Background: The V-ATPase is induced to assemble during TLR-activated maturation of dendritic cells.

Results: Cluster disruption of dendritic cells also induces V-ATPase assembly by a PI3K/mTOR-dependent mechanism.

Conclusion: Semi-mature dendritic cells show increased V-ATPase assembly.

Significance: Dendritic cell maturation associated with immune tolerance involves V-ATPase assembly.

Keywords: ATPases, Dendritic Cells, Proton Pumps, Transport, Vacuolar Acidification, Vacuolar ATPase, Regulated V-ATPase Assembly

Abstract

The vacuolar (H+)-ATPases (V-ATPases) are ATP-driven proton pumps composed of a peripheral V1 domain and a membrane-embedded V0 domain. Regulated assembly of V1 and V0 represents an important regulatory mechanism for controlling V-ATPase activity in vivo. Previous work has shown that V-ATPase assembly increases during maturation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells induced by activation of Toll-like receptors. This increased assembly is essential for antigen processing, which is dependent upon an acidic lysosomal pH. Cluster disruption of dendritic cells induces a semi-mature phenotype associated with immune tolerance. Thus, semi-mature dendritic cells are able to process and present self-peptides to suppress autoimmune responses. We have investigated V-ATPase assembly in bone marrow-derived, murine dendritic cells and observed an increase in assembly following cluster disruption. This increased assembly is not dependent upon new protein synthesis and is associated with an increase in concanamycin A-sensitive proton transport in FITC-loaded lysosomes. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with wortmannin or mTORC1 with rapamycin effectively inhibits the increased assembly observed upon cluster disruption. These results suggest that the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mTOR pathway is involved in controlling V-ATPase assembly during dendritic cell maturation.

Introduction

Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells that function in immune surveillance. Dendritic cells exist in three principal states (1). In peripheral tissues, they are present in an immature state characterized by a high rate of endocytosis that allows them to take up various self-antigens (2). Dendritic cells can be induced to mature by pathogens that stimulate via pattern recognition receptors known as Toll-like receptors (TLRs)3 (3–5). TLR-induced maturation is characterized by higher rates of endocytosis and antigen processing, up-regulation of chemokine receptors and co-stimulatory molecules, and secretion of inflammatory cytokines that activate other cells associated with an immune response, including macrophages and neutrophils (6, 7). Upon activation through TLRs, dendritic cells also migrate to the lymphoid organs, where they interact with T-cells. During maturation, endocytosed proteins are degraded within lysosomes to small peptides, which are then loaded onto MHC class II molecules. These MHCII-peptide complexes are then expressed on the surface of mature dendritic cells, where they stimulate T-cell proliferation and an immune response (1).

In the absence of TLR agonists, dendritic cells spontaneously achieve a semi-mature state associated with T-cell tolerance to self-antigens (8–10). Semi-mature (or tolerogenic) dendritic cells secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines that induce T-cells to become tolerant toward specific MHC-peptide complexes (11). Because semi-mature dendritic cells present only self-peptides, this pathway is important in preventing immune responses to self-antigens (12). Thus, a lack of tolerogenic dendritic cells can result in the development of autoimmune diseases. Multiple in vitro models exist to induce dendritic cells to enter a semi-mature, tolerogenic state (6, 11, 13). One of these, cluster disruption, induces maturation through activation of integrins and E-cadherins on the dendritic cell surface (11). A greater understanding of the cellular processes occurring upon activation of dendritic cells to assume a semi-mature state has potential implications for the prevention of autoimmune disorders.

An important feature of dendritic cell maturation required for efficient antigen processing is the acidification of the antigen processing compartment by the vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) (14). V-ATPases are a family of ATP-dependent proton pumps that are ubiquitously expressed and present in both intracellular compartments and on the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells (15–17). Acidification of intracellular compartments is necessary for many pH-dependent processes, including receptor-mediated endocytosis, intracellular trafficking, and protease activation (15). V-ATPases are composed of a peripheral domain (V1) that hydrolyzes ATP and an integral domain (V0) that translocates protons (18), and operate via a rotary mechanism (19, 20). An important mechanism of controlling V-ATPase activity in vivo is the regulated assembly of the V1 and V0 domains (21). This process has been most extensively studied in yeast, where disassembly occurs rapidly and reversibly upon glucose depletion and has been shown not to require new protein synthesis (22, 23). Regulated assembly of the V-ATPase has also been observed in higher eukaryotes. In insect cells, disassembly occurs during molting while in renal cells, like in yeast, V-ATPase assembly is also controlled by glucose concentrations (24, 25). EGF stimulation of hepatocytes has also been shown to increase V-ATPase assembly on the lysosomal membrane (26). V-ATPase assembly has been shown previously to occur in dendritic cells following activation and maturation in response to LPS, which is a TLR4 agonist (14). LPS treatment induces a reduction in lysosomal pH in dendritic cells from 5.4 to 4.5 and an increase in concanamycin A-sensitive, ATP-dependent proton transport in dendritic cell lysosomes (14, 27). Furthermore, fractionation experiments demonstrate an LPS-induced shift in localization of the V1 domain from the cytoplasm to the membrane, indicative of increased V-ATPase assembly (14). Due to increasing interest in tolerance-inducing dendritic cells for therapeutic applications, we examined whether cluster disruption leading to semi-mature dendritic cells also results in increased V-ATPase assembly. Furthermore, we wished to elucidate the signaling pathways that regulate V-ATPase assembly upon dendritic cell maturation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Antibodies

RPMI 1640 medium, FBS, HEPES, and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen. GM-CSF was purchased from R&D Systems. 70-μm mesh strainers were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. PMSF and FITC-dextran were purchased from Sigma. Pre-cast polyacrylamide mini-protean TGX gels, Tween 20, SDS, nitrocellulose membranes, 2-mercaptoethanol, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Bio-Rad and anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Abcam. The chemiluminescence substrate for horseradish peroxidase was purchased from General Electric, and the signal was detected using Kodak BioMax Light film. Mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize mouse V-ATPase A and d subunits were purchased from Abnova and Abcam, respectively. A mouse monoclonal antibody that recognizes α-tubulin was purchased from Genscript. A rabbit monoclonal antibody that recognizes phospho-Akt was purchased from Cell Signaling. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma.

