Abstract

Gene therapy is suggested as a promising alternative strategy of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, also called hepatoma) therapy. To achieve a successful and safe gene therapy, tight regulation of gene expression is required to minimize side-effects in normal tissues. In this study, we developed a novel hypoxia and hepatoma dual specific gene expression vector. The constructed vectors were transfected into various cell lines using bio-reducible polymer, PAM-ABP. First, pAFPS-Luc or pAFPL-Luc vector was constructed with the alpha-fectoprotein (AFP) promoter and enhancer for hepatoma tissue specific gene expression. Then, pEpo-AFPL-Luc was constructed by insertion of the erythropoietin (Epo) enhancer for hypoxic cancer specific gene expression. In vitro transfection assay showed that pEpo-AFPL-Luc transfected hepatoma cell increased gene expression under hypoxic condition. To confirm the therapeutic effect of dual specific vector, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene (HSV-TK) was introduced for cancer cell killing. The pEpo-AFPL-TK was transfected into hepatoma cell lines in the presence of ganciclovir (GCV) pro-drug. Caspase-3/7, MTT and TUNEL assays elucidated that pEpo-AFPL-TK transfected cells showed significant increasing of death rate in hypoxic hepatoma cells compared to controls. Therefore, the hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression vector with the the Epo enhancer and AFP promoter may be useful for hepatoma specific gene therapy.

Keywords: Hepatoma, gene regulation, suicide gene therapy, bio-reducible polymer, cancer hypoxia

1. Introduction

Hepatoma is the most common type of a primary cancer of the liver which is mainly caused by viral hepatitis infection or liver cirrhosis. Currently, liver transplantation and conventional treatments such as surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are counted as the best treatment options of hepatoma. However, the current therapies can apply only early stages of cancer cells, due to the chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis [1, 2]. Moreover, recurrence of tumor after the surgical treatment also brings down survival rates of the patients [3, 4]. For these reasons, hepatoma remains one of the most difficult tumors to cure. In order to overcome the limitation of current therapy methods, gene therapy has been suggested as a potential novel approach for hepatoma.

Suicide gene therapy is based on the introduction of a gene into tumor cells with pro-drug. Recently, Herpes Simplex Virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) gene and cytosine deaminase (CD) gene are widely used for suicide genes. In HSV-TK and ganciclovir (GCV) pro-drug (TK/GCV) system, the TK gene is delivered and expressed in tumor cells, converting to the administrated GCV pro-drug into toxic phosphorylated form. The GCV inhibits DNA synthesis, resulting in killing of dividing cancer cells. In addition, the cancer cells are coupled by gap junctions, which enhance the cancer cell killing by the transfer of toxic GCV to neighboring cancer cells do not express TK. This phenomenon was known as the “bystander effect” [5]. Therefore, the TK/GCV gene therapy is one of the powerful strategies for cancer gene therapy.

Although the prospective results were observed in many researches, further strategies are required to overcome the problems of current gene therapy such as toxicity and non-specific death of normal tissues [6]. Most of all, controllable therapeutic gene is an important factor to avoid side-effects in normal tissues [7]. For this purpose, several tissue-specific promoters have been developed and alpha-fectoprotein (AFP) gene promoter is being used for hepatoma targeting gene expression [8, 9]. AFP is a main plasma protein of mammalian fetal serum, and produced during fetal development and immediately decreased after birth. Although, normally AFP gene is silent in adult liver, most of hepatoma cells re-express it and produce abundant amount of AFP. Because of this feature, increasing the levels of AFP in blood is widely used as an important marker for hepatoma diagnosis [10].

Fibrogenesis of hepatoma chronic injury causes damaged blood system, which leads to the low blood supply to the liver and consequently leads to hypoxia. The hypoxic regions of hepatoma also induce high proliferation of tumor cells by expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This dual-aspect of hypoxia in hepatoma suggests that hypoxia regions are the critical targeting feature for hepatoma gene therapy [11]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the combination of regulatory elements for hepatoma tissues and cancer hypoxia may be useful for maximum gene expression with high specificity to hepatoma.

