1. Introduction

Abuse of alcohol is a leading cause of preventable disease and death worldwide, affecting an estimated 76.3 million people [1]. Extensive research is being conducted on the development of alcohol use disorders, and a number of candidate genes have shown association with alcohol use [2]. Ethanol interacts with a variety of subcellular components comprising many of the known neurotransmitter systems including the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway [3–5]. It has been proposed that a common pathway exists for addiction, and cross-tolerance between drugs of abuse, as well as co-abuse has been observed [5].

McMillan (1978) was the first to report the behavioral interaction of exercise and ethanol [6,7]. Since then, several groups have shown that access to exercise can influence voluntary ethanol intake [8–10]. Recent work in our laboratory supported the hypothesis that wheel-running may influence the reinforcing effects of ethanol [11]. This concept of hedonic substitution has been implemented in exercise intervention programs for humans consuming high quantities of ethanol [12–16]. Furthermore, the effects of exercise may not be limited to ethanol, and could be extended to amphetamine [17], nicotine [18] and cocaine [19].

While there is strong evidence that voluntary exercise can influence the consumption of ethanol, the mechanisms responsible for this interaction remain unclear. The mesolimbic dopaminergic (DA) pathway has been implicated in both ethanol consumption and exercise behaviors [3,20]. Both exercise and ethanol consumption acutely induce DA release in the striatum [20–23]. The mesolimbic DA pathway is composed of DA neurons originating in two sub-regions of the midbrain: substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA). These neurons project to the striatum—caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens—as well as to regions of the frontal cortex. Also important is the hippocampus, which modulates the role of the striatum based on contextual learning. We examined the gene expression of six genes important in regulating this pathway which have also been previously associated with exercise and/or ethanol consumption. Tyrosine hydroxylase (Th), the rate-limiting enzyme in the DA synthesis pathway, has been shown to be up-regulated in certain sub-regions of the VTA of rats exposed to exercise [24], as well as in response to acute ethanol in vivo [25]. We also examined two genes involved in DA release and reuptake. Solute carrier family 18 member a2 (Slc18a2) produces the vesicular monoamine transporter which packages cytosolic DA into synaptic vesicles, facilitating DA release. Solute carrier family 6 member a3 (Slc6a3) codes for the dopamine active transporter, which is responsible for the reuptake of synaptic DA. Neither of these genes has been studied at the neurophysiological level for response to exercise or alcohol. Variations in the human SLC18A2 and SLC6A3 genes have been associated with alcohol disorders [26–28]. There is conflicting evidence that female Slc18a2 knockout mice drink less ethanol [29,30], but Slc6a3 knockout mice do not show differences in voluntary alcohol consumption [29]. In addition, we consider the two genes that code for DA receptors, dopamine receptor d1 (Drd1a) and dopamine receptor d2 (Drd2). Increased expression of Drd1a has been observed in ethanol-dependent mice [31], while lower Drd1a expression was found in high-running strains of mice [32,33]. Over-expressing Drd2 reduced ethanol consumption in ethanol preferring rats [34,35], and high-alcohol preferring mice express striatal Drd2 at lower levels than low-alcohol preferring mice [36]. However, Drd2 expression was significantly less in high-running mice [33]. Brain derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), the final gene in which we were interested, was selected based on its general role in promoting cell survival and proliferation. Bdnf expression has been shown in several studies to be increased after exercise [20,37,38]. Furthermore, over-expression of Bdnf led to decreased ethanol consumption while Bdnf heterozygous knockouts had increased ethanol consumption [39]. Table 1 provides a summary of the expression patterns, functions, reasons for inclusion in the study, and references for these genes.

Table 1.

List of genes assayed for expression, and relevant details.

| Gene name | Translated protein | Brain expression | Function | Reason for inclusion | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th | Tyrosine hydroxylase | Midbrain (ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra), and Pons (locus coerulus) | Rate-limiting enzyme in production of dopamine, hydroxylizes tyrosine into L- DOPA | Implicated in exercise and ethanol behaviors | [24–25,46–47] |

| Slc18a2 | Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 | Midbrain (ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra, raphe nuclei) and Pons (locus coerulus) | Packaging of cytosolic dopamine into synaptic vesicles to facilitate release | SNPs associated with ethanol behavior, and with locomotor behavior. Knockout mice (+/−) drink more. | [27–30] |

| Slc6a3 | Dopamine active transporter | Midbrain (ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra) | Reuptake of dopamine from the synapse | SNPs associated with ethanol behavior | [26,29] |

| Drd1a | Dopamine receptor D1 | Striatum, cortex, olfactory tubercules, olfactory bulbs | G-protein coupled receptor - signaling cascade activates adenylyl cyclase | Implicated in exercise and ethanol behaviors | [31–33] |

| Drd2 | Dopamine receptor D2 | Midbrain, striatum, and cortex | G-protein coupled receptor - signaling cascade decreases adenylyl cyclase | Implicated in exercise and ethanol behaviors | [33–36,48] |

| Bdnf | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | Many regions, but highly expressed in hippocampus | Nerve growth factor important for cell survival and proliferation | Increased after exercise, may play role in exercise neuroprotection from binge ethanol consumption | [20,37–39,52] |

This study was designed with two aims. First we wanted to replicate the phenomenon of hedonic substitution, and second to investigate mesolimbic DA pathway gene expression plasticity in response to access to ethanol and wheel running that may account for some of the behavioral differences.

