Abstract

Objectives

To identify partner attributes associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among adolescents and summarize implications for research and prevention.

Design

Systematic review.

Methods

We identified peer-reviewed studies published 1990–2010 which assessed ≥1 partner attribute in relation to a biologically-confirmed STI among adolescents (15–24 years) by searching MEDLINE and included articles. Studies which included adolescents but >50% of the sample or with mean or median age ≥25 years were excluded.

Results

Sixty-four studies met eligibility criteria; 59% were conducted in high-income countries; 80% were cross-sectional; 91% enrolled females and 42% males. There was no standard “partner” definition. Partner attributes assessed most frequently included: age, race/ethnicity, multiple sex partners and STI symptoms. Older partners were associated with prevalent STIs but largely unrelated to incidence. Black race was associated with STIs but not uniformly. Partners with multiple partners and STI symptoms appear to be associated with STIs predominantly among females. Although significant associations were reported, weaker evidence exists for: other partner sociodemographics; sexual and other behaviors (sexual concurrency, sex worker, intimate partner violence, substance use, travel) and STI history. There were no apparent differences by STI.

Conclusions

Partner attributes are independently associated with STIs among male and female adolescents worldwide. These findings reinforce the importance of assessing partner attributes when determining STI risk. Prevention efforts should continue to promote and address barriers to condom use. Increased efforts are needed to screen and treat STIs and reduce risky behavior among men. A standard “partner” definition would facilitate interpretation of findings in future studies.

Introduction

Worldwide, individuals 15–24 years of age have the highest reported rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1 Although prevention efforts typically focus on individual behavior,2 a growing body of literature suggests that sexual partner characteristics independently influence STI risk. Particularly for females, risk may largely be determined by partner risk rather than individual behavior.3 Our objectives were to review peer-reviewed studies to identify partner attributes associated with STIs among adolescents and summarize implications for research and prevention efforts.

Methods

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE (PubMed) using the Medical Subject Heading terms: “Adolescents” AND (“Sexually Transmitted Diseases” OR “HIV”) AND “Sexual Partners” and “Risk Factors”. We also manually searched included articles.

Eligibility criteria

We included peer-reviewed studies published 1990–2010. Eligible studies used statistical tests to assess at least one sexual partner attribute in relation to a biologically-confirmed STI among persons 15–24 years of age, hereafter referred to as adolescents,4 at the individual-level. We included studies which tested for: Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), syphilis, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), hepatitis B (HBV) and/or Mycoplasm genitalium (MG). We included studies not limited to or stratified by adolescent age groups if >50% of the sample or mean or median age was <25 years.

Data extraction

We used a standard form to extract from eligible studies: study characteristics (first author; year of publication; recruitment venue; location; recruitment timeframe; duration of follow-up, if prospective; “partner” definition; STIs), participant characteristics (number, gender, age, race/ethnicity) and findings regarding associations between partner characteristics and STIs. Lastly, we categorized studies based on their design in assessing partner attributes in relation to STIs: couple-based, individual prospective and individual cross-sectional.

Results

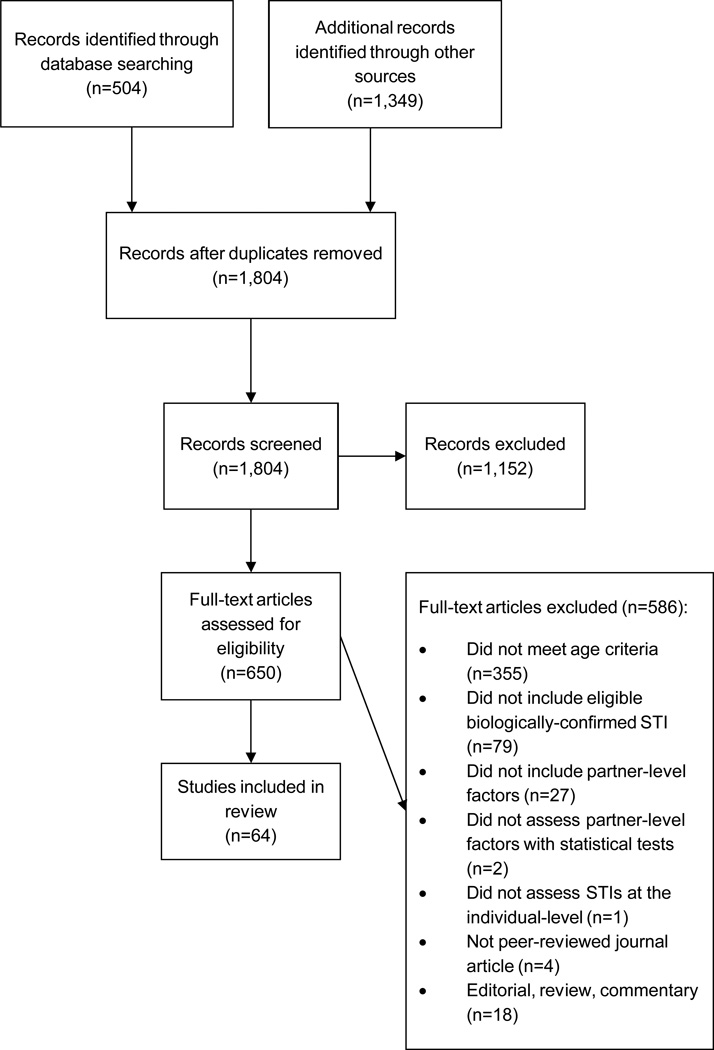

Our search yielded 1,804 unique records, all of which were screened (Figure 1). We assessed 642 650 articles for eligibility. We identified 64 eligible studies, including 1 (2%) couple-based study, 12 (19%) individual-prospective studies and 51 (80%) individual cross-sectional studies (Table 1). Thirty-eight (59%) were conducted in high-income countries;69 58 (91%) enrolled females, and 27 (42%) enrolled males. Of those which enrolled males, 1 (4%) was limited to men who have sex with men (MSM). Twenty-three (36%) studies were limited to HIV, 2 (3%) assessed other STIs in addition to HIV and 39 (61%) assessed ≥1 of the other eligible STIs. Only 5 studies (13%) conducted in high-income countries but 21 (81%) conducted in middle- or low-income countries assessed HIV.69

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram. Associations between partner-level factors and STIs among adolescents (1990–2010).

Table 1.

Characteristics and results of studies published 1990–2010 which assessed partner attributes in relation to STIs among adolescents

| Study sample§ | “Partner” Definition |

STIs assessed∫ |

Findings: Partner characteristics and significance* | Reference† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Couple-based studies | ||||

|

Subjects: 96 dyads (192 males and 192 females) participating in longitudinal study Age (years): 18–30 (median 22) Race/ ethnicity: 46% White Geography: San Diego County, CA1 Timeframe: 2000–2001 |

New sexual partner (someone with whom had vaginal intercourse for the first time within past 3 months) |

CT, TV | Partner has concurrent partners: Any STI: OR = 2.40 (0.9, 1.1), p=0.56; AOR = 3.58 (1.15, 11.2), p=0.28 |

Drumright (2004) 5 |

| Individual prospective studies | ||||

|

Subjects: 161 sexually experienced males and females STI-negative at baseline and sexually active during follow-up Age (years): 13–21 Race/ ethnicity: 39% African-American; 16% Caucasian; 21% Latino; 24% other Venue: HMO teen clinic Geography: US1 Timeframe: Not reported Duration of follow-up: 9 months |

Not reported | CT, GC, TV, bacterial vaginosis | Partner ≥4 years older: Any STI: 16.3% STI- vs. 42.3% STI+, p=0.002 Partner of African-American race (vs. all other racial/ethnic groups): Any STI: 27.4% STI- vs. 69.2% STI+, p=0.000 |

Boyer (2006)6 |

|

Subjects: 496 females enrolled in RCT Age (years): 14–18 Race/ ethnicity: 63.3% African-American, 22.0% White, 4.4% Hispanic, 10.3% Other Venue: Clinics Geography: Multiple US cities1 Timeframe: 1996–2000 Duration of follow-up: up to 4 months |

Sex partner within 60 days of baseline and within intervals since last clinic visit | Recurrent CT | Partners age ≥3 years older (vs. <3 years older): OR and AOR = NS Partner of African-American race (vs. White): OR = 1.27 (1.03, 1.56); AOR = NS Any partner same race as woman: 76.9% Yes (females without recurrent CT) vs. 63.8% Yes (females with recurrent CT), p<0.05 Concordant race of partner dyad (vs. discordant): OR = NS |

Magnus (2006)7 |

|

Subjects∞: 203 pregnant and 208 non-pregnant females Age (years): 14–19 Race/ ethnicity: 44% Black, 42% Hispanic, 14% White/other Venue: Public health clinics Geography: 3 cities in CT1 Timeframe:1998–2000 Duration of follow-up: 12 months ∞Partner analyses conducted among 175 pregnant females |

Not reported | CT, GC | Partner with STI risk (history of STD, sex with others in the past 6 months or ever injected drugs): Any STI: OR = 2.4 p=0.058 Partner >2 years older (vs. <2 years older): Any STI:OR = NS |

Ickovics (2003)8 |

|

Subjects: 6,177 ever sexually active females Age (years): 15–29 (74% <25) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Community-based Geography: Rakai, Uganda2 Timeframe: 1994–1998 Duration of follow-up: 30 months |

Most recent sexual partner | HIV |

Among all participants (vs. 0–4 years older):

