Abstract

Objective

Young men who have sex with men (MSM) and MSM of color have the highest HIV incidence in the US. To explore possible explanations for these disparities and known individual risk factors we analyzed the per-contact risk (PCR) of HIV seroconversion in the early highly active antiretroviral therapy era.

Methods

Data from three longitudinal studies of MSM, HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study, EXPLORE behavioral efficacy trial, and VAX004 vaccine efficacy trial were pooled. The analysis included visits where participants reported unprotected receptive anal intercourse (URA), protected receptive anal intercourse (PRA), or unprotective insertive anal intercourse (UIA) with an HIV seropositive, unknown HIV serostatus, or an HIV seronegative partner. We used regression standardization to estimate average PCRs for each type of contact, with bootstrap confidence intervals.

Results

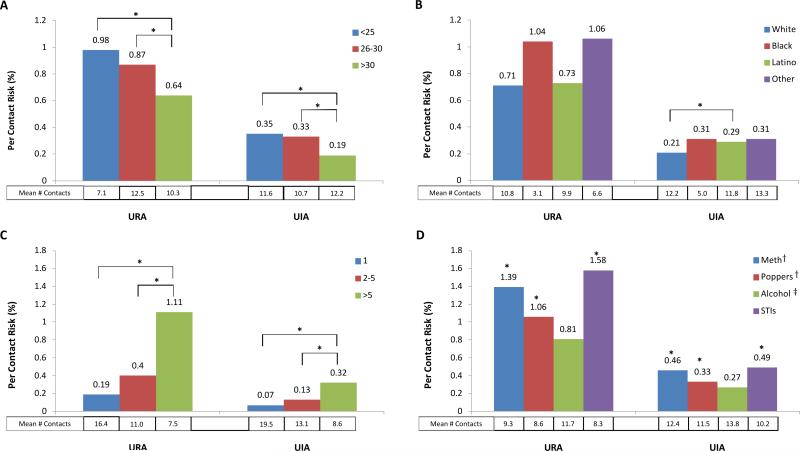

The estimated PCR was highest for URA with an HIV seropositive partner (0.73%; 95%BCI 0.45%-0.98%) followed by URA with a partner of unknown HIV serostatus (0.49%; 95%BCI 0.32%-0.62%). The estimated PCR for PRA and UIA with an HIV seropositive partner was 0.08% (95%BCI 0.0%-0.19%) and 0.22% (95%BCI 0.05%-0.39%) respectively. Average PCRs for URA and UIA with HIV seropositive partners were higher by 0.14-0.34% among younger participants and higher by 0.08% for UIA among Latino participants compared to White participants. Estimated PCRs increased with increasing number of sexual partners, use of methamphetamines or poppers, and history of sexually transmitted infection.

Conclusions

Susceptibility or partner factors may explain the higher HIV conversion risk for younger MSM, some MSM of color, and those reporting individual risk factors.

Keywords: HIV, MSM, USA, per contact risk

Introduction

Overall, new cases of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) have been stable in the United States (US) at approximately 50,000 per year.1 There has been an 12% increase in incidence among men who have sex with men (MSM) between 2007-2010.2 Young MSM are the most heavily impacted group in the US with an 22% increase in HIV incidence during this period.2 In addition to age disparities in HIV incidence, there are significant racial/ethnic disparities. In 2010, Black and Latino MSM represented the highest proportion of new HIV diagnoses among all MSM in the US, 36% and 22% respectively.2 Young Black MSM in particular have had the highest increase in HIV incidence between 2006 and 2010.2 However, little is known about why this occurs.3 Current data indicate that MSM of color have similar or lower individual risk behaviors, including number of anal sex partners and substance use, suggesting that differences in racial/ethnic assortivity in partner selection, partner serostatus, and prevalence of non-suppressed HIV viral load among HIV positive partners are likely driving the disparities.4-6

An analysis of per contact risk (PCR) of HIV seroconversion, the probability of HIV acquisition per sexual act, may contribute to our understanding of the extent to which disparities by race and age are driven by differences in infectiousness of partners and/or susceptibility of individuals, or, alternatively, by misclassification of HIV positive partners as HIV negative or of unknown serostatus.7,8 Previous estimates of PCRs for MSM have been based on relatively small samples, and used methods that were not designed to assess heterogeneity by race/ethnicity, number of sexual partners, substance use, and history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) which have been associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion.7,8 In this analysis, we use a new approach designed to accommodate heterogeneity.

