Abstract

Background:

The emergence of chikungunya (CHIK) infection was observed in Odisha, India in 2006. Thereafter many cases with symptoms suggestive of CHIK were reported from different districts of Southern-Odisha. This study was aimed to know the seroprevalence, clinical presentations and seasonal trends of CHIK infection in this region.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted in a tertiary hospital of this region. Serum samples received in the Department of Microbiology from various districts of Southern-Odisha from April 2011 to March 2012 were included in the study. The samples were tested for CHIK and dengue Immunoglobin M (IgM) antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and malaria parasite by immunochromatographic test (ICT) method.

Results:

Out of the 678 serum samples tested, 174 were positive for CHIK, 15 for dengue and two samples were positive for both CHIK and dengue IgM antibodies. The most affected age group was 16-45 years. Females were more affected than males.

Conclusion:

The seroprevalence of CHIK among the suspected cases was 25.7%. Co-infection with CHIK and dengue was found to be 1.15%. The infection had spread to new areas during this outbreak.

Keywords: Chikungunya, IgM antibodies, seroprevalence

Introduction

Chikungunya (CHIK) virus is an Arbovirus which belongs to the genus Alphavirus and family Togaviridae. CHIK is a viral disease that is spread by the bite of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquito. The name CHIK is derived from the Makonde word which means “that which bends up” describing the stooped posture due to arthritic feature of the disease.[1] The symptoms include sudden onset of crippling arthralgia accompanied with fever, chills, headache, nausea, vomiting, low back pain, and rash lasting for a period of 1-7 days. The disease is often self-limiting and rarely fatal. The incubation period is usually 2-3 days. The acute phase lasts for 2-3 days and may remit for 1-2 days after a gap of 4-10 days resulting in a “saddle back” fever curve. Arthralgias are polyarticular, migratory and predominantly affect the small joints of hands, wrists, and feet, with lesser involvement of larger joints. Maculo-papular rash may be seen typically over the face and trunk. In acute phase most patients have headache and conjunctival redness is seen in some cases. In very rare cases the infection may result in meningo-encephalitis especially in newborns. Pregnant women can pass the virus on to their foetus.[1]

In India, National Institute of Virology (NIV), Pune, is a WHO collaborating center for arboviral diseases. It is engaged in diagnosis, outbreak investigations and preparations of reagents for diagnosis of arboviral infections. It is the only institute in the country that prepares reagents for laboratory diagnosis of CHIK virus. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test used in this study was developed in-house by NIV, Pune. Laboratory diagnosis depends on the quality of sample and time of collection in the course of illness. In first 5 days, viremia is present and can be confirmed by viral culture, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or antigen detection. CHIK IgM becomes detectable around 5 days of fever and persists for several months and Immunoglobin G (IgG) is present by 10-14 days. Serological diagnosis of CHIK by detecting IgM or IgG seroconversion is widely used because it is cheaper and easier to perform. But the disadvantage of antibody testing is that as IgM persists for months a single-raised IgM may not indicate acute infection and there is a possibility of cross-reactivity with other alphaviruses. Antigen detection would be a good alternative, using ELISA and immunochromatography assay (ICA). The sensitivities for diagnosing acute CHIK virus by IgM detection in 1st week were 4-22% and after one week rose to >80% as compared with PCR. A sensitivity of 85-97% and specificity of 90-98% has been reported with samples tested by standard capture IgM ELISA.[2]

The first outbreak of CHIK in India was reported in 1963 in Kolkata, and the last reported outbreak occurred in 1973 in Maharashtra. The present epidemic in India started during December 2005 and the country has so far experienced more than 1,100,000 CHIK infected cases from several Indian states including Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Madhya Pradesh.[3,4] The first outbreak of CHIK infection in the state of Odisha was confirmed during February 2006, marking the emergence of CHIK virus in the state.[5] A study was conducted in a tertiary hospital to know the prevalence of CHIK, clinical presentation, and seasonal trends in the serum samples received from different districts of Southern Odisha, India.

Materials and Methods

Serum samples received in the Department of Microbiology from various districts of Southern Odisha including, rural, tribal, and urban areas during outbreaks, from the month of April 2011 to March 2012, were included in the study. The blood samples collected from patient suffering from fever, joint pain, headache, and rash in areas of outbreaks from the Primary health centers and Community health centers (PHC's and CHC's) under the District Headquarter Hospitals of Ganjam, Malkangiri, Koraput, and Gajapati were sent to the Department of Microbiology along with details of the patient, clinical findings, and investigations done. About 10-15 ml of whole blood sera were collected from the patients after 5 days of fever and transported by a staff of the district headquarter hospital to the Department of Microbiology in an ice box maintained at 2-8°C within 24-48 h.

