Abstract

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumor of infancy, yet its pathogenesis and the mechanisms governing proliferation and involution are not well understood. It is believed that hemangiomas arise out of clonal, abnormal hemangioma endothelial cells (HemECs). The underlying anomaly of the HemEC is not known, although studies have shown that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF signaling may influence HemECs. Moreover, there are numerous subtypes of hemangiomas, with differences in natural history, potential for morbidity, and prognosis, and little is known how this relates to HemEC. The Notch signaling pathway is a highly conserved pathway across species from worms to mammals. Notch signaling has been shown to play a role during embryogenesis in directing vascular patterning and development and arterial and venous cell fate determination. Postnatally, it has been implicated in tumor angiogenesis in multiple malignancies. Notch signaling triggers tumor angiogenesis at least in part to stimulation by VEGF, thus establishing that there is a cross talk between the VEGF and Notch pathways. Given the presence of VEGF and its receptors in hemangiomas and known VEGF-Notch cross talk in tumor angiogenesis, the authors hypothesize that Notch signaling may contribute to hemangioma proliferation and involution. Preliminary studies of resected hemangioma specimens by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) show that all 4 Notch receptors and 2 Notch ligands, Jagged1 and Delta-like ligand 4, are expressed by hemangiomas. These findings support a role for Notch in hemangiomas, meriting further analysis of the functional relevance of Notch signaling in hemangiomas.

Keywords: Hemangioma, Notch signaling, angiogenesis, vasculogenesis

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common benign tumor of infancy, affecting up to 4% to 10% of infants,1,2 yet its pathogenesis is incompletely understood. Although the natural history is well described and various subtypes of hemangiomas have been studied and classified,3-5 the etiology, pathogenesis, and genetics of hemangiomas are not known.2 The hemangioma endothelial cell (HemEC) and its precursor, the hemangioma endothelial progenitor cell (HemEPC), have been isolated from resected specimens and studied.6-9 However, its origin and underlying anomaly are not well understood, although studies have looked at the potential role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor (VEGF-R2).10,11 In addition to the poor understanding of its origin, there is also a limited knowledge in the molecular mechanisms governing the proliferation and involution of hemangiomas.

Recently, the role of the Notch signaling pathway in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis has been studied in detail.12,13 Notch signaling plays a role in cell fate determination during embryogenesis,14,15 arterial and venous differentiations during vasculogenesis,16 and tumor angiogenesis postnatally.17-25 Moreover, Notch signaling is known to interact with VEGF-R2.26 It is therefore plausible that Notch signaling plays a role in hemangioma—a tumor of endothelial cells (ECs)—proliferation and involution.

Hemangiomas: Natural History and Subtypes

Infantile hemangiomas develop at or shortly after birth and proliferate for 8 to 10 months; involution begins at approximately 12 months of age.1 However, this time range shows more variability than previously thought.27 More recent clinical studies have shown that the most aggressive proliferation occurred in the first 6 months of life (Chang, personal communication); on the other hand, proliferation persisting beyond the first year of life has also been observed (Garzon and Frieden, personal communication).

Most IHs are asymptomatic, but potential morbidities during proliferation can be severe. For example, deprivation amblyopia or astigmatism may result from eyelid hemangioma28,29 and airway compromise from subglottic hemangiomas.30 Rapid growth during the proliferative phase may lead to ulceration and bleeding requiring transfusion or urgent surgical intervention. Liver hemangiomas have a reported overall 18% mortality rate during the proliferative phase.31

Not all hemangiomas follow this homogeneous course of natural history. A subtype of hemangioma—termed congenital hemangiomas—has been described. Unlike the more familiar IH, these congenital hemangiomas are fully formed at birth. They are further subdivided into rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas. They are large and can lead to high-output congestive heart failure3,32 requiring medical treatment. They are also at risk for bleeding and ulcerations requiring urgent embolization and/or surgical resection.