Younger: Unadjusted PRR = 2.23 (1.60, 3.12); 5–9 years older: Unadjusted and Adjusted PRR = NS; Crude and Adjusted RR = NS; ≥10 years older: Unadjusted PRR = 1.32 (1.14, 1.54); Adjusted PRR = 1.28 (1.07, 1.52); Crude and Adjusted RR = NS; χ2 for HIV prevalence trend: p<0.001 Among 15–19 year olds (vs. 0–4 years older): Younger: Unadjusted PRR = NS; 5–9 years older: Unadjusted and Adjusted PRR = NS; Crude and Adjusted RR = NS; ≥10 years older: Unadjusted PRR = 2.43 (1.61, 3.68); Adjusted PRR = 2.04 (1.29, 3.22); Crude and Adjusted RR = NS; χ2 for HIV prevalence trend: p<0.001 Among 20-–4 year olds (vs. 0–4 years older): Younger: Unadjusted PRR = NS; 5–9 years older: Unadjusted and Adjusted PRR = NS; Crude and Adjusted RR = NS; ≥10 years older: Unadjusted PRR = 1.25 (1.00, 1.56); Adjusted PRR = NS; Crude and Adjusted RR = NS; χ2 for HIV prevalence trend: p=0.05 |

Kelly (2003)9 |

|

Subjects: 225 females CT+ at baseline Age (years): 14–18 Race/ ethnicity: 73.3% Black, 16.4% White, 10.2% Other Venue: Clinics Geography: Multiple US cities1 Timeframe: 1995–1997 Duration of follow-up: 4 months |

Not reported, obtained information about multiple partners | Recurrent CT |

Partner’s age ≥3 years older (vs. <3 years older): OR = NS | Kissinger (2002)10 |

|

Subjects: 319 homeless males and 217 homeless females Age (years): 13–20 Race/ ethnicity: 73.3% Black, 16.4% White, 10.2% Other Venue: Family planning or STD clinics Geography: Oregon1 Timeframe: 1995–1997 Duration of follow-up: 6 months |

Sexual partner in the past 3 months | CT, HSV-2 |

Partners ≥ 10 years older: Any STI: Males: OR = NS; Females: OR = 2.4 (1.1, 5.5) | Noell (2001)11 |

|

Subjects: 792 females CT+ at baseline Age (years): 14–34 (51.8% ≤19) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Clinics Geography: Multiple US cities1 Timeframe: Not reported Duration of follow-up: 4 months |

Not reported | Persistent/ recurrent CT |

Any partner ≥ 5 years older: RR= NS (at first return visit) All partners said they were treated: RR = NS (at both return visits) |

Whittington (2001)12 |

|

Subjects∞: 650 females Age (years): 14–19 Race/ ethnicity: 93% African-American, 7% White/Other Venue: Teen clinics Geography: Southeastern US city1 Timeframe: 1991–1993 Duration of follow-up: 6 months ∞Partner analyses conducted among 484 subjects who provided complete follow-up data |

Most recent sexual partner in the past 6 months | CT, GC, TV, syphilis, HBV, HSV-2 | Partner >21 years old: Any STI: RR = NS Partner has STI history: Any STI: RR = NS |

Bunnell (1999)13 |

|

Subjects∞: 196 CT-infected females randomized to different treatment arms and partners Age (years): 73% <25 Race/ ethnicity: 57% African-American Venue: Clinics Geography: Multiple US cities1 Timeframe: Not reported Duration of follow-up: 1 month ∞Partner analyses conducted among women |

Partner in the past 2 months | Persistent/recurrent CT | Partner may have multiple partners: RR: NS | Hillis (1998)14 |

|

Subjects: 86,844 sexually active females tested for CT Age (years): 15–19 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Family planning clinics Geography: Multiple cities in Region X1 Timeframe: 1988–1992 Duration of follow-up: up to 4 years ∞Partner analyses conducted among 26,921 females with >1 CT test |

Not reported | CT | Symptomatic (dysuria or discharge) sex partner (cross-sectional model): AOR = 2.3 (1.8, 3.0) Symptomatic (dysuria or discharge) sex partner (longitudinal model): AOR = 2.1 (1.7, 2.6) |

Mosure (1996)15 |

|

Subjects: 240 female sex workers HIV- at baseline Age (years): Mean 22 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Brothels Geography: Khon Kaen, Thailand2 Timeframe: 1990–1991 Duration of follow-up: 1 year |

Not reported | HIV | Sex with foreign Asian clients: crude IRR, POR and Adjusted POR = NS | Ungchusak (1996)16 |

|

Subjects: 1,150 postpartum females HIV- at baseline Age (years): Mean 24.5 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Antenatal clinics Geography: Butare, Rwanda2 Timeframe: 1989–1993 Duration of follow-up: 2 years |

Not reported. but 67.6% married or in common law union | HIV | Partner visits town daily: RR = 9.1 (3.7, 22.7) | Bulterys (1994)17 |

| Individual cross-sectional studies | ||||

|

Subjects: 1,090 females Age (years): 16–45 (median age 24) Race/ ethnicity: 44.7% White, 34.9% Black, 8.9% Asian, 2.7% Native American, 8.8% Other Venue: STD clinics Geography: Seattle, WA1 Timeframe: 200–2006 |

Most recent sexual partner | MG | Age difference: χ2 = NS Partner’s education: 22.7% <high school, 41.3% high school diploma, 25.3% some college, 10.7% college graduate or some graduate school among MG+ vs. 14.9% <high school, 31.8% high school diploma, 29.3% some college, 23.9% college graduate or some graduate school among MG-, p=0.017 Education discordance: χ2 =NS Partner income: 61.0% <$10,000, 39.0% ≥$10,000 among MG+ vs. 42.7% <$10,000, 57.3% ≥$10,000, p=0.006 Income discordance: χ2 =NS Partner has concurrent partners: χ2 =NS Partner has had STI: χ2 =NS Partner has used drugs: χ2 =NS Partner has used IV drugs: 1.3% MG+ vs. 7.1% MG-, p=0.053 Partner has spent ≥1 night in jail:25.2% Yes, 65.3% No, 9.3% Don’t know among MG+ vs. 45.1% No, 40.5% Yes, 14.4% Don’t know among MG-, p<0.001 Black (vs. non-Black partner): AOR = 3.4 (1.83, 6.29) |

Hancock (2010)18 |

|

Subjects: 74 MSM Age (years): 18–48 (median age 23, 75% ≤ 25) Race/ ethnicity: 61% White Venue: Screening program, internet, community, RDS Geography: North Carolina1 Timeframe: 2008–2009 |

3 most recent sex partners | Primary HIV | Mean age of sex partners ≥5 years older than participant: AOR = 2.0 (1.2, 3.3) Mean age of sex partners ≥10 years older than participant: AOR = 4.1 (1.5, 11) Mean age of sex partners ≥5 years older than participant (among participants ≤23 years): AOR = 2.5 (1.2, 5.4) Partner with discordant or unknown serostatus: AOR = 7.95 (1.39, 45.7), p=0.02 |

Hurt (2010)19 |

|

Subjects: 176 pregnant females Age (years): 15–19 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Primary health care clinics Geography: Zimbabwe2 Timeframe: 2002–2004 |

Not provided, though 90% married | HIV, HSV-2 |

Partner’s age:

HIV: OR = 1.09 (1.01, 1.19); HSV-2: OR = 1.09 (1.01, 1.78) Partner >25 years: HSV-2: AOR = 2.9 (1.2–6.9) |

Munjoma (2010)20 |

|

Subjects∞: 122 males and 103 females Age (years): 15–35 (mean 21.8 (women)) Race/ ethnicity: 41% Black Venue: Surveillance and DMV Geography: San Francisco, CA1 Timeframe: 2006 ∞Partner analyses among women presented as the sample of men did not meet age eligibility criteria |

Any sex partner in the past three months | GC |

Last sexual partner Black (vs. not Black):

Women: OR = 8.3 (3.0, 23.2) Partner incarcerated: Women: OR = 10.4 (2.0, 55.5); AOR = 6.2 (1.01, 38.4) |

Barry (2009)21 |

|

Subjects∞: 1,290 postpartum women (719 <25 years) Age (years): 12–47 (mean=24.6) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Maternity hospital Geography: Lima, Peru2 Timeframe: 2002–2004 ∞Multivariable partner analyses conducted stratified by age<19 (n=363) and age 20–24 (n=356) |

Current partner (age difference, “womanizer”, visiting prostitutes). Any current or previous partner (drug use, prison history) | CT |

Partner is “womanizer”:

All participants: χ2 = NS; <19 years: AOR = NS; 20–24 years: AOR = NS Partner drug history: χ2 = NS Partner prison history: χ2 = NS Partner visits prostitutes: χ2 = NS Age difference >5 years: χ2 = NS |

Paul (2009)22 |

|

Subjects: Sexually experienced males (n=200) and females (n=212) Age (years): 15–24 Race/ ethnicity: 41% White Venue: STD clinics Geography: Pittsburgh, PA1 Timeframe: 1999–2002 |

Both for main partner and most recent non-main partner | CT, GC, TV, syphilis, HSV-2, warts | Partner had STI in past year: Any STI: AOR = 3.4 (2.0, 5.7) >5 year age difference: Any STI: AOR = 2.6 (1.6, 4.5) Partner previously in jail: Any STI: AOR = NS Partner had other partners in past year: Any STI: AOR = NS Partner has alcohol problem: Any STI: AOR = NS Partner has marijuana problem: Any STI: AOR = NS Intermediate (vs. low) partner composite risk** score: Any STI: AOR (adjusted for demographics) = 2.2 (1.3, 4.4); AOR (adjusted for demographics and individual sexual activities) = 2.1 (1.0, 4.2) High (vs. low) partner composite risk** score: Any STI: AOR (adjusted for demographics) = 3.9 (1.9, 8.0); AOR (adjusted for demographics and individual sexual activities) = 3.4 (1.6, 7.0) **Composite risk for each participant based on 6 partner characteristics: ≥5 years age discordance, incarceration history, STI diagnosis in past year, other partners in past year, alcohol program, marijuana problem |

