Background: GLT-1c and EAAT5 are two excitatory amino acid transporters co-expressed in retinal neurons.

Results: GLT-1c and EAAT5 differ in glutamate and Na+ affinity, individual transport rates as well as in unitary anion current amplitudes.

Conclusion: GLT-1c and EAAT5 are optimized to fulfill different physiological tasks.

Significance: Identification of unitary channel properties underlying separate anion conductances associated with GLT-1c and EAAT5.

Keywords: Glutamate, Ion Channels, Neurotransmitter Transport, Patch Clamp, Retina, Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter

Abstract

In the mammalian retina, glutamate uptake is mediated by members of a family of glutamate transporters known as “excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs).” Here we cloned and functionally characterized two retinal EAATs from mouse, the GLT-1/EAAT2 splice variant GLT-1c, and EAAT5. EAATs are glutamate transporters and anion-selective ion channels, and we used heterologous expression in mammalian cells, patch-clamp recordings and noise analysis to study and compare glutamate transport and anion channel properties of both EAAT isoforms. We found GLT-1c to be an effective glutamate transporter with high affinity for Na+ and glutamate that resembles original GLT-1/EAAT2 in all tested functional aspects. EAAT5 exhibits glutamate transport rates too low to be accurately measured in our experimental system, with significantly lower affinities for Na+ and glutamate than GLT-1c. Non-stationary noise analysis demonstrated that GLT-1c and EAAT5 also differ in single-channel current amplitudes of associated anion channels. Unitary current amplitudes of EAAT5 anion channels turned out to be approximately twice as high as single-channel amplitudes of GLT-1c. Moreover, at negative potentials open probabilities of EAAT5 anion channels were much larger than for GLT-1c. Our data illustrate unique functional properties of EAAT5, being a low-affinity and low-capacity glutamate transport system, with an anion channel optimized for anion conduction in the negative voltage range.

Introduction

In the mammalian visual system, photoreceptors are depolarized in the dark. Exposure to light results in cell hyperpolarization and diminished glutamate release (1). Secondary active transporters rapidly remove glutamate from the synaptic cleft and thus permit the effective transmission of receptor potentials into electrical signals of bipolar cells.

Glutamate transporters belonging to the excitatory amino acid transporter (EAAT)2 family are crucial for glutamate uptake in the retina and thus for signal transmission during visual perception (2). EAAT1/GLAST mediates the uptake of glutamate into Müller cells (2–10), whereas EAAT2/GLT-1 is responsible for the glutamate transport into photoreceptors, bipolar and amacrine cells (4, 9, 10). Experiments with knock-out animals demonstrated profound effects on visual signal transmission upon EAAT1/GLAST removal, but only slight changes in EAAT2/GLT-1 knock-out animals (2). These data indicate that EAAT1/GLAST is the major retinal glutamate transporter that controls synaptic signal transmission, whereas EAAT2/GLT-1 mostly plays a role in neuroprotection against glutamate excitotoxicity. EAAT3/EAAC1 can be found in amacrine, ganglion, and horizontal cells (9, 11, 12) with predominant non-synaptic localization so that an important role in glutamatergic neurotransmission seems unlikely (13). EAAT4 has been identified in retinal astrocytes (9, 14) and in the retinal pigment epithelium (15). High affinity glutamate binding by EAAT4 (16) might serve as a back-up system preventing the escape of glutamate from beyond the bounds of the retina (9). EAAT5 is expressed in photoreceptors, bipolar, and amacrine cells. It is known to exhibit low glutamate transport rates and large anion conductances (17, 18) and has therefore been suggested to mainly act as glutamate-activated chloride channel to control the excitability of retinal neurons (17, 19–24).

GLT-1c is a splice variant of GLT-1/EAAT2 that is strongly and selectively expressed in the axon terminals of photoreceptors (10). During development, its expression is linked to the appearance of retinal dark currents, suggesting a functionally important role of this GLT-1 splice variant. So far, neither glutamate transport nor anion currents of GLT-1c have been studied. EAAT5 is almost retina-specific and co-expressed with GLT-1c in photoreceptor terminals. Whereas EAAT5 transport functions have already been characterized in detail (17, 18), a comprehensive study of the EAAT5 anion conductance is still lacking.

We cloned mouse GLT-1c (mGLT-1c) and mouse EAAT5 (mEAAT5) and studied transport and anion currents using whole-cell patch-clamp analyses in transfected HEK293T cells. We observed clear functional differences in both transporter functions, illustrating isoform-specific optimizations of glutamate transport and anion channel function in these two retinal EAAT isoforms.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning and Heterologous Expression of Mouse GLT-1c and Mouse EAAT5

Full-length mouse GLT-1c (mGLT-1c) was amplified from mouse retina cDNA using sequence specific sense and antisense primers with the following sequences: ATGGTCAGTGCCAACAATATGCCCA and CCCACGATTGATATTCCACATAATG. The PCR product was inserted into pGEM®-T Easy using TA cloning techniques of the pGEM®-T Easy Vector System (Promega). After transformation into OneShot®TOP10 competent cells, plasmid DNA was isolated with NucleoSpin Mini Kit (Macherey-Nagel). The 1674 base pair mGLT-1c product was confirmed by sequencing and published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (KC825358). For expression in mammalian cells, the coding region was inserted into pcDNA3.1(+) with the monomeric yellow fluorescent protein (mYFP) coding sequence linked to the 5′-end of the cDNA.

For cloning mouse EAAT5 (mEAAT5), RNA from the retina of 1-month-old WT C57BL6 mice was purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Tissue-specific mRNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the RevertAid M-MuL V Kit and oligo(dT)18 primers (Fermentas), and the mEAAT5 coding region was amplified using 2 μl of the cDNA product, 1 μl of Pfu polymerase (50 μl final volume) and sense and antisense primers (CACGTGGCCTGCTCTAATTT and GCGGAGACTCCAAAGACTTG). The blunt PCR product was 1707 base pairs in length, and the molecular sequence was in perfect agreement with the reference sequence of mouse EAAT5 (NP_666367.2) published at NCBI. The amplification product was inserted into pCRTM4Blunt-TOPO® using the Zero Blunt® TOPO® PCR Cloning Kit from Invitrogen and then subcloned with the mYFP coding sequence linked to the 5′-end of the cDNA encoding mEAAT5 into pcDNA3.1(+) using NotI and XbaI restriction sites. mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells as described previously (25). For each construct, two independent recombinants from the same transfection were examined and shown to exhibit indistinguishable functional properties.

Confocal Microscopy

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with mGLT-1c or mEAAT5 and cultivated on poly-l-lysine-treated glass coverslips. Attached cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and subsequently washed with 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Confocal imaging was carried out 2 days after transfection using a TCS SP5 II confocal laser-scanning setup (Leica Microsystems, Germany) with an inverted Leica DM6000 CFS confocal laser scanning microscope and a 63×/1.4 oil immersion objective. The mYFP was excited with a 488 nm argon laser. Images were recorded with Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence 2.6 and processed with FIJI (Fiji is just ImageJ 1.48f).

Electrophysiology

Standard whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Palo Alto, CA) (25, 26). Borosilicate pipettes were pulled with resistances of between 1.0 mΩ and 2.5 mΩ. In some experiments, pipettes were covered with dental wax to reduce their capacitance. Electrophysiological experiments were exclusively performed on cells that expressed mYFP-fusion proteins as observed by a Leica DM IL fluorescence microscope. To minimize voltage errors, we compensated at least 80% series resistance by an analog procedure and excluded cells with current amplitudes of more than 10 nA from the analysis. For the analysis of macroscopic currents, currents were filtered at 2 or 5 kHz and digitized with a sampling rate of 10 kHz using a Digidata AD/DA converter (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For the non-stationary noise analysis and the determination of relative open probabilities current traces were sampled at 50 kHz and filtered using a Bessel low-pass filter of 10 kHz. The standard external solution contained (mm): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES with or without 0.5 l-glutamate (Glu), whereas the standard internal solution was composed of (mm): 115 KNO3 or 115 NaNO3, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, and 10 HEPES. In experiments where K+ was used as internal cation, we added 5 mm tetraethylammonium chloride (TEACl) to the bath solution to suppress the activity of K+ channels. In the bath or internal solutions, the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH or KOH, respectively.

