Abstract

The m-TOR inhibitor sirolimus is an immunosuppressive drug used in kidney transplantation. m-TOR binds with Raptor and phosphorylates p70S6 kinase, a protein involved in numerous cell signalling pathways. We investigated the association of candidate polymorphisms in m-TOR, Raptor and p70S6K, sirolimus dose and exposure, and other time-independent as well as time-dependent covariates, with sirolimus-induced adverse events in kidney transplant recipients. This study included a first group of 113 patients, switched from a calcineurin inhibitor to sirolimus and a validation group of 66 patients from another clinical trial, with the same immunosuppressive regimen. The effects of gene polymorphisms and covariates on total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, hemoglobin, cutaneous adverse events, oedemas and infections were studied using multilinear regression, or logistic regression imbedded in linear mixed-effect models. An m-TOR variant haplotype was significantly associated with a decrease in hemoglobin levels in the two populations of patients (discovery group: β=−0.82 g/dl, p=0.0076; validation group: β=−1.58 g/dl, p=0.0308). Increased sirolimus trough levels were significantly associated with increased total cholesterol levels (discovery group: β =0.02 g/l, p<0.0001, validation group: β =0.02 g/l, p=0.0002) and triglyceride levels (discovery group: β =0.02 g/l, p=0.0059, validation group: β =0.05 g/l, p=0.0370). Sirolimus trough levels were also associated with an increased risk for cutaneous adverse events (OR=1.97, 95%CI [1.32–1.94], p=0.0009) and oedemas (OR=1.16, 95%CI [1.03–1.30], p=0.01342) in the discovery group, but this was not confirmed in the validation group. These results provide evidence of an association between an m-TOR haplotype and a decrease in hemoglobin in renal transplant recipients.

Keywords: Adaptor Proteins, Signal Transducing; genetics; Adult; Aged; Female; Follow-Up Studies; Graft Rejection; Haplotypes; Humans; Immunosuppressive Agents; adverse effects; Kidney; drug effects; metabolism; Kidney Transplantation; Logistic Models; Longitudinal Studies; Male; Middle Aged; Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinases, 70-kDa; genetics; Sirolimus; adverse effects; TOR Serine-Threonine Kinases; genetics

Keywords: sirolimus, adverse event, mammalian target of rapamycin, p70S6 kinase, raptor, pharmacogenetics.

Introduction

Sirolimus (SRL) is an immunosuppressive drug used in solid organ transplantation. Its use is restricted because of adverse effects [1], the most frequent of which are anemia, cutaneous lesions (cutaneous AEs), oedemas and dyslipemia [2–4]. Pneumonitis is very rare but could be fatal [5]. SRL binds to the FK506 binding protein (FKBP12) and this binary complex inhibits the mammalian target of Rapamycin (m-TOR), a protein kinase. The m-TOR protein is included in two complexes, m-TORC1 and m-TORC2, of which only the former is sensitive to SRL [6]. m-TORC1 contains 3 proteins: m-TOR, a G protein beta-subunit-like protein and the Regulatory Associated Protein of m-TOR (Raptor). Inhibition of m-TORC1 by SRL modulates cell growth and proliferation, as well as metabolic homeostasis [7] through the phosphorylation and inhibition of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein (4E-BP1) and the phosphorylation and activation of the p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) [8, 9]. Given the major role of m-TORC1 in many different metabolic pathways, its inhibition might contribute to SRL AEs. In particular, lipid disorders might be directly linked to the m-TOR downstream signaling pathway, as it integrates inputs from multiple origins including nutrients, energy and insulin [10]. Sirolimus induced lymphoedemas seem to be linked to the impairment of VEGF-A downstream signal through the inhibition of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway by sirolimus [11]. Most of these adverse effects develop with time during maintenance treatment with SRL. Consequently, the study of such effects requires investigating the combined effects of the drug exposure level, duration and dose. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the association of genetic polymorphisms in proteins of the mTOR pathway and SRL effects in transplant patients with a longitudinal follow-up.

The gene encoding m-TOR (MTOR) is located on chromosome 1p36 and contains 58 exons. Thirty five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been described in this gene (data from the Hapmap project, www.hapmap.org, version 3, release 27, panel CEU), with strong linkage disequilibrium. Five of these SNPs (Tag SNPs) give rise to six MTOR haplotypes. The gene encoding p70S6K (RPB6KB1) is located on chromosome 17q23.1 and is made up of 15 exons. Seventeen SNPs have been described for this gene, with 5 tag SNPs able to discriminate 5 different alleles. The gene encoding Raptor (RPTOR) is located on chromosome 17q25 and has a more complex structure, with 25 blocks containing 237 SNPs. A Raptor SNP affecting signal transduction has recently been described [12] and 3 SNPs have been associated with the risk of bladder cancer [13].

The objective of this work was to study in kidney transplant recipients with a longitudinal follow-up the association of m-TOR, Raptor and p70S6K polymorphisms, sirolimus dose and exposure, demographics, laboratory tests and other treatment covariates on the one hand, with lipid plasma levels, hemoglobin (Hb), cutaneous AEs, oedemas and infections on the other.

