Abstract

Background

In Drosophila melanogaster, commissureless (comm) function is required for proper nerve cord development. Although comm orthologs have not been identified outside of Drosophila species, some insects possess orthologs of Drosophila comm2, which may also regulate embryonic nerve cord development. Here, this hypothesis is explored through characterization of comm2 genes in two disease vector mosquitoes.

Results

Culex quinquefasciatus (West Nile and lymphatic filiariasis vector) has three comm2 genes that are expressed in the developing nerve cord. Aedes aegypti (dengue and yellow fever vector) has a single comm2 gene that is expressed in commissural neurons projecting axons toward the midline. Loss of comm2 function in both A. aegypti and D. melanogaster was found to result in loss of commissure defects that phenocopy the frazzled (fra) loss of function phenotypes observed in both species. Loss of fra function in either insect was found to result in decreased comm2 transcript levels during nerve cord development.

Conclusions

The results of this investigation suggest that Fra downregulates repulsion in precrossing commissural axons by regulating comm2 levels in both A. aegypti and D. melanogaster, both of which require Comm2 function for proper nerve cord development,

Keywords: commissureless, development, nervous system, mosquito, Aedes aegypti, Culex quinquefasciatus, Drosophila melanogaster, frazzled

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, knockdown studies have suggested that axon guidance gene function has diverged in the insect embryonic ventral nerve cord (Clemons et al., 2011; Haugen et al., 2011; Evans and Bashaw, 2012). For example, an siRNA-mediated knockdown strategy was used to study the role of the Netrin receptor frazzled (fra) during Aedes aegypti embryonic nerve cord development (Clemons et al., 2011). The results of this investigation, the first targeted knockdown of a gene during vector mosquito embryogenesis, suggest that although Fra plays a critical role during development of the A. aegypti ventral nerve cord, mechanisms regulating embryonic commissural axon guidance have diverged in dipteran insects. Specifically, loss of Aae fra results in thin and missing commissural axons, defects which are qualitatively similar to those observed in D. melanogaster fra null mutants. However, complete commissure loss is observed in A. aegypti fra knockdown embryos, which bear more resemblance to the Drosophila commissureless (comm) loss of function phenotype (Seeger et al., 1993) than the Drosophila fra loss of function phenotype (Kolodziej et al., 1996).

Mutations in the D. melanogaster comm gene were initially uncovered from a screen for mutations that affect development of the Drosophila embryonic CNS axons pathways (Seeger et al., 1993). The comm gene is the most extensively studied of the three comm family genes (comm, comm2, and comm3) in D. melanogaster (Keleman et al., 2002). Mutants for comm display a unique phenotype, the complete absence of most axon commissures. Cloning and sequencing of the comm gene revealed that it encodes a novel transmembrane protein (Tear et al., 1996). Subsequent studies revealed that Comm functions in neurons to regulate the intracellular trafficking and surface levels of Robo (Keleman et al., 2002; McGovern and Seeger, 2003; Keleman et al., 2005), receptor for the midline repellent Slit. The choice of crossing (commissural) or noncrossing (ipsilateral) axon pathways is regulated by the differential sensitivity of axons to Slit (reviewed by (Dickson, 2002). Ipsilateral axons lacking Comm expression are repelled by Slit-Robo signaling and fail to cross the midline. Commissural axons, which express Comm and consequently lack Robo surface expression, are initially insensitive to Slit-mediated repulsion and respond to Net attractive midline cues. Once commissural axons reach the midline, Comm expression is downregulated, and these neurons are repelled from the midline by Slit-Robo signaling (Kidd et al., 1999; Stein and Tessier-Lavigne, 2001; Dickson and Gilestro, 2006). Thus, the ability of Comm to control Robo levels is critical for proper nerve cord formation.

Despite the importance of comm gene function in the D. melanogaster nerve cord, no comm gene ortholog has been detected outside of the Drosophila species (Waterhouse et al., 2013). However, orthologs of the Drosophila comm2 and comm3 genes, neither of which have been extensively characterized in Drosophila, have been identified in other arthropods, including vector mosquitoes (Behura et al., 2011). It was hypothesized that these comm family genes might function during vector mosquito nerve cord development. In this investigation, we perform phylogenetic and expression analyses of comm family orthologs in C. quinquefasciatus and A. aegypti. The role of the A. aegypti comm2 gene, the only comm family ortholog in this species, was assessed through siRNA-mediated silencing. The function of Aae comm2 was compared to that of its closest D. melanogaster comm family ortholog, D. melanogaster comm2, which was also assessed for comparison.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mosquito comm family genes

Previous comparative genomic analyses of developmental genes in the D. melanogaster, A. aegypti, C. quinquefasciatus, and A. gambiae genomes revealed changes in the number of axon guidance genes in these species (Behura et al., 2011). While three comm family genes (comm, comm2, and comm3) are found in D. melanogaster, no comm family genes have been identified in A. gambiae. However, three comm family genes were identified in C. quinquefasciatus (CPIJ016283, CPIJ016285, CPIJ017280), while a single comm family gene has been identified in the A. aegypti genome (AAEL007250). These genes were noted to be Drosophila comm2/comm3 orthologs (Behura et al., 2011). Sequence analyses were performed to further explore the relationship between these mosquito comm family genes with each other and with those of other arthropods (Fig. 1).

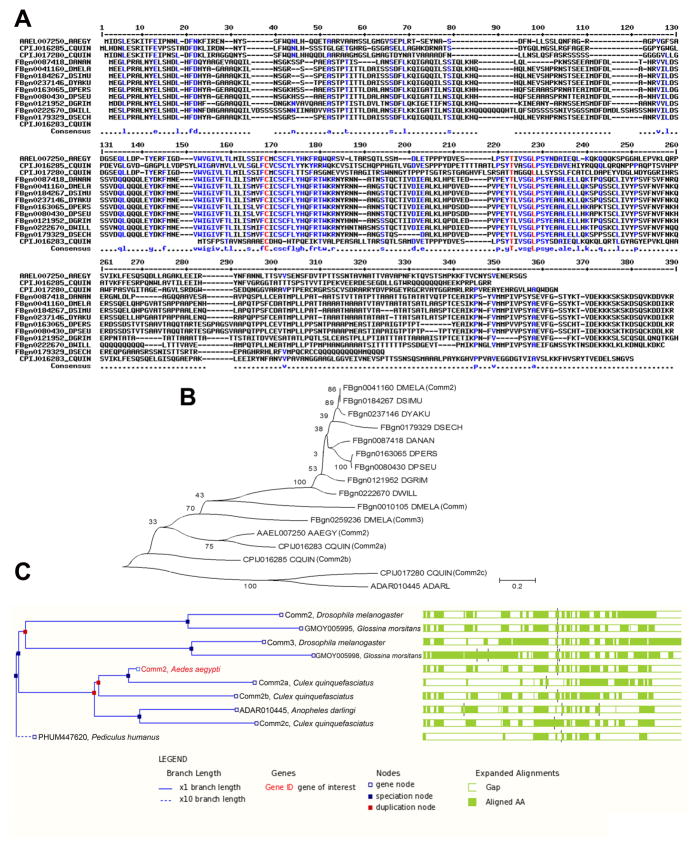

Fig. 1. Sequence analysis of insect Comm family proteins.

