Abstract

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) is a widely used model to study the initiation and progression of multiple sclerosis. Many researchers have used this model to investigate how the immune system and genetic factors contribute to the disease process. Current research has highlighted the importance of cytotoxic CD8 T cells and specific MHC class I alleles. Our lab has adopted this concept to create a novel mouse model to study the mechanism of blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, an integral feature of numerous neurological disorders. We have demonstrated that epitope-specific CD8 T cells cause disruption of the tight junction architecture and ensuing CNS vascular permeability in the absence of neutrophil support. This CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption is dependent on perforin expression. We have also elucidated a potential role for hematopoietic factors in this process. Despite having identical MHC class I molecules, similar inflammation in the CNS, and equivalent ability to utilize perforin, C57BL/6 mice are highly susceptible to this condition while 129 SvIm mice are resistant. This susceptibility is transferable with the bone marrow compartment. These findings led us to conduct a comprehensive genetic analysis which has revealed a list of candidate genes implicated in regulating traits associated with BBB disruption. Future studies will continue to define the underlying molecular mechanism of CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption and may assist in the development of potential therapeutic approaches to ameliorate pathology associated with BBB disruption in neurological disorders.

Keywords: Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), Blood-brain barrier (BBB), Peptide-induced fatal syndrome (PIFS), CNS vascular permeability, CD8 T cell

Introduction

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) is a small RNA picornavirus commonly used to study multiple sclerosis (MS), an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Intracerebral injection of the Daniel’s strain of TMEV produces a transient early meningoencephalitis in all mouse strains, while causing persistent infection of the white matter accompanied by demyelination in susceptible strains (Njenga et al, 1997; Rodriguez and David, 1985; Rodriguez et al, 1986). Since environmental agents such as viral infections have been associated with MS and infection with TMEV induces pathology similar to human MS, numerous researchers have adopted this model in an attempt to elucidate the mechanisms of disease initiation and progression and to develop potential therapeutic approaches to treat this disease (Denic et al, 2011). The TMEV model may also help us better understand the pathogenesis of additional diseases, such as those induced by Saffold virus, a human cardiovirus grouped with TMEV that may be involved in respiratory illnesses, GI illnesses, and type I diabetes in addition to neurological diseases (Himeda and Ohara, 2012).

TMEV as a model system to study CD8 T cells in MS

It has been shown that CD8 T cells are the predominant lymphocyte present in active MS lesions (Babbe et al, 2000). Therefore, many researchers have employed the TMEV model to investigate how CD8 T cells contribute to pathology associated with MS. One proposed mechanism of action is that TMEV induces autoreactive cytotoxic CD8 T cells resulting in CNS pathology including spinal cord lesions (Tsunoda et al, 2002; Tsunoda et al, 2005). Other studies have focused on the role of specific major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I alleles, which present peptide antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), in the pathogenesis of disease. Resistant C57BL/6 mice have been shown to clear viral infection by mounting a virus-specific CTL response that is highly focused on an immunodominant TMEV peptide, VP2121-130, presented in the context of the Db class I molecule (Johnson et al, 1999; Johnson et al, 2001). Interestingly, SJL/J mice, which are highly susceptible to TMEV infection, have also been shown to mount a fully functional virus-specific CTL response, producing IFN-γ and exhibiting the capability to lyse target cells. However, this response is largely restricted by the H-2Ks molecule and is ineffective at clearing virus infection (Kang et al, 2002). Furthermore, an analysis of (C57BL/6 x SJL/J) F1 progeny demonstrated that these mice showed a preference for an H-2Db-restricted CD8 T cell response and acquired resistance to TMEV infection (Jin et al, 2011) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Response of specific mouse strains to TMEV infection and induction of PIFS

| Strain | Persistent TMEV infection | CD8 T cell restriction | Major epitope(s) | Susceptibility to PIFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | No | H2-Db | VP2121-130 | Yes |

| SJL/J | Yes | H2-Ks | VP3159-166, VP111-20, VP3173-181 | Unknown |

| (C57BL/6 x SJL/J) F1 | No | H2-Db | VP2121-130 | Unknown |

| IFN-γR−/− | Yes | H2-Db | VP2121-130 | Yes |

| Perforin−/− | No | H2-Db | VP2121-130 | No |

| 129 SvIm | No | H2-Db | VP2121-130 | No |

Characterization of mouse strains according to whether they develop persistent TMEV infection, their CD8 T cell-restricted responses to specific major epitope(s), and their susceptibility to our PIFS model of CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption.