Additionally, delivery carrier is one part of non-viral gene therapy system along with therapeutic gene expression vector. Currently, more than 70% of approved clinical trials have used viral vectors for gene therapy [12]. Viral vectors have the high gene delivery efficiency, whereas they have the problems such as immunogenicity and safety. For these reasons, development of non-viral vectors was promoted as an alternative gene delivery carrier. Previously, an arginine-grafted poly (cystaminebisacrylamide-diaminohexane) (ABP) polymer was developed by our group. Because of the disulfide bonds, ABP can be biodegraded in the intracellular cytoplasm. The ABP showed higher transfection efficiency in comparison with polyethylenimine (25 kDa, PEI25K) with insignificant cytotoxicity[13]. Recently, to improve the ABP efficiency, new modified dendrimer type poly(amido amine) (PAMAM) conjugated ABP named “PAM-ABP” was developed[14].

In this study, a novel hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression vectors, pEpo-AFPL-Luc and pEpo-AFPL-TK were constructed and delivered by bio-reducible non-toxic polymer, PAM-ABP. The transfection and gene expression efficiency of PAM-ABP/pEpo-AFPL-Luc system was evaluated by luciferase assay. In addition, therapeutic effect of dual specific vector was verified using TK gene for hepatoma gene therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polyethylenimine (branched, 25 kDa, PEI), heparin and 3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Lipofectamine, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS), phosphate-buffered saline(PBS), lipofectamine 2000, gel extraction kit, total RNA isolation kit, high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit with RNA inhibitor, DNA purification kit and Pfx DNA Polymerase were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). BCA assay kit was purchased from pierce (Rocford,IL). Luciferase assay kit, 5x reporter lysis buffer, agarose, restriction enzymes, Caspase-Glo® 3/7 assay kit and DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Huh7 and HepG2 human hepatoma, 293 human embryonic kidney and A549 human lung cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). PAMABP was previously synthesis [14].

2.2. Plasmid construction

pSV-Luc was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Cloning of the promoters was performed by PCR. An expression vector containing the human alpha-fectoproten promoter and enhancer, pDRIVE5s-AFP-hAFP, purchased from invivogen (San Diego, CA) and was used as a PCR template. The fragments coding include 0.3 kbp and AFP promoter (AFPS) 0.7 kbp AFP enhancer regulatory region with promoter (AFPL) were amplified by PCR using Pfx DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad,CA). The sequences of the primers were as follows: AFPL promoter; forward5’- CCG CTC GAG ATG ATT CCC AAA TGT CTA TCT CTA-3’, backward 5’-CCC AAGCTT GGT TGC TAG TTA TTT TGT TAT TG -3’. AFPS promoter; forward 5’- CCG CTC GAG GTT TGA GGA GAA TAT TTG TTA T -3’, backward5’- CCC AAGCTT GGT TGC TAG TTA TTT TGT TAT TG -3’. For cloning convenience, the XhoI and Hind III sites were introduced to forward and backward primers as underlined. Purified promoters were inserted at the XhoI and Hind III site of pSV-Luc, which produced pAFPL-Luc or pAFPS-Luc, respectively. pEpo-SV-Luc was constructed previously [15]. The Epo enhancer was amplified by PCR. For cloning convenience, the NheI site was introduced to the primers. The sequences of the primers were as follows: forward (or backward)5’- CTA GCT AGC GCG GAG TTA GGG GCG GGA TGG-3’, The amplified Epo enhancer was inserted into the upstream of the AFPL promoter, produced pEpo-AFPL-Luc. pSV-TK was constructed previously [16]. pEpo-AFPL-TK was constructed by the insertion of the TK gene at the place of the luciferase gene of the pAFPL-Luc. The resulting vectors, pAFPL-Luc, pAFPS-Luc, pEpo-AFPL-Luc and pEpo-AFPL-TK were confirmed by restriction enzyme study and direct sequencing.

