Abstract

The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence, size, shape, and location of torus palatinus (TP) and torus mandibularis (TM), and to assess their sex-related and age-related differences in the Malay population. Sixty-five subjects were assessed for the presence of both tori at the School of Dental Sciences University Sains Malaysia. The prevalence of TP was 38–63% and that of TM was 1–10%. TP was frequently more common in females than males (90.9% versus 9.1%; P < 0.05) and was frequently found in medium sizes, spindle shaped, and was often located at the combined premolar to molar areas. The prevalence of TM was not significantly different in males and females (33.3% versus 66.7%; P = 0.523), occurred most commonly in bilateral multiple form, and was often located at the canine to premolar area.

Keywords: Torus mandibularis, torus palatinus, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Torus palatinus (TP) and torus mandibularis (TM) are two of the most common intraoral exostoses. Other types of exostoses, affecting the palatal aspect of the maxilla (palatal exostoses) or the buccal aspects of the jaws (buccal exostoses), are less commonly encountered. TP is a sessile nodule of the bone found only in the midline of the hard palate, while TM is a bony protuberance located in the lingual aspect of the mandible, commonly at the canine and premolar areas.[1] Although the tori are not pathologically significant, they may obscure radiographic details of maxillary sinuses and lower premolars. They also interfere with the construction and function of removable dentures, as well as oral function and movement.[1] The prevalence of tori varies widely in different populations, ranging from 0.4% to 66.5% for TP[2] and 0.5% to 63.4% for TM.[2] Racial differences appear significant, with high prevalence in the Asian and Eskimo population.[3] Differences in the prevalence between genders has also been reported. Most authors reported that TP was more frequent in females, while TM affected males more than females.[4] The postulated causes include genetic factors[4] that play a leading role in its occurrence, environmental factors,[5] hyper—function, and continuous growth. The present study was done to determine the prevalence, size, shape, and location of the tori and to investigate the sex and age relation of TP and TM in the Malay population of Malaysians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our subjects consisted of 65 Malays that included patients from dental outpatient clinic, students, staff, and dental auxiliaries of The School of Dentistry, University Sains Malaysia, Kubang Kerian Kelantan, Malaysia. The subjects were grouped into six different age groups: 13–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and 60 years and above. The presence of both tori was examined by clinical inspection and palpation performed by one examiner. Questionable tori were recorded as not present. For the presence of tori, study casts were made using alginate impression material for assessment of the size, shape, and location of the tori. For the size of TP, it was measured at the highest elevation of the outgrowth, using Vernier calipers (OEM,CHINA) with the output to the nearest 0.01 mm. The average size of the tori was graded according to the classification of Reichart et al.,[4] as follows: small (<3mm), medium (3–6 mm) and large (>6 mm). The location of TP was classified as premolar, molar, premolar to molar, incisor to premolar, and incisor to molar areas. TM was identified by the number of nodes and their placement, and was divided into four categories: bilateral single, bilateral multiple, unilateral single, and unilateral multiple, as previously described by Kolas et al.[6] Location of TM was recorded as incisor, incisor to canine, incisor to premolar, incisor to molar, incisor and premolar, canine, and canine to premolar. The statistical package for social science (version 11.0) was used for analysis. The Chi-square test was used to test for group differences and sex and age correlation with the prevalence of TP and TM. Difference between groups with P <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Prevalence