Dendritic Cell Isolation

Dendritic cell culture protocol was adapted from Inaba et al. (28). Bone marrow cells were obtained from 6–8-week-old female C3H/HeJ and BALB/c mice from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. Femurs and tibiae were dissected and stored in cold RPMI 1640 medium. Blunt forceps were used to clean bones of muscle, and scissors were used to remove the ends of each bone. Using a 25-gauge needle attached to a syringe filled with RPMI 1640, bone marrow cells were flushed from each bone into a sterile Petri dish. The bone marrow cell suspension was cleared of debris by transferring through a 70-μm mesh strainer. Cells were collected by centrifuging at 500 × g, and red blood cells were lysed by incubating the cells for 3 min at room temperature in an ammonium chloride solution (20 mm Tris, 140 mm NH4Cl, pH 7.2). Cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640, resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/ml in growth medium (RPMI 1640 with 5% FBS, 10 mm HEPES, 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) supplemented with 5 ng/ml GM-CSF, and plated onto 24 well plates at 1 ml (1 × 106 cells) per well. Cells were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37 °C with 5% CO2. On days 2 and 4, cells were fed by aspirating the medium, washing once with RPMI 1640, and adding fresh growth medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml GM-CSF.

Dendritic Cell Maturation

Cells that were induced to mature were harvested on day 6 with gentle pipetting, collected by centrifugation, resuspended at <1 × 106 cells/ml in growth medium containing either 100 ng/ml LPS (Escherichia coli type 0111:B4) for LPS-treated cells, or in the absence of maturing agents, for cluster-disrupted cells. For immature dendritic cells, cells were maintained after day 6 in culture medium without replating or LPS addition. Rapamycin and wortmannin-treated cells were preincubated for 1 h with 10 ng/ml rapamcyin or 100 nm wortmannin prior to harvesting. Cells were maintained in rapamycin or wortmannin for the indicated incubation times.

Cell Fractionation and Western Blot Analysis

Day 7 bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were harvested with gentle pipetting or scraping of cells and immediately placed on ice. Cells were washed twice with cold Hanks-buffered saline solution and resuspended in 0.5 ml of homogenization buffer (250 mm sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm HEPES, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mm PMSF, pH 7.2). Cells were homogenized by passing 20 times through a ball-bearing homogenizer fitted with a ball allowing 12 μm of clearance. The lysate was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and then the post-nuclear supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to obtain the membrane and cytosolic fractions (14). The membrane pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer, and the cytosolic fraction was concentrated using an Amicon Ultra filter with a 10-kDa cut-off. Protein concentration was determined using a Lowry assay (29), and 10 μg of protein from each fraction was separated by SDS-PAGE (30). After transferring proteins to nitrocellulose, Western blotting was performed using an anti-A subunit antibody. A mouse anti-d subunit antibody and an α-tubulin antibody were used to confirm the purity of the fractions and as loading controls for the membrane and cytosolic fractions, respectively. Primary antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and chemiluminescent detection reagents. Western blots were quantitated using ImageJ software. The ratio of A subunit in the membrane fraction versus the cytosolic fraction was calculated as a measure of V-ATPase assembly. To normalize the results between independent experiments, the ratio for each experimental condition tested was divided by the ratio observed for the immature cells for that set of experiments. It should be noted that some variability was observed for the degree of assembly for immature dendritic cells between independent experiments, possibly due to a low but variable degree of maturation for different batches of cells. The graphed data are averages (± S.E.) from the indicated number of independent experiments. Significance was calculated using a student's t test.

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting

Cells were suspended at 2 × 107 cells/ml in staining buffer (phenol-free HBSS with 1% BSA, 0.1% sodium azide), and 1 × 106 cells were incubated on ice for 20 min with 2.5 μg/ml APC-CD11c and FITC-CD86. Cells were washed twice with the following buffer (PBS with 1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide), resuspended in 500 μl of the same buffer, and stored on ice until sorting. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed using the Tufts Core Facility BD FACSCalibur cell sorter.

FITC-dextran Loading and Concanamycin A-sensitive Proton Transport

On day 6 of dendritic cell culture, lysosomes were loaded with FITC-dextran by incubating cells in warm culture medium supplemented with 2 mg/ml FITC-dextran for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed three times with warm culture medium and chased with warm culture medium for 30 min at 37 °C to allow transfer of FITC-dextran to lysosomes (14). Cells were either harvested by pipetting for cluster disruption or left unstimulated. After a 19-h incubation, cells were harvested and fractionated as described above. The membrane fractions were resuspended in assay buffer (125 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, with KOH) and incubated for 1 h on ice, whereas protein measurements were performed by the Lowry assay (29). Assay buffer (0.5 ml) was prewarmed to 37 °C, and 20 μg of membrane protein was added together with 1 μm concanamycin A or an equivalent volume of dimethyl sulfoxide. Fluorescence was recorded with excitation at 490 nm and emission at 520 nm. The initial slope of fluorescence quenching was measured after the addition of 1 mm Mg-ATP.

RESULTS

Comparison of Increased V-ATPase Assembly upon TLR-induced Maturation of Dendritic Cells Isolated from BALB/c and C3H/HeJ Mice

Trombetta et al. (14) demonstrated that induction of dendritic cell maturation by LPS results in increased V-ATPase assembly, decreased lysosmal pH, increased V-ATPase-dependent lysosomal acidification, and increased antigen processing. This study was carried out using dendritic cells isolated from C3H/HeJ mice, which lack a functional TLR4 receptor (31).4 Because TLR4 is the receptor for LPS, these cells are unable to respond to pure LPS but can be induced to mature by commercial LPS, which contains lipoprotein contaminants that stimulate maturation through TLR2 (32). This strain was employed in the original study to minimize maturation induced by low levels of contaminating LPS in glassware and medium.4

