Abstract

Objective

To evaluate labor progress and length according to maternal age.

Methods

Data were abstracted from the Consortium on Safe Labor, a multicenter retrospective study from 19 hospitals in the United States. We studied 120,442 laboring gravid women with singleton, term, cephalic fetuses with normal outcomes and without a prior cesarean delivery from 2002 to 2008. Maternal age categories were less than 20 years old, greater than or equal to 20 to less than 30, greater than or equal to 30 to less than 40 and greater than or 40 years old, with the reference being less than 20 years. Interval-censored regression analysis was used to determine median traverse times (progression cm by cm) with 95th percentiles, adjusting for covariates (race, admission body mass index, diabetes, gestational age, induction, augmentation, epidural use and birth weight). A repeated-measures analysis with an eighth-degree polynomial model was used to construct mean labor curves for each maternal age category, stratified by parity.

Results

Traverse times for nulliparous women demonstrated the time to progress from 4 to 10 cm decreased as age increased up to age 40 (median 8.5 hrs vs. 7.8 hrs in those greater than or equal to 20 to less than 30 year old group and 7.4 hrs in the greater than or equal to 30 to less than 40 year old group, p<0.001); the length of the second stage with and without epidural increased with age (p<0.001). For multiparous women, time to progress from 4 to 10 cm decreased as age increased (median 8.8 hrs, 7.5, 6.7 and 6.5 from the youngest to oldest maternal age groups, p<0.001). Labor progressed faster with increasing maternal age in both nulliparous and multiparous women in the labor curves analysis.

Conclusion

The first stage of labor progressed more quickly with increasing age for nulliparous up to age 40 and all multiparous women. Contemporary labor management should account for maternal age.

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Vital Statistics for 2011, the birth rate for older women, specifically those aged 35–39 and 40–44 years, has been steadily rising over the last several years (1). In parallel with this trend, the cesarean delivery rate has been consistently increasing as well (1). Numerous investigators have demonstrated that older women have higher rates of cesarean deliveries (2–5). The relationship between cesarean delivery and age is unclear but likely is influenced by other maternal and fetal factors. Women giving birth today are not the same as the cohort of women used to create the Friedman labor curves, which are often used today to identify normal versus abnormal labor progress (6–8). Based on more recently published literature, women today are older, heavier, vary in ethnicity and are more likely to undergo assisted reproduction (1, 9–10). They are also more likely to have a labor induction or augmentation and an epidural, and less likely to have an operative vaginal delivery (11–16). These factors may affect labor progress and may be partially responsible for the increasing cesarean rate (11–16). Furthermore, based on recent data, labor progress in a more contemporary population may be different than previously depicted in the Freidman curves (17–19).

Hence, as the obstetric population continues to change, a better understanding of the relationship between maternal age and labor progress is necessary. This may help to optimize labor and ultimately help reduce cesareans in the United States. The purpose of the current study is to characterize labor progress and length in women according to maternal age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis from the Consortium on Safe Labor database. The Consortium on Safe Labor is a collaboration among 12 geographically-dispersed clinical centers with 19 total participating community and academic hospitals. After data was collected at each center, it was transferred to a data collecting center where data inquiries, cleaning and logic checking was performed. Validation studies confirmed a high level of accuracy with greater than 95% concordance between the dataset and medical charts. Specifically, validation studies on four of the 20 outcomes examined (shoulder dystocia, cesarean delivery for non-reassuring fetal heart rate, neonatal intensive care unit admission for respiratory conditions, and neonatal asphyxia) were performed by hand-abstraction of eligible charts (20). The goal of the Consortium on Safe Labor was to construct a database from electronic medical records (EMRs) that would describe contemporary labor progression in the United States. There were 228,562 deliveries (87% of which occurred during 2005 through 2007) in the database. We included women with a known maternal age at delivery who had a singleton, live, term (≥37 weeks) birth in cephalic presentation. Women with prior cesarean deliveries were excluded. To avoid intraperson correlation, we selected the first delivery for each subject from the database. Abnormal neonatal outcomes, defined as 5-minute APGAR score less than 7, congenital anomalies, birth injury or neonatal intensive care unit admissions, were excluded to maintain consistency with the original study from the dataset (17). Women were grouped into four maternal age categories: less than 20 years old, greater than or equal to 20 to less than 30, greater than or equal to 30 to less than 40 and greater than or equal to 40 years old and then stratified by parity (i.e., nulliparous or multiparous). Demographics and maternal characteristics among the age categories were compared to the less than 20 year olds (referent) using Pearson χ2 and ANOVA tests.