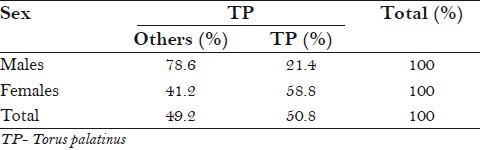

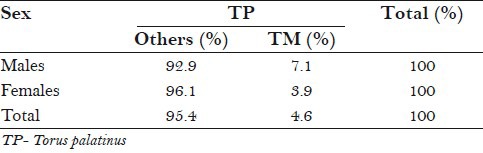

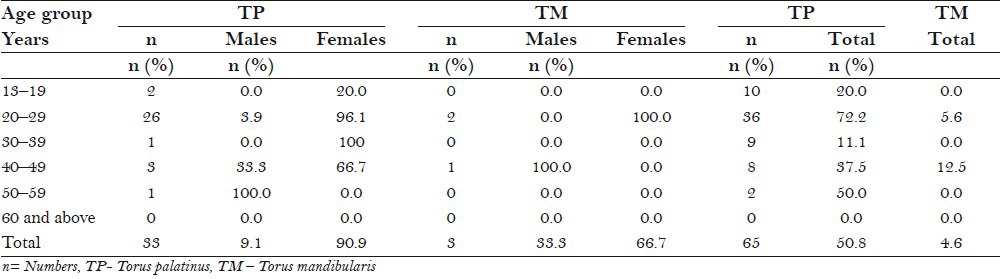

TP and TM were observed in 50.8% and 4.6% respectively, for the total subjects [Tables 1 and 2]. We are 95% sure that the prevalence of TP in population will be between 38% and 68%, and the prevalence of TM in population will be between 1% and 10%. TP was found to be significantly higher in females than in males (90.9% versus 9.1%; P < 0.05%), while TM was found to be not significantly different either in males or females (33.3% versus 66.7%; P = 0.523) [Table 3].

Table 1.

Distribution of TP in relation to sexes

Table 2.

Distribution of TM in relation to sexes

Table 3.

The distribution of TP and TM in relation to age and sexes

Size, shape and location of TP

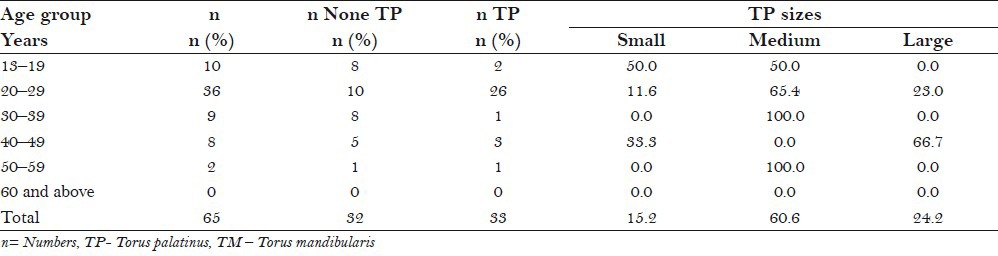

Out of 33 subjects with TP studied, we found that most were medium in size, followed by large in size, and the least was small in size (60.6% for medium in size). The age and sex differences in the distribution pattern of TP according to size were statistically not significantly different (P = 1.000). The age groups of subjects that mostly have medium size of TP were 20–29 years old [Table 4]. Table 5 shows distribution of TP in relation to age group and shapes. Spindle shape of TP was the most frequently observed, followed by lobular, and the least was nodular. There was a relationship between shape and size of TP (P < 0.05). Most spindle-shaped TP were in medium size, and most of the spindle-shaped TP were in 20–29 years’ old age group. Table 6 shows the distribution of TP in relation to location and age group. The most common location for TP was in the premolar area and the least was in the incisor to molar area. Most TP in the 20–29 years’ age group were located in the premolar area. There was an association between age and location of TP (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

The distribution of TP in relation to sizes and age groups

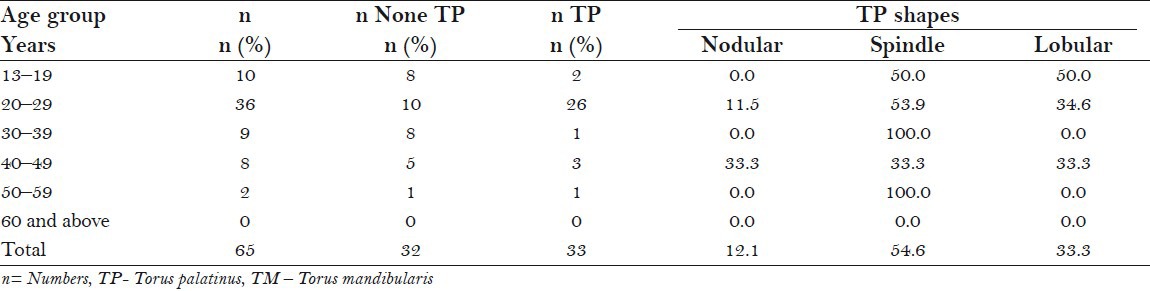

Table 5.