Methods

Data were collected from patients who participated in two trials. Both studies complied with the declaration of Helsinki and were approved by ethics committees. A written informed consent was obtained from each patient enrolled. The influence of MTOR, RPS6KB1 and RPTOR polymorphisms, individual laboratory test results and SRL exposure and dose was first investigated in patients included in the “discovery study”. The “validation study” intended to test the replication of the first study findings in a different population of patients.

Discovery study: patients and data

Between October 2000 and December 2008, 180 kidney-transplant patients were switched from a calcineurin inhibitor to sirolimus at least 3 months after transplantation. Among these patients, all those who later attended our outpatient clinic and who gave their informed consent were included in the study, whether they were still receiving SRL or not (n=113). A blood sample was drawn from each patient for genetic analyses. All patients included in the study were aged > 18 years, had a functioning graft, and had received sirolimus for at least 3 months. None of the patients had sirolimus stopped within the first 6 months post-conversion for uncontrolled adverse events. For each patient, the following clinical data were recorded: date of graft and date of SRL introduction, age, gender, initial nephropathy, time on dialysis before transplantation, number of kidney transplantation procedures, presence and date of occurrence of cutaneous AEs, lymphoedemas, and infections. Infections were defined as severe infections, respiratory or not, requiring hospitalization. Cutaneous AEs were defined as cutaneous lesions, folliculites, aphthous stomatitis, macula-papular and squamous lesions, and acne. Oedemas were also collected from the clinical files. Additionally the doses of all immunosuppressants including steroids (if any), serum creatinine level, leukocyte count, Hb, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), total cholesterol (tCHL), low-density – lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TRG) plasma levels and the dose and type of statins were retrospectively collected from patient charts at several periods: three months before the switch, on SRL introduction, and then 1, 3 and 6 months after the switch to sirolimus. Dyslipemia and anemia were studied as continuous variables, using the tCHL, TRG, LDL-C plasma levels and Hb blood level. Statins administration was categorized in 4 strata: no statin (statins=0), low dose of statins (statins=1; 10 mg/day of pravastatin, simvastatin or atorvastatin), middle dose of statins (statins=2; 20 or 30 mg/day of pravastatin and 20 to 40 mg/day of simvastatin or atorvastatin) and high dose (statins=3; 40 mg/day of pravastatin and 50 to 80 mg/day of simvastatin or atorvastatin). Pneumonitis was not studied because only 4 cases were reported in this study.

Validation study: patients and data

The second group consisted of 66 patients treated by SRL and MMF and included in CONCEPT, an open-label, randomized, multicenter trial conducted in 16 French centres between November 2004 and October 2006 (Eudract-N° 2004-002987-62). Inclusion criteria, basal immunosuppressant therapy and the results of the main study were described elsewhere [14].

Patients were treated with MMF and cyclosporine A (CsA) from day 0 to week 12 and then randomized at week 12 between: continuation on CsA (patient group not studied in this work); or switch to SRL, with a loading dose of 10 mg/day for 2 consecutive days followed by 6 mg daily, adjusted to maintain C0 blood levels between 8 ng/mL and 15 ng/mL from week 12 to week 39, then between 5 ng/mL and 10 ng/mL after week 39. Oral steroids were planned to be discontinued 8 months post-transplantation. All patients had SRL C0 measurements made at weeks 13, 14, 16, 26, 39 and 52. LDL and HDL cholesterol, TRG and hemoglobin levels and body weight were noted at each visit, before (day 0 and weeks 4, 8 and 12 post-transplantation) and after SRL introduction (weeks 13, 14, 16 to 26, 39 and 52). Cutaneous AEs (including aphthous stomatitis, folliculitis and acne), oedema and infections were collected from patients’ clinical research files.

SNP selection and identification of genotypes

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-treated blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAGEN S.A., Courtaboeuf, France). Tagging SNPs were selected using the Haploview tagger algorithm [15], (version 2, release 24, panel CEU), with a cut-off of 0.80 for r2 and a minimum minor allele frequency more than 0.01, based on data from samples genotyped by the Hapmap project (www.hapmap.org) [16]. A total of 5 SNPs in MTOR (rs1770345, rs2300095, rs2076655, rs1883965 and rs12732063), 5 SNPs in RPS6KB1 (rs8071475, rs2526354, rs1292034, rs180535, rs8067568) were selected to represent the genetic variations of MTOR (35 tagged SNPs) and RPS6KB1 (17 tagged SNPs). Four RPTOR SNPs (rs2289759, rs7212142, rs7211818, rs11653499) were selected based on the literature [12, 13]. Genotypes were characterized using TaqMan Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction discrimination assay (ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System; Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Assays were ordered from Applied-Biosystems as functionally tested assays (references C__15753976_10, C__15866804_10, C__2562807_10, C__26761742_10, C___347870_10, C__2562791_10, C__43730643_10, C__15882533_10, C_11647372, C__441451_20, C__1971406_10, C___1971465_10, C__29221695_10, C__135233_10).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using R software version 2.10.1 (R foundation for statistical computing, http://www.r-project.org). Deviations from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were assessed using the Hardy-Weinberg exact test with the package “SNPassoc”. Linear mixed effect models were fitted using the “lme4” package. Four continuous phenotypes (tCHL, TRG, LDL-C and Hb levels) and 3 binary phenotypes (infection, oedema, cutaneous adverse events) were studied using data collected before SRL introduction, at the time of SRL introduction and at different time-points post-introduction, as described above. Random effects were included on both the baseline value (before SRL introduction; intercept) and the different following visits (slope). Time independent covariates (age at the inclusion, gender, time post grafting and m-TOR, p70S6K and Raptor SNPs or haplotypes), as well as covariates measured over time (steroid administration (yes/no), steroid dose, SRL dose, SRL trough concentration, and statins (in model including dyslipemia) or EPO prescription/blood transfusion (in model including Hb)) were studied as follows. In a first step, each covariate was tested as a fixed effect in univariate analysis. In the second step, all the significant covariates with p<0.2 in the univariate analysis were included simultaneously in an intermediate multivariate model, and then each covariate was removed from the intermediate model to confirm its relevance using the likelihood ratio test (backward deletion strategy).

