Biomaterials play a central role in many areas of medicine, including drug delivery, tissue regeneration and implantable devices.[1–10] For some applications, biodegradable elastomeric materials have particular utility, since their compliance under force resembles more closely the elastic nature of many human tissues.[11–13] These materials have been utilized in various fields of tissue engineering, such as bone formation, nerve regeneration, vascular repair, wound healing, treatment of retinal degeneration and myocardial repair.[14–20] Despite their broad potential utility, different applications require elastomers with specifically tuned mechanical, biological, and degradation profiles to match the target tissue requirements. Here we describe the development of a family of biodegradable poly(ester amide) elastomers that are demonstrated to possess excellent elasticity under hydrated conditions, and are biocompatible and degradable in vivo. Analysis of the chemical/physical properties of these materials also provides insight into the structure/function relationships of biomaterials, particularly how molecular structures affect mechanical properties and biocompatibility.

Poly(glycerol-sebacate) (PGS) and its analog, poly(xylitol-sebacate) (PXS) are polyester elastomers that have been shown to be biocompatible in vivo.[11, 21] PGS is elastic in both dehydrated and hydrated conditions, having a relatively low modulus and rapid in vivo degradation kinetics.[11] Further crosslinking between hydroxyl and carboxyl groups leads to elastomers with a higher modulus and a slower degradation rate, but at the expense of reduced elasticity. PXS has a similar ultimate tensile strain as PGS, but a higher Young’s modulus.[21] PXS loses a significant portion of its elasticity in aqueous environments. This is likely due to increased solvation of the abundant hydroxyl groups and extended chain conformations. We hypothesized that stronger elastomers could be generated by replacing some of the chemical crosslinks with physical interactions among polymer chains. Poly(ester amide)s are known to have strong mechanical properties due to hydrogen bonds between N-H···O=C.[22–24] However, amides can also form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which may affect the elasticity of materials in hydrated conditions. For these reasons, we hypothesized that (1) the incorporation of diamines with hydrophobic internal structures into the polyester chains could improve the mechanical properties of polyester elastomers, and (2) that such modification would enable elastomers to maintain their elasticity in aqueous environments due to less exposure of amides to water. A number of diamine monomers were selected for this study: 1,2-diamino-2-hydroxy-propane (DHP) contains a hydrophilic hydroxyl group between two primary amine groups; 1,4-Bis(3-aminopropyl)piperazine (BAP) has both hydrophobic structures and two ionizable tertiary amines; ethylenediamine (2C), hexamethylenediamine (6C) and 1,12-Diaminododecane (12C) share similar structures but with different numbers of hydrophobic methylene -CH2- units; 1,5-Diamino-2-methylpentane (DMP) possesses a methyl group in addition to the linear -CH2- groups.

The poly(ester amide) pre-polymers can be synthesized through simple polycondensation (Scheme 1). Diamine monomers were mixed with sebacic acid/glycerol or sebacic acid/xylitol at different molar ratios to synthesize modified PGS pre-polymers or to prepare PXS derivatives. PGS modified with DHP at a DHP/glycerol/sebacic acid molar ratio 2:1:3 was previously investigated.[25] The high percentage of amide bonds offers the elastomer a slow degradation rate in vivo. The crosslinked material is crystal-like in appearance when dehydrated, and elastomeric after hydration. In this study, we used a DHP/glycerol/sebacic acid molar ratio of 3:7:10 in order to reduce the interaction of excess amide bonds. This specific ratio was selected after comparing materials at DHP/glycerol/sebacic acid molar ratios 2:1:3, 3:7:10 and 1:9:10. This modification generated a typical rubber-like elastomer, poly(glycerol-sebacate-co-DHP) (PGSDHP 30%). PGS modified with BAP and DMP were also synthesized at the same ratio for comparison. Attempts to synthesize PGS-2C, 6C and 12C 30% at 140 °C were unsuccessful because of the solidification of the melted reaction systems within 12 h. Instead, PGS polymers containing 2C, 6C and 12C at a molar ratio of 10% were developed. One potential design advantage of PXS is that its degradation profile and mechanical strength can be controlled by the feeding ratio of sebacic acid/xylitol during synthesis.[21] Sebacic acid/xylitol at ratios of 1:1 and 6:5 were used in this study. The rationale behind the selection of molar ratio 6:5 was to reduce the degradation rate of PXS (1:1) without significantly reducing its elasticity.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic scheme for poly(ester amide)s. Diamine X is incorporated in the polymer bone via amide bonds. R can be H or polymer segments linked through ester bond.

