Abstract

Sedentary screen time (watching TV or using a computer) predicts cardiovascular outcomes independently from moderate and vigorous physical activity and could impact left ventricular structure and function through the adverse consequences of sedentary behavior.

Purpose

To determine whether sedentary screen time is associated with measures of left ventricular structure and function.

Methods

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study measured screen time by questionnaire and left ventricular structure and function by echocardiography in 2,854 black and white participants, aged 43–55 years, in 2010–2011. Generalized linear models evaluated cross-sectional trends for echocardiography measures across higher categories of screen time and adjusting for demographics, smoking, alcohol, and physical activity. Further models adjusted for potential intermediate factors (blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, diabetes, and body mass index (BMI).

Results

The relationship between screen time and left ventricular mass(LVM) differed in blacks vs. whites. Among whites, higher screen time was associated with larger LVM (P<0.001), after adjustment for height, demographics, and lifestyle variables. Associations between screen time and LVM persisted when adjusting for blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, and diabetes (P=0.008) but not with additional adjustment for BMI (P=0.503). Similar relationships were observed for screen time with LVM indexed to height2.7, relative wall thickness, and mass-to-volume ratio. Screen time was not associated with left ventricular structure among blacks or left ventricular function in either race group.

Conclusions

Sedentary screen time is associated with greater LVM in white adults and this relationship was largely explained by higher overall adiposity. The lack of association in blacks supports a potential qualitative difference in the cardiovascular consequences of sedentary screen-based behavior.

Keywords: Left Ventricular Mass, Sedentary Time, Race Differences, Echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

Sedentary time has emerged as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes and mortality, even among individuals who meet recommendations for physical activity.(19, 34) Thus, being ‘sedentary’ should no longer be considered the opposite of being ‘active’, but rather an additional metric by which to classify an individual’s overall activity pattern. Understanding how sedentary time contributes to cardiovascular disease is an important area in need of more research. Time spent sitting in screen-based activities for entertainment purposes (e.g. television viewing, using a computer or playing sedentary video games) is a particularly relevant target because it is a major contributor to overall sedentary time(2) and is potentially modifiable.

One pathway through which sedentary behavior may contribute to cardiovascular disease is through an impact on the myocardium. Left ventricular structure and function, most notably left ventricular mass (LVM), reflect adaptions to changes in workload and predict cardiovascular events and mortality.(14, 22, 27) LVM associates with various cardiovascular risk factors, including age, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, physical activity, alcohol intake, and smoking,(9, 10, 12) but the relationship between sedentary time and left ventricular structure and function has not been studied. While LVM and left ventricular volumes tend to decrease with bed rest or deconditioning,(28, 33) the chronic consequences of free-living sedentary time, i.e. increased obesity or obesity-related comorbidities,(16) are generally associated with increased LVM and worse cardiac function.(9, 10, 18) Exercise also increases LVM and volumes, though these changes are considered favorable adaptions to training.(5, 31, 36) Thus, it is unclear whether and in which direction sedentary time would be related to left ventricular structure and function independently of physical activity, obesity, and obesity-related comorbidities.

Furthermore, it may be possible that the relationship between sedentary time and left ventricular structure and function differs between white and black adults. Data from the National Health and Nutritional Exam (NHANES) suggests that sedentary time is associated with cardiovascular risk factors and obesity in whites but not blacks.(15) If sedentary time impacts left ventricular structure and function through a pathway of adverse effects on obesity and cardiovascular risk factors, a differential effect across races might be expected.

Elucidating the association of sedentary screen time with left ventricular structure and function is of interest in a population-based cohort to inform public health recommendations about screen-based sedentary behavior. The primary objective of the current study was to investigate associations of recreational, sedentary screen time with LVM and other measures of left ventricular structure and function, independent of moderate and vigorous leisure-time physical activity, in the community-based Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Secondary objectives were to determine whether associations were consistent between white and black adults, and across levels of physical activity.

METHODS

Sample Population

The CARDIA Study enrolled 5,115 black and white adults aged 18–30 years in 1985 and 1986 in Birmingham, AL, Chicago, IL, Minneapolis, MN, and Oakland, CA. CARDIA is a longitudinal cohort study of the development and determinants of cardiovascular disease over time.(8) Follow-up examinations of the cohort have been conducted approximately every 2–5 years with the most recent examination having occurred in 2010–2011 (year 25). A total of 3,499 participants (72% of the surviving CARDIA cohort) participated in the year 25 exam. Of these, 3,475 completed an echocardiogram; measures of left ventricular structure and function were available in 3,121. We further excluded 90 participants with adjudicated cardiovascular or related endpoints (myocardial infarction, angina, revascularization procedure, peripheral artery disease, stroke, chronic heart failure, or end-stage renal disease), 83 participants with poor quality images, and 91 participants with missing covariate information. This resulted in a final sample size of 2,854. Participants excluded were slightly older, more likely to be men or black, complete less education, and had higher median sedentary screen time (3.3 hours/day in excluded vs. 2.9 hours/day in included, P<0.001). Each CARDIA site obtained approval for all study procedures from a local institutional review board and informed consent from each participant prior to study assessments.