In some of the experiments we used modified internal and/or external solutions. For the determination of electrogenic glutamate transport currents, we used internal and external Cl− instead of NO3− or substituted permeable anions equimolarly with gluconate salts. For reverse glutamate transport, cells were internally dialyzed with a solution based on 115 mm Na-glutamate and externally perfused with (mm): 142 K-gluconate, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES. In K+-reduced solutions, we substituted K-gluconate with Na-gluconate. The anion selectivity was tested with a standard internal solution containing 115 mm NaNO3 and standard bath solutions containing 0.5 mm glutamate and Cl−, NO3− or SCN− as the main external anion. To determine the sodium dependence of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5-mediated currents, we equimolarly substituted Na-chloride with choline chloride and recorded currents in the presence of 1 mm glutamate. Current measurements to determine relative open probabilities and for non-stationary noise analysis were performed in symmetrical NO3−, with 0.5 mm external glutamate and Na+ as the main internal cation.

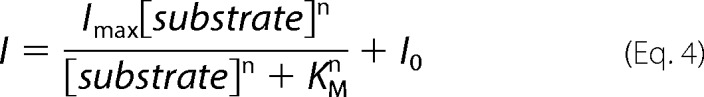

Noise Analysis

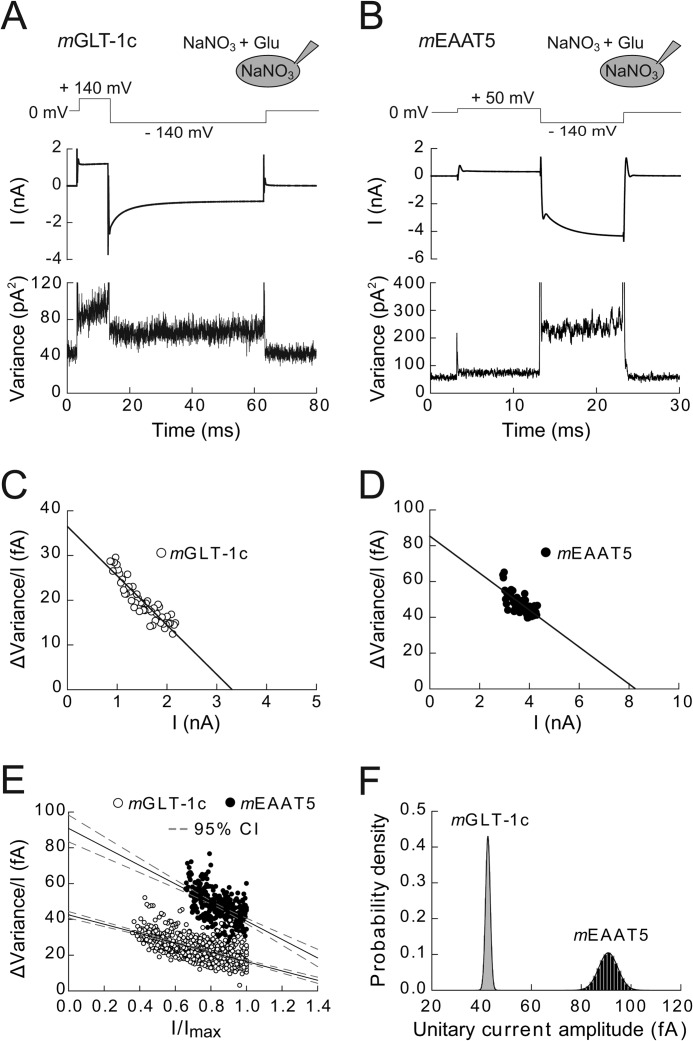

Non-stationary noise analysis was used to determine the single-channel current amplitudes of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion channels (Fig. 5) (26, 27). We calculated current variances during 300 subsequent voltage jumps from a positive prepulse to −140 mV from current differences in subsequent records at each time point to reduce the artifacts arising from small linear shifts during the measurement protocol (27). After subtracting the background noise (measured at the reversal potential) and discretizing variances into 50 current bins, we plotted the ratio of the variance by the mean current amplitude versus the mean current amplitude at various time points for individual cells (Fig. 5, C and D).

FIGURE 5.

Unitary current amplitudes of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion channels determined by non-stationary noise analysis. A and B, voltage protocol and time courses of mean current amplitudes and current variances from cells expressing mGLT-1c (A) or mEAAT5 (B) measured in symmetrical NaNO3-based solutions. C and D, linear transformation of current-variance plots from the recordings shown in A and B. Solid lines provide fits with linear functions (Equation 2). E, pooled noise analysis data from 13 cells expressing mGLT-1c (white circles) and 6 cells expressing mEAAT5 (black circles). For comparison between different cells, current variance by mean current amplitude ratios are plotted against normalized current amplitudes. Solid lines represent fits with a linear function (Equation 3), and dashed lines give the 95% confidence interval of the fit determined by bootstrap regression analysis. F, distribution of estimated unitary current amplitudes for mGLT-1 and mEAAT5 derived from 50.000 bootstrap samples of the original data. Histograms have been normalized such that the integral over the range is 1 and fitted with a Gaussian function (mGLT-1c: μ = 42.5, σ = 0.9; mEAAT5: μ = 90.8, σ = 3.9).

Current artifacts in individual sweeps might cause overestimation of mEAAT5 or mGLT-1c current noise. To identify such sweeps we performed a systematic analysis of such artifacts and found that exclusion of all difference sweeps with time-averaged variances higher than the double overall variance of all sweeps resulted in stable and converging fit parameters that were not affected by removal of further outliers. We routinely applied this threshold value that removed of 5–10% of all sweeps.

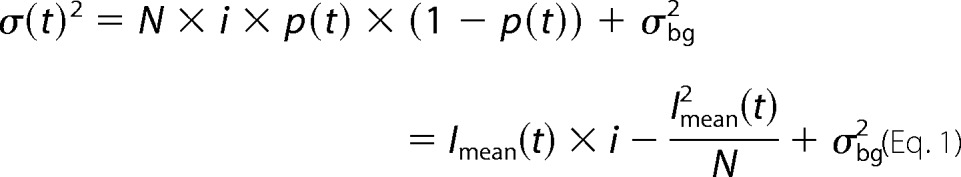

Ion channels usually generate a Lorentzian-type of noise. Since open and closed states of an ion channel are binomially distributed, the amplitude, and the time dependence of the current variance (σ2) can be calculated by Equation 1,

|

or after linear transformation, Equation 2,

|

with i being the single-channel current amplitude, p the absolute open probability, N the total number of channels in the membrane, Imean the mean macroscopic current amplitude and σ2bg the voltage-independent background noise. The y axis intercept from a linear regression of Equation 2 to the data points thus provides the unitary current amplitude, and the slope of the linear regression (−N−1) gives an approximation of the number of channels.

