the peripheral type might be further subdivided by the type of extremity (e.g., narrowly defined extremity type, which affected hands and legs/feet, and lower body type, which affected the lower back and legs/feet). The general type of hie is thought to be related to a loss of heat production from decreased muscle volume and/or basal metabolism, and peripheral hie may be due to disturbances in heat distribution due to blood stagnation. We also found that around 20–30% of patients with hie felt upper body heat sensations such as hot flushes and heat sensation of the face, and these symptoms were significantly more common in patients with hie. This supports the existence of upper body heat-lower body coldness. This type of hie may be related to a kind of autonomic imbalance that causes vasomotor disturbances.

We assume representative Western diagnosis for these three types of hie. First, one of the organic diseases that causes general hie is hypothyroidism. Due to low metabolism, patients complain about feeling cold or cold intolerance, which sometimes may be comorbid with objectively cool peripheral extremities [8]. Based on a randomized crossover trial, thyroxin did not appear effective for patients with normal thyroid function tests and symptoms of hypothyroidism including intolerance to cold [9]. Next, one of the organic diseases that causes peripheral hie is peripheral arterial disease due to arteriosclerosis [10]. It is a good adaptation of Western intervention when patients feel acute coldness with resting pain in their foot and toes by critical limb ischemia such as occlusion of an artery where blood flow cannot accommodate basal nutritional needs of the tissues [11]. However, the majority of patients feel chronic cold sensations in their legs/feet without gait disturbances and it is difficult to treat such patients in Western medicine. Finally, one of the organic diseases that causes upper body heat-lower body coldness is perimenopausal disturbance. Hot flushes with lower extremity coldness due to vasomotor disturbance is common for peri- or postmenopausal women [12]. Treatment options are limited for some patients due to side effects of hormone replacement therapy. Kampo medicine may be one treatment option for such patients and we try to apply the appropriate Kampo formulas.

Our data supported that patients with hie experienced many uncomfortable symptoms, which may be aggravated by hie. It has been reported that women with hie and hiesho experienced other uncomfortable symptoms such as shoulder stiffness, constipation, lumbago, fatigue, hot flush, headache, and edema in the leg [3, 5]. Our findings support these results for both the sexes; menstrual pain often was found in women with hie. Thus, treatment of hie may lead to not only its improvement, but also to the improvement of other symptoms. However, the number of symptoms experienced by patients might affect our results, as patients with hie reported about 10 more symptoms than those without hie. This suggests that patients with hie had 1.6–1.8 times more symptoms than patients without hie. We also can assume that hie is an indicator of patients with many symptoms. Thus, we may obtain more information by segregating patients with hie according to their comorbid symptoms.

5. Conclusion

The present study is important because it clarifies some of the epidemiological characteristics of patients with hie and hiesho. Specifically, we have learned the following. (1) hiesho patients are those who suffer from severe hie. (2) Patients with hie may be classified roughly into three types. (3) Patients with hie experience many comorbid symptoms. (4) Men and women with hiesho have almost the same distribution of hie and its associated symptoms. Appropriate treatment options for hiesho are not available in Western medicine. Therefore, if we are more aware of hiesho, we can use Kampo formulas to treat not only the patients' hie, but their comorbid symptoms as well.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Research on Propulsion Study of Clinical Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

References

- 1.Ishino S. Kampo medicine for Outpatients clinic. Sanfujinka Chiryo Obstetrical and Gynecological Therapy. 2001;82(3):344–348. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terasawa K. On the recognition and treatment of “Hie-sho” (chillphobia) in the traditional Kampoh medicine. Shoyakugaku Zasshi. 1987;41(2):85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imai M, Akasofu K, Fukunishi H. A study on the factors and awareness of the cold sensation of the adult females. Ishikawa Journal of Nursing. 2007;4:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura S, Ichisato SM, Horiuchi S, Mori T, Momoi M. Pregnant women’s awareness of sensitivity to cold (hiesho) and body temperature observational study: a comparison of Japanese and Brazilian women. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4, article 278 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondo M, Okamura Y. Cold constitution: analysis of the questionnaire. Acta Obstetrica et Gynaecologica Japonica. 1987;39(11):2000–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Kim N, Ogata C. A study on the actual use of Western medicine in patients taking Japanese traditional herbal medicine. Yakujishinpo. 2009;01(2560):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ushiroyama N. Chill sensation: pathological findings and its therapeutic approach. Journal of Clinical and Experimaental Medicine. 2005;215(11):925–929. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jameson JL, Weetman AP. Diseases of thyroid gland. In: Kasrer DL, Braunwald E, Hauser S, Longo D, Larry Jameson J, Fauci AS, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th edition. Singapore: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 2104–2127. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollock MA, Sturrock A, Marshall K, et al. Thyroxine treatment in patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism but thyroid function tests within the reference range: randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover trial. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7318):891–895. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47(6):1239–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creager MA, Dzau VJ. Vascular diseases of extrimities. In: Kasrer DL, Braunwald E, Hauser S, Longo D, Larry Jameson J, Fauci AS, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th edition. Singapore: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1486–1494. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Bartoces M, Neale AV, Dailey RK, Northrup J, Schwartz KL. Natural history of menopause symptoms in primary care patients: a MetroNet study. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18(5):374–382. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.5.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]