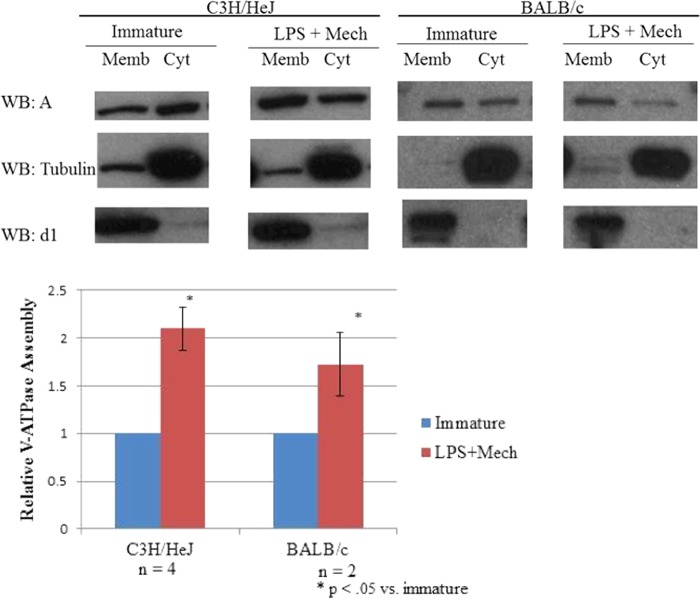

We first wished to demonstrate that increased V-ATPase assembly upon maturation was not restricted to dendritic cells isolated from C3H/HeJ mice. Mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were generated by incubating progenitor cells from both C3H/HeJ mice and BALB/c mice in the presence of GM-CSF for 7 days. For cells induced to mature, on day 6 of culture, loosely adherent, immature dendritic cells were harvested with gentle pipetting and plated at low density in growth medium containing 100 ng/ml commercial grade LPS (as in the original study) (14). Control cells, which remained immature, did not undergo replating and were not treated with LPS on day 6. After a 19-h incubation, the LPS-treated cells were visibly mature; they were adherent and had spread on the tissue culture plate with long extended processes. The immature control cells remained small and rounded in morphology (1). Immature and LPS-treated cells were then both harvested for fractionation. The harvested cells were homogenized and fractionated by high speed centrifugation to separate the membrane and the cytosolic fractions (14). Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting using an antibody against subunit A (part of the V1 domain) was performed on both membrane and cytosolic fractions to assess V-ATPase assembly. Increased assembly appears as a shift in subunit A from the cytosolic to the membrane fraction. An antibody against subunit d (part of the V0 domain) was used as a loading control for the membrane fraction and an antibody against α-tubulin was used as a loading control for the cytosolic fraction. We observed a shift in the amount of V1 domain from the cytosolic to the membrane fraction (reflecting greater assembly) upon LPS-induced maturation of dendritic cells isolated from both C3H-HeJ and BALB-c mice (Fig. 1). This result indicates that increased V-ATPase assembly upon dendritic cell maturation is not restricted to the C3H-HeJ line.

FIGURE 1.

LPS treatment of dendritic cells isolated from BALB/C and C3H/HeJ mice induces increased V-ATPase assembly. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ and BALB/c mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the presence of 100 ng/ml LPS. Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium without replating. After 19 h, cells were harvested, cytosolic (Cyt) and membrane (Memb) fractions were prepared, and aliquots were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (WB) using antibodies against subunit A (part of the V1 domain), subunit d (part of the V0 domain), and α-tubulin. Increased assembly of the V-ATPase is reflected by an increase in the amount of subunit A present in the membrane fraction versus the cytosolic fraction. Western blots shown are representative images of the results obtained from multiple independent experiments. The degree of V-ATPase assembly was quantified as described under “Experimental Procedures,” with the mean degree of assembly for each condition expressed relative to that observed for immature cells. The number of independent experiments is indicated by n, and error bars represent S.E. Mech, mechanical stimulation.

Cluster Disruption of Dendritic Cells Induces Increased V-ATPase Assembly

Based upon the absence of functional TLR4 receptors on dendritic cells isolated from C3H/HeJ mice, we predicted that treatment of these cells with Pam3Cys (a TLR2-specific agonist) but not ultrapure LPS (which lacks lipoprotein contaminants) would induce increased V-ATPase assembly (5, 32, 33). Surprisingly, both TLR agonists induced an increase in V-ATPase assembly (data not shown).

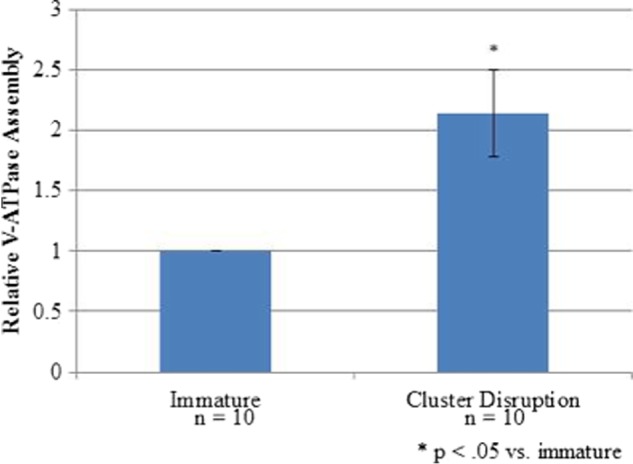

This prompted us to examine whether the harvesting protocol employed was sufficient to induce V-ATPase assembly. The mechanical stimulation associated with harvesting has been shown to cause “cluster disruption” of dendritic cells (6, 13, 34). Cluster disruption induces a semi-mature state of dendritic cells associated with immune tolerance (see below) (34). To test whether cluster disruption was capable of inducing increased V-ATPase assembly, immature dendritic cells were harvested and replated followed by incubation for 19 h in the absence of TLR agonists. Control cells were again maintained in an immature state by not harvesting until after this 19-h incubation period. As shown in Fig. 2, harvesting followed by the 19-h incubation period also led to increased V-ATPase assembly. Thus, the semi-mature state of dendritic cells induced by cluster disruption is also associated with increased V-ATPase assembly.

FIGURE 2.

