Abstract

Background/Aims

Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is the clinical presentation of primary infection with Epstein-Barr virus. Although the literature contains a massive amount of information on IM, most of this is related specifically to only children or adults separately. In order to distinguish any differences between preschool children and youth patients, we retrospectively analyzed their demographic and clinical features.

Methods

Records of patients hospitalized from December 2001 to September 2011 with a diagnosis of IM were retrieved from Peking University First Hospital, which is a tertiary teaching hospital in Beijing. The demographic data and clinical characteristics were collected.

Results

IM was diagnosed in 287 patients during this 10-year period, with incidence peaks among preschool children (≤7 years old, 130/287, 45.3%) and youth patients (>15 and <24 years old, 101/287, 35.2%). Although the complaints at admission did not differ between these two patient groups, the incidence of clinical signs (tonsillopharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and edema of the eyelids) was much higher in preschool children. The incidence of liver lesion and percentage of atypical lymphocytes were significantly higher in the youth group (P<0.001), and the average hospital stay was longer in this group. Pneumonia was the most common complication, and there was no case of mortality.

Conclusions

The incidence of IM peaks among preschool children and youth patients in Beijing, China. The levels of liver enzymes and atypical lymphocytes increase with age.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, Infectious mononucleosis, Preschool children, Youth

INTRODUCTION

Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is the clinical syndrome caused by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which presents with fever, pharyngitis, cervical adenopathy, and other various manifestations. EBV is a member of the human herpesvirus family, which has a double stranded DNA genome. As other members of herpesivirus family, lifelong latent infection in B lymphocytes is the result of the primary EBV infection. The virus could be reactivated when host immune response is severely impaired, like organ transplant recipient, taking glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressant for a long time, or infected with human immunodeficiency virus.

Seroprevalence of antibodies to EBV varied with socioeconomic conditions. In Tokyo (Japan), the positive rate of IgG antibody to viral capsid antigen (VCA) in children aged 5-to 7-year old was higher than 80% in early 1990s, contrasting to 59% in years 1995-1999.1 An early study published in 1994 addressed that almost all the children younger than 10 years in Hong Kong had been infected with EBV.2 A recent survey in year 2006 found that the overall seropositive rate of EBV VCA IgG was 83.6% in children under 14 years old in Beijing.3 The positive rate in rural areas was significantly higher (86.2%) than that in urban areas (80.8%). There is a delay trend of EBV infection in mainland China along with the improved economic and sanitary conditions.

Primary infection of EBV is frequently asymptomatic in infants and children. Even in susceptible youths and young adults, only 30-50% of the infected persons present as IM.4 In the USA, there is about 500 IM patients per 100,000 persons per year and the most of the patients are aged 15 to 24 years old.5 A retrospective study enrolled 418 hospitalized patients with IM younger than 18 years old in Beijing found that the incidence of IM peaked in children aged from 4 to 6 years.6 This was coincident with the study in Taiwan in 2005.7 Hospitalized children were their research group in both studies.

There was not comparison study focusing the different clinical features between children and youth patients with IM in a same area. Our study observed the similarities and differences of the clinical appearance between these 2 age groups.

METHODS

Patients

Records of patients discharged with diagnosis of Infectious mononucleosis (IM) between December 2001 and September 2011 were retrieved in Peking University First Hospital, a tertiary teaching hospital in Beijing, China.

All the patients in this study had at least 3 symptoms of fever, tonsillopharyngitis, rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, or splenomegaly apart from more than 10% of atypical-lymphocytes in peripheral blood and positive result of anti-EBV IgM.5 We excluded chronic active EBV infection patients and co-infection patients.

Data collecting

The demographic data and clinical information were obtained from each patient's record, the latter including underlying diseases, presenting symptoms and signs, laboratory parameters, and anti-EBV-IgM, serum EBV DNA load, patients' responses to treatment and outcome.