Measurements

Standardized protocols for data collection were used across study centers. Participants were asked to fast for at least 12 hours before each examination and to avoid smoking or engaging in vigorous physical activity for at least 2 hours.

Sedentary Time

Sedentary time was measured for the first time among CARDIA participants at the year 25 exam using a questionnaire adapted from sedentary behavior questionnaires used in children and adolescents.(26, 29) The questionnaire measured non-work related sedentary time with six questions including television viewing, computer use, travelling in a vehicle, doing paperwork, talking on the phone, or other sedentary recreational activities (e.g. reading a book). Participants could choose one of nine potential durations foreach of these activities with a minimum of ‘none’ and a maximum of ‘6 or more hours’. Participants reported usual weekday and weekend behavior separately. For the current analysis, sedentary screen time was calculated as a weighted average of reported weekday and weekend time spent watching television or using a computer for non-work related activities. Total sedentary time was also calculated as the weighted average over all six non-work sitting activities assessed. Two studies using comparable questionnaires reported good reliability and fair to good validity, commensurate with other activity questionnaires.(24, 30)

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed at all four CARDIA field centers at the year 25 exam using an Artida 2D (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) and a previously described protocol.(10) Briefly, M-mode echocardiography was used to measure left ventricular dimensions based on the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines.(20) LVM was calculated using the Devereux formula.(7) Because various allometric scaling exponents have been used to index LVM to height, we used methods described by Chirinos and colleagues (3) to estimate non-linear relationships between LVM and height within our study population. The exponent was 0.99 (95% confidence interval 0.75, 1.23) when including gender in the estimation model. This suggests that height should be taken to approximately the first power, which is equivalent to a linear relationship between height and LVM. Moreover, relationships with screen time were similar whether we used LVM adjusted for height as a covariate, LVM indexed to height2.7, or LVM indexed to height1.7. Thus, we report 1) LVM with linear adjustment for height as a covariate based on the mathematical relationship in our study population and 2) LVM indexed to height2.7(LVMi) for consistency with other CARDIA reports.(10) Left ventricular end diastolic volumes (EDV) and end systolic volumes (ESV) were acquired from a 2-dimensional 4-chamber view and were indexed to height. Mass-to-volume ratio was calculated as the ratio of LVM to EDV (g/mL). Relative wall thickness was calculated as the sum of the posterior wall and interventricular septal thicknesses divided by the internal left ventricular diameter, with all measures taken at diastole.(6) Stroke volume was the difference between ESV and EDV. Ejection fraction was the ratio of stroke volume to EDV. Sonographers at each field center underwent initial, centralized training followed by ongoing quality assurance and control procedures to assess intra- and inter-sonographer reproducibility. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) for repeated LVM, EDV, and ejection fraction ranged from 0.6–0.9. Scans were read at a centralized reading center. ICCs across readers and within readers ranged from 0.6–0.9.

Other Covariates

Physical activity was assessed using the CARDIA physical activity questionnaire. This modified version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire assesses duration and intensity of various non-occupational activities and uses formulas to calculate moderate and heavy (vigorous) intensity activity in exercise units (EU).(17) As a point of reference, 300 EU corresponds roughly to meeting the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Guidelines for Physical Activity (37) of 150 moderate or 75 vigorous minutes of weekly physical activity. Education (years), alcohol consumption (mg/day) and smoking (never, former, or current) were assessed by questionnaire. Height and weight were measured in light clothing with a stadiometer and balance beam scale and BMI was calculated as kg/m2. Diabetes was defined as either the use of diabetes medications or meeting the American Diabetes Association’s diagnostic criteria (HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, or 2-h post-load plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL).(1) Systolic and diastolic blood pressures (SBP/DBP) were the average of the 2nd and 3rd automated measurements taken after 5 minutes of quiet sitting (HEM-907XL, Omron Healthcare, Inc, Lake Forest, IL).

Statistical Methods

Participant characteristics according to sedentary screen time were described using means and percentages as appropriate. Measures of cardiac structure and function are presented as adjusted least squares means with 95% confidence intervals. Generalized linear models evaluated a test-for-trend across higher levels of sedentary screen time in progressive models with left ventricular structure and function measures as dependent variables. Cut points for sedentary screen time categories were defined a priori to isolate extreme individuals (e.g. <1 hour of screen time/day) and to reflect the sedentary time questionnaire which had an upper limit of 6 hours/day for any type of sedentary time. We detected a significant interaction between race and sedentary time for LVM (P=0<0.001), and thus report results separately by race. No gender interaction was detected for the relationship between sedentary time and LVM (P=0.184). Initial models adjusted for age, gender, height (LVM model only), center, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, and moderate and vigorous physical activity. Physical activity was included in the initial model because we were interested in determining whether sedentary screen time was associated with cardiac structure and function, independent of leisure-time moderate or vigorous physical activity.