We had two goals for this analysis. First, we compared the PCR of HIV seroconversion in the pre- and early highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, to identify the early impact of HAART on PCR. Second, we evaluated whether the PCR of sexual practices with known HIV positive partners differed by age and race/ethnicity. This analysis removes lack of knowledge of partner serostatus as a factor in age and race/ethnicity disparities, and may point to differences in infectiousness of partners and/or susceptibility of individuals to explain these disparities.

Methods

Participants and data collection

We identified four existing prospective longitudinal HIV prevention cohort studies of MSM in the US for inclusion in this analysis. The multisite Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Collaborative HIV Seroincidence Study (Jumpstart) was used to model PCR estimates in the pre-HAART era.9 This study enrolled 2,189 HIV uninfected MSM from three US cities from 1992-1994 who were followed for up to 18 months at semiannual intervals until study completion in 1995.

Data from the HIV Network for Prevention Trials (HIVNET) Vaccine Preparedness Study (VPS), the VaxGen VAX004 trial, and the EXPLORE study were combined to model PCR estimates from the early-HAART era.10 VPS enrolled 3,275 MSM in six US cities from 1995-1997 and they were followed every six months for 18 months of follow-up until study completion in 1999.11,12 The VAX004 trial enrolled 4,643 MSM in 57 US sites from 1998-1999 as part of a randomized placebo controlled efficacy trial of a recombinant gp120 HIV-1 vaccine which did not show efficacy in reducing HIV incidence.13 Participants were followed at six month intervals for 36 months and the study was completed in 2002. The EXPLORE study enrolled 4,295 MSM in six US cities from 1999-2001 into a randomized clinical trial of a ten-session behavioral intervention which showed no difference in HIV incidence rates between the control and active arms.14 Participants were followed every six months until study completion in 2003.

While there was some variability in specific enrollment criteria, all studies enrolled HIV negative men who reported anal intercourse with at least one male partner in the past 12 months. VAX004 was the only cohort study which excluded men who reported injection drug use (IDU) at baseline. Both EXPLORE and VAX004 excluded men who had been in mutually monogamous relationships for the previous year. Participants in all studies were asked to self-identify race/ethnicity at baseline. For the purposes of this analysis, we classified participants into one of four race/ethnicity categories: Black, Latino, White, or Other to maintain consistency across cohorts. In the analysis, men who self-identified as both Black and Latino contributed to PCR estimates for both groups. Self-reported sexual risk behavioral data were collected via audio-computer-assisted self interview (EXPLORE) or structured interview (Jumpstart, VAX004, and VPS) and included sexual behaviors in the past six months with partners of each HIV-serostatus type (negative, positive, or unknown). Sexual behaviors with sexual partners were defined as unprotected receptive anal intercourse (URA), unprotected insertive anal intercourse (UIA), or protected receptive anal intercourse (PRA). Other self-reported behavioral risk data included in this analysis were popper use, methamphetamine use, heavy alcohol use, and sexually transmitted infections (gonorrhea, syphilis, or chlamydia), as each has been found to independently predict HIV infection in MSM. Jumpstart participants who reported injection drug use (IDU) at baseline or follow-up were excluded from this analysis as it was associated with HIV seroconversion. However, IDU at baseline and follow-up was not significantly associated with HIV infection in the VPS, VAX004, and EXPLORE cohort studies, and exclusion didn't change our findings in sensitivity analysis, so participants who reported IDU were included in the adjusted analysis.

Per Contact Risk Estimation

Our previous estimates of PCRs were based on a Bernoulli model.7,8,15 Under this model, PCRs are assumed constant, and more distal cofactors for seroconversion, including age, race/ethnicity, numbers of partners, substance use, and STI, only affect risk through the numbers of contacts. However, this model does not accommodate heterogeneity in the PCRs. To do this, we used a pooled logistic model including the distal cofactors as well as numbers of contacts. Our approach allows heterogeneity in the PCRs in part by flexibly modeling the numbers of contacts, so that the absolute risk of five URA contacts with a positive partner can be more than 20% of the risk of 25 such contacts. In addition, because the logistic model is multiplicative, the absolute risk resulting from sexual contacts increases with the baseline risk determined by the cofactors. For example, the risk resulting from ten URA contacts with a positive partner is larger for a young man of color who reports multiple partners and methamphetamine use than for an older white man with none of these cofactors.

To obtain estimates of the PCRs, we estimate the absolute increment in risk resulting from each type of contact as the difference between the fitted risk for each participant-visit, and the potential risk if no such contacts of the given type had been reported.16 Then the PCRs are calculated from the number of contacts and the increment in absolute risk. In a final step, the PCRs are averaged, both overall and within subgroups defined by age, race/ethnicity, numbers of partners, substance use, and STI, with bootstrap confidence intervals. Additional details are provided in the online appendix.