The samples were tested for CHIK and dengue IgM antibody using IgM antibody capture ELISA kit produced by NIV (Arbovirus Diagnostic NIV, Pune, India). The sensitivity and specificity for the CHIK IgM antibody capture ELISA is 95.00% and 97.22%, respectively, and for dengue IgM antibody capture ELISA is 98.53% and 98.84%, respectively. The tests were carried out following the manufacturer instruction.

Principle of IgM Capture ELISA for CHIK: IgM antibodies in the patient's blood are captured by anti-human IgM (μ chain specific) that are coated on to the solid surface (wells). In the next step, CHIK antigen is added, which binds to captured IgM, if the IgM and antigen are homologous. Unbound antigen is removed during the washing step. In the subsequent steps Biotinylated anti-CHIK monoclonal antibody (CHIK-B) is added followed by Avidin-Histidine rich protein (HRP). Subsequently, substrate/chromogen is added and monitored for development of color. The reaction is stopped by 1NH2SO4. The intensity of color/optical density (OD) is monitored at 450 nm. OD values are directly proportional to the amount of CHIK virus specific IgM antibodies present in the sample. The sample was considered positive for IgM antibody if the OD of the sample exceeds OD of negative control by a factor 4.0 (sample OD ≥ negative OD × 4.0). Both positive and negative controls were used to validate the test. The sera were also tested for malaria parasite by Advantage Malaria card (J Mitra and Co.). Clinical manifestations of the patients were recorded from the data available.

Results

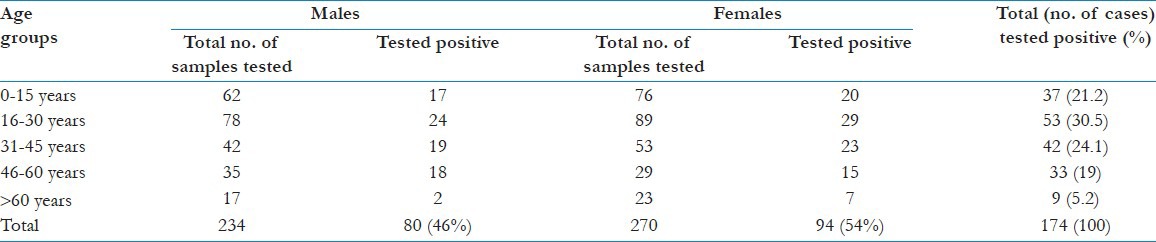

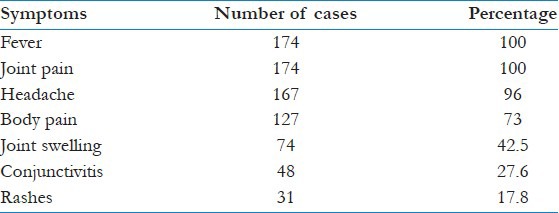

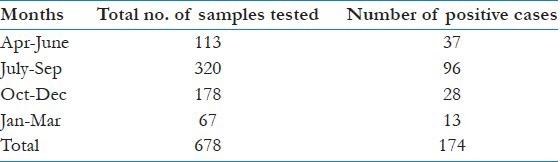

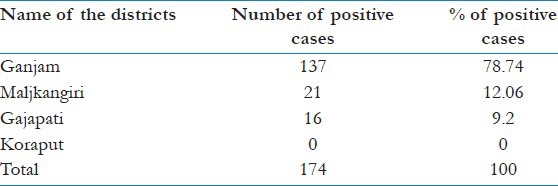

A total of 678 serum samples from suspected cases of CHIK were received during the period from April 2011 to March 2012, out of which 174 (25.7%) samples were positive for CHIK. Majority of the cases were from the age group of 16-30 years (30.5%) followed by 31-45 years (24.1%). Of the total number of affected cases, 54% were females and 46% were males [Table 1]. Fever and joint pain was seen in all the cases, headache in 96%, and body pain in 73% of seropositive cases. Joint swelling, conjunctivitis and rashes were observed in 42.5%, 27.6%, and 17.8% seropositive cases respectively [Table 2]. A seasonal peak was seen in the months of July to August [Table 3]. All the cases were negative for malaria parasite and 15 cases were positive for dengue but 2 (1.15%) cases were found to be positive for both dengue and CHIK IgM antibodies. The districts from where the serum samples were received were, Ganjam, Malkangiri, Koraput, and Gajapati. Seropositivity was maximum from the different blocks and villages of Ganjam district (78.74%) [Table 4, Figure 1].

Table 1.

Age-sex distribution of the chikungunya seropositive cases

Table 2.

Clinical presentations in the chikungunya seropositive case

Table 3.

Seasonal distribution of the chikungunya seropositive cases

Table 4.