2. Methods

2.1 Statement on animal care

This study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado, Boulder (Boulder, Colorado) following guidelines established by the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. All possible measures were taken to minimize animal discomfort.

2.2 Animals

Animals were bred and housed at the Specific Pathogen Free facility, operated by the Institute for Behavioral Genetics at the University of Colorado, Boulder (Boulder, Colorado). Female C57BL/6J mice aged 60–90 days were used for these experiments. Animals were individually housed in polycarbonate cages (30.3 × 20.6 × 26 cm) on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM. Room temperature was maintained between 23 and 24.5°C. All mice had ad libitum access to standard chow (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, Indiana) and water. Animals were monitored daily and body weights were recorded every 4 days. Food was weighed every 4 days, on the same schedule as body weights.

2.3 Behavioral paradigm

Mice were tested using a previously established paradigm that lead to differences in ethanol consumption when given access to a free running wheel [11]. The four conditions (n=15/condition) included cages with 1) water only, 2) 1 bottle of water and 1 bottle of ethanol (two-bottle choice), 3) water and ethanol two-bottle choice with a running wheel, and 4) water only with a running wheel. The protocol lasted 16 days. Mice housed with a running wheel (diameter 24.2cm, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Massachusetts) had 24-hour access to the wheel for all 16 days. Wheel revolutions were counted using a magnet and magnetic switch (Harvard Apparatus) and recorded daily. Mice housed with ethanol two-bottle choice progressed as follows: water only for days 1–3, 3% ethanol (v/v) for days 4–5, 7% ethanol for days 6–7, and 10% ethanol for days 8–16 (Table 2). The side of the cage the bottles were on was alternated every two days. Individual consumption of water and ethanol (if applicable) were recorded daily. On day 16 during the second hour of the light cycle, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Groups of 5 mice were staggered to start the protocol every 2 days so as to minimize the variation in tissue collection times on day 16. Daily measurements of wheel revolutions (1 day each for 4 mice), water (1 day for 1 mouse) and ethanol consumption (1 day each for 4 mice) are missing due to sporadic equipment failure (i.e. switches detecting wheel magnets could be bumped out of alignment or fluid tubes could leak if stopper seal was not secured tight enough). These missing values were imputed as the average of the preceding and following days.

Table 2.

2×2 Behavioral paradigm for wheel running exposure and ethanol consumption

| Days 1–3 | Days 4–5 | Days 6–7 | Days 8–16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Running | Water only | 3% ethanol & water | 7% ethanol & water | 10% ethanol & water |

| Water only | ||||

| Sedentary | Water only | 3% ethanol & water | 7% ethanol & water | 10% ethanol & water |

| Water only | ||||

2.4 Saccharin control group

In addition, 10 mice were housed with two-bottle choice water and saccharin in two cage conditions (n=5/condition), either with or without wheel in cages described above. After water only for days 1–3, a 0.033% saccharin solution was added for days 4–16 [40,41]. This concentration was sufficient to produce approximately 95% preference in two-bottle choice. The side of the cage the bottles were on was alternated every two days and individual consumption of water and saccharin were recorded daily.

2.5 Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRTPCR)

Whole brains were removed and the midbrain, striatum, hippocampus, and cortex were dissected and stored in RNALater™ (Ambion, Foster City, California) at −20°C. Total RNA from dissected regions was extracted using EZNA Total RNA Kit II (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, Georgia). Quality and quantity of RNA were determined by gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop™spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). A260/A280 was determined to be excellent in each case (>1.8). Total mRNA was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). For real-time quantitative PCR, we used Taqman™ primers and probes (Applied Biosystems) for the following genes: Bdnf (Mm04230607_s1), Drd1a (Mm01353211_m1), Drd2 (Mm00438545_m1), Th (Mm00447557_m1), Slc6a3 (Mm00438388_m1), and Slc18a2 (Mm00553058_m1). Endogenous genes Gapdh (4352339E) and Actnb (4352341E) were used as controls. Real-time quantitative PCRs were performed using an ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems) running Sequence Detection Systems software (SDS v2.3, Applied Biosystems). All target genes were normalized using the 2−ΔΔCt method [42,43].