To examine whether the association between sedentary screen time and LVM was consistent across the range of leisure-time activity, we stratified the study population into quartiles of physical activity (separately for whites and blacks) and examined the joint association of sedentary screen time and LVM within quartiles of physical activity. Quartiles had the following ranges for whites (Q1, 0–179 EU; Q2, 180–338 EU; Q3, 339–539 EU; Q4, 496–1872 EU) and for blacks (Q1, 0–92 EU; Q2, 93–223 EU; Q3, 224–408 EU, Q4, 409–1772 EU. Similarly, we stratified participants by BMI category (Normal: BMI <25.0 kg/m2, Overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and Obese: BMI≥30.0 kg/m2) and examined joint associations of screen time and LVM, separately among whites and blacks.

For variables with significant relationships in the above analyses, further models adjusted for SBP, DBP, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, and BMI. These additional adjustment variables could be in the causal pathway between sedentary screen time and cardiac structure and function; we regarded these models as possibly explanatory as opposed to deconfounding. Lastly, we performed two sensitivity analyses: 1) using total sedentary time as the independent variable and 2) excluding participants taking antihypertensive medications because they are known to affect the myocardium.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.1 (2008, StataCorp).

RESULTS

Of the 2,854 eligible participants, 1,327 (47%) were black. Median sedentary screen time was 2.7 (IQR 1.5, 3.6) hours/day among whites and 3.9 (IQR 2.3, 5.1) hours/day among blacks (P<0.001). Higher screen time was associated with higher BMI and smoking in both whites and blacks, though gradients were steeper in whites (Table 1). White men, those with less education, hypertension, and diabetes were more likely to report higher levels of sedentary screen time. SBP and DBP were positively associated with sedentary time in white adults only. Alcohol consumption was related to sedentary screen time in blacks.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics across Categories of Sedentary Screen Time by Race at Year 25 (2010–2011), CARDIA.

| Race | ≤1 hours/day | 1.1–3 hours/day | 3.1–6 hours/day | >6 hours/day | P for trend* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | White | 220 (14%) | 811 (53%) | 428 (28%) | 68 (5%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 103 (8%) | 456 (34%) | 579 (44%) | 189 (14%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | White | 50.7 ± 3.3 | 50.5 ± 3.4 | 50.8 ± 3.5 | 51.4 ± 3.0 | 0.155 |

| Black | 49.0 ± 4.2 | 49.5 ± 3.8 | 49.3 ± 3.7 | 49.1 ± 3.8 | 0.585 | |

|

| ||||||

| Men, % | White | 36% | 44% | 48% | 51% | 0.003 |

| Black | 28% | 38% | 39% | 38% | 0.806 | |

|

| ||||||

| Education, years | White | 16.4 ± 2.6 | 16.3 ± 2.4 | 15.7 ± 2.5 | 15.4 ± 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Black | 13.5 ± 2.3 | 14.4 ± 2.4 | 14.1 ± 2.5 | 14.4 ± 2.2 | 0.192 | |

|

| ||||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | White | 25.6 ± 5.4 | 27.4 ± 5.4 | 29.1 ± 5.9 | 30.1 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Black | 29.8 ± 6.8 | 31.2 ± 7.1 | 32.1 ± 7.4 | 32.2 ± 7.1 | 0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate physical activity, exercise units | White | 172 ± 104 | 162 ±110 | 153 ± 108 | 138 ± 99 | 0.008 |

| Black | 106 ± 104 | 124 ± 108 | 114 ± 106 | 115 ± 112 | 0.633 | |

|

| ||||||

| Vigorous physical activity, exercise units | White | 297 ± 243 | 232 ±217 | 202 ± 203 | 211 ± 217 | <0.001 |

| Black | 172 ± 112 | 189 ± 213 | 171 ± 200 | 159 ± 197 | 0.147 | |

|

| ||||||

| Smoker, % | ||||||

| Never | White | 67% | 66% | 55% | 60% | <0.001 |

| Former | 25% | 26% | 29% | 19% | ||

| Current | 7% | 9% | 16% | 21% | ||

| Never | Black | 59% | 66% | 63% | 53% | 0.041 |

| Former | 17% | 16% | 14% | 20% | ||

| Current | 23% | 18% | 13% | 26% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol consumption, mL/week | White | 7 (0, 21) | 7 (0, 19) | 5 (0, 22) | 4 (0, 18) | 0.314 |

