Abstract

Objectives.

Despite increases in social support following widowhood, loneliness is among the most frequently reported challenges of bereavement. This analysis explores the dynamic relationship between social support and loneliness among recently bereaved older adults.

Methods.

Using longitudinal data from “Living After Loss” (n = 328), latent growth curve modeling was used to estimate changes in loneliness and social support during the first year and a half of bereavement among older adults aged 50+.

Results.

Both loneliness and social support declined over the first year and a half of bereavement. Greater social support was associated with lower levels of loneliness overall, but the receipt of social support did not modify one’s expression of loneliness over time. Loneliness was more highly correlated with support from friends than family. Together, social support from both friends and family accounted for 36% of the total variance in loneliness.

Discussion.

There is conceptual and empirical overlap between the concepts of loneliness and social support, but results suggest that loneliness following widowhood cannot be remedied by interventions aimed only at increasing social support. Social support, especially that from friends, appears to be most effective if it is readily accessible and allows the newly bereaved an opportunity to express him/herself.

Key Words: Bereavement, Loneliness, Social support, Widowhood.

Spousal bereavement is regarded as one of the most distressing experiences of adulthood (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). As a result, widowhood is often accompanied by poor mental health outcomes such as increased grief and depressive symptoms (Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2006). Loneliness is another common response reported by widowed persons (Beal, 2006; Pinquart, 2003; Savikko, Routasalo, Tilvis, & Pitkälä, 2010). In fact, one study found that nearly 70% of older widow(er)s identified loneliness as the single most difficult aspect to cope with on a day-to-day basis (Lund, 1989).

The term loneliness is often equated with social isolation or social participation (Ben-Zur, 2012). However, seminal work by Moustakas (1961) and Weiss (1973) attempted to distinguish loneliness from these constructs by defining it as the cognitive or psychological appraisal of social relationships and activities (Holmén & Furukawa, 2002). For example, loneliness has been conceptualized as the lack of “meaningful” social relationships (Fees, Martin, & Poon, 1999) or “incongruence” between actual and desired levels of social interaction (Perlman & Peplau, 1982). Most definitions of loneliness also typically stress the subjective or individualistic nature of the concept (Rokach, 2011), recognizing that two people with similar social resources may have very different subjective experiences of loneliness. For example, one might have very little social participation or a relatively small social network but be satisfied with the quality and frequency of those interactions and therefore not experience much loneliness. Others may have much larger social networks and more engagement in social activities, but lack meaningful connections with these people and activities, increasing their likelihood for loneliness (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2001). Although loneliness is conceptually tied to the magnitude of one’s social network or frequency of social participation, an expression of loneliness depends on how that individual subjectively perceives the quality of those relationships and how satisfied he/she is with the types of support received from those relationships (Rokach, 2011). Throughout this article, the term “social support” refers to a property of one’s social networks, whereas “loneliness” is a state of mind that encapsulates the cognitive or emotional appraisal of one’s social resources. This allows us to distinguish between “being” alone and “feeling” alone.

Some have argued that older adults, compared with younger persons, might be more susceptible to loneliness given the number of losses they encounter through age-related transitions such as retirement, empty nest, deaths of friends and family, disability, and illness diagnosis. These types of losses typically affect social connectedness or ability to participate in social network activities, perhaps increasing loneliness among older adults (Blazer, 2002; Fees et al., 1999). In particular, the death of a spouse/partner signifies the loss of a significant attachment figure that, likely, provided a meaningful and intimate source of social support (Pinquart, 2003). Therefore, it is not surprising that past studies have found that marital status, particularly widowhood, is among the strongest predictors of loneliness (Beal, 2006; Savikko et al., 2010) and that loneliness is among the most outcomes associated with widowhood (Lund, 1989).

Socio-emotional selectivity theory states that, in general, older adults may not desire as much social stimulation and interaction as younger persons do and that they tend to select the most valuable relationships to invest in (Adams, Sanders, & Auth, 2004; Carstensen, 1991). Within the context of widowhood, previous social relationships may become unavailable or less available to the surviving spouse—for example, those relationships tied to the spouse or to the couple—thus, widowhood typically necessitates a selectivity and readjustment process, whereby the surviving spouse must renegotiate and redefine social relationships that are deemed most important and meaningful. Given this inevitable readjustment process, we hypothesize that although older adults may face greater risk for loneliness at the time of widowhood, because of the significant and meaningful attachment that was lost when the spouse died, the feelings of loneliness may lessen over time as the widowed person realigns social networks and expectations to reflect the new status as a widow or widowers.

Such hypotheses regarding changes in loneliness require longitudinal data. To date, very little research has looked at loneliness as a dynamic outcome (Cacioppo, Elizabeth, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006), and the need for longitudinal analysis of outcomes has been repeatedly called for in the bereavement literature (Stroebe, Stroebe, Abakoumkin, & Schut, 1996). Thus, the first aim of this study is to explore the dynamics of loneliness within the context of spousal bereavement. By separating social support and loneliness as distinct concepts, this study offers a second and equally important aim: whether social support can modify the experience of loneliness over time for older widowed spouses.

Widowed persons often receive an outpouring of support during the months following the death of a spouse. Perhaps in response to the anticipated feelings of loneliness that widowed persons typically experience, friends and family often try to fill some of the void left by the passing of the spouse/partner. They do this initially by participating in funeral and memorial services (Lopata, 1996) but also may maintain increased contact through additional visits or phone calls to provide support, camaraderie, diversion, and general checking-in (Donnelly & Hinterlong, 2010; Utz, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2002). One study found that the increased support from friends and family declined over time but stayed elevated up to 4 years after the death (Utz et al., 2002). Another study suggested that this outpouring of social support is mostly confined to the weeks and months following the death or the “crisis” period following the loss and including the funeral services (Scott et al., 2007).