2.6 in situ hybridization (ISH)

Whole brains were removed and flash frozen in isopentane on dry ice and stored at −70°C. Brains were sectioned coronally into 14 micron slices using a cryostat (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), thaw mounted on poly-L-lysine coated glass slides (ThermoFisher Scientific) and stored at −70°C. We used a previously established method for in situ hybridization of radiolabeled antisense riboprobes [44]. Briefly, probes were transcribed in vitro with 35S-UTP (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts) as the sole source of UTP. Constructs for three genes, Drd1a, Bdnf, and Slc18a2 were cloned into pT3T7 transcription vectors, were acquired from ThermoFisher Scientific: Drd1a – EMM1032-613237 (600bp), Bdnf – EMM1032-607279 (800bp), Slc18a2 – EMM1032-591860 (1500bp). All vectors were linearized with EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts) and transcribed using T3 RNA polymerase (Promega, Fitchburg, Wisconsin). Constructs for other three genes, Th, Slc6a3, and Drd2 were cloned from cDNA used for the RT-PCR experiment. Primers (www.idtdna.com) were designed using Primer Blast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) software, and a T7 binding site was added to each reverse primer. Primer sequences were as follows: Th forward (GCCGTCTCAGAGCAGGATAC) and reverse (GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGACCAGGGAACCTTGTCCTCT); Slc6a3 forward (GAGGTTCAAGAGCGGGAGAC) and reverse (GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATCCACACCACCTTCCCTG); and Drd2 forward (CTTTGCAGACCACCACCAAC) and reverse (GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGGGTACAGTTGCCCTTGA). Twenty five PCR cycles were used to generate clones. Transcription was carried out using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). Hybridizations were performed within 1 day of transcription.

On the day of hybridization, after warming to room temperature, tissue was first fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (15min), rinsed with 1x phosphate buffered saline (3×5min), then rinsed with 0.1M TEA (2min). Next the tissue was acetylated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1M TEA (15min) and then dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions of 50%, 70%, 95%, 100% and 100% (3min each). Radiolabeled riboprobes were diluted in a hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 300mM NaCl, 10mM Tris, 1mM EDTA, and 1x Denhardt’s solution, and ~100μL were pipetted onto a 24mm × 60mm coverslip, then placed upside down covering tissue. Coverslips were sealed to slides using DPX mountant (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri). Tissue sections were hybridized with riboprobe solution for 16 hours at 60°C. After hybridization, tissue section slides were washed with 4x saline sodium citrate (SSC) before being treated with RNase A (20μg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C. Then tissue sections were desalted by incubation in graded SSC solutions (all with 1mM DTT) to a final stringency of 0.1xSSC at 65°C. Finally, sections were dehydrated with graded ethanol solutions, dried, and exposed to PhosphoScreens (Packard, Meriden, Connecticut) for at least 1 week. Slides for every mouse for each riboprobe were assayed at the same time to allow for direct comparisons between mice.

In order to relate the intensity of each screen image to a relative measure of tissue radioactivity, tissue standards containing known amounts of 35S were exposed along with tissue on each film. Tissue standards were prepared by mixing measured amounts of isotope with a homogenate prepared from whole brain. Actual concentrations of radioactivity were measured in weighted aliquots. The 35S standards contained from 0 to 25 nCi/mg. Ten standards were used for each isotope, and were used to construct standard curves relating optical density and a measure of radioactivity (counts per minute per mg).

Exposed PhosphoScreens were imaged with a Cyclone PhosphoImage reader (Packard), and image. tif files (600 dpi) were imported into the OptiQuant analysis suite (Packard). Slides were de-identified and brain regions of interest were circled as well as background. At least 3, and as many as 20 measurements were taken from each animal, and the values obtained were averaged for each animal.

2.7 Statistical analyses

A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to identify group differences in alcohol consumption (runners vs. non-runners). A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to identify group differences in daily wheel revolutions (drinkers vs. non-drinkers). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine group differences in body weight (2×2 drinkers vs. non-drinkers and runners vs. non-runners). For repeated measures ANOVAs, missing daily values were imputed from the average of the previous and following days’ values. A two-way ANOVA was used to determine group differences due to cage and fluid for food consumption data and for gene expression data (2×2, drinkers vs. non-drinkers and runners vs. non-runners). Average ΔCt values for each mouse were used for RT-PCR. Average CPM/mg values for each mouse were used for in situ hybridization data. Repeated measures ANOVAs were calculated using SPSS v20, two-way ANOVAs were calculated using R v2.15.2 (www.r-project.org).

3. Results

3.1 Mice

Body weights increased over the course of 16 days (F3,168=29.32, p<0.001) but there were no main effects of ethanol or running. There was a slight difference in the amount of food consumed, with significant main effects observed for both ethanol and a running wheel. Mice that had access to ethanol consumed less food than mice that only had access to water (3.52 ± 0.09 g/day vs. 3.85 ± 0.08 g/day, respectively; F1,56=8.393, p<0.01). Mice with access to a running wheel consumed more food than mice housed in empty cage (3.83 ± 0.09 g/day vs. 3.54 ± 0.08 g/day, respectively, F1,56=6.811, p<0.05).