EBV DNA was detected by using fluorescent polymerase chain reaction diagnostic kit (Da An Gene Co., Ltd. Of Sun Yat-sen University, China), the lower limit for detection was 500 copies/ml.

Anti- EBV IgM was detected by ELISA kit (Sino-American biotechnology Co. Ltd, China) before 2005 and by chemiluminescence (DiaSorin LIAISON® Analyzer, Italy) after 2005.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study subjects and were summarized as the mean±standard deviation or the median (range) for continuous data. The Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test was employed to compare continuous variables between the groups, where appropriate. The chi-square test or the Fisher exact test was performed to compare categorical variables between groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software, version 9.1.3; a two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic data of all patients

We identified 287 patients with diagnosis of IM out of 484 patients that had EBV infection.

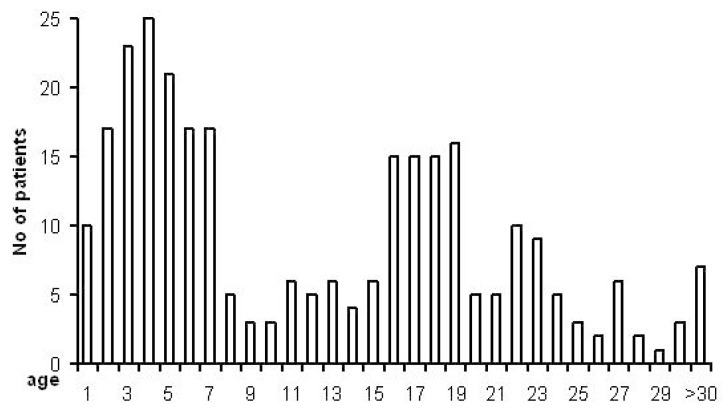

IM patients were aged from 0.6-to 39-year old with the median 11-year old. There were 2 peak ages of incidence: one was preschool children (≤7-year old, 130/287, 45.3%), the other one was youth (older than 15-but younger than 24-year old, 101/287, 35.2%). Patients' age distribution was shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of all patients with infectious mononucleosis.

There were 163 males (male:female=1:1.3). Only 46 patients (16%) had underlying diseases (Bacterial infections, cardiomyopathy, viral hepatitis caused by hepatitis A or B virus, fatty liver, and hyperthyroidism).

