Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether oral self-care function mediates the associations between cognitive impairment and caries severity in community-dwelling older adults.

Background

Cognitive impairment significantly affects activities of daily living and compromises oral health, systemic health and quality of life in older adults. However, the associations among cognitive impairment, oral self-care capacity and caries severity remain unclear. This increases difficulty in developing effective interventions for cognitively impaired patients.

Materials and methods

Medical, dental, cognitive and functional assessments were abstracted from the dental records of 600 community-dwelling elderly. 230 participants were selected using propensity score matching and categorised into normal, cognitive impairment but no dementia (CIND) and dementia groups based on their cognitive status and a diagnosis of dementia. Multivariable regressions were developed to examine the mediating effect of oral self-care function on the association between cognitive status and number of caries or retained roots.

Results

Cognitive impairment, oral self-care function and dental caries severity were intercorrelated. Multivariable analysis showed that without adjusting for oral self-care capacity, cognition was significantly associated with the number of caries or retained roots (p = 0.003). However, the association was not significant when oral self-care capacity was adjusted (p = 0.125). In contrast, individuals with impaired oral self-care capacity had a greater risk of having a caries or retained root (RR = 1.67, 95% CI 1.15, 2.44).

Conclusion

Oral care capacity mediates the association between cognition and dental caries severity in community-dwelling older adults.

Keywords: Dental caries, Older adults, Community-dwelling, Oral Self-care function, Cognitive impairment

Introduction

Cognitive impairment is a serious public health issue affecting 8.8 million (35%) Americans aged 71 and older1,2 and significantly compromising oral health, systemic health and quality of life in older adults. It refers to the loss of higher level reasoning, memory loss, learning disabilities, attention deficits, decreased intelligence, and other reductions in mental functions. Many factors, including dementia, adverse effects from medications, trauma, infections, metabolic disturbances, and psychiatric illness, may contribute to cognitive impairment in older adults3-7. Among the etiological factors, dementia, a neurodegenerative disorder usually occurring in late life, is the most common cause of cognitive impairment3. Dementia is highly prevalent in older adults, affecting 13.9% of Americans aged 71 and older1. It compromises a patient's capacity to perform daily functions, increases disability9, and leads to increased health care costs10,11, all of which have a wide-ranging impact on individuals, families and healthcare systems.

As one of the most noticeable sequelae of dementia, functional impairment is highly prevalent in cognitively-impaired older adults12-14. It is also an essential component of diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease and other dementing illnesses8,15. Declined cognitive function not only impairs an individual's capacity for instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), but also affects basic activities of daily living (ADLs) including feeding, toileting, bathing, grooming, ambulating, and dressing12-14. Agüero-Torres et al. found that demented subjects had a greater disability prevalence on all specific IADLs and ADLs items than cognitively impaired subjects who, in turn, had greater disability than non-demented subjects14. Cognitive impairment also compromises dentally-related functions. Demented patients with attention deficit are highly distractible and may have difficulty staying on track long enough to complete oral hygiene care. Individuals with impaired prospective memory may have difficulty in remembering removing and cleaning dentures at bedtime. Functional impairment not only affects quality of life16 and increases caregiver's burden16-19, but it also increases risk for long-term care placement17,20 and death21 in the elderly population.

Evidence suggests that cognition, function and oral health may be intercorrelated. Although their cognitive impairment has not yet met the diagnostic criteria of dementia, individuals with mild cognitive impairment have poorer oral hygiene, a high score of gingivitis and more decayed root surfaces than those with intact cognition22. Compared to those without dementia, community-dwelling older adults with cognitive impairment experienced more coronal and root caries, had more missing teeth and a higher proportion of periodontitis sites, were less likely to use dentures, and had a greater prevalence of denture-related soft tissue lesions23-25. Annual caries increment was also higher in those with dementia26, 27. While oral health is associated with cognitive impairment, it is also correlated with daily function28-30. Functional capacity is the most predictive factor for dental health in older adults after adjusting for chronic medical conditions and other factors28. Older adults with functional limitation not only have a significantly higher risk of root caries30, they are also less likely to use dental services than those without functional limitation29. These findings indicate that poor oral health is a serious issue in older adults with cognitive and functional impairment. Effective measures need to be taken to prevent and manage oral diseases and their subsequent impacts on systemic health and quality of life in these vulnerable individuals.