For association analyses of SNPs and haplotypes, the most frequent allele was considered as the reference. A dominant genetic model was chosen when the frequency of homozygotes for the ancestral allele (as reported in the NCBI database) was less than 5% and a recessive genetic model when the frequency of homozygotes for the variant allele was less than 5%. In the other situations, an additive model of inheritance was chosen.

After SNP association analysis, the p70S6K, Raptor and m-TOR haplotypes were investigated using the “haplo.stat” package and the haplotype frequencies in our population were compared to the Hapmap frequencies using the Chi-square test.

Haplotype analysis was performed using linear regression and a log-additive genetic model for each of the visits studied in the discovery population (3 months before, on SRL introduction, and then 1, 3 and 6 months after). A haplotype significantly associated with a given AE at more than 2 visits was considered to be potentially at risk and was included in the multivariate analysis as a three categorical dummy variable (i.e. homozygous carriers, heterozygous carriers or non-carriers). The normality of continuous phenotype distribution (tCHL, LDL-C, TRG and Hb) was assessed by both visual examination of the probability density function and by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Classically, the linearity of continuous parameters was studied by comparing a nested quadratic model (a+ β1x1+ β 2x1 2) and a linear model (a+ β1x1) by likelihood ratio tests. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical data

Patient characteristics at the time of the switch from a calcineurin inhibitor to sirolimus are described in Table 1 (time-independent covariates), Table 2 and in supplemental digital content (Table S1) (time-related covariates). For some patients, covariate values were missing completely at random. A high rate of missing LDL-C levels was observed in the discovery group, which is presumably because this analysis is less routinely performed as compared to total CHL or TRG. No significant deviation from normality was found for tCHL TRG, LDL-C or Hb level distributions. Significant deviation from linearity was observed for: the time post-SRL introduction in the models investigating cutaneous AEs, oedemas, Hb and TRG levels; and for SRL trough levels in the model investigating the cutaneous AEs. Consequently, a quadratic model was used for these analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the kidney transplant patients enrolled in the studies at the time of switch to sirolimus

| Covariates | Discovery study | Validation study |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| mean±sd | 52±14 years | 47±12 years |

| n | 113 | 66 |

|

| ||

| Time between transplantation and conversion to sirolimus | ||

| mean±sd | 5.9±5.9 years | 90.8±8 days |

| min-max | 0.3–25.9 | 77–116 |

| n | 113 | 66 |

|

| ||

| Sex ratio | ||

| Male/Female | 80/33 | 46/20 |

|

| ||

| Rank of kidney transplantation | ||

| -1: n (%) | 102 (90%) | 66 (100%) |

| -2: n (%) | 10 (9%) | |

| -3: n (%) | 1 (1%) | |

|

| ||

| Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) given before SRL | ||

| Cyclosporine A | ||

| n (%) | 73 (65%) | 66 (100%) |

| daily dose (mean ±sd) | 178±58 mg | |

| Tacrolimus | ||

| n (%) | 40 (35%) | |

| daily dose (mean ±sd) | 3.8±2.0 mg | |

Variables normally distributed are expressed as mean±sd and those not normally distributed as median (range).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the discovery population for time-related data, 3 months before (M-3), at the time of sirolimus (SRL) introduction (M0), and 1, 3 and 6 months (M1, M3, M6)* after.