A. A partial multiple alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of the N-termini of predicted comm2 orthologs among mosquito and fruit fly species is shown. The gene accession numbers and species are indicated to the left of the sequences in the alignment. The amino acid position of aligned sequences is indicated at the top, while the consensus sequence of the alignment is shown below the aligned sequences. B. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of C. quinquefasciatus Comm proteins along with orthologous proteins identified in A. aegypti and Drosophila species is shown. All three Comm family proteins of D. melanogaster (Comm, Comm2, and Comm3) are included in the tree. The percentage of replicate trees in which proteins clustered together through bootstrap testing is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The scale of the evolutionary distances as units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site is shown. C. The amino acid sequence conservation of selected orthologs of AAEL007250, as inferred from the GBrowse tool of VectorBase (2009), shown at right corresponds to the phylogenetic relationships among the proteins shown on the left. The percentages of sequence identities, sequence gaps and details of tree nodes are shown below the figure as captions generated by Gbrowse. Abbreviations in this figure are as follows: A. aegypti = AAEGY, C. quinquefasciatus = CQUIN, D. ananassae = DANAN, D. melanogaster = DMELA, D. simulans = DSIMU, D. yakuba = DYAKU, D. persimilis = DPERS, D. pseudoobscura = DPSEU, D. grimshawi = DGRIM, D. willistoni = DWILL, D. sechellia = DSECH.

The amino acid sequence conservation pattern among Drosophila and mosquito Comm family proteins is shown in Fig. 1A, C. Phylogenetic comparisons suggest that the A. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus Comm family proteins more closely resemble each other than they do any of the Drosophila Comm family proteins (Fig. 1B, C). D. melanogaster Comm family proteins bear a highly conserved 22 amino acid sequence (residues 215–236 in D. melanogaster Comm; Keleman et al., 2002). This sequence is well conserved in AAEL007250, CPIJ16283, and CPIJ16285 (Fig. 1A). However, comparison of the motif maps of CPIJ017280 with D. melanogaster Comm2 (FBgn0041160) based on Dayhoff weight estimates of local sequence similarities (Leontovich et al. 1993) revealed that the conserved cytoplasmic domain is either lost or extensively mutated in CPIJ017280 protein (Fig. 1A and data not shown). The D. melanogaster Comm protein also contains a heterotetrameric adaptor protein binding site motif LPSY (Wolf et al., 1998) which is conserved in D. melanogaster Comm2, but not Comm3. This domain is required for endosomal sorting of Comm and Comm2, as well as downregulation of Robo and the promotion of midline crossing (Keleman et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2003). An LPSY motif is found in all of the A. aeygpti and C. quinquefasciatus Comm family proteins, suggesting that with reference to this functionally significant motif, these proteins are more comparable to D. melanogaster Comm2 than Comm3. This observation suggests that the A. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus genes are comm2 orthologs.

A comm2 orthology assignment is supported by OrthoDB for all of the A. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus comm family genes except CPIJ16283, which is referred to as a comm3 ortholog (Waterhouse et al., 2013). Still, given the presence of the LPSY motif in CPIJ16283 and our phylogenetic analyses which group it most closely with AAEL007250 (Fig. 1B), we argue that comm2 orthology assignments for all of the three C. quinquefasciatus genes is appropriate. Thus, in addition to naming AAEL007250 Aae comm2, we will refer to CPIJ16283 as Cqu comm2a, CPIJ16285 as Cqu comm2b, and CPIJ017280 as Cqu comm2c. Moreover, in addition to the detection of brain and head tissue expression of all these genes, analysis of their expression in developing mosquito embryonic nerve cords suggests that they may function to regulate development of this tissue (Fig. 2, 3), a hypothesis which is functionally examined in A. aegypti in this investigation (see below). Functional testing of this hypothesis in C. quinquefasciatus, which could further support or potentially refute the comm2 orthology assignment of these genes, will be interesting. However, this will first require optimization of knockdown methodology in C. quinquefasciatus embryos.

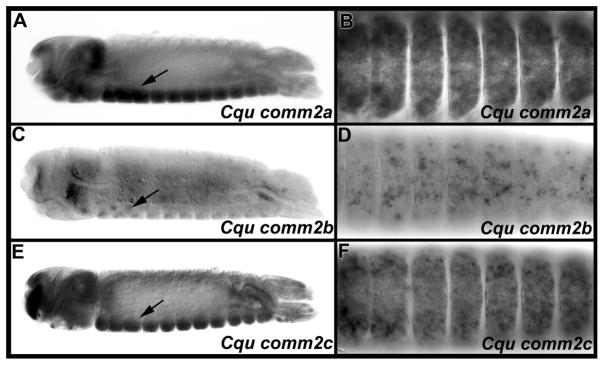

Fig. 2. Three C. quinquefasciatus comm family genes are expressed in the developing nerve cord.

Cqu comm2a (A, B), Cqu comm2b (C, D), and Cqucomm2c (E, F) transcripts are detected in the developing C. quinquefasciatus nerve cord and head region (both brain and overlying tissue). Arrows mark nerve cord expression on the ventral sides of 22 hour old embryos; lateral views oriented anterior left and ventral down are shown. Ventral views of CNS expression in these same animals (B, D, F; anterior is again oriented left) are shown to the right of panels A, C, and E, respectively. All three genes are widely expressed in the developing nerve cord during the period of commissural axon guidance, but the neural expression levels of Cqu comm2b (F) are markedly less than the neural expression levels of the other two comm2 genes (B, D).

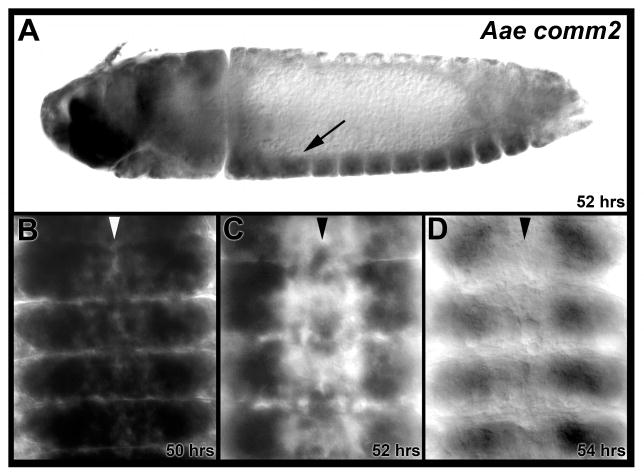

Fig. 3. Aae comm2 is expressed in the developing nerve cord.

Aae comm2 expression is detected during A. aegypti embryonic ventral nerve cord development. (A) An arrow marks nerve cord expression in a lateral view of a 52 hour old embryo oriented anterior left and ventral down. Transcripts are also detected in the brain and overlying head tissue. (B–D) Transcript levels peak in the ventral nerve cord at 50 hours (B) and are observed in a more restricted set of neurons by 52 hours (C). At 54 hours (D), when most commissural axons have crossed the midline, expression in the nerve cord has diminished. Filleted nerve cords oriented anterior upward are shown in B–D, in which the midline is marked by arrowheads.