Results

In Jumpstart, 1,813 participants, 4,168 unique visits, and 52 seroconversions were used to calculate the PCR in the pre-HAART era (Table 1). For the early-HAART era, we included 10,760 participants, 42,395 unique visits, and 584 HIV seroconversions from VPS, EXPLORE, and VAX004 (Table 1). The majority of participants from all the cohorts were over 30 years old, White, reported having more than six sexual partners, and having unprotected insertive or receptive anal sex in the six months prior to baseline. A higher proportion of participants reported an HIV seropositive sexual partner in EXPLORE (51%) and VAX004 (55%) compared to VPS (21%) or Jumpstart (18%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, risk characteristics, and cohort descriptive of Jumpstart, Vaccine Preparedness Study (VPS), EXPLORE, and VAX004 studies.

| Cohort |

p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jumpstart | VPS | EXPLORE | VAX004 | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 (%) | 370 (20) | 419 (18) | 715 (18) | 517 (11) | |

| 26-30 (%) | 485 (27) | 609 (27) | 847 (22) | 753 (16) | |

| >30 (%) | 958 (53) | 1,238 (55) | 2,351 (60) | 3,311 (72) | |

| Race/Ethnicity (N, %) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 1,422 (78) | 1,730 (76) | 2,864 (73) | 3,968 (87) | |

| Black | 102 (6) | 132 (6) | 283 (7) | 154 (3) | |

| Latino | 198 (11) | 289 (13) | 566 (14) | 320 (7) | |

| Other | 91 (5) | 115 (5) | 200 (5) | 139 (3) | |

| Education (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Less than High School | 50 (3) | 31 (1) | 56 (1) | 57 (1) | |

| High School Grad | 808 (45) | 841 (37) | 1,298 (33) | 1,546 (34) | |

| College Graduate | 663 (37) | 949 (42) | 1,717 (44) | 1,963 (43) | |

| Graduate Degree | 291 (16) | 445 (20) | 841 (22) | 1,015 (22) | |

| Risk Factor* | |||||

| Number of Sex Partners (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0-1 | 101 (6) | 29 (1) | 196 (5) | 426 (9) | |

| 2-5 | 611 (34) | 865 (38) | 974 (25) | 1,389 (30) | |

| ≥6 | 1,101 (61) | 1,372 (61) | 2,743 (70) | 2,766 (60) | |

| Unprotected anal sexa (%) | 1,277 (70) | 1,426 (63) | 3,406 (87) | 3,640 (79) | <0.001 |

| HIV+ Sex Partner (%) | 335 (18) | 477 (21) | 1,982 (51) | 2,498 (55) | <0.001 |

| Popper Use (%) | 704 (39) | 943 (42) | 1,942 (50) | 2,074 (45) | <0.001 |

| Heavy Alcohol Use (%) | 331 (18) | 523 (23) | 549 (14) | 816 (18) | <0.001 |

| Amphetamine Use (%) | 337 (19) | 362 (16) | 989 (25) | 816 (18) | <0.001 |

| Injection Drug Use, ever (%) | 0 (0) | 62 (3) | 648 (17) | 132 (3) | <0.001 |

| Sexually Transmitted Infection, self report (%) | 269 (15) | 188 (8) | 621 (16) | 347 (8) | <0.001 |

| Cohort Descriptives | |||||

| Total Participants | 1,813 | 2,266 | 3,913 | 4,581 | |

| Number of Visits | 4,168 | 5,041 | 17,657 | 19,697 | |

| Number of Seroconversions | 52 | 52 | 202 | 330 | |

In prior 6 months

insertive or receptive, with HIV positive, unknown serostatus, or negative partner

Per Contact Risk in pre- and early-HAART era

Overall, the estimated PCRs were similar in the pre- and early-HAART era (Table 2). The estimated PCR of HIV seroconversion for URA with an HIV seropositive partner were similar in the pre- (0.60%; 95% bootstrap confidence interval [BCI]: 0.34-1.09%) and early-HAART eras (0.73%; 95% BCI: 0.45-0.98%) (Table 2). URA with partners of unknown HIV serostatus was the second highest estimated PCR during the pre- (0.40% ; 95% BCI 0.26-0.59%) and early- (0.49%; 95% BCI: 0.32-0.62%) HAART eras. The estimated PCR was lowest for URA with HIV negative partners in both the pre- and the early-HAART era, 0.02% (95% BCI: 0-0.07%) and 0.03% (0-0.11%) respectively.