Cluster disruption is sufficient to induce V-ATPase assembly. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist (cluster disruption). Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium without replating. After 19 h, cells were harvested, and cytosolic and membrane fractions were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Relative assembly was quantified as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

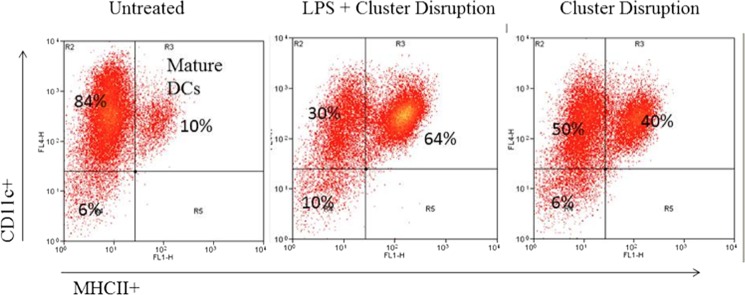

Cluster Disruption of Dendritic Cells Induces a Semi-mature Phenotype

A key feature of the semi-mature state of dendritic cells induced by cluster disruption is that, as with the fully mature state induced by TLR stimulation, they are MHCII-positive, indicating that they are capable of presenting peptides on their cell surface (8). To confirm that the cells isolated and employed in the present study are indeed semi-mature dendritic cells, fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed on immature dendritic cells, dendritic cells induced to mature with both LPS and cluster disruption, and dendritic cells induced to mature with cluster disruption alone. Technical issues with the harvesting protocol prevented us from characterizing dendritic cells induced to mature by treatment with LPS in the absence of cluster disruption. Cells were analyzed for both a dendritic cell marker (CD11c) and a maturation marker (MHCII). As shown in Fig. 3, 90–94% of the cell populations analyzed were CD11c-positive, indicating very pure populations of dendritic cells. Contaminating macrophages and granulocytes likely account for the CD11c-negative cell population (28). Moreover, cluster disruption resulted in ∼40% of the cells being MHCII-positive compared with 64% for cluster disruption plus LPS and 10% for immature cells, indicating that cluster disruption resulted in a substantial fraction of cells exhibiting this maturation marker.

FIGURE 3.

Cluster disruption of dendritic cells induces the appearance of the maturation marker MHCII. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist (cluster disruption) or in the presence of 100 ng/ml LPS (LPS + cluster disruption). Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium without replating (Untreated). After 19 h, cells were harvested and analyzed for the dendritic cell (DC)-specific marker (CD11c) and the maturation marker (MHCII) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

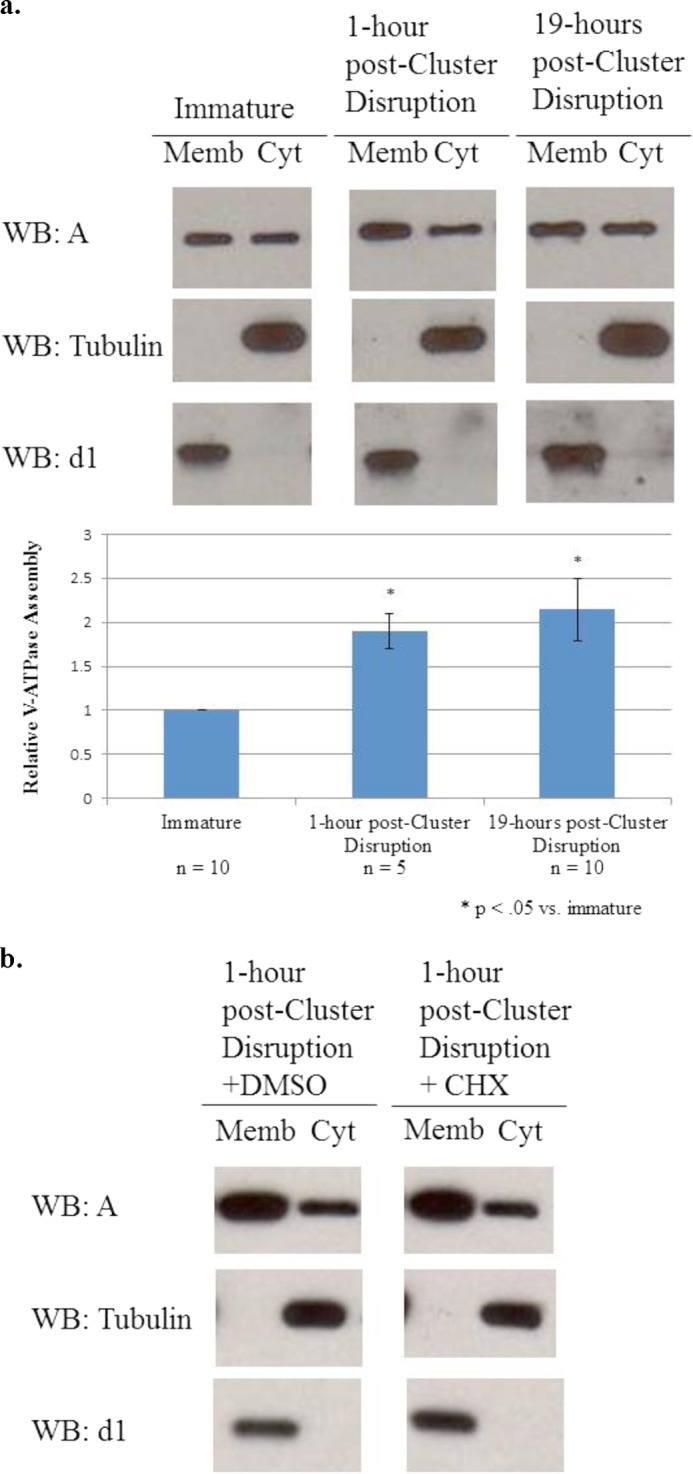

V-ATPase Assembly Begins within 1 h after Cluster Disruption and Requires No New Protein Synthesis

Because of both the clinical relevance of tolerogenic dendritic cells and the technical difficulty of separating the effects of TLR activation from cluster disruption on V-ATPase assembly, we chose to pursue investigation of the signaling pathways regulating V-ATPase assembly using cluster disruption alone. Dendritic cells from C3H/HeJ mice continued to be employed to ensure that maturation was not induced by TLR4 activation by contaminating LPS (31). To determine how rapidly V-ATPase assembly occurs following cluster disruption, assembly at 1 and 19 h following cluster disruption was compared with that observed for immature cells. As shown in Fig. 4, increased V-ATPase assembly is already observed at 1 h post stimulation and remains elevated at 19 h post stimulation. This result suggests that, as in other systems in which V-ATPase assembly is regulated temporally, regulation likely occurs at a post-translational level (22). To test whether new protein synthesis is required for increased V-ATPase assembly, cells were preincubated for 30 min with 1 ng/ml cycloheximide prior to cluster disruption and for 1 h following disruption prior to harvesting. Cycloheximide-treated dendritic cells displayed the same increase in assembly following cluster disruption as untreated cells (Fig. 4b).