A naive hypothesis would assume that greater social support would be associated with less loneliness (Ben-Zur, 2012). Although this hypothesis is likely correct, this study is more concerned about the dynamics between social support and loneliness. For example, within a widowed sample, does loneliness wax, as the crisis support wanes? Do reports of loneliness decrease over time, perhaps as the widowed person renegotiates and selects the most meaningful social relations following the loss of their spouse? If one is satisfied with their receipt of social support, regardless of whether it is objectively small or big, is he/she less likely to be lonely? This study attempts to explore the longitudinal dynamics between social support and loneliness, trying to explain how widowed persons cope with the changes in social support, and how those changes are reflected in their expressions of loneliness over time.

Finally, this study explores whether particular types of social support may be more or less central to feelings of loneliness over time. To this end, we have separated social support received from friends versus family members. Extant literature has defined the specific types of support roles friends versus family provide for older adults (Barker, 2002). Underlying this distinction is the fact that friendships are typically built upon mutual choice, shared interest, and affection, whereas familial relations are given, usually by blood or marriage, and do not require the same level of mutual commitment in terms of establishment or maintenance of the relationship as friendships typically require (Lee & Ishii-Kuntz, 1987). Furthermore, many family relationships are intergenerational—for example, parent–child relationships; attitudinal differences separating the generations may make such relationships less meaningful than friendships with similarly born cohort peers (Shapiro, 2004). In addition, increased contact with family members following widowhood is often in the context of estate settlement or to address the financial, instrumental, or emotional needs of the surviving spouse; these types of interactions can be contentious and may feel more like an obligation than a choice (Benkel, Wijk, & Molander, 2009). On the other hand, increased support from friends following bereavement may provide a socially desirable diversion for the widowed persons, because friendships tend to be formed on mutual interest and choice. Given the potential differences in how and why families and friends interact with the newly bereaved, we hypothesize that social support from friends may play a more significant role in determining one’s level of loneliness than the support provided by family members. This hypothesis is framed within the cognitive discrepancy model introduced earlier to distinguish the difference between social support and loneliness.

The Current Study

The overarching goal of this analysis is to explore the conceptual and empirical difference between loneliness and social support or as the title of the article suggests, “feeling alone” versus “being alone.” Spousal bereavement is an ideal context to study the dynamics of loneliness and social support, given the documented changes in social support that follow the death of a spouse (Utz et al., 2002) and the common reports of loneliness among bereaved persons (Lund, 1989). Because both constructs—loneliness and social support—vary by common demographic characteristics such as gender, resources of the individual such as his/her health, and specific circumstances associated with the death or the unique preferences or coping styles of the individual (Rokach, 2011; Weiss, 1973), such an analysis would benefit from a richly contextualized data set that was able to explore possible confounding relationships between social support, loneliness, and other relevant covariates that are commonly correlated with both constructs.

Specifically, we used a repeated measures sample of newly bereaved older spouses with a rich set of covariates to identify (a) how loneliness changed over time, and (b) the extent to which social support, as well as other covariates that commonly associated with social support and loneliness, might explain variations in loneliness. These analyses consider social support from friends versus family separately to evaluate what role friends and family members play in supporting newly bereaved persons. It is important to understand the dynamic and interrelated processes of social support and loneliness for this population, as it may provide practical insight into what types of support interventions may be effective in reducing loneliness among the newly bereaved.

Method

Data

Data come from “Living After Loss” (LAL), a longitudinal study of older bereaved spouses/partners. Participants completed questionnaires at approximately three (baseline, 01), six (02), nine (03), and fifteen (04) months after the spouse’s death. All data were collected between February 2005 and June 2009. In between the baseline and 02 data collections, participants completed one of two interventions, each consisting of a 14-week facilitator-led support group (Lund, Caserta, Utz, & de Vries, 2010b). One was a traditional support group focusing exclusively on the emotional needs of the bereaved person. The second was theoretically based on the “dual process model of coping” (Stroebe & Schut, 2010), which states that bereaved persons should oscillate between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented coping tasks; this support group included traditional facilitator-led discussions about loss and grief, as well as guest speakers who provided information and training that might help the bereaved readjust their daily life (for instance, household repairs, nutrition, finances, home safety). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two intervention conditions. Exposure to one intervention condition versus the other did not affect any of the substantive results for this analysis; thus, the two study conditions were combined, providing a longitudinal sample of older bereaved persons from 2 months to 18 months postloss (Utz, Caserta, & Lund, 2012).

Sample

The LAL sample was restricted to persons older than 50 years and whose spouse/partner had died 2–6 months (M = 3.6) prior to completing the baseline questionnaire. Eligible participants were initially identified from vital statistic records maintained by two cities/counties in the western United States (Lund, Caserta, Utz, & Devries, 2010a). Female deaths were oversampled to ensure enough widowers in the analytic sample. Traumatic or violent deaths (e.g., suicides, homicides) were excluded because these deaths often elicit unique bereavement experiences that cannot be adequately addressed in a group-based intervention (Mitchell, Kim, Prigerson, & Mortimer-Stephens, 2004). The final sample size was 328.

Although the LAL study is based initially on a random sample of death records, participants likely represent a unique population of persons who were willing to participate in a 14-week support group, as well as complete the research aspect of the LAL study. It is estimated that 10%–42% of widowed persons receive support from an organized group or therapist during the early period of widowhood (Caserta, Utz, Lund, & de Vries, 2010; Levy & Derby, 1992). Of the 328 participants, 84% (n = 274) completed all four questionnaires, and more than 90% (n = 298) completed questionnaires for at least two time points. Exploratory analyses found that missing data, due to nonresponse and attrition, were random for all variables used in this analysis.