| M−3 | M0 | M1 | M3 | M6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tCHL (g/L) | |||||

| n (available) | 94 | 101 | 99 | 93 | 90 |

| mean±sd | 1.87±0.40 | 1.81±0.40 | 2.05±0.43 | 2.15±0.48 | 2.07±0.41 |

| min-max | 0.80–3.52 | 0.86–2.75 | 1.10–3.49 | 0.98–3.57 | 1.03–2.83 |

|

| |||||

| LDL-C (g/L) | |||||

| n (available) | 68 | 59 | 61 | 69 | 73 |

| mean±sd | 0.99±0.31 | 0.88±0.36 | 1.06±0.40 | 1.19±0.44 | 1.15±0.40 |

| min-max | 0.34–1.72 | 0.18–1.94 | 0.25–2.03 | 0.22–2.17 | 0.15–2.00 |

|

| |||||

| TRG (g/L) | |||||

| n (available) | 93 | 101 | 100 | 94 | 89 |

| mean±sd | 1.45±0.77 | 1.58±0.96 | 1.87±0.921.05 | 1.98±0.88 | 1.93±1.07 |

| min-max | 0.50–4.91 | 0.41–6.38 | 0.46–4.53 | 0.53–4.79 | 0.41–7.46 |

|

| |||||

| Statins dose group | |||||

| 0 n (%) | 50 (44.2) | 47 (41.6) | 42 (37.2) | 41 (36.3) | 37 (32.7) |

| 1 n (%) | 31 (27.4) | 27 (23.9) | 30 (26.6) | 32 (28.3) | 34 (30.1) |

| 2 n (%) | 23 (20.3) | 27 (23.9) | 25 (22.1) | 23 (20.3) | 23 (20.3) |

| 3 n (%) | 9 (8.0) | 12 (10.6) | 16 (14.1) | 17 (15.1) | 19 (16.8) |

|

| |||||

| SRL trough level (ng/mL) | |||||

| n (available) | NA | NA | 106 | 97 | 98 |

| mean±sd | 10.5±3.9 | 9.8±4.3 | 9.8±3.7 | ||

|

| |||||

| SRL dose (mg) | |||||

| n (available) | NA | NA | 110 | 101 | 96 |

| mean±sd | 3.0±1.2 | 3.0±1.2 | 3.0±1.3 | ||

|

| |||||

| Steroids | |||||

| yes/no | 90/19 | 94/19 | 97/16 | 86/14 | 87/10 |

| mean dose±sd (mg) | 7.9±4.4 | 7.9±5.1 | 7.5±4.2 | 7.5±5.3 | 6.2±3.0 |

| min-max | 1–20 | 1.25–30 | 1–30 | 2–40 | 2–20 |

|

| |||||

| Mycophenolic acid | |||||

| yes/no | 83/26 | 83/30 | 84/29 | 74/27 | 72/25 |

| mean dose±sd (mg) | 1524±539 | 1454±464 | 1394±477 | 1266±435 | 1221±391 |

| min-max | 500–3000 | 500–2000 | 500–3000 | 500–2000 | 500–2000 |

|

| |||||

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | |||||

| n (available) | 106 | 112 | 110 | 97 | 97 |

| mean±sd | 156±100 | 161±97 | 136±38 | 141±42 | 139±42 |

|

| |||||

| Leukocyte (G/L) | |||||

| n (available) | 103 | 106 | 107 | 77 | 74 |

| mean ±sd | 7.1±2.4 | 7.1±2.8 | 5.6±2.2 | 6.0±2.2 | 6.2±2.3 |

|

| |||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||||

| n (available) | 105 | 106 | 108 | 78 | 76 |

| mean±sd | 12.9±1.7 | 12.9±1.5 | 12.4±1.3 | 12.3±1.3 | 12.8±1.3 |

|

| |||||

| Mean Corpuscular volume (fl) | |||||

| n (available) | 96 | 102 | 103 | 76 | 72 |

| mean±sd | 90.7±5.6 | 90.7±4.5 | 88.4±4.8 | 85.7±5.1 | 82.4±4.4 |

|

| |||||

| Infection | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 25 (22%) |

|

| |||||

| Cutaneous AEs | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 26 (23%) | 7 (6%) | 8 (7%) |

|

| |||||

| Oedema | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 7 (6%) | 11 (10%) |

the number of patients was different between visits due to missing values totally at random. tCHL is total cholesterol, LDL-C is low density lipoprotein cholesterol, TRG is triglycerides. Statins dose group: ‘0’: no statins, ‘1’ low dose of statins (10 mg of pravastatin, simvastatin or atorvastatin), ‘2’: middle dose of statins (20 or 30 mg of pravastatin and 20 to 40 mg of simvastatin or atorvastatin) and ‘3’: high dose (40 mg of pravastatin and 50 to 80 mg of simvastatin or atorvastatin).

Genotype/haplotype distribution

Genotyping results were in the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and similar to those reported in Hapmap.

The p70S6K rs2526354, rs180535, rs8067568 and m-TOR rs12732063 SNPs were studied using a dominant genetic model. Raptor rs2289759 and rs7211818 were studied using a recessive genetic model. All other SNPs were studied using an additive model. The m-TOR, Raptor and p70S6K haplotype frequencies found in our population were similar to those reported in Hapmap (See supplemental digital content: Table S2).

Multivariate association analysis of pharmacogenetics and clinical covariates with SRL AEs (Table 3)

Table 3.

