Abstract

Described here is the synthesis and characterization of a novel, bioreducible linear poly(β-amino ester) designed to condense siRNA into nanoparticles and efficiently release it upon entering the cytoplasm. Delivery of siRNA using this polymer achieved near-complete knockdown of a fluorescent marker gene in primary human glioblastoma cells with no cytotoxicity.

RNA interference (RNAi)-induced gene knockdown is an exciting, naturally occurring cellular pathway that targets mRNA transcripts for cleavage in a sequence-specific manner.1 This pathway can be exploited to target specific genes and alter cellular behaviour with the delivery of short interfering RNA (siRNA) complementary to the mRNA transcript of the gene of interest.2 However, the therapeutic potential of siRNA cannot be realized without efficient delivery to its site of action in the cytoplasm. A promising approach lies in polymeric delivery vehicles such as poly(β-amino ester)s (PBAEs), which spontaneously form nanoparticles with nucleic acids when in an aqueous environment.3 This electrostatically driven interaction for self-assembly allows flexibility in terms of nucleic acid sequences and therefore has a wide range of potential disease targets.

PBAE-nucleic acid nanoparticles allow nucleic acid release by hydrolytic degradation of esters along the polymer backbone on the time scale of several hours to a few days.4 However, this release mechanism limits control over where release will occur. In order to specifically target release to the cytoplasm, we have synthesized a novel linear PBAE polymer with disulfide bonds along the polymer backbone.

Disulfide bonds can be degraded reductively in the human body via glutathione (GSH), which is present predominantly in the cytosol of human tissues at concentrations ranging from 1-8 mM, three orders of magnitude greater than the concentration in blood serum (5-50 μM).5 This property can be harnessed to target siRNA release to its site of action in the cytoplasm by employing disulfide-containing polymers as vectors.

Bioreducible polymers have been examined for both DNA and siRNA delivery (for review see Son et. al.6). Manickam et. al. created reducible copolypeptides containing histidine-rich and nuclear localization sequences for DNA delivery and were able to show comparable transfection efficiency versus 25 kDa branched polyethyleneimine (bPEI) with significantly lower toxicity. Peng et. al. showed that bPEI containing disulfide bonds (PEI-SS) reduced cytotoxicity and promoted intracellular release of plasmid DNA versus 25 kDa bPEI, which led to higher transfection efficacy.7 Breunig et. al. later successfully employed PEI-SS for siRNA delivery in Chinese hamster ovary cells using a linear PEI-SS. Linear PEI-SS showed marked increases in gene knockdown versus its nonreducible analog and was able to match the knockdown achieved by bPEI.8 Another step forward in the optimization of polymeric siRNA delivery was later shown by van der Aa et. al. using poly(amido amine)s with tunable charge densities in a human lung carcinoma cell line, in which they were able to achieve knockdown comparable to Lipofectamine™ 2000.9

In this manuscript, we sought to create a new bioreducible nanobiotechnology that could be highly effective for siRNA delivery to human cells. As the literature shows that lipid-based transfection reagents, such as the leading commercially available reagent Lipofectamine™ 2000, are generally superior for siRNA delivery compared to polymers such as PEI, we used Lipofectamine™ 2000 as the benchmark positive control. Recently, other disulfide-containing PBAE nucleic acid delivery vehicles for RNAi have been investigated. Yin et. al. formed disulfide-containing PBAEs for plasmid delivery of short hairpin RNA (shRNA), but as diamines and diacrylates were used for polymerization, degree of branching was not user-controlled, which could compromise the reproducibility of the material properties.10 Additionally, while this method was effective for delivery of plasmid DNA, reports have shown standard linear PBAEs are generally ineffective for siRNA delivery without the use of additional components.11 This is not unexpected as siRNA is a molecule ∼200-times smaller than DNA and its delivery may require different biomaterials. Our group recently described linear PBAEs containing disulfide bonds only in the polymer end-cap groups, not in the main base polymer, and used them for siRNA delivery to promote siRNA triggered released into the cytosol.12 These polymers were effective and presented an interesting initial step for creating PBAE-based siRNA delivery polymers, and motivated the work presented herein.