The distribution of TP in relation to shapes and age groups

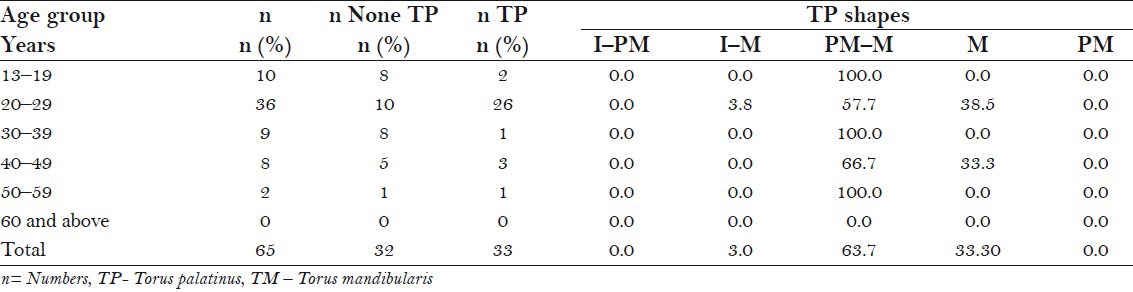

Table 6.

The distribution of TP in relation to location and age groups

Shape and location of TM

Table 7 shows the distribution of TM in relation to the number of nodes and placement with age groups. Most TM were bilateral multiple (66.7%) and followed by bilateral single (33.3%). Bilateral multiple TM was found in symmetrical pattern. The most common location of TM was in the canine to premolar area (66.7%) followed by incisor to premolar area (33.3%) [Table 8].

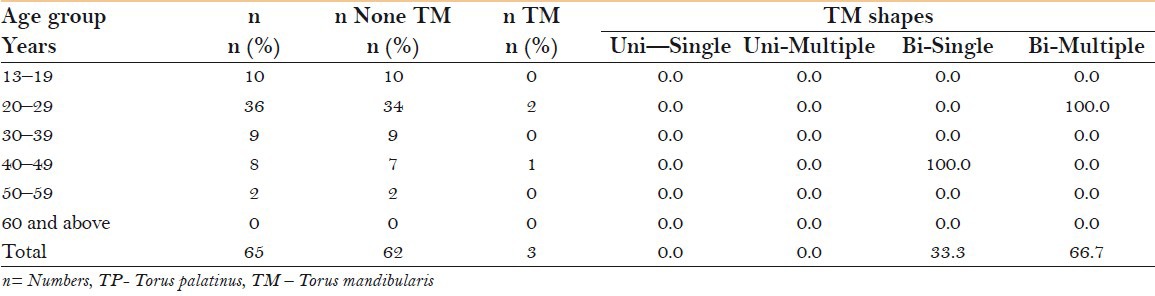

Table 7.

The distribution of TM in relation to shapes and age groups

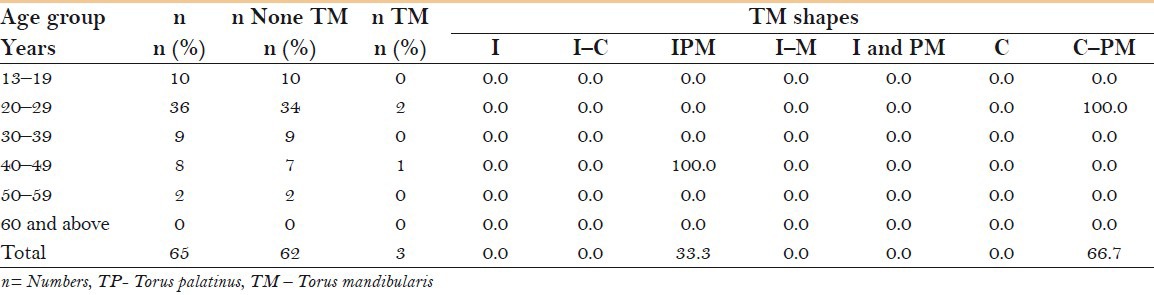

Table 8.