| Black | 0 (0, 7) | 0 (0, 7) | 0 (0, 12) | 0 (0, 10) | 0.010 | |

|

| ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | White | 112 ± 13 | 115 ± 13 | 116 ± 16 | 119 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Black | 126 ± 16 | 123 ± 17 | 125 ± 17 | 123 ± 16 | 0.637 | |

|

| ||||||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | White | 69 ±10 | 71 ± 10 | 73 ± 11 | 75 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Black | 78 ± 11 | 77 ± 11 | 79 ± 11 | 78 ± 11 | 0.197 | |

|

| ||||||

| Taking medication to control blood pressure, % | White | 10% | 12% | 20% | 22% | <0.001 |

| Black | 39% | 32% | 37% | 33% | 0.994 | |

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes, % | White | 13% | 12% | 22% | 19% | 0.001 |

| Black | 25% | 26% | 29% | 29% | 0.290 | |

Data presented as %, mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range)

Differences across categories of screen time were evaluated using a parametric test-for-trend or a χ2 test.

Association of Sedentary Screen Time with Left Ventricular Structure and Function

Among whites, higher sedentary screen time was associated with higher LVM (P for trend<0.011), LVMi (P for trend<0.001), mass-to-volume ratio (P for trend=0.002), and relative wall thickness (P for trend 0.049) independent of demographic characteristics, height (LVM only), alcohol, smoking, and moderate and vigorous physical activity (Model 1 in Table 2). Other measures (EDV index, ESV index, ejection fraction, stroke volume) were not associated with sedentary screen time among whites. No associations between sedentary screen time and any measures of left ventricular structure or function were observed in blacks (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Adjusted Mean (95% Confidence Interval) Measures of Left Ventricular Structure and Function with Progressive Multivariate Adjustment across Sedentary Screen Time Categories in Whites (n=1,527) at Year 25 (2010–2011), CARDIA.

| ≤1 hours/day (n=220) | 1.1–3 hours/day (n=811) | 3.1–6 hours/day (n=428) | >6 hours/day (n=68) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular mass, g | |||||

| Model 1* | 158 (153, 164) | 161 (158, 165) | 167 (163, 171) | 175 (166, 184) | <0.001 |

| Model 2† | 163 (158, 169) | 165 (161, 168) | 169 (165, 172) | 175 (166, 184) | 0.008 |

| Model 3‡ | 168 (164, 174) | 167 (165, 170) | 168 (165, 172) | 173 (165, 181) | 0.503 |

| Left ventricular mass index, g/m2.7 | |||||

| Model 1* | 37.1 (35.8, 38.5) | 37.9 (37.2, 38.8) | 39.5 (38.5, 40.5) | 41.3 (39.1, 43.6) | <0.001 |

| Model 2† | 38.4 (37.1, 39.8) | 38.8 (37.9, 39.6) | 40.0 (39.1, 41.0) | 41.4 (39.3, 43.6) | 0.002 |

| Model 3‡ | 39.9 (38.7, 41.1) | 39.4 (38.7, 40.2) | 40.0 (39.2, 40.9) | 41.0 (39.0, 43.0) | 0.303 |

| Mass-to-volume ratio, g/mL | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.294 (0.284, 0.304) | 0.305 (0.298, 0.311) | 0.307 (0.300, 0.315) | 0.327 (0.310, 0.344) | 0.002 |

| Model 2 | 0.300 (0.290, 0.310) | 0.309 (0.303, 0.315) | 0.310 (0.303, 0.317) | 0.327 (0.311, 0.344) | 0.016 |

| Model 3 | 0.305 (0.295, 0.315) | 0.311 (0.305, 0.317) | 0.310 (0.305, 0.317) | 0.326 (0.310, 0.343) | 0.125 |

| Relative Wall Thickness | |||||

| Model 1 | 0.335 (0.326, 0.344) | 0.344 (0.339, 0.350) | 0.342 (0.336, 0.348) | 0.360 (0.345, 0.375) | 0.049 |

| Model 2 | 0.339 (0.330, 0.348) | 0.346 (0.341, 0.352) | 0.343 (0.337, 0.350) | 0.360 (0.345, 0.375) | 0.144 |

| Model 3 | 0.341 (0.332, 0.350) | 0.347 (0.342, 0.353) | 0.343 (0.337, 0.350) | 0.360 (0.345, 0.375) | 0.267 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic volume index, mL/m | |||||

| Model 1 | 75.0 (72.7, 77.3) | 74.2 (72.8, 75.5) | 76.7 (75.1, 78.3) | 75.6 (71.9, 79.4) | 0.090 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, mL/m | |||||

| Model 1 | 23.1 (21.8, 24.4) | 22.7 (22.0, 23.5) | 23.2 (22.5, 24.3) | 23.1 (20.9, 25.2) | 0.529 |

| Ejection fraction, % | |||||

| Model 1 | 69.8 (68.7, 70.8) | 69.5 (68.9, 70.1) | 69.8 (69.0, 70.5) | 69.6 (67.8, 71.3) | 0.955 |

| Stroke volume, mL | |||||

| Model 1 | 89.1 (86.3, 91.8) | 88.1 (86.5, 89.8) | 90.9 (88.9, 92.9) | 89.6 (85.0, 94.3) | 0.136 |