2.3. Complexes preparation

PAM-ABP and plasmid DNAs (pDNAs) complexes were prepared at a various weight ratios by mixing fixed amount of pDNAs (1μg/well) in PBS. PEI25K/pDNA or lipofectamine/pDNA complexes were prepared at a 1:1 or 2.5:1 weight ratio in PBS, respectively. The volume of mixture was fixed at 50μl/well. The mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature for complex formation. After incubation, the complexes were treated into each well.

2.4. Measurement of zeta-potential and complex size

PAM-ABP (1μg/μl) and pAFPL-Luc (1μg/μl) complexes were prepared at 1:1, 3, 5 and 7 weight ratios. PAM-ABP and fixed amount of pAFPL-Luc (2μg) was mixed in 100 μl PBS. After the 30 min incubation at room temperature, the complexes were dissolved in 700 μl H2O and then particle sizes and zeta potentials were determined by the Zetasizer Nano ZSsystem (Malvern Instruments, UK).The size and zeta-potential were presented as the average values from 5 runs.

2.5. Gel retardation assay

PAM-ABP/pAFPL-Luc complexes were prepared at various weight ratios by mixing fixed amount of pAFPL-Luc (0.5 μg) with increasing amounts of PAM-ABP (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) in PBS. After 30 min incubation, the samples were electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel containing SYBR gel staining solution for 40 min.

2.6. Serum stability assay

PAM-ABP/pAFPL-Luc or PEI25K/pAFPL-Luc complexes were prepared at a 5:1 or 1:1 weight ratio in PBS and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation, fetal bovine serum was added to the complexes at a 50% final concentration. Complexes were incubated in 37 °C shaking incubator for 0, 30, 60 and 90 min. To dissociate the pDNA from complexes, same volume of 600× heparin solution was added in to the complex mixture for 300× final concentration in the presence of 0.01 mol/l EDTA. After 60 min of incubation with heparin, the complexes were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis [17].

2.7. Cell culture and transfection

Huh7 and HepG2 human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cells, A549 human lung cancer cell line and 293T human embryonic kidney cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For the transfection assays, the cells were seeded at a density of 1.0×105 cells/well in 12-well plates (Greiner Bio-one, NC). After 24hrs incubation, media was replaced with fresh DMEM and then, the carrier/pDNA complexes were added to the each well. After 4hrs incubation, fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS and with or without GCV (100μg/ml) was replaced. The cells were incubated for an additional 48 hrs under normoxia (20% oxygen) or hypoxia (1% oxygen) condition.

2.8. In vitro luciferase assay

After the incubation, the cells were washed twice with DPBS and 150 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to each well. The lysates were harvested and centrifuged. The protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Luciferase activity was measured in terms of relative light units (RLU) using a luminometer (Infinite M2000; Tecan Inc., Mannedorf, Switzerland). The final values of luciferases were reported in terms of RLU/mg total protein.

2.9. MTT assay

Cell cytotoxicy of complexes and viability of the TK transfected cells were measured by MTT assay. Transfection into Huh7 cells was performed as described above. The end of the incubation, 20 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) solution in 1×PBS was added to each well. Cells were incubated for additional 4 hrs at 37 °C. The MTT-containing medium was removed and 500 μl of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals formed by the live cells. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm and cell viability (%) was calculated according to relative value.

2.10. RT-PCR

pSV-Luc, pSV-TK and pEpo-AFPL-TK were transfected into Huh7 cells and incubated under normoxia or hypoixa as described above. After the incubation, total RNA was extracted by total RNA isolation kit. The total RNA (1 μg) was hybridized to the backward primer and reverse-transcribed using cDNA reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) . The reverse transcribed samples were amplified by PCR using Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).The sequences of PCR primers were as follows 5′-TK gene: 5’-ATCATTCCGGATACTGCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTCTAGACACGGCGATCTTTC-3′ (backward); β-actin: 5’-CTGGGACGACATGGAGAAAA-3’ (forward) 5’-AAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAGTGC-3’ (backward). For the estimation of RT-PCR quantification, electrophoretic gel was analyzed by densitometry using an image J program (NIH image).