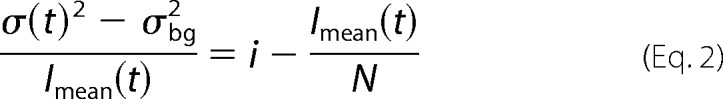

We first performed this analysis on the data of individual cells and obtained consistent results. However, to estimate the uncertainty of the single-channel current estimate from noise analysis as precisely as possible, we pooled data from all cells expressing mEAAT5 or mGLT-1c into single plots. To compare data from different cells with varying numbers of channels (N) and different whole-cell current amplitudes, mean currents (Imean) were normalized to the maximum current amplitudes (Imax) observed during the voltage jump experiment, and ratios of current variances by non-normalized current amplitudes were plotted versus normalized current amplitudes for all examined cells (Fig. 5E) in Equation 3.

|

This normalization allows fitting of Equation 3 to all data points and assessing the regression error using bootstrap sampling simulations (28). Bootstrap sampling has been shown to yield better estimates of the regression error than the conventional methods using approximated covariance matrices of the regression parameters (28). It furthermore allows definition of 95% confidence intervals of the fit by ordering the regression lines of all bootstrap samples along the y axis and identifying 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles.

50.000 bootstrap samples were resampled by randomly selecting observations from the original data sets of mEAAT5 and mGLT-1c with replacement. We determined single-channel amplitudes for all bootstrap samples and the distribution of these values was plotted in a histogram for visual inspection (Fig. 5F). Single-channel current amplitudes are given as mean ± standard deviation of the distribution of this parameter after regression of all bootstrap samples.

Data Analysis

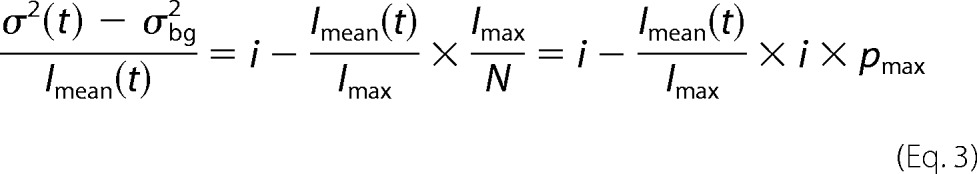

Data were analyzed with a combination of pClamp 10.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), SigmaPlot 11 programs (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA) and self-written Python programs. Steady-state current amplitudes were used without any subtraction procedure. The relative errors for apparent dissociation constants were obtained as standard errors of fit estimates by fitting Hill equations to the concentration dependence of mGLT-1c or mEAAT5-mediated currents (Fig. 3) in Equation 4.

|

The substrate-dependent (Imax) and substrate-independent current amplitudes (I0) and the Hill coefficient (n) were determined as fit parameters. Steady-state currents measured as function of [l-glutamate] were normalized to the current in the presence of 2 mm l-glutamate, whereas sodium-dependent currents were normalized to the current recorded at 200 mm external Na+.

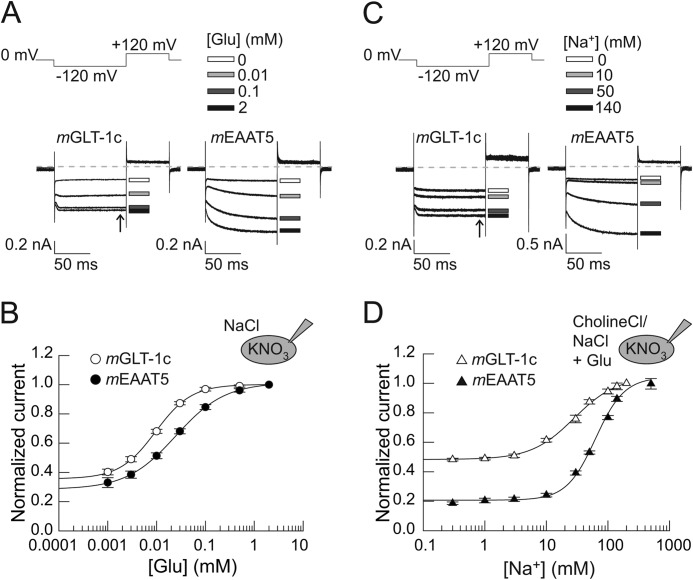

FIGURE 3.

Glutamate and sodium dependences of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5. A, representative current responses of cells expressing mGLT-1c (left) or mEAAT5 (right) to the application of bath solutions containing 140 mm NaCl with different concentrations of external glutamate (shown are [Glu] of 0 mm = white rectangle, 0.01 mm = light gray rectangle, 0.1 mm = dark gray rectangle or 2 mm = black rectangle) at −120 mV. K+ was used as internal cation. Dotted lines represent 0 nA. B, glutamate concentration dependences of steady-state currents (arrow in Fig. 3A) of mGLT-1c (white circles) and mEAAT5 (black circles). Currents are fitted with a Hill equation, providing Km values of 9.6 ± 0.3 μm for mGLT-1c (Hill coefficient = 1.2 ± 0.04, n = 6) and 24.7 ± 0.4 μm (Hill coefficient = 0.9 ± 0.01; n = 5) for mEAAT5. C, whole-cell currents of mGLT-1c (left) and mEAAT5 (right) recorded in bath solutions containing 1 mm glutamate at different concentrations of external sodium (shown are [Na+] of 0 mm = white rectangle, 10 mm = light gray rectangle, 50 mm = dark gray rectangle or 140 mm = black rectangle) and a standard internal solution of KNO3 at a voltage step of −120 mV. Dotted lines represent 0 nA. D, corresponding sodium concentration dependences of steady-state currents (arrow in Fig. 3C) of mGLT-1c (white triangles) and mEAAT5 (black triangles). Currents are fitted with a Hill equation, providing Km values of 62.8 ± 4.3 mm (Hill coefficient = 1.9 ± 0.2; n ≥ 3) for mEAAT5 and 28.4 ± 2.3 mm (Hill coefficient = 1.2 ± 0.1, n = 5) for mGLT-1c.

To determine the voltage dependence of relative open probabilities of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion channels, isochronal current amplitudes were measured at −130 mV after 150 ms prepulses immediately after the capacitive current relaxation (< 500 μs after the voltage step), normalized to maximum values and plotted versus the prepulse potential (Fig. 6).

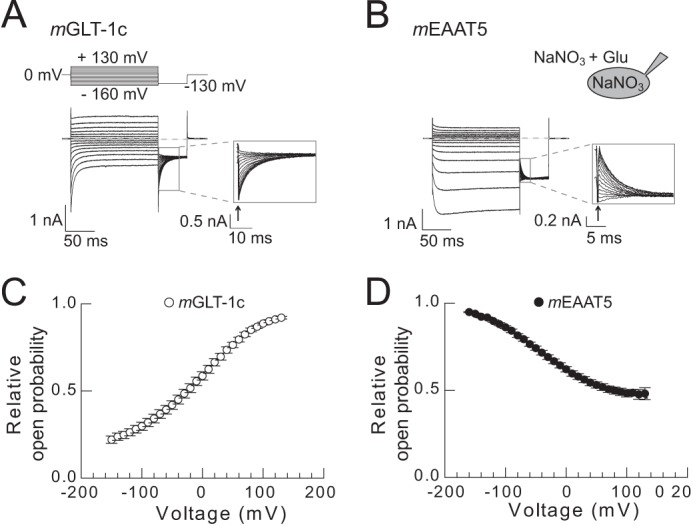

FIGURE 6.

Voltage dependence of the relative open probabilities of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion channels. A and B, representative whole-cell measurements of cells expressing (A) mGLT-1c or (B) mEAAT5 performed in symmetrical NaNO3. Insets depict the magnification of the tail currents recorded at −130 mV. C and D, relative open probabilities of (C) mGLT-1c (n = 11) and (D) mEAAT5 (n = 7) anion channels in the presence of glutamate.

For statistical evaluations Student's t test and paired t test with p ≤ 0.05 (*) as the level of significance were used (p ≤ 0.01 (**), p ≤ 0.001 (***), ns = not significant).