Model 1 adjusts for age, sex, height (left ventricular mass (g) only), center, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, moderate and vigorous physical activity;

Further adjusted models are presented for measures with significant trends in Model 1. Model 2 adds antihypertensive medication use, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and diabetes;

Model 3 adds body mass index

Table 3.

Adjusted* Mean (95% Confidence Interval) Measures of Left Ventricular Structure and Function with Progressive Multivariate Adjustment across Sedentary Screen Time Categories in Blacks (n=1,327) at Year 25 (2010–2011), CARDIA.

| ≤1 hours/day (n=103) | 1.1–3 hours/day (n=456) | 3.1–6 hours/day (n=579) | >6 hours/day (n=189) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular mass, g | 175 (165, 184) | 176 (171, 181) | 179 (174, 183) | 177 (170, 184) | 0.422 |

| Left ventricular mass index, g/m2.7 | 41.5 (39.1, 43.9) | 41.6 (40.3–42.8) | 42.2 (41.1, 43.4) | 41.7 (39.9, 43.5) | 0.613 |

| Mass-to-volume ratio, g/mL | 0.334 (0.314, 0.354) | 0.335 (0.325, 0.345) | 0.338 (0.329, 0.348) | 0.331 (0.317, 0.346) | 0.950 |

| Relative Wall Thickness | 0.366 (0.350, 0.381) | 0.368 (0.360, 0.376) | 0.371 (0.363, 0.378) | 0.366 (0.354, 0.377) | 0.830 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic volume index, mL/m | 74.6 (71.3, 78.0) | 74.2 (72.4, 75.9) | 75.1 (73.5, 76.8) | 75.3 (72.8, 77.7) | 0.408 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, mL/m | 23.2 (21.3, 25.0) | 22.8 (21.9, 23.8) | 23.4 (22.5, 24.3) | 23.2 (21.8, 24.5) | 0.572 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 69.3 (67.6, 70.9) | 69.4 (68.5, 70.2) | 69.3 (68.5, 70.1) | 69.6 (68.3, 70.8) | 0.842 |

| Stroke volume, mL | 87.6 (83.4, 91.9) | 87.5 (85.3, 89.6) | 88.4 (86.4, 90.5) | 89.4 (86.3, 92.5) | 0.286 |

Adjusted for age, sex, height (left ventricular mass (g) only), center, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, and moderate and vigorous physical activity.

Table 2 also displays further adjustment (Models 2 and 3) of least square means for LVM, LVMi, mass-to-volume ratio, and relative wall thickness among white adults only. These measures of left ventricular structure each displayed significant associations with sedentary screen time in minimally adjusted models. The associations largely persisted following additional covariate adjustment for use of antihypertensive medication, SBP, DBP, and diabetes (Model 2), but became nonsignificant after further adjustment for BMI (Model 3).

Joint Association of Sedentary Screen Time and Physical Activity or Body Mass Index with Left Ventricular Mass