Measures

Loneliness.—

It was measured with the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, a well-accepted multi-item index of loneliness. The shortened scale used in this analysis summed 13 items that have the most predictive value among older samples (Russell, 1996). Examples include “How often do you feel that you are ‘in tune’ with people around you” and “How often do you feel isolated from others?” Each item was measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from never to always, resulting in a theoretical range of 13–52 for the combined factor score. Some items were reverse coded so the lowest values always represented the lowest levels of loneliness. This scale had high internal consistency, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 when assessed with the baseline LAL sample. A loneliness factor score was created for each of the 01, 02, 03, and 04 questionnaires, thus providing four repeated measures of loneliness spanning the first year and a half of widowhood.

Social support.—

It was measured with a series of questions capturing both the quantity and perceived quality of social network resources. As opposed to a simpler measure of network size, this multidimensional approach to measuring social support considers that individuals develop an internal standard or expectation against which they judge their interpersonal relationships: For example, some may be satisfied with the support they receive from a very small number of social connections, whereas others may have a large number of support persons but still feel like their support needs are not addressed (Perlman & Peplau, 1982). Although there is a subjective element included in this measurement of social support, it remains distinct from the measurement of loneliness, which focuses exclusively on feelings of isolation or connectedness.

Two separate factor scores were created to measure social support: one measuring support from “friends” and one measuring support from “family.” Each factor score included four indicators: size of the support network (how many?), frequency of contact (how often?), ease of contact, and satisfaction with the support received. For network size, respondents reported the number of persons they considered to be in their support networks (range: 0–250). Frequency, ease, and satisfaction were measured on 5-point Likert scales with 1 being the lowest score (e.g., least amount of contact, difficult access to support network, and most unsatisfactory relationships quality) and 5 being the highest score. Values for network size were not normally distributed; skewness scores were 6.611 for friends and 8.393 for family. Statistical transformations failed to yield normal results, so the frequency item was recoded into five quintiles coded 1 through 5, with 1 representing the fewest friends or family members (three or less) and 5 representing the most friends of family members (16 or more). The residuals of each individual item regressed on the others were normally distributed indicating multivariate normality, and there was no indication of problematic multicollinearity when the four indicators were combined into a single factor scores measuring social support.

These factor scores (“Social Support from Family”; “Social Support from Friends”) have a theoretical range from 4 to 20, with higher values indicating greater social support and lower values indicating less social support. Like the loneliness scale, these two scales were measured on each of the four questionnaires, providing repeated measures of social support during the first year and a half of widowhood.

Covariates.—

A series of covariates captured individual-level characteristics that are risk factors for loneliness, so ought to be controlled for in models predicting patterns of loneliness. These included (a) socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex, race, religion, living arrangements, and financial status; (b) health variables assessing both physical and mental health of the surviving spouse; (c) variables describing the context of the death (expected or not) and marital quality; and (d) features of the LAL study design are also controlled to show, for example, whether exposure to one support group versus the other affected the outcome loneliness. As mentioned previously, these latter variables were not significant in any analyses. Finally, a series of variables measuring unique aspects of social support such as whether the respondents feel they have an adequate opportunity to express themselves and whether there is a person with whom they can share their thoughts are explored in some analyses to pinpoint potential mechanisms through which social support may affect expressions of loneliness.

Analytic Plan

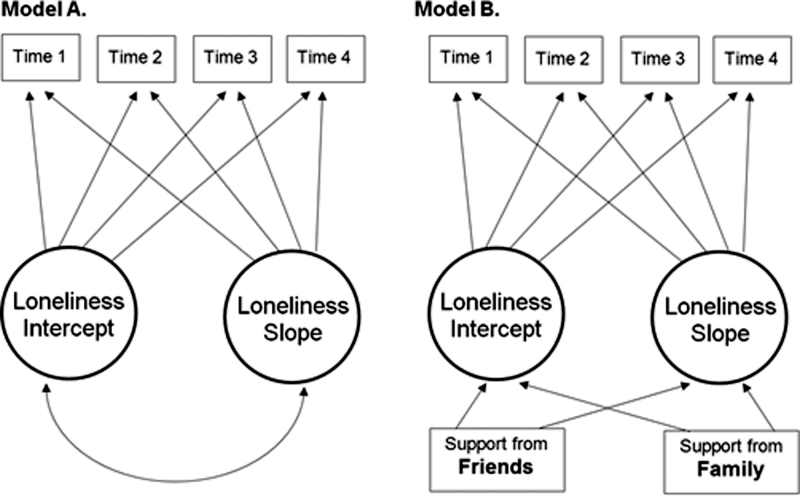

We used latent growth curve (LGC) modeling to estimate the longitudinal trajectory of loneliness and social support among recently bereaved persons. The initial two-factor model for loneliness, shown in Figure 1A, estimated the mean level of loneliness at approximately two months postloss (intercept mean) and tested for significant differences between people (intercept variance). It also estimated the average rate of change in loneliness over time (slope mean) and tested for significant intraperson differences in these trends (slope variance). This initial unconditional model was then expanded to explore which covariates were associated with both the slope and the intercept of loneliness. Figure 1B shows how social support from friends and social support from family may modify the intercept or slope of loneliness. Similar models were estimated to test the effects of all possible control variables. The LGC analyses were conducted using the Growth Curve Model plug-in available through AMOS 18. Final multiple regression models, using SPSS (18 PASW), were estimated to explore how much variation in loneliness was explained by social support and the various covariates explored.