While multiple studies have been conducted to compare oral health in community-dwelling older adults with different cognitive and functional statuses24-31, how cognitive function, oral hygiene care capacity and dental caries severity correlate to each other remains unclear. A better understanding of the roles of cognitive impairment and functional disability in dental caries severity in older adults can help dental professionals better address their oral health needs, develop patient-specific, effective strategies to prevent and manage dental caries, and therefore improve clinical outcome and quality of care for this challenging population. For this reason, we conducted this study to explore the association between cognitive function, capacity to perform oral hygiene and caries severity in community-dwelling older adults. We hypothesized that as a result of cognitive impairment, loss of oral self-care function mediates the relation between cognitive impairment and dental caries severity in cognitively-impaired patients.

Material and Methods

The present study was a cross-sectional study based on pre-existing dental records. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol.

Study clinic and study population

The study clinic was a non-profit community-based geriatric dental clinic jointly operated by the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry and the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation in St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. During the study period (10/23/1999-12/31/2006), 1626 older adults received dental care as new patients in the study clinic. Among them, 600 were community-dwelling. These patients consisted of the study population of the present study and were all included in the analysis.

Data collection

All the study data were originally collected for the purpose of patient care during the new patient exam, which included comprehensive review of medical history and medications, oral examination and cognitive and functional assessments. During the present study, these data were abstracted from dental records for the analysis.

The medical history of all 600 community-dwelling patients was reviewed and abstracted from their dental records during the present study.. For patients from group homes or an adult daycare program, their medical history was directly transferred from medical records provided by the group homes or the adult daycare program. For community-dwelling patients, their medical history was collected using a structured questionnaire during the new patient exams. This information was provided by patients or reliable family members when patients were cognitively impaired or functionally dependent.

The outcome of interest was dental caries severity (e.g., number of carious teeth, including decayed retained roots). Caries assessment was completed for all the patients when they first presented to the clinic. Full mouth radiographs were also taken for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment planning. During the present study, we reviewed patients' dental records and radiographs. Based on dental clinical chartings and radiographs, carious teeth and decayed retained roots were identified from dental records. The following oral health measures were also reviewed and recorded as covariates: 1) number of teeth; 2) number of teeth with restorations; 3) oral hygiene and gingival inflammation and 4) use of a removable dental prosthesis.

The exposures, cognitive and functional status, were also abstracted from dental records. Cognitive and functional assessments were completed when patients first arrived to the clinic. As part of the comprehensive new patient exam, dentists assessed patients' cognition from three different aspects: memory, orientation and judgment using a set of subjective approaches that are commonly used in geriatric dental practice33, including 1) administering part of the MMSE; 2) asking caregiver about the cognitive status of the patients; 3) assessing cognitive status through verbal communication; and 4) asking the patient to repeat and/or demonstrate clinical instructions. Based on cognitive assessments, we categorized patients into four categories, not impaired, questionable, slightly impaired, moderately/severely impaired.

During the new patient exam, the dental providers in the study clinic also used a set of subjective and objective approaches collectively to assess capacity to perform oral hygiene. Based on the caregiver's assessment (cognitively-impaired patients only), cognitive status, range of motion of the upper extremity and manual dexterity, oral hygiene at arrival and level of cooperation, dentists classified patients' oral self-care function into the following groups: self-sufficient, needs supervision or assistance, and won't cooperate.

Other covariates such as medications, physical mobility, disruptive behaviors, cooperation for dental care and language impairment were also abstracted from dental records. Sociodemographics (e.g., age, gender, dental insurance coverage) were abstracted from the clinical information system used in the study clinic.