Single-channel current amplitudes are given as mean ± standard deviation of fit results from bootstrap samples. All other data are presented as mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 Express Robustly in Transiently Transfected HEK293T Cells

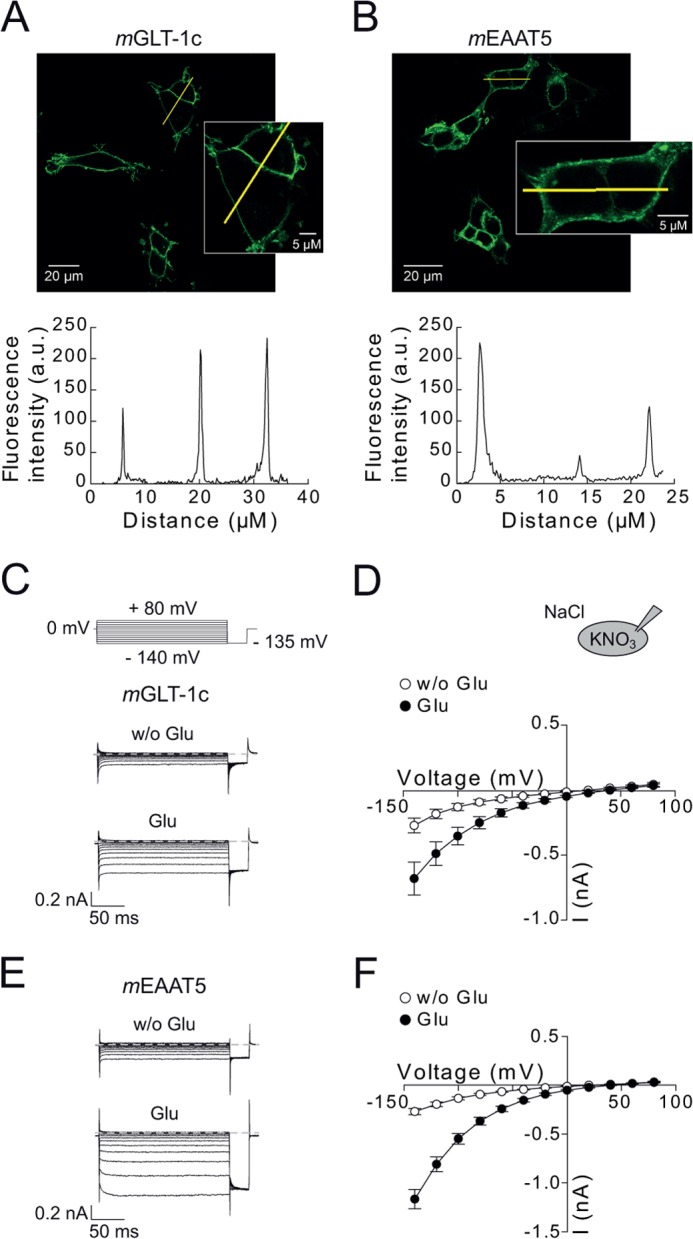

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 might differ in expression levels as well as in the subcellular distribution when heterologously expressed in HEK293T cells. Profound differences in these parameters would affect the comparison of transport functions. We expressed mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 as mYFP fusion protein and examined transfected cells by confocal imaging (Fig. 1, A and B). Both transporters were located in the surface membrane. Cells transfected with identical DNA amounts of mGLT1c or mEAAT5-exhibited comparable fluorescence amplitudes (Fig. 1, A and B, bottom). Whereas cells expressing mGLT-1c showed almost exclusive staining of the surface membrane (Fig. 1A, inset) we observed additional staining of intracellular compartments in mEAAT5-expressing cells (Fig. 1B, inset).

FIGURE 1.

Subcellular localization and functional properties of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5. A and B, confocal images and corresponding intensity profiles of cells expressing mYFP-mGLT-1c (A) or mYFP-mEAAT5 (B). Insets show a magnification of selected cells. C and E, representative whole-cell currents from cells expressing mGLT-1c (C) or mEAAT5 (E) recorded with 115 mm internal KNO3 and bath solution containing 140 mm NaCl in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of 0.5 mm glutamate. Dotted lines indicate 0 nA. D and F, corresponding current-voltage relationship for (D) mGLT-1c (n = 7) and (F) mEAAT5 (n = 8) without (white circles) and with (black circles) external glutamate.

In all cells, fluorescent staining of nuclei was absent. Moreover, electrophoresis of cleared lysates by reducing SDS-PAGE and visualization of mYFP-tagged proteins with a fluorescence scanner (29) (data not shown) demonstrated, that mYFP is predominantly expressed as mGLT1c or mEAAT5 fusion protein. These two results indicate that expression levels and subcellular distributions can be accurately studied by fluorescence imaging. We conclude that expression levels of mGLT1c or mEAAT5 are comparable in transfected HEK293T cells.

Glutamate Uptake and Anion Conduction by mGLT-1c and mEAAT5

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 were functionally characterized as mYFP fusion proteins through whole-cell patch clamping of transiently transfected HEK293T cells. This procedure permits identification of transfected cells and selection of cells with high expression levels by fluorescence microscopy. Fig. 1 shows representative current recordings from HEK293T cells expressing mGLT-1c (Fig. 1C) or mEAAT5 (Fig. 1E). Cells were internally dialyzed with KNO3-based solutions and consecutively exposed to glutamate-free and glutamate-containing solutions. These conditions permitted transitions through all functional transporter states and increased anion currents to levels significantly above leak and endogenous current amplitudes. We observed robust mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion currents in the absence of glutamate, indicating glutamate-independent anion currents. The application of glutamate increased mGLT-1c currents ∼2-fold (Fig. 1, C and D) and mEAAT5 currents 4-fold (Fig. 1, E and F). With potassium as the internal cation, currents mediated by mGLT-1c were almost time-independent, whereas mEAAT5 currents activated at hyperpolarizing voltage steps.

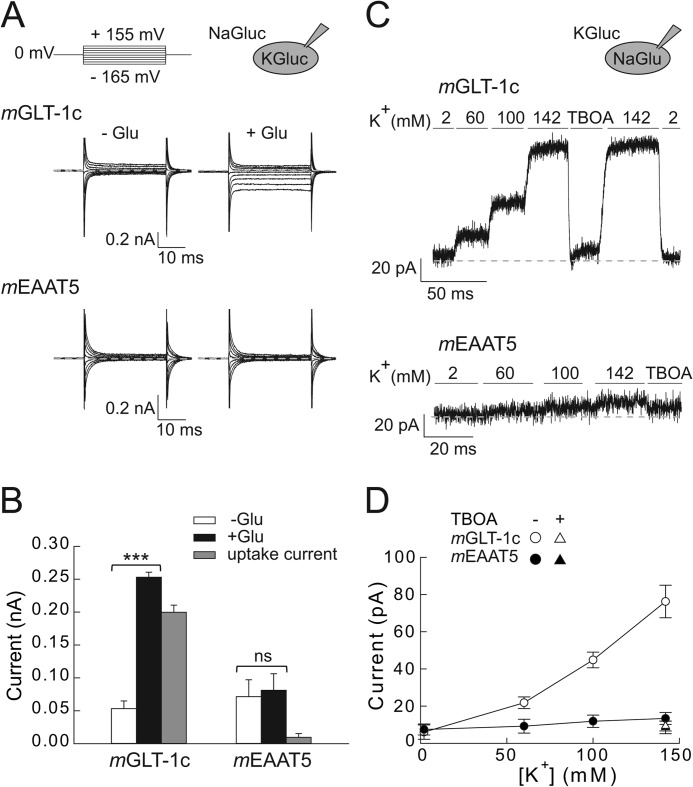

Glutamate-dependent currents consist of the uptake current generated by the electrogenic coupled glutamate transport and of the glutamate-sensitive anion current component. To evaluate the contribution of glutamate transport current to the total current amplitude, we substituted intracellular NO3− and extracellular Cl− equimolarly with the impermeable anion gluconate and recorded currents of mGLT-1c (Fig. 2A, top) or mEAAT5 (Fig. 2A, bottom) in the absence and presence of 0.5 mm glutamate. In glutamate-free solution, nearly no current could be detected for mGLT-1c at positive or negative potentials. Saturating glutamate concentrations elicited significant currents at negative voltage steps, but not at positive potentials. In cells expressing mEAAT5, no current was induced by glutamate in the absence of permeable anions. Glutamate uptake currents (Fig. 2B) were calculated by subtracting whole-cell currents of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 recorded in the absence of glutamate from currents measured in the same cell after application of glutamate. Whereas mGLT-1c displayed prominent electrogenic glutamate uptake, uptake by mEAAT5 was below the resolution limit of our experimental approach.