To estimate the duration of labor, an interval-censored regression analysis was used to determine median traverse times with 95th percentiles, assuming the labor data had a normal distribution (21–22). The median traverse times represent the time to progress centimeter by centimeter, starting at 3 cm to complete dilation. Women with at least two cervical examinations, regardless of whether they reached 10 cm and irrespective of the ultimate delivery route, were included in the median traverse times analysis. The analysis was adjusted for covariates including race, admission body mass index (BMI), pre-existing diabetes, and gestational age at the time of admission, labor induction, labor augmentation, epidural use, and birth weight. The youngest age category (less than 20 years) within each parity cohort was selected as the referent for this statistical analysis. The median and 95th percentile times for the second stage of labor were also calculated for each maternal age category with and without epidural use and stratified by parity. Each age category was compared to the less than 20 year old category with generalized linear models, adjusting for race, admission BMI, pre-existing diabetes, gestational age at time of admission, labor induction, labor augmentation, birth weight and operative vaginal deliveries, and excluded woman who delivered by cesarean in the second stage. A p value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

A repeated-measures analysis with an eighth-degree polynomial model was used to construct mean labor curves by parity using cervical dilation in centimeters. The curves were constructed in a backwards fashion, where the starting point was set at the first time when dilation reached 10 centimeters (time = 0) and the time was calculated backwards (e.g. 60 minutes prior to complete dilation = −60 minutes). After the labor curve models had been completed, the x-axis (time) was reverted to a positive value (i.e. instead of −12 to 0 hours, it was transformed to 0 to 12 hours). The labor curves only included gravidas who reached 10 cm and had at least 2 cervical examinations and, did include those who may have had a cesarean in the second stage. The labor curves started at 3 cm so as to allow for convergence in an 8th degree polynomial model, but women who were admitted at earlier dilations also contributed data to the labor curves. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (PROC MIXED for the repeated-measures analysis and PROC LIFEREG for interval censored regression, PROC GLM for second stage of labor). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at all participating sites.

RESULTS

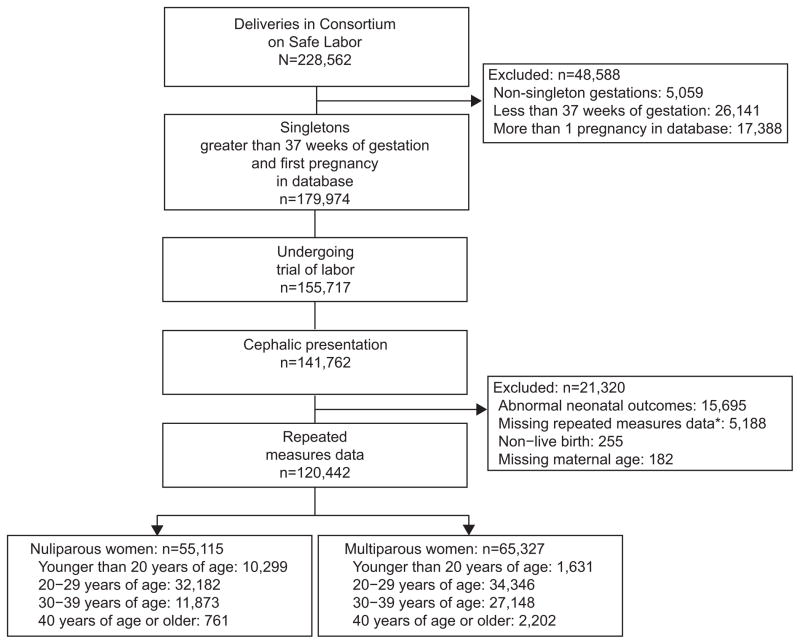

Of the 120,442 women who met inclusion criteria, 55,115 (45.8%) were nulliparous and 65,327 (54.2%) were multiparous (Figure 1). Among nulliparous and multiparous women, those who were aged less than 20 years were more likely to be of black race whereas those aged 20 years and greater were more likely to be of white race, p<0.001 (Table 1). As age increased, so did the incidence of pre-existing diabetes, labor inductions, epidural use, operative vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries in both parity groups, whereas admission dilation and effacement decreased, p<0.02. Operative vaginal deliveries included all vacuum and forceps-assisted deliveries.