The poly(ester amide)s (Table 1), PGS and PXS pre-polymers were characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The intense C=O stretches around 1734 cm−1 in the spectra confirm the formation of ester bonds for all polymers. The hydrogen bonded OH stretches of hydroxyl groups appear as a broad band at 3400 cm−1. All poly(ester amide) pre-polymers show bands around 1640 cm−1 and 1540 cm−1, which are amide I and amide II bands respectively, confirming the formation of amide bonds for all the poly(ester amide)s. The peaks around 1710 cm−1 for PXS1.2 (sebacic acid/xylitol molar ratio 6:5) and its derivatives are from the C=O stretches of unreacted carboxyl groups. In addition, 1H NMR spectroscopy was employed to characterize the pre-polymers. The area ratios of two peaks, -CO(CH2)7CH2CONH- and -CO(CH2)7CH2COO- confirm that the composition of diamines in the final pre-polymers were approximately the same as in the initial feed ratio of monomers. Elastomers were made by crosslinking pre-polymers in a vacuum oven under 15 mTorr at temperatures ranging from 120–135 °C. For example, PGS was crosslinked at 120 °C while PGS modified with 10% 12C (PGS-12C 10%) was cured at 135 °C due to its high viscosity at 120 °C. The curing time was 2 days except for PGS and PXS1.2-12C 10%, which were kept in the oven for 24 h. All of the crosslinked poly(ester amide)s were transparent and light yellow in color.

Table 1.

Physical properties of poly(ester amide) pre-polymers and elastomers[a].

| Polymer | Mn | PDI | Tg | Polymer density ρ [g/m3]x10−6 | Crosslink density [mol/m3] | Mc [g/mol] | Swelling Ratio(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGSDHP 30% | 3700 | 1.25 | −13°C | 1.09±0.05 | 286.1±28.5 | 3842.5±336.3 | 10.1±1.5 |