FIGURE 2.

Forward and reverse glutamate transport of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5. A, whole-cell currents of mGLT-1c (top) and mEAAT5 (bottom) recorded under conditions favoring forward glutamate transport. Cells were dialyzed with 115 mm K-gluconate and externally perfused with anion-free solution containing 142 mm Na-gluconate without (left) or with (right) 0.5 mm glutamate. B, mean steady-state current amplitudes of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 recorded with gluconate-based internal and external solutions at a voltage of −165 mV. Glutamate uptake currents (gray bars) of mGLT-1c (n = 5) or mEAAT5 (n = 6) were determined by subtracting currents in the absence of external glutamate (white bars) from currents elicited by 0.5 mm glutamate (black bars). C, reverse glutamate transport currents of mGLT-1c (top) and mEAAT5 (bottom) induced by 115 mm internal Na-glutamate and the application of 2 mm, 60 mm, 100 mm, or 142 mm external K+ or 142 mm K+ + 50 μm TBOA at a constant voltage step of 0 mV. Dotted lines represent 0 pA. D, K+ dependence of the reverse glutamate transport of mGLT-1c (n = 7) (white symbols) and mEAAT5 (n = 6) (black symbols) in the absence (circles) and presence (triangles) of 50 μm TBOA at 0 mV.

We recently identified C-terminal truncations that abolish forward glutamate transport, but leave backward transport by the human EAAT2 unaffected (30). To test whether mGLT-1c or mEAAT5 exhibit a similar difference in transport rates for backward and forward glutamate transport, we internally dialyzed cells expressing mGLT-1c (Fig. 2C, top) or mEAAT5 (Fig. 2C, bottom) with solutions containing 115 mm Na-glutamate and applied bath solutions with varying concentrations of K+ (2, 60, 100, or 142 mm). Whole-cell currents were recorded at 0 mV, and the contribution of anion channels to the measured current amplitudes were minimized by substituting internal Cl− with glutamate and external Cl− with gluconate. For mGLT-1c, a K+-dependent outward current was observed under these conditions (Fig. 2, C and D), which increased with [K+] and was reversibly blocked by the application of 50 μm external dl-threo-β-benzyloxyaspartate (TBOA) (I142 mm K+ = 76.3 ± 8.8 pA; I TBOA = 9.3 ± 2.6 pA; n = 7). These results indicate that mGLT-1c effectively mediates forward as well as reverse glutamate transport.

For mEAAT5, no reverse glutamate transport could be detected (Fig. 2, C and D). In cells expressing mEAAT5 changes of external [K+] from 0 mm to 142 mm resulted only in negligible current increases, and current amplitudes in presence of 142 mm K+ were not different from currents recorded in presence of 50 μm TBOA (I142 mm K+ = 13.4 ± 3.2 pA; ITBOA = 8.6 ± 3.4 pA; n = 6). Taken together these results demonstrate that mEAAT5 mediates neither effective forward nor reverse glutamate transport.

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 Currents Display Distinct Glutamate and Sodium Dependences

Fig. 3A shows representative whole-cell recordings of mGLT-1c (left) and mEAAT5 (right) in glutamate-free solution or selected concentrations of 0.01 mm, 0.1 mm, or 2 mm glutamate at a constant voltage step of −120 mV. The concentration dependence of steady-state currents of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 could be fit with a Hill equation (Fig. 3B), providing Km values of 9.6 ± 0.3 μm (Hill coefficient = 1.2 ± 0.04, n = 6) for mGLT-1c and 24.7 ± 0.4 μm (Hill coefficient = 0.9 ± 0.01, n = 5) for mEAAT5. For mGLT-1c and for mEAAT5 a similar fraction of the maximum current at 2 mm external glutamate was observed in the absence of glutamate, 35 ± 2% (mGLT-1c, n = 6) or 28 ± 3% (mEAAT5, n = 5). Glutamate binding requires the presence of extracellular sodium. Fig. 3C shows representative current responses of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5, which were recorded with internal KNO3 and bath solutions containing 1 mm glutamate with various concentrations of external Na+ (0 mm, 10 mm, 50 mm, or 140 mm) at −120 mV. Under these conditions, we detected an apparent dissociation constant of 28.4 ± 2.3 mm (Hill coefficient = 1.2 ± 0.1, n = 5) for mGLT-1c (Fig. 3D). For mEAAT5, we had to increase the external sodium concentration up to 500 mm to reach saturating conditions and we determined a Km value of 62.8 ± 4.3 mm (Hill coefficient = 1.9 ± 0.2, n ≥ 3), which is in the same range as the value previously reported for the hEAAT5 (18).

Relative current amplitudes in the absence of external Na+ were different for mGLT-1c and mEAAT5. Whereas relative current amplitudes in the absence of sodium were only 21 ± 1% (n ≥ 3) of the maximum current amplitude at saturating concentrations of sodium in mEAAT5, the contribution of the sodium-independent current to the total current was relatively high in mGLT-1c (49 ± 1%, n = 5). We recently demonstrated that hEAAT2 anion channels are active even in the combined absence of glutamate and sodium, verifying a unique sodium dependence of this isoform (30). Our present results indicate that this particular property of EAAT2 is preserved in mGLT-1c.

mEAAT5 and mGLT-1c Anion Channels Display Identical Anion Selectivity

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 represent extreme examples of isoform-specific differentiation into effective transporters with small associated anion currents or low-capacity transporters with predominant anion conductance, respectively (16). The low EAAT5 glutamate transport rates have been recently assigned to small Na+-association rates (18). At present, it is not known whether the predominance of EAAT5 anion currents is simply caused by the ineffective glutamate transport or is due to unique properties of the underlying anion channels.