Figure 1.

Participant eligibility. *Cervical dilation, effacement.

Table 1.

Maternal Demographics and Labor Characteristics by Maternal Age Group Stratified by Parity

| Characteristic | Maternal Age (y)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nulliparous Women (n=55,115) | Multiparous Women (n = 65,327) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Younger Than 20 (n= 10,299) | 20 or Older to Younger than 30 (n=32,182) | 30 or Older to Younger Than 40 (n= 11,873) | 40 or Older (n=761) | Younger Than 20 (n= 1,631) | 20 or Older to Younger Than 30 (n = 34,346) | 30 or Older to Younger Than 40 (n = 27,148) | 40 or Older (n=2,202) | |

| Admit BMI (kg/m2) | 30.1 ±5.8 | 30.3±6.0 | 29.8±5.5 | 29.5±5.5 | 30.1 ±5.8 | 30.7±6.0 | 30.6±5.7 | 30.5±5.4* |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 3,032 (31.0) | 17,785 (58.4) | 7,240 (63.7) | 485 (66.8) | 391 (25.0) | 17,105 (52.1) | 15,880 (61.0) | 1,179 (55.6) |

| Black | 3,921 (40.1) | 5,439 (17.9) | 1,207 (10.6) | 76 (10.5) | 676 (43.2) | 7,665 (23.3) | 3,936 (15.1) | 402 (18.9) |

| Hispanic | 2,439 (24.9) | 4,903 (16.1) | 1,470 (12.9) | 93 (12.8) | 446 (28.5) | 6,598 (20.1) | 4,237 (16.3) | 347 (16.4) |

| Other | 390 (4.0) | 2,317 (7.6) | 1,455 (12.8) | 72 (9.9) | 53 (3.4) | 1,472 (4.5) | 1,966 (7.6) | 194 (9.2) |

| Pre-existing diabetes | 45 (0.5) | 264 (0.9) | 224 (1.9) | 20 (2.7) | 8 (0.6) | 276 (0.9)* | 463 (1.8) | 56 (2.6) |

| Admit cervical dilation (cm) | 3.3±2.2 | 3.1±2.1 | 2.7±2.2 | 2.2 ±2.2 | 4.3 ±2.2 | 4.0±2.2 | 3.8±2.3 | 3.8±2.5 |

| Admit cervical effacement (%) | 76.0±24.3 | 76.1 ±23.0* | 73.6±25.5 | 68.4±28.5 | 76.5±21.7 | 74.7±21.5 | 73.8±22.3 | 72.8±24.8 |

| Labor augmentation | 1,868 (25.6) | 6,108 (23.7) | 2,148 (22.8) | 110 (18.3) | 258 (21.0) | 4,529 (16.5) | 3,740 (17.2) | 328 (19.6)* |

| Labor induction | 4,034 (40.3) | 13,716 (43.4) | 6,326 (54.3) | 479 (63.6) | 438 (27.6) | 13,134 (38.9) | 11,429 (42.7) | 1,014 (46.7) |

| Epidural use | 4,624 (56.0) | 17,410 (63.3) | 7,037 (69.0) | 482 (71.9) | 632 (46.6) | 16,114 (56.1) | 13,706 (60.3) | 1,058 (58.2) |

| Admit gestational age (wk) | 39.4±1.2 | 39.4±1.1* | 39.5±1.1 | 39.4±1.2* | 39.3±1.2 | 39.2±1.1 | 39.2±1.1 | 39.2±1.1 |

| Neonatal birth weight (g) | 3,239±417 | 3,335±427 | 3,375±436 | 3,363±440 | 3,274 ±397 | 3,370±428 | 3,437±437 | 3,438±464 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 249 (2.4) | 1,091 (3.4) | 803 (6.8) | 68 (8.9) | 13 (0.8) | 226 (0.7)* | 210 (0.8)* | 21 (1.0)* |