More recently, hemangiomas have been described as part of the posterior fossa, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, eye anomalies, and sternal cleft/raphe (PHACES) syndrome. The facial hemangiomas are large (termed segmental or diffuse). Infants with large facial hemangiomas as part of the PHACES syndrome are at risk for cerebral infarction.33,34 Even after complete involution of the hemangiomas, the cerebral and other anomalies persist.

Two recent studies describe a group of hemangiomas that fail to proliferate. These hemangiomas are similar to IH in that they develop shortly after birth; however, these hemangiomas lack the rapid and dramatic proliferation seen in IHs and do not form a protrusive tumor but remain macular. These hemangiomas have been termed abortive27 or reticular35 hemangiomas. The abortive hemangiomas were small and had no systemic effects.27 However, the reticular hemangiomas—described as reticular IHs of the limb—had other associated anomalies, such as anogenital anomalies and ulceration over the hemangioma requiring aggressive intervention. The authors in that report have proposed that this type of reticular hemangiomas may be analogous to the PHACES syndrome.35 A similar pattern of flat, perineal hemangioma with underlying genitourinary anomalies has also been described.36 The natural history of this subtype of hemangiomas has not been described. Whether these should be considered IHs or classified as a completely different subtype of hemangiomas remains to be investigated.

Interestingly, both the PHACES syndrome and the reticular IH of the limb and perineum have other associated anomalies. Hemangiomas associated with the underlying vasculopathies suggest that the pathogenesis of hemangiomas may be embryologically related to the vascular development in utero. This potential relationship has not been studied, but it may yield insight into potential pathogenetic mechanisms. Interestingly, Notch signaling plays a significant role in vascular development and patterning in utero.12,13

Lack of an Animal Model to Study Hemangioma

One of the major impediments to the study of hemangiomas is the lack of a true animal model. Although there have been published reports of animal models of hemangiomas, these exhibit limitations that do not allow them to recapitulate the proliferation and involution of clinical IHs. One of the oldest, most well-known hemangioma mouse model was established by direct injection of polyoma virus middle T–transformed DNA37 or polyoma virus middle T–transformed ECs to form tumors.38 However, histologic appearance of these lesions after removal from the animals was different from those of human hemangiomas. Others have reported a mouse model based on implantation of excised hemangiomas.39 However, these rely on using excised specimens and are involuted in a few months’ time, so the window of time for studies to be performed is limited because the implanted human hemangiomas became fibrotic. Other variations include the injection of estrogen into the mice to delay involution,40 yet the role and contribution of estrogen to hemangiomas is poorly understood.41,42 The most promising hemangioma has been reported from the laboratory of Dr Joyce Bischoff. These models use stem cells isolated from hemangiomas, which are then suspended in Matrigel and implanted into nude mice, and their subsequent growth is monitored.43

Molecular and Genetic Studies on Hemangiomas

Despite their prevalence, the origin of hemangiomas and the signals that mediate proliferation and involution of these lesions are still not well understood1,44,45 and under debate. A report that there was phenotypic similarity by immunohistochemistry between hemangioma and placental ECs46 led to a theory of placental origin of hemangiomas.47,48 Other placental anomalies, such as preeclampsia and placenta previa, have been linked to increased risk for hemangiomas.49 Histologic examination of placentas from premature births also revealed histologic anomalies, notably areas of infarctions.50 There have also been reports that infants whose mothers underwent chorionic villous sampling had higher incidences of having hemangiomas.51 Finally, Barnes et al52 showed that HemECs share similar molecular profile with placental ECs. However, there was no conclusive evidence definitively ascribing HemECs to a placental origin. Other theories speculated on the role of hormones and hypoxia. Hypoxia has been implicated in the proliferation of hemangiomas.41,53 Interestingly, hypoxic conditions have been known to enhance Notch activation.54 However, definite proof of the origin of hemangiomas remain elusive,45 although the hemangioma stem cell isolated by Khan et al43 can differentiate and form groups of vessels in an animal model and suggests strongly that experimental hemangiomas arise from this precursor cell.