In summary, these sequence analysis studies revealed that despite the lack of a detectable comm family gene ortholog in A. gambiae, C. quinquefasciatus has three comm2 genes, while A. aegypti has one. Interestingly, a single comm family gene, a probable comm2 ortholog, has been discovered in Anopheles darlingi (Fig. 1B, C, Lawson et al., 2009), suggesting that comm genes were not lost in all anopheline mosquitoes. We of course cannot eliminate the possibility that an A. gambiae comm family gene exists, but has not yet been detected due to sequencing gaps. This possibility aside, one likely explanation for these combined findings is that a single comm2 gene existed when the Drosophila and mosquito lineages split. Some mosquito species retained the single gene (i.e. A. aegypti and A. darlingi), and others lost it (A. gambiae), while the comm gene family expanded in C. quinquefasciatus and D. melanogaster. In addition, it is likely that the comm2 gene family in C. quinquefasciatus may be evolving faster than the comm family of other dipterans. By estimating evolutionary distance in a pair-wise manner between species, it was found that the C. quinquefasciatus Comm2 family has a relatively higher number of amino acid substitutions per site than other insects (Table 1). The data presented in Table 1 demonstrate that the pair-wise distances among the three C. quinquefasciatus Comm2 proteins are consistently higher than the pair-wise distances of Comm2 proteins within Drosophila or between Drosophila and A. aegypti. Hence, the C. quinquefasciatus proteins distinctly differ in the rate of amino acid substitutions compared to that of A. aegypti or Drosophila.

Table 1.

Pairwise distances between genes calculated using MEGA4. The number of amino acid substitutions per site from analysis between sequences is shown. 1: AAEL007250_AAEGY, 2: CPIJ016285_CQUIN, 3: CPIJ017280_CQUIN, 4: FBgn0087418_DANAN, 5: FBgn0121952_DGRIM, 6: FBgn0041160_DMELA, 7: FBgn0163065_DPERS, 8: FBgn0080430_DPSEU, 9: FBgn0179329_DSECH, 10: FBgn0184267_DSIMU, 11: FBgn0222670_DWILL, 12: FBgn0237146_DYAKU, 13: CPIJ016283_CQUIN. These species abbreviations are defined in the legend of Fig. 1.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | 1.1 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 1.3 | 2.0 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | ||||||||||

| 5 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 | |||||||||

| 6 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||||||

| 7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |||||||

| 8 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | ||||||

| 9 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |||||

| 10 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| 11 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |||

| 12 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | ||

| 13 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

Detailed analysis of comm2 expression during A. aegypti nerve cord development

Given the lack of a detectable comm gene outside the drosophilids and the apparent lack of any comm family (comm, comm2, or comm3) gene in some insects (Behura et al., 2011; Evans and Bashaw, 2012), it is possible that the requirement for comm family gene function is not retained outside of Drosophila. However, given the expansion of C. quinquefasciatus comm2 genes, all of which are expressed in the developing nerve cord (Fig. 2), it is also possible that comm family gene function is in fact required outside of D. melanogaster, a concept which has never been experimentally tested. To explore this, we opted to assess comm2 gene function in A. aegypti because it has retained a single comm family ortholog (Fig. 1), and also due to the fact that we recently optimized embryonic knockdown strategies in this species (Clemons et al., 2010a; Clemons et al., 2011; Haugen et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2013), which is to our knowledge the only mosquito species in which embryonic RNAi knockdown studies have been published to date.

First, Aae comm2 expression was assessed in detail during A. aegypti embryonic CNS development. Like the Cqu comm2a, b, and c genes (Fig. 2), Aae comm2 is expressed in the brain and overlying head tissue and in many neurons of the embryonic nerve cord at the onset of commissural axon guidance toward the midline (Fig. 3A). Expression levels of Aae comm2 in the developing nerve cord peak at ~50 hours (Fig. 3B) and then begin to subside (Fig. 3C). Nerve cord expression of Aae comm2 has diminished by ~54 hrs (Fig. 3D), which corresponds to the time at which most axons have reached the midline (Clemons et al., 2011). These aspects of the Aae comm2 ventral nerve cord expression pattern are quite similar to that which has been described for D. melanogaster comm, which has been extensively characterized (Keleman et al., 2002), with the exception that D. melanogaster comm has very prominent midline expression, the levels of which are often stronger than comm expression in more lateral neurons (Keleman et al., 2002). The expression pattern suggests that Aae comm2 functions primarily in neurons and not in midline cells, which is consistent with the finding that D. melanogaster comm function is required in neurons, but not at the midline (Keleman et al., 2002).

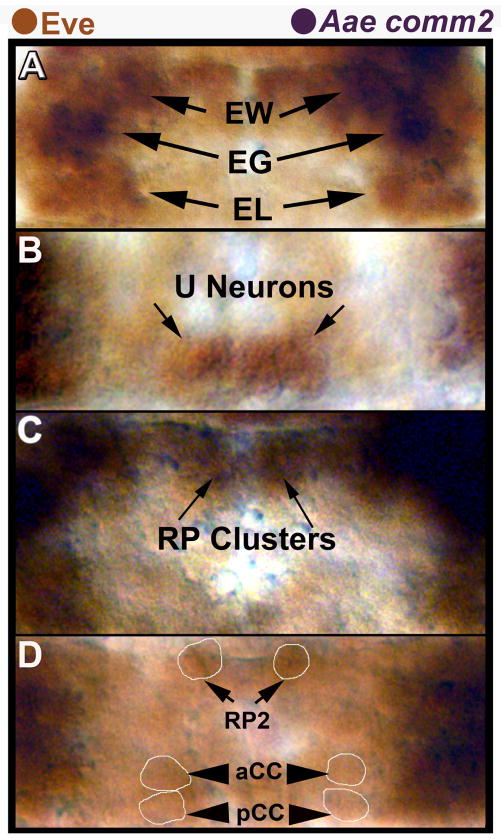

D. melanogaster comm expression has been assessed in detail in both crossing and non-crossing axons (Keleman et al., 2002). These expression studies indicated that D. melanogaster comm is not expressed in non-crossing axons, but is detected specifically in commissural neurons as they are being guided to the midline and later extinguished after midline crossing. To determine if Aae comm2 is expressed in a comparable manner, we first needed to identify crossing and non-crossing neurons in the ventral nerve cord of this species. Analysis of Even-skipped (Eve) expression has facilitated identification of homologous neurons in a wide variety of arthropods (Duman-Scheel and Patel, 1999). The Eve expression pattern is well conserved in A. aegypti (Fig. 4), which allowed for the identification of specific neurons. The Eve-positive RP2, aCC, pCC, U, and EL neurons do not cross the midline and do not express comm in D. melanogaster (Keleman et al., 2002). These neurons, all of which are also marked by Eve expression in A. aegypti, do not express Aae comm2 (Fig. 4A, B, D). Several comm2-positive homologous cells were identified based on their positional locations with respect to Eve-expressing neurons in the A. aegypti nerve cord. The EG (Fig. 4A), RP1, RP3, and RP4 neurons (Fig. 4C), all of which cross the midline, were found to express Aae comm2. These expression analyses suggest that Aae comm2, like D. melanogaster comm, is expressed in crossing but not non-crossing neurons. Moreover, Aae comm2 expression fades by the time that axons have reached the midline (Fig. 3D), which presumably facilitates Slit-Robo mediated axon repulsion from the midline as it does in Drosophila (Keleman et al., 2002).

Fig. 4. Lack of Aae comm2 expression in neurons that do not cross the midline.

The EL (A) and U (B) neuron clusters, RP2, aCC, and pCC neurons (D) are marked by expression of Eve protein (brown). These Eve-positive neurons do not express Aae comm2 mRNA (dark purple, A–D), and their axons do not cross the midline. The EG, EW (A) and RP neuron (RP1, 3, 4; RP2 is out of focus) clusters (C) were positionally identified with respect to Eve-positive neurons; these neurons (with the exception of RP2) project axons to the midline and express Aae comm2 (dark purple). All images are oriented anterior upward and correspond to different segments/focal planes of the nerve cord from a single filleted 51 hour old embryo. Ventral focal planes of the nerve cord are shown in A and B, while C shows a more dorsal plane of focus. Panel D shows the dorsal-most plane of focus in this nerve cord. Light Eve staining permitted examination of comm2 expression in Eve-positive neurons of A. aegypti embryos in which tissue autofluorescence hinders fluorescent immunohistochemistry. Lightly-stained Eve-positive cell bodies were circled in some panels (D) to facilitate interpretation of these data.