| Delivery route | ||||||||

| Cesarean | 1,592 (15.5) | 6,028 (18.7) | 3,483 (29.3) | 339 (44.6) | 90 (5.5) | 1,832 (5.3)* | 1,953 (7.2) | 271 (12.3) |

| Vaginal | 8,707 (84.5) | 26,154 (81.3) | 8,390 (70.7) | 422 (55.4) | 1,541 (94.5) | 32,514 (94.7)* | 25,195 (92.8) | 1,931 (87.7) |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 828 (7.7) | 3,464 (10.8) | 1,309 (11.0) | 81 (10.6) | 40 (2.5) | 1,130 (3.3)* | 1,108 (4.1) | 113 (5.1) |

BMI, body mass index.

Data are mean± standard deviation or n (%).

Not significant; otherwise, all P<.001 for the comparison of each age group to those aged younger than 20 years (referent).

For nulliparous women, time to progress centimeter to centimeter decreased as age increased in up to 40 years old (Table 2). The time to progress from 4 to 10 cm decreased as age increased up to 40 years old, with nulliparous women less than 20 years old progressing the slowest (median 8.5 hours vs. 7.8 hours in those greater than or equal to 20 to less than 30 year old group and 7.4 hours in the greater than or equal to 30 to less than 40 year old group, p<0.001). Those greater than or equal to 40 years old took 8.0 hours to progress from 4 to 10 cm; however this did not differ compared to the referent group, p>0.05. The second stage of labor with and without an epidural increased directly with age (p<0.001), and epidural use was associated in an increase in the duration of second stage by approximately 0.4 hours in all age groups.

Table 2.

Labor Duration in Nulliparous Women by Maternal Age Group

| Cervical Dilation (cm) | Maternal Age (y)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Younger Than 20 | 20 or Older to Younger Than 30 | 30 or Older to Younger Than 40 | 40 or Older | |

| 3–4 | 5.1 (11.0) | 4.4 (9.7) | 4.0 (8.9) | 3.4 (7.4) |

| 4–5 | 3.6 (8.7) | 3.1 (7.4) | 2.8 (6.5) | 3.2 (7.3)* |

| 5–6 | 2.2 (5.4) | 2.1 (5.2) | 1.9 (4.3) | 2.4 (5.7) |

| 6–7 | 1.6 (3.7) | 1.5 (3.6)* | 1.5(3.4) | 1.5 (3.1) |

| 7–8 | 1.3 (3.1) | 1.2 (2.7) | 1.2 (2.6) | 1.4 (3.0) |

| 8–9 | 1.1 (2.4) | 1.1 (2.4)* | 1.2 (2.4) | 1.1 (2.2) |

| 9–10 | 1.1 (2.3) | 1.1 (2.4) | 1.2 (2.6) | 1.1 (2.1) |

| 4–10 | 8.5 (17.2) | 7.8 (16.1) | 7.4 (15.1) | 8.0 (16.9)* |

| 2nd stage with epidural | 1.0 (3.1) | 1.2 (3.4) | 1.5 (4.3) | 1.5 (5.2) |

| 2nd stage without epidural | 0.6 (2.3) | 0.8 (2.7) | 1.0 (3.5) | 1.1 (4.1) |

Data are median traverse time (95th percentile). First and second stage of labor reported as median traverse times in hours (95th percentile).

Not significant; otherwise, all P<.03 for the comparison of each age group to those aged younger than 20 y (referent).

First stage was adjusted for race, admission body mass index, pre-existing diabetes, gestational age at time of admission, labor induction, labor augmentation and birth weight. Second stage was adjusted for the same covariates as well as operative vaginal deliveries and excluded cesarean deliveries that occurred in the second stage.

According to the median traverse times, multiparous women progressed through labor faster as age increased (Table 3). The time to traverse from 4–10 cm was 8.8 hours and 6.5 hours for the youngest and oldest groups, respectively. The second stage of labor with and without an epidural was not different among age groups and epidural use was associated with an increase the length of second stage by 0.2 hours in all groups.

Table 3.