The distribution of TM in relation to location and age groups

DISCUSSION

The results of this study are in agreement with most of the previous studies that TP is more common in females than in males.[3,5,6] Other studies also reveal that TM is more common in males than females.[2,4,5] This is not in accordance with the results of this study. It can occur in both sexes, not particularly high in males only. Results from a previous study in Thais[1] suggest that the occurrence of TP is a sex-related phenomenon, but not for TM. Haugen[5] stated that there was no obvious explanation for the gender differences but suggests genetics as a responsible factor. According to Alvesalo et al.,[7] who studied TM in females with Turner syndrome (45, X), it was suggested that sexual dimorphism in the manifestation of TM might result from the effect of the Y chromosome on the growth, occurrence, expression, and timing of development of TM. Eggen and Natvig[8] reported a similar result in Norwegians and summarized that decreased occurrence of TM among individuals over 50 years of age was related to the number of remaining teeth. Sonier et al.[9] reported that the prevalence of TM was directly related to the presence of teeth. Most of our subjects in the age group of 50 and above were partially edentulous. So it may show that functional influences may be a contributing factor to the occurrence of the tori. Our result shows that the prevalence of tori was mostly in the second decade life, which is in accordance with the previous report of King and Moore[10] stated that, no great differences in the percentage of tor iwhich affected below the age of 30 and assumed that there was little or no further growth of tori after the age of 30. We found that subjects in the 20–29 age group were more likely to have medium size of TP than those in the younger age group. This result supports the association between age and continued growth of tori as reported by Topazian and Mullen.[11] 10 study showed that females had higher frequency of TP and tended to have more medium in size TP than males, which is in accordance with the study in Thais.[1] In a Singaporean study, Chew and Tan[12] reported that 37% of TP present at two thirds of the palate and concluded that the Chinese tended to have large tori. Most of the TP in our study was in the premolar to molar area like the previous study in Thais.[1] Nodular TP was found with the least frequency. Some authors have reported that lobular TP was the rarest type. In the study in Thais,[1] flat TP was found to be the rarest type, and was in contrast with other studies in which this type of TP was predominant. For TM, we observed more bilateral than unilateral, with symmetrical occurrence. These studies are in accordance with most of the studies[1,4,5,6] We also found that most TM were located at the canine to premolar area as in the previous reports.[1] Responding during life to environmental and functional factors that act in a complicated interplay with genetic factors,[5] further studies are also needed to compare the prevalence of tori among races in Malaysia.

CONCLUSION

The results of this pilot study need to be further studied to support the hypothesis that the occurrence of torus can be considered as a dynamic phenomenon, responding during life to environmental and functional factors that act in a complicated interplay with genetic factors. Further studies are also needed to compare the prevalence of tori among races in Malaysia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wandee A, Aree J. Somporn Torus Palatinus and Torus Mandibularis in a Thai population. Sci Asia. 2002:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hrdlicka A. Mandibular and Maxillary hyperostosis. Am J Anthropol. 1940;27:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo JK. Torus Palatinus. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1950;8:81–111. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330080114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichart PA, Neuhaus F, Sookasem M. Prevalence of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis in Germans and Thai. Community Dent Oral Epidemio. 1988;16:61–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haugen LK. Palatine and mandibular tori, A morphologic study in the current Norwegian population. Acta Odontol Scand. 1992;50:65–77. doi: 10.3109/00016359209012748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolas S, Halperin V, Jerreris K, Huddelston S. Robinson HBG the occurrence of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis in 2,478 dental patients. Oral Surg. 1953;6:1134–14. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(53)90225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvesalo L, Mayhall JT, Varella J. Torus mandibularis in 45, X females Turners syndrome. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1996;101:145–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199610)101:2<145::AID-AJPA2>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggen S, Natvig B. Variations in torus mandibularis prevalence in Norway, a statistical analysis using logistic regression. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:32–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonner KR, Horning GM, Cohen ME. Palatal tubercles, palatal tori and mandibular tori: prevalence and anatomical features in U.S population. J Periodontal. 1999;70:329–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King DR, Moore GE. The prevalence pf Torus palatinus. J Oral Med. 1971;26:113–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topazian DS, Mullen FR. Continued growth of a Torus palatinus. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:845–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chew CL, Tan PH. Torus Palatinus A clinical study. Aust Dent J. 1984;29:245–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1984.tb06066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]