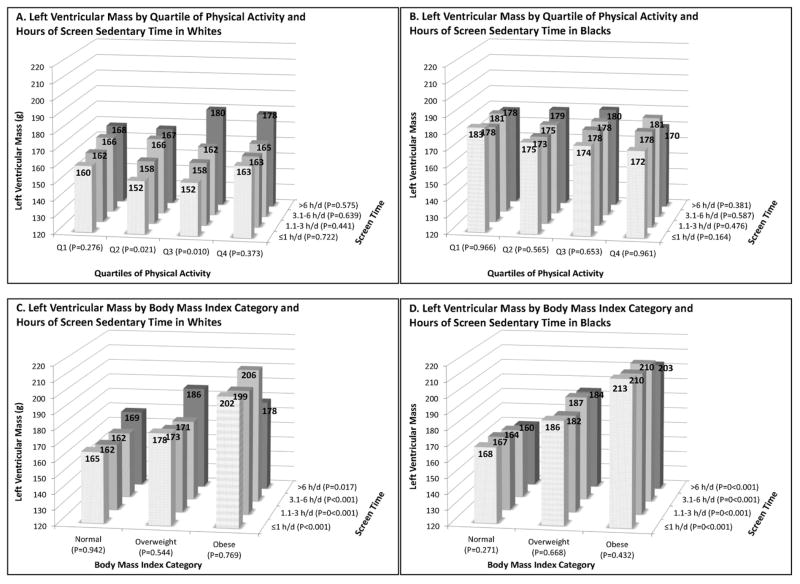

Figure 1(A and B) depicts the joint association of sedentary screen time category and leisure-time physical activity quartile in whites and blacks, adjusted for age, sex, height, center, education, smoking, and alcohol consumption (Model 1 covariates). Among whites, adjusted mean LVM was higher with each higher category of sedentary screen time in each quartile of physical activity, although this trend was only significant for quartiles 2 and 3 (P for trend = 0.021 and 0.010, respectively). Among blacks, no associations were observed between sedentary screen time and LVM within any of the physical activity quartiles. No significant associations were observed across physical activity quartiles within sedentary screen time categories for whites or blacks.

Figure 1.

Joint Associations between Left Ventricular Mass (g) with Sedentary Screen Time Categories and Quartiles of Physical Activity (whites (A) and blacks (B)) or Body Mass Index (whites (C) and blacks (D)). Displayed as adjusted mean left ventricular mass (g) across adjusted for age, sex, height center, education, smoking, physical activity (C and D only) and alcohol consumption. P-values test for trend across opposite axis within category.

Among BMI categories, screen time was not associated with LVM in whites (Figure 1, C) or blacks (Figure 1, D). However, a similar and strong relationship where LVM was higher in higher BMI categories was observed in both whites and blacks.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sedentary screen time and total sedentary time were highly correlated (r=0.78, P<0.001) with screen time accounting for an average of 47 ± 17% of total sedentary time. Results were similar when we repeated all analyses substituting total sedentary time as the outcome (data not shown). Findings were also similar when we excluded participants who reported using antihypertensive medications (n=685, 24%).

DISCUSSION

In this community-based sample of middle-aged adults free from overt clinical cardiovascular disease, we found that higher sedentary screen time, independent of moderate and vigorous leisure-time physical activity, was associated with several measures of left ventricular structure in whites but not blacks. These measures of left ventricular structure included higher LVM, LVMi, mass-to-volume ratio, and relative wall thickness. These associations largely persisted following adjustment for potential intermediate comorbidities, but were explained by further adjustment for overall adiposity.

Sedentary Screen Time, Obesity, and Left Ventricular Structure

To our knowledge, this report is the first investigation of relationships between sedentary time and left ventricular structure and function and gives insight into pathways through which sedentary behavior may impact cardiovascular outcomes and mortality. In exercise training studies, exercise induces favorable adaptations such as increased LVM, EDV, ejection fraction and stroke volume.(5, 31) In the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, intentional exercise was associated with increased LVM, EDV, and stroke volume and these trends were nonlinear with an increased gradient at lower levels of physical activity.(36) In fact, changes to left ventricular structure and function have been hypothesized as an additional pathway through which exercise training improves cardiovascular risk beyond traditional risk factors.(21, 25) On the other hand, bed rest or deconditioning studies, which could be interpreted as extreme exposure to sedentary behavior, induce a decrease in LVM, mean wall thickness, EDV, and stroke volume, presumably as a physiological response to a decreased myocardial load.(28, 33) We observed a consistent association of higher LVM with higher screen time in whites across the spectrum of physical activity levels, though most strongly in persons just below (Q2) or just above (Q3) leisure-time physical activity recommendations. We did not detect a lower LVMi with higher sedentary screen time in whites or blacks as might have been expected given the effects observed in bed rest studies and a recent study comparing adults with intellectual disabilities to controls.(38) It seems likely that a more extreme gradient in sedentary screen time would be needed to observe such trends.

Among whites, our results suggest that sedentary screen time potentially contributes to adverse cardiac remodeling through its association with comorbidities (hypertension and diabetes) and, to a greater extent, overall adiposity. All measures in our study were assessed concurrently, so we are limited in causal inference, but the most plausible interpretation of our findings is that sedentary screen time contributes to obesity and obesity-related comorbidities, which in turn may lead to increased LVM, LVM indexed to height2.7 and volume, and relative wall thickness. This pathway is suggested by the disappearance of an association between screen time and left ventricular structural measures after stratification by BMI (Figure 1C) or after multivariate adjustment for BMI (Table 2). Further prospective studies are needed to establish the temporal pattern of sedentary screen time, obesity, and left ventricular structure. Despite this, and taken together with the growing evidence that sedentary time is detrimental to health, the public health community should consider the establishment of sedentary screen time recommendations to augment current physical activity recommendations.