Labor Duration in Multiparous Women by Maternal Age Group

| Cervical Dilation (cm) | Maternal Age (y)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Younger Than 20 | 20 or Older to Younger Than 30 | 30 or Older to Younger Than 40 | 40 or Older | |

| 3–4 | 5.8 (11.5) | 5.4 (11.2) | 4.7 (9.9) | 4.4 (9.5) |

| 4–5 | 3.9 (8.7) | 3.3 (7.4) | 2.8 (6.6) | 2.7 (6.2) |

| 5–6 | 2.0 (4.5) | 2.0 (4.9) | 1.8 (4.7) | 1.8 (4.6) |

| 6–7 | 1.6 (4.3) | 1.4 (3.6) | 1.3 (3.5) | 1.4 (3.9) |

| 7–8 | 1.0 (2.4) | 1.0 (2.7) | 1.0 (2.6) | 0.8 (1.8) |

| 8–9 | 0.9 (2.3) | 0.9 (2.4) | 0.8 (2.2) | 0.8 (2.1) |

| 9–10 | 0.9 (2.4) | 0.8 (2.1) | 0.8 (2.1) | 0.6 (1.4) |

| 4–10 | 8.8 (17.6) | 7.5 (15.7) | 6.7 (14.5) | 6.5 (14.1) |

| 2nd stage with epidural | 0.4 (1.8) | 0.4 (1.5)* | 0.4 (1.7)* | 0.4 (2.3) |

| 2nd stage without epidural | 0.2 (1.0) | 0.2 (1.0)* | 0.2 (1.1)* | 0.2 (1.3)* |

Data are median traverse firm: (95th percentile). First and second stage of labor reported as median traverse times in hours (95th percentile).

First stage of labor was adjusted for race, admission body mass index, pre-existing diabetes, gestational age at time of admission, labor induction, labor augmentation, and birth weight. Second stage was adjusted for the same covariates as well as operative vaginal deliveries and excluded cesarean deliveries in the second stage.

Not significant; otherwise, all P< .001 for the comparison of each age group to those aged younger than 20 y (referent).

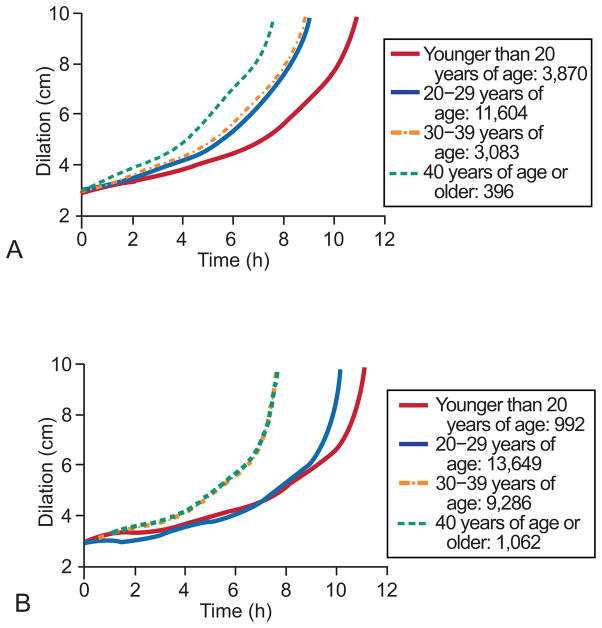

Figure 2 demonstrates the mean labor curves for nulliparous women (n = 18,953, Figure 2A) and multiparous women (n = 24,989, Figure 2B) who reached 10 cm dilation by each maternal age category. For both nulliparous and multiparous women, those less than 20 years old progressed through labor the slowest. In nulliparous women, those less than 20 and those 40 years and greater progressed through labor at markedly different rates, while the two middle age categories progressed at similar rates (Figure 2A). In contrast, the labor curves for multiparous women demonstrated that women less than 20 years old and those women greater than 20 years old but less than 30 years old progressed through labor at similar rates and slower than the two oldest age categories which is in agreement with the median traverse times (Figure 2B). In nulliparous women there was no apparent inflection point, whereas the multiparous women had an inflection point around 6 cm, after which the rate of cervical change increases markedly.

Figure 2.

Mean labor curves for nulliparous women (A) and multiparous women (B) who reached 10 cm dilation by each maternal age category.