FIGURE 4.

V-ATPase assembly increases rapidly after cluster disruption and does not require new protein synthesis. a, day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist (cluster disruption). Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium without replating. Cells were harvested 1 or 19 h after stimulation by cluster disruption. Cytosolic (Cyt) and membrane (Memb) fractions were prepared, and gel electrophoresis and Western blotting (WB) were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Western blots are representative images of the results obtained from five independent experiments. Relative assembly was quantified as described in the legend to Fig. 1. b, cells were treated for 30 min prior to cluster disruption with either 1 ng/ml cycloheximide (CHX) or the equivalent volume of vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide; DMSO) and then cluster disrupted and maintained in the same conditions for 1 h prior to cell fractionation and analysis of V-ATPase assembly as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Images are representative of two independent experiments.

PI3K/mTOR Signaling Regulates Increased V-ATPase Assembly after Cluster Disruption-induced Maturation of Dendritic Cells

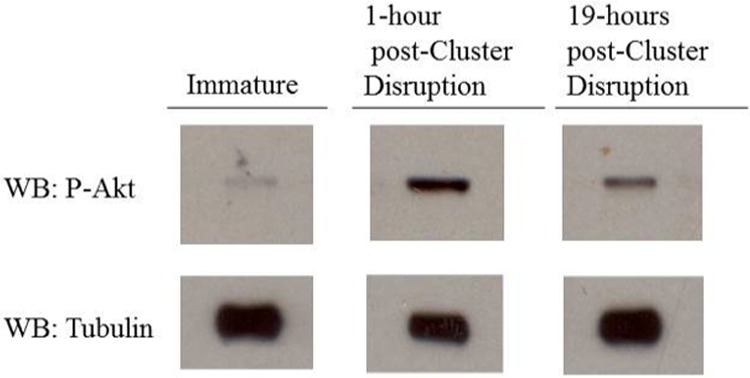

Cluster disruption has been shown to induce dendritic cell maturation through activation of integrin/E-cadherin signaling (see below). Akt is a common downstream target of integrin activation and previous reports have demonstrated that Akt activation by phosphorylation occurs following integrin stimulation (35). To determine whether Akt is activated following cluster disruption of dendritic cells, the level of phospho-Akt was measured by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 5, increased phosphorylation of Akt was observed as early as 1 h following cluster disruption. Akt activation thus appears to parallel the observed increase in V-ATPase assembly following cluster disruption.

FIGURE 5.

Akt is activated within one hour after cluster disruption. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist (cluster disruption). Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium without re-plating. Cells were harvested one hour and 19 h after stimulation by cluster disruption, and cytosolic and membrane fractions were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting using an antibody against the phosphorylated, active form of Akt were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Western blots (WB) are representative images from two independent experiments.