Multivariate Linear Mixed Effects Regression analyses for total cholesterol (tCHL), triglyceride(TRG) low-density-lipoprotein plasma-cholesterol (LDL-C), hemoglobin, infections, cutaneous adverse events and oedemea in the discovery study and in the validation study, using final discovery study models.

| Discovery study | Validation study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Category | Adjusted β coefficient | Adjusted s.e. | Adjusted p | Adjusted β coefficient | Adjusted s.e. | Adjusted p |

| Multivariate analysis tCHL | |||||||

| Intercept | 1.710 | 0.071 | <0.0001 | 1.441 | 0.215 | <0.0001 | |

| Time post-SRL introduction | Per inter-visit delay | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.5768 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.0791 |

| Statin group | 1 vs 0 2 vs 0 3 vs 0 |

0.030 0.040 0.154 |

0.057 0.062 0.075 |

0.5124 0.3156 0.0358 |

Non available | Non available | Non available |

| SRL trough level | Per 1 ng/ml increase | 0.017 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | 0.021 | 0.006 | <0.0001 |

| Steroids | Yes vs No | 0.152 | 0.068 | 0.0249 | 0.547 | 0.126 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariate analysis TRG | |||||||

| Intercept | 1.599 | 0.080 | <0.0001 | 0.630 | 1.055 | 0.5510 | |

| Time post-SRL introduction | 0.050 | 0.019 | 0.0111 | 0.083 | 0.061 | 0.1650 | |

| Î(Time post-SRL introduction2) | −0.005 | 0.003 | 0.1399 | −0.001 | 0.0008 | 0.1250 | |

| SRL trough level | Per 1 ng/ml increase | 0.020 | 0.007 | 0.0059 | 0.047 | 0.023 | 0.0370 |

| Multivariate analysis LDL-C | |||||||

| Intercept | 0.847 | 0.066 | <0.0001 | 1.372 | 0.115 | <0.0001 | |

| Time post-SRL introduction | Per inter-visit delay | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.6003 | −0.007 | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | M vs F | 0.136 | 0.065 | 0.0388 | 0.107 | 0.088 | 0.2259 |

| SRL trough level | Per 1 ng/ml increase | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.0058 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.2236 |

| Statin group | 1 vs 0 2 vs 0 3 vs 0 |

−0.012 0.041 0.146 |

0.058 0.067 0.074 |

0.9999 0.5183 0.0455 |

Non available | Non available | Non available |

| Multivariate analysis hemoglobin | |||||||

| Intercept | 12.88 | 0.129 | <0.0001 | 13.10 | 0.488 | <0.0001 | |

| Time post-SRL introduction | Per inter-visit delay | −0.032 | 0.033 | 0.3371 | −0.056 | 0.029 | 0.0270 |

| Î(Time post-SRL introduction2) | Per inter-visit delay | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.0358 | 0.001 | 0.0005 | 0.0281 |

| Haplotype | rs1770345 A/ rs2300095 G/ rs2076655 A/ rs1883965 A/ rs12732063 A vs other |

−0.819 | 0.306 | 0.0076 | −1.557 | 0.732 | 0.0308 |

| SRL trough level | Per 1 ng/ml increase | −0.032 | 0.014 | 0.0203 | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.0010 |

| Delay transplantation/SRL introduction | Per year increase | 0.035 | 0.015 | 0.0188 | Non available | Non available | Non available |

| EPO or blood transfusion | Yes vs No | 0.172 | 0.283 | 0.5420 | −0.060 | 0.691 | 0.9500 |

| Covariates | Category | Adjusted OR | Adjusted 95CI | Adjusted p | Adjusted OR | Adjusted 95CI | Adjusted p |

| Multivariate analysis Infection | |||||||

| Time post-SRL introduction | Per inter-visit delay | 1.82 | 1.48–2.23 | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.4960 |

| Multivariate analysis Cutaneous adverse event | |||||||

| Time post-SRL introduction | Per inter-visit delay | 0.79 | 0.48–1.29 | 0.3491 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.2750 |

| Î(Time post-SRL introduction2) | Per inter-visit delay | 0.99 | 0.92–1.07 | 0.8832 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.8190 |

| SRL trough level | Per 1 ng/ml increase | 1.97 | 1.32–2.94 | 0.0009 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.2680 |

| I(SRL trough level2) | Per 1 ng/ml increase | 0.98 | 0.96–0.99 | 0.0007 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.2020 |

| Multivariate analysis oedema | |||||||

| Time post-SRL introduction | Per inter-visit delay | 4.73 | 1.02–21.90 | 0.0466 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.0859 |

| Î(Time post-SRL introduction2) | Per inter-visit delay | 0.85 | 0.70–1.03 | 0.0913 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.0605 |

| Age | Per year increase | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | 0.0022 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.3680 |

| SRL trough level | Per 1 ng/ml increase | 1.16 | 1.03–1.30 | 0.0134 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.8584 |

There was no statistical interaction between covariates; SRL is sirolimus; β is the estimate of the regression coefficient and s.e. its standard error, OR is the Odd Ratio and 95CI the 95% confidence interval of the OR. Statins dose group: 0 no statins, ‘1’: low dose of statins (10 mg of pravastatin, simvastatin or atorvastatin), ‘2’: middle dose of statins (20 or 30 mg of pravastatin and 20 to 40 mg of simvastatin or atorvastatin) and ‘3’: high dose of statins (40 mg of pravastatin and 50 to 80 mg of simvastatin or atorvastatin). CHL, TRG and LDL-C are in g/L, Hb is in g/dL.