DISCUSSION

We initially hypothesized that the first stage of labor would progress more slowly as maternal age increased. Instead, we demonstrated that the first stage of labor progressed more quickly with increasing maternal age as reflected by the median traverse times, especially in multiparous women, and by the labor curves in both nulliparous and multiparous women. These findings are independent of important covariates such as labor induction or augmentation. The labor curves suggest a difference in labor patterns between the youngest and oldest parturients for both nulliparous and multiparous women. All these findings are especially important for clinical practice because the cohort of parturients studied represents a contemporary group of women.

Our median traverse times and total labor lengths are in agreement with the original studies by Friedman (6, 23). We have additionally found a relationship between maternal age and labor progression seen in our labor curves that has not been previously demonstrated. In 1965, Friedman and Sachtleben evaluated labor length in 3,329 nulliparous women and found no important difference in the course of labor that could be ascribed to maternal age when comparing the young (less than 18 years old) and the older (greater than 35 years old) parturient (8). However, the authors note that their study may not have been powered to find a significant difference. In their analysis of 26 control-matched gravidas, Sokol et al concluded advanced maternal age was not associated with labor prolongation (24). With respect to the second stage length, our findings agree with other studies in that second stage increases directly with age with and without an epidural (6–8, 25–26).

Greenberg et al assessed how maternal age affects the first and second stage labor lengths as a whole (27). In their analysis of 31,976 births, they concluded that nulliparous women had increasing median lengths of labor as age increased, but this pattern was only present up to 34 years, after which the length of labor decreased in the 35–39 and ≥40 year old groups. Furthermore, younger women had a slightly longer first stage than older women (6.1 hours in those less than 20 years and 5.7 hours in those greater than 40 years, p = 0.02). This bimodal distribution in which first stage labor length is similar among the youngest and oldest group according to the traverse times is similar to our work and warrants more investigation as it differs from the trend in our labor curves. Because the difference in first stage labor length was so small among the groups, they concluded that clinical applicability may be limited to the 95th percentile values only (27). In terms of the second stage, their findings were in agreement with ours (27).

Our study is not without limitations. The labor curves for older women (mainly those 40 years and older) may not represent true labor if a woman delivered by cesarean prior to achieving complete dilation, possibly due to physicians’ preferences because these women wound not be included in the labor curves. However, Adashek et al found that increasing maternal age was independently associated with increased CD rates, but did not find any controllable physician factors for this association (4). There were statistically significant differences in most maternal and labor characteristics among the age groups due to the large sample size of our study (Table 1), yet this may be of limited clinical significance. The subjectivity of cervical examinations must be considered as well as the lack of uniform labor protocols among all the institutions that participated in the Consortium on Safe Labor. To assess true spontaneous labor, we attempted to perform a secondary analysis excluding all parturients who received augmentation or induction agents. Because labor augmentation and induction were relatively common in our study cohort, averaging approximately 60%, this analysis was not feasible due to a much smaller sample size. Harper et al demonstrated that induced labor progresses strikingly slower than spontaneous labor (28). Therefore, our estimates of labor length are likely conservative. Including all women who were augmented or induced may be considered a strength of our study design in that it allows for accurate representation of a more contemporary obstetric cohort, compared to prior reports that focused only on spontaneous labor. The effect of maternal age on spontaneous versus augmented or induced labor warrants further study, for which we lacked an adequate sample size to assess.

The strengths of our work include being a multicenter cohort study, generalizable to women across the United States. Our aim was to assist practitioners in understanding the influence of maternal age on labor progress. Further research to assess the physiologic aging process on myometrial tissues is also needed. In general, our findings confirm the need for a better understanding of the mechanism underlying uterine contractility as well as the effect of age on uterine musculature. Given that maternal age influences the first and second stage of labor in opposite directions according to our findings, we speculate that there is likely a very fundamental difference in the aging process of smooth versus striated muscle.

Based on our analysis, we conclude that contemporary labor practices should take in to account the changing age profiles of obstetric populations in the United States. Our findings suggest that younger women progress through labor at a slower rate and older women progress faster. We therefore recommend that maternal age be taken into consideration prior to intervening with cesarean delivery. This is especially true for young nulliparous women in whom delivery route may have a major effect on future pregnancy outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Supported by:

Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (M.A.K, J.H.), through a contract (Contract No. HHSN267200603425C), Grant Number K12HD055892 from the NICHD and NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (M.A.K.).