We observed no evidence of an association between sedentary screen time and left ventricular structure in blacks. Since the relationships in whites were explained by obesity and comorbidities, we believe this lack of association in blacks likely stems from the lack of association between sedentary screen time and comorbidities (blood pressure, diabetes) and the weaker relationship of sedentary time with BMI among blacks (Table 1). The disconnect between sedentary time and cardiovascular risk factors among blacks, while not physiologically intuitive, is consistent with previous studies.(15, 23) In NHANES 2003–2006, Healy and colleagues found that higher accelerometry-derived sedentary time was related to worse cardiovascular risk factors in whites (waist circumference, SBP, HDL cholesterol, insulin and insulin sensitivity), but was associated with lower waist circumference and was unrelated to other cardiovascular risk factors among blacks.(15) An analysis of 15,349 9th–12th graders from the Youth Risk Behavioral Survey found that more television watching was associated with greater odds of being overweight in whites but not blacks.(23) Our findings extend evidence of a race interaction within the relationship between sedentary time and cardiovascular risk to a subclinical marker of cardiovascular disease. In our study, the lack of an association among black adults could be due to a higher amount of sedentary screen time coupled with reduced leisure-time physical activity. These distributional differences, specifically lack of range, could limit the ability to observe effects of sedentary time on left ventricular measures in blacks. While the source of the interaction, be it differential distributions, unmeasured confounding, genetic, or cultural factors, is unclear, studies investigating the effect of sedentary time on cardiovascular outcomes in blacks is an area in need of further research.

Limitations

While our results are strengthened by the sample size, design, and extensive assessments conducted by CARDIA, several limitations of our analysis elicit cautious interpretation of results. First, as previously mentioned, the current study was cross-sectional and thus the temporal sequence of sedentary lifestyle and left ventricular structure and function cannot be established. Second, the small age range (43–55 years) may limit generalizability of our results to younger or older adults. Third, sedentary screen time was assessed by self-report and a review(4) along with two more recent reports(24, 30) of the measurement properties of self-reported sedentary time have identified respectable reliability but important limitations in validity. For example, overlapping questions (e.g. a person could be watching television and using a computer simultaneously) could overestimate sedentary time, social desirability bias could underestimate sedentary time, and the best criterion measure, particularly for domain-specific sedentary time, remains unclear. In response to these limitations, we tested for trends across screen-time categories which likely classified most individuals in the extremes and resisted the potential for undue influence by outliers. Similar limitations of self-report apply to the measurement of physical activity,(32) which was an important covariate in our analysis. Lastly, measurement by echocardiography, though cost-effective for large epidemiologic studies, has been found to overestimate LVM compared to magnetic resonance imaging.(13) However, this limitation is more of a concern for repeated measures or individual risk stratification,(13) and we expect that the associations we observed were, if anything, attenuated as a result of such measurement error. Echocardiography also cannot assess expansion of the extracellular matrix in the myocardium, which reflects pathologic (vs. adaptive) left ventricular hypertrophy,(35) is quantifiable by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, is a potent predictor of mortality,(39) and could shed light on the relationships between sedentary time, physical activity, and cardiovascular outcomes. Also, speckle-tracking echocardiography, which measures left ventricular deformation, identifies early cardiac dysfunction, and has been shown to distinguish between pathologic and adaptive left ventricular hypertrophy in exercise studies,(11) could be helpful for defining how sedentary behavior affects left ventricular structure and function. Future investigations using these or other more sensitive subclinical measures may yet detect associations between sedentary time and left ventricular function.

Implications

Higher sedentary screen time was linked to a larger left ventricle in whites, and this relationship was observed even among individuals meeting or exceeding moderate/vigorous physical activity recommendations. On the other hand, the lack of a relationship between sedentary screen time and left ventricular structure and function observed among black adults in the current study highlights the need for further investigation. Future research should continue to study relationships between sedentary behavior and cardiovascular outcomes using more discriminating measures of cardiac structure and function and with special attention to potential effect modification by race.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support