Knockdown of comm2 in A. aegypti results in a commissureless phenotype

Expression data (Fig. 3,4) support the notion that Aae comm2 function is required during nerve cord development. To examine this possibility, the putative role of Aaecomm2 was assessed through siRNA-mediated knockdown experiments, which were recently shown to be an effective method of inhibiting gene expression during embryonic development of A. aegypti (Clemons et al., 2011; Haugen et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2013). Experimental or control siRNAs were microinjected at the pre-cellular blastoderm stage. Two siRNAs corresponding to different regions of the Aae comm2 gene, comm2-siRNA 1 and comm2-siRNA 2, were used to target this gene. Control experiments were performed using previously designed control siRNA (Nguyen et al., 2013) which does not bear high sequence similarity to other genes in the A. aegypti genome. 53 hour old embryos were assessed post-injection of comm2-siRNA 1, comm2-siRNA 2, or control siRNA. In situ hybridization assays demonstrated that a majority of comm2-siRNA 1 (79%, n=33) and comm2-siRNA 2 (74%, n=31) injected embryos lacked comm2 expression in the developing ventral nerve cord (Fig. 5B, C), while control-injected embryos displayed comm2 expression levels which resemble those of wild-type embryos (Fig. 5A, n=46).

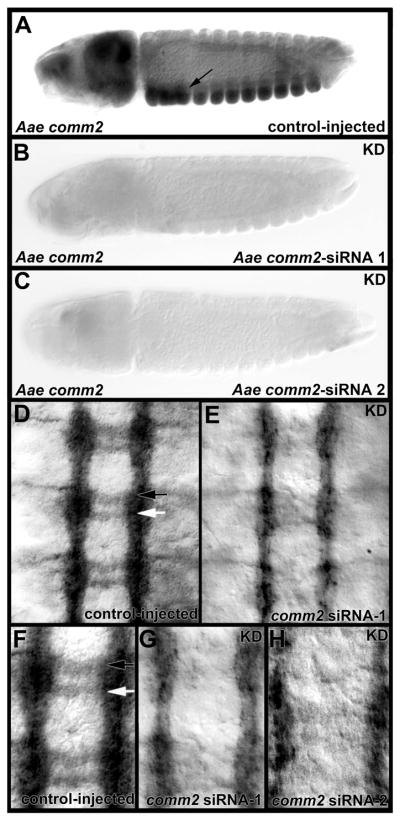

Fig. 5. Knockdown of Aae comm2 results in a commissureless phenotype.

Aae comm2 knockdown (KD) was confirmed through whole-mount in situ hybridization, which demonstrated that two siRNAs targeting comm2, siRNA-1 (B) and siRNA-2 (C), resulted in loss of comm2 transcripts throughout the entire embryo, including the nerve cord. comm2 levels were not noticeably altered by injection of control siRNA (A, arrow marks ventral nerve cord expression). Lateral views are shown in panels A–C which are oriented anterior left and ventral downward. In D–H, anti-acetylated tubulin staining marks the axons in the filleted ventral nerve cords (oriented anterior upward) of control siRNA-injected (D, F) and comm2 knockdown siRNA-injected (E, G, H) embryos at 53 hours of development. In control-injected nerve cords (D, F), which have a wild-type appearance, the anterior commissure is marked by a black arrow while a white arrow marks the posterior commissure. Knockdown of comm2 results in loss of commissural axons (E, G, H). Comparable results were obtained with two different siRNAs (comm2 siRNA-1 in E, G; comm2 siRNA-2 in H). Panels F and G show high magnification views of the nerve cords in D and E, respectively.

The impact of comm2 knockdown on A. aegypti embryonic nerve cord development was assessed through anti-acetylated tubulin staining at 53 hours of development. Although control-injected animals had normal nerve cord development (n=71, Fig. 5D, F, Table 2), commissure formation was disrupted in embryos injected with either comm2-siRNA 1 (n=35, Fig. 5E, G) or siRNA 2 (n=51, Fig. 5H). Comparable phenotypes were generated through injection of comm2- siRNA 1 or 2 (Fig. 5E, G, H), suggesting that the commissureless phenotype observed was not the result of off-site targeting by either siRNA. 71% of comm2-siRNA 1 injected embryos and 51% of comm2-siRNA 2 injected embryos displayed severe nerve cord phenotypes in which most segments had commissure defects. Individual segments were scored in a subset of these animals, and the percentages of segments with moderate (thinning of commissures) or severe (loss/near loss) phenotypes are provided in Table 2. These data indicate that Aae Comm2 function is required for proper commissure formation in A. aegypti.

Table 2.

A. aegypti comm2 knockdown phenotypes. 53 hour old embryos were assessed post-injection of comm2-siRNA 1, comm2-siRNA 2, or control siRNA. Commissure loss phenotypes were scored in individual segments following anti-acetylated tubulin staining. Percentages of segments with wildtype, moderate (thinning of commissures), or severe (loss/near loss of commissures) phenotypes are indicated. Data were compiled from three or more replicate experiments.

| n | % segments with no commissure defects | % segments with moderate commissure defects | % segments with severe commissure defects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| control-injected | 58 | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| comm2-siRNA 1 | 42 | 5 | 21 | 74 |