To further understand the role of epitope-specific CD8 T cells in contributing to neurological deficits associated with MS, another study inhibited Db:VP2121-130 epitope-specific CD8 T cells from susceptible IFN-γR−/− mice following TMEV infection. IFN-γR−/− mice mount strong Db:VP2121-130 epitope-specific CD8 T cell responses, but unlike C57BL/6 mice, are highly susceptible to TMEV infection (Table 1). Elimination of epitope-specific CD8 T cells from these mice resulted in preserved functional motor ability despite a slight trend towards a higher viral load (Johnson et al, 2001). Another recent study analyzed the role of epitope-specific CD8 T cells in promoting T1 black hole formation, which is visible as hypointense lesions on T1-weighted MRI scans. T1 black holes are a feature of human MS that is also observed in the TMEV model. Transfer of CD8 T cells into RAG1−/− mice resulted in average T1 black hole volume. However, depletion of epitope-specific CD8 T cells resulted in reduced T1 hypointensities, further supporting a role for epitope-specific CD8 T cells in the formation of T1 black holes and thus in pathology associated with human MS (Pirko et al, 2012). In summary, virus-specific CD8 T cells serve a dual purpose in that they can provide protection from TMEV-induced demyelinating diseases or directly contribute to neuropathogenesis.

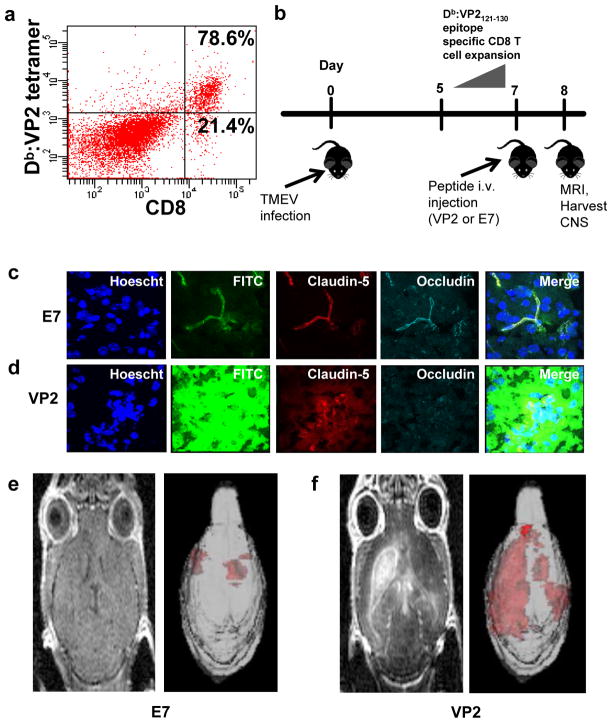

The Peptide-induced fatal syndrome (PIFS) model of CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption

In addition to playing a role in demyelinating diseases, CD8 T cells have also been implicated in disruption of the BBB. Our laboratory has employed a variation of TMEV infection to develop a novel mouse model of CNS vascular permeability, which is characteristic of numerous neurologic disorders, including dengue hemorrhagic fever, cerebral malaria, stroke, and acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (AHLE) in addition to MS (Brown et al, 1999; Huber et al, 2001; Lacerda-Queiroz et al, 2012; Medana and Turner, 2006; Minagar and Alexander, 2003; Nacer et al, 2012; Pirko et al, 2008; Talavera et al, 2004). As described in the previous section, C57BL/6 mice respond to intracranial TMEV infection by mounting an antiviral CD8 T cell response that is highly focused on an immunodominant TMEV peptide, VP2121-130, presented in the context of the Db class I molecule (Johnson et al, 1999; Johnson et al, 2001) (Figure 1a). Intravenous injection of VP2121-130 peptide seven days post-TMEV infection, during the peak of Db:VP2121-130 epitope-specific CD8 T cell expansion, results in severe CNS vascular permeability followed by death within 48 hours (Figure 1b). We have determined that this death is antigen-specific because TMEV-infected animals treated with mock E7 peptide remained asymptomatic (Johnson et al, 2005; Pirko et al, 2008). This difference is illustrated by confocal microscopic images, which show that VP2121-130-treated C57BL/6 mice exhibit degradation of the tight junction proteins claudin-5 and occludin in areas of FITC-albumin leakage compared to the preserved vascular integrity and intact tight junctions observed in E7-treated C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1c–1d). The extensive CNS vascular permeability in C57BL/6 mice treated with VP2121-130 peptide is also illustrated by 3D gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI scans (Figure 1e–1f). We have therefore termed this condition peptide induced fatal syndrome (PIFS). This inducible model system of BBB disruption enables a kinetic analysis of early and late cellular and gene expression events, making it an ideal system to investigate CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption, a hallmark feature of numerous neurological conditions.

Fig. 1. The Peptide-induced fatal syndrome (PIFS) model of CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis illustrating that the majority of CD8 T cells are specific for the VP2121-130 peptide presented in the context of the Db class I molecule. (b) C57BL/6 mice are intracranially infected with TMEV on day 0. VP2121-130 peptide or mock E7 peptide are intravenously administered on day 7, during the peak of CD8 T cell expansion. MRI is performed on the following day and then the CNS is harvested for additional assays. (c) Confocal microscopic images illustrate that mice treated with mock E7 peptide have intact tight junction proteins and preserved vascular integrity. (d) However, treatment with VP2121-130 peptide results in disruption of the tight junction proteins claudin-5 and occludin in areas of FITC-albumin leakage, indicative of CNS vascular permeability. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI images illustrate the extent of CNS vascular permeability after (e) administration of mock E7 peptide and (f) administration of VP2121-130 peptide to induce PIFS. 3D transparency rendering of gadolinium-enhancing areas are shown next to raw gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted scans. (f) Treatment with VP2121-130 peptide results in extensive CNS vascular permeability when compared to (e) treatment with mock E7 peptide

Molecular mechanisms in PIFS

Previous work done in our laboratory has highlighted the importance of CD8 T cells, perforin, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the PIFS model (Johnson et al, 2005; Suidan et al, 2010; Suidan et al, 2012; Suidan et al, 2008). We have also demonstrated that other factors implicated in promoting BBB disruption, such as CD4 T cells, TNF-α, IFN-γ, LTβR, and IL-1, do not play a role in lethality in this model system (Johnson et al, 2005). Due to the inducible nature of the PIFS model, we have also been able to determine the sequence of events that occur in the development of PIFS. We have demonstrated that astrocyte activation, as measured by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression, and alterations of the tight junction proteins claudin-5 and occludin occur prior to peak levels of CNS vascular permeability and functional motor deficits. It was also found that expression of perforin is essential for these processes to occur, as mice deficient in perforin exhibited negligible astrocyte activation, normal tight junction protein expression, and an absence of CNS vascular permeability (Suidan et al, 2008).