University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS), Award Number UL1RR029879 from the National Center For Research Resources.

Appendix

Institutions involved in the Consortium include, in alphabetical order: Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Burnes Allen Research Center, Los Angeles, CA; Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE; Georgetown University Hospital, MedStar Health, Washington, DC; Indiana University Clarian Health, Indianapolis, IN; Intermountain Healthcare and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY; MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.; Summa Health System, Akron City Hospital, Akron, OH; The EMMES Corporation, Rockville MD (Data Coordinating Center); University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; University of Miami, Miami, FL; and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas.

Footnotes

For a list of institutions involved in the Consortium on Safe Labor, see the Appendix online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, which does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the NICHD.

Presented as a poster at the Society for Gynecologic Investigation 59th Annual Scientific Meeting; San Diego, California; March 21–24, 2012.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ecker JL, Chen KT, Cohen AP, Riley LE, Lieberman ES. Increased risk of cesarean delivery with advancing maternal age: indications and associated factors in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:883–887. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Main DM, Main EK, Moore DH. The relationship between maternal age and uterine dysfunction: a continuous effect throughout reproductive life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1312–1320. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adashek JA, Peaceman AM, Lopez-Zeno JA, Minogue JP, Socol ML. Factors contributing to the increased cesarean birth rate in older parturient women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:936–940. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90030-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heffner LJ, Elkin E, Fretts RC. Impact of labor induction, gestational age, and maternal age on cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman EA. The graphic analysis of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68:1568–75. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(54)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphico-statistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:567–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman EA, Sachtleben MR. Relation of maternal age to the course of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;91:915–924. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(65)90555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preston SH, Hartness SC. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 14498. 2008. The Future of American Fertility. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MB, Cheng YW, Hopkins LM, Stotland NE, Bryant AS, Caughey AB. Are there ethnic differences in the length of labor? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:743–748. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vahratian A, Zhang J, Troendle JF, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM. Maternal prepregnancy overweight and obesity and the pattern of labor progression in term nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:943–951. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000142713.53197.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergholt T, Lim LK, Jorgensen JS, Robson MS. Maternal body mass index in the first trimester and risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous women in spontaneous labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:163.e1–163.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caughey AB, Nicholson JM, Cheng YW, Lyell DJ, Washington AE. Induction of labor and cesarean delivery by gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner MJ, Rasmussen MJ, Turner JE, Boylan PC, MacDonald D, Stronge JM. The influence of birth weight on labor in nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kominiarek MA, Zhang J, VanVeldhuisen P, Troendle J, Beaver J, Hibbard JU. Contemporary labor patterns: the impact of maternal body mass index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:244e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Landy HJ, Branch DW, Burkman R, Haberman S, Gregory KD, et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1281–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinehart BK, Terrone DA, Hudson C, Esler CM, Larmon JE, Perry KG. Lack of utility of standard labor curves in the prediction of progression during labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1520–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Impey L, Hobson J, O’Herlihy C. Graphic analysis of actively managed labor: Prospective computation of labor progress in 5000 consecutive nulliparous women in spontaneous labor at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:438–43. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Branch DW, Burkman R, et al. for the Consortium on Safe Labor. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:326.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data. Berlin: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vahratian A, Troendle JF, Siega-Riz AM, Zhang J. Methodological Challenges in studying labour progression. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:27–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman EA. Evolution of graphic analysis of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;132(7):824–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(78)80018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sokol RJ, Walker R, Nassbaum R, Rosen MG, Chik LC. Computer Diagnosis of labor progression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;122(2):253–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papadias K, Christopoulos P, Deligeoroglou E, Vitoratos N, Makrakis E, Kaltapanidou P. Maternal Age and the Duration of the Second Stage of Labor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992:414–417. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterson CM, Saunders NS, Wadsworth J. The characteristics of the second stage of labor in 25,069 singleton deliveries in the North West Thames Health Region, 1988. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99(5):377–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberg MB, Cheng YW, Sullivan M, Norton ME, Hopkins LM, Caughey AB. Does length of labor vary by maternal age? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:428.e1–428.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper LM, Caughey AB, Odibo AO, Roehl KA, Zhao Q, Cahill AG. Normal progress of induced labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;199:1113–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318253d7aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]