Hemangioma EC and HemEPC are Unique and Different From Mature Adult ECs

Other investigators have concentrated on isolating the HemECs for study in detail. Molecular studies have shown that these HemECs are clonal in origin.6 Recent studies have demonstrated some inherent differences between HemECs and normal adult ECs.6,9,55 For instance, HemECs demonstrate increased migratory activity when challenged with the angiogenic inhibitor endostatin.6 Further studies have shown that in addition to increased migration, both HemECs and HemEPCs exhibit increased adhesion and proliferation to endostatin; however, this is not unique to HemECs and HemEPCs because umbilical cord blood EPCs also show this abnormal response to endostatin.9 Taken together, these data suggest that this anomaly seen in HemEPCs and HemECs is not a unique feature of hemangiomas per se, but is a feature of all immature ECs. It also raises the possibility that the development of HemECs is a result of an abnormal differentiation from HemEPCs. This would be consistent with an earlier histologic study that suggested that HemECs retained immature immunophenotype.56 This ability of mature HemECs to retain immature molecular features of the endothelial progenitor cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of hemangiomas.

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 May Play a Role in Hemangioma Proliferation

Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potent proangiogenic factor. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes survival and proliferation of ECs.57 Several studies reported increased VEGF expression in proliferating versus involuting hemangiomas, using immunohistochemical staining10 and in situ hybridization probing for VEGF messenger RNA expression.58 However, subsequent studies have not verified that claim, and analyses of messenger RNA expression of VEGF in hemangiomas actually showed minimal VEGF expression, although the presence of VEGF-R2 (kinase insert domain receptor) is increased.55 Furthermore, one study found 2 mutations in 2 hemangioma specimens (in VEGF-R2 and VEGF-R3, respectively) of 15 specimen studies, suggesting that VEGF-R may be involved in the pathogenesis of hemangiomas.11

These data suggest that the VEGF-R pathway may play a role in hemangioma proliferation, although this process is not necessarily dependent on VEGF. Whether VEGF-R signaling is mediated via another, yet unidentified ligand, or whether it is constitutively active in hemangiomas, remains to be studied.

Notch Receptors are Involved in Arterial Differentiation and Vascular Development During Fetal Development

Notch signaling is a highly conserved pathway that has a proven role in cellular differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis, especially in development of the vasculature.12,59,60 There are 4 known Notch receptors (Notch1-4)61-65 and 5 ligands (Delta-like1 [Dll4], 3, and 4 and Jagged1 and 2).66-70 Notch proteins are transmembrane receptors. The extracellular portion consists of epidermal growth factor–like repeats and 3 cystein-rich repeats.64 The intracellular portion consists of 6 ankryin repeats, a RAM (RBP-J associated molecule) domain, and a PEST (proline, glutamate, serine, and threonine-rich) domain in the C terminal.19 The extracellular portion binds to the ligand, upon which the intracellular portion of Notch is released and translocates to the nucleus to activate transcription factors downstream.71 In particular, Notch1 and 4 are involved in embryological vascular development, mediating arterial/venous differentiation.60 The presence of Notch1 and 4 has been shown to be restricted to the arterial but not venous ECs in mouse embryo64 and are believed to play a role in determining arterial/venous cell fate during fetal vascular development.

Notch is Involved in Postembryological Processes

Besides fetal development, Notch signaling has been shown to be up-regulated during postnatal physiological processes. One example is its involvement in tumor angiogenesis in multiple tumors, inhibiting apoptosis and promoting proliferation.24 Activated Notch may be causative in the development of breast cancer in a mouse model of mammary cancer induced by a virus.18 Examination of human breast tissue with in situ hybridization and microarray analyses demonstrated that Notch1 and Jagged1 were present in human breast cancer tissues, with a positive correlation between high levels of Notch and Jagged1 in tumors with unfavorable histologic features and poorer clinical survival.19,21 In vitro analyses of human tumor tissues have shown that Dll4 is up-regulated in human clear cell renal cell carcinoma22 and Jagged1 is associated with prostate cancer recurrence and metastasis.17

More recently, Notch signaling has been shown to play a role in wound healing.72 Both in vivo and in vitro studies showed that Notch was involved in multiple cells during wound healing, including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and ECs.