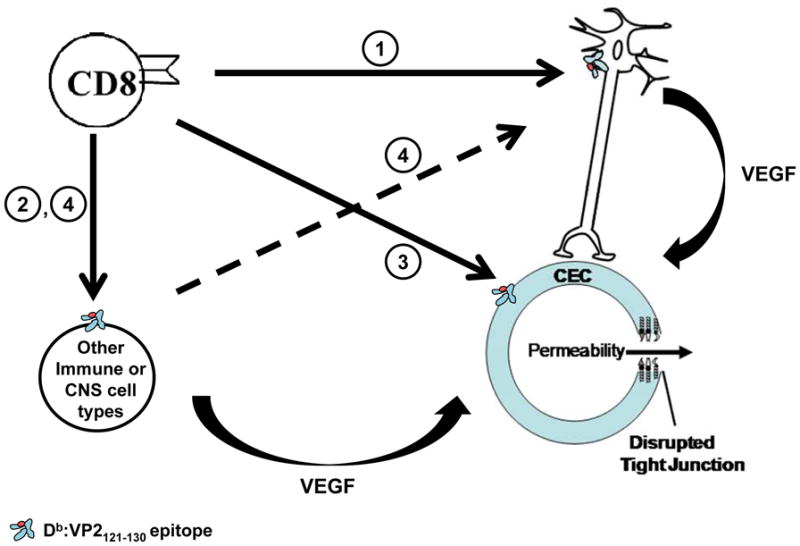

Dissecting the underlying molecular mechanisms of immune-mediated fatal BBB disruption is of critical importance for the development of therapeutic strategies to treat neurological disorders characterized by extensive BBB disruption. One potential mechanism is induction of VEGF in the CNS. Time-course experiments have enabled us to demonstrate that VEGF expression is significantly upregulated prior to and during peak levels of CNS vascular permeability. Inhibition of neuropilin-1, a VEGF coreceptor, resulted in a significant reduction in CNS vascular permeability, preservation of occludin protein levels, decreased microhemorrhage formation, and enhanced survival in C57BL/6 mice induced to undergo PIFS (Suidan et al, 2010; Suidan et al, 2012). Furthermore, in situ hybridization and confocal microscopy demonstrate that neurons are the major source of VEGF expression (Suidan et al, 2010). We have also shown that neurons are the primary cell type infected by TMEV and that CD8 T cells actively engage these TMEV-infected neurons (McDole et al, 2010). Together, these findings elucidate a potential mechanism of BBB disruption in which CD8 T cells interact with neurons to cause upregulation of VEGF, resulting in disruption of tight junction proteins and ensuing CNS vascular permeability (Figure 2, Pathway 1).

Fig. 2. Proposed mechanism of CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption based on summarized results acquired using the PIFS model system.

Our primary hypothesis is that (1) CD8 T cells engage neurons to cause upregulation of VEGF, promoting disruption of the tight junction architecture and ensuing CNS vascular permeability. Alternatively, it is possible that (2) CD8 T cells engage a different immune or CNS cell type, which may either cause upregulation of VEGF and directly lead to BBB disruption or (4) interact with neurons to increase VEGF, resulting in subsequent BBB disruption. It is also possible that (3) CD8 T cells directly engage cerebral endothelial cells to cause disruption of the tight junction proteins and ensuing CNS vascular permeability.

Evidence for other cell types involved in BBB disruption

It remains possible that other immune cell types in addition to CD8 T cells may also contribute to BBB disruption (Figure 2, Pathways 2 and 4). Previous studies have implicated neutrophils as being one such critical cell type, proposing that CD8 T cells attract this effector population to induce BBB disruption. This finding was demonstrated through the use of anti-GR-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) RB6-8C5 to deplete neutrophils in vivo (Kim et al, 2009). This method of neutrophil depletion has been widely used to investigate the role of neutrophils in several disease processes, including cancer, cerebral malaria, and viral-induced encephalitis (Breitbach et al, 2007; Chen et al, 2000; Kim et al, 2009; Tazawa et al, 2003; Zhou et al, 2003). However, this method has been shown to be nonspecific for neutrophils since RB6-8C5 binds to both Ly-6G on neutrophils and Ly-6C on lymphocytes and monocytes (Daley et al, 2008; Dunay et al, 2010). Using flow cytometric analysis, we demonstrated that CNS-infiltrating CD8 T cells are GR-1+. We also determined that treatment with anti-GR-1 mAb RB6-8C5 caused a significant reduction in CNS-infiltrating CD8 T cells in addition to GR-1+ cells when compared to treatment with anti-Ly6G mAb 1A8 or treatment with normal rat serum. We then investigated the effect of these depletion strategies on the tight junction architecture, CNS vascular permeability, and functional motor deficits in our PIFS model system. We discovered that specific depletion of neutrophils with anti-Ly6G mAb 1A8 still resulted in disruption of tight junction proteins occludin and claudin-5, severe CNS vascular permeability as revealed by 3D volumetric analysis of gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI images, and a significant decline in functional motor ability when compared to nonspecific depletion with anti-GR-1 mAb RB6-8C5 (Johnson et al, 2012a). While neutrophils have been shown to be associated with vascular leakage in other viral models, these findings using our system of CD8 T cell-initiated BBB disruption support a role for CD8 T cells to cause disruption of the tight junction architecture, severe CNS vascular permeability, and functional motor deficits in the absence of neutrophil support. Therefore, CD8 T cells remain a prime target for potential therapeutic strategies to treat disorders characterized by BBB disruption.