We hypothesized that a new reducible, disulfide-containing analog of a previously established non-reducible PBAE polymer would promote enhanced siRNA-mediated gene knockdown. Our goal was to create reducible nanoparticles that would be as physically identical as possible to their non-reducible analogs when in an extracellular environment, but would then efficiently release siRNA when in a reducing cytoplasmic environment.

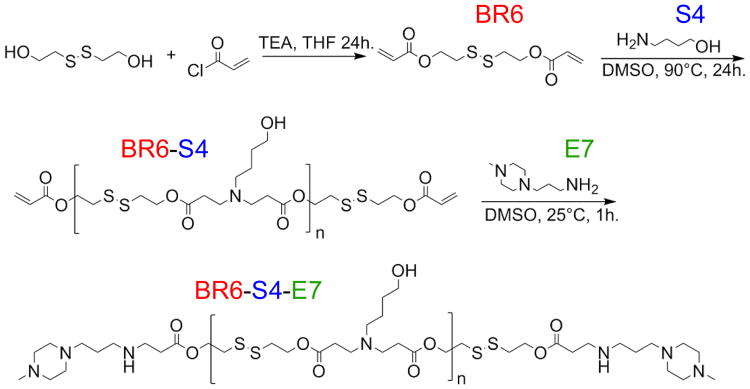

We synthesized a new reducible form of a monomer that we have previously used, hexane-1,6-diyl diacrylate (B6) to form “reducible B6,” 2,2′-disulfanediylbis(ethane-2,1-diyl) diacrylate (BR6), in order to form polymers with similar structure and the same charge density as B6 polymers. Synthesis of BR6 was carried out in a method similar to Chen et. al.13 Briefly, bis(2-hydroxyethyl) disulfide was acrylated with acryloyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine (TEA). Following reaction, TEA HCl precipitate was removed by filtration, and the product was purified with aqueous Na2CO3 washes followed by rotary evaporation (Scheme 1). The product was confirmed by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (H1-NMR).†

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of R647.

The two-step polymer synthesis was carried out in a similar manner as in Bhise et. al.14 Either diacrylate monomer, BR6 or B6, was polymerized with 4-amino-1-butanol (S4) in a 1.01:1 molar ratio, yielding acrylate terminated base polymers. The B6-S4 or BR6-S4 base polymers were then end-capped with 1-(3-aminopropyl)-4-methylpiperazine (E7) to yield either B6-S4-E7 (647) or BR6-S4-E7 (R647). End-cap E7 was chosen as it has been shown to work well for PBAE delivery of siRNA in our preliminary studies with non-reducible polymers.15 Polymer size and structure were confirmed using gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and H1-NMR, respectively.† GPC results of R647 yielded MN of 3745 Da, MW of 7368 Da, and a PDI of 1.967. GPC results of 647 yielded a comparable size profile (MN 4037 Da, MW 6221 Da, PDI 1.597).

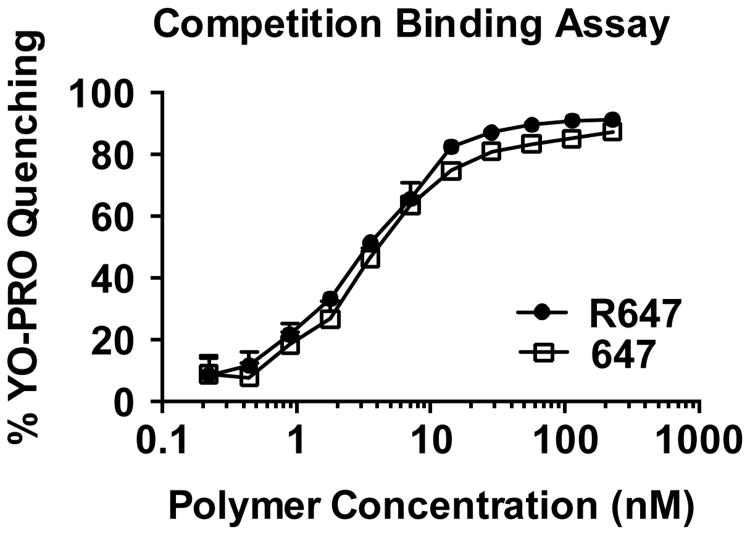

The siRNA binding capability of each polymer was evaluated by a YO-PRO®-1 Iodide competition binding assay (Figure 1), in which YO-PRO®-1 Iodide fluoresces upon binding siRNA and is quenched as it is displaced by increasing concentrations of polymer. Over the polymer concentrations tested, R647 showed comparable to slightly higher siRNA binding affinity compared to 647 as measured by YO-PRO®-1 Iodide quenching.