Selection of study participants

Based on medical history and cognitive assessment available in dental records, the 600 community-dwelling patients were categorized into three groups: 492 without cognitive impairment (normal group); 57 with cognitive impairment but no dementia (CIND group); and 51 with dementia (dementia group). Individuals with dementia were identified based on medical history. Individuals were considered to have dementia if they had the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, codes of 290. ×, 294.1, or 331.233 or a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, other types of dementia or chronic brain syndrome. The review of medical records also found that most patients with cognitive impairment but without dementia had a history of stroke, psychiatric illnesses (e.g., Schizophrenia) or developmental disorders (e.g., Down syndrome).

Preliminary analysis showed a large variation in the baseline characteristics among the three groups. To address the large differences in sample size and baseline characteristics among the study population, the propensity score matching (PSM) method was used34,35. The PSM has been widely used in clinical research to address selection bias and is appropriate for situations in which the group of interest differs substantially from the control group. Selecting a subset of the control group similar to the group of interest is difficult because subjects must be compared on many baseline characteristics. The crucial difference of PSM from conventional matching is that PSM matches subjects in the study group to one or more subjects in the control group based on a propensity score rather than multiple variables. Propensities were the log proportional odds of a specific cognitive status given the selected baseline characteristics (e.g., age, gender, number of medical conditions, Sum of Anticholinergic Drug Scale (ADS)36 scores of current medications and physical mobility) without individual intercepts. Then a type of caliper propensity matching was used to match 3 cognitively-intact patients to every cognitively-impaired patient and to every dementia patient. Using this 3-1-1 matching technique, a total of 230 community-dwelling patients, including 138 cognitively-intact, 46 cognitively-impaired and 46 demented patients, were selected as study participants.

Data analysis

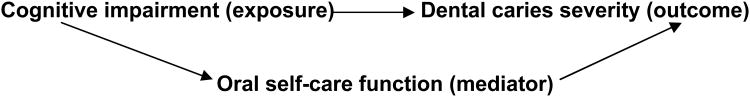

The objective of the study was to determine if the capacity to perform oral hygiene mediates the association between cognitive impairment and dental caries (Figure 1). Evidence shows that cognitive impairment, functional loss and dental caries are intercorrelated12-14, 23-25, 30. From a clinical perspective, loss of oral care function is more likely to be a result, rather than a cause, of cognitive impairment among cognitively-impaired persons. Therefore, in theory, loss of oral self-care ability may serve as a mediator in the pathway between cognitive impairment and dental caries in older adults with cognitive impairment. To test our hypothesis, univariate analyses were first completed to examine the associations among cognitive impairment, capacity to perform oral hygiene and dental caries severity. Significant intercorrelations were found among these three factors. Multivariable analyses were then conducted to test the mediating effect of functional impairment on the relationship between cognitive impairment and dental caries severity. Two negative binomial models were developed for this purpose. The first model examined the impact of cognitive impairment on the outcome of interest, number of carious teeth or retained roots, without considering the capacity to perform oral hygiene. The baseline model started with cognitive status, age, genderand other covariates (Table 2). The second model examined the association between cognitive impairment and the number of carious teeth or retained roots while adjusting for the capacity to perform oral hygiene and the covariates. Covariates with P values greater than 0.05 were removed during model selection, given that removing these variables did not substantially change the coefficients of the exposures of interest.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the mediating effect of oral self-care function on the association between cognitive impairment and dental caries severity.

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of the intercorrelations among cognitive impairment, oral self-care function and dental caries severity.

| Parameter | Model 1c | Model 2c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| RR (95% CI) | P-value | RR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Cognitive status | Non-impaireda | 1.00 | <0.01 | 1.00 | 0.12 |

|

| |||||

| Impaired | 1.66(1.13, 2.46) | 1.45(0.98, 2.15) | |||

|

|

|

||||

| Demented | 1.82(1.23, 2.70) | 1.37(0.89, 2.11) | |||

|

| |||||

| Capacity to perform oral hygiene careb | Self-sufficienta | - | - | 1.00 | <0.01 |

|

|

|

||||

| Need Supervision or Help | - | 1.67(1.15, 2.44) | |||

n, describes the total number of people with a certain characteristic.