Table 2.

Per contact risks in pre Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) era (Jumpstart) and early HAART era (Vaccine Preparedness Study (VPS) EXPLORE, and VAX004 cohort studies)

| Partner Serostatus | Contact Type | Cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jumpstarta | VPS, EXPLORE, VAX004 | ||

| PCR (95% CI) | PCR (95% CI) | ||

| HIV Positive | URA | 0.60 (0.34-1.09) | 0.73 (0.45-0.98) |

| PRA | 0.04 (0.00-0.15) | 0.08 (0.00-0.19) | |

| UIA | 0.14 (0.04-0.29) | 0.22 (0.05-0.39) | |

| Unknown Serostatus | URA | 0.40 (0.26-0.59) | 0.49 (0.32-0.62) |

| PRA | 0.08 (0.01-0.16) | 0.11 (0.02-0.20) | |

| HIV Negative | URA | 0.02 (0.00-0.07) | 0.03 (0.00-0.11) |

| PRA | 0.09 (0.04-0.16) | 0.12 (0.06-0.18) | |

estimates based on model omitting covariates (see statistical methods)

HAART – Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

URA - Unprotected receptive anal intercourse

PRA - Protected receptive anal intercourse

UIA - Unprotected insertive anal intercourse

PCR – Per contact risk of HIV seroconversion

Despite relatively minor differences between pre- and early-HAART cohorts, we limited the remaining analyses to the latter 3 cohorts, to avoid confounding from unmeasured variables in the pre-HAART era. The estimated PCR for URA with an HIV positive partner was significantly higher than all other types of contacts, except URA with a partner of unknown HIV status (95% BCI for pairwise difference excludes zero) (Table 3). As expected, URA with an unknown serostatus partner was also significantly more risky than PRA with an unknown partner, and either URA or PRA with partners believed to be HIV negative.

Table 3.

Absolute differences in per-contact risk for HIV seroconversion with HIV positive partners, partners of unknown HIV serostatus, and HIV negative partners from early Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy era cohorts (Vaccine Preparedness Study, EXPLORE, and VAX004).

| Partner's HIV Serostatus | HIV Positive | HIV Unknown | HIV Negative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Type | PCR | PRA 0.08 | UIA 0.22 | URA 0.49 | PRA 0.11 | URA 0.03 | PRA 0.12 | |

| HIV Positive | URA | 0.73 | 0.66a | 0.51a | 0.24 | 0.62a | 0.70a | 0.61a |

| PRA | 0.08 | -- | −0.15 | −0.41a | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.05 | |

| UIA | 0.22 | -- | −0.27a | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.10 | ||

| HIV Unknown | URA | 0.49 | -- | 0.38a | 0.46a | 0.37a | ||

| PRA | 0.11 | -- | 0.08 | −0.01 | ||||

| HIV Negative | URA | 0.03 | -- | −0.09 | ||||

URA - Unprotected receptive anal intercourse

PRA - Protected receptive anal intercourse

UIA - Unprotected insertive anal intercourse

PCR – Per contact risk of HIV seroconversion

95% bootstrap confidence interval for pairwise difference excludes 0

Covariate Effects on HIV Seroconversion in VPS, EXPLORE, and VAX004

Next, we evaluated factors associated with HIV infection in the three early HAART longitudinal cohorts. Participants in VAX004 had higher odds of HIV seroconversion compared to VPS (OR 1.72; p=0.001) (Table 4). In combined cohort analysis, younger (<25 years) participants were at higher risk than older (>30 years) participants (OR: 1.31, p=0.03). Furthermore, Black participants were at greater risk compared to White participants (OR 1.78, p=0.002) while Hispanic participants had a trend toward higher risk (OR 1.26, p=0.08). Having greater than one sexual partner, any self-reported use of methamphetamines or poppers, heavy alcohol use, or history of STI in the prior 6 months were also associated with increased risk.

Table 4.