Clinical features of all patients

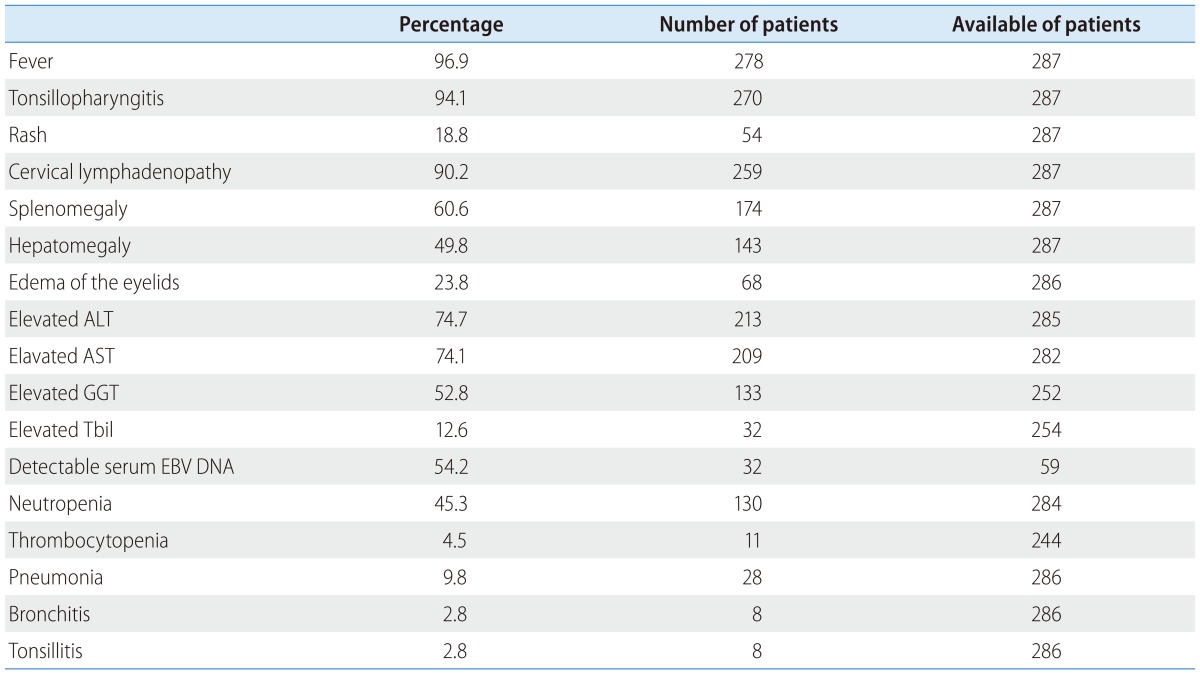

Fever (96.9%) and tonsillopharyngitis (94.1%) were the most common complains on admission. The median day of fever was 11 with ranging from 1 to 67 days. Rash (18.8%) was found in less than 1/5 of all IM patients of all ages. Lymphadenopathy could be found in 90.2% of patients. In laboratory examination, abnormal elevated liver enzymes were shown in nearly 4/5 of patients. There were less than 10% (28/287) patients with pneumonia. Patients' clinical characteristics on admission were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical features of all patients with infectious mononucleosis on admission

Neutropenia, neutrophil <1.5×109/L. Thrombocytopenia, thrombocyte <100×109/L. Pneumonia, parenchymal and interstitial impairments according to X-ray.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; PLT, platelet; Tbil, total bilirubin; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

Elevated ALT, AST, GGT and Tbil, above upper normal limits.