| PGSBAP 30% | 2780 | 2.5 | −8°C | 1.11±0.05 | 129.8±7.1 | 8535.7±361.3 | 14.9±3.7 |

| PGSDMP 30% | 5060 | 1.77 | −24°C | 1.14±0.05 | 162.7±11.8 | 7008.6±252.3 | 7.8±1.2 |

| PGSDMP 10% | 7250 | 2.1 | −31°C | 1.10±0.03 | 192.8±11.4 | 5712.9±247.2 | 3.6±1.1 |

| PGS-2C 10% | 3850 | 2.99 | −21°C | 1.12±0.03 | 367.2±44.7 | 3079.2±318.8 | 4.0±0.8 |

| PGS-6C 10% | 7220 | 2.1 | −28°C | 1.15±0.02 | 648.2±76.9 | 1791.5±196.2 | 6.2±1.1 |

| PGS-12C 10% | 9670 | 1.59 | −11°C | 1.16±0.02 | 1585.3±30.1 | 735.2±23.2 | 4.5±0.9 |

| PXS1.2DMP 30% | 3190 | 2.36 | −9°C | 1.16±0.02 | 315.2±19.7 | 3700.5±197.3 | 8.6±0.9 |

| PXS1.2-12C 10% | 2210 | 1.28 | −1°C | 1.18±0.03 | 1183.9±73.1 | 1000.7±55.3 | 11.9±1.6 |

Mn: number average molecular weight; PDI: polydispersity index; Tg: glass transition temperature; Mc: the molecular weight between crosslinks. The Mn and PDI are detected from pre-polymers and the rest of the parameters are for elastomers.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements revealed a glass transition temperature (Tg) lower than 0 °C for each crosslinked poly(ester amide) (Table 1), indicating that all the poly(ester amide) elastomers studied here are completely amorphous at room temperature or physiological temperatures. Representative tensile stress-strain curves of PGSDHP 30%, PGSDMP 30% and PGS-12C 10% at both hydrated and dehydrated states are shown in Fig. 1A–C. Although dehydrated PGSDHP 30% and PGS-12C 10% have similar ultimate tensile stress (σ) of ~10 MPa, the two elastomers experience different processes during extension as illustrated by the shape of the curves (Fig 1A and C). The sharp rise in the slope of PGSDHP 30% after 200% elongation is expected to be associated with the crystallization induced by stretching, a signature phenomenon of natural rubber during extension.[26] PBS-hydrated PGSDHP 30% lost most of its strength and elasticity in the dehydrated state while PGS-12C 10% maintained its properties after hydration. Despite having a similar shape to their stress-strain curves, PGSDMP 30% and PGS-12C 10% have a remarkable difference in strength (Fig. 1B and C). Three parameters: Young’s modulus (E), ultimate tensile strain (ε) and stress (σ) were measured to evaluate the mechanical properties of the elastomers (Fig. 1D–F). These results demonstrate that polyester elastomers modified with hydrophobic diamines have improved mechanical strength and elasticity under hydrated conditions. The mechanical strength was found to increase as the number of methylene groups in diamines with linear structures increases. DMP and 6C contain the same number of carbons. However, PGS-6C 10% was found to have a higher E, ε and σ than PGSDMP 10%. This can be explained by the existence of the methyl group, which may prevent the interaction between neighboring -CONHCH2CH(CH3)CH2CH2CH2NHCO- in PGSDMP. When the DMP modification was increased to 30%, the PGS derivative became a potentially valuable biomaterial because of its superior elasticity and E close to that of soft tissues.[27] Although 10% 12C is effective in reinforcing the E, ε and σ of PXS1.2, PXS1.2 modified with 30% DMP only shows an improvement in elasticity. Statistical analysis of the improvement in elasticity by diamine modifications is provided in the supporting information.

Figure 1.

Mechanical properties of poly(ester amide) elastomers. Representative stress-strain curves of dehydrated and hydrated PGSDHP 30% A), PGSDMP 30% B), PGS-12C10% C). Summary of poly(ester amide) elastomers D) Young’s modulus, E) ultimate tensile strain and F) ultimate tensile stress.

The crosslinking density, n and molecular weight between crosslinks, Mc (Table 1) were calculated according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature and ρ is the density.[26] Eq. (1) is derived by assuming that the internal energy stays constant under length variation and that the polymers are freely jointed chains.[26] Therefore, the n calculated here should be considered as the combined density of the chemical and effective physical crosslinks, noting that the effective physical crosslinks here are not real connections and are different from the strong physical crosslinks in thermoplastic elastomers.

Swelling ratio is an important parameter in the evaluation of biomaterials as most biomedical applications require materials with a low swelling ratio upon hydration. The ratio was calculated by the volume change after hydration in saline over the volume of dehydrated elastomers. All of the poly(ester amide) elastomers were found to have a low swelling ratio after hydration with the highest value around 15% (Table 1). Overall, PGS-modified with hydrophilic diamines swelled more than hydrophobic diamine modified PGS; PGS based elastomers showed less swelling than PXS derivatives, suggesting a direct relationship between polymer hydrophilicity and swelling.

Following polymer characterization and screening, four of the poly(ester amide) elastomers, PGSDMP 30%, PGS-12C 10%, PXS1.2DMP 30% and PXS1.2-12C 10% were selected for further studies because of their excellent mechanical properties, particularly the elasticity under hydrated conditions which renders the materials useful for many tissue engineering applications.