Figure 1.

Polymer/siRNA competitive binding assay for R647 and 647. Polymer to siRNA binding strength is assessed by quenching of YO-PRO®-1 Iodide fluorescence over increasing polymer concentrations.

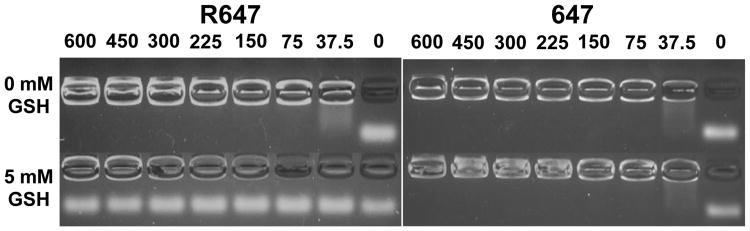

Polymer-siRNA binding was further characterized using a gel retention assay (Figure 2), in which nanoparticles are added to the wells of an agarose gel, and tightly bound siRNA is unable to migrate under electric field (100 V). In order to repeat this assay in conditions mimicking the reducing cytoplasmic environment, GSH was added to the particles (final concentration 5 mM) immediately prior to electrophoresis. Without GSH, both R647 and 647 showed complete siRNA complexation with polymer:siRNA weight ratios (wt/wts) as low as 75:1. In the presence of cytoplasmic levels of GSH, R647 completely released siRNA, even at the highest wt/wt examined, while 647 binding was unaffected. GPC results of each polymer show that incubation with 5 mM GSH for 5 min is capable of degrading R647 but not 647 (Figure S1). These results combined with the competition binding data show that R647 can not only condense and protect siRNA as well as or slightly better than 647 when in extracellular conditions but is also able to completely release siRNA within minutes of exposure to cytoplasmic GSH levels.

Figure 2.

Gel retention assay. Gel electrophoresis image of siRNA complexed with R647 (left) or 647 (right) in the absence (0 mM) or presence (5 mM) of GSH. Numbers above each well indicate the polymer to siRNA weight ratio.

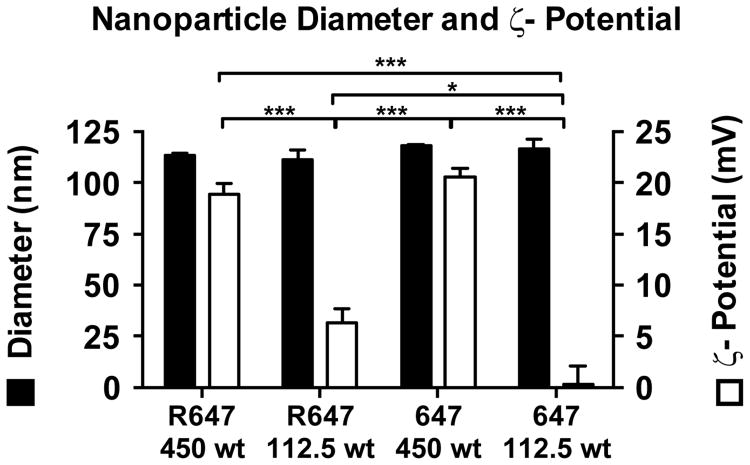

Nanoparticles formed from R647 and 647 were characterized by size via nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using a NanoSight NS500 and surface charge (ζ-potential) via dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Malvern Zetasizer NanoZS (Figure 3). For each polymer, nanoparticles were formed at either 450 wt/wt or 112.5 wt/wt. For all four formulations tested, nanoparticle diameter remained between 111 nm and 118 nm, which falls in the appropriate size range for efficient cellular uptake.3 For particles formed at 112.5 wt/wt with either R647 or 647, ζ-potential was neutral (between -10 and +10 mV), while particles formed at 450 wt/wt with R647 or 647 had a ζ-potential of 19.0 ± 1 mV and 20.6 ± 1 mV, respectively.