Bivariable factors associated with HIV seroconversion among MSM in longitudinal cohorts in the early highly active antiretrotiviral era (Vaccine Preparedness Study, EXPLORE, and VAX004).

| Variable | Visits | Seroconversions | Rate | OR (95% CI)e | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | VPS | 5,041 | 52 | 1.03 | ref | |

| EXPLORE | 17,657 | 202 | 1.14 | 0.87 (0.63-1.20) | 0.39 | |

| VAX004 | 19,697 | 330 | 1.68 | 1.72 (1.27-2.33) | 0.001 | |

| Age | <25 | 6,227 | 103 | 1.65 | 1.31 (1.03-1.66) | 0.03 |

| 26-30 | 8,572 | 129 | 1.50 | 1.11 (0.90-1.38) | 0.32 | |

| >30 | 27,596 | 352 | 1.28 | ref | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 34,271 | 454 | 1.32 | ref | |

| Black | 1,970 | 33 | 1.68 | 1.78 (1.23-2.56) | 0.002 | |

| Latino | 4,416 | 70 | 1.59 | 1.26 (0.97-1.64) | 0.08 | |

| Other | 1,738 | 27 | 1.55 | 1.16 (0.80-1.68) | 0.45 | |

| Sex Partners | 0-1 | 7,095 | 47 | 0.66 | ref | |

| 2-5 | 15,632 | 152 | 0.97 | 1.46 (1.04-2.04) | 0.03 | |

| >5 | 19,668 | 385 | 1.96 | 1.88 (1.34-2.63) | <0.001 | |

| Risk Factorsa | Methb | 5,187 | 170 | 3.28 | 1.67 (1.36-2.06) | <0.001 |

| Poppersb | 13,797 | 303 | 2.20 | 1.42 (1.19-1.71) | <0.001 | |

| Alcoholc | 3,536 | 69 | 1.95 | 1.33 (1.03-1.73) | 0.03 | |

| STId | 1,437 | 49 | 3.41 | 1.62 (1.18-2.23) | 0.003 | |

| Past IDU | 3,210 | 54 | 1.68 | 1.25 (0.90-1.74) | 0.18 | |

| Current IDU | 1,384 | 33 | 2.38 | 1.19 (0.78-1.80) | 0.43 |

VPS – Vaccine Preparedness Study

IDU – Injection drug use

STI- Sexually Transmitted Infection

In the prior 6 months

Any use (yes vs no)

Heavy use defined as 4 drinks per day or consumed an amount of alcohol equal to >5 drinks per occasion. (yes vs no)

Self report of gonorrhea, syphilis, or chlamydia (yes vs no)

All estimates are adjusted for numbers of unprotected and protected anal intercourse

Demographic and Risk Factor Disparities in Per Contact Risk of HIV Seroconversion

In evaluating differences by age, race/ethnicity, numbers of partners, substance use, and STI, we focused on the PCR for unprotected anal intercourse with known HIV seropositive partners, to eliminate knowledge of partner serostatus in these risk estimates. The PCR for URA with HIV seropositive partners was significantly higher for MSM younger than 25 years (0.98%), and between 25-30 years olds (0.87%) compared with MSM older than 30 years (0.64%) respectively (p<0.05) (Figure 1A). MSM younger than 25 years old had the highest PCR despite a lower mean number of reported contacts (7.1 vs 10.3). Similarly, the PCR for UIA with HIV seropositive partners was significantly higher for younger MSM (<25 years and 25-30 years) compared MSM older than 30 years (0.35% and 0.33% vs 0.19%; p<0.05) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Per contact risk of unprotected anal intercourse and mean number of reported contacts with a HIV seropositive partner stratified by (A) age, (B) race/ethnicity, (C) number of sexual partners, and (D) other risk factors . PCR estimates for the controls not reporting the other risk factors in (D) were uniformly lower than for the exposed (data not shown).

URA - Unprotected receptive anal intercourse

UIA - Unprotected insertive anal intercourse

STI- Self-reported Sexually Transmitted Infection (includes gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia)

* 95% bootstrap confidence interval for difference from reference group excludes 0

† - Any Use

‡ - Heavy Use

Similarly, some MSM of color had higher PCRs with HIV positive contacts (Figure 1B). We found weak evidence that PCR for URA with HIV seropositive contacts was higher for Black (1.04%) and participants classified as Other (1.06%) than for White participants (0.71%, p>0.05) (Figure 1B). Among Latino participants, there is stronger evidence for an elevated PCR for UIA with HIV seropositive contacts compared to White participants (0.29% vs 0.21%, p<0.05). Black participants reported the lowest mean number of contacts compared to all other racial groups, for both URA (3.1) and UIA (5.0). In contrast, numbers of contacts and PCRs for URA or UIA with HIV seropositive partners were similar in Latino and White MSM. The PCRs were significantly higher for those who reported more than one HIV positive partner (Figure 1C), with those reporting URA with more than five partners having the highest PCR. Those reporting methamphetamine or popper use, or a STI had significantly higher PCRs for URA and UIA with HIV seropositive partners compared to those who did not report these risk factors (Figure 1D).