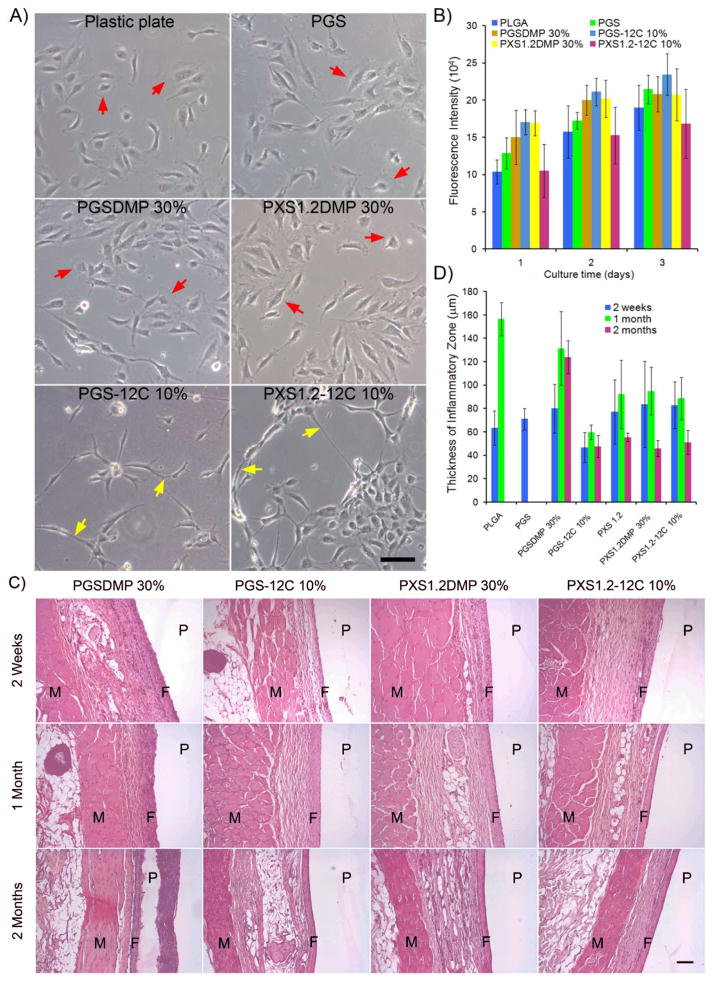

The in vitro degradation of poly(ester amide) elastomers was examined by placing elastomer slabs in PBS at 37 °C. After 90 days, PGSDMP 30%, PGS-12C 10%, PXS1.2DMP 30% and PXS1.2-12C 10% exhibited 37.9±1.3%, 12.8%±0.6%, 14.0±0.1% and 5.5±0.2% dry mass loss, respectively. To assess the in vitro biocompatibility of the polymers, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured on the elastomeric materials. Cells growing on PGSDMP 30% and PXS1.2DMP 30% had large lamellipodia (marked by red arrows in Fig. 2A), a morphology similar to that of cells on PGS, PXS1.2 and plastic cell culture treated plates. In contrast, cells cultured on PGS-12C 10% and PXS1.2-12C 10% had long cell protrusions and a tendency to connect together along the long axis of the cell body (marked by yellow arrows in Fig 2A), resembling some aspects of the tubular like structures that HUVECs form on Matrigel.[28] These variations in morphology are likely due to the difference in the chemical structure of the elastomers not the rigidity of substrates as the E of PXS1.2-12C 10% is in between those of PGS and plastic. The observed cellular morphological differences gradually disappeared as the confluency of cells increased. The cytotoxicity of the different elastomers was assessed by AlamarBlue assays. No significant differences in viability and proliferation rates (calculated p-values are listed in the supporting information) were observed between HUVECs cultured on poly(ester amide) elastomers and HUVECs cultured on PGS or poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

In vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of poly(ester amide) elastomers. A) Phase-contrast images of HUVECs after 24 h of growth on elastomeric materials. Lamellipodia are marked by red arrows, while long cell protrusions are highlighted by yellow arrows. The scale bar represents 100 μm. B) An AlamarBlue assay was used to quantify the viability and proliferation of cells on different materials. Fluorescence intensity is proportional to the number of cells. PLGA and PGS served as controls. C) Representative images of H&E stained sections of subcutaneously implanted materials with surrounding tissues. Samples were harvested at 2 weeks, 1 month and 2 months following implantation. The regions of skin muscles, fibrous inflammatory zone and polymers are indicated by M, F, and P, respectively. The scale bar is 100 μm. D) Quantification of the in vivo biocompatibility by measurement of capsule thickness surrounding each implant. The thickness of the original fat tissue in between the dense inflammatory zone and skin muscle is not included.

To evaluate the in vivo biocompatibility, elastomer and PLGA discs were implanted subcutaneously onto the backs of Lewis rats (n=3 per sample, per timepoint). Animals were sacrificed at 2 weeks, 1 month and 2 months. Explants were processed for histology and stained with hematoxylin and eosine (H&E) (Fig. 2C). The thickness of the dense inflammatory zone was measured (Fig. 2D) and used together with the histological staining images as the assessments of biocompatibility. PGSDMP 30% was found to cause slightly higher inflammation than PLGA, while the biocompatibility of PGS-12C 10%, PXS1.2DMP 30% and PXS1.2-12C 10% is equivalent to or better than that of PLGA. Although some diamines are considered cytotoxic, most of the poly(ester amide) elastomers studied here showed no difference in biocompatibility when compared to unmodified polyester elastomers. One possible explanation for this, further supported by other poly(ester amide) polymer degradation experiments, is that the elastomers degraded mainly via hydrolysis of ester bonds, while the amide bonds remained stable.[22] PGS completely degraded within a month following implantation while PLGA degraded within 1–2 months. After 2 months, the PGSDMP 30%, PGS-12C 10%, PXS1.2DMP 30% and PXS1.2-12C 10% discs had degraded in diameter from 6.2 mm to 5 mm, 5.9 mm, 5.8 mm, and 6 mm respectively.