Role of hematopoietic factors in PIFS

In addition to immune cells, a role for hematopoietic factors in contributing to the mechanism of BBB disruption is also important to investigate since there is a relative lack of knowledge in this area. We have observed a difference in susceptibility to PIFS in C57BL/6 and 129 SvIm mouse strains despite these strains having identical MHC class I molecules, similar levels of VP2121-130 epitope-specific CNS-infiltrating CD8 T cells, and equivalent perforin-mediated killing. C57BL/6 mice displayed higher levels of astrocyte activation, severe CNS vascular permeability, increased microhemorrhage formation, and functional motor deficits compared to 129 SvIm mice. Therefore, we hypothesized that hematopoietic factors contribute to the characteristics associated with PIFS. In order to investigate this, we performed bone marrow transplants by reconstituting lethally irradiated 129 SvIm mice with either C57BL/6 bone marrow or autologous bone marrow. We discovered that 129 SvIm mice receiving C57BL/6 bone marrow now became susceptible to PIFS. This was illustrated by an increase in microhemorrhage formation, extensive CNS vascular permeability, and functional motor deficits when compared to 129 SvIm mice receiving autologous bone marrow transfer. Therefore, since susceptibility to PIFS is transferable with the bone marrow compartment, there is a potential role for hematopoietic factors in contributing to traits characteristic of immune-mediated fatal BBB disruption (Johnson et al, 2012b). It will be necessary to identify these hematopoietic factors to open up potential therapeutic interventions. Since the list of these potential factors is relatively extensive, our lab has recently performed a comprehensive genetic analysis of (C57BL/6 x 129 SvIm) F2 progeny, which we have observed to display variable susceptibility to PIFS. This analysis has allowed us to identify quantitative trait loci (QTL) on chromosomes 12 and 17 linked to functional motor deficit and CNS vascular permeability, respectively. These findings have resulted in a list of potential candidate genes implicated in regulating these traits, opening up future avenues of research to dissect the underlying molecular mechanisms of BBB disruption.