Figure 3.

Nanoparticle size and surface charge. Nanoparticle diameter and ζ-potential of particles formed using either R647 or 647 at either 450 wt/wt or 112.5 wt/wt. Nanoparticle diameter was measured using NTA. ζ-potential was measured using DLS. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's Multiple Comparison post-tests. Nanoparticle diameters of all samples were not significantly different (p > 0.05). Nanoparticle zeta potentials that are statistically significant are indicated (* = p<0.05, *** = p<0.001).

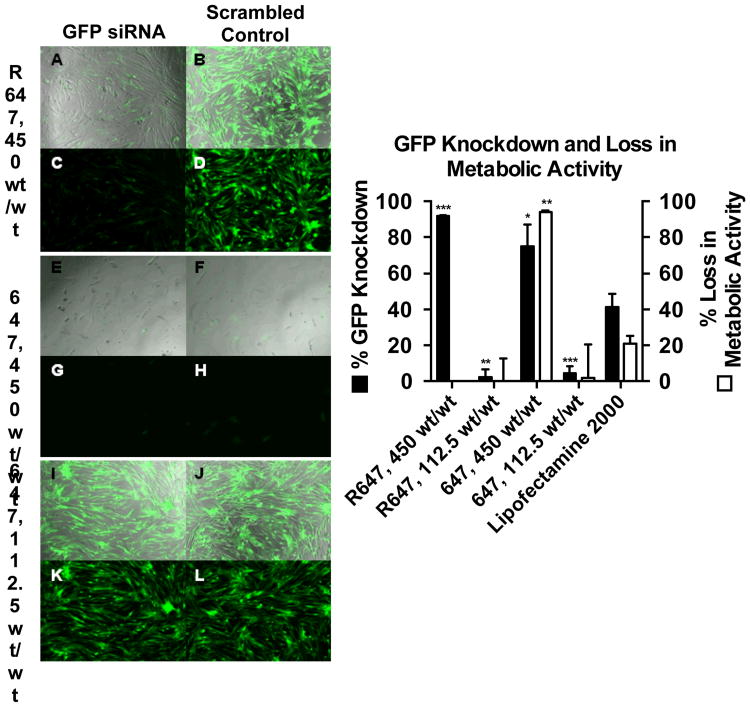

Gene knockdown and cellular loss in metabolic activity were evaluated in glioblastoma GBM 319 cells expressing constitutive GFP,16 using siRNA targeted at GFP with sequence 5′-CAAGCUGACCCUGAAGUUCTT (sense) and 3′-GAACUUCAGGGUCAGCUUGCC (antisense), or a scrambled control siRNA (scRNA) with sequence 5′-AGUACUGCUUACGAUACGGTT (sense) and 3′-CCGUAUCGUAAGCAGUACUTT (anti-sense) (Figure 4). Loss in metabolic activity was measured 24 h post transfection using a CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution cell proliferation assay and read using a BioTek® Synergy™ 2 Microplate Reader. GFP expression was measured 9 d post-transfection using a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (emission filter: 530/30 nm). Transfections were performed with 26.7 nM siRNA using R647 or 647 at either 450 wt/wt or 112.5 wt/wt. The 450 wt/wt formulation of 647 achieved 75 ± 12% GFP knockdown but with 94 ± 1% loss in metabolic activity, indicating that this treatment was very toxic. The 112.5 wt/wt formulations of R647 and 647 did not exhibit toxicity, but were unable to achieve substantial GFP knockdown (2 ± 4% and 4 ± 4% knockdown, respectively). There is no concentration at which 647 is both safe and effective.17 Incredibly, R647 at 450 wt/wt achieved 92 ± 1% GFP knockdown, with no measurable loss in metabolic activity. This demonstrates that addition of a bioreducible moiety to the PBAE backbone not only improved siRNA delivery but also attenuated toxicity. Compared to the leading commercially available reagent Lipofectamine™ 2000, R647 achieved more than double the % knockdown and prevented typically observed cytotoxicity.