Reference groups.

Patients who were uncooperative to oral care was dropped from the analysis due to extremely small sample size.

adjusted for covariates: age, gender, dental insurance, number of medical conditions, total anticholinergic side effect of medications, cooperative to care, physical mobility, number of teeth, number of filled teeth, Calculus/Plaque/Gingival bleeding and use of a removable dental prosthesis.

The propensities and actual data analysis were completed using SAS 9.2. Propensity score matching was conducted using MATLAB 7.4.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

The mean age of this population was 72.9 years. Patients with cognitive impairment but no dementia (CIND, mean age=78.3) and patient with dementia (mean age=79.3) were older than the normal group (mean age=71.6, P<0.001). About two-third of the patients in each group were female (P=0.95). Seventy-two percent of the patients in the CIND group had dental insurance, significantly higher than those in the normal group (57%) and demented group (57% and 45%, respectively, P=0.02).

Correlation between cognitive impairment and oral self-care capacity

The univariate analysis revealed that cognitive status was associated with capacity to perform oral hygiene (Table 1). The vast majority of the patients in the normal group were capable of performing oral hygiene independently. A considerable proportion of the patients with cognitive impairment (43% in CIND group and 66% in dementia group) needed supervision/help to maintain oral hygiene, significantly higher than that of the normal group (P<0.001).

Table 1. Association between cognitive impairment and capacity to perform oral hygiene care.

| Non-Impaired | Impaired | Demented | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N=492 | N=57 | N=51 | |||

| Capacity to perform oral hygiene (%) | Self Sufficient | 95.7 | 57.1 | 33.4 | <.001a |

|

| |||||

| Need Supervision or Help | 4.3 | 42.9 | 56.9 | ||

|

| |||||

| Patient won't Cooperate | 0 | 0 | 9.8 | ||

n, describes the total number of people with a certain characteristic.

Fisher's Exact Test.

Correlation between cognitive impairment and dental caries severity

Dental caries severity was significantly associated with cognitive impairment. Regardless of dementia, caries were highly prevalent in community-dwelling participants with cognitive impairment. On average, the patients in the CIND and dementia groups had 6.1 and 5.5 teeth with caries or retained roots at arrival, respectively, which were significantly higher than 3.3 in the normal group (P<0.001). Further analysis shows that 42.9% of the patients in the CIND and 37.3% of the patients in the dementia groups arrived with at least 5 carious teeth or retained roots, remarkably higher than that of the normal group (25.1%, P=0.01).

Correlation between oral self-care capacity and dental caries severity

Meanwhile, the capacity to perform oral hygiene was also significantly associated with the outcome of interest, number of carious teeth or retained roots. On average, elderly patients who needed help on oral hygiene had 6.7 carious teeth or retained roots, twice of that among functionally independent patients (mean=3.3, P<0.001).

Multivariate analysis of the intercorrelations among cognitive impairment, oral care capacity and dental caries severity

Multivariate analyses were also completed to study the intercorrelations among cognitive impairment, oral care capacity and dental caries severity (Table 2). Model 1 shows that while the capacity to perform oral hygiene was not included in the model, cognitive status was significantly associated with the outcome of interest, number of carious teeth or retained roots, in the community-dwelling participants after adjusting for age, gender and other covariates. Participants in the CIND and dementia groups had 1.7 (95% CI: 1.13, 2.46) and 1.8 (95% CI: 1.23, 2.70) times more likely to have a carious tooth or retained root, respectively, than the normal group. While the capacity to perform oral hygiene was adjusted for, this association was no longer significant. On the other hand, participants who lost their ability to perform oral hygiene had 1.7 (95% CI: 1.15, 2.44) times greater risk of having a carious tooth or retained root than those who were self-sufficient. These results clearly demonstrate that the capacity to perform oral hygiene mediated the relationship between the cognitive impairment and dental caries severity.