Pharmacogenetics

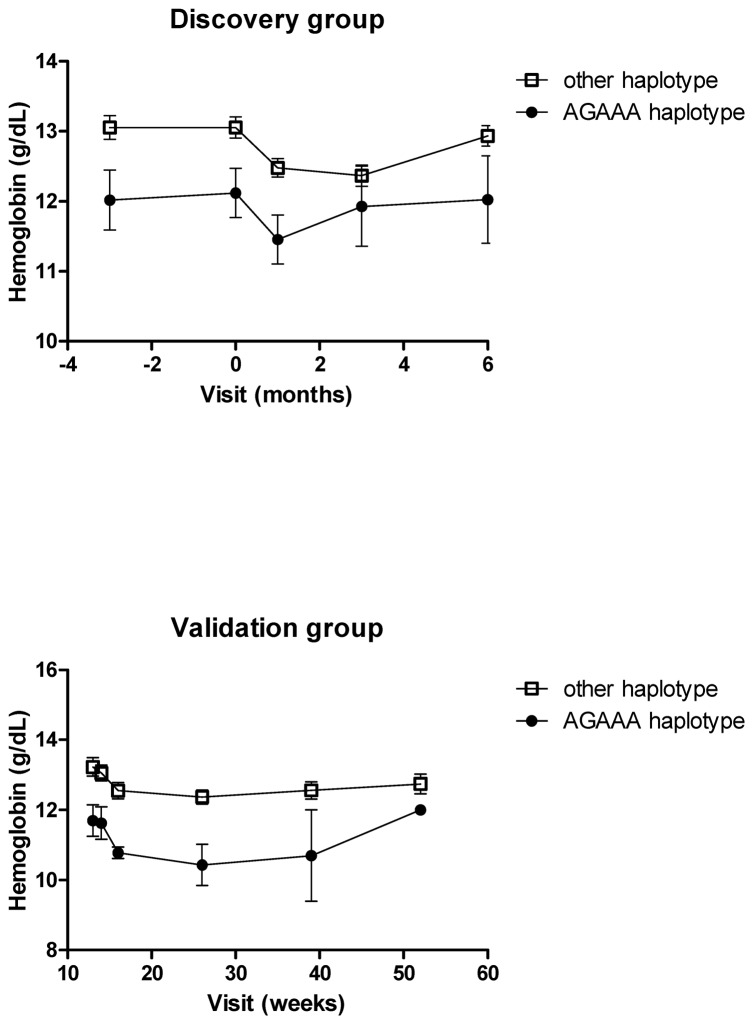

In the final multivariate model obtained in the discovery group adjusted on time post-SRL introduction and EPO prescription, the following factors were significantly associated with a decrease of Hb level: (i) SRL trough levels (p=0.0203); (ii) the time between transplantation and SRL introduction (p=0.0188); and (iii) m-TOR AGAAA haplotype (rs1770345/rs2300095/rs2076655/rs1883965/rs12732063) (p=0.0076) occurring at a frequency of 0.055. Moreover, the decrease of Hb level was associated with a decrease of the MCV, characterizing a microcytosis (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the difference in Hb levels between the two haplotype groups over the follow-up period. No association was found between Hb levels and m-TOR, p70S6K or Raptor polymorphisms studied as SNPs. In the validation study, the m-TOR AGAAA haplotype (p=0.0308) and the time post-SRL introduction (p=0.0270) were also significantly associated with a decrease in Hb levels (Figure 1). Contrary to what was observed in the discovery study, SRL trough levels were associated with increased Hb levels.

Figure 1.

Evolution of the hemoglobin level according to m-TOR haplotype AGAAA (rs1770345/rs2300095/rs2076655/rs1883965/rs12732063) vs others over the follow-up periods in the discovery and in the validation groups.

No association was found between tCHL, TRG, LDL, infection, cutaneous AEs and oedema and m-TOR, p70S6K or Raptor polymorphisms, whether studied as SNPs or haplotypes.

Non genetic factor and AEs

In the discovery population, multivariate linear regression adjusted on the time post-SRL introduction, statin dose strata and steroid administration, showed that SRL trough levels were significantly and positively associated with tCHL (p<0.0001), TRG (p=0.006) and LDL (p=0.006) levels. This effect of increased tCHL (p<0.0001) and TRG (p=0.0370) levels with increased SRL trough levels was confirmed in the validation population.

Logistic regression adjusted on the time post-SRL introduction in the discovery population showed that SRL trough levels were associated with oedemas (p=0.0134) in addition of patient age at the time of SRL introduction (p=0.0022), as well as with cutaneous AEs (p=0.0009). However, such associations were not found in the validation population.

Discussion

We found a significant association between an m-TOR variant haplotype and decreased Hb levels in renal transplant patients on sirolimus and confirmed the previously published relationships between SRL trough levels and dyslipemia [17], cutaneous AEs [3], oedemas [11] and decreased Hb levels [2].