Staras (2009)23 |

|

Subjects: 41 males and 125 females who did not report injection drug use 12 months before HIV test Age (years): 17–55+ (59% <25years) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: HIV testing sites Geography: 4 oblasts in Russia2 Timeframe: 2003–2004 |

A regular or casual partner in 12-months before HIV test | HIV |

Regular partner HIV+:

Women: OR = 24 (5.4–110); Gender –adjusted OR = 26 (5.8–120) Regular partner of unknown HIV status: Men: OR = NS; Women: OR = NS; Gender-adjusted OR = NS Regular partner IDU: Men: OR = 1.9 (0.28, 13); Women: OR = 3.2 (1.5, 7.0); Gender –adjusted OR = 3.0 (1.5, 6.1); AOR (all participants) =3.58 (1.51, 8.49); AOR (participants who never injected drugs) = 3.26 (1.36, 8.34) Casual partner IDU: Men: OR = 1.2 (0.21, 6.7); Women: OR = 2.7 (0.27, 26); Gender-adjusted OR = 1.6 (0.42, 6.3) Unprotected sex with HIV+/unknown status regular partner: Men: OR = NS, AOR (all participants) = NS, AOR (participants who never injected drugs) = NS ; Women: OR = 8.1 (3.4, 19, ), AOR (all participants) = 5.35 (2.13, 13.4), AOR (participants who never injected drugs) = 5.61 (2.10, 15.0); Gender-adjusted OR = 3.9 (2.0, 7.7), Unprotected sex with partner with STI signs/ symptoms: Men: OR = NS, Women: OR = 5.5 (1.2, 26), Gender-adjusted OR = 4.1 (1.1, 15); AOR (all participants) = 6.39 (1.07, 38.1); AOR (participants who never injected drugs) = NS |

Burchell (2008)24 |

|

Subjects: 715 African-American females Age (years): 15–21 Race/ ethnicity: 100% African-American Venue: Reproductive health clinics Geography: Atlanta, GA1 Timeframe: 2002–2004 |

Any male sexual partner in past 60 days | CT, GC, TV | Partner drunk or high during sex at least once in past 60 days: Any STI: PR = 1.25 (0.99, 1.57), p=0.056, AOR = 1.44 (1.03, 2.02, p=0.03) | Crosby (2008)25 |

|

Subjects: 129 males and 30 females Age (years): Cases median = 22; controls median 23 Race/ ethnicity: 97% White, 1% Black, 2% Other Venue: Genitourinary clinic Geography: Glasgow, Scotland1 Timeframe: 2003–2004 |

3 most recent sexual partnerships | GC | Partner is of concordant gender: OR = 9.51(4.91, 18.39) p<0.0001; AOR = 47.77 (9.74, 234.38) p<0.001 Age difference (vs. <5 years): 5–9 years: OR = 2.44 (1.06, 5.60) p=0.04; ≥10 years: OR = 2.91 (1.03, 8.20) p=0.04 Partner is of discordant ethnicity: NS Concordant residential characteristics (Glasgow vs. other): OR = 2.32 (1.18, 4.57) p=0.01; AOR = 3.61 (1.24, 10.59) p=0.02 Concordant residential characteristics (within Glasgow): OR = NS |

Scoular (2008)26 |

|

Subjects: 5,854 sexually experienced females Age (years): 18–26 (mean 21.8) Race/ ethnicity: 68.2% White, 17.1% Black, 11.0 Latino, 2.9% Asian American, 0.8% Native American Venue: Wave III National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Geography: US National1 Timeframe: 2001–2002 |

Most recent male sex partner Most age discordant partner in past year |

CT |

Most recent partner age difference (years) (vs. −1 to 1):

−8 to −2: OR = 1.9 (1.0, 3.7); AOR = NS; 2 to 5: OR and AOR = NS; 6 to 36: OR and AOR = NS

2.1 (1.2, 3.4); AOR =1.7 (1.0, 2.8)

|

Stein (2008)27 |

|

Subjects: 2,932 males and females Age (years): 18–27 (77% <24) Race/ ethnicity: 50.2% White, 22.9% Black, 18.2% Latino, <1% Native American, <1% Asian Venue: Wave III National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Geography: US Nationa1l Timeframe: 2001–2002 |

Most recent sexual partnership | MG |

Partner’s race/ ethnicity (vs. White):

Black: PR = 32.20 (4.24, 245.06); Latino: PR = 11.00 (1.18, 103.43); Asian: PR = 14.00 (1.24, 157.70); Other: PR = 62.47 (4.27, 913.20) Participant’s and partner’s race/ ethnicity different: PR = 8.40 (2.51, 27.86) Age difference (vs. same age): Respondent younger ≥3 years: NS; Respondent older ≥3 years: PR = 3.10 (0.89, 10.68) Partner had concurrent partners: PR = 0.10 (0.03, 0.61) |

Manhart (2007)28 |

|

Subjects: 250 females Age (years): 13–18 Race/ ethnicity: 79.9% African-American, 19.6% Caucasian, 0.01% Other Venue: Pediatric ER Geography: Cincinnati, OH Timeframe: 2003–2004 |

Not reported | CT, GC | Partner penile discharge: Any STI: OR = 0.16 (0.45, 0.52) Ϙ ϘThe data provided show the odds of CT/GC among participants who did not report partner penile discharge relative to those who did is 0.16. The odds of CT/GC among those who reported partner penile discharge relative to those who did not appears to be 6.23, given the data provided.. |

Reed (2007)29 |

|

Subjects: Sexually active males (n=67) and females (n=99) Age (years): 14–19 Race/ ethnicity: 100% African-American Venue: Households Geography: San Francisco, CA1 Timeframe: 2000–2001 |

Any of up to 6 sex partners in the past 3 months | CT, GC | Any partner ≥5 years older: Any STI: OR = NS Any partner not African-American: Any STI: OR = NS Any partner with history of incarceration: Any STI: OR= 6.56 (1.77, 24.27) p<0.05 Any partner with history of gang membership: Any STI: OR = NS Any partner with perceived other partners: Any STI: OR = NS |

Auerswald (2006)30 |

|

Subjects: 1,550 females participating in RCT who reported sexual intercourse in 3 months prior to baseline assessment Age (years): mean 19.1 Race/ ethnicity: 58.1% White, 19.5% Hispanic, 17% African-American, 2.7% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2.6% Native American Venue: US Marine Corps recruit training Geography: US1 Timeframe: Not reported |

Last sex partner and lifetime partners | CT, GC, TV | Last sex partner ≥24 years (vs. <24): Any STI: χ2 = NS Age difference between participant and last sex partner: Any STI: χ2 = NS Race/ ethnicity of last sex partner: Any STI: African-American 31.2%, Asian/Pacific Islander 12.5%. White 9.3%, Hispanic 12.0%, Native American 22.2%, p<0.001 Partner(s) had sex with others: Any STI: Yes/not sure 17.1%, No 11.6%, p<0.01; AOR = 1.57 (1.15, 2.14) Partner(s) had STIs: Any STI: Yes/not sure 19.1%, No 13.2%, p<0.05; Race of last sex partner (vs. White): African-American: AOR = 4.84 (3.38, 6.94), p<0.001; Asian/Pacific Islander: AOR = NS; Hispanic: AOR = NS; Native American: 2.58 (1.06, 6.24), p<0.05 |

Boyer (2006)31 |

|

Subjects: 1,277 sexually experienced males Age (years): 15–26 (mean 19.2) Race/ ethnicity: Xhosa Venue: Schools Geography: Eastern Cape, South Africa2 Timeframe: 2002–2003 |

Lifetime sex partner | HIV | Ever had sex with a man: AOR = 3.61 (1.0, 13.0), p=0.05 | Jewkes (2006)32 |

|

Subjects: 1,295 sexually active females Age (years): 15–26 (mean 18.7) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Schools Geography: Eastern Cape, South Africa2 Timeframe: 2002–2003 |

Current or most recent main partner | HIV | Partner 3+ years older: OR = 1.69 (1.16, 2.48), p=0.007 Partner educated to matric or higher: OR = 1.91 (1.30, 2.78), p=0.001 |

Jewkes (2006)33 |

|

Subjects: 2,654 pregnant females Age (years): 14–43 (mean 24.6) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Antenatal care clinics at primary health clinics Geography: Moshi, Tanzania1 Timeframe: 2003–2004 |

Not reported, but 91% married or cohabitating | HIV |

Partner age (years) (vs. <25):

25–34: OR = 2.42 (1.34, 4.37) p=0.003; 35–71: OR = 3.62 (1.97, 6.66), p<0.001 Age difference (years) (vs. 0): −11 - −1: OR = NS; 1–10: NS; 11–41: OR = NS Partner has other women outside relationship (vs. No):Yes: OR = 22.57 (13.51, 37.69) p<0.001; AOR = 15.11 (8.39, 27.20), p<0.001; Don’t know: OR = 2.82 (1.75, 4.53) p<0.001 ; AOR: 2.70 (1.60, 4.57), p=0.001 Partner consumes alcohol (vs. No): Occasionally/weekly: OR = NS; Daily: OR = 2.28 (1.55, 3.36) p<0.001; AOR = 1.70 (1.06, 2.67), p=0.03; No response: NS Partner travels ≥4 times/month (vs. No): Yes: OR = 1.86 (1.35, 2.57) p<0.001; No response: NS Partners occupation (vs. professional): Driver: OR = NS; Army/ police force/ security guard: NS; AOR = NS; Tour guide/ miner: OR = 4.51 (1.36, 14.97), p=0.02; AOR = NS; Other: OR = NS Verbal or physical abuse by partner (vs. No): Yes: OR = 1.66 (1.13, 2.43), p=0.01; No response: NS Partner 1st person wished to share HIV results with: OR = 2.58 (1.76, 3.79), p<0.001; AOR = 1.71 (1.03, 2.84), p=0.04 |