Discussion

The present study examined the intercorrelations among cognitive function, capacity to perform oral hygiene and dental caries severity in community-dwelling older adults. The results show that 1) cognitive status and capacity to perform oral hygiene was highly correlated; 2) they were both associated with dental caries severity; 3) without adjusting for the capacity to perform oral hygiene, cognitive status was significantly associated with dental caries severity, the amount of carious teeth or retained roots, after adjusting for other factors; however, 4) when the capacity to perform oral hygiene was adjusted for, the association between cognitive status and dental caries severity was insignificant. In turn, participants who lost their ability to maintain oral hygiene experienced a higher risk of having a carious condition than those who were self-sufficient. These findings suggest that an impaired capacity to perform oral hygiene may mediate the association between cognitive impairment and increased severity of dental caries in older adults with cognitive impairment.

Loss of ability to function, including oral self care function, is a common complication of cognitive impairment. Impaired capacity to perform oral hygiene may result from deficits in multiple cognitive domains. For example, procedural memory is a type of long-term memory of how to execute the integrated procedures involved in both cognitive and motor skills37. When impaired, patients may lose their ability to brush teeth, a skill that is developed through learning and practice in early life. Executive function, a cognitive ability that involves the planning and execution of goal-directed behaviors, abstract reasoning, and judgment38, is highly associated with dental self-care39-41. Impaired executive function compromises the ability to initiate, plan, sequence and carry out complex tasks such as brushing teeth or following instructions to remove and clean dentures at bedtime, resulting in poor oral hygiene and an increased risk of oral disease. Additionally, individuals with apraxia —inability to perform a purposeful movement— may also experience difficulties in performing oral hygiene, despite having the physical strength and intellectual thought and desire to do so42. As a result of these multiple cognitive domain deficits, older adults with cognitive impairment gradually lose their oral care capacity, resulting in poor oral and/or denture hygiene.

Diminished oral hygiene, together with a lack of sufficient caregiver support and lack of regular dental care, increases the risk of dental caries in cognitively-impaired patients. As a result, dental caries are highly prevalent in older adults with functional impairment24,26,28-30. Evidence shows that among community-dwelling older adults with dementia, coronal and root surface caries experiences were significantly higher in participants with more functional dependency and those who needed assistance with oral hygiene care24. A similar finding was also revealed in the present study. Regardless of cognitive impairment, elderly patients who needed help with oral hygiene had 6.7 carious teeth or retained roots, nearly twice that of those who were self-sufficient. After adjusting for cognitive impairment and other factors, participants who needed help or supervision on oral hygiene had 1.7 times greater risk of having a carious tooth or retained root than those who were self sufficient. This evidence confirms that dental caries are highly associated with functional impairment. It also suggests that for those who lost their ability to sufficiently maintain oral hygiene, individualized oral hygiene care plans and caregiver training programs corresponding to the patient's functional capacity and level of support should be developed to improve oral hygiene. Additionally, an effective prevention care plan including a shorter dental recall interval, use of fluoride, and management of xerostomia should also be considered to prevent dental caries for these high-risk patients.

The present study was based on existing data that was originally collected for patient care purpose. The overall quality of these data might be questionable. However, the study clinic was a university-affiliated training clinic. A standard protocol had been established to ensure quality of care. As a part of routine care, patient's medical history was routinely verified by dental providers during comprehensive new patient assessments. Telephone calls to patients' physicians or nurse practitioners were typically initiated if questions or concerns arose during this process. Additionally, all clinical assessments including medical history, dental charting and radiographs and treatment plans were required to be reviewed and approved by one of two geriatric faculties who had substantial experience in caring for geriatric patients with special needs. This standard protocol applied to all the patients who received dental care in this clinic. Since all the information required for treatment planning needed to be readily available prior to review, this protocol also reduced chances of missing data and improved the data quality. For these reasons, we were able to include the records of all 600 community-dwelling patients in the analysis.