We used a longitudinal design and mixed effect modeling, particularly appropriate to model the impact of time-dependent drug exposure, together with demographic, clinical, biological and genetic covariates on the occurrence of adverse effects.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first association study between m-TOR, p70S6K and Raptor gene polymorphisms, sirolimus administration and sirolimus adverse events in kidney transplant patients with a longitudinal follow-up. The polymorphisms and haplotypes studied, based on those reported during the Hapmap project, were representative of the whole m-TOR and p70S6K genes, and those chosen for Raptor had previously been associated with bladder cancer or with changes in Raptor activity in vitro [12, 13].

We found that the AGAAA (rs1770345/rs2300095/rs2076655/rs1883965/rs12732063) m-TOR haplotype (frequency=0.055), in addition to SRL trough levels, was strongly associated with decreased Hb levels. The effect of this haplotype was confirmed in an independent group of patients, contrary to that of SRL through levels, which were inversely associated with Hb levels in the validation group. We have no explanation for this discrepancy. It is noteworthy that the effect of the haplotype was statistically independent of EPO prescription/blood transfusion because no effect of this factor or interaction with the haplotype effect was found. It has been shown that the inhibition of m-TOR by SRL leads to a diminution of erythroïd cell lines proliferation in vitro [18]. A hypothesis proposed by Fishbane is that SRL could result in early differentiation of erythroid precursors and diminished globin synthesis, leading to microcytic anemia [19]. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed that patients treated by SRL experienced a concentration-dependent microcytosis. A possible mechanism could be that carriers of the AGAAA m-TOR haplotype have a basal decrease in m-TOR activity and/or level, associated with an early differentiation of erythroid precursors and that the introduction of sirolimus leads to a higher decrease of Hb in the AGAAA group compared to the other groups. In this case, this haplotype could also possibly be associated with an increased SRL treatment efficacy through decreased mTOR activity, but we have no data yet to support this hypothesis.

We found no association between m-TOR, p70S6K or Raptor genetic polymorphisms and lipid levels but we confirmed the previously reported [17, 20] proportionality between sirolimus trough levels and tCHL, LDL-C and TRG plasma levels. Only one study had previously quantified this relationship using a longitudinal follow-up in 280 renal transplants treated de novo by SRL, CsA and prednisolone [20]. The authors concluded that dyslipemia (hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia) was associated with SRL through levels, but not dose [20], a finding we confirmed here in two independent groups of patients. In the discovery population, the patients with the highest levels of tCHL or LDL-C received the highest statin doses, the latter being probably a consequence of the former. We also found the well-known increase in tCHL cholesterol associated with corticosteroids in the discovery and in the validation groups, and the previously reported difference in LDL-C level between men and women [21] in the discovery group only.

Other associations with SRL AEs were also found only in the discovery group but again, m-TOR, p70S6K or Raptor genetic polymorphisms were not contributory. (i) The time post-SRL introduction was the only factor associated with infections. The occurrence of infections is indeed more likely to be influenced by a combination of the overall immunosuppressive effect (rather than specifically that of SRL) and of the probably of encountering infectious microorganisms (hence time). (ii) Cutaneous adverse events were strongly associated with SRL trough levels. This association is well known in clinical practice. (iii) SRL trough levels, age and time post-SRL introduction were significantly associated with oedema. It was previously hypothesized that SRL may lead to a reduction of VEGF production and/or to the inhibition of the growth of vascular smooth-muscle cells, which would secondarily trigger oedemas [3]. We could confirm here the concentration-related nature of this AE, consistent with the usual SRL dose decrement in the case of oedemas.

There were thus a number of differences between the results of the discovery and the validation studies regarding cutaneous AEs and oedemas. There are several possible explanations for these differences. First, the design of the discovery study was specifically focused on SRL AEs which led to an exhaustive screening of patient files. In contrast, the patients of the validation group had been enrolled in a randomized clinical trial with a different principal objective (study of renal function), which presumably resulted in a difference in AEs reporting and with close therapeutic drug monitoring of SRL. Secondly, there were twice as many patients in the discovery than in the validation study.

Our hypothesis was that individual or combinations of polymorphisms in the major genes of SRL pharmacodynamic pathway could influence patients’ sensitivity to SRL and thus their likelihood to experience adverse events, independently of SRL levels, treatment duration and other confounding factors (e.g. steroids, statins or EPO administration…). We thus performed a stepwise multivariate procedure which allowed us to investigate the additional value of a given gene polymorphism by adjusting the model on other polymorphisms or non-genetic factors. Although a stepwise procedure decreases the number of tests performed as compared to univariate testing of each variable on each phenotype, it still leads to multiple testing. Consequently, we cannot formally exclude that false positive findings occurred here. However, the main results were confirmed in an independent dataset of patients, which is a strong argument against chance findings. In either group of patients, m-TOR, p70S6K or Raptor genetic polymorphisms had no effect on SRL AEs, except for the abovementioned m-TOR variant haplotype on Hb levels. The present study has certain limitations. Although two independent groups of patients were considered, both have a relatively small sample size. This is primarily due to the restricted use of the drug because of adverse events. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of the discovery study, with data collection from patient files. In contrast, for the confirmation study, clinical data were reported in a CRF and gathered in a prospectively built electronic database.