Msuya (2006)34 |

|

Subjects: 31,762 females tested for CT and GC Age (years): 15–24 Race/ ethnicity: 90% White, 10% Black Venue: Family planning clinics Geography: Missouri1 Timeframe: 2001 |

Not reported | CT, GC | Partner with STD symptoms: GC: White: OR = 9.05 (5.16, 15.9); Black: OR = 5.23 (2.95, 9.29); CT: White: OR = 4.45 (3.39, 5.84); Black: OR = 2.18 (1.35, 3.55) | Einwalter (2005)35 |

|

Subjects: 8,735 males and females Age (years): 15–24 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Community-based Geography: Kwa-Zulu and Eastern Cape, South Africa2 Timeframe: 2002 |

Most recent sex partner | HIV | Partner ≥ 10 years older: AOR = 1.24 (0.82, 1.86), p=0.31 | Pettifor (2005)36 |

|

Subjects: 11,904 males and females Age (years): 15–24 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Community-based Geography: South Africa Timeframe: 2003 |

Not reported | HIV | Age difference with partner (vs. same age or younger):Men: 1–4 years older: OR = NS ≥5 years older: OR = NS; Women: 1–4 years older: OR = NS ≥5 years older: OR = 1.6 (1.0, 2.6); Women 15–19 years: 1–4 years older: AOR = NS; ≥5 years older: AOR = 3.22 (1.25, 8.33); Women 20–24 years: 1–4 years older: AOR = 2.28 (1.45, 3.59); ≥5 years older: AOR = NS | Pettifor (2005)37 |

|

Subjects: 208 females Age (years): 14–19 Race/ ethnicity: 100% Black, <1% White Venue: Clinic Geography: Baltimore, MD1 Timeframe: 2000–2002 |

Most recent main sex partner in the past 3 months | CT, GC | Partner sexual concurrency: OR: NS (main effects model); OR: 0.22 (0.06, 0.83) (interaction model, interaction term = partner sexual concurrency*gonorrhea rate per census block group: OR: 20.4 (1.07,3.87)) | Jennings (2004) 38 |

|

Subjects: Sexually active males (n=449) and females (n=359) Age (years): 15–24 (women), 20–34 (males) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Households Geography: Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso2 Timeframe: 2000 ∞Partner finding presented for women only since sample of men did not meet age eligibility criteria |

First sexual intercourse; non-marital partner in past 12 months | HIV | Age of first partner >24 years (vs 15–24): OR = 2.2 p=0.012; AOR = 4.30 (1.35, 13.6), p=0.01 Age difference with non-marital partner: χ2 = NS |

Lagarde (2004)39 |

|

Subjects: 202 males and 420 females Age (years): 18–25 (median 21) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Universities Geography: Seoul, South Korea2 Timeframe: Not reported |

Not reported | CT, GC | Partner symptomatic: Any STI: OR = NS | Lee (2004)40 |

|

Subjects: 4,066 sexually experienced females Age (years): 15–24 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Households Geography: South Africa2 Timeframe: 2003 |

Most recent sex partner in the past 12 months | HIV | Partner forced participant to have sex: χ2 = NS Partner ≥10 years older: χ2 = NS |

Pettifor (2004)41 |

|

Subjects: 2,859 puerperal females Age (years): 54% ≤23 Race/ ethnicity: 14% Black/other, 50% Brown, 36% White Venue: 24 Hospital maternity wards Geography: Brazil2 Timeframe: 2000 |

Not reported | Syphilis | Partner tested for syphilis during this pregnancy: OR = 1.79 (1.11, 2.89); AOR = 1.88 (1.13, 3.16) | Rodrigues (2004)42 |

|

Subjects: 169 unmarried pregnant females Age (years): 14–21 Race/ ethnicity: 100% African-American Venue: Prenatal clinic Geography: Atlanta, GA Timeframe: 1999–2000 |

Current steady sex partner | CT, TV | Partner at least 2 years older (vs. similar age): CT: PR = 3.43 (1.06, 11.11), p=0.02; AOR = 4.03 (1.08, 13.81), p=0.04; TV: PR = NS | Begley (2003)43 |

|

Subjects: 385 sexually active heterosexual males Age (years): 16–35 (55%<25) Race/ ethnicity: 100% Back Venue: Genitourinary medicine clinic and community Geography: Caribbean2 Timeframe: 2000–2001 |

Female sex partner in past 5 years | GC | Number of Black Caribbean partners: 10% 0, 58% 1, 16%2, 15% ≥3 among controls vs. 26% 0, 24% 1, 19% 2, 30% ≥3 among GC+, p<0.001 Number of Black Other partners: 87% 0, 9% 1, 7% ≥2 among controls vs. 73% 0, 12% 1, 15% ≥2 among GC+, p=0.001 Number of White partners: 77% 0, 14% 1, 9% ≥2 among controls vs. 51% 0, 22% 1, 26% ≥2 among GC+, p<0.001 Number of Indian partners: 97% 0, 3% ≥1 among controls vs. 91% 0, 9% ≥1 among GC+, p=0.017 1 Black Caribbean female partner (vs.0): AOR = ∼0.1 2 Black Caribbean female partners (vs.0): AOR = ∼0.1 >2 Black Caribbean female partners (vs.0): AOR = ∼0.05 ≥1 Indian female partner (vs.0): AOR = ∼10 |

Ross (2003)44 |

|

Subjects∞: 7,964 sexually active or ever married males and females Age (years): 13+ Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Households Geography: Masaka District, Uganda2 Timeframe: 1999–2000 ∞Partner analyses among participants 13–19 years of age presented (n=not reported) |

First sexual partner | HIV | Age of first sexual partner (among 13–19 year olds) (vs. same age): Older: AOR = NS; Younger: AOR = NS; χ2 for HIV prevalence trend: NS | Carpenter (2002)45 |

|

Subjects: 2,153 males and 2,276 females Age (years): 17–24 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Households Geography: Manicaland, Zimbabwe2 Timeframe: 1998–2000 |

Most recent sex partner And two most recent sexual partnerships within past month |

HIV |

Number of years most recent partner is Older: Men: Age-adjusted OR = 1.13 (1.02, 1.25), p=0.017; Women: Age-adjusted OR = 1.03 (1.00, 1.06), p=0.032; Men and women reporting sexual activity in past month: AOR = 1.04 (1.01, 1.08), p=0.007; Men and women reporting sexual activity in past 2 weeks: AOR = 1.04 (1.00, 1.07), p=0.039 Recent partner has other partners: Men: NS; Women: Age-adjusted OR = 2.06 (1.35, 3.14), p=0.001 |

Gregson (2002)46 |

|

Subjects: Sexually active males (n=723) and females (n=784) Age (years): 14–24 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Households Geography: Gauteng, South Africa2 Timeframe: 1999 |

Lifetime partners | HIV |

At least one partner was 5 years older/younger:

Men: OR = 4.1 (2.3, 7.2), p<0.001; Women: OR = 2.5 (1.8, 3.4), p<0.001 At least one casual partner had other sexual partners: Men: NS; Women: OR = 1.9 (1.3, 2.7), p=0.0004 At least one casual partnership with a married partner: Men: OR = 3.5 (1.5, 8.0), p=0.0030; Women: OR = 2.8 (1.8, 4.4), p<0.001 Sexual partnership with mineworkers: Men: OR = 3.3 (1.0, 11.3), p=0.048; Women: OR = 4.3 (1.9, 9.7), p=0.0005; AOR = 3.1 (1.2, 7.8), p=0.015 |

Auvert (2001)47 |

|

Subjects: 1,608 pregnant females Age (years): 15–45(mean 23.8) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Antenatal clinics Geography: Vitória, Brazil2 Timeframe: 1999 |

Not reported, but 70% were married or cohabitating | HIV, HBV, syphilis |

Partner prisoner:

HIV: OR = 13.6 (2.83, 65.01); Syphilis: OR = NS Partner drug abuser: HIV: OR = NS; HBV: OR = 5.4 (1.74, 17.06); Syphilis: OR = 3.0 (1.31, 6.88) Partner intravenous drug abuser: HIV: OR = 19.1 (3.89, 93.62); HBV: NS; Syphilis: OR = 7.2 (1.99, 25.91) |

Miranda (2001)48 |

|

Subjects: 243 females Age (years): 12–18 Race/ ethnicity: 73% African-American; 15% Hispanic; 12% White/Other Venue: Not reported Geography: 13 US cities1 Timeframe: 1996–1999 |

Up to 3 sex partners in the past 3 months | HIV | Partner male: OR = NS Mean age of partner (years): OR = 1.08 (1.03, 1.13), p=0.002 Mean age difference (years): 1.06 (1.01, 1.11), p=0.014; AOR = 1.06 (1.01, 1.12), p=0.018 Partner HIV-infected: OR = 7.25 (3.22, 16.33), p=0.000; AOR = 7.46 (3.20, 17.40), p=0.000 Partner injection drug user: OR = NS Partner had sex with other Men: OR = NS Partner had sex with other Women: OR = NS Partner trades sex: OR = NS |