In conclusion, through the rational design of polymer structures, we have synthesized a novel family of poly(ester amide) elastomers with superior elasticity under hydrated conditions compared to unmodified polyester elastomers, excellent in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility and slow in vivo degradation rates. The elastomers reported here may be good candidates for the fabrication of nerve guidance conduits and other tissue engineering applications that require a slowly degrading, highly elastic scaffold. Our study also shed light on the structure-property relationship behind designing biodegradable elastomeric materials, providing valuable insights for the creation of new biomaterials. We expect that the incorporation of enzymatically degradable natural components such as β sheet forming peptides in polymer chains can also increase the elasticity and strength of polyester elastomers, while not significantly reducing their in vivo degradation rate.

Experimental

The detailed experimental procedures are available in the supporting information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine award number W81XWH-08-2-0034. The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office. The content of the manuscript does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The authors thank the helpful discussion with Christopher J. Bettinger, George C. Engelmayr, Jr., William L. Neeley, Jeffery M. Karp and Arturo J. Vegas.

Contributor Information

Dr. Hao Cheng, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA). Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

Dr. Paulina S. Hill, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

Dr. Daniel J. Siegwart, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

Nathaniel Vacanti, Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA).

Dr. Abigail K. R. Lytton-Jean, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

Prof. Seung-Woo Cho, Department of Biotechnology, Yonsei University, Seoul 120-749 (Korea)

Anne Ye, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA).

Prof. Robert Langer, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA). Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA). Division of Health Science Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

Prof. Daniel G. Anderson, Email: dgander@mit.edu, David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA). Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA). Division of Health Science Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

References

- 1.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Science. 1993;260:920. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Adv Mater. 2006;18:1345. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shea LD, Smiley E, Bonadio J, Mooney DJ. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:551. doi: 10.1038/9853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tirrell M, Kokkoli E, Biesalski M. Surf Sci. 2002;500:61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah RN, Shah NA, Lim MMD, Hsieh C, Nuber G, Stupp SI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906501107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson DG, Levenberg S, Langer R. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:863. doi: 10.1038/nbt981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Nature. 2004;428:487. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khademhosseini A, Langer R, Borenstein J, Vacanti JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507681102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman GH, Diaz F, Jakuba C, Calabro T, Horan RL, Chen JS, Lu H, Richmond J, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2003;24:401. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YD, Ameer GA, Sheppard BJ, Langer R. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:602. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serrano MC, Chung EJ, Ameer GA. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:192. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amsden B. Soft Matter. 2007;3:1335. doi: 10.1039/b707472g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Zou B, Shi ZY, Wu Q, Chen GQ. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3063. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panseri S, Cunha C, Lowery J, Del Carro U, Taraballi F, Amadio S, Vescovi A, Gelain F. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runge MB, Dadsetan M, Baltrusaitis J, Knight AM, Ruesink T, Lazcano EA, Lu L, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5916. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Webb AR, Ameer GA. Adv Mater. 2004;16:511. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahdavi A, Ferreira L, Sundback C, Nichol JW, Chan EP, Carter DJD, Bettinger CJ, Patanavanich S, Chignozha L, Ben-Joseph E, Galakatos A, Pryor H, Pomerantseva I, Masiakos PT, Faquin W, Zumbuehl A, Hong S, Borenstein J, Vacanti J, Langer R, Karp JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712117105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neeley WL, Redenti S, Klassen H, Tao S, Desai T, Young MJ, Langer R. Biomaterials. 2008;29:418. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelmayr GC, Cheng MY, Bettinger CJ, Borenstein JT, Langer R, Freed LE. Nat Mater. 2008;7:1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruggeman JP, Bettinger CJ, Nijst CLE, Kohane DS, Langer R. Adv Mater. 2008;20:1922. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrows TH, Gibson SJ, Johnson JD. Trans Soc Biomater. 1984:210. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsarava R, Beridze V, Arabuli N, Kharadze D, Chu CC, Won CY. J Polym Sci Pol Chem. 1999;37:391. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo K, Chu CC. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3284. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettinger CJ, Bruggeman JP, Borenstein JT, Langer RS. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2315. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sperling LH. Introduction to Physical Polymer Science. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, N.J: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borschel GH, Kia KF, Kuzon WM, Dennis RG. J Surg Res. 2003;114:133. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng H, Kastrup CJ, Ramanathan R, Siegwart DJ, Ma ML, Bogatyrev SR, Xu QB, Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. ACS Nano. 2010;4:625. doi: 10.1021/nn901319y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.