Figure 4.

Day 9 gene knockdown of GFP+ GBM 319 cells transfected with R647 and 647 at either 450 or 112.5 wt/wt with 26.7 nM siRNA targeted against GFP. Left panel: Brightfield images of R647, 450 wt/wt treated cells (A,B) and 647, 112.5 wt/wt treated cells (I,J) show viable cells while 647, 450 wt/wt treated cells (E,F) show significant toxicity. Fluorescence images of R647, 450 wt/wt treated cells show significantly less GFP expression when formulations contain GFP siRNA (C) versus scrambled control siRNA (D). Fluorescence images of 647, 112.5 wt/wt treated cells show comparable GFP expression in both GFP siRNA (K) and scrambled control treated cells (L). Right panel: Graphical representation of knockdown and loss in metabolic activity results. Lipofectamine™ 2000 positive control with 26.7 nM siRNA is used as the control for statistical comparisons by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-tests (* = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001).

We have synthesized and characterized a novel bioreducible PBAE for siRNA delivery that is both efficacious and non-cytotoxic. The reducible polymer R647 was shown to bind siRNA as well as or slightly better than its non-reducible analog 647. It was determined that this new polymer is capable of condensing siRNA in nanoparticles with the same physical properties as the previously established 647 particles. It was also shown that siRNA release from R647 occurs within minutes of entering a reducing environment comparable to cytosol. We finally demonstrated that R647 nanoparticles that differed from 647 only in reducibility were able to achieve near-complete gene knockdown with no toxicity in human brain cancer cells, while analogous 647 nanoparticles were either extremely toxic or ineffective. This new class of polymer has exciting therapeutic potential as a safe and effective siRNA delivery vehicle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH (1R01EB016721 and R21CA152473). KLK thanks the NIH Cancer Nanotechnology Training Center (R25CA153952) at the JHU Institute for Nanobiotechnology for fellowship support and SYT thanks the National Science Foundation for fellowship support The authors thank the Microscopy and Imaging Core Module of the Wilmer Core Grant, EY001765 for flow cytometry studies.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures, synthesis methods, and NMR results are included in the supporting information. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuwabara PE, Coulson A. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:347–349. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green JJ, Langer R, Anderson DG. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:749–759. doi: 10.1021/ar7002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynn DM, Langer R. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10761–10768. [Google Scholar]; Sunshine JC, Peng DY, Green JJ. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:3375–3383. doi: 10.1021/mp3004176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith OW. Free Radical Biol Med. 1999;27:922–935. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Son S, Namgung R, Kim J, Singha K, Kim WJ. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1100–1112. doi: 10.1021/ar200248u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng Q, Zhong Z, Zhuo R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:499–506. doi: 10.1021/bc7003236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breunig M, Hozsa C, Lungwitz U, Watanabe K, Umeda I, Kato H, Goepferich A. J Controlled Release. 2008;130:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Aa L, Vader P, Storm G, Schiffelers R, Engbersen J. J Controlled Release. 2011;150:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin Q, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Zhang P, Li Y. J Controlled Release. 2011;151:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yin Q, Shen J, Chen L, Zhang Z, Gu W, Li Y. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6495–6506. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JS, Green JJ, Love KT, Sunshine J, Langer R, Anderson DG. Nano Lett. 2009;9:2402–2406. doi: 10.1021/nl9009793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzeng SY, Hung BP, Grayson WL, Green JJ. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8142–8151. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Qiu X, Ouyang J, Kong J, Zhong W, Xing MM. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3601–3611. doi: 10.1021/bm200804j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhise NS, Gray RS, Sunshine JC, Htet S, Ewald AJ, Green JJ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8088–8096. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzeng SY, Yang PH, Grayson WL, Green JJ. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:3309–3322. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S27269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzeng SY, Guerrero-Cazares H, Martinez EE, Sunshine JC, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Green JJ. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5402–5410. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzeng SY, Green JJ. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2013;2:468–480. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.