Sturdevant (2001)49 |

|

Subjects: 214 males Age (years): 15–29 (72% <25) Race/ ethnicity: 93% Black Venue: STD clinic Geography: Newark, New Jersey1 Timeframe: 1995–1996 |

Most recent casual partner | GC |

Number most recent casual partner’s other partners during preceding month (vs. no casual partner):

Unknown: OR = 6.2 (3.2, 12.5); ≥1: OR = NS; 0: OR = NS Did not know number of sex partners of most recent casual partner: Among men with casual partners: OR = 3.9 (1.3, 11.6) |

Mertz (2000)50 |

|

Subjects: 1003 sexually experienced males and females Age (years): 14–45 (68% <25) Race/ ethnicity: 51% White Venue: STD clinics, adolescent medicine clinics, public and private health clinics Geography: Seattle, WA1 Timeframe: 1992–1994 |

Sex partner in previous 3 months | CT, GC |

Partner African-American:Participant White (vs. partner white):

GC: OR = 4.21∆; CT: OR = 2.05∆; Participant other race (vs. partner other race):

GC: NS; CT: OR = 2.67∆ Partner White:Participant African-American (vs. partner White): GC: NS; CT: OR = NS; Participant other race (vs. partner other race): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS Partner Other race:Participant White (vs. partner White): GC: OR = 0.55∆; CT: OR = 2.15∆; Participant African-American (vs. partner African-American): GC: NS; CT: NS Partner ≤19 years:Participant 20–29 years (vs. partner 20–29): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS Partner 20–29 years:Participant ≤19 years (vs. partner ≤19): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = 1.55∆ Partner less than high school education:Participant has high school education (vs. partner has high school education): GC: OR = 2.18∆; CT: OR = 1.27∆; Participant has more than high school (vs. partner has more than high school): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS Partner has high school education:Participant has less than high school (vs. partner has less than high school): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS; Participant has more than high school (vs. partner has more than high school): GC: OR = 2.44∆; CT: OR = 1.54∆ Partner has more than high school education:Participant has less than high school (vs. partner has less than high school): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = 0.37∆; Participant has high school education (vs. partner has high school): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS Partner had 1 sexual partner in past 3 months:Participant had 2 partners in past 3 months (vs. partner has had 2 partners): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS; Participants had ≥3 partners in past 3 months (vs. partner had ≥3 partners): GC: OR = 0.56∆; CT: OR = NS Partner has had 2 sexual partners in past 3 monthsParticipant had 1 partner in past 3 months (vs. partner has had 1 partner): GC: OR = 3.09∆; CT: OR = NS; Participant had ≥3 partners in past 3 months (vs. partner had ≥3 partners): GC: 0.39∆; CT: OR = NS Partner had ≥3 sexual partners in past 3 months:Participant had 1 partner in past 3 months (vs. partner had 1 partner): GC: OR = 3.09∆; CT: OR = 1.90∆; Participant had 2 partners in past 3 months (vs. partner had 2 partners): GC: OR = NS; CT: OR = NS ∆p<0.05 |

Aral (1999)51 |

|

Subjects: Sexually experienced males (n=118) and females (n=167) participating in longitudinal study Age (years): 13–21 Race/ ethnicity: 43% African-American, 15.1% White, 14.0% Hispanic, 28.4% Other Venue: Teen clinic Geography: San Francisco, CA1 Timeframe: 1994–1997 |

Not reported | CT, GC, BV, TV, syphilis warts, HSV-2 | Partner ≥2years Older: Any STI: χ 2= 5.56, p<0.05; AOR = 2.63 (1.22, 5.67) African-American sex partner (vs. all other racial/ ethnic groups): Any STI: χ2 = 4.17, p<0.05; AOR = NS |

Boyer (1999)52 |

|

Subjects∞: 1,149 female college students Age (years): 78% <25 Race/ ethnicity: Venue: University health center Geography: US1 Timeframe: 1995–1996 ∞Partner analyses among 26 cases and 77 controls consecutively enrolled after each case |

Not reported | CT | Partner with STD: All participants: OR = 9.9 (1.3, >100), p=0.05; Asymptomatic cases (n=12): NS | Cook (1999)53 |

|

Subjects: 231 males and 259 females participating in longitudinal study Age (years): 80% <25 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Households Geography: Mwanza Region, Tanzania2 Timeframe: 1993 |

Spouse, most recent if >1 | HSV-2 | Age of spouse (years) (vs. <20 years):Men: 20–24: OR = NS; ≥24: OR = NS; Women: 20–24: OR = NS; ≥24: OR = NS | Obasi (1999)54 |

|

Subjects: 2,784 female students Age (years): 15–23 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Secondary school clinics Geography: Antwerp, Belgium1 Timeframe: 1996–1997 |

Not reported | CT | Partner had a genital complaint (dysuria, urethral discharge or genital warts) in past 3 months: 9.8% subjects CT+ vs. 1.1% if partner did not have genital complaint, p=0.002; AOR 14.2 (3.17, 63.90), p=0.001 | Vuylsteke (1999)55 |

|

Subjects: 185 males and females (65% male) Age (years): 15–24 Race/ ethnicity: 80% African-American, 7% Hispanic, 5% White, 1% Asian, 7% Other Venue: STD control database Geography: San Francisco, CA1 Timeframe: 1990–1992 |

Lifetime partner | Repeated GC | Ever having sex partner inform patient of STD: χ2 = NS Any partner African-American: 36% vs. 56% (first-time infected vs. repeat infection), p=0.01 Non-main partner who is same race as patient: 67% vs. 82% (first-time infected vs. repeat infection), p=0.04 |

Klausner (1998)56 |

|

Subjects∞: 686 pregnant women participating in longitudinal study and male partners (n=not reported) Age (years): 14–41 (HIV+ median = 22, HIV- median = 24) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Hospital antenatal clinics Geography: Bangkok, Thailand2 Timeframe: 1991–1996 ∞Partner analyses conducted among pregnant women |

Current sex partner (husband or regular partner at enrollment) |

HIV | Partner is an IDU: 4.89 (1.78, 16.71), p<0.001; AOR = 3.57 (1.23, 10.41), p=0.02 Partner has had sex with female sex worker: OR = 6.27 (4.15, 9.48), p<0.001; AOR = 3.95 (2.51, 6.21), p<0.001 Partner has history of STI: OR = 7.21 (4.49, 10.66) p<0.001; AOR = 4.23 (2.81, 6.42), p<0.001 Frequency of sex with female sex workers while married (vs. never): Sometimes: OR = 2.52 (1.42, 4.50); Often: OR = 9.99 (2.33, 89.70); p<0.001 |

Siriwasin (1998)57 |

|

Subjects∞: 31,703 females Age (years): 12–81 (Mean 22.3 at family planning clinics, 25.2 at STD clinics) Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Family planning and STD clinics Geography: Multiple US cities1 Timeframe: 1989–1990 and 1993 ∞Partner analyses stratified by testing venue. Presented here are the findings among the 11,819 participants tested at family planning clinics in Washington |

Not reported | CT | Partner with ≥2 sex partners: OR = 1.9 (1.4, 2.5); AOR = NS Partner with discharge or dysuria: OR = 25 (1.6, 3.4); AOR = 2.3 (1.3, 4.0) |

Marrazzo (1997)58 |

|

Subjects: 148,650 sexually active females Age (years): 15–19 Race/ ethnicity: 90% White, 3% Black, 7% Other Venue: Title X family planning clinics Geography: Region X1 Timeframe: 1988–1992 |

Not reported | CT | Partner with multiple sex partners: OR = 1.70 (1.60, 1.82); AOR = 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) Symptomatic (dysuria or discharge) sex partner: OR = 2.92 (2.63, 3.25); AOR = 2.1 (1.9, 2.4) |

Mosure (1997)59 |

|

Subjects: 12,926 females tested for both CT and GC Age (years): 63.7% <25 Race/ ethnicity: 68.3% White, 4.1% Black, 13.4% Hispanic, 14.2% other Venue: Family planning clinic Geography: Colorado1 Timeframe: 1994–1995 |

Not reported | CT, GC | Sex partner with CT: CT: PR = 3.74 (2.72, 5.16); GC: PR = 6.90 (2.97, 15.99) Sex partner with GC: CT: PR =3.43 (1.87, 6.29); GC: PR = 45.97 (24.19, 87.37) |

Gershman (1996)60 |

|

Subjects: 220 females and 236 males Age (years): 13–19 Race/ ethnicity: 59% African-American; 38% Hispanic; 2% White Geography: New York City, New York Timeframe: 1988–1992 |

Lifetime partners | HIV | High-risk sex partner**: Women: 56% HIV+ vs. 7% HIV-, p<0.001 Sex with a man: Men: 100% HIV+ vs. 3% HIV-, p<0.001 **Defined as an IDU, MSM or HIV-positive partner |

Heffernan (1996)61 |

|

Subjects: 1,262 females Age (years): Mean 22 Race/ ethnicity: 99% White Venue: Family planning clinics Geography: Wisconsin1 Timeframe: 1990 |

Partner within past 2 months | CT | Partner with >1 partner (vs. No): Yes: RR = 2.27 (1.31, 3.92); Don’t know: RR = 1.75 (1.06, 2.89) Partner with gonorrhea (vs. No): Yes: RR = 6.33 (1.26, 31.80); Don’t know: RR = NS |

Addiss (1993)62 |

|

Subjects: 2,417 male military conscripts Age (years): 19–23 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Military conscription lottery Geography: 6 provinces, Northern Thailand2 Timeframe: 1991 |