However, given that multiple dental providers were involved in patient care during the study period and that no interexaminer calibration was possible, the lack of a uniform criterion in caries assessment was one of the major limitations in this study. To address the potential variations in recording the existing dental conditions, we carefully reviewed the records of comprehensive oral exams and verified the caries lesions with radiographs of the patients during data collection. Dental caries and retained roots were then grouped together using one variable, number of carious teeth or retained roots. While this approach was helpful to minimize the potential variations in recording caries and associated conditions, it did not address the issue of misdiagnoses resulting from the lack of uniform criterion in caries detection. In general, due to lack of cooperation, caries assessment is usually more difficult and less accurate in patients with cognitive impairment than those without cognitive impairment. If this assumption held true here, the caries severity in the study participants with cognitive impairment could be under-estimated.

Another major limitation of this study was associated with the exposures of interest, cognitive impairment and capacity to perform oral hygiene. Cognitive and oral self-care functional assessments were abstracted from dental records; therefore, the reliability and accuracy of this data were questionable. To evaluate the quality of cognitive assessment, we conducted two validation studies. First, we evaluated the quality of these assessments using the data of nursing home (NH) residents with dementia who received care in the study clinic. NH residents were selected because the diagnoses of dementia of these patients were established by their physicians, geriatricians and neurologists and were fairly reliable. This internal validation found that the dentists in the study clinic were able to identify 97% of the NH patients with a diagnosis of dementia, indicating an acceptable reliability of this assessment. In addition, we also compared these assessments with existing literature. Based on the dental records, 75% of the NH participants were considered cognitively impaired. This finding was comparable to the results of the 2011 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures report, which indicated 70% of Minnesota NH residents have cognitive impairment43. This evidence shows that the cognitive assessments available in the existing dental records were fairly reliable.

Assessment of oral self-care function was also not based on a standardized instrument. Currently, there is no instrument available to assess dentally-related function in older adults with cognitive impairment. Although multiple instruments44-51 are widely used in geriatric practice for cognitive or functional assessment, they are not designed to be used in a dental environment. Due to the lack of a suitable instrument, self- or proxy-reported functional assessment, together with clinical assessment on cognitive status, physical function, level of cooperation to care and oral/denture hygiene status, are used collectively in clinical practice, including the study clinic, to evaluate oral self-care ability in cognitively-impaired patients. Although these assessments were not based on standardized instruments, given that oral/denture hygiene status was factored into the assessment, we are confident that the approach used to assess the capacity to perform oral hygiene care was acceptable. However, since there was no uniform standard used during the assessment, variation might present between examiners, which was one of the major limitations of this study.

Conclusion

The present study shows that while cognitive impairment and capacity to perform oral hygiene were both associated with the number of carious teeth or retained roots, cognitive impairment became insignificant when oral care capacity was adjusted for, indicating capacity to perform oral hygiene care mediate the association between cognitive impairment and dental caries severity among cognitively-impaired patients.

Contributor Information

Xi Chen, Department of Dental Ecology, School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Jennifer JJ Clark, Department of Biostatistics, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Hong Chen, Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Supawadee Naorungroj, Department of Epidemiology, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