| comm2-siRNA 2 | 81 | 2 | 21 | 77 |

D. melanogaster comm2 is also required for nerve cord development

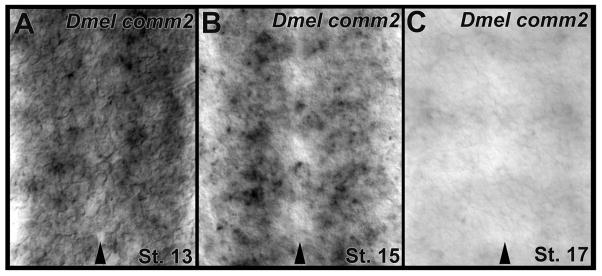

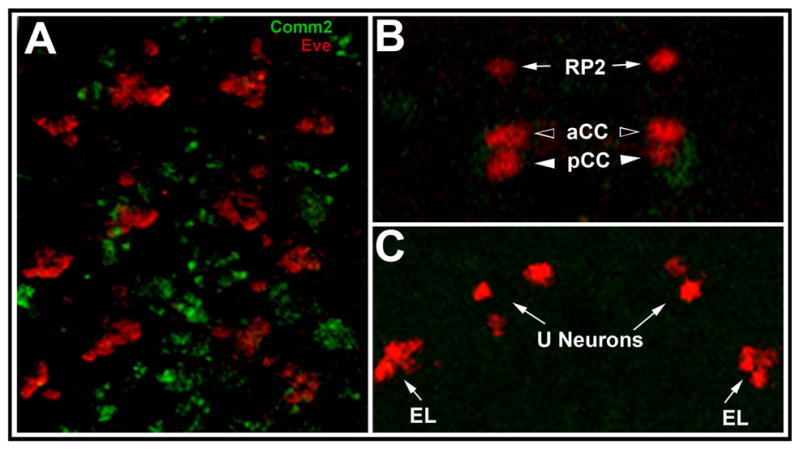

The results of the A. aegypti knockdown experiments suggested that D. melanogaster Comm2, the ortholog of Aae Comm2, may also function during nerve cord development. Expression of D. melanogaster comm2 transcript is detected in the developing embryonic nerve cord (Fig. 6A, B), brain, and head tissue (not shown) in a pattern which resembles that of Aae comm2 (Fig. 3). High levels of D. melanogaster comm2 transcript are detected in the nerve cord at stage 13 (Fig. 6A), and by Stage 15, expression of comm2 is observed in a more restricted set of D. melanogaster neurons (Fig. 6B). Like Aae comm2, expression of D. melanogaster comm2 diminishes once the majority of commissural axons have crossed the midline (Fig. 6B). It has been suggested both in the discussion of Keleman et al. (2002) and also in the doctoral thesis of Choi (2003) that D. melanogaster Comm2, like D. melanogaster Comm, prevents Robo from reaching the cell surface. If this is true, then D. melanogaster Comm2, like Comm (Keleman et al., 2002) should not be expressed in neurons which do not project axons toward the midline. This was assessed in D. melanogaster in the same manner in which it was examined in A. aegypti (Fig. 4), through the combined analysis of Eve and Comm2 expression during nerve cord development. The results of these experiments (Fig. 7) were comparable to those obtained for A. aegypti (Fig. 4). The D. melanogaster Eve-positive EL, U, aCC, pCC, and RP2 neurons lack expression of Comm2 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Expression of comm2 during D. melanogaster nerve cord development. comm2 expression is detected during D. melanogaster embryonic ventral nerve cord development. High levels of transcript are detected at Stage 13 (A) and are observed in a more restricted set of neurons at Stage 15 (B). By stage 17 (C), when most commissural axons have crossed the midline, expression in the nerve cord has significantly diminished. Arrowheads in A–C mark the midline; filleted nerve cords are oriented anterior upward in these panels.

Fig. 7.

Lack of D. melanogaster Comm2 expression in axons that do not cross the midline. (A) Non-overlapping expression of Eve (red) and Comm2 (green, MB01146 reporter) in a stage 14 D. melanogaster embryo. Three abdominal segments of a maximum projection image of the nerve cord which is oriented anterior upward are shown. No Comm2 expression is detected in the Eve-positive RP2, aCC, pCC (B), U and EL neurons (C), none of which project axons to the midline. Anterior is oriented upward in all panels. A single section through a dorsal focal plane of the posterior-most segment of A is shown in B, while a single section through a ventral portion of this same segment is shown in C.

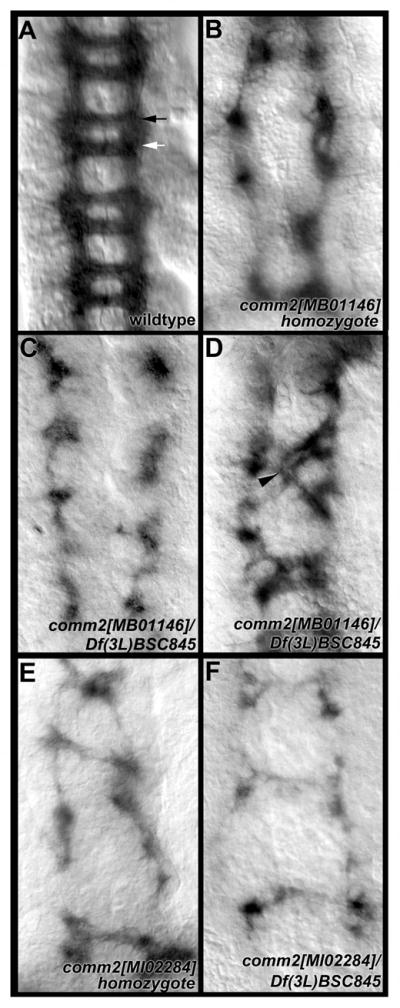

In his doctoral thesis, Choi (2003) suggested that loss of function mutations in D. melanogaster comm2 result in commissure loss resembling that of the comm mutant (Seeger et al., 1993). Moreover, the comm2 mutants that he described also displayed a general distortion of the nerve cord that is not observed in comm mutants. To confirm these observations, commissure formation was examined through analysis of two additional comm2 mutant strains, comm2[MB01146] and comm2[MI02284] (see methods section for additional details), neither of which were described by Choi (2003). comm2[MB01146] mutant embryos display both significant commissure loss (Fig. 8B, Table 3) as well as a general distortion of the nerve cord. Animals that are heterozygous for the comm2[MB01146] mutation in combination with Df(3L)BSC845 (Fig. 8C, D, Table 3), a deletion in the region, displayed a comparable loss of commissure phenotype. The percentage of segments with severe commissure loss observed in embryos of these two genotypes was not significantly different (P>0.1, Table 3). These results suggest that comm2[MB01146] is an amorphic allele. Significant commissure loss and distortion of the nerve cord was also observed in animals homozygous for comm2[MI02284] (Fig. 8E, Table 3). Animals heterozygous for comm2[MI02284] in combination with Df(3L)BSC845 (Fig. 8F) have phenotypes that are comparable to those of comm2[MI02284] homozygotes (Fig. 8E). The percentage of segments with severe commissure loss observed in embryos of these two genotypes was not significantly different (P>0.1, Table 3), suggesting that the comm2[MI02284] allele is also an amorphic comm2 allele. These results, in combination with those of Choi (2003), demonstrate that Comm2 is required for nerve cord formation in D. melanogaster.

Fig. 8. Loss of D. melanogaster comm2 function results in a commissureless phenotype.

P102 staining marks axons of the ventral nerve cord in wild-type (A) and comm2 mutant (B–F) embryos. Significant commissure loss, as well as longitudinal breaks, are observed in comm2 mutants (B–F), in which the overall appearance of the nerve cord is generally distorted. Genotypes are noted in each panel. Commissure loss phenotypes are quantified for each genotype in Table 3. The black arrow in A marks the anterior commissure, while the white arrow marks the posterior commissure. In D, the arrowhead marks axons that have extended across the segmental boundary. Stage 15 nerve cords oriented anterior upward are shown in each panel.

Table 3. D. melanogaster comm2.

knockdown commissure loss phenotypes. BP102-stained stage 15–16 D. melanogaster embryos were assessed for commissure loss phenotypes. Percentages of segments with wildtype, moderate (thinning of commissures) or severe (loss/near loss of commissures) phenotypes are indicated. Data were compiled from three or more replicate experiments.

| n | % segments with no commissure defects | % segments with moderate commissure defects | % segments with severe commissure defects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| wildtype | 110 | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| comm2[MB01146]/comm2[MB01146] | 65 | 0% | 6% | 94% |

| comm2[MB01146]/Df(3L)BSC845 | 47 | 0% | 11% | 89% |

| comm2[MI02284]/comm2[MI02284] | 107 | 3% | 26% | 71% |

| comm2[MI02284]/Df(3L)BSC845 | 54 | 0% | 22% | 78% |

These analyses suggest that the function of Comm2 is generally well conserved between A. aegypti and D. melanogaster. However, it is noted that the nerve cord has an overall more distorted appearance in D. melanogaster comm2 mutants (Fig. 8), which also display frequent breaks in the longitudinal connectives that were not observed in A. aegypti comm2 knockdown embryos (Fig. 5E, G, H). Furthermore, the D. melanogaster comm2 mutants assessed in this study had embryonic segments in which the few existing commissural axons passed into adjacent segments (one example in a comm2[MB01146]/Df(3L)BSC845 heterozygote is shown in Fig. 8D). Thus, despite the generally well conserved function of Comm2 in the two species, some differences in the loss of function phenotypes do exist. Similar observations were made in our previous fra (Clemons et al., 2011) and semaphorin-1a (Haugen et al., 2011) investigations.