3.2 Voluntary running and ethanol consumption

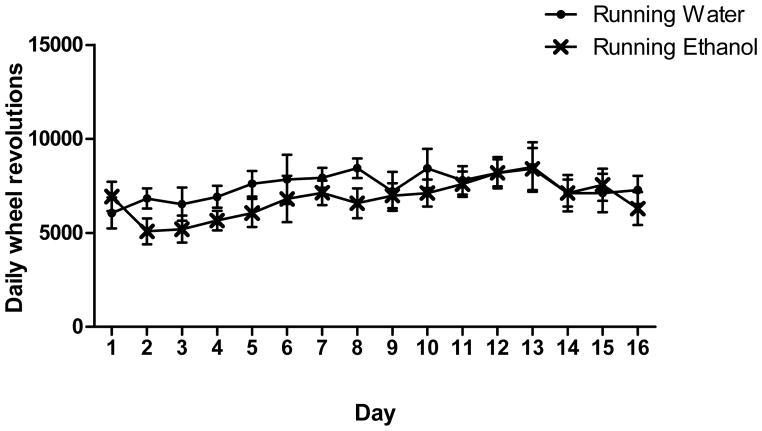

As expected, mice ran a considerable distance each day, averaging 7144 revolutions per day, equaling 5431 meters per day. There was a slight increase in daily revolutions over the course of 16 days (Figure 1, F15,420=2.8, p<0.001) There was no significant difference in number of revolutions between mice with access to water only and mice with access to ethanol.

Fig. 1.

Average daily running wheel revolutions for mice with water only and mice with two-bottle choice ethanol over 16 days. Average number of revolutions for water only mice (Circles, n= 15, 7486 ± 590 revolutions/day) and for ethanol-drinking mice (X’s, n= 15, 6798 ± 584 revolutions/day). Mean ± SEM are reported.

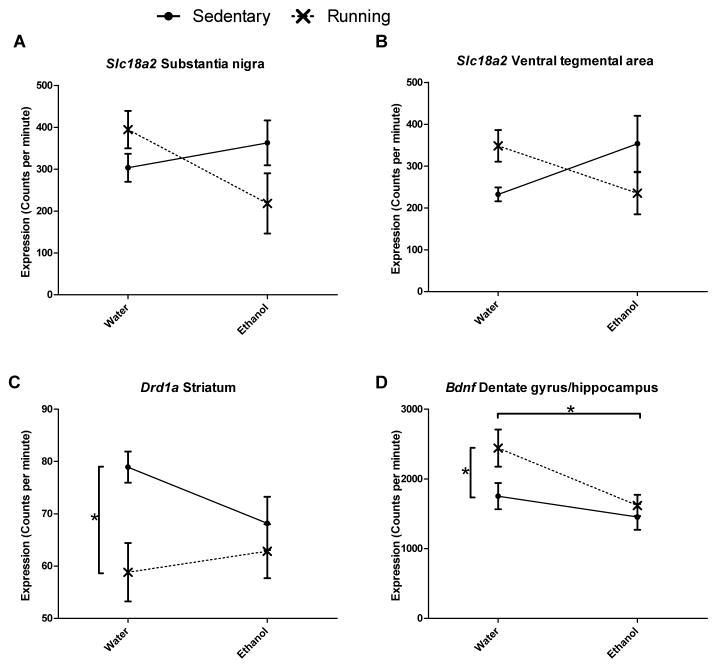

Mice with access to running wheel significantly consumed (g/kg; F1,28=11.6, p<0.01) and preferred (F1,28=30.7, p<0.001) less ethanol than mice housed in an empty cage over the course of 16 days (Figure 2a and 2b).

Fig. 2.

Average daily ethanol consumption for mice with empty cage (Circles) and mice with access to a running wheel (X’s) over 16 days. Ethanol consumption is shown as average amount of ethanol consumed per body weight (A) and as an ethanol preference ratio (B) defined as volume of ethanol fluid consumed divided by total fluid consumed. Ethanol concentrations (v/v) for each day are reported on the x-axis. Mean ± SEM are reported.

3.3 Saccharin control experiment

In the ten mice in the saccharin control experiment there was no significant change in body weight over the 16 days, nor was there any effect of access to a running wheel. Access to a running wheel did not significantly change saccharin consumption as measured by milligrams saccharin per kilogram body weight or as a saccharin preference ratio (data not shown).

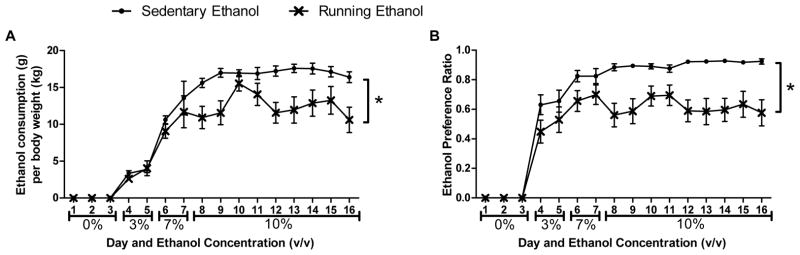

3.4 Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRTPCR)

There were no significant differences in gene expression between groups for Th, Drd2, and Slc6a3. In addition, there were no differences in gene expression for Drd1a when measured in the cortex. In the midbrain, there was a main effect of ethanol availability on expression of Slc18a2 (Figure 3a, F1,16=18.9, p<0.001), ethanol-consuming mice showing increased expression compared to the group that only had access to water. In the striatum, there was a main effect of ethanol availability on the expression of Drd1a (Figure 3b, F1,16=6.9, p<0.05), with ethanol-consuming mice showing decreased expression levels. In the hippocampus, there were significant main effects of running wheel availability (F1,17=6.3, p<0.05) and ethanol availability (F1,17=5.5, p<0.05) on Bdnf expression (Figure 3c). Running mice had increased expression of Bdnf, while ethanol-drinking mice had decreased expression.