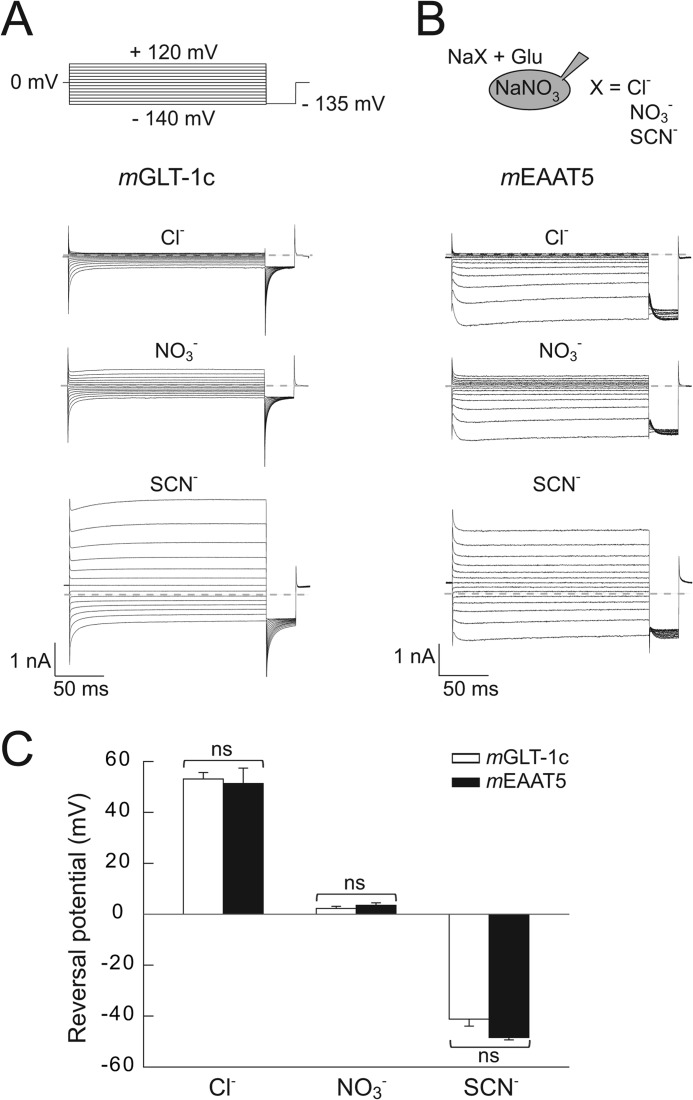

To test for isoform-specific differences in anion selectivity, current reversal potentials were determined in perfusion experiments with external Cl−, NO3−, or SCN−, and NO3−-based internal solutions (Fig. 4). In these experiments, we substituted internal K+ with Na+ to abolish coupled transport, which significantly contributes to the macroscopic current in mGLT-1c, resulting in a deactivation of mGLT-1c and activation of mEAAT5 anion currents upon hyperpolarization.

FIGURE 4.

Anion selectivity of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion currents. A and B, current responses of cells expressing (A) mGLT-1c or (B) mEAAT5 to the application of 140 mm Na+-based bath solutions containing various anions (Cl−, NO3−, or SCN−) and 0.5 mm external glutamate. Cells were internally dialyzed with 115 mm NaNO3. Dotted lines represent 0 nA. C, the effect of external anions on the reversal potential of currents mediated by mGLT-1c (n = 6) (white bars) or mEAAT5 (n = 4) (black bars). The statistical significance was evaluated with Student's t test (ns = not significant).

With Cl− as external anion, currents of mGLT-1c (Fig. 4A) or mEAAT5 (Fig. 4B) reversed at +53.1 ± 2.6 mV (n = 6) or +51.3 ± 6 mV (n = 4), respectively. For external NO3−, reversal potentials of 2.3 ± 0.8 mV (mGLT-1c, n = 6) or 3.5 ± 1.0 mV (mEAAT5, n = 4) were determined, whereas the application of the more permeable anion SCN− led to a shift in reversal potentials to negative values (−41.2 ± 2.7 mV for mGLT-1c, n = 6; −48.5 ± 0.9 mV for mEAAT5, n = 4). No statistically significant difference in the reversal potentials of mGLT-1c or mEAAT5-mediated currents (Fig. 4C) was detected in these experiments, indicating comparable anion selectivity for mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion channels. For both transporters, changing the predominant external anion caused only slight alterations in the time and voltage dependence of the anion currents.

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 Differ in Unitary Anion Channel Conductance and Relative Open Probability

We next employed non-stationary noise analysis to determine unitary current amplitudes of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 anion channels. Fig. 5 shows time courses of the mean macroscopic currents and the corresponding current variances for mGLT-1c (A) and mEAAT5 (B) elicited by repetitive voltage steps of −140 mV in symmetrical NO3− and 0.5 mm external glutamate. Ratios of the current variance by the mean current amplitude plotted against the mean current amplitude at various time points after the hyperpolarizing voltage step were fitted with a linear function (Equation 2) providing the single-channel current amplitudes as fitted y axis intercept (Fig. 5, C and D) (31). Whereas mGLT-1c exhibits a unitary current amplitude of 43 ± 1 fA (n = 13) at −140 mV (Fig. 5C), the single-channel current amplitude of mEAAT5 anion channels was more than 2-fold larger (89 ± 3 fA (n = 6)) (Fig. 5D).

To confirm the validity of these fit results, we repeated the noise analysis through linear regression on a pooled data set from all cells. Unitary current amplitudes can be also determined from plots of the variance/current amplitude ratio versus the normalized current amplitude to permit comparisons between cells with different numbers of transporters. Fig. 5E shows such a plot for all cells expressing either mGLT-1c (white circles) or mEAAT5 (black circles), with current amplitudes normalized to maximum current amplitudes at −140 mV at the same cell. Comparison between the two isoforms reveals larger variance/current amplitude ratios for mEAAT5 than for mGLT-1 at comparable absolute open probabilities, in full agreement with higher unitary current amplitudes for mEAAT5 (Fig. 5E).

From the original data set, 50.000 bootstrap samples (each containing 650 mGLT1c or 300 mEAAT5 data points) were randomly resampled with replacement (28) and individually analyzed by regression with a linear function (Equation 3). Bootstrap analysis simulates the error-generating process of data sampling from a larger population and thus permits approximation of the true error of fit parameters. For each bootstrap sample, single-channel current amplitudes were determined as y axis intercept from this fit providing a single channel current amplitude of 43 ± 1 fA for mGLT-1c and 91 ± 4 fA for mEAAT5 (Fig. 5, E and F). The bootstrap analysis allowed for the definition of the 95% confidence intervals of the regression lines and regression parameters (mGLT-1c: [40.7, 44.4]; mEAAT5: [83.4, 98.3]) and demonstrated the statistical significant difference (p < 0.0001) of the single-channel conductance of the two isoforms (Fig. 5F).

mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 also differ in the relative open probabilities of anion channels (Fig. 6). Relative open probabilities of anion channels were determined by plotting normalized isochronal current amplitudes at a voltage step of −130 mV versus the preceding potential (Fig. 6, A and B). Anion channels of mGLT-1c (Fig. 6C) displayed a higher relative open probability at positive potentials, while anion channels of mEAAT5 (Fig. 6D) closed at depolarizing voltage steps and opened at voltages to more negative potentials.

DISCUSSION

In the mammalian retina, all known EAATs are expressed (often with more than one isoform in a particular cell type) suggesting distinct functional tasks of various EAATs in visual synaptic transmission. To gain deeper insights into a possible functional specialization of EAATs at presynaptic terminals of retinal neurons, we cloned two transporters co-expressed in photoreceptors, mGLT-1c and mEAAT5, and compared glutamate transport and anion conduction using identical experimental approaches in the same expression system.

GLT-1c is a splice variant of GLT-1/EAAT2 (10). We found that mGLT-1c effectively transports glutamate with high affinity for glutamate and Na+ binding, closely similar to GLT-1/EAAT2 (30, 32). This finding supports the notion that alternate splicing might modify the targeting of GLT-1 to distinct membrane domains (10), but does not necessarily confer novel functional properties. For mEAAT5 the glutamate transport activity was (in the forward as well as in the reverse transport mode) below the resolution limit of whole-cell recording. Moreover, the affinity for glutamate and Na+ determined as the substrate dependence of anion currents was much lower than for mGLT-1c. These data closely resemble earlier results on hEAAT5 (17, 18), as expected regarding the high degree of sequence identity of mouse and human EAAT5. Glutamate transport rates of individual transporters are very difficult to determine. The absence of measurable glutamate transport in cells expressing mEAAT5 could in principal be due to a negligible number of transporters in the surface membrane of transfected cells. However, confocal imaging shows clear surface membrane staining of mYFP-mEAAT5, with fluorescence intensity in the range of cells expressing mYFP-mGLT-1c (Fig. 1). Moreover, robust mEAAT5 anion currents (Figs. 4 and 6) directly demonstrate a substantial number of mEAAT5 in the surface membrane of investigated cells.