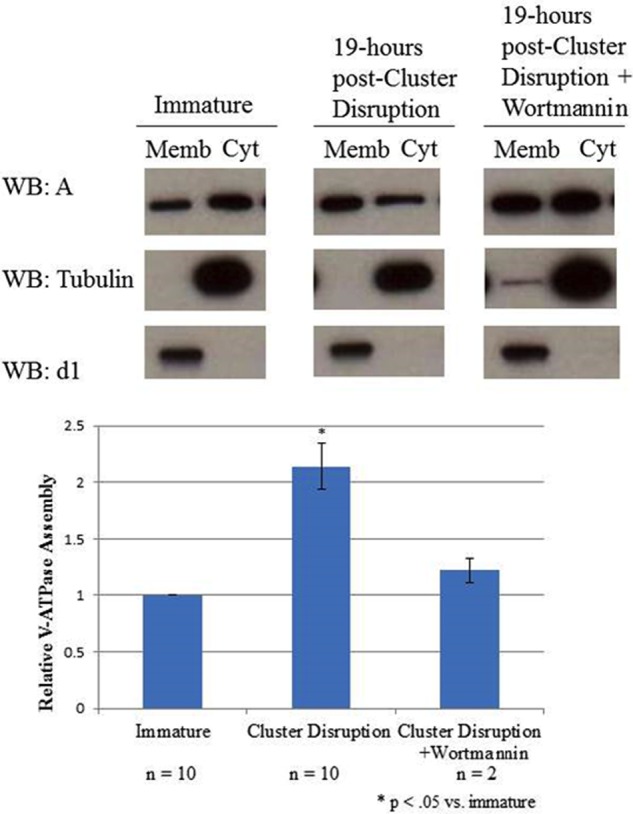

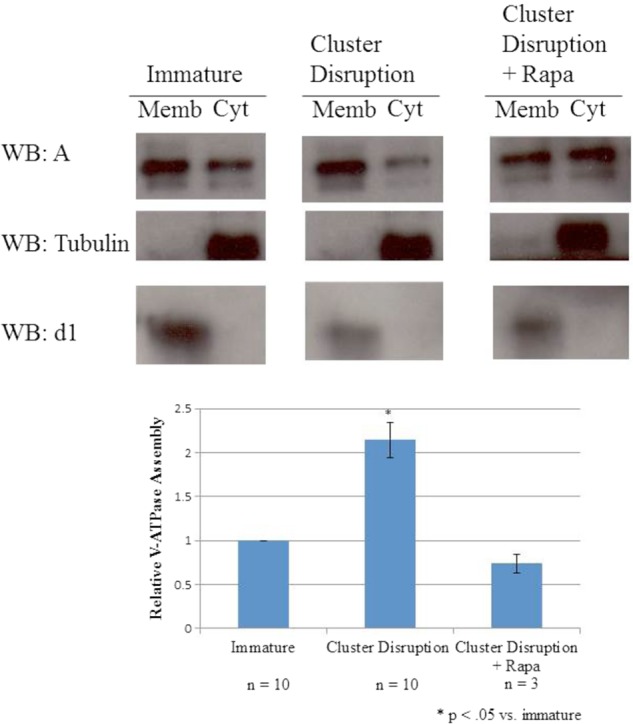

An important upstream regulator of Akt is PI 3-kinase, whereas a major downstream target of activated Akt is the mTOR complex (36, 37). To determine whether PI 3-kinase and mTOR are involved in increased assembly of the V-ATPase following cluster disruption of dendritic cells, the effect of the PI 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin and the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin on this process was determined. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of inhibitors for 1 h prior to cluster disruption and for the 19-h incubation following replating. As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, both wortmannin and rapamycin effectively blocked the cluster disruption-induced increase in V-ATPase assembly. These results suggest that the PI 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade is involved in increased V-ATPase assembly following cluster disruption of dendritic cells.

FIGURE 6.

The PI 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin blocks cluster disruption-induced V-ATPase assembly. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist (cluster disruption) in the presence or absence of 100 nm wortmannin. Wortmannin-treated cells were preincubated for one hour with 100 nm wortmannin prior to cluster disruption and remained in the presence of the inhibitor for the following incubation. Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium until harvesting without replating. After 19 h cells were harvested, and cytosolic (Cyt) and membrane (Memb) fractions were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting (WB) were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Western blots are representative images from two independent experiments. Relative assembly was quantified as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

FIGURE 7.

The mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin blocks cluster disruption-induced V-ATPase assembly. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist (cluster disruption) in the presence or absence of 10 ng/ml rapamycin (Rapa). Rapamycin-treated cells were preincubated for 1 h with inhibitor prior to cluster disruption and remained in the presence of the inhibitor for the following incubation. Immature dendritic cells were maintained in growth medium until harvesting without replating. After 19 h, cells were harvested, and cytosolic (Cyt) and membrane (Memb) fractions were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting (WB) were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Western blots are representative images from multiple independent experiments. Relative assembly was quantified as described in Fig. 1.

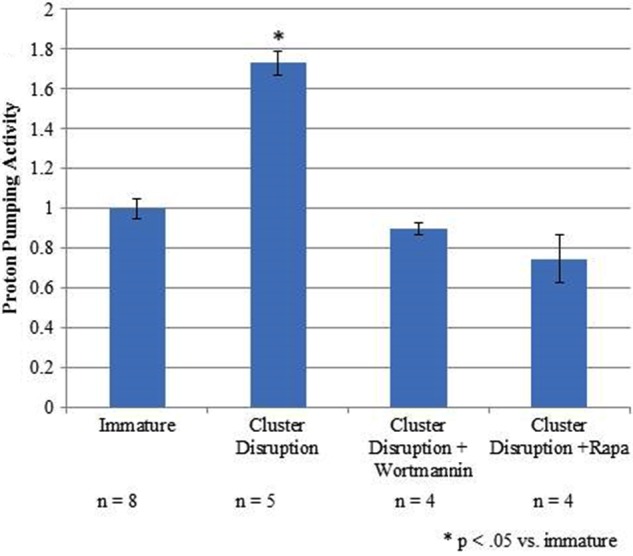

Increased V-ATPase Assembly Leads to Increased Proton Transport Activity

To determine whether the increased V-ATPase assembly observed upon cluster disruption resulted in functional complexes, ATP-dependent, concanamycin A-sensitive proton transport was measured in FITC-loaded lysosomes (27, 14). Immature dendritic cells on day 6 were incubated with FITC-dextran for 30 min at 37 °C followed by a 30-min chase to allow accumulation of the pH-sensitive dye in lysosomal compartments by endocytosis. Cells were either subjected to cluster disruption or were left unstimulated, and all cells were then subjected to a 19-h incubation. Cells were then homogenized, and lysosomal acidification was measured as the concanamycin A-sensitive fluorescence quenching observed upon addition of Mg-ATP. As shown in Fig. 8, cluster disruption results in a significant increase in V-ATPase-dependent lysosomal acidification. Treatment with the inhibitors rapamycin and wortmannin completely blocked the cluster disruption-induced increase in proton pumping activity. These results indicate that cluster disruption results in the assembly of functional V-ATPase complexes on lysosomal membranes.

FIGURE 8.

Increased V-ATPase assembly correlates with increased concanamycin A-sensitive proton-pumping activity. Day 6 dendritic cell cultures from C3H/HeJ mice were loaded with FITC-dextran for 30 min followed by a 30-min chase. Rapamycin (Rapa) and wortmannin-treated cells were preincubated for 1 h with 10 ng/ml rapamcyin or 100 nm wortmannin prior to harvesting and maintained in the presence of the inhibitor. Cluster disrupted cells were stimulated to mature by replating in the absence of any TLR agonist. Immature cells were maintained in growth medium without replating. After 19 h, cells were harvested, and a membrane fraction containing FITC-loaded lysosomes was prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Proton transport activity was assessed by measuring the initial rate of ATP-dependent, concanamycin A-sensitive fluorescence quenching. Error bars represent standard error. A Student's t test was performed (p < 0.05). Data were combined from six independent experiments with at least two samples per experiment.

DISCUSSION

Semi-mature, tolerogenic dendritic cells are less characterized than fully mature, immunogenic dendritic cells but have recently gained attention for their role in immune tolerance (12). Resident immature dendritic cells present in tissues spontaneously migrate to the lymphatic system. This steady state turnover occurs as quickly as 3–5 days in secondary lymphoid organs (8, 13, 38, 39). Although the signals triggering spontaneous maturation are not well understood, it is thought that disruption of cell/cell and cell/matrix contacts associated with migration leads to stimulation of integrin and E-cadherin signaling, leading to a semi-mature state (13, 11). Upon migration, semi-mature dendritic cells present self-peptides as well as an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile to T-cells, which tolerize T-cells to self-antigens. Stimulation of integrins and E-cadherins by cluster disruption of dendritic cells in vitro also leads to this semi-mature phenotype (13, 11, 14).