Distribution of positive cases in the districts from where samples were received

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the districts from where samples were received for serodiagnosis of chikungunya showing the percentage of sero-positivity

Discussion

After a quiescence of about three decades, outbreak of CHIK with sporadic cases of dengue is being reported from different parts of India, whereas, Odisha with no previous record of CHIK infection experienced its first epidemic in 2006. After the emergence of CHIK virus in the state it spread in rural and coastal areas of nearly half of the districts between 2006 and 2007.[5] In our study in between 2011 and 2012 we found that there were some outbreaks in Southern districts of Odisha showing a seasonal variation peaking in the months of July to September which coincided with the monsoon and post-monsoon periods when the vector density peaks. There are reports of the presence of Aedes species in varying densities in different regions of the State which indicate potential for spread to other areas. The CHIK virus is also known to spread through transovarial transmission in the mosquitoes and possible sylvatic cycles. All these indicate possibility of spread of the infection to other areas of the region.[5] We found that even after the emergence of CHIK in 2006, outbreaks and sporadic cases of CHIK were seen in several districts of Southern Odisha during the period of April 2011 to March 2012.

Out of the total 678 serum samples received, 174 samples were positive for CHIK virus, 15 samples were positive for dengue and two were positive for both dengue and CHIK. In 1967, co-infections with dengue and CHIK viruses were reported from Kolkata. Subsequent serological investigations in Southern India indicated that the two viruses can co-exist in the same host.[6] The first case report of CHIK and dengue co-infection confirmed by molecular assays was from Sri Lanka.[7] Antibodies to dengue virus were found in 0.9-9.9% of CHIK patients in India and to both CHIK and dengue virus in 0.4-4.3% of patients, confirming that the two viruses co-circulate in this country.[8] In our case, co-infection with dengue and CHIK was found to in 1.15% cases as compared to 2.7% in a study by Kalawat, et al.[9]

The number of cases was more in the months of July to September and less during the months of January to March. This type of seasonal variation was seen in most of the studies, because of the increase in vector density during the rainy season.[4,5,10] The age group 15-45 years was mostly affected whereas lower number of cases were seen from elderly persons >60 years in our study. In the gender distribution, the number of affected females was more than males. These findings were much similar to the pattern shown by Balasubramaniam, et al. and Dwibedi, et al.[4,5] However, in the study conducted by Sharma, et al., it was found that the age group 5-9 years had highest percentage of morbidity and males were more frequently affected than females. During a study conducted by Dwibedi, et al.[5] it was seen that Ganjam and Gajapati were the two districts affected in Southern Odisha by the CHIK outbreak, but in our study seropositivity was seen in samples from Malkangiri, Ganjam and Gajapati.

Conclusion

CHIK affects humans of all age groups worldwide. In the present study there was no mortality but the morbidity was high with loss of work as the population most affected belonged to the age group of 16-45 years. The virus is spreading to new areas in this part of the state, as there is no herd immunity to the virus. The Aedes mosquito is present in varying density in different regions of the state and may be a potential for the spread to other areas. In Indian setting, low socio-economic conditions, overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions facilitated by the presence of the Aedes vector species contribute to the spread of the CHIK virus to wider areas. Therefore, screening of CHIK, dengue, and other arboviruses is necessary, because though the clinical features are similar the outcomes may vary.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Chhabra M, Mittal V, Bhattacharya D, Rana U, Lal S. Chikungunya fever: A re-emerging viral infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:5–12. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.38850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sam IC, Chua CL, Chan YF. Chikungunya virus diagnosis in the developing world: A pressing need. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:1089–91. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur P, Ponniah M, Murhekar MV, Ramachandran V, Ramachandran R, Raju HK, et al. Chikungunya outbreak, South India, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1623–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.070569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramaniam SM, Krishnakumar J, Stephen T, Gaur R, Appavoo N. Prevalence of chikungunya in urban field practice area of a private medical college, Chennai. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:124–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.84131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwibedi B, Sabat J, Mahapatra N, Kar SK, Kerketta AS, Hazra RK, et al. Rapid spread of chikungunya virus infection in Orissa: India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:316–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yergolkar PN, Tandale BV, Arankalle VA, Sathe PS, Sudeep AB, Gandhe SS, et al. Chikungunya outbreaks caused by African genotype, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1580–3. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hapuarachchi HA, Bandara KB, Hapugoda MD, Williams S, Abeyewickreme W. Laboratory confirmation of dengue and chikungunya co-infection. Ceylon Med J. 2008;53:104–5. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v53i3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pialoux G, Gaüzère BA, Jauréguiberry S, Strobel M. Chikungunya. An epidemic arbovirosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:319–27. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalawat U, Sharma KK, Reddy SG. Prevalence of dengue and chickungunya fever and their co-infection. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:844–6. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.91518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mavalankar D, Shastri P, Bandyopadhyay T, Parmar J, Ramani KV. Increased mortality rate associated with chikungunya epidemic, Ahmedabad, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:412–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1403.070720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]