Lifetime partner | HIV | Ever had sex with female: OR = 13.7 (3.39, 55.7) Ever had sex with male: OR = NS Ever had sex with commercial sex worker: OR = 7.40 (3.90, 14.0) |

Nelson (1993)63 |

|

Subjects: 1,115 male military conscripts Age (years): 95.2% 21 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Military conscription lottery Geography: Thailand2 Timeframe: 1991 |

Lifetime partner | HIV | Sex with female prostitute: RR = 5.8 (2.1, 15.7), p<0.001 | Nopkesorn (1993)64 |

|

Subjects: 1,082 pregnant females Age (years): 63.9% <25 Race/ ethnicity: 57.0% Black, 31.6% Hispanic, 5.6% White, 5.3% Haitian, 0.5% Other Venue: Antenatal clinic Geography: Palm Beach County, FL1 Timeframe: 1989–1991 |

Lifetime partner | HIV | HIV-infected sexual partner (HIV prevalence): 94.1% Yes vs. 3.5% No, p<0.001 Sexual partner from pattern II country (HIV prevalence): 9.2% Yes vs. 4.7% No, p=0.056 High-risk partner: AOR = 5.6 (2.7, 11) |

Ellerbrock (1992)65 |

|

Subjects: 244 puerperal females Age (years): Mean 23.7 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Maternity ward record review Geography: Edinburgh, Scotland Timeframe: 1985–1990 |

Not reported | HIV | Partner in paid employment: χ2 = NS | Johnstone (1992)66 |

|

Subjects: 356 female sex workers Age (years): Mean 22 Race/ ethnicity: Not reported Venue: Brothels Geography: Khon Kaen, Thailand2 Timeframe: 1985–1990 |

Not reported | HIV | Sex with non-Thai Asian clients in past 3 months: OR = 0.2 (0.02, 0.88); AOR = NS Sex with Western foreign clients in past 3 months: OR and AOR = NS |

Rehle (1992)67 |

|

Subjects: 849 females Age (years): Median 22 Race/ ethnicity: 64% White, 22% Black, 11% Hispanic, 2% Native American or Asian Venue: Clinics Geography: Milwaukee, WI1 Timeframe: 1986 |

Partner in past 3 months (≥1 partner) and partner within past 30 days (GC and urethritis) | CT | Partner with ≥1 partner (vs. No): Yes: RR = 1.9 (1.0, 3.4); Don’t know: RR = 2.1 (1.4, 3.2); AOR = 5.5 (4.0, 7.1) Partner urethritis (vs. No): Yes: RR = 2.6 (1.4, 4.7); Don’t know: RR = NS Partner with gonorrhea (vs. No): Yes: RR = 3.7 (1.7, 8.1); Don’t know: RR = 1.7 (1.1, 2.8) |

Addiss (1990)68 |

Venue: recruitment venue; Timeframe: Recruitment timeframe; HMO: Health maintenance organization; DMV: Department of Motor Vehicles: MSM: Men who have sex with men; RCT: Randomized-controlled trial; RDS: Respondent-driven sampling

High-income country

Middle- or low-income country

CT: Chlamydia trachomatis; GC: Neisseria gonorrhoeae; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HSV-2: Herpes Simplex Virus-2; MG: Mycoplasm genitalium; TV: Trichomonas vaginalis

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; NS: not significant; OR: odds ratio; PR: prevalence ratio: PRR: prevalence rate ratio; POR: prevalence odds ratio; RR: risk ratio. All parentheticals represent 95% confidence intervals.

Listed most to least recent and alphabetical within year

No standard “partner” definition was apparent. Definitions ranged from first sexual partner39,45 to most recent.9,13,18,26–28,33,36,38,41,46,50,70 Some studies collected information about multiple partners.10,19,23,26,27,31,39,46,49 Nearly one-third (31%) of studies conducted in middle- and low-income countries but none conducted in high-income countries defined “partner” as the participant’s spouse or enrolled a majority of married participants.

Given differences in STIs examined (HIV vs. other) and potential differences in findings due to conceptualization of “partner” as the participant’s spouse and the social and economic status of women, studies conducted in high-income countries and in middle- and low-income countries were analyzed separately.69 Table 2 summarizes the number of studies by partner attribute. There were no apparent differences in findings by STI.

Table 2.

Number of studies published 1990–2010 assessing associations between partner attributes and biologically-confirmed STIs among adolescents, by partner attribute

| Partner Attribute | By Type of Analysis: Number of studies with significant results/ Total number of studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-income Countries | Middle- and Low-income Countries | |||

| HIV | Other STIs | HIV | Other STIs | |

| Older age | Cross-sectional: 2/219,49 | Prospective: 26,11/76–8,10–13 Cross-sectional: 527,28,43,51,52/76,27,28,30,43,51,52 |

Prospective: 0/19 Cross-sectional: 89,20,33,34,36,37,39,46/109,20,33,34,36,37,39,41,45,46 |

Cross-sectional: 120/220,54 |

| Younger age | -- | Cross-sectional: 127/227,28 | Cross-sectional: 0/29,45 | -- |

| Race/ ethnicity | -- | Cross-sectional: 96,7,18,21,28,31,51,52,56/16,7,18,21,28,31,51,52,56 | -- | Cross-sectional:1/144 |

| Gender | Cross-sectional: 1/161 | Cross-sectional: 1/126 | Cross-sectional: 2/232,63 | -- |

| Education | -- | Cross-sectional: 2/218,51 | Cross-sectional: 1/133 | -- |

| Employment | -- | -- | Cross-sectional: 2/234,47 | -- |

| Income | Cross-sectional: 0/166 | Cross-sectional: 1/118 | -- | -- |

| Incarceration | -- | Cross-sectional: 221,30/321,23,30 | Cross-sectional: 1/148 | Cross-sectional: 148/222,48 |

| Travel | -- | -- | Cross-sectional: 2/217,34 | -- |

| Foreigner | -- | -- | Prospective: 0/116 Cross-sectional: 2/216,67 |

|

| Sexual concurrency | -- | Couple-based: 1/15 Cross-sectional: 228/318,28,38 |

-- | -- |

| Multiple partners | -- | Prospective: 0/114 Cross-sectional: 731,50,51,58,59,62,68/1031,50,51,58,59,62,68 |

Cross-sectional: 4/434,46,47,57 | Cross-sectional: 0/122 |

| Sex worker | -- | -- | Cross-sectional: 2/263,64 | -- |

| Intimate partner violence | -- | -- | Cross-sectional: 134/234,41 | -- |

| Substance use | Cross-sectional: 0/149 | Cross-sectional: 125/318,23,25 | Cross-sectional: 4/424,34,48,57 | Cross-sectional: 148/222,48 |

| STI history | -- | Prospective: 0/113 Cross-sectional: 223,31/323,31,56 |

Cross-sectional: 1/157 | -- |

| STI symptoms | -- | Prospective: 1/115 Cross-sectional: 6/653,60,62,68 |

Cross-sectional: 1/124 | Cross-sectional: 0/140 |

| Known to have STI | Cross-sectional: 2/249,65 | Cross-sectional: 4/453,60,62,68 | -- | -- |

HIGH-INCOME COUNTRIES

Age

Seven19,27,28,43,49,51,52 of 96,19,27,28,30,43,49,51,52 studies found older partner age significantly positively associated with prevalent STIs. Older partner age was associated with an increased likelihood of prevalent infections across STIs (HIV,19,49 CT,27,43,51 MG,28 and a composite STI measure52); among males19,28,51,52 and females;27,28,43,49,51,52 and across definitions of older age and partners.

Only 26,11 of 76–8,10–13 studies which explored older age in relation to incident STIs found significant associations. A partner ≥10 years older was positively associated with incident CT/HSV-2 among homeless females but not males.11 Among males and females at a health maintenance organization, a partner ≥4 years older was associated with increased STI acquisition.6

In national studies in the United States (US), younger partner age was unrelated to MG prevalence,28 but females whose most age discordant partner in the past year was 2–8 years younger were more likely to be infected with CT.27

Race/ethnicity

Ten6,7,18,21,28,30,31,51,52,56 of 116,7,18,21,26,28,30,31,51,52,56 studies which investigated race/ethnicity were US-based; 9 of the 10 reported significant findings.6,7,18,21,28,31,51,52,56 In the 2 prospective studies, an African-American partner was associated with STI acquisition 6,7 In cross-sectional studies, Black or African-American race was positively associated with MG,18,28 GC,21 repeat GC56 and composite STI measures.31,52 One study reported an African-American partner was significantly associated with GC and CT among White and “Other” males and females, but not among African-Americans.51 A Hispanic or Asian partner was associated with increased prevalence of MG in a national study.28 In Scotland, a partner of discordant ethnicity was unrelated to GC.26

Gender

Two cross-sectional studies assessed partner gender in relation to STIs.26,61 In the US, a greater proportion of HIV-positive males reported sex with a man.61 In Scotland, males and females with a partner of concordant gender were more likely to be infected with GC.26

Education

Two cross-sectional studies explored education and STIs; both reported significant findings.18,51 One found that MG-infected individuals were more likely to have a partner with a high school diploma or less, but education discordance was unrelated to MG.18 The other reported that males and females with partners less highly educated than themselves experienced a greater likelihood of CT and GC.51

Income

Two cross-sectional studies explored partner income and STIs,18,66 but only 1 reported significant findings.18 MG-infected females in Seattle were significantly more likely to report a partner earning <$10,000,18but a partner in paid employment was unrelated to HIV in Scotland.66

Incarceration

Two21,30 of 321,23,30 cross-sectional studies reported that partner’s incarceration history was related to STIs. Incarceration history was positively associated with GC and GC/CT among females21,30 but unrelated to a composite STI measure among STD clinic attendees.23

Sexual Concurrency

Four studies assessed partner’s concurrency;5,18,28,38 three reported significant findings.5,28,38 The couple-based study found concurrency reported by the partner positively associated with CT/TV.5 A national study found increased MG prevalence among adolescents who perceived their most recent sexual partner had concurrent partners,28 but another found no association among STD clinic attendees.18 Another study reported that sexual concurrency and gonorrhea rate per census block group were interactively but not independently associated with CT/GC.38

Multiple partners

One prospective study reported a partner with multiple sexual partners was unrelated to persistent/ recurrent CT.14 Seven31,50,51,58,59,62,68 of 1023,30,31,49–51,58,59,62,68 cross-sectional studies which examined a partner with multiple partners reported significant positive findings.