Conclusion

Our lab has used a variation of the TMEV model to develop a novel inducible model of CNS vascular permeability in order to elucidate the mechanism of BBB disruption in neurological diseases. Prior to the studies described above, there was a relative lack of knowledge regarding the extent inflammatory immune cells and hematopoietic factors contributed to BBB disruption. Research conducted in our lab has begun to shed light on these mechanisms. One potential mechanism is that CD8 T cells engage neurons, causing upregulation of VEGF and subsequent degradation of the tight junction architecture and CNS vascular permeability (Figure 2, Pathway 1). Alternatively, it is possible that CD8 T cells may engage another immune or CNS cell type, causing an increase in VEGF and leading to BBB disruption. This mechanism may be dependent or independent of engagement with neurons (Figure 2, Pathways 2 and 4). Furthermore, it is also possible that CD8 T cells directly engage cerebral endothelial cells to cause disruption of the tight junction proteins and ensuing CNS vascular permeability (Figure 2, Pathway 3). Future research will continue to define the mechanism of BBB disruption by analyzing the interaction of CD8 T cells with specific CNS cell types. We have chosen to focus on the CNS because we have previously shown through gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI scans that CD8 T cell-mediated vascular permeability is specific to the CNS and is not observed in peripheral organs (Suidan et al, 2010). Knowledge of the underlying mechanism of BBB disruption will be essential in the development of novel therapeutic approaches to ameliorate pathology associated with BBB disruption in neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health grant NS060881 and Mayo Graduate School.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Babbe H, Roers A, Waisman A, Lassmann H, Goebels N, Hohlfeld R, Friese M, Schroder R, Deckert M, Schmidt S, Ravid R, Rajewsky K. Clonal expansions of CD8(+) T cells dominate the T cell infiltrate in active multiple sclerosis lesions as shown by micromanipulation and single cell polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;192:393–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach CJ, Paterson JM, Lemay CG, Falls TJ, McGuire A, Parato KA, Stojdl DF, Daneshmand M, Speth K, Kirn D, McCart JA, Atkins H, Bell JC. Targeted inflammation during oncolytic virus therapy severely compromises tumor blood flow. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2007;15:1686–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H, Hien TT, Day N, Mai NT, Chuong LV, Chau TT, Loc PP, Phu NH, Bethell D, Farrar J, Gatter K, White N, Turner G. Evidence of blood-brain barrier dysfunction in human cerebral malaria. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 1999;25:331–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1999.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhang Z, Sendo F. Neutrophils play a critical role in the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2000;120:125–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denic A, Johnson AJ, Bieber AJ, Warrington AE, Rodriguez M, Pirko I. The relevance of animal models in multiple sclerosis research. Pathophysiology: the official journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology/ISP. 2011;18:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunay IR, Fuchs A, Sibley LD. Inflammatory monocytes but not neutrophils are necessary to control infection with Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Infection and Immunity. 2010;78:1564–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00472-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himeda T, Ohara Y. Saffold virus, a novel human Cardiovirus with unknown pathogenicity. Journal of virology. 2012;86:1292–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06087-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber JD, Egleton RD, Davis TP. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions in the blood-brain barrier. Trends in neurosciences. 2001;24:719–25. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YH, Kang HS, Mohindru M, Kim BS. Preferential induction of protective T cell responses to Theiler’s virus in resistant (C57BL/6 x SJL)F1 mice. Journal of virology. 2011;85:3033–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02400-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AJ, Mendez-Fernandez Y, Moyer AM, Sloma CR, Pirko I, Block MS, Rodriguez M, Pease LR. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells mediate a peptide-induced fatal syndrome. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:6854–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AJ, Njenga MK, Hansen MJ, Kuhns ST, Chen L, Rodriguez M, Pease LR. Prevalent class I-restricted T-cell response to the Theiler’s virus epitope Db:VP2121-130 in the absence of endogenous CD4 help, tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, perforin, or costimulation through CD28. Journal of virology. 1999;73:3702–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3702-3708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AJ, Upshaw J, Pavelko KD, Rodriguez M, Pease LR. Preservation of motor function by inhibition of CD8+ virus peptide-specific T cells in Theiler’s virus infection. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2001;15:2760–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0373fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HL, Chen Y, Jin F, Hanson LM, Gamez JD, Pirko I, Johnson AJ. CD8 T Cell-Initiated Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Is Independent of Neutrophil Support. Journal of immunology. 2012a;189:1937–1945. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HL, Chen Y, Suidan GL, McDole JR, Lohrey AK, Hanson LM, Jin F, Pirko I, Johnson AJ. A hematopoietic contribution to microhemorrhage formation during antiviral CD8 T cell-initiated blood-brain barrier disruption. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2012b;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang BS, Lyman MA, Kim BS. The majority of infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the central nervous system of susceptible SJL/J mice infected with Theiler’s virus are virus specific and fully functional. Journal of virology. 2002;76:6577–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6577-6585.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JV, Kang SS, Dustin ML, McGavern DB. Myelomonocytic cell recruitment causes fatal CNS vascular injury during acute viral meningitis. Nature. 2009;457:191–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda-Queiroz N, Rodrigues DH, Vilela MC, Rachid MA, Soriani FM, Sousa LP, Campos RDL, Quesniaux VFJ, Teixeira MM, Teixeira AL. Platelet-Activating Factor Receptor Is Essential for the Development of Experimental Cerebral Malaria. American Journal of Pathology. 2012;180:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDole JR, Danzer SC, Pun RY, Chen Y, Johnson HL, Pirko I, Johnson AJ. Rapid formation of extended processes and engagement of Theiler’s virus-infected neurons by CNS-infiltrating CD8 T cells. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:1823–33. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medana IM, Turner GD. Human cerebral malaria and the blood-brain barrier. International journal for parasitology. 2006;36:555–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagar A, Alexander JS. Blood-brain barrier disruption in multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis. 2003;9:540–9. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms965oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacer A, Movila A, Baer K, Mikolajczak SA, Kappe SH, Frevert U. Neuroimmunological blood brain barrier opening in experimental cerebral malaria. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002982. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njenga MK, Asakura K, Hunter SF, Wettstein P, Pease LR, Rodriguez M. The immune system preferentially clears Theiler’s virus from the gray matter of the central nervous system. Journal of virology. 1997;71:8592–601. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8592-8601.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirko I, Chen Y, Lohrey AK, McDole J, Gamez JD, Allen KS, Pavelko KD, Lindquist DM, Dunn RS, Macura SI, Johnson AJ. Contrasting roles for CD4 vs. CD8 T-cells in a murine model of virally induced “T1 black hole” formation. PloS one. 2012;7:e31459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirko I, Suidan GL, Rodriguez M, Johnson AJ. Acute hemorrhagic demyelination in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2008;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, David CS. Demyelination induced by Theiler’s virus: influence of the H-2 haplotype. Journal of immunology. 1985;135:2145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Pease LR, David CS. Immune-Mediated Injury of Virus-Infected Oligodendrocytes - a Model of Multiple-Sclerosis. Immunology Today. 1986;7:359–363. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(86)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suidan GL, Dickerson JW, Chen Y, McDole JR, Tripathi P, Pirko I, Seroogy KB, Johnson AJ. CD8 T cell-initiated vascular endothelial growth factor expression promotes central nervous system vascular permeability under neuroinflammatory conditions. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:1031–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suidan GL, Dickerson JW, Johnson HL, Chan TW, Pavelko KD, Pirko I, Seroogy KB, Johnson AJ. Preserved vascular integrity and enhanced survival following neuropilin-1 inhibition in a mouse model of CD8 T cell-initiated CNS vascular permeability. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2012;9:218. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suidan GL, McDole JR, Chen Y, Pirko I, Johnson AJ. Induction of blood brain barrier tight junction protein alterations by CD8 T cells. PloS one. 2008;3:e3037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera D, Castillo AM, Dominguez MC, Gutierrez AE, Meza I. IL8 release, tight junction and cytoskeleton dynamic reorganization conducive to permeability increase are induced by dengue virus infection of microvascular endothelial monolayers. The Journal of general virology. 2004;85:1801–13. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazawa H, Okada F, Kobayashi T, Tada M, Mori Y, Une Y, Sendo F, Kobayashi M, Hosokawa M. Infiltration of neutrophils is required for acquisition of metastatic phenotype of benign murine fibrosarcoma cells: implication of inflammation-associated carcinogenesis and tumor progression. The American journal of pathology. 2003;163:2221–32. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63580-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda I, Kuang LO, Fujinami RS. Induction of autoreactive CD8(+) cytotoxic T cells during Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection: Implications for autoimmunity. Journal of virology. 2002;76:12834–12844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12834-12844.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda I, Kuang LQ, Kobayashi-Warren M, Fujinami RS. Central nervous system pathology caused by autoreactive CD8(+) T-cell clones following virus infection. Journal of virology. 2005;79:14640–14646. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14640-14646.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Stohlman SA, Hinton DR, Marten NW. Neutrophils promote mononuclear cell infiltrationduring viral-induced encephalitis. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:3331–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]