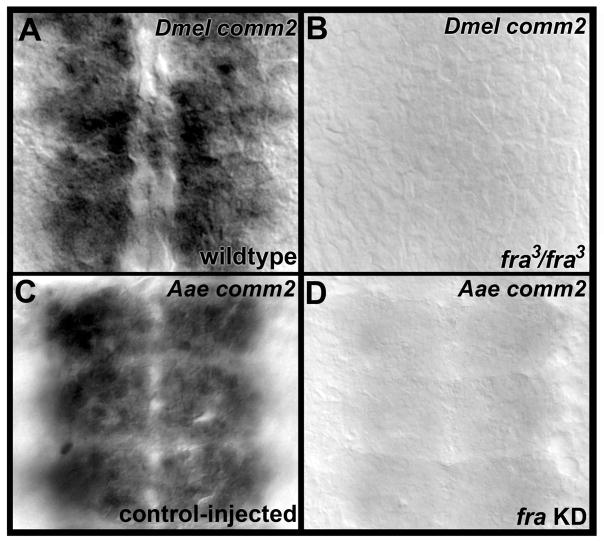

Loss of frazzled function results in loss of comm2 expression in D. melanogaster and A. aegypti

In previous studies, we noted that the A. aegypti fra knockdown phenotype, in which both the anterior and posterior commissures were disrupted, resembles that of the D. melanogaster comm loss of function phenotype (Clemons et al., 2011). Here, we demonstrated that knockdown of Aae comm2 results in commissure loss (Fig. 5E, G, H, Table 2) which resembles the Aae fra loss of function phenotype (Clemons et al., 2011). Likewise, loss of D. melanogaster comm2 results in defective commissural axon guidance (Fig. 8B), and the D. melanogaster comm2 (Fig. 8B) and fra loss of function mutant nerve cord phenotypes (Kolodziej et al., 1996) are notably similar. We have performed microarray experiments in which global changes in gene expression resulting from gain and loss of Fra signaling were assessed in D. melanogaster (see Experimental Procedures for approach/accession information; the comprehensive results of these studies will be presented in their entirety elsewhere). These experiments demonstrated that loss of fra resulted in a −0.10 log2 fold decrease in comm2 expression, while activation of Net-Fra signaling resulted in a 0.20 log2 fold increase in comm2 transcript levels. Although these fold changes were not statistically significant, these observations, when combined with the notable similarity of the fra and comm2 mutant phenotypes in both D. melanogaster and A. aegypti, suggested that comm2 expression levels may change in response to Fra signaling. Such a phenomenon has been described in relation to the Drosophila comm gene, the expression of which decreases in Drosophila fra mutants (Yang et al., 2009). Thus, comm2 transcript levels were assessed in fra[3] loss of function D. melanogaster embryos through whole-mount in situ hybridization. These experiments demonstrated that loss of fra function results in substantial loss of comm2 expression in the developing nerve cord (Fig. 9B, n=36). These results suggest that Fra downregulates repulsion in commissural axons that are being guided to the midline by regulating not only comm, but also comm2 levels. Thus, in addition to mediating the response of Netrin attractive cues secreted from the midline, Fra signaling also downregulates responses to repulsive Slit-Robo cues by promoting high levels of both Comm and Comm2.

Fig. 9. Loss of fra function results in decreased comm2 transcripts.

Loss of fra function results in decreased comm2 transcript levels in both D. melanogaster (B) and A. aegypti (D). A wild-type D. melanogaster embryo (A) and control-injected A. aegypti embryo (B) are included for comparison. Filleted nerve cords of stage 13 D. melanogaster embryos (A, B) and 49 hour old A. aegypti embryos (C, D) in which the anterior ends are oriented upward are shown.

Assessment of comm2 expression in A. aegypti fra knockdown embryos (Fig. 9D) demonstrated that the ability of Fra signaling to regulate comm2 transcript levels is conserved between D. melanogaster and A. aegypti. Loss of comm2 nerve cord expression was observed in 85% of fra knockdown siRNA-injected mosquito embryos (n=105). Thus, regulation of comm family gene transcript levels by Fra is observed outside of Drosophila. These findings demonstrate that although some insects lack an apparent comm family ortholog, the function of Comm2 is generally well conserved between D. melanogaster and A. aegypti, as evidenced through the well conserved expression patterns of comm2 in A. aegypti (Figs. 3 and 4) and D. melanogaster (Figs. 6 and 7), the commissure loss phenotypes observed in the comm2 loss of function nerve cords of both species (Figs. 5,8, Tables 2,3), and the finding that comm2 levels are regulated by Fra signaling in both insects (Fig. 9).

Given that Comm2 plays an essential role in the developing D. melanogaster and A. aegypti nerve cord, it is interesting that A. gambiae and T. castaneum appear to lack a comm family gene (Behura et al., 2011; Evans and Bashaw, 2012). It is possible that genome sequencing gaps or the notably low level of amino acid conservation among Comm family proteins has hindered the identification of a comm family ortholog in these insects, and that they do possess a comm family gene that cannot be identified through sequence comparisons. Interestingly, although no comm family genes have yet been identified in vertebrates, RabGDI was recently found to regulate Robo1 surface expression levels in chick commissural axons (Philipp et al., 2012). These findings suggest that other proteins, perhaps even Rab GDI which has been described in insects (Ricard et al., 2001), may function to regulate Robo surface levels in animals which lack apparent Comm family proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sequence analyses

Mosquito comm orthologs were previously identified (Behura et al., 2011) from Biomart (Smedley et al., 2009) and Vectorbase (Lawson et al., 2009). The amino acid sequences of Comm family proteins were obtained from Vectorbase (Lawson et al., 2009) and Flybase (Tweedie et al., 2009). ClustalW (Chenna et al., 2003) was used for multiple sequence alignment. The phylogenetic tree was drawn using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987), and a bootstrap consensus tree was inferred from 1000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1992). The Poisson correction method (Zuckerkandl and Pauling, 1965) was used to compute evolutionary distances which correspond to the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using MEGA4 (Tamura et al., 2007). The pairwise distance between genes was also calculated using MEGA4. The local sequence alignments for constructing motif maps of CPIJ016285 and CPIJ017280 in comparison with D. melanogaster Comm2 (FBgn0041160) was based on Dayhoff weight matrices (Leontovich et al. 1993) implemented in the GeneBee program (Brodsky et al. 1995).

Mosquito Rearing, Egg Collection, and Fixation

A. aegypti Liverpool- IB12 (LVP-IB12) and C. quinquefasciatus Johannesburg (JHB) strains, which were utilized in the genome sequencing efforts (Nene et al., 2007; Arensburger et al., 2010), were used in these studies. Mosquitoes were reared as previously described (Clemons et al., 2010b), except that an artificial membrane blood feeding system was employed. Procedures for A. aegypti embryo fixation (Clemons et al., 2010c) have been described, and these methods were applied to both A. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus in this investigation. C. quinquefasciatus embryos were staged as previously described (Davis, 1967).