Substance use

Only 218,25 of four18,23,25,49 cross-sectional studies assessing partner substance use reported significant findings. Partner drug use was unrelated to HIV49 and MG.18 However, injection drug use was marginally associated with MG.18 Partners with alcohol and marijuana problems were unrelated to a composite STI measure,23 but a partner in the past 60 days who was high or drunk during sex was associated with increased odds of CT/GC/TV.25

STIs

The single prospective study reported that a partner with an STI history was unrelated to STI acquisition,13 but 223,31 of 323,31,56 cross-sectional studies reported significant associations. Partner STI history was associated with CT/GC/TV among female Marine Corps recruits31 and a composite STI measure among STD clinic attendees23 but unrelated to repeat GC.56

Seven studies explored STI symptoms; all exclusively enrolled females and reported significant positive associations.15,29,35,55,58,59,68 A symptomatic partner was associated with an increased likelihood of CT in longitudinal15 and cross-sectional analyses. 15,35,55,58,59,68 Symptomatic partners were also positively associated with GC and CT/GC.29,35 Unsurprisingly, a known infected partner was positively related to STIs in all 6 cross-sectional studies.49,53,60,62,65,68

MIDDLE- AND LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES

Age

Eight9,20,33,34,36,37,39,46 of 109,20,33,34,36,37,39,41,45,46 studies which assessed older partner age and prevalent HIV reported significant positive associations. However, older age was unrelated to HIV incidence in the single prospective study.9 Two cross-sectional studies assessed older age and HSV-2,20,54 only one of which reported significant findings.20 Pregnant Zimbabwean teens with a partner >25 years were more likely to be infected,20 but partner age >24 years was unrelated to HSV-2 among Tanzanian males and females.54 Both cross-sectional studies found no association between younger partner age and HIV prevalence.9,45

Race/ethnicity

Only one cross-sectional study assessed race/ethnicity. Among Black males in the Caribbean, a Black Caribbean female partner was associated with decreased odds of GC.44

Gender

Both cross-sectional studies assessing gender reported significant results.32,63 Among South African males, a male partner was associated with an increased likelihood of HIV.32 Among Thai military conscripts, a female partner was associated with an increased likelihood of HIV, but male partner gender was unrelated.63

Education

Only one cross-sectional study assessed education. Among South African females, a partner educated to matric or higher was positively associated with HIV.33

Employment

Two cross-sectional studies assessed employment and HIV; both reported significant associations.34,47 In Tanzania, HIV was increased among pregnant women whose partner was a tour guide or mineworker.34 In South Africa, intercourse with a mineworker was associated with increased likelihood of HIV.47

Incarceration

One48 of 222,48 cross-sectional studies found incarceration history related to STIs. A partner with an incarceration history was positively associated with HIV but unrelated to syphilis among pregnant women in Brazil48 and unrelated to CT among postpartum mothers in Peru.22

Travel

Both studies assessing travel reported significant findings.17,34 In Rwanda, HIV acquisition was increased among women whose partners traveled to town daily.17 In Tanzania, the odds of HIV were increased among pregnant women who reported their partner traveled ≥4 times/ month.34

Foreigner

Two studies among sex workers in Thailand examined sex with foreigners and HIV.16,67 One found foreign Asian clients were significantly associated with decreased HIV prevalence but were unrelated to incidence.16 Another found foreign Asian clients were associated with decreased odds of HIV in unadjusted but not adjusted analyses; Western foreign clients were unrelated to HIV.67

Multiple partners

Four cross-sectional studies assessed HIV and a partner with other partners; all reported significant positive associations.34,46,47,57 HIV was also increased among pregnant Thai women who reported a partner who had sex with sex workers, and risk increased with more frequent patronage.57 In contrast, CT was unrelated to partner’s patronage of sex workers among Peruvian postpartum women.22

Sex worker

Sex with a sex worker was associated with an increased likelihood of HIV in 2 cross-sectional studies among Thai military conscripts.63,64

Intimate partner violence

Two cross-sectional studies assessed intimate partner violence and HIV,34,41 but only 1 reported significant findings.34 HIV was increased among pregnant Tanzanian women who experienced verbal or physical abuse 34 but was unrelated to forced sex by the most recent partner among South African females.41

Substance use

Four of five cross-sectional studies assessing substance use reported significant findings.24,34,48,57 All 3 studies which examined injection drug use and HIV found an increased likelihood.24,48,57 Among pregnant Brazilian women, an injecting partner was associated with an increased likelihood of syphilis, and partner drug abuse was positively associated with HBV.48 Alcohol use was positively associated with HIV among pregnant Tanzanian women,34 but partners with a drug history were unrelated to CT among postpartum Peruvian women.22

STIs

One cross-sectional study reported on STI history. A partner with an STI history was positively associated with prevalent HIV among pregnant Thai women.57 Two studies reported on STI symptoms.24,40 In Russsia, unprotected sex with a partner with STI symptoms increased the likelihood of HIV among females but not males.24 Among Korean students, a symptomatic partner was unrelated to CT/GC.40

Discussion

Partner attributes are independently associated with STIs among male and female adolescents worldwide. Partner age, race/ethnicity, multiple sex partners and STI symptoms were assessed most frequently, across income settings and in relation to HIV and other STIs. Older partner age was examined in the greatest number of studies (n=27), including 8 of 12 prospective studies. Across settings, older age was associated with an increased likelihood of prevalent STIs in but was largely unrelated to incidence. The incidence studies enrolled STI-positive and -negative individuals, minimizing the possibility of lack of association due to differences among select at-risk populations. Perhaps differential access to care explains increased STI prevalence but not incidence among individuals with older partners. Further research is needed to elucidate mechanisms through which older partners increase STI prevalence and better understand partner age in relation to incidence. Currently, the evidence suggests that adolescents with older partners may have a differential need for STI testing and treatment but interventions aimed at reducing contact with older partners would likely not reduce incidence.

Black partner race was assessed in 11 of 12 studies which assessed race/ethnicity. The findings suggest that risk differs across participant race/ethnicity groups. While 10 of 11 studies reported significant associations, only 4 performed adjusted analyses,7,18,51,52 and only 2, both of which adjusted for participant race/ethnicity, reported significant adjusted associations.18,51 Aral et al reported that positive associations between an African-American partner and STIs were significant only for participants who were not themselves African-American. The one study conducted in a middle- or low-income setting reinforces the conclusion that risk associated with Black race is not uniform. Among Black men in the Caribbean, Black partner race was associated with decreased STI likelihood. These findings are consistent with studies suggesting that sexual mixing patterns influence STI transmission dynamics.71

Across income settings, partners with multiple sexual partners increased the likelihood of STIs predominantly among females. Of 15 cross-sectional studies, 6 of 9 which exclusively enrolled females reported significant findings.31,34,58,59,62,68 Of the 6 which included males,23,30,46,47,51 2 of 4 which did not stratify by gender found no association.23,30 Two which stratified by gender found that a partner with multiple partners significantly increased the likelihood of HIV among females only.46,47 The one study which exclusively enrolled males found no association between the number of partners’ other partners and the likelihood of GC.50

Similarly, a symptomatic partner may present risk predominantly for females, regardless of infection (HIV or other STI) and income setting. All 6 studies which explored a symptomatic partner in relation to CT among females reported significant positive associations. 15,35,55,58,59,68 Of the 2 studies which assessed a symptomatic partner in relation to CT/GC, 29,40 only 1 which exclusively enrolled females reported significant findings. 29,40Among males and females, a symptomatic partner was associated with increased HIV likelihood among females only.24

Some attributes were assessed only in one income setting in a limited number of studies but yielded consistent results. Sex with sex workers, tour guides, mineworkers and partners who travel were positively associated with HIV in middle- or low-income countries. Partner travel and periods away from home likely underlie the risk associated with sex with a tour guide or mineworker. All 6 studies, all conducted in high-income countries, reported that a partner with a known STI increased the likelihood of infection.

Partner attributes examined in both income settings and in relation to HIV and other STIs but not consistently associated with STIs included: education, gender, substance use, incarceration history and STI history. Attributes examined in a limited number studies in only 1 income setting with inconsistent results included: income, intimate partner violence, sex with a foreigner and sexual concurrency. Only four studies examined concurrency; despite theoretical evidence, empirical evidence regarding partner’s concurrency and STI risk among adolescents is lacking.

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of this review include the lack of standardized definitions of “partner” and partner attributes and lack of couple-based studies. In addition, we did not include all STIs in our review. Assessing the quality of each study was beyond our scope and represents another limitation. Future studies may consider evaluating studies based on sample selection, size and retention; control for individual behavior; laboratory methods, etc. Strengths include the use of biologically-confirmed STIs and the diversity of study samples and settings.