We have also to acknowledge that not all the precursors and effectors in the m-TOR signaling pathway were studied. However, we focused on proteins which interact directly with sirolimus: m-TOR is the principal target of SRL, Raptor is the regulatory protein associated to m-TOR in the m-TORC1 complex and p70S6K was previously chosen as a biomarker of SRL m-TOR inhibitory effect [22]. On the other hand, the 4EBP1 effectors inhibited by the phosphorylation of m-TOR have never been investigated. The study of other precursors or effectors might be less specific as they are only indirectly related to SRL activity.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence in favor of an association between the reduction of Hb and an m-TOR haplotype, in addition to SRL exposure. Prospective studies have to be performed in order to evaluate the effect of this haplotype on SRL efficacy, or rather benefit/risk ratio. We also confirmed the SRL concentration-related nature of dyslipemia, but identified no polymorphisms in m-TOR, p70S6K and Raptor which would result in an individual susceptibility to such AEs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was partly funded by Roche-Pharma, France

We thank INSERM, the CHU Limoges and the University of Limoges, as well as CHU Toulouse, the University Paul Sabatier of Toulouse and Roche-Pharma France for their support. We are grateful to F. Bousson for database handling, J. H. Comte for his contribution to laboratory analyses and K. Poole for manuscript editing. We thank Pr Y. Le Meur, Pr Y. Lebranchu and the CONCEPT study group.

References

- 1.MacDonald AS. A worldwide, phase III, randomized, controlled, safety and efficacy study of a sirolimus/cyclosporine regimen for prevention of acute rejection in recipients of primary mismatched renal allografts. Transplantation. 2001;71:271–280. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200101270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustine JJ, Knauss TC, Schulak JA, Bodziak KA, Siegel C, Hricik DE. Comparative effects of sirolimus and mycophenolate mofetil on erythropoiesis in kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:2001–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahe E, Morelon E, Lechaton S, Sang KH, Mansouri R, Ducasse MF, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in renal transplant recipients receiving sirolimus-based therapy. Transplantation. 2005;79:476–482. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000151630.25127.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahan BD. Sirolimus-based immunosuppression: present state of the art. J Nephrol. 2004;17 (Suppl 8):S32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morelon E, Stern M, Kreis H. Interstitial pneumonitis associated with sirolimus therapy in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:225–226. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, et al. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–468. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price DJ, Grove JR, Calvo V, Avruch J, Bierer BE. Rapamycin-induced inhibition of the 70-kilodalton S6 protein kinase. Science. 1992;257:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1380182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Kozlowski MT, Sugimoto T, Andrabi K, Weng QP, et al. Regulation of eIF-4E BP1 phosphorylation by mTOR. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26457–26463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soliman GA. The mammalian target of rapamycin signaling network and gene regulation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:317–323. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000169352.35642.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huber S, Bruns CJ, Schmid G, Hermann PC, Conrad C, Niess H, et al. Inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin impedes lymphangiogenesis. Kidney Int. 2007;71:771–777. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun C, Southard C, Di Rienzo A. Characterization of a novel splicing variant in the RAPTOR gene. Mutat Res. 2009;662:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen M, Cassidy A, Gu J, Delclos GL, Zhen F, Yang H, et al. Genetic variations in PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and bladder cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2047–2052. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lebranchu Y, Thierry A, Toupance O, Westeel PF, Etienne I, Thervet E, et al. Efficacy on renal function of early conversion from cyclosporine to sirolimus 3 months after renal transplantation: concept study. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1115–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Bakker PI, Yelensky R, Pe’er I, Gabriel SB, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Efficiency and power in genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1217–1223. doi: 10.1038/ng1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasiske BL, de Mattos A, Flechner SM, Gallon L, Meier-Kriesche HU, Weir MR, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor dyslipidemia in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1384–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaster R, Bittorf T, Klinken SP, Brock J. Inhibition of proliferation but not erythroid differentiation of J2E cells by rapamycin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:1181–1185. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fishbane S, Cohen DJ, Coyne DW, Djamali A, Singh AK, Wish JB. Posttransplant anemia: the role of sirolimus. Kidney Int. 2009;76:376–382. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chueh SC, Kahan BD. Dyslipidemia in renal transplant recipients treated with a sirolimus and cyclosporine-based immunosuppressive regimen: incidence, risk factors, progression, and prognosis. Transplantation. 2003;76:375–382. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000074310.40484.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer EJ, Lamon-Fava S, Cohn SD, Schaefer MM, Ordovas JM, Castelli WP, et al. Effects of age, gender, and menopausal status on plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol and apolipoprotein B levels in the Framingham Offspring Study. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:779–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann B, Schmid G, Graeb C, Bruns CJ, Fischereder M, Jauch KW, et al. Biochemical monitoring of mTOR inhibitor-based immunosuppression following kidney transplantation: a novel approach for tailored immunosuppressive therapy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2593–2598. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.