Drosophila Genetics

The following D. melanogaster mutant stocks were used in this investigation: comm2[MB01146] (Bloomington Stock Center, #23000), comm2[MI02284] (Bloomington Stock Center, #33190), Df(3L)BSC845 (Bloomington Stock Center, #27888), and fra[3] (Bloomington Stock Center #8813). Detailed information about these stocks is available at Flybase (Tweedie et al., 2009). In summary, comm2[MB01146] and comm2[MI02284] are transgenic insertion stocks in the comm2 locus produced by the Drosophila Gene Disruption Project that were derived by transposable element mobilization with the Dhyd\Minos-based constructs Mi{ET1} and Mi{MIC}, respectively (Metaxakis et al., 2005; Bellen et al., 2011). Levels of comm2 transcript were not observed to be reduced in either strain, as is typical for Minos-generated alleles (Metaxakis et al., 2005). However, genetic characterization of these mutations described herein indicates that they behave as amorphic comm2 alleles. Df(3L)BSC845 is a large deletion of cytogenic region 71E1 which covers sequences 3L:15,559,113 to 15,569,413 and results in the deletion of numerous genes, including comm2 (Cook et al., 2012).

In situ hybridization, Immunohistochemistry, and Imaging

Riboprobes (~500 bp in size) corresponding to the following genes were synthesized as described (Patel, 1996): Aae comm2 (AAEL007250), Cqu comm2 genes CPIJ016283, CPIJ016285, and CPIJ017280, and D. melanogaster comm2 (CG7554). A. aegypti in situ hybridization experiments were performed as discussed previously (Haugen et al., 2010), and this method was applied to C. quinquefasciatus. D. melanogaster in situ hybridization experiments were performed as described previously (Patel, 1996; VanZomeren-Dohm et al., 2008).

Immunohistochemistry was performed in A. aegypti using previously published methodology (Clemons et al., 2010d), and this protocol was applied to C. quinquefasciatus. Drosophila embryos were prepared and stained as described by Patel (Patel, 1994), who discusses the use of BP102 and anti-Even-skipped (Eve) 2B8 antibodies which he graciously provided. Anti-acetylated tubulin antibody was obtained from Zymed (San Francisco, CA). Anti-GFP antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies used in this investigation were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA). Use of GFP marked balancers permitted genotype scoring of Drosophila embryos in immunohistochemical assays.

Samples were imaged using a Zeiss Axioimager equipped with a Spot Flex camera or with a Zeiss LSM 710 Confocal Microscope. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop and Zeiss ZEN Software.

RNAi knockdown experiments

Knockdown of Aae comm2 was performed through embryonic microinjection of siRNAs corresponding to this gene as previously described in a protocol (Clemons et al., 2010a) which has been successfully utilized in three recent embryonic knockdown investigations (Clemons et al., 2011; Haugen et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2013). The following siRNAs corresponding to Ae. aeygpti comm2 were synthesized by Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (Lafayette, CO): siRNA-1 sense: CGCCAGUGAUUUCAACCUGUU and antisense: CAGGUUGAAAUCACUGGCGUU (corresponds to base pairs 265–283 of Aae comm2) and siRNA-2 sense: CGACCUUCGGUCAUCAAACUU and antisense: GUUUGAUGACCGAAGGUCGUU (corresponds to base pairs 677–695 of Aae comm2). Previously described control siRNA (Nguyen et al., 2013) was used in these experiments; BLAST searches have confirmed that this siRNA does not have any known targets in the A. aegypti genome. For nerve cord phenotype assessments, at least eight replicate experiments were performed with each siRNA. Knockdown of Aae comm2 was confirmed through in situ hybridization experiments in two separate replicate experiments. Knockdown of Aae fra was performed as previously described in two separate replicate experiments (Clemons et al., 2011).

Microarray experiments

Two complementary microarray experiments were used to assess the impacts of Fra signaling on global gene expression. In the first experiment, global gene expression profiles for stage 13 fra[3]/fra[3] mutant Drosophila vs. wild-type embryos were compared. Four replicates, each with 10 embryos for each condition (fra[3] mutant or wild-type) were prepared. The second experiment examined effects of activated NetA-Fra overexpression in the third instar wing imaginal disc. GFP-marked NetA+Fra overexpression wing discs were prepared as previously described (Flannery et al., 2010), and age matched wild type discs with GFP clones were used as controls. Four replicates with 15 discs for each condition (NetA+Fra or wild-type) were prepared. For each of the two microarray experiments, total RNA was isolated using Trizol LS Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was quantified by OD260, and RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

RNA samples were sent to the University of Notre Dame Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facility which performed hybridization experiments using the Affymetrix GeneChip Drosophila Genome 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). RNA samples were processed and hybridized using the GeneChip 3′IVT Express kit (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, reverse transcriptase and an oligo(dT) primer were used to synthesize first-strand cDNA. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA polymerase. Biotin-modified amplified RNA (aRNA) was generated through in vitro transcription. The aRNA was purified, fragmented, and then hybridized in a GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640 at 45° C for 16 hours. Finally, the microarrays were washed and stained in a GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 and scanned in a GeneChip 3000 7G scanner. Microarray data pre-processing and normalization were performed using the Bioconductor packages in R. Microarray data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers GSE47112 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE47112, fra loss of function study) and GSE47113 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE47113; Net-Fra activation study).

Key Findings.

The vector mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus possess commissureless2 (comm2) genes (one and three, respectively) that are expressed by commissural axons during embryonic nerve cord development.

Knockdown of A. aegypti commissureless2 (Aae comm2), the single comm family ortholog in A. aegypti, results in a commissureless phenotype that phenocopies the frazzled (fra) loss of function phenotype in this species.

Mutation of D. melanogaster comm2, an ortholog of Aae comm2, also results in a commissureless phenotype which bears resemblance to the fra loss of function mutant.

Loss of Frazzled signaling in A. aegypti or D. melanogaster results in decreased comm2 expression, suggesting that Comm2 functions to mediate the conserved ability of Fra to downregulate repulsion in precrossing commissural axons of both species.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsors: NIH/NIAID Award R01-AI081795

University of Notre Dame Genomics and Bioinformatics Pilot Project Award

We are grateful to Ping Le who assisted with riboprobe preparation, as well as Charles Tessier and Lucy Shi who assisted with the Drosophila genetic crosses. We are grateful to Brent Harker for his assistance with the microarray experiments. Thanks to members of the lab for their advice and comments on the manuscript. M.D.S. and D.W.S. were funded by the National Institutes of Health. M.D.S., J.T., and E.Z. were funded by a University of Notre Dame Genomics and Bioinformatics Pilot Project Award.