Fig. 3.

Relative mRNA expression levels as measured by real-time quantitative PCR for (A) Slc18a2 (midbrain), (B) Drd1a (striatum), and (C) Bdnf (hippocampus). Main effects due to availability of ethanol were observed in midbrain Slc18a2, striatal Drd1a, and hippocampal Bdnf. Main effects due to availability of a running wheel were observed in hippocampal Bdnf. There were no significant interaction effects. Expression levels are shown as mean fold change ± SEM relative to sedentary/water only group for each gene. No significant differences were observed in other genes/regions.

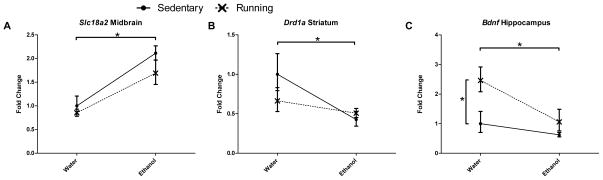

3.5 in situ hybridization (ISH)

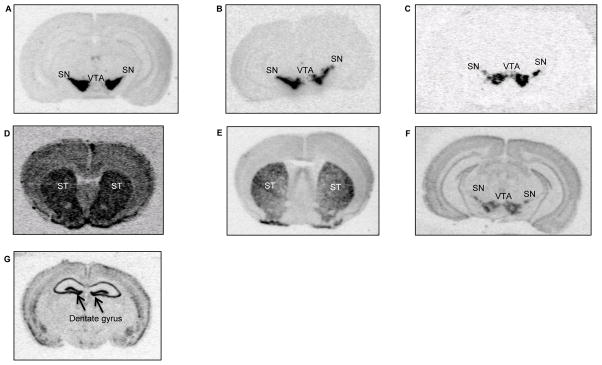

We measured gene expression using in situ hybridization (ISH) to confirm the results from qRTPCR. There were no differences in gene expression in examined regions between groups for Th, Drd2, and Slc6a3. There were differences in expression for midbrain Slc18a2 and striatal Drd1a when measured using ISH. Contrary to expression levels detected through qRTPCR, there was an ethanol x running wheel interaction effect on the expression of Slc18a2 in both midbrain sub-regions: the substantia nigra (F1,18=5.2, p<0.05) and the ventral tegmental area (F1,18=5.6, p<0.05, Figures 4a and 4b). The interaction effect was as follows: in empty cages, ethanol-drinking mice had increased expression of Slc18a2 compared to water-only mice, while in cages with running wheels; ethanol-drinking mice had decreased expression of Slc18a2. In the striatum, there was a main effect of running wheel availability on expression of Drd1a (Figure 4c). Mice with access to running wheels showed decreased expression Drd1a compared to mice without access (F1,20=7.0, p<0.05). There was no effect of availability of ethanol on Drd1a expression. In concordance with expression levels detected through qRTPCR, there were significant main effects of access to running wheel (F1,20=4.4, p<0.05) and access to ethanol (F1,20=7.7, p<0.05) on expression of Bdnf in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Figure 4d). Access to a running wheel increased expression, while access to ethanol decreased expression. There was no significant interaction effect. Representative images from each ISH assay are shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 4.

Results of in situ hybridization showing mRNA expression levels for Slc18a2 in midbrain subregions: (A) substantia nigra (SN) and (B) ventral tegmental area (VTA), Drd1a in (C) striatum (ST), and (D) Bdnf in hippocampus (HC). Significant interaction effects were observed in both midbrain regions for Slc18a2. Significant main effects due to availability of running wheel were observed in striatal Drd1a and in hippocampal Bdnf. A main effect due to availability of ethanol was observed in hippocampal Bdnf. Values shown (mean ± SEM) have been converted to counts per minute.

Fig. 5.

Representative images of each in situ hybridization assay. For Th (A), Slc6a3 (B), and Slc18a2 (C), both the substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) were quantified. For Drd1a (D), the whole striatum (ST) was quantified. For Drd2 (E and F), the ST (E), SN and VTA (F) were quantified. For Bdnf (G), the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus was quantified.

4. Discussion

4.1 Evidence for hedonic substitution

This study provides additional evidence for the behavioral interaction between voluntary exercise and ethanol consumption. Using a similar protocol as in Ehringer et al. (2009), we observed decreased ethanol consumption and preference in female C57Bl/6J mice than in their non-running counterparts [11]. Ehringer (2009) demonstrated that the substitution effect was due specifically to a running wheel, and not to a locked wheel, at least in females. Further, they went on to show that ethanol metabolism was unchanged due to running. The current study shows running on an exercise wheel failed to reduce consumption and preference for a saccharin solution, suggesting that the effects of exercise may not be sufficient to alter all rewarding behaviors.