Figure 1.

Two latent growth curve models predicting loneliness. Model A estimates the longitudinal trajectory of loneliness over time. Model B explores the covariates associated with loneliness over time. The version of Model B depicted here shows the role of the primary independent variables (i.e., social support from family and friends); similar models were estimated to explore how other covariates modified the intercept and slope of loneliness.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive patterns of within-subject and between-subject variations in both loneliness and social support among bereaved persons over the first year and a half of widowhood. In general, loneliness decreased over time (p < .001), as did the number of friends and family identified in the social support network (p < .01). Respondents reported a decline in visits from family members (p < .001), but the frequency of visits with friends remained unchanged over time. Similarly, there was no difference over time in the reported ease of contact or satisfaction with friend or family support. These descriptive analyses, using repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA), revealed considerable intersubject variation across all of the variables explored.

Table 1.

Average Loneliness and Social Support Indicators After Widowed

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–4 months | 5–7 months | 8–10 months | 14–16 months | ||

| Loneliness (scale, 13–52) | 26.4 | 25.7 | 25.6 | 24.7 | ***, + |

| Social support: friends | |||||

| Quantity (n) | 12.24 | 12.48 | 11.86 | 8.67 | ***, + |

| Frequency (1–5) | 3.56 | 3.51 | 3.44 | 3.48 | + |

| Ease (1–5) | 4.07 | 4.16 | 4.14 | 4.16 | + |

| Satisfaction (1–5) | 3.98 | 4.09 | 4.07 | 4.07 | + |

| Social support: family | |||||

| Quantity (n) | 11.50 | 10.97 | 10.43 | 9.46 | **, + |

| Frequency (1–5) | 3.94 | 3.84 | 3.80 | 3.72 | ***, + |

| Ease (1–5) | 4.33 | 4.40 | 4.29 | 4.39 | + |

| Satisfaction (1–5) | 4.16 | 4.22 | 4.19 | 4.15 | + |

Notes. Repeated measures analysis of variance tested for between-subject variation, as indicated by +p < .001. Repeated measures analysis of variance tested for within-subject change (linear assumption), as indicated by **p < .01 and ***p < .001.

The longitudinal patterns of loneliness suggested in Table 1 were confirmed using a two-factor LGC model, as depicted earlier in Figure 1A. Both linear and quadratic trends were explored, finding that the linear model produced far better statistical fit: linear: χ 2 (df = 8) = 8.66, p = .417; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .008; quadratic: χ 2 (df = 8) =16.065, p = .041; RMSEA = .058. Table 2 presents the results from the linear model. The significant coefficient for slope suggests that loneliness changed over the first year and a half of widowhood; it decreased over time (σ 2 = −.36, p < .001). This model also showed that a significant amount of the total variance in loneliness was attributed to between-subject variation (σ 2 = 28.79, p < .05), with very little coming from within-subject variation in slopes (σ 2 = .23, p = .11). In other words, loneliness decreased over time, with the change being largely consistent across people regardless of how much loneliness they initially reported. The nonsignificant covariance between intercept and slope (σ 2 = .13, p = .78) indicated that change in loneliness was not related to the amount of loneliness that a person experienced initially at time 01.

Table 2.

Change in Loneliness Scores Over Time, as Estimated by a Two-Factor Latent Growth Curve Model (Figure 1A)

| Unstandardized estimate | Standard error | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept mean | 26.23 | 0.34 | <.001 |

| Intercept variance | 28.79 | 2.90 | <.001 |

| Slope mean | −0.36 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Slope variance | 0.23 | 0.14 | .10 |

| Intercept–slope covariance | 0.13 | 0.46 | .78 |

Note. This (linear) model fits the data well: χ2 (df = 8) = 8.66, p = .417; root mean square error of approximation = .008.

A similar two-factor (slope and intercept) LGC model was estimated for the two social support measures (from friends and from family). The LGC models used the factor score comprised of the four individual social support items (quantity, frequency, ease, satisfaction) rather than modeling changes in each individual indicator as was done in the RM-ANOVA of Table 1. The LGC results are not shown in a separate table but are available by request. In general, these models had relatively low statistical fit (e.g., χ2 (df = 8) = 32.736; RMSEA = .102 for social support from friends), but the findings confirmed the results of the earlier RM-ANOVA analyses. First, when social support was measured as a latent construct, there was limited evidence for change over time. Social support from families appeared to marginally decline over time (σ 2= −.131, p < .001), whereas social support from friends remained fairly stable (p > .05). Second, like the results for loneliness, there were significant differences in the amount of social support reported (evidence for between-subject variation in intercepts) but very little variation in how social support changed over time (no evidence for variation in within-subject change). Third, also like the loneliness results, the nonsignificant covariance between intercept and slope (e.g., σ 2 = −.006, p = .950 for family social support) showed that change in social support over time was not related to the amount of support that a person experienced initially at time 01.

Next, we developed a model to explore whether social support modified the loneliness trajectories of widowed persons. Given our earlier finding that the social support indicators exhibited significant variation in intercept, but not slope, we estimated an LGC model of loneliness in which social support factors measured at time 01, rather than all four time points, predicted both the slope and the intercept of the loneliness trajectories (see Figure 1B). This chosen modeling strategy maintains the sizeable between-subject variation in social support intercepts but ignores the insignificant within-subject variation associated with social support over time. Results are presented in Table 3. Neither social support from friends nor social support from family was statistically associated with the slope of loneliness over time; this finding is not surprising because according to the unconditional model presented in Table 2, there was very little variation in the loneliness slopes to predict. On the other hand, this model found statistically significant associations between the social support and the intercept of loneliness: r friends = −.54, p < .001 and r family = −.20, p < .001. Those people who reported more social support also reported lower levels of loneliness. Also as shown in Table 3, the magnitude of the coefficient for friends was greater than that for family.