In this study, we have shown that increased V-ATPase assembly occurs upon cluster disruption of dendritic cells. This likely facilitates the processing of self-antigens required for immune tolerance. Furthermore, increased V-ATPase assembly occurs within 1 h after cluster disruption and requires no new protein synthesis. It is interesting to note that within the first hour after TLR activation of dendritic cells, a transient increase in endocytosis and antigen processing is observed (40). This is thought to facilitate the uptake and processing of additional immunogenic macromolecules. It is possible that a similar increase in antigen uptake and processing may occur upon cluster disruption of dendritic cells.

We hypothesize that if maturation of dendritic cells by both LPS and cluster disruption result in increased V-ATPase assembly, a common signaling pathway may be involved in regulating this process. PI 3-kinase and mTOR are activated by both integrins and TLR stimulation in dendritic cells. Inhibiting PI 3-kinase and mTOR blocks many of the LPS induced maturation phenotypes, although the effects on the properties of cluster disrupted dendritic cells have not previously been investigated (37, 12). We show here that treating dendritic cells with either wortmannin (to inhibit PI 3-kinase) or rapamycin (to inhibit mTOR) blocks V-ATPase assembly induced by cluster disruption. This may be significant in clinical settings if patients are being treated with tolerogenic-dendritic cells to induce immune tolerance and concurrently with rapamycin as an immunosuppressive reagent.

PI 3-kinase has been shown to regulate V-ATPase activity post-translationally in other systems. In the ruffled border of osteoclasts, inhibition of PI 3-kinase results in a relocalization of V-ATPase from the plasma membrane to intracellular vesicles and consequent inhibition of bone resorption (41). PI 3-kinase also regulates V-ATPase assembly in cultured kidney cells where assembly is stimulated by glucose. PI 3-kinase inhibitors abolish this glucose-induced effect and expression of a constitutively active form of PI 3-kinase leads to a glucose-independent increase in V-ATPase assembly (24). It is possible that glycolytic flux may also function in regulating V-ATPase assembly in dendritic cells. Dendritic cells undergo a metabolic switch and experience increased glycolysis upon maturation by TLR agonists, presumably as a means to ensure that the bioenergetic resources are available to support the maturation program (42). This maturation-induced change in glycolytic metabolism is blocked by PI 3-kinase inhibitors. In kidney cells, the V-ATPase physically interacts with the glycolytic enzymes aldolase and phosphofructokinase (43–45). It is thus possible that glycolytic enzymes may be communicating changes in glycolytic flux to the V-ATPase upon maturation of dendritic cells.

Although our results place the V-ATPase downstream of mTOR signaling, recent work in HEK-293T cells and in hepatocytes suggests the V-ATPase may be upstream of mTOR activation (26, 46). It is possible that the increased V-ATPase assembly is functioning in a positive feedback mechanism to sustain mTOR activation and is thus also upstream of mTOR in the dendritic cell system. Experiments are underway to test this hypothesis.

Dendritic cell maturation is not an all-or-none response (47). The properties that constitute a fully mature dendritic cell are discrete, and thus, understanding the signaling pathways that regulate different elements of the maturation program is important. For example, treatment of dendritic cells with the helminth antigen Schistosoma mansoni egg antigen induces an acidification of lysosomal compartments independently of other maturation phenotypes such as expression of co-stimulatory molecules and production of cytokines (48). Ongoing efforts in our lab aim to separate the signaling pathways regulating V-ATPase assembly from those controlling other aspects of the maturation program.

In conclusion, we have shown that cluster disruption induces increased V-ATPase assembly in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. This process occurs rapidly and is mediated by PI 3-kinase/mTOR signaling. These results suggest that acidification of antigen processing compartments occurs in dendritic cells which promote immune tolerance as well as those which promote inflammation. They also identify a new process in mammalian cells in which regulated assembly of the V-ATPase plays a physiologically relevant role.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Capecci, Kristina Cotter, and Laura Stransky for many helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM34478 (to M. F.) and NIAID RO1 18919 (to M. J. S.). This work was also supported by a Sackler Dean's Fellow award (to R. L.).