Contrary to Ehringer et al. (2009), which studied hedonic substitution in both sexes, the current study only examined females. Although this limits the interpretation of the findings, female C57BL/6J mice run more and drink more than their male counterparts, and in this preliminary search for genes involved in hedonic substitution, it was important that the substitution effect was most robust, as is more consistently observed in females. Furthermore, while there may be concern about effects of the estrous cycle, it is likely that our sample size and the length of the study wash out any effects. Sixteen days encompasses 4–5 complete cycles, therefore any effects across our group of mice should only add random noise. Unfortunately, the invasive nature of monitoring the estrous cycle [45] would have fundamentally, and adversely, affected the behavioral paradigm.

4.2 Transcriptional changes in mesolimbic reward pathway

In addition to providing evidence for the behavioral interaction, this study attempted to elucidate the underlying molecular basis for hedonic substitution, utilizing measures of gene expression. Although exercise has been and is currently being used as a behavioral intervention for alcohol use disorders, a more thorough understanding of the mechanisms involved could provide a framework for more effective interventions. The implication of the mesolimbic DA pathway in the regulation of voluntary exercise and ethanol consumption provided a foundation for hypothesizing which genes could play a role. We selected genes based on their role in modulating this pathway, in addition to prior implications in exercise and ethanol behaviors.

We examined the expression of six genes, all actors in the mesolimbic DA pathway, first by quantitative real-time PCR, then by in situ hybridization (ISH). In the midbrain we were unable to detect changes in expression of Th, Drd2, and Slc6a3. Although several groups have shown an increase in Th in response to exercise and ethanol, protocol and organism differences may explain the discrepancy in findings. Greenwood (2011) saw differences in the caudal third of the VTA of male Fischer 344 rats after 6 weeks of running, with no differences in the mid and rostral portion, and no differences reported for SN [24]. Thus, in this case there are several possible explanations for differences with our study. First, sex differences are often seen in behavioral paradigms and that study included only males, while ours focused on females. Second, Greenwood studied rats, whereas we are tested mice. Third, in the context of the larger rat brain, it is easier to dissect out specific regions as was performed to distinguish between caudal, mid, and rostral sections of the VTA. In addition, and supporting our finding, Nascimento et al. (2011) did not see an increase in Th expression in the VTA of rats after 8 weeks of running compared to untrained control rats [46]. Other in vitro studies observed increases in Th in response to acute ethanol administration [25,47], but our protocol is a voluntary unlimited continuous access, which is quite different than acute exposure.

With regard to Drd2, the lack of differences observed in our study is not entirely inconsistent with previous papers that have implicated a role of this gene in both alcohol and exercise. Polymorphisms in Drd2, as well as changes in expression have been implicated in both behaviors. Specifically, polymorphisms in the human gene DRD2 have been associated with alcohol dependence [48]. Striatal Drd2 expression has been shown to be less in high running mice [33] or the same in different strains of mice shown to differ in baseline running [32]. However, overexpression of Drd2 has been associated with decreased ethanol consumption in rats [34,35]. Similarly, high alcohol preferring mice express less Drd2 than low alcohol preferring mice [36]. It seemed plausible that running may induce Drd2 expression, thereby decreasing ethanol consumption, although our results do not support this hypothesis. Additional studies are needed to clarify possible regional brain differences and/or temporal effects than may account for the inconclusive findings.

Our failure to find differences in Slc6a3 is somewhat consistent with previous reports showing knockout mice have similar ethanol consumption, at least in females, as their wild-type controls [29]. However, polymorphisms in SLC6A3 have been associated with alcohol use disorders in humans [26], so there was justification to examine it. To our knowledge, this gene has not been investigated in the context of exercise. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the expression of Slc6a3 affects voluntary ethanol or exercise behavior; one possibility is that any effects it exerts may be mediated through a different region of the brain.

In the midbrain, mRNA expression measured using qRTPCR assays of Slc18a2 appeared to increase in response to consumption of ethanol. However, when looking at more fine-grained patterns in the VTA or SN using the in situ technique, the main effect of ethanol was abolished, and we observed an interaction effect. In the absence of a running wheel, ethanol led to increased expression; while in running mice, ethanol led to decreased expression. Other midbrain regions expressing Slc18a2, such as the raphe nuclei in the caudal midbrain, may account for some of these differences, and highlight the importance of more targeted regional selections. The interaction effect observed in the VTA and SN is particularly interesting, and we speculate that in the absence of running, there could be increased DA release due to ethanol, which facilitates the need for higher expression of Slc18a2. This could be tested in future studies. Two studies have associated polymorphisms in the human gene SLC18A2 with alcohol use disorders [27,28], and two studies have examined ethanol behavior with Slc18a2 knockout mice [29,30]. In female mice, the two studies show conflicting results, with the effect of heterozygous deletion of Slc18a2 having no effect [29] or decreasing ethanol preference [30]. Our study adds support to the idea that expression levels of Slc18a2, not just polymorphisms, are important for ethanol-related behaviors.