Discussion

Our analysis of HIV seroconversion in four large cohorts of high risk MSM in the US suggests that the PCR of seven types of sexual contact were similar during the pre- and early-HAART eras. However, our new modeling approach, designed to accommodate heterogeneity, did identify substantial age and racial/ethnic disparities in the early HAART era, as well as differences in PCRs by numbers of sexual partners, STIs, and use of substances other than alcohol. These data support that susceptibility or partner factors may explain the higher HIV incidence among younger MSM, MSM of color, and those reporting multiple sexual partners, popper or methamphetamine use, or an STI.

The first estimates of PCR for MSM in the pre-HAART era reported a PCR of URA with an HIV positive partner of 0.82%.7 A more recent analysis of PCR from Australia in the early HAART era (2001-2004) reported similar PCR estimates for unprotected anal intercourse: 1.43% with ejaculation and 0.65% without ejaculation.8 A likely explanation for our finding of similar PCR estimates in the pre- and early-HAART eras is the relatively low proportion of HIV positive MSM with a suppressed HIV viral load. Based on current estimates, approximately 80% of those with HIV are aware of their infection, but less than 30% have a suppressed HIV viral load.17 Given the evolution in HIV testing and treatment recommendations, it is likely that rates of HIV viral load suppression were even lower when these cohort studies were conducted.18,19

There are several possible explanations for the finding of higher PCRs among young MSM. One is that younger MSM are less able than older MSM to negotiate safer sex with partners.20 For example, younger MSM may not have the skills or knowledge to navigate other risk reduction strategies with HIV positive partners (such as withdrawal prior to ejaculation) which may have a lower HIV risk.8 Survivor bias is another possible explanation for our findings. Because all of the participants had to be HIV negative at enrollment, the older MSM were likely able to remain HIV uninfected for longer than the younger MSM, potentially reflecting a reduced average susceptibility to HIV infection.21 Furthermore, we did not measure additional partner characteristics which may have been protective. For example, older MSM may also have older HIV positive partners who are often engaged in care and have lower HIV viral loads compared to younger HIV positive MSM.22 Finally, while there is evidence of increased biologic susceptibility for young women, there are no current studies to suggest a biological basis to explain these disparities for young MSM.23

We also found evidence that Latino MSM had a higher PCR for UIA with HIV seropositive partners, and inconclusive evidence that Black MSM and MSM classified as Other had a higher PCRs than White MSM for URA and UIA with HIV seropositive partners. If real, partner-level factors may help to explain this disparity.4,5,24 Specifically MSM of color report more assortive mixing by race, and HIV seropositive Black MSM are less likely to have suppressed HIV viral load.25,26 Nonetheless, the overall rate of HIV viral suppression was likely low in the early HAART era, suggesting that unmeasured partner-level factors, including STIs, may drive these disparities.22,27,28 Reporting bias could contribute, but we believe this is unlikely given the patterns in the total number of partners of each type and mean numbers of contacts. For this to hold, MSM of color would have to systematically and differentially under report unprotected contacts with HIV seropositive compared with unknown serostatus or negative partners which is not supported by the literature.5

These data also provide new insight into the increasing risk of HIV acquisition with multiple sexual partners and other risk behaviors. The lower PCR for men reporting URA or UIA with one HIV seropositive partner likely reflects two factors, both unmeasured: first, viral suppression may be more common among monogamous partners; and second, the likelihood of contact with at least one highly infectious partner increases with the number of HIV seropositive partners, because of heterogeneity in infectiousness.29 Furthermore, use of methamphetamines, poppers, and self-reported STI were also associated with higher PCR. Ulcerative and nonulcerative STIs are associated with increased risk through increasing susceptibility via mucosal breakdown and inflammation.30 The PCRs for poppers and methamphetamines are also high, suggesting that they may also increase susceptibility to HIV infection, although through less well elucidated mechanisms.

There are several important limitations to this study. The longitudinal cohorts analyzed in this study occurred early in the HAART era, and may not be reflective of later changes in HIV treatment. However, the current estimates are that only approximately 27% of MSM in the US are on HAART and virally suppressed, so even in 2012 the vast majority of HIV positive MSM in the US are not virally suppressed.22 Misclassification bias for HIV seronegative partners in the absence of an HIV disclosure discussion is also an important consideration. Our PCR estimate analysis focused on the highest risk sexual behavior for HIV transmission, URA and UIA with HIV positive partners, to minimize this bias. Despite the large sample size, there were relatively few visits and HIV seroconversions among Black MSM compared to other MSM. Many contact-and partner-specific factors that may explain heterogeneity in PCRs were not measured. Finally, while the new models fit the data better than Bernoulli models, they are nonetheless complicated, and we cannot rule out bias in our PCR estimates, including subgroup-specific PCRs and the differences between them.