References

- Arensburger P, Megy K, Waterhouse RM, Abrudan J, Amedeo P, Antelo B, Bartholomay L, Bidwell S, Caler E, Camara F, Campbell CL, Campbell KS, Casola C, Castro MT, Chandramouliswaran I, Chapman SB, Christley S, Costas J, Eisenstadt E, Feschotte C, Fraser-Liggett C, Guigo R, Haas B, Hammond M, Hansson BS, Hemingway J, Hill SR, Howarth C, Ignell R, Kennedy RC, Kodira CD, Lobo NF, Mao C, Mayhew G, Michel K, Mori A, Liu N, Naveira H, Nene V, Nguyen N, Pearson MD, Pritham EJ, Puiu D, Qi Y, Ranson H, Ribeiro JM, Roberston HM, Severson DW, Shumway M, Stanke M, Strausberg RL, Sun C, Sutton G, Tu ZJ, Tubio JM, Unger MF, Vanlandingham DL, Vilella AJ, White O, White JR, Wondji CS, Wortman J, Zdobnov EM, Birren B, Christensen BM, Collins FH, Cornel A, Dimopoulos G, Hannick LI, Higgs S, Lanzaro GC, Lawson D, Lee NH, Muskavitch MA, Raikhel AS, Atkinson PW. Sequencing of Culex quinquefasciatus establishes a platform for mosquito comparative genomics. Science. 2010;330:86–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1191864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behura SK, Haugen M, Flannery E, Sarro J, Tessier CR, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. Comparative genomic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster and vector mosquito developmental genes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen, et al. The Drosophila gene disruption project: progress using transposons with distinctive site specificities. Genetics. 2011;188(3):731–743. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.126995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y-J. Dissertation. The Ohio State University; 2003. Function of commissureless and related genes in Drosophila neural development. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons A, Haugen M, Severson D, Duman-Scheel M. Functional analysis of genes in Aedes aegypti embryos. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010a;2010:2010. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5511. pdb prot5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons A, Mori A, Haugen M, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010b. Culturing and egg collection of Aedes aegypti. 2010:pdb prot5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons A, Haugen M, Flannery E, Kast K, Jacowski C, Severson D, Duman-Scheel M. Fixation and preparation of developing tissues from Aedes aegypti. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010c;2010:2010. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5508. pdb prot5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons A, Flannery E, Kast K, Severson D, Duman-Scheel M. Immunohistochemical analysis of protein expression during Aedes aegypti development. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010d doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5510. 2010:pdb prot5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons A, Haugen M, Le C, Mori A, Tomchaney M, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. siRNA-mediated gene targeting in Aedes aegypti embryos reveals that frazzled regulates vector mosquito CNS development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RK, Christensen SJ, Deal JA, Coburn RA, Deal ME, Gresens JM, Kaufman TC, Cook KR. The generation of chromosomal deletions to provide extensive coverage and subdivision of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Biol. 2012;13(3):R21. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-r21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C. A comparative study of larval embryogenesis in the mosquito Culex fatigans wiedemann (diptera: culicidae) and the sheep-fly Lucilia sericata meigen (diptera: calliphoridae) Australian Journal of Zoology. 1967;15:547–579. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Science. 2002;298:1959–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ, Gilestro GF. Regulation of commissural axon pathfinding by slit and its Robo receptors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:651–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman-Scheel M, Patel NH. Analysis of molecular marker expression reveals neuronal homology in distantly related arthropods. Development. 1999;126:2327–2334. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans TA, Bashaw GJ. Slit/Robo-mediated axon guidance in Tribolium and Drosophila: divergent genetic programs build insect nervous systems. Dev Biol. 2012;363:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Estimating effective population size from samples of sequences: a bootstrap Monte Carlo integration method. Genet Res. 1992;60:209–220. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300030962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery E, Vanzomeren-Dohm A, Beach P, Holland WS, Duman-Scheel M. Induction of cellular growth by the axon guidance regulators netrin A and semaphorin-1a. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:473–484. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen M, Flannery E, Tomchaney M, Mori A, Behura SK, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. Semaphorin-1a is required for Aedes aegypti embryonic nerve cord development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen M, Tomchaney M, Kast K, Flannery E, Clemons A, Jacowski C, Simanton Holland W, Le C, Severson D, Duman-Scheel M. Whole-mount in situ hybridization for analysis of gene expression during Aedes aegypti development. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2010 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5509. pdb prot5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keleman K, Rajagopalan S, Cleppien D, Teis D, Paiha K, Huber LA, Technau GM, Dickson BJ. Comm sorts robo to control axon guidance at the Drosophila midline. Cell. 2002;110:415–427. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00901-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keleman K, Ribeiro C, Dickson BJ. Comm function in commissural axon guidance: cell-autonomous sorting of Robo in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nn1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96:785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej PA, Timpe LC, Mitchell KJ, Fried SR, Goodman CS, Jan LY, Jan YN. frazzled encodes a Drosophila member of the DCC immunoglobulin subfamily and is required for CNS and motor axon guidance. Cell. 1996;87:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriventseva EV, Rahman N, Espinosa O, Zdobnov EM. OrthoDB: the hierarchical catalog of eukaryotic orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D271–275. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson D, Arensburger P, Atkinson P, Besansky NJ, Bruggner RV, Butler R, Campbell KS, Christophides GK, Christley S, Dialynas E, Hammond M, Hill CA, Konopinski N, Lobo NF, MacCallum RM, Madey G, Megy K, Meyer J, Redmond S, Severson DW, Stinson EO, Topalis P, Birney E, Gelbart WM, Kafatos FC, Louis C, Collins FH. VectorBase: a data resource for invertebrate vector genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D583–587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern VL, Seeger MA. Mosaic analysis reveals a cell-autonomous, neuronal requirement for Commissureless in the Drosophila CNS. Dev Genes Evol. 2003;213:500–504. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metaxakis A, Oehler S, Kliakis A, Savakis C. Minos as a genetic and genomic tool in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2005;171(2):571–581. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.041848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nene V, Wortman JR, Lawson D, Haas B, Kodira C, et al. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316:1718–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C, Andrews E, Le C, Sun L, Annan Z, Clemons A, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. Functional genetic characterization of salivary gland development in Aedes aegypti. Evodevo. 2013;4:9. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N. In situ hybridization to whole mount Drosophila embryos. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1996. pp. 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH. Imaging neuronal subsets and other cell types in whole-mount Drosophila embryos and larvae using antibody probes. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:445–487. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp M, Niederkofler V, Debrunner M, Alther T, Kunz B, Stoeckli ET. RabGDI controls axonal midline crossing by regulating Robo1 surface expression. Neural Dev. 2012;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard CS, Jakubowski JM, Verbsky JW, Barbieri MA, Lewis WM, Fernandez GE, Vogel M, Tsou C, Prasad V, Stahl PD, Waksman G, Cheney CM. Drosophila rab GDI mutants disrupt development but have normal Rab membrane extraction. Genesis. 2001;31:17–29. doi: 10.1002/gene.10000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M, Tear G, Ferres-Marco D, Goodman CS. Mutations affecting growth cone guidance in Drosophila: genes necessary for guidance toward or away from the midline. Neuron. 1993;10:409–426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90330-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley D, Haider S, Ballester B, Holland R, London D, Thorisson G, Kasprzyk A. BioMart--biological queries made easy. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Tessier-Lavigne M. Hierarchical organization of guidance receptors: silencing of netrin attraction by slit through a Robo/DCC receptor complex. Science. 2001;291:1928–1938. doi: 10.1126/science.1058445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tear G, Harris R, Sutaria S, Kilomanski K, Goodman CS, Seeger MA. commissureless controls growth cone guidance across the CNS midline in Drosophila and encodes a novel membrane protein. Neuron. 1996;16:501–514. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie S, Ashburner M, Falls K, Leyland P, McQuilton P, Marygold S, Millburn G, Osumi-Sutherland D, Schroeder A, Seal R, Zhang H. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D555–559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanZomeren-Dohm A, Flannery E, Duman-Scheel M. Whole-mount in situ hybridization detection of mRNA in GFP-marked Drosophila imaginal disc mosaic clones. Fly (Austin) 2008;2:323–325. doi: 10.4161/fly.7230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf B, Seeger MA, Chiba A. Commissureless endocytosis is correlated with initiation of neuromuscular synaptogenesis. Development. 1998;125:3853–3863. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Garbe DS, Bashaw GJ. A frazzled/DCC-dependent transcriptional switch regulates midline axon guidance. Science. 2009;324:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1171320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in the proteins. In: Vogel VBaHJ., editor. Evolving Genes and Proteins. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 97–166. [Google Scholar]