To permit comparison of anion conductances of distinct EAAT isoforms, anion current amplitudes are often normalized to glutamate transport currents obtained at the same cell. This analysis revealed much smaller relative anion currents for EAAT1, EAAT2, and EAAT3 than for EAAT4 and EAAT5 (17, 33, 34). Since separate EAAT isoforms differ in the glutamate transport rate, variation in these relative values could be exclusively due to a difference in glutamate transport (16) and thus do not allow comparison of unitary current amplitudes of distinct EAAT anion channels. To determine single EAAT anion channel current amplitudes, stationary as well as non-stationary noise analysis has been used in recent years. Initially, EAAT anion channels were considered to be closed in the absence of glutamate, and current variances in the absence of glutamate were subtracted as background noise. These early experiments provided largely varying unitary current amplitudes ranging from a few fA for EAAT1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes (35) over values in the range of the results of the present study in photoreceptors (36) to several pA in bipolar cells from goldfish retina (22). These pronounced differences were interpreted in terms of substantial isoform-specific variation in unitary anion current amplitudes. Later, expression of EAATs in mammalian cells permitted experiments with large EAAT anion currents and negligible background currents. Such experiments demonstrated that EAAT anion channels are active also in the absence of glutamate and revealed significant current relaxations upon voltage steps (25, 30, 37, 38). Our group used voltage-dependent gating of EAAT anion currents for non-stationary (25, 39) and stationary noise analysis at different potentials (37, 38, 40). Unfortunately, non-stationary noise analysis requires significant stimulus-dependent changes in absolute open probabilities and is therefore not always possible. Stationary noise analysis requires assumptions about the voltage dependence of unitary current amplitudes and is particularly viable to incorrect determination of background variances.

For the present study we decided to compare mGLT-1c and mEAAT5 using non-stationary noise analysis. Using this approach, we determined mEAAT5 single anion channel conductances that were about twice as large as the value determined for mGLT-1c. Comparable measurements were also performed for rEAAT4, with a unitary current amplitude of 25 fA at −150 mV.3 For EAAT1 and EAAT3, such measurements are missing, however, stationary noise analysis at other ionic conditions demonstrated similar unitary anion current amplitudes for EAAT3 and EAAT4 (37). Taken together, these experiments provide EAAT anion current amplitudes decreasing in the order EAAT5 > EAAT2 > EAAT4 ∼ EAAT3. Although EAAT4 and EAAT5 both appear to mainly function as anion channels, single EAAT5 anion currents are roughly four times larger than those of EAAT4. Moreover, mGLT-1c, a prototypic EAAT isoform with small macroscopic anion conductance exhibits unitary anion current amplitudes that are larger than those of EAAT4 (16, 33). These data demonstrate that the dramatic differences in relative anion conductance between EAAT1–3 and EAAT4, 5 are not purely caused by isoform-specific unitary anion current amplitudes. In fact, unitary current amplitudes of separate EAAT anion channels differ less than for example those of various voltage-gated K+ channels or ClC channels (41). Anion selectivities are very similar among different EAATs (25, 34, 35) (Fig. 4). Taken together, these functional data support the notion that all mammalian EAATs utilize a conserved anion conduction pathway.

Grewer et al. recently provided a detailed kinetic analysis of currents of the hEAAT5 (18). Using rapid application of transport substrates the authors demonstrated that the low transport rate of EAAT5 is caused by very slow Na+ association to the glutamate-free transporter. Upon hyperpolarizing voltage steps a slow conformational change precedes opening of the anion channels and explains the experimentally observed anion channel activation at negative voltages. Differences in Na+ association likely account for the marked differences in mGLT1c/EAAT2 and mEAAT5 anion channel gating (Fig. 1).

The physiological role of EAAT5 is still insufficiently understood. Its low glutamate transport rate and glutamate affinity argue against a major role in glutamate reuptake, and EAAT5 was therefore always assumed to function as a glutamate-gated anion channel. However, experimental validation of this suggestion is still missing. No animal models lacking EAAT5 have been reported, and, so far, no human disease has been linked to mutations in SLC1A7 that might have allowed an unambiguous identification of a cellular function of EAAT5.

Recent work assigned presynaptic anion currents in native rod and cone photoreceptor terminals to EAAT5 (23). The high unitary current amplitudes together with the maximum open probability of anion channels at negative potentials enable EAAT5 to mediate large Cl− currents at physiological potentials. Activation of presynaptic EAATs by glutamate can stimulate or inhibit the activity of Ca2+ channels depending on the intracellular [Cl−]. In cones of the salamander retina, Cl− efflux through EAAT5 might support the depolarization of the cell and activate Ca2+ channels for further glutamate release (42). On the other hand, low internal Cl− concentrations in rods have been shown to inhibit Ca2+ channels and to cause a reduction of glutamate release (43). The particularly low affinity of EAAT5 for transporter substrates, as well as the lower open probability of EAAT5 anion channels at depolarizing membrane potentials could prevent an early inhibition of Ca2+ currents by EAAT5 when synaptic transmission starts and extracellular glutamate levels are low.

EAAT5 is also expressed in axon terminals of bipolar cells. Bipolar cells exhibit a somatodendritic chloride gradient that might serve inversion of GABAergic horizontal cell input (44). We recently reported that a naturally occurring mutation found in a patient with episodic ataxia type 6 modifies the gating of EAAT1 (38, 45), resulting in a profound inward-rectification, and we postulated that P290R EAAT1 might affect intracellular anion concentrations in Bergmann glia. The gating of EAAT5 closely resembles gating of P290R EAAT1 anion channels, and it is thus tempting to speculate that EAAT5 might fulfill a similar function in retinal neurons.

In summary, this study provides a first detailed functional characterization of transport and anion conduction properties of mGLT-1c and mEAAT5. Whereas mGLT-1c exhibits functional properties well suited for effective glutamate clearance, mEAAT5 is a low-capacity and low-affinity glutamate transporter with an associated anion channel that is optimized for conducting large anion currents at negative potentials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Ewers, Jasmin Hotzy, Peter Kovermann, and Ariane Leinenweber for helpful discussions, and Petra Kilian and Toni Becher for excellent technical assistance.

These studies were supported by the Deutsche Forschungs-gemeinschaft FA301/9 (to Ch. F.).