Per contact risk of HIV seroconversion represents a novel method to evaluate possible explanations for drivers of HIV incidence. We identified higher per contact risk of HIV seroconversion among younger MSM, some MSM of color and those who reported use of poppers, methamphetamines, and a history of an STI in the US, supporting that susceptibility or partner characteristics are important in understanding why these disparities exist. The mechanisms for the increased HIV incidence and the individual and partner characteristics, beyond individual risk behavior, which drive these disparities warrant further exploration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), United States National Institutes of Health [R01-AI083060]. HMS received support from the NIMH of the U.S. Public Health Service Traineeship as part of the AIDS Prevention Studies T32 postdoctoral fellowship [MH-19105-23].

Statistical Appendix

Our previous estimates of per-contact risks (PCRs)1 were based on a so-called Bernoulli model. This model was also used by Jin et al 2 in their recent report, as well as other analyses of PCRs. The Bernoulli model assumes that seroconversion risk is exclusively determined by the numbers of contacts of each type reported, in combination with the corresponding PCRs. The basic Bernoulli model posits that , where Yij is an indicator for seroconversion for participant i at visit j, λk is the PCR for contact type k = 1, . . . , K, and nijk is the number of contacts of type k reported by the participant at that visit. Infection risk is the complement of the probability of escaping infection on all contacts.

The basic Bernoulli model also assumes that the PCRs are constant for each type of contact, an assumption that almost surely does not hold. Recently, Hughes et al 3 used a Bernoulli model developed by Jewell and Shiboski4 to assess PCRs for vaginal sex among serodiscordant couples in Africa. This model captures heterogeneity by allowing covariates to modify the number of contacts, using a complementary log-log link.

For MSM the problem is more difficult, because seroconversion risk is affected by both receptive and insertive anal sex contacts, with and without condom use, as well as contacts with multiple partners, including partners whose HIV serostatus is unknown or reported as negative. In our earlier work, we did attempt to let PCRs depend on covariates through a logit link, but this provided only very limited ability to model heterogeneity. To avoid these limitations, we have developed a new approach to more flexibly allow for heterogeneity in the PCRs.

Pooled logistic model

The new analysis uses a conventional pooled logistic model for seroconversion at each successive study visit. As in our earlier analysis, risk behaviors are treated as time-dependent covariates, updated at each visit, and used along with fixed demographic covariates to predict seroconversion at that same visit. In contrast to the Bernoulli model, this model allows seroconversion risk to depend directly on age, race/ethnicity, substance use, and STD, as well as the numbers of contacts; PCRs are estimated from the fitted model in a subsequent procedure, described below.

Calculation of PCRs

After the pooled logistc model is estimated, using standard logistic regression software, we calculate the PCR for contacts of type k = 1, . . . , K, in the following four steps:

The actual seroconversion Rij risk for participant i at visit j is estimated with all contact counts and covariates at their observed levels.

The potential risk for participant i at visit j is estimated, assuming no contacts of type k, holding all other contact counts and covariates at their observed levels.

We then use the actual and potential risk to calculate the PCR for each participant-visit where at least one such contact is reported, using a Bernoulli formulation. Specifically, we assume , where λijk is the PCR for contact type k for that participant-visit, and Rij, , and nijk are defined as before. This equation means that the probability of escaping infection given observed levels of exposure equals the potential probability of escaping infection from all other kinds of exposure, multiplied by the probabililty of escaping infection from all nijk contacts of type k. This gives for values of nijk > 0.

The marginal PCR λk is then calculated as average of the {λijk} across participant-visits with nijk > 0. Marginal PCRs for subgroups defined by age, race/ethnicity, numbers of partners, substance use, and STD are obtained by averaging over appropriate subsets of the {λijk}.

We obtain confidence intervals for each PCR using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap, with resampling of participants rather than participant-visits, to capture potential within-subject correlation. The resampling for the combined VPS, Explore, and Vaxgen data is also stratified on cohort, so that cohort sample sizes are preserved in each bootstrap sample. We also used bootstrapping for inference on pairwise di erences in PCRs between subgroups, as well as between PCRs for di erent types of contact.

Capturing heterogeneity

Our new approach potentially captures heterogeneity two ways:

The pooled logistic model uses cubic spline transformations of the contact counts, allowing for PCRs that differ according to the numbers of contacts reported, possibly reflecting frailty selection, steady relationships, or di erential reporting errors.