In the striatum, expression of Drd1a showed different patterns of response dependent on the method of detection. In the qRTPCR experiments, Drd1a showed decreased expression in response to ethanol, while this decrease was observed in the wheel running condition for in situ assays. The mice in this study were voluntarily drinking ethanol, and therefore not ethanol-dependent, however Contet et al. (2011) observed increased Drd1a expression in ethanol-dependent mice [31]. Our observation of reduced expression measured by ISH is consistent with work by Knab et al. (2009), who observed lower baseline Drd1a expression in a high-running strain of mice compared to a low-running strain [32]. Thus, there remains a high interest in this gene for its role in these two behaviors, but further studies should address specificity of alcohol exposure, possible temporal effects, and other brain regions.

Our data, consistent using both qRTPCR and ISH, show that 16 days of voluntary exercise increases hippocampal Bdnf expression and 16 days of voluntary ethanol consumption decreases expression, which suggests changes in neuronal structure and neurogenesis. The hippocampus provides contextual information to the striatum based on prior associated experiences [3]. In one of the few studies examining the influence of exercise on ethanol behaviors, Leasure and Nixon (2009) demonstrated exercise’s ability to protect hippocampal cells from the effects of binge ethanol consumption [49]. These findings complement other work showing the ability of exercise to initiate neurogenesis in the hippocampus [50,51], as well as other studies showing that changes in Bdnf expression result in changes in ethanol behaviors [reviews 39,52]. Alterations in the hippocampus due to exercise may influence the signaling between the striatum and hippocampus, affecting the reward response to ethanol drinking.

Conclusions

These data reaffirm the hedonic substitution narrative, and make the first attempt at identifying the underlying genetic changes that occur to influence this interaction. Of the genes in which differences were observed, Slc18a2 expression in the VTA and SN responds differently to ethanol depending on the presence or absence of a running wheel, and Bdnf expression in the hippocampus changes in response to both running and ethanol. Drd1a in the striatum may also be responsive to both running and ethanol. This suggests that multiple genes and brain regions are important in regulating hedonic substitution, and supports the idea that the mesolimbic DA pathway plays an important role. Future studies should focus on global gene expression to identify other genes as well as assessing whether observed mRNA changes correspond to similar protein changes. It will also be useful to expand this behavioral model to include testing whether running produces similar effects on voluntary consumption of other drugs of abuse.

Highlights.

16 days of wheel running decreased ethanol consumption, with no effect on saccharin consumption.

Changes in expression of midbrain Slc18a2 due to ethanol were dependent on running.

Running and ethanol consumption had opposing effects on hippocampal Bdnf expression.

Striatal expression of Drd1a was depressed by both running and ethanol.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Rebecca Rodman, Lymaris Quinones-Davila, and Jason Segall for help with tissue preparation. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 DA017637 (TMD) and R01 AA017889 (MAE, salary support).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.WHO | World Health Organization. www.who.int.