Therefore, Notch and its ligands are not only expressed during fetal development but also play a role in postnatal physiological and pathologic conditions.

Cross Talk Between VEGF and the Notch Signaling Pathway

Multiple studies have shown that the VEGF signaling pathway interacts with and regulates the Notch signaling pathway in the promotion of proangiogenic or antiangiogenic environment. In mice and zebra fish, Notch has been placed downstream of VEGF in the process of arterial specification.73 Studies have shown that VEGF-A (or VEGF) induced the expression of Notch1 in human iliac artery ECs in vitro, and the effect of VEGF in promoting EC survival and vascular network formation is partially mediated through Notch signaling, via VEGF-R-1 and VEGF-R-2.74 Recent studies in the Kitajewski laboratory also showed activation of VEGF-R-3 by Notch1 in the promotion cardiovascular development.26

In vitro cell culture studies have shown that VEGF induces the Notch ligand Dll4, which in turn activates Notch receptor signaling, which may be 1 mechanism through which Notch mediates tumor angiogenesis.22,75 Delta-like4 and Notch are involved in sprouting angiogenesis in response to VEGF in a mouse retina angiogenesis model.76-78 On the other hand, activation of Dll4 may in turn function as a negative feedback loop to this pathway. Human umbilical vein ECs transfected to overexpress Dll4 actually shows decreased proliferative and migratory responses to VEGF-A, in part by decreased expression of VEGF-R and a coreceptor.79

More recent studies using molecular blockade of Notch signaling demonstrated inhibition of angiogenesis via Notch ligands Dll4 and Jagged1. In addition, this angiogenic inhibition extended to VEGF-induced angiogenesis, further pointing to the interaction between VEGF stimulation of Notch-mediated angiogenesis.25

Taken together, these data demonstrate the cross talk between VEGF and Notch under both physiological and pathologic conditions. The VEGF activates the Notch signaling cascade in ECs through VEGF-R. Because increased expression of VEGF-R has been shown in hemangioma tissues during proliferation, the VEGF-R signaling pathway may play a role in the proliferation of hemangiomas via Notch signaling.

Notch Receptors and Ligands are Present in Hemangiomas

To test the hypothesis that VEGF-R signaling is mediated through the Notch cascade, the presence of Notch ligands and receptors was investigated in hemangiomas.

Institutional review board approval to the study was obtained from the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (#AAAA9976). Resected hemangioma tissues were analyzed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Complementary DNA was prepared using a standardized reverse transcription protocol. The presence of complementary DNA was confirmed with β actin. Transcript levels of Notch receptors and ligands were primed and normalized to β actin.

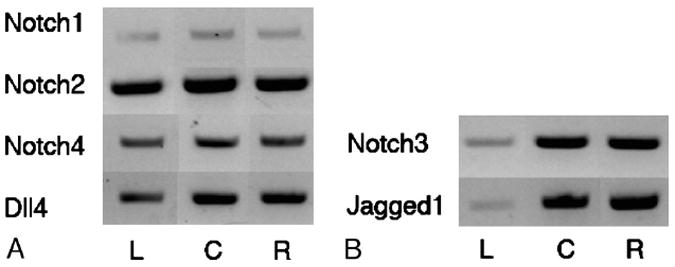

Preliminary studies of proliferating and involuting hemangioma tissues by RT-PCR showed that hemangiomas expressed all 4 Notch receptors (Notch1-4) and 2 ligands, Jagged1 and Dll-4 (Fig. 1). This was confirmed by immunohistochemistry.

FIGURE 1.

A, Left (L), human umbilical vein EC; center (C), proliferating hemangioma; and right (R), involuting hemangioma. Notch1, Notch4, and Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) were expressed in hemangioma, detected by RT-PCR. B, In addition, Notch3 and Jagged1 are strongly expressed in both proliferating (middle) and involuting (right) hemangiomas but only minimally in human umbilical vein ECs.