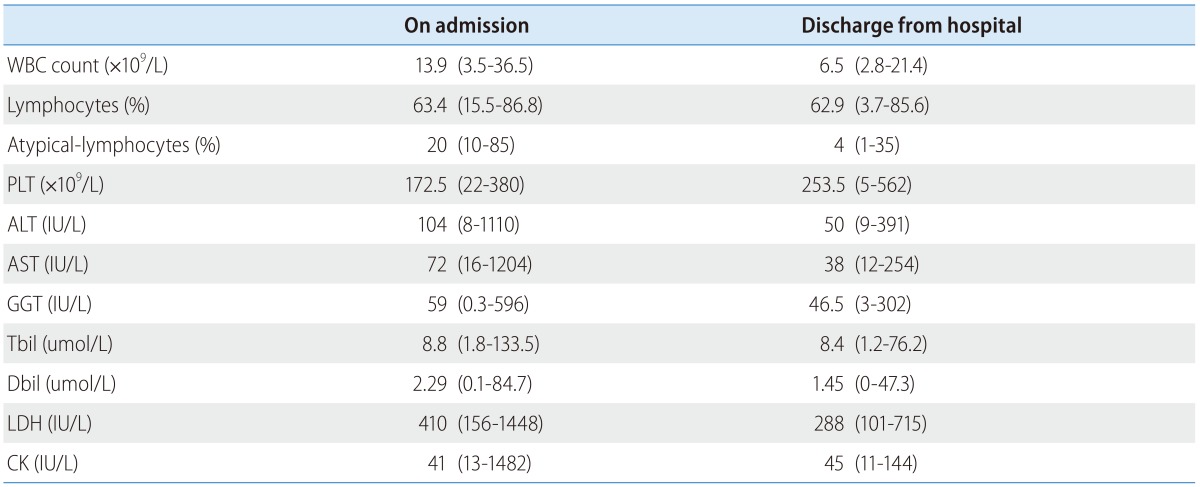

The results of blood regular test and liver enzymes were most common abnormal laboratory on admission. The median atypical-lymphocytes were 20% with the highest 85% on their first presentation in hospital. Nearly half (48.4%, 139/287) of patients' atypical-lymphocytes had recovered to less than 10% before they left hospital. More than half of them (57.6%, 80/139) were preschool children. Liver aminotransferases increased when admission and recovered before discharge from hospital. Total bilirubin elevated in 12.6% (32/254) patients on admission and did not return to normal in only 3.3% patients (6/183) before released from hospital. Over half of patients (52.8%, 133/252) had increased glutamyltranspetidase on admission at median 59 IU/L. Although the median gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) returned to normal range, there were nearly half of the patients (47.8%, 85/178) need to wait this parameter recovered at home. The comparison of laboratory parameters presented on Table 2.

Table 2.

Laboratory results of all patients with infectious mononucleosis on admission and before leaving hospital

All the data presented here were medians and range (minimum-maximum).

WBC: white blood cell; PLT: platelet; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; Tbil, total bilirubin; Dbil, direct bilirubin; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase.

All the patients stayed in hospital for a median 12 days. Only 21 (7.4%) patients had been treated with glucocorticoid during hospitalization. There was no dead case.

We confirmed that only 2 patients had complicated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.8 All these 2 patients were older than 7-year old and had detectable EBV DNA in serum samples on admission. They recovered well when they were released from hospital.