J. P. Machtens, unpublished observation.

- EAAT

- excitatory amino acid transporter

- GLT

- glutamate transporter

- TEACl

- tetraethylammonium chloride

- TBOA

- dl-threo-β-benzyloxyaspartate

- GLAST

- l-glutamate/l-aspartate transporter.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dacheux R. F., Miller R. F. (1976) Photoreceptor-bipolar cell transmission in the perfused retina eyecup of the mudpuppy. Science 191, 963–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harada T., Harada C., Watanabe M., Inoue Y., Sakagawa T., Nakayama N., Sasaki S, Okuyama S., Watase K., Wada K., Tanaka K. (1998) Functions of the two glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT-1 in the retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4663–4666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Derouiche A., Rauen T. (1995) Coincidence of L-glutamate/L-aspartate transporter (GLAST) and glutamine synthetase (GS) immunoreactions in retinal glia: evidence for coupling of GLAST and GS in transmitter clearance. J. Neurosci. Res. 42, 131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rauen T., Rothstein J. D., Wässle H. (1996) Differential expression of three glutamate transporter subtypes in the rat retina. Cell Tissue Res. 286, 325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rauen T., Taylor W. R., Kuhlbrodt K., Wiessner M. (1998) High-affinity glutamate transporters in the rat retina: a major role of the glial glutamate transporter GLAST-1 in transmitter clearance. Cell Tissue Res. 291, 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lehre K. P., Davanger S., Danbolt N. C. (1997) Localization of the glutamate transporter protein GLAST in rat retina. Brain Res. 744, 129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pow D. V., Barnett N. L. (1999) Changing patterns of spatial buffering of glutamate in developing rat retinae are mediated by the Muller cell glutamate transporter GLAST. Cell Tissue Res. 297, 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kugler P., Beyer A. (2003) Expression of glutamate transporters in human and rat retina and rat optic nerve. Histochem. Cell Biol. 120, 199–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fyk-Kolodziej B., Qin P., Dzhagaryan A., Pourcho R. G. (2004) Differential cellular and subcellular distribution of glutamate transporters in the cat retina. Vis. Neurosci. 21, 551–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rauen T., Wiessner M., Sullivan R., Lee A., Pow D. V. (2004) A new GLT1 splice variant: cloning and immunolocalization of GLT1c in the mammalian retina and brain. Neurochem. Int. 45, 1095–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schultz K., Stell W. K. (1996) Immunocytochemical localization of the high-affinity glutamate transporter, EAAC1, in the retina of representative vertebrate species. Neurosci. Lett. 211, 191–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiessner M., Fletcher E. L., Fischer F., Rauen T. (2002) Localization and possible function of the glutamate transporter, EAAC1, in the rat retina. Cell Tissue Res. 310, 31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coco S., Verderio C., Trotti D., Rothstein J. D., Volterra A., Matteoli M. (1997) Non-synaptic localization of the glutamate transporter EAAC1 in cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J. Neurosci. 9, 1902–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ward M. M., Jobling A. I., Puthussery T., Foster L. E., Fletcher E. L. (2004) Localization and expression of the glutamate transporter, excitatory amino acid transporter 4, within astrocytes of the rat retina. Cell Tissue Res. 315, 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mäenpää H., Gegelashvili G., Tähti H. (2004) Expression of glutamate transporter subtypes in cultured retinal pigment epithelial and retinoblastoma cells. Curr. Eye Res. 28, 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mim C., Balani P., Rauen T., Grewer C. (2005) The glutamate transporter subtypes EAAT4 and EAATs 1–3 transport glutamate with dramatically different kinetics and voltage dependence but share a common uptake mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 126, 571–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arriza J. L., Eliasof S., Kavanaugh M. P., Amara S. G. (1997) Excitatory amino acid transporter 5, a retinal glutamate transporter coupled to a chloride conductance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4155–4160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gameiro A., Braams S., Rauen T., Grewer C. (2011) The discovery of slowness: low-capacity transport and slow anion channel gating by the glutamate transporter EAAT5. Biophys. J. 100, 2623–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eliasof S., Arriza J. L., Leighton B. H., Kavanaugh M. P., Amara S. G. (1998) Excitatory amino acid transporters of the salamander retina: identification, localization, and function. J. Neurosci. 18, 698–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pow D. V., Barnett N. L. (2000) Developmental expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 5: a photoreceptor and bipolar cell glutamate transporter in rat retina. Neurosci. Lett. 280, 21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pow D. V., Barnett N. L., Penfold P. (2000) Are neuronal transporters relevant in retinal glutamate homeostasis? Neurochem. Int. 37, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Palmer M. J., Taschenberger H., Hull C., Tremere L., von Gersdorff H. (2003) Synaptic activation of presynaptic glutamate transporter currents in nerve terminals. J. Neurosci. 23, 4831–4841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wersinger E., Schwab Y., Sahel J. A., Rendon A., Pow D. V., Picaud S., Roux M. J. (2006) The glutamate transporter EAAT5 works as a presynaptic receptor in mouse rod bipolar cells. J. Physiol. 577, 221–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Picaud S., Larsson H. P., Wellis D. P., Lecar H., Werblin F. (1995) Cone photoreceptors respond to their own glutamate release in the tiger salamander. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9417–9421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Melzer N., Biela A., Fahlke Ch. (2003) Glutamate modifies ion conduction and voltage-dependent gating of excitatory amino acid transporter-associated anion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50112–50119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hebeisen S., Fahlke Ch. (2005) Carboxy-terminal truncations modify the outer pore vestibule of muscle chloride channels. Biophys. J. 89, 1710–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sigworth F. J., Zhou J. (1992) Ion channels. Analysis of nonstationary single-channel currents. Methods Enzymol. 207, 746–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Efron B., Tibshirani R. (1993) An Introduction to the Bootstrap., Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 29. Janssen A. G., Scholl U., Domeyer C., Nothmann D., Leinenweber A., Fahlke Ch. (2009) Disease-causing dysfunctions of barttin in Bartter syndrome type IV. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 145–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leinenweber A., Machtens J. P., Begemann B., Fahlke Ch. (2011) Regulation of glial glutamate transporters by C-terminal domains. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1927–1937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alekov A., Fahlke Ch. (2009) Channel-like slippage modes in the human anion/proton exchanger ClC-4. J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 485–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bergles D. E., Tzingounis A. V., Jahr C. E. (2002) Comparison of coupled and uncoupled currents during glutamate uptake by GLT-1 transporters. J. Neurosci. 22, 10153–10162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fairman W. A., Vandenberg R. J., Arriza J. L., Kavanaugh M. P., Amara S. G. (1995) An excitatory amino-acid transporter with properties of a ligand-gated chloride channel. Nature 375, 599–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wadiche J. I., Amara S. G., Kavanaugh M. P. (1995) Ion fluxes associated with excitatory amino acid transport. Neuron 15, 721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wadiche J. I., Kavanaugh M. P. (1998) Macroscopic and microscopic properties of a cloned glutamate transporter/chloride channel. J. Neurosci. 18, 7650–7661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larsson H. P., Picaud S. A., Werblin F. S., Lecar H. (1996) Noise analysis of the glutamate-activated current in photoreceptors. Biophys. J. 70, 733–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Torres-Salazar D., Fahlke Ch. (2007) Neuronal glutamate transporters vary in substrate transport rate but not in unitary anion channel conductance. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34719–34726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Winter N., Kovermann P., Fahlke Ch. (2012) A point mutation associated with episodic ataxia 6 increases glutamate transporter anion currents. Brain 135, 3416–3425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Melzer N., Torres-Salazar D., Fahlke Ch. (2005) A dynamic switch between inhibitory and excitatory currents in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19214–19218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kovermann P., Machtens J. P., Ewers D., Fahlke Ch. (2010) A conserved aspartate determines pore properties of anion channels associated with excitatory amino acid transporter 4 (EAAT4). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23676–23686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hille B. (2002) Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd Ed., Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lasansky A. (1981) Synaptic action mediating cone responses to annular illumination in the retina of the larval tiger salamander. J. Physiol. 310, 205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rabl K., Bryson E. J., Thoreson W. B. (2003) Activation of glutamate transporters in rods inhibits presynaptic calcium currents. Vis. Neurosci. 20, 557–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duebel J., Haverkamp S., Schleich W., Feng G., Augustine G. J., Kuner T., Euler T. (2006) Two-photon imaging reveals somatodendritic chloride gradient in retinal ON-type bipolar cells expressing the biosensor Clomeleon. Neuron 49, 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hotzy J., Schneider N., Kovermann P., Fahlke Ch. (2013) Mutating a conserved proline residue within the trimerization domain modifies Na+ binding to EAAT glutamate transporters and associated conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36492–36501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]