Table 3.

Change in Loneliness Scores Over Time, as Modified by Social Support

| Unstandardized (standardized) estimates | Standard error | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness intercept × friends | −3.35 (−.54) | 0.34 | <.001 |

| Loneliness intercept × family | −0.23 (−.20) | 0.06 | <.001 |

| Loneliness slope × friends | 0.11 (.16) | 0.08 | .21 |

| Loneliness slope × family | 0.01 (.11) | 0.40 | .40 |

Notes. Latent growth curve (LGC) was used to identify how social support from friends and family modified the loneliness trajectory (slope and intercept). Refer back to Model B of Figure 1. This model assumed linear change and fit the data well, χ2 (df = 14) = 15.385, p = .352; root mean square error of approximation = .018.

Table 4 presents results from an exploratory analysis identifying the covariates (n = 20) that might modify the loneliness experiences of widowed persons. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis and to minimize Type I errors, we applied a Bonferroni correction in which only p values less than .003 (.05/20) will be flagged for statistical significance. Not one of the 20 covariates predicted any variance in the slope of loneliness, but recall from Table 2 there was very little variance in the slopes of the loneliness trajectory to be explained, so this result was not unexpected. On the other hand, a few variables emerged as significant predictors of the loneliness intercept. For example, depression and loneliness were strongly positively correlated, with greater depression being associated with greater loneliness. As well, loneliness levels were lower among those who said they had a person with whom they could share their thoughts if they felt they had adequate opportunity to express themselves or if they formed a new friendship with a support group peer. Coefficients with p values between .05 and .003 are also presented in Table 3 and might well be considered in future studies of the influences on loneliness.

Table 4.

Standardized Coefficient Between Covariates and Loneliness Scores Over Time

| Covariates | Intercept | Slope |

|---|---|---|

| Age (0 = <70 or 1 = ≥70) | 0.37 (p = .01) | ns |

| Sex (1 = male, 2 = female) | ns | ns |

| Race (0 = white; 1 = other) | −0.12 (p = .05) | ns |

| Employed (0 = no; 1 = yes) | ns | ns |

| Education (at least college degree vs. less education) | ns | ns |

| Religion (Mormon or not) | ns | ns |

| Living arrangement (0 = alone; 1 = not alone) | ns | ns |

| Financial status (0 = not good to 2 = very good) | ns | ns |

| Happy marriage (1 = not happy to 7 = very happy) | −0.14 (p = .02) | ns |

| Death expected (1 = expected; 2 = unexpected) | ns | ns |

| General health (1 = poor to 7 = excellent) | −0.16 (p = .01) | ns |

| Depressive symptoms (0–15) | 0.55 (p < .001) | ns |

| Person to share thoughts with (0 = no, 1 = yes) | −0.23 (p < .001) | ns |

| Adequate opportunity to express self (0 = no, 1 = yes) | −0.51 (p < .001) | ns |

| Participation in social event (0 = none to 4 = often) | −0.16 (p = .01) | ns |

| Made new friend in group (0 = no; 1 = yes) | −0.24 (p < .001) | ns |

| Made a best friend in group (0 = no; 1 = yes) | −0.17 (p = .01) | ns |

| Study condition (support group A vs. B) | ns | ns |

| Attendance in support group (0–14 sessions) | ns | ns |

| Study site (San Francisco or Salt Lake City) | ns | ns |

Notes. ns = not significant at p < .05.

All models were estimated using a single covariate as potential modifier of both slope and intercept of loneliness. Refer back to Model B of Figure 1.

The final analysis used a series of hierarchical regressions to further explore which of these covariates uniquely explained variation in loneliness experiences. For this analysis, the factor score of loneliness at time 1 was regressed on each of the statistically significant covariates (i.e., the two latent constructs measuring social support from family and friends, plus the four additional covariates identified in Table 3). The top panel of Table 5 presents the adjusted R 2 values for bivariate regression equations, showing how much of the variance in loneliness scores was explained by each individual factor. Social support from friends accounted for 30% of the variance in loneliness scores. Having adequate opportunities to express self and depression accounted for 27% and 26% of variance in between-subject loneliness scores, whereas social support from family explained 19% of the differences in loneliness while making a new friend and having a person with whom you can share thoughts explained less than 5% of the variance. The bottom half of Table 5 presents estimates of explained variance for combinations of variables, which were entered into the equation in blocks. For example, social support from friends and family each uniquely explain some of the differences in loneliness scores. When social support from family was entered, it explained an additional 6% of variance over and above the 30% explained by social support from friends alone. Together, the two social support factor scores explained 36% of the variance in loneliness scores. The full model containing all six of the covariates explained more than half (54%) of the variance in loneliness scores. The amount of unique variance explained by each construct depended on the order in which the variables were entered into the models.

Table 5.

Explained Variance in Loneliness Scores

| Factors | Adjusted R 2 |

|---|---|

| Singlea | |

| Social support from friends | .30 |

| Social support from family | .19 |

| Adequate opportunity to express self | .27 |

| Depressive symptoms | .26 |

| Made a new friend | .05 |

| Person to share thoughts | .03 |

| Combinedb | |

| Social support from friend | .30 |

| + Social support from family | .36* |

| + Adequate opportunity to express | .43* |

| + Depressive symptoms | .53* |

| + Person to share and new friend | .54 |

Notes. Adjusted R 2 predicted from:

aSeparate bivariate regression equations of loneliness regressed on each factor.

bStepwise multiple regression equations where each factor was added to the previous model to explore the amount of unique variance explained by each factor.