CONCLUSIONS

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumor of infancy, yet its pathogenesis and regulation of its natural history are poorly understood. The Notch signaling system plays a significant role in angiogenesis and vascular system development, and it is expressed in hemangiomas. It appears that normal or aberrant Notch signaling pathway may play a role in regulation of hemangioma biology. Elucidation of the role of Notch signaling in hemangiomas will provide insights into the pathophysiology of hemangiomas and the understanding of EC physiology in general.

References

- 1.Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Burrows PE. Vascular anomalies. Curr Probl Surg. 2000;37:517–584. doi: 10.1016/s0011-3840(00)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frieden IJ, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Infantile hemangiomas: current knowledge, future directions. Pediatr Dermatol; Proceedings of a research workshop on infantile hemangiomas; April 7–9, 2005; Bethesda, Maryland, USA. 2005. pp. 383–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boon LM, Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. Congenital hemangioma: evidence of accelerated involution. J Pediatr. 1996;128:329–335. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berenguer B, Mulliken JB, Enjolras O, et al. Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma: clinical and histopathologic features. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2003;6:495–510. doi: 10.1007/s10024-003-2134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enjolras O, Mulliken JB, Boon LM, et al. Noninvoluting congenital hemangioma: a rare cutaneous vascular anomaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1647–1654. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boye E, Yu Y, Paranya G, et al. Clonality and altered behavior of endothelial cells from hemangiomas. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:745–752. doi: 10.1172/JCI11432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bischoff J. Monoclonal expansion of endothelial cells in hemangioma: an intrinsic defect with extrinsic consequences? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:220–224. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y, Flint AF, Mulliken JB, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells in infantile hemangioma. Blood. 2004;103:1373–1375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan ZA, Melero-Martin JM, Wu X, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells from infantile hemangioma and umbilical cord blood display unique cellular responses to endostatin. Blood. 2006;108:915–921. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-006478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi K, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, et al. Cellular markers that distinguish the phases of hemangioma during infancy and childhood. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2357–2364. doi: 10.1172/JCI117241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter JW, North PE, Waner M, et al. Somatic mutation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in juvenile hemangioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33:295–303. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iso T, Hamamori Y, Kedes L. Notch signaling in vascular development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:543–553. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000060892.81529.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karsan A. The role of notch in modeling and maintaining the vasculature. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:14–23. doi: 10.1139/y04-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uyttendaele H, Soriano JV, Montesano R, et al. Notch4 and Wnt-1 proteins function to regulate branching morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells in an opposing fashion. Dev Biol. 1998;196:204–217. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vorontchikhina MA, Zimmermann RC, Shawber CJ, et al. Unique patterns of Notch1, Notch4 and Jagged1 expression in ovarian vessels during folliculogenesis and corpus luteum formation. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santagata S, Demichelis F, Riva A, et al. JAGGED1 expression is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and recurrence. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6854–6857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Politi K, Feirt N, Kitajewski J. Notch in mammary gland development and breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callahan R, Egan SE. Notch signaling in mammary development and oncogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;9:145–163. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000037159.63644.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Q, Li S, Chepeha DB, et al. Crosstalk between tumor and endothelial cells promotes tumor angiogenesis by MAPK activation of Notch signaling. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reedijk M, Odorcic S, Chang L, et al. High-level coexpression of JAG1 and NOTCH1 is observed in human breast cancer and is associated with poor overall survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8530–8537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel NS, Li JL, Generali D, et al. Up-regulation of Delta-like 4 ligand in human tumor vasculature and the role of basal expression in endothelial cell function. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8690–8697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leong KG, Karsan A. Recent insights into the role of Notch signaling in tumorigenesis. Blood. 2006;107:2223–2233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehman AO, Wang CY. Notch signaling in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Funahashi Y, Hernandez SL, Das I, et al. A Notch1 ectodomain construct inhibits endothelial Notch signaling, tumor growth, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4727–4735. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shawber CJ, Funahashi Y, Francisco E, et al. Notch alters VEGF responsiveness in human and murine endothelial cells by direct regulation of VEGFR-3 expression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3369–3382. doi: 10.1172/JCI24311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corella F, Garcia-Navarro X, Ribe A, et al. Abortive or minimal-growth hemangiomas: Immunohistochemical evidence that they represent true infantile hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ceisler E, Blei F. Ophthalmic issues in hemangiomas of infancy. Lymphat Res Biol. 2003;1:321–330. doi: 10.1089/153968503322758148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceisler EJ, Santos L, Blei F. Periocular hemangiomas: what every physician should know. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahbar R, Nicollas R, Roger G, et al. The biology and management of subglottic hemangioma: past, present, future. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1880–1891. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000147915.58862.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boon LM, Burrows PE, Paltiel HJ, et al. Hepatic vascular anomalies in infancy: a twenty-seven-year experience. J Pediatr. 1996;129:346–354. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell DM, Gumbiner CH, Martin GE. Congestive heart failure due to giant cutaneous cavernous hemangioma. Clin Pediatr. 1984;23:504–506. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burrows PE, Robertson RL, Mulliken JB, et al. Cerebral vasculopathy and neurologic sequelae in infants with cervicofacial hemangioma: report of eight patients. Radiology. 1998;207:601–607. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.3.9609880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drolet BA, Dohil M, Golomb MR, et al. Early stroke and cerebral vasculopathy in children with facial hemangiomas and PHACE association. Pediatrics. 2006;117:959–964. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulliken JB, Marler JJ, Burrows PE, et al. Reticular infantile hemangioma of the limb can be associated with ventral-caudal anomalies, refractory ulceration, and cardiac overload. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:356–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Girard C, Bigorre M, Guillot B, et al. PELVIS Syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:884–888. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.7.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Q, Zhang ZY, Chen WT, et al. The formation of transgenic mice with hemangiomas (in Chinese) Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;38:355–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothermel TA, Engelhardt B, Sheibani N. Polyoma virus middle-T–transformed PECAM-1 deficient mouse brain endothelial cells proliferate rapidly in culture and form hemangiomas in mice. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:230–239. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang Y, Liu W, Yu S, et al. A novel in vivo model of human hemangioma: xenograft of human hemangioma tissue on nude mice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:869–878. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000277661.49581.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng Q, Liu W, Tang Y, et al. The establishment of the hemangioma model in nude mouse. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1167–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang EI, Thangarajah H, Hamou C, et al. Hypoxia, hormones, and endothelial progenitor cells in hemangioma. Lymphat Res Biol. 2007;5:237–243. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun ZY, Yang L, Yi CG, et al. Possibilities and potential roles of estrogen in the pathogenesis of proliferation hemangiomas formation. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan ZA, Boscolo E, Picard A, et al. Multipotential stem cells recapitulate human infantile hemangioma in immunodeficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2592–2599. doi: 10.1172/JCI33493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulliken JB, Enjolras O. Congenital hemangiomas and infantile hemangioma: missing links. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.10.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ritter MR, Butschek RA, Friedlander M, et al. Pathogenesis of infantile haemangioma: new molecular and cellular insights. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2007;9:1–19. doi: 10.1017/S146239940700052X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.North PE, Waner M, Mizeracki A, et al. A unique microvascular phenotype shared by juvenile hemangiomas and human placenta. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:559–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.North PE, Waner M, Brodsky MC. Are infantile hemangiomas of placental origin? Ophthalmology. 2002;109:633–634. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnes CM, Christison-Lagay EA, Folkman J. The placenta theory and the origin of infantile hemangioma. Lymphat Res Biol. 2007;5:245–255. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, et al. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: demographic, prenatal, and perinatal characteristics. J Pediatr. 2007;150:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez Gutierrez JC, Avila LF, Sosa G, et al. Placental anomalies in children with infantile hemangioma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:353–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burton BK, Schulz CJ, Angle B, et al. An increased incidence of haemangiomas in infants born following chorionic villus sampling (CVS) Prenat Diagn. 1995;15:209–214. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970150302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnes CM, Huang S, Kaipainen A, et al. Evidence by molecular profiling for a placental origin of infantile hemangioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19097–19102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kleinman ME, Greives MR, Churgin SS, et al. Hypoxia-induced mediators of stem/progenitor cell trafficking are increased in children with hemangioma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2664–2670. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruas JL, Lendahl U, Poellinger L. Modulation of vascular gene expression by hypoxia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:508–514. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282efe49d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu Y, Varughese J, Brown LF, et al. Increased Tie2 expression, enhanced response to angiopoietin-1, and dysregulated angiopoietin-2 expression in hemangioma-derived endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2271–2280. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63077-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dadras SS, North PE, Bertoncini J, et al. Infantile hemangiomas are arrested in an early developmental vascular differentiation state. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1068–1079. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simons M. Integrative signaling in angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;264:99–102. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000044379.25823.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang J, Most D, Bresnick S, et al. Proliferative hemangiomas: analysis of cytokine gene expression and angiogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bicknell R, Harris AL. Novel angiogenic signaling pathways and vascular targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:219–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shawber CJ, Kitajewski J. Notch function in the vasculature: insights from zebrafish, mouse and man. Bioessays. 2004;26:225–234. doi: 10.1002/bies.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weinmaster G, Roberts VJ, Lemke G. A homolog of Drosophila Notch expressed during mammalian development. Development. 1991;113:199–205. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinmaster G, Roberts VJ, Lemke G. Notch2: a second mammalian Notch gene. Development. 1992;116:931–941. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lardelli M, Dahlstrand J, Lendahl U. The novel Notch homologue mouse Notch 3 lacks specific epidermal growth factor–repeats and is expressed in proliferating neuroepithelium. Mech Dev. 1994;46:123–136. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uyttendaele H, Marazzi G, Wu G, et al. Notch4/int-3, a mammary proto-oncogene, is an endothelial cell-specific mammalian Notch gene. Development. 1996;122:2251–2259. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gallahan D, Callahan R. The mouse mammary tumor associated gene INT3 is a unique member of the NOTCH gene family (NOTCH4) Oncogene. 1997;14:1883–1890. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bettenhausen B, Hrabe de Angelis M, Simon D, et al. Transient and restricted expression during mouse embryogenesis of Dll1, a murine gene closely related to Drosophila Delta. Development. 1995;121:2407–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dunwoodie SL, Henrique D, Harrison SM, et al. Mouse Dll3: a novel divergent Delta gene which may complement the function of other Delta homologues during early pattern formation in the mouse embryo. Development. 1997;124:3065–3076. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shutter JR, Scully S, Fan W, et al. Dll4, a novel Notch ligand expressed in arterial endothelium. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1313–1318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lindsell CE, Shawber CJ, Boulter J, et al. Jagged: a mammalian ligand that activates Notch1. Cell. 1995;80:909–917. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shawber C, Boulter J, Lindsell CE, et al. Jagged2: a serrate-like gene expressed during rat embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1996;180:370–376. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weinmaster G. Notch signaling: direct or what? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:436–442. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chigurupati S, Arumugam TV, Son TG, et al. Involvement of notch signaling in wound healing. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lawson ND, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM. sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev Cell. 2002;3:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu ZJ, Shirakawa T, Li Y, et al. Regulation of Notch1 and Dll4 by vascular endothelial growth factor in arterial endothelial cells: implications for modulating arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:14–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.14-25.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hainaud P, Contreres JO, Villemain A, et al. The role of the vascular endothelial growth factor-Delta-like 4 ligand/Notch4-ephrin B2 cascade in tumor vessel remodeling and endothelial cell functions. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8501–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hellstrom M, Phng LK, Hofmann JJ, et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;445:776–780. doi: 10.1038/nature05571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lobov IB, Renard RA, Papadopoulos N, et al. Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) is induced by VEGF as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3219–3224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611206104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suchting S, Freitas C, le Noble F, et al. The Notch ligand Delta-like 4 negatively regulates endothelial tip cell formation and vessel branching. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3225–3230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611177104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams CK, Li JL, Murga M, et al. Up-regulation of the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 inhibits VEGF-induced endothelial cell function. Blood. 2006;107:931–939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]