Implications for research

Although risk operates among couples and partner risk may be an equally, if not more, important determinant of risk as individual behavior,3,21,23,30,51 partner-level factors are less commonly assessed in STI research than individual characteristics and behaviors. Research among adolescents should further identify partner-level determinants of STI risk and mechanisms through which they act in order to improve prevention efforts.

Only one study assessed attributes reported by partners themselves. Additional couple-based studies are needed to extend the field’s current individual-focused framework and explore partner psychosocial factors and relationship characteristics that may be important to sexual risk. Better understanding of how relationship dynamics influence risk could be used to inform and develop new health behavior models as most fail to account for partner and relationship factors. As exemplified by studies exploring older partner age and STIs, longitudinal studies are important in overcoming biases present in cross-sectional studies. Further research on associations between partner and relationship characteristics and incident STIs may be important for developing and targeting interventions. Though difficult, future couple-based and longitudinal studies should take measures to limit the possibility of bias due to over-representation of individuals in more committed, stable and/or long-term relationships. Notably, only 1 reviewed study focused on MSM; additional research is needed to identify partner attributes associated with risk among this population.

Lastly, a standard “partner” definition would facilitate interpretation across studies. We propose that studies assess chronic infections (e.g., HIV) in relation to any of a participant’s lifetime partners. For other STIs, we propose the most recent sexual partner. However, in settings where a majority of participants are married or cohabitating, we propose the current main partner. Our proposal, while imperfect, aims to minimize data collection and recall error. Although insufficient evidence exists, last sexual partner may represent an adequate measure of partner selection over time, similar to condom use at last sex as a proxy measure for over time use.72 We acknowledge there will be compelling questions regarding other partners and that there may be more appropriate definitions for specific sub-populations. We encourage researchers to consider consensus regarding standard “partner” definitions.

Implications for prevention

These findings reinforce the importance of assessing partner attributes when determining STI risk. Although partner attributes are associated with STIs, we do not believe that interventions to influence partner selection based on these attributes are appropriate or likely to be effective. For example, Black partner race was associated with both incident and prevalent STIs, but risk varied across populations. Just as STI risk associated with Black partner race is not monolithic, Blacks do not have uniform risk,73 and, clearly, interventions influencing partner race would not be appropriate. Prevention efforts should continue to promote and address barriers to condom use. Efforts are needed to ensure adolescents with older, symptomatic and infected partners receive prompt testing and treatment. A number of studies reported increased STI risk among adolescents uncertain of their partner’s behavior, suggesting prevention efforts may benefit by improving adolescents’ sexual communication skills.

STI rates are higher among adolescent females, but males have more sexual risk behaviors.74 Our findings suggest that partner attributes may be a more important determinant of STI risk for females than males. Increased efforts are needed to screen, treat and reduce risky behavior among men.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement: Andrea Swartzendruber was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant number F32AA022058. Jennifer L. Brown was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant number K12 GM000680. Jessica M. Sales was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant number K01 MH085506.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributorship statement:

Jonathan M. Zenilman: Contributed substantially to conception and design, revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Linda M. Niccolai: Revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Trace S. Kershaw: Revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Jennifer L. Brown: Revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Ralph J. DiClemente: Revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Jessica M. Sales: Contributed substantially to conception and design, revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Disclosures: None reported

References

- 1.Dehne KL. Sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: The need for adequate health services. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Technische Zusammenarbeit; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. A review of STD/HIV preventive interventions for adolescents: Sustaining effects using an ecological approach. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(8):888–906. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson SR, Lavori PW, Brown NL, et al. Correlates of sexual risk for HIV infection in female members of heterosexual California Latino couples: An application of a Bernoulli process model. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(3):273–290. doi: 10.1023/a:1025495703560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, et al. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1630–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drumright LN, Gorbach PM, Holmes KK. Do people really know their sex partners? concurrency, knowledge of partner behavior, and sexually transmitted infections within partnerships. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(7):437–442. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000129949.30114.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer CB, Sebro NS, Wibbelsman C, et al. Acquisition of sexually transmitted infections in adolescents attending an urban, general HMO teen clinic. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnus M, Schillinger JA, Fortenberry JD, et al. Partner age not associated with recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis infection, condom use, or partner treatment and referral among adolescent women. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ickovics JR, Niccolai LM, Lewis JB, et al. High postpartum rates of sexually transmitted infections among teens: Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):469–473. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly RJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Age differences in sexual partners and risk of HIV-1 infection in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(4):446–451. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kissinger P, Clayton JL, O’Brien ME, et al. Older partners not associated with recurrence among female teenagers infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(3):144–149. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noell J, Rohde P, Ochs L, et al. Incidence and prevalence of chlamydia, herpes, and viral hepatitis in a homeless adolescent population. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(1):4–10. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittington WL, Kent C, Kissinger P, et al. Determinants of persistent and recurrent chlamydia trachomatis infection in young women: Results of a multicenter cohort study. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(2):117–123. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunnell RE, Dahlberg L, Rolfs R, et al. High prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in urban adolescent females despite moderate risk behaviors. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(5):1624–1631. doi: 10.1086/315080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillis SD, Coles FB, Litchfield B, et al. Doxycycline and azithromycin for prevention of chlamydial persistence or recurrence one month after treatment in women. A use-effectiveness study in public health settings. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosure DJ, Berman S, Kleinbaum D, et al. Predictors of chlamydia trachomatis infection among female adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ungchusak K, Rehle T, Thammapornpilap P, et al. Determinants of HIV infection among female commercial sex workers in northeastern Thailand: Results from a longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12(5):500–507. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199608150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulterys M, Chao A, Habimana P, et al. Incident HIV-1 infection in a cohort of young women in Butare, Rwanda. AIDS. 1994;8(11):1585–1591. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock EB, Manhart LE, Nelson SJ, et al. Comprehensive assessment of sociodemographic and behavioral risk factors for Mycoplasma genitalium infection in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(12):777–783. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e8087e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurt CB, Matthews DD, Calabria MS, et al. Sex with older partners is associated with primary HIV infection among men who have sex with men in North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(2):185–190. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c99114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munjoma MW, Mapingure MP, Stray-Pedersen B. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus type 2 and its association with HIV among pregnant teenagers in Zimbabwe. Sex Health. 2010;7(1):87–89. doi: 10.1071/SH09106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry PM, Kent CK, Klausner JD. Risk factors for gonorrhea among heterosexuals--San Francisco, 2006. 2009;36(2 Suppl):S62–S66. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815faab8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul KJ, Garcia PJ, Giesel AE, et al. Generation C: Prevalence of and risk factors for Chlamydia trachomatis among adolescents and young women in Lima, Peru. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(9):1419–1424. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staras SA, Cook RL, Clark DB. Sexual partner characteristics and sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents and young adults. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(4):232–238. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181901e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burchell AN, Calzavara LM, Orekhovsky V, et al. Characterization of an emerging heterosexual HIV epidemic in Russia. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(9):807–813. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181728a9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crosby RA, Diclemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Co-occurrence of intoxication during sex and sexually transmissible infections among young African American women: Does partner intoxication matter? Sex Health. 2008;5(3):285–289. doi: 10.1071/sh07098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scoular A, Abu-Rajab K, Winter A, et al. The case for social marketing in gonorrhoea prevention: Insights from sexual lifestyles in Glasgow genitourinary medicine clinic attendees. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(8):545–549. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein CR, Kaufman JS, Ford CA, et al. Partner age difference and prevalence of chlamydial infection among young adult women. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(5):447–452. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181659236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manhart LE, Holmes KK, Hughes JP, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium among young adults in the United States: An emerging sexually transmitted infection. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1118–1125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed JL, Mahabee-Gittens EM, Huppert JS. A decision rule to identify adolescent females with cervical infections. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(2):272–280. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auerswald CL, Muth SQ, Brown B, et al. Does partner selection contribute to sex differences in sexually transmitted infection rates among African American adolescents in San Francisco? Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(8):480–484. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204549.79603.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Pollack LM, et al. Sociodemographic markers and behavioral correlates of sexually transmitted infections in a nonclinical sample of adolescent and young adult women. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(3):307–315. doi: 10.1086/506328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-positivity in young, rural South African men. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(6):1455–1460. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-status in young rural South African women: Connections between intimate partner violence and HIV. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(6):1461–1468. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Msuya SE, Mbizvo E, Hussain A, et al. HIV among pregnant women in Moshi Tanzania: The role of sexual behavior, male partner characteristics and sexually transmitted infections. AIDS Res Ther. 2006;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Einwalter LA, Ritchie JM, Ault KA, et al. Gonorrhea and chlamydia infection among women visiting family planning clinics: Racial variation in prevalence and predictors. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):135–140. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.135.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettifor AE, Kleinschmidt I, Levin J, et al. A community-based study to examine the effect of a youth HIV prevention intervention on young people aged 15–24 in South Africa: Results of the baseline survey. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(10):971–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2005;19(14):1525–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000183129.16830.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jennings J, Glass B, Parham P, Adler N, Ellen JM. Sex partner concurrency, geographic context, and adolescent sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(12):734–739. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145850.12858.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagarde E, Congo Z, Meda N, et al. Epidemiology of HIV infection in urban Burkina Faso. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(6):395–402. doi: 10.1258/095646204774195254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SJ, Cho YH, Ha US, et al. Sexual behavior survey and screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in university students in South Korea. Int J Urol. 2005;12(2):187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettifor AE, Measham DM, Rees HV, Padian NS. Sexual power and HIV risk, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(11):1996–2004. doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]