*Denotes significant R 2 change from previous block, p < .05.

Discussion

Widowhood is regarded as one of the most distressing experiences in adulthood (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). Although increases in grief and depressive symptoms are the most commonly researched outcomes following the loss of a spouse or partner (Stroebe, Hansson, & Schut, 2008), 7 of 10 (70%) widowed persons report that loneliness is the biggest challenge to cope with on a day-to-day basis (Lund, 1989). Very few empirical studies have modeled loneliness as a dynamic, longitudinal outcome (Stroebe et al., 1996). As well, there has been a call in the literature for more studies differentiating the overlapping dimensions of loneliness and social support (Russell, Cutrona, McRae, & Gomez, 2012). Such analyses with a bereaved sample are especially interesting because widowhood marks the undeniable end of the intimacy, attachment, and support provided by the spouse (Ben-Zur, 2012; Pinquart, 2003) but is also typically associated with an outpouring of support from friends and family (Utz et al., 2002). The goals of this study were to distinguish between feeling lonely and being alone, how these constructs change over time, and whether social support from friends versus family has the potential to modify one’s experience of loneliness over time. We accomplished this using the LAL sample of adults aged 50+, who have experienced the loss of a spouse and who were longitudinally followed from approximately two to eighteen months postloss.

In general, loneliness decreased over time. Although there was significant variation in how much loneliness individuals reported, the overtime trend showed very little variation. In other words, reported feelings of loneliness decreased for most individuals in a very similar manner, regardless of how much loneliness they initially reported. The trend in decreasing loneliness was linear, suggesting that this decline may continue beyond what we measured here (2–18 months postloss). This suggests a somewhat universal pattern of adjustment, in which widowed persons eventually felt less lonely over time. Perhaps they got used to living alone and doing things as an individual, rather than as a couple. Perhaps they successfully readjusted their expectations about social support, social networks, and social relationships. These interpretations are consistent with the socio-emotional selectivity perspective (Adams et al., 2004; Carstensen, 1991), which suggests that the observed decrease in loneliness over time may indicate the bereaved person’ ability to renegotiate and redefine social relationships that are deemed most important and meaningful in the new context of widowhood, leading to lower feelings of loneliness over time. This theoretical explanation could also be used to suggest why there is so little variation in the loneliness trajectories over time and why the decline in loneliness was irrespective of how lonely someone felt overall.

In terms of longitudinal trajectories of social support, we found some evidence for changes in social support during the first year and a half of widowhood: For example, the reported size of support networks—both friends and family—declined over time. The frequency of contact with family, but not friends, also declined. Previous research comparing pre- and postbereavement levels of support finds a typical increase in social support from friends and family during the early months of bereavement (Scott et al., 2007; Utz et al., 2002); these results suggest that such support, especially that from family members, may trail off as bereaved persons adjust to being a widow(er). However, it should be noted that, according to the current analyses, there was no change in the more subjective evaluations of social support, such as the perceived ease of contact or satisfaction with family or friendship support. This suggests that the increased support received during the initial months of bereavement may be somewhat superficial or at least not central to the bereaved person’s actual need or desire for social support. Like the longitudinal analyses of loneliness, the two social support constructs had a lot interperson (intercept) variation but much less intraperson (slope) variation over time. This provides additional evidence for a fairly typical or universal trajectory of bereavement, in which the assumed increase in social support that immediately follows spousal loss (Scott et al., 2007; Utz et al., 2002) levels off as the reality of widowhood settles in.

As expected, individuals who reported the greatest levels of social support had the lowest reported levels of loneliness. Social support from both friends and family each explained a significant amount of variation in loneliness scores. Combined, these two sources of social support explained a little more than one-third of the total variance in loneliness scores (R 2 = .36). From a statistical standpoint, this suggests that there is quite a bit of empirical overlap between social support and loneliness, but the constructs remain distinct, as suggested by conceptual definitions distinguishing between “feeling alone” and “being alone” (Moustakas, 1961; Weiss, 1973). In more substantive terms, this means that social support plays an important and unique role in determining one’s feelings of loneliness after widowhood, but that the feelings of loneliness are not determined solely by the quantity or quality of one’s social support networks. Therefore, increasing one’s social support following widowhood will not necessarily minimize or eliminate one’s feelings of loneliness following the loss of a spouse.

Additional covariates were found to explain some of the variation in the loneliness experiences of newly bereaved persons. These included having adequate opportunities to express one’s self, having a confidant to share thoughts with and making a new friend who is also widowed. This set of significant covariates provides specific examples of potential mechanisms through which social support may affect feelings of loneliness. For example, widowed persons seem to desire or require opportunities to express one’s feelings, particularly with someone who has shared the experience of widowhood. Although past research has suggested that old friends typically provide the most effective support (Potts, 1997), these findings suggest that in the face of widowhood a “new” friend, especially one who has also recently experienced spousal loss, may provide a unique and important source of support and camaraderie for widowed persons. Bereavement support groups or widow-to-widow peer programs may be a way to provide opportunities for bereaved persons to express their feelings and a way to provide the added benefit of peer reassurance, thereby reducing one’s overall challenges with loneliness following widowhood. Finally, the very loneliest people in this study were the 11 people who said they had someone to share their thoughts with, but that the person was not readily available. Thus, social support, no matter how or by whom it is provided, needs to be readily and easily accessible if it is to be an effective buffer against loneliness in a widowed population.