This study was supported by grants from the Coordinating Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham (N01-HC-95095); the Field Center, University of Alabama, (N01-HC-48047); the Field Center and Diet Reading Center, University of Minnesota (N01-HC-48048); Northwestern University Field Center (N01-HC-48049); and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (N01-HC-48050) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The CARDIA ECG Ancillary Study was supported by Grant R01-HL-086792 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The results of this study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM. The authors would like to thank Dr. Anderson Armstrong for his invaluable contributions as an external reviewer of this manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33 (Suppl 1):S62–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor. American Time Use Survey - 2011 Results. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chirinos JA, Segers P, De Buyzere ML, Kronmal RA, Raja MW, De Bacquer D, Claessens T, Gillebert TC, St John-Sutton M, Rietzschel ER. Left ventricular mass: allometric scaling, normative values, effect of obesity, and prognostic performance. Hypertension. 2010;56(1):91–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark BK, Sugiyama T, Healy GN, Salmon J, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Validity and reliability of measures of television viewing time and other non-occupational sedentary behaviour of adults: a review. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox ML, Bennett JB, 3rd, Dudley GA. Exercise training-induced alterations of cardiac morphology. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61(3):926–31. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.3.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Simone G, Daniels SR, Kimball TR, Roman MJ, Romano C, Chinali M, Galderisi M, Devereux RB. Evaluation of concentric left ventricular geometry in humans: evidence for age-related systematic underestimation. Hypertension. 2005;45(1):64–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150108.37527.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57(6):450–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Jr, Liu K, Savage PJ. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–16. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardin JM, Brunner D, Schreiner PJ, Xie X, Reid CL, Ruth K, Bild DE, Gidding SS. Demographics and correlates of five-year change in echocardiographic left ventricular mass in young black and white adult men and women: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(3):529–35. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardin JM, Wagenknecht LE, Anton-Culver H, Flack J, Gidding S, Kurosaki T, Wong ND, Manolio TA. Relationship of cardiovascular risk factors to echocardiographic left ventricular mass in healthy young black and white adult men and women. The CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Circulation. 1995;92(3):380–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geyer H, Caracciolo G, Abe H, Wilansky S, Carerj S, Gentile F, Nesser HJ, Khandheria B, Narula J, Sengupta PP. Assessment of myocardial mechanics using speckle tracking echocardiography: fundamentals and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(4):351–69. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.02.015. quiz 453–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gidding SS, Carnethon MR, Daniels S, Liu K, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sidney S, Gardin J. Low cardiovascular risk is associated with favorable left ventricular mass, left ventricular relative wall thickness, and left atrial size: the CARDIA study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(8):816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gjesdal O, Bluemke DA, Lima JA. Cardiac remodeling at the population level--risk factors, screening, and outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(12):673–85. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(5):1454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EA, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003–06. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(5):590–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healy GN, Wijndaele K, Dunstan DW, Shaw JE, Salmon J, Zimmet PZ, Owen N. Objectively measured sedentary time, physical activity, and metabolic risk: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):369–71. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs DR, Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and Reliability of Short Physical Activity History: Cardia and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 1989;9(11):448. doi: 10.1097/00008483-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karason K, Wallentin I, Larsson B, Sjostrom L. Effects of obesity and weight loss on left ventricular mass and relative wall thickness: survey and intervention study. BMJ. 1997;315(7113):912–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7113.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Craig CL, Bouchard C. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(5):998–1005. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee IM. Physical activity and cardiac protection. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(4):214–9. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181e7daf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(22):1561–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowry R, Wechsler H, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Kann L. Television viewing and its associations with overweight, sedentary lifestyle, and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables among US high school students: differences by race, ethnicity, and gender. J Sch Health. 2002;72(10):413–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb03551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall AL, Miller YD, Burton NW, Brown WJ. Measuring total and domain-specific sitting: a study of reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(6):1094–102. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mora S, Cook N, Buring JE, Ridker PM, Lee IM. Physical activity and reduced risk of cardiovascular events: potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation. 2007;116(19):2110–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman GJ, Schmid BA, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Patrick K. Psychosocial and environmental correlates of adolescent sedentary behaviors. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):908–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Nieminen MS, Snapinn S, Harris KE, Aurup P, Edelman JM, Wedel H, Lindholm LH, Dahlof B. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment and the prediction of major cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2343–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perhonen MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG, Zerwekh JE, Peshock RM, Weatherall PT, Levine BD. Cardiac atrophy after bed rest and spaceflight. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(2):645–53. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg DE, Norman GJ, Wagner N, Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Sallis JF. Reliability and validity of the Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ) for adults. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(6):697–705. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro LM, Smith RG. Effect of training on left ventricular structure and function. An echocardiographic study. Br Heart J. 1983;50(6):534–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.50.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shephard RJ. Limits to the measurement of habitual physical activity by questionnaires. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(3):197–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.3.197. discussion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spaak J, Montmerle S, Sundblad P, Linnarsson D. Long-term bed rest-induced reductions in stroke volume during rest and exercise: cardiac dysfunction vs. volume depletion. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(2):648–54. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01332.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Dunstan DW. Screen-based entertainment time, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular events: population-based study with ongoing mortality and hospital events follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(3):292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(1):215–62. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turkbey EB, Jorgensen NW, Johnson WC, Bertoni AG, Polak JF, Roux AV, Tracy RP, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. Physical activity and physiological cardiac remodelling in a community setting: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Heart. 2010;96(1):42–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.178426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2008. pp. 21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vis JC, de Bruin-Bon RH, Bouma BJ, Backx AP, Huisman SA, Imschoot L, Mulder BJ. ‘The sedentary heart’: physical inactivity is associated with cardiac atrophy in adults with an intellectual disability. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158(3):387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG, Testa SM, Klock AM, Aneizi AA, Shakesprere J, Kellman P, Shroff SG, Schwartzman DS, Mulukutla SR, Simon MA, Schelbert EB. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012;126(10):1206–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]