More clinical signs in preschool children on admission

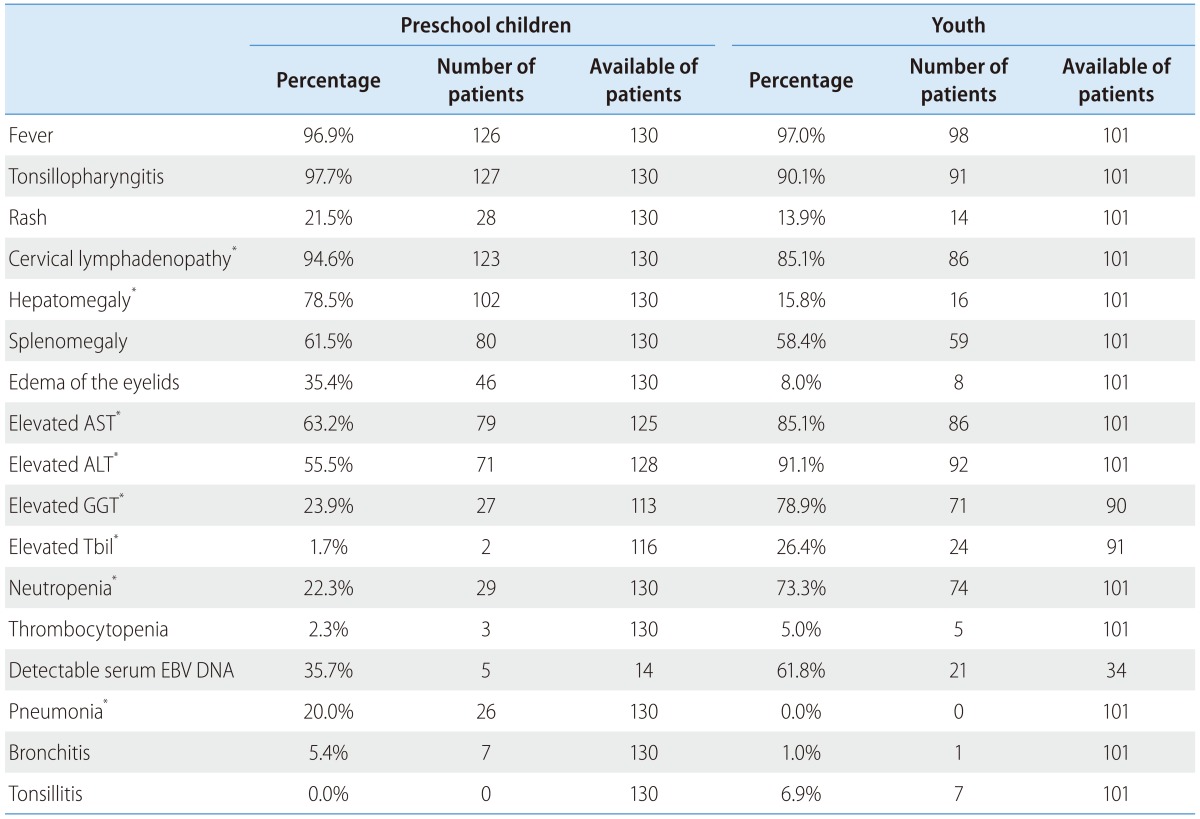

We noticed that there existed 2 age peaks of our 287 patients: preschool (≤7-year old, 45.3%) and youth (from 15-to 24-year old, 35.2%), as shown in Figure 1. We sought the similarities and diversities between these 2 groups of patients. We didn't find any difference in their sex distribution, underlying diseases, and the incident rates of fever and rash when they first presented at hospital. Interestingly, there were much more children with tonsillopharyngitis (97.7% vs. 90.1%, P<0.050), lymphadenopathy (94.6% vs. 85.1%, P<0.050), hepatomegaly (78.5% vs. 15.8%, P<0.001), and edema of the eyelids (35.4% vs. 8.0%, P<0.001) than that of youth on admission physical exam, as shown in Table 3. All of these indicated that there was no difference in complaints between the children and youth, but more signs were found on admission physical examinations.

Table 3.

Differences in clinical features between preschool children and youth patients

*There were significant differences between preschool children and adolencent patients, P<0.050. Elevated ALT, AST, GGT and Tbil, above upper normal limits.

Neutropenia, neutrophil <1.5×109/L. Thrombocytopenia, thrombocyte <100×109/L. Pneumonia, parenchymal and interstitial impairments according to X-ray.

Significantly liver lesion and higher percentage of atypical-lymphocytes in youth

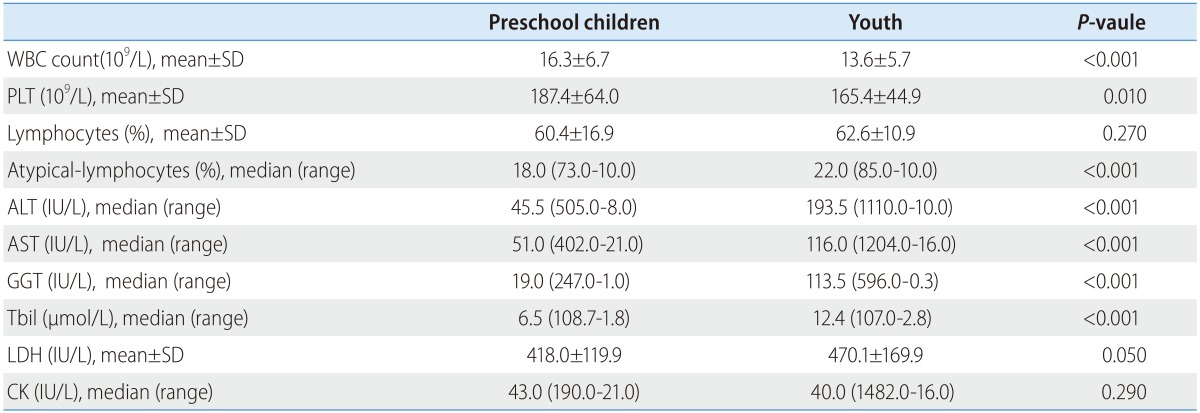

We found a significantly higher atypical-lymphocytes (median 22.0 vs. 18.0, P<0.001) but lower white blood cell count (13.6±5.72 vs. 16.3±6.7, P<0.001) and platelet count (165.4±44.9 vs. 187.4±64.0, P=0.010) in youth than preschool children.