Previous research has found that friends, more than family members, play a defining role in the well-being of older adults (Giles, Glonek, Luszcz, & Andrews, 2005) and among widowed persons specifically (see deVries, Utz, Caserta, Lund, in press). This ability of analysis to measure social support from friends versus family separately confirms those findings, revealing that although both family and friends play a unique and important role in buffering the feelings of loneliness after spousal loss, friendships appear to protect against loneliness more than family members do. This is likely attributable to the fact that friendships are typically formed on the basis of mutual choice and interest, whereas family relationships are typically defined by marriage or by blood (Lee & Ishii-Kuntz, 1987). As a result, friends tend to offer a commonality of experiences and voluntary diversionary activities, whereas interactions with family members, especially during the earliest months of bereavement, may be focused more on obligatory responsibilities such as estate planning and paying medical bills (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006). The different functions served by friends versus family members likely explain why social support from friends seems to be more important to newly bereaved persons’ well-being than support received from family members. Although it should be noted that family members can and often do serve in personally rewarding and mutually beneficial support roles, just as friends do. This is evidenced by the strong and unique associations among social support from friends and from family with loneliness. Both types of social support appear to be important protective factors against loneliness; friends provide a slightly greater protective advantage.

The sample used for these analyses afforded a longitudinal view of loneliness, which is a noted strength of this study (Stroebe et al., 1996), However, these analyses used only time-invariant predictor variables to model the trajectories of loneliness over time. Future research may want to expand these models to include time-varying covariates. For example, these analyses found a positive correlation between depressive symptoms and loneliness. This finding provides empirical evidence supporting statements made by Cohen (2000) in an editorial suggesting that loneliness may be a “near depression” and that there is conceptual overlap between these constructs. Future studies could further explore the causal direction of this association: does depression cause loneliness, or does loneliness perhaps affect mental and physical health? Similarly, future studies might also want to further explore the causal ordering between social support and loneliness. For purposes of this analysis, we assumed that social support is a predictor of loneliness, but it could be argued that people with high levels of loneliness may elicit increased social support from friends or family members. Future work that incorporates time-varying covariates could further explore the temporal ordering of these associations to better understand the dynamics of loneliness over time and how loneliness may be a response to concomitant shifts in mental health or social support.

Although the LAL study afforded a much needed longitudinal analysis of loneliness, its sample represents a subset of widowed persons who agreed to participate in the intervention and research protocols of this study. The limitations of this sample should be noted; and caution should be taken when generalizing the results to all widowed persons. Furthermore, the LAL study did not contain a nonbereaved control group or measures of loneliness prior to the death. Thus, it is difficult to know whether loneliness spiked immediately following the loss (prior to the baseline assessment at approximately three months postloss) and whether the observed decline in the first year and a half of bereavement represents a return toward some baseline or predeath level. Without predeath measures of loneliness or a comparable nonbereaved sample (i.e., married, aged 50+), it is impossible to know the causal nature between widowhood and loneliness. This study provides evidence of a typical pattern of decreasing loneliness during the first year and a half of bereavement, but it does not show how loneliness changes before and immediately after the experience of spousal loss. Future studies should gather predeath measures of loneliness so that the trajectory of loneliness following widowhood can be further illuminated. It is possible, for example, that spouses responsible for significant caregiving may withdraw emotionally and socially from social networks prior to the death (Cooke, McNally, Mulligan, Harrison, & Newman, 2001; Loos & Bowd, 1997), perhaps leading to a heightened sense of loneliness prior to death for this subgroup of widow(er)s. Another possibility is that the feelings of loneliness may be most intense during the early days or weeks of bereavement when the surviving spouse first experiences his or her home and daily life without a spouse present.

Conclusion

Overall, this study explored the dynamic relationship between loneliness and social support within a recently bereaved sample of older spouses. Although there is considerable empirical overlap between social support and loneliness, the expression of loneliness (feeling lonely) appears to be distinct from the reality of one’s social support (being alone). The social support received from friends appears to be slightly more meaningful than the support from family members. This is stated not to downplay the important role that family members play in supporting recently bereaved persons but to emphasize the critical role that friends might play in supporting recently bereaved persons. Finally, this study provides compelling evidence that although there is great variation in the feelings expressed and the perceived quality of social support reported, most bereaved spouses undergo similar processes of change over time. In this regard, it seems that widowhood requires an inevitable period of readjustment, in both how much loneliness is felt and how much social support is received.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of Aging at the National Institute of Health (NIA-R01-AG023090).

Acknowledgments

R. L. Utz conceptualized the analyses, did the statistical work, wrote and revised the manuscript, and was an investigator and Project Director on the Living After Loss project. K. L. Swenson assisted with the analyses. M. Caserta, D. Lund, and B. De Vries edited the current manuscript and were responsible for the original design and data collection for the Living After Loss project.

References

- Adams K. B., Sanders S., Auth E. A. (2004). Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: Risk and resilience factors. Aging & Mental Health, 8, 475–485. 10.1080/13607860410001725054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J. C. (2002). Neighbors, friends, and other nonkin caregivers of community-living dependent elders. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57, S158–S167. 10.1093/geronb/57.3.S158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal C. (2006). Loneliness in older women: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27, 795–813. 10.1080/ 01612840600781196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zur H. (2012). Loneliness, optimism, and well-being among married, divorced, and widowed individuals. The Journal of Psychology, 146, 23–36. 10.1080/00223980.2010.548414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkel I., Wijk H., Molander U. (2009). Family and friends provide most social support for the bereaved. Palliative Medicine, 23, 141–149. 10.1177/0269216308098798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G. (2002). Self-efficacy and depression in late life: A primary prevention proposal. Aging & Mental Health, 6, 315–324. 10.1080/1360786021000006938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Elizabeth M., Waite L. J., Hawkley L. C., Thisted R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and aging, 21, 140–151. 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., Nesse, Wortman C. (Eds.). (2006). Spousal bereavement in late life. New York: Springer Publishing Company [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. (1991). Selectivity theory: Social activity in life-span context. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 11, 195 [Google Scholar]