The model is multiplicative, so that for any given value of nijk, the difference between Rij and , and hence λijk, is larger if Rij is increased by covariates including age, race/ethnicity, numbers of contacts, substance use, and STD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Meeting where data were presented:

Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Atlanta; March 2013

Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, McKirnan D, MacQueen K, Buchbinder SP. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am J Epidemiol. 1999 Aug;150(3):306-311.

Jin F, Jansson J, Law M, et al. Per-contact probability of HIV transmission in homosexual men in Sydney in the era of HAART. AIDS 2010;24:907-13.

Hughes JP, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis 2012;205:358-65.

Jewell NP, Shiboski SC. Statistical analysis of HIV infectivity based on partner studies. Biometrics 1990;46:1133-50.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. [July 7, 2012];Department of Health and Human Services. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007-2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2012. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchbinder SP, Vittinghoff E, Heagerty PJ, et al. Sexual risk, nitrite inhalant use, and lack of circumcision associated with HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 May;39(1):82–89. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134740.41585.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007 Oct;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012 Jul;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006 Jun;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, McKirnan D, MacQueen K, Buchbinder SP. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am J Epidemiol. 1999 Aug;150(3):306–311. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin F, Jansson J, Law M, et al. Per-contact probability of HIV transmission in homosexual men in Sydney in the era of HAART. AIDS. 2010 Mar;24(6):907–913. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283372d90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchbinder SP, Douglas JM, McKirnan DJ, Judson FN, Katz MH, MacQueen KM. Feasibility of human immunodeficiency virus vaccine trials in homosexual men in the United States: risk behavior, seroincidence, and willingness to participate. J Infect Dis. 1996 Nov;174(5):954–961. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallabhaneni S, Li X, Vittinghoff E, Donnell D, Pilcher CD, Buchbinder SP. Seroadaptive practices: association with HIV acquisition among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e45718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seage GR, Holte SE, Metzger D, et al. Are US populations appropriate for trials of human immunodeficiency virus vaccine? The HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Apr;153(7):619–627. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.7.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn NM, Forthal DN, Harro CD, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine to prevent HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;191(5):654–665. doi: 10.1086/428404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartholow BN, Goli V, Ackers M, et al. Demographic and behavioral contextual risk groups among men who have sex with men participating in a phase 3 HIV vaccine efficacy trial: implications for HIV prevention and behavioral/biomedical intervention trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 Dec;43(5):594–602. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243107.26136.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T, Team ES. Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2004 2004 Jul 3-9;364(9428):41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson DP, Law MG, Grulich AE, Cooper DA, Kaldor JM. Relation between HIV viral load and infectiousness: a model-based analysis. Lancet. 2008 Jul;372(9635):314–320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vittinghoff E, Glidden D, Shiboski S, McColloch C. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dybul M, Fauci AS, Bartlett JG, Kaplan JE, Pau AK. HIV PoCPfTo. Guidelines for using antiretroviral agents among HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Annals of internal medicine. 2002 Sep;137(5 Pt 2):381–433. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-5_part_2-200209031-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DHHS Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agwu A, Ellen J. Rising rates of HIV infection among young US men who have sex with men. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009 Jul;28(7):633–634. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181afcd22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lederman MM, Alter G, Daskalakis DC, et al. Determinants of protection among HIV-exposed seronegative persons: an overview. J Infect Dis. 2010 Nov;202(Suppl 3):S333–338. doi: 10.1086/655967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC HIV in the United States: The Stages of Care CDC Fact Sheet. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi TJ, Shannon B, Prodger J, McKinnon L, Kaul R. Genital immunology and HIV susceptibility in young women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013 Feb;69(Suppl 1):74–79. doi: 10.1111/aji.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC Disparities in Diagnoses of HIV Infection Between Blacks/African Americans and Other Racial/Ethnic Populations — 37 States, 2005–2008. MMWR. 2011;60:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry M, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Same race and older partner selection may explain higher HIV prevalence among black men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2007 Nov;21(17):2349–2350. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f12f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009 Aug;13(4):630–637. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall HI, Byers RH, Ling Q, Espinoza L. Racial/ethnic and age disparities in HIV prevalence and disease progression among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jun;97(6):1060–1066. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005 Feb;191(Suppl 1):S115–122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalichman SC, Eaton L, Cherry C. Sexually transmitted infections and infectiousness beliefs among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for HIV treatment as prevention. HIV medicine. 2010 Sep;11(8):502–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004 Jan;2(1):33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]