References

- 1.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi S, Morley JE. Cognitive impairment. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:769–787. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muliyala KP, Varghese M. The complex relationship between depression and dementia. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2010;13(Suppl 2):69–73. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.74248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strachan MW, Reynolds RM, Marioni RE, et al. Cognitive function, dementia and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:108–114. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp SI, Aarsland D, Day S, et al. Alzheimer's Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group. Hypertension is a potential risk factor for vascular dementia: systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:661–669. doi: 10.1002/gps.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) 4th. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabert MH, Albert SM, Borukhova-Milov L, et al. Functional deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment: prediction of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:758–764. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert SM, Glied S, Andrews H, et al. Primary care expenditures before the onset of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2002;59:573–578. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst RL, Hay JW. Economic research on Alzheimer disease: a review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 6):135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moritz DJ, Kasl SV, Berkman LF. Cognitive functioning and the incidence of limitations in activities of daily living in an elderly community sample. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:41–49. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill TM, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME. Evaluating the risk of dependence in activities of daily living among community-living older adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:235–241. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.5.m235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agüero-Torres H, Thomas VS, Winblad B, et al. The impact of somatic and cognitive disorders on the functional status of the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10threvision (ICD-10): Chapter V, categories F00-F99, mental, behavioral and developmental disorders: clinical description and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. pp. 1–263. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeBettignies BH, Mahurin RK, Pirozzolo FJ. Insightfor impairment in independent living skills in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia. J Clink Exp Neuropsychol. 1990;12:355–363. doi: 10.1080/01688639008400980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunkin JJ, Anderson-Hanley C. Dementia caregiver burden: a review of the literature and guidelines for assessment and intervention. Neurology. 1998;51(Suppl 1):53–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1_suppl_1.s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farcnik K, Persyko MS. Assessment, measures and approaches to easing caregiver burden in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:203–215. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, et al. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47:191–198. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie J, Brayne C, Matthews FE, et al. Survival times in people with dementia: analysis from population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ. 2008;336:258–262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39433.616678.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu B, Plassman BL, Crout RJ, et al. Oral health disparities among elders with and without cognitive impairment. J Dent Res. 89(Special Issue A) Paper 129572. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu B, Plassman BL, Crout RJ, et al. Cognitive function and oral health among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:495–500. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ. Oral diseases and conditions in community-living older adults with and without dementia. Spec Care Dentist. 2003;23:7–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellefsen B, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. Caries prevalence in older persons with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:59–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ. Caries incidence and increments in community-living older adults with and without dementia. Gerodontology. 2002;19:80–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2002.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellefsen B, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. Assessing caries increments in elderly patients with and without dementia: a one-year follow-up study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1392–1400. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osterberg T, Mellström D, Sundh V. Dental health and functional ageing. A study of 70-year-old people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avlund K, Holm-Pedersen P, Schroll M. Functional ability and oral health among older people: a longitudinal study from age 75 to 80. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:954–962. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avlund K, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. Tooth loss and caries prevalence in very old Swedish people: the relationship to cognitive function and functional ability. Gerodontology. 2004;21:17–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1741-2358.2003.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart R, Sabbah W, Tsakos G, et al. Oral health and cognitive function in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Psychosom Med. 2008;70:936–941. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181870aec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Clark JJ. Assessment of Dentally-related Functional Competency for Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment – A Survey for Special-care Dental Professionals. doi: 10.1111/scd.12005. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score-matching methods for non-experimental causal studies. Rev Econom Statist. 2002;84:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenbaum PaulR. Observational Studies. New York: Springer Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:1481–1486. doi: 10.1177/0091270006292126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitts PM. The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. J Exp Psychol. 1954;47:381–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyle PA, Malloy PF, Salloway S, et al. Executive dysfunction and apathy predict functional impairment in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyle PA, Paul R, Moser D, et al. Cognitive and neurologic predictors of functional impairment in vascular dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jefferson AL, Paul RH, Ozonoff A, Cohen RA. Evaluating elements of executive functioning as predictors of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zadikoff C, Lang AE. Apraxia in movement disorders. Brain. 2005;128:1480–1497. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alzheimer's association. [Accessed on 5/4/2011];2011 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures report. http://www.alz.org/downloads/Facts_Figures_2011.pdf.

- 44.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh RP. ‘Mini-Mental state'. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jurica PJ, Leitten CL, Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale-2: Professional manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borson S. The mini-cog: a cognitive “vitals signs” measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:1021–1027. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::aid-gps234>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burns T, Mortimer JA, Merchak P. Cognitive Performance Test: a new approach to functional assessment in Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1994;7:46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katz S, Down TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in the development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]