- Caserta M., Utz R., Lund D., de Vries B. (2010). Sampling, recruitment, and retention in a bereavement intervention study: Experiences from the Living After Loss Project. Omega, 61, 181–203. 10.2190/OM.61.3.b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G. D. (2000). Aging at a turning point in the 21st century. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 8, 1–3. 10.1097/00019442-200002000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke D. D., McNally L., Mulligan K. T., Harrison M. J., Newman S. P. (2001). Psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 5, 120–135.10.1080/13607860120038302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deVries B., Utz R. L., Caserta M., Lund D. (in press). Friend and family contact and support in early widowhood. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbt078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Donnelly E. A., Hinterlong J. E. (2010). Changes in social participation and volunteer activity among recently widowed older adults. The Gerontologist, 50, 158–169. 10.1093/geront/gnp103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fees B. S., Martin P., Poon L. W. (1999). A model of loneliness in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54, P231–P239. 10.1093/geronb/54B.4.P231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles L. C., Glonek G. F., Luszcz M. A., Andrews G. R. (2005). Effect of social networks on 10 year survival in very old Australians: The Australian longitudinal study of aging. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 574–579. 10.11 36/jech.2004.025429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich L. M., Gullone E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 695–718. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes T. H., Rahe R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218. 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmén K., Furukawa H. (2002). Loneliness, health and social network among elderly people: A follow-up study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 35, 261–274. 10.1016/S0167-4943(02)00049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. R., Ishii-Kuntz M. (1987). Social interaction, loneliness, and emotional well-being among the elderly. Research on Aging, 9, 459–482. 10.1177/0164027587094001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy L. H., Derby J. F. (1992). Bereavement support groups: Who joins; who does not; and why. American Journal of Community Psychology, 20, 649–662. 10.1007/BF00941507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos C., Bowd A. (1997). Caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: Some neglected implications of the experience of personal loss and grief. Death Studies, 21, 501–514. 10.1080/074811897201840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopata H. Z. (1996). Current widowhood: Myths and realities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications [Google Scholar]

- Lund D. A. (1989). Conclusions about bereavement in later life and implications for interventions and future research. In Lund D. A. (Ed.), Older bereaved spouses: Research with practical applications. Amityville, NY: Taylor and Francis/Hemisphere [Google Scholar]

- Lund D., Caserta M., Utz R., Devries B. (2010a). A tale of two counties: Bereavement in socio-demographically diverse places. Illness, Crises, and Loss, 18, 301–321. 10.2190/IL.18.4.b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund D., Caserta M., Utz R., de Vries B. (2010b). Experiences and early coping of bereaved spouses/partners in an intervention based on the dual process model (dpm). Omega, 61, 291–313. 10.2190/OM.61.4.c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A. M., Kim Y., Prigerson H. G., Mortimer-Stephens M. (2004). Complicated grief in survivors of suicide. Crisis, 25, 12–18. 10.1027/02227-5910.25.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas C. E. (1961). Loneliness. New York: Prentice-Hall [Google Scholar]

- Perlman D., Peplau L. A. (1982). Theoretical approaches to loneliness. In Peplau L. A., Perlman D. (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook for current theory, research, and therapy (pp. 123–134). New York: Wiley Interscience [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M. (2003). Loneliness in married, widowed, divorced, and never-married older adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20, 31–53. 10.1177/0265407503020001186 [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sörensen S. (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23, 245–266. 10.1207/153248301753225702 [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sörensen S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, P33–P45. 10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts M. K. (1997). Social support and depression among older adults living alone: The importance of friends within and outside of a retirement community. Social Work, 42, 348–362. 10.1093/sw/42.4.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokach A. (2011). From loneliness to belonging: A review. Psychology Journal, 8, 70–81 [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. W., Cutrona C. E., McRae C., Gomez M. (2012). Is loneliness the same as being alone? The Journal of psychology, 146, 7–22. 10.1080/00223980.2011.589414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savikko N., Routasalo P., Tilvis R., Pitkälä K. (2010). Psychosocial group rehabilitation for lonely older people: Favourable processes and mediating factors of the intervention leading to alleviated loneliness. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 5, 16–24. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. B., Bergeman C. S., Verney A., Longenbaker S., Markey M. A., Bisconti T. L. (2007). Social support in widowhood: A mixed methods study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1, 242–266. 10.1177/1558689807302453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro A. (2004). Revisiting the generation gap: Exploring the relationships of parent/adult-child dyads. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 58, 127–146. 10.2190/EVFK-7F2X-KQNV-DH58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. Omega, 61, 273–289. 10.2190/OM.61.4.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M. S., Hansson R. O., Schut H. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of bereavement research and practice: Advances in theory and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W., Stroebe M., Abakoumkin G., Schut H. (1996). The role of loneliness and social support in adjustment to loss: A test of attachment versus stress theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1241–1249. 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz R. L., Carr D., Nesse R., Wortman C. B. (2002). The effect of widowhood on older adults’ social participation: An evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. The Gerontologist, 42, 522–533. 10.1093/geront/42.4.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz R. L., Caserta M., Lund D. (2012). Grief, depressive symptoms, and physical health among recently bereaved spouses. The Gerontologist, 52, 460–471. 10.1093/geront/gnr110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. S. (1973). Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]