Youth patients had significantly increased liver enzymes (including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and GGT, all P-values <0.001) than that of preschool children. Although the median value of total bilirubin was normal in both age groups, we found much more youth patients with abnormal total bilirubin (26.4%, 24/91) than preschool children (1.8%, 2/114). All the lab results listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Differences in laboratory results and hospital charges between preschool children and youth patients on admission

The data presented here were medians and range or mean±SD.

WBC, white blood cell; PLT, platelet; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; Tbil, total bilirubin; Dbil, direct bilirubin; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase.

Youth patients stayed in hospital for a longer time than that of preschool children (15.1±7.5 days vs. 11.2±4.7 days, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

We retrospectively analyzed the demographic and clinical records of 287 hospitalized patients admitted during 2001 to 2011. Preschool children and youth were 2 incident peak groups of IM. Previous studies found that preschool children had the highest incidence of IM in China.3,6-7,9 Youths aged 15-to 24- year old were the most common patients with IM in west countries.4-5,10 There were 2 explanations for the dissimilarities. Firstly, this shifting trend in the onset age of IM in Beijing probably reflects the improvement of China's socioeconomics. This consists with the serological survey in 2008. The seropositive rate decreased from 90% in 1970's to 82.5% in 2008 in preschool children in Beijing. The study also found that much more children in the rural areas (75.3%) suffered primary EBV infection than those lived in the urban areas (67.7%).3 Similarly shift was found in Japan1 by comparing seropositive rate in 1995-1999 (59%) with the early 1990s (>80%). Secondly, different study objects from previous reports could be another reasonable explanation. Previous reports only included patients younger than 18-year old6-7,9,11-12 or in university students.13-14 We collected patients with confirmed diagnose of IM at all ages, hospitalized in paediatrics department and non-paediatrics department.

Youth patients with over 10% of atypical-lymphocytoes without typical clinical triad of IM also need to find the evidence of EBV infection. The incidence of triad was significant lower in youth patients (74.3%) than in preschool children (90.8%), P<0.001. A significant higher atypical-lymphocyte percentage was one of notable features of our youth patients (Table 4). These were coincident with a previous study in patients aged 18-23 years.15 They also found a low incidence of triad of 68.2% and the specificity of clinical triad was 41.9% for IM diagnosis.

Higher occurrence of liver injury in youth patients was prominent in our study. Elevated aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase were the features of liver lesion in our study (Tables 1 and 4). Hyperbilirubinemia was not common in our patients (26.4%, 24/91) and disappeared before discharging from hospital. On the contrary, 36.8% of preschool patients had normal liver function and only 2 children had increased total bilirubin. Our results were consistent with previous studies in different age groups. Over 80% of older than 16-year IM patients presented abnormal aminotransferase, especially alanine aminotransferase.5,10,16 Jaundice was uncommon.5,10,16 Less than half of children (30.9%, 48.6%) with IM had liver dysfunction.6,11,17 The mechanism of liver involvement in IM patients was unclear, much less in the discrepancy between different age group. CD3 positive T lymphocytes were identified as the main lymphocytic infiltrate in EBV hepatitis, which were mainly cytotoxic CD8 positive T lymphocytes.18-20 Several studies have shown increased level of inflammatory cytokines in the sera of IM patients.10,21 Interferon-γ was a prominent one among these inflammatory cytokine. Increased level of Interferon-γ and its catabolic product may induce liver dysfunction.10,18 Further research about the pathogenesis was warranted.

There were pure clinical presentations of hospitalized patients with IM, which was the limitation of our study. Monitoring cytokine profile in serum and organs would be the next step.