- 2.Foroud T, Li TK. Genetics of alcoholism: a review of recent studies in human and animal models. Am J Addict. 1999;8:261–78. doi: 10.1080/105504999305677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris RA, Trudell JR, Mihic SJ. Ethanol’s molecular targets. Sci Signal. 2008;1:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.128re7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMillan DE. Effects of access to a running wheel on ethanol intake in rats under schedule-induced polydipsia. Curr Alcohol. 1978;3:221–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMillan DE, McClure GY, Hardwick WC. Effects of access to a running wheel on food, water and ethanol intake in rats bred to accept ethanol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werme M, Lindholm S, Thorén P, Franck J, Brené S. Running increases ethanol preference. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:301–8. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozburn AR, Harris RA, Blednov Ya. Wheel running, voluntary ethanol consumption, and hedonic substitution. Alcohol. 2008;42:417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammer SB, Ruby CL, Brager AJ, Prosser RA, Glass JD. Environmental modulation of alcohol intake in hamsters: effects of wheel running and constant light exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1651–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehringer MA, Hoft NR, Zunhammer M. Reduced alcohol consumption in mice with access to a running wheel. Alcohol. 2009;43:443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstock J. A review of exercise as intervention for sedentary hazardous drinking college students: rationale and issues. J Am Coll Health. 2010;58:539–44. doi: 10.1080/07448481003686034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy TJ, Pagano RR, Marlatt Ga. Lifestyle modification with heavy alcohol drinkers: effects of aerobic exercise and meditation. Addict Behav. 1986;11:175–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correia CJ, Benson Ta, Carey KB. Decreased substance use following increases in alternative behaviors: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2005;30:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werch CE, Bian H, Carlson JM, Moore MJ, Diclemente CC, Huang I-C, et al. Brief integrative multiple behavior intervention effects and mediators for adolescents. J Behav Med. 2011;34:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith Ma, Lynch WJ. Exercise as a potential treatment for drug abuse: evidence from preclinical studies. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:82. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanarek RB, Marks-Kaufman R, D’Anci KE, Przypek J. Exercise attenuates oral intake of amphetamine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:725–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00022-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ussher M, Nunziata P, Cropley M, West R. Effect of a short bout of exercise on tobacco withdrawal symptoms and desire to smoke. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:66–72. doi: 10.1007/s002130100846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith Ma, Walker KL, Cole KT, Lang KC. The effects of aerobic exercise on cocaine self-administration in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:357–69. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2321-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dishman RK, Berthoud H-R, Booth FW, Cotman CW, Edgerton VR, Fleshner MR, et al. Neurobiology of exercise. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:345–56. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Preferential stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens by opiates, alcohol, and barbiturates: studies with transcerebral dialysis in freely moving rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;473:367–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb23629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5274–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Ethanol preferentially stimulates dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;115:131–2. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenwood BN, Foley TE, Le TV, Strong PV, Loughridge AB, Day HEW, et al. Long-term voluntary wheel running is rewarding and produces plasticity in the mesolimbic reward pathway. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217:354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He D-Y, Ron D. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor reverses ethanol-mediated increases in tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity via altering the activity of heat shock protein 90. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12811–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706216200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Zwaluw CS, Engels RCME, Buitelaar J, Verkes RJ, Franke B, Scholte RHJ. Polymorphisms in the dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3/DAT1) and alcohol dependence in humans: a systematic review. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:853–66. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Z, Walther D, Yu X-Y, Li S, Drgon T, Uhl GR. SLC18A2 promoter haplotypes and identification of a novel protective factor against alcoholism. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1393–404. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwab SG, Franke PE, Hoefgen B, Guttenthaler V, Lichtermann D, Trixler M, et al. Association of DNA polymorphisms in the synaptic vesicular amine transporter gene (SLC18A2) with alcohol and nicotine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2263–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall FS, Sora I, Uhl GR. Sex-dependent modulation of ethanol consumption in vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) and dopamine transporter (DAT) knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:620–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savelieva KV, Caudle WM, Miller GW. Altered ethanol-associated behaviors in vesicular monoamine transporter heterozygote knockout mice. Alcohol. 2006;40:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contet C, Gardon O, Filliol D, Becker JAJ, Koob GF, Kieffer BL. Identification of genes regulated in the mouse extended amygdala by excessive ethanol drinking associated with dependence. Addict Biol. 2011;16:615–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knab AM, Bowen RS, Hamilton AT, Gulledge Aa, Lightfoot JT. Altered dopaminergic profiles: implications for the regulation of voluntary physical activity. Behav Brain Res. 2009;204:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathes WF, Nehrenberg DL, Gordon R, Hua K, Garland T, Pomp D. Dopaminergic dysregulation in mice selectively bred for excessive exercise or obesity. Behav Brain Res. 2010;210:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanos PK, Taintor NB, Rivera SN, Umegaki H, Ikari H, Roth G, et al. DRD2 Gene Transfer Into the Nucleus Accumbens Core of the Alcohol Preferring and Nonpreferring Rats Attenuates Alcohol Drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:720–8. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000125270.30501.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thanos PK, Volkow ND, Freimuth P, Umegaki H, Ikari H, Roth G, et al. Overexpression of dopamine D2 receptors reduces alcohol self-administration. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1094–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bice PJ, Liang T, Zhang L, Strother WN, Carr LG. Drd2 expression in the high alcohol-preferring and low alcohol-preferring mice. Mamm Genome. 2008;19:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Praag H. Neurogenesis and exercise: past and future directions. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10:128–40. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neeper SA, Gómez-Pinilla F, Choi J, Cotman C. Exercise and brain neurotrophins. Nature. 1995;373:109. doi: 10.1038/373109a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghitza UE, Zhai H, Wu P, Airavaara M, Shaham Y, Lu L. Role of BDNF and GDNF in drug reward and relapse: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:613–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamens HM, Burkhart-Kasch S, McKinnon CS, Li N, Reed C, Phillips TJ. Sensitivity to psychostimulants in mice bred for high and low stimulation to methamphetamine. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:110–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marks MJ, Pauly JR, Gross SD, Deneris ES, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Heinemann SF, et al. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit RNA after chronic nicotine treatment. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2765–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldman JM, Murr AS, Cooper RL. The rodent estrous cycle: characterization of vaginal cytology and its utility in toxicological studies. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2007;80:84–97. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nascimento PSDo, Lovatel Ga, Barbosa S, Ilha J, Centenaro La, Malysz T, et al. Treadmill training improves motor skills and increases tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra pars compacta in diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2011;1382:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gayer GG, Gordon A, Miles MF. Ethanol increases tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dick DM, Wang JC, Plunkett J, Aliev F, Hinrichs A, Bertelsen S, et al. Family-based association analyses of alcohol dependence phenotypes across DRD2 and neighboring gene ANKK1. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1645–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leasure JL, Nixon K. Exercise neuroprotection in a rat model of binge alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:404–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark PJ, Kohman Ra, Miller DS, Bhattacharya TK, Brzezinska WJ, Rhodes JS. Genetic influences on exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis across 12 divergent mouse strains. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:345–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clark PJ, Kohman Ra, Miller DS, Bhattacharya TK, Haferkamp EH, Rhodes JS. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and c-Fos induction during escalation of voluntary wheel running in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2010;213:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis MI. Ethanol-BDNF interactions: still more questions than answers. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:36–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]