S. Trombetta, personal communication.

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- V-ATPase

- vacuolar proton-translocating adenosine triphosphatase

- PI 3-kinase

- phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Banchereau J., Briere F., Caux C., Davoust J., Lebecque S., Liu Y. J., Pulendran B., Palucka K. (2000) Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 767–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sallusto F., Cella M., Danieli C., Lanzavecchia A. (1995) Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment: downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products. J. Exp. Med. 182, 389–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watts C., West M. A., Zaru R. (2010) TLR signaling regulated antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 22, 124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akira S., Takeda K. (2004) Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 499–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown J., Wang H., Hajishengallis G. N., Martin M. (2011) TLR-signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. J. Dent. Res. 90, 417–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Delamarre L., Holcombe H., Mellman I. (2003) Presentation of exogenous antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II molecules is differentially regulated during dendritic cell maturation. J. Exp. Med. 198, 111–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Banchereau J., Steinman R. M. (1998) Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392, 245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lutz M. B., Schuler G. (2002) Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 23, 445–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ocaña-Morgner C., Götz A., Wahren C., Jessberger R. (2013) SWAP-70 restricts spontaneous maturation of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 190, 5545–5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawiger D., Inaba K., Dorsett Y., Guo M., Mahnke K., Rivera M., Ravetch J. V., Steinman R. M., Nussenzweig M. C. (2001) Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 194, 769–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vander Lugt B., Beck Z. T., Fuhlbrigge R. C., Hacohen N., Campbell J. J., Boes M. (2011) TGF-β suppresses β-catenin-dependent tolerogenic activation program in dendritic cells. PLoS One 6, e20099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steinman R. M., Nussenzweig M. C. (2002) Avoiding horror autotoxicus: the importance of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 351–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riedl E., Stöckl J., Majdic O., Scheinecker C., Knapp W., Strobl H. (2000) Ligation of E-cadherin on in vitro-generated immature Langerhans-type dendritic cells inhibits their maturation. Blood 96, 4276–4284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trombetta E. S., Ebersold M., Garrett W., Pypaert M., Mellman I. (2003) Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science 299, 1400–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Forgac M. (2007) Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 917–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li S. C., Kane P. M. (2009) The yeast lysosome-like vacuole: endpoint and crossroads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 650–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown D., Paunescu T. G., Breton S., Marshansky V. (2009) Regulation of the V-ATPase in kidney epithelial cells: dual role in acid–base homeostasis and vesicle trafficking. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1762–1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kawasaki-Nishi S., Nishi T., Forgac M. (2001) Arg-735 of the 100-kDa subunit a of the yeast V-ATPase is essential for proton translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12397–12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirata T., Iwamoto-Kihara A., Sun-Wada G. H., Okajima T., Wada Y., Futai M. (2003) Subunit rotation of vacuolar-type proton pumping ATPase: relative rotation of the G and C subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23714–23719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imamura H., Nakano M., Noji H., Muneyuki E., Ohkuma S., Yoshida M., Yokoyama K. (2003) Evidence for rotation of V1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 2312–2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Toei M., Saum R., Forgac M. (2010) Regulation and isoform function of the V-ATPases. Biochemistry 49, 4715–4723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kane P. M. (1995) Disassembly and reassembly of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17025–17032 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parra K. J., Kane P. M. (1998) Reversible association between the V1 and V0 domains of yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase is an unconventional glucose-induced effect. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 7064–7074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beyenbach K. W., Wieczorek H. (2006) The V-type H+ ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 577–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sautin Y. Y., Lu M., Gaugler A., Zhang L., Gluck S. L. (2005) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated effects of glucose on vacuolar H+-ATPase assembly, translocation, and acidification of intracellular compartments in renal epithelial cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 575–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu Y., Parmar A., Roux E., Balbis A., Dumas V., Chevalier S., Posner B. I. (2012) Epidermal growth factor-induced vacuolar (H+)-ATPase assembly: a role in signaling via mTORC1 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26409–26422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dröse S., Bindseil K. U., Bowman E. J., Siebers A., Zeeck A., Altendorf K. (1993) Inhibitory effect of modified bafilomycins and concanamycins on P- and V-type adenosinetriphosphatases. Biochemistry 32, 3902–3906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Inaba K., Swiggard W. J., Steinman R. M., Romani N., Schuler G. (2001) Isolation of dendritic cells. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 3.7.1–3.7.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weber K., Osborn M. (1969) The reliability of molecular weight determinations by dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 4406–4412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Poltorak A., He X., Smirnova I., Liu M. Y., Van Huffel C., Du X., Birdwell D., Alejos E., Silva M., Galanos C., Freudenberg M., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Layton B., Beutler B. (1998) Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282, 2085–2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hirschfeld M., Ma Y., Weis J. H., Vogel S. N., Weis J. J. (2000) Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 165, 618–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zähringer U., Lindner B., Inamura S., Heine H., Alexander C. (2008) TLR2 – promiscuous or specific? A critical re-evaluation of a receptor expressing apparent broad specificity. Immunobiology. 213, 205–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang A., Bloom O., Ono S., Cui W., Unternaehrer J., Jiang S., Whitney J. A., Connolly J., Banchereau J., Mellman I. (2007) Disruption of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity 27, 610–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Legate K. R., Wickström S. A., Fässler R. (2009) Genetic and cell biological analysis of integrin outside-in signaling. Genes Dev. 23, 397–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rivard N. (2009) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: a key regulator in adherens junction formation and function. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 14, 510–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomson A. W., Turnquist H. R., Raimondi G. (2009) Immunoregulatory functions of mTOR inhibition. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 324–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leenen P. J., Radosević K., Voerman J. S., Salomon B., van Rooijen N., Klatzmann D., van Ewijk W. (1998) Heterogeneity of mouse spleen dendritic cells: in vivo phagocytic activity, expression of macrophage markers, and subpopulation turnover. J. Immunol. 160, 2166–2173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinman R. M., Lustig D. S., Cohn Z. A. (1974) Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice: III. Functional properties in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 139, 1431–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Granucci F., Ferrero E., Foti M., Aggujaro D., Vettoretto K., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. (1999) Early events in dendritic cell maturation induced by LPS. Microbes Infect. 1, 1079–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nakamura I., Sasaki T., Tanaka S., Takahashi N., Jimi E., Kurokawa T., Kita Y., Ihara S., Suda T., Fukui Y. (1997) Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase is involved in ruffled border formation in osteoclasts. J. Cell Physiol. 172, 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krawczyk C. M., Holowka T., Sun J., Blagih J., Amiel E., DeBerardinis R. J., Cross J. R., Jung E., Thompson C. B., Jones R. G., Pearce E. J. (2010) Toll-like receptor–induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood 115, 4742–4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lu M., Holliday L. S., Zhang L., Dunn W. A., Jr, Gluck S. L. (2001) Interaction between aldolase and vacuolar H+-ATPase: evidence for direct coupling of glycolysis to the ATP-hydrolyzing proton pump. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30407–30413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lu M., Sautin Y. Y., Holliday L. S., Gluck S. L. (2004) The glycolytic enzyme aldolase mediates assembly, expression, and activity of vacuolar H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8732–8739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Su Y., Zhou A., Al-Lamki R. S., Karet F. E. (2003) The a-subunit of the V-type H+-ATPase interacts with phosphofructokinase-1 in humans. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20013–20018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zoncu R., Bar-Peled L., Efeyan A., Wang S., Sancak Y., Sabatini D. M. (2011) mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H+-ATPase. Science 334, 678–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang Q., Liu D., Majewski P., Schulte L. C., Korn J. M., Young R. A., Lander E. S., Hacohen N. (2001) The plasticity of dendritic cell responses to pathogens and their components. Science 294, 870–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marshall F. A., Pearce E. J. (2008) Uncoupling of induced protein processing from maturation in dendritic cells exposed to a highly antigenic preparation from a helminth parasite. J. Immunol. 181, 7562–7570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]