In summary, both preschool children and youth were high-incidence group of IM in Beijing. Much more preschool children presented with clinical triad of IM. Youth patients with IM were marked with significant higher percentage of atypical-lymphocytes and elevated liver enzymes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China [81170386 and 81241013 to H. Z.].

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- EBV

Epstein-Barr vrus

- GGT

gamma-glutamyl transferase

- IM

infectious mononucleosis

- PLT

platelet

- Tbil

total bilirubin

- VCA

viral capsid antigen

- WBC

white blood cell

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Takeuchi K, Tanaka-Taya K, Kazuyama Y, Ito YM, Hashimoto S, Fukayama M, et al. Prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus in Japan: trends and future prediction. Pathol Int. 2006;56:112–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kangro HO, Osman HK, Lau YL, Heath RB, Yeung CY, Ng MH. Seroprevalence of antibodies to human herpesviruses in England and Hong Kong. J Med Virol. 1994;43:91–96. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du HJ, Zhou L, Liu HT, Wang Q, Zhan SB, Jia ZY, et al. A serological survey of Epstein-Barr virus infection in children in Beijing. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2008;22:30–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vouloumanou EK, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME. Current diagnosis and management of infectious mononucleosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19:14–20. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834daa08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao LW, Xie ZD, Liu YY, Wang Y, Shen KL. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of infectious mononucleosis associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection in children in Beijing, China. World J Pediatr. 2011;7:45–49. doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai MH, Hsu CY, Yen MH, Yan DC, Chiu CH, Huang YC, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis and risk factor analysis for complications in hospitalized children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005;38:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan CW, Chiang AK, Chan KH, Lau AS. Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis in Chinese children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:974–978. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000095199.56025.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odumade OA, Hogquist KA, Balfour HH., Jr Progress and problems in understanding and managing primary Epstein-Barr virus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:193–209. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00044-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González Saldaña N, Monroy Colín VA, Piña Ruiz G, Juárez Olguín H. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of infectious mononucleosis by Epstein-Barr virus in Mexican children. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:361. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang SC, Chen JS, Cheng CN, Yang YJ. Hypoalbuminaemia is an independent predictor for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in childhood Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis. Eur J Haematol. 2012;89:417–422. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macsween KF, Higgins CD, McAulay KA, Williams H, Harrison N, Swerdlow AJ, et al. Infectious mononucleosis in university students in the United kingdom: evaluation of the clinical features and consequences of the disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:699–706. doi: 10.1086/650456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford DH, Macsween KF, Higgins CD, Thomas R, McAulay K, Williams H, et al. A cohort study among university students: identification of risk factors for Epstein-Barr virus seroconversion and infectious mononucleosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:276–282. doi: 10.1086/505400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grotto I, Mimouni D, Huerta M, Mimouni M, Cohen D, Robin G, et al. Clinical and laboratory presentation of EBV positive infectious mononucleosis in young adults. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131:683–689. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803008550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kofteridis DP, Koulentaki M, Valachis A, Christofaki M, Mazokopakis E, Papazoglou G, et al. Epstein Barr virus hepatitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng CC, Chang LY, Shao PL, Lee PI, Chen JM, Lu CY, et al. Clinical manifestations and quantitative analysis of virus load in Taiwanese children with Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:216–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hara S, Hoshino Y, Naitou T, Nagano K, Iwai M, Suzuki K, et al. Association of virus infected-T cell in severe hepatitis caused by primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drebber U, Kasper HU, Krupacz J, Haferkamp K, Kern MA, Steffen HM, et al. The role of Epstein-Barr virus in acute and chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2006;44:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang MJ, Kim TH, Shim KN, Jung SA, Cho MS, Yoo K, et al. Infectious mononucleosis hepatitis in young adults: two case reports. Korean J Intern Med. 2009;24:381–387. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2009.24.4.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corsi MM, Ruscica M, Passoni D, Scarmozzino MG, Gulletta E. High Th1-type cytokine serum levels in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Acta Virol. 2004;48:263–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]