2.11. Caspase-3/7 assay

To determine apoptosis induction, caspase-3/7 measured by Caspase-Glo® 3/7 assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). For the transfection, the Huh7 cells were seeded at a density of 1.0×104 cells/well in 96-well white plates and incubated for 24 hrs. Before the transfection, media was replaced with fresh DMEM and then the carrier/pDNA complexes were added to the each well. The amount of plasmid DNA was fixed 0.5 μg/well. After 4hrs incubation, fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS and GCV was replaced. After 24hrs and 48hrs of incubation under normoxia or hypoxia condition, caspase-3/7 assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.12. TUNEL assay

In vitro apoptosis assay was measured by DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System (Promega, Madison, WI). For the transfection, the Huh7 cells were seeded at a density of 5.0×104 cells/well in 4well Lab-Tek® Chamber Slide. The transfection was performed as described above the assay section. After 48hrs of incubation with GCV, TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. For quantitative results, the TUNEL positive cells were counting in five random area images for each sample by Image J program. The stained cells were examined under fluorescence microscope.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between two groups were made using Student's t-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of hepatoma specific gene expression plasmid and in vitro transfection

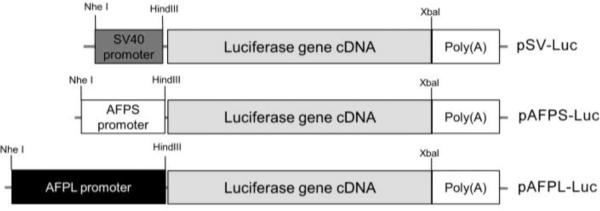

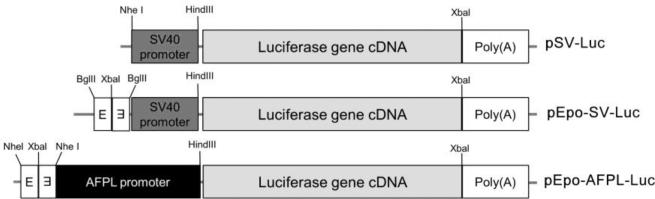

For hepatoma specific gene expression, we constructed pAFPS-Luc containing AFP promoter and pAFPL-Luc containing AFP promoter with enhancer regulatory regions. (Fig. 1). The construction of plasmids was performed as described in the materials and methods section.

Figure 1. Construction of hepatoma specific gene expression plasmids.

The structure of the luciferase reporter gene constructs containing the SV40 promoter, AFPS promoter or AFPL promoter.

3.2. Characterization of PAM-ABP/pDNA complexes

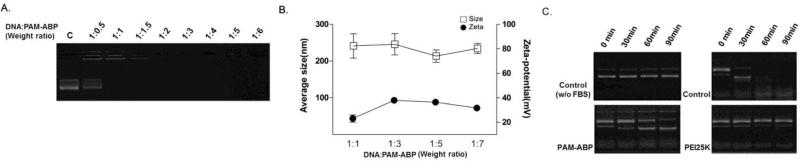

In order to use of PAM-ABP as a gene carrier into hepatoma cells, physical characterizations of the PAM-ABP/pDNA complex were performed. pAFPL-Luc was used as a pDNA for complex formation. To confirm the complex formation between PAM-ABP and pDNA, a gel retardation assay was performed. A fixed amount of pDNA (0.5 μg/ul) was mixed with increasing amount of PAM-ABP. In Figure 2A, the DNA band disappeared from 1:1 ratio (PAM-ABP: pDNA weight ratio) and completely retarded above 2: 1 weight ratio. The average mean diameter of the complex was approximately 100 nm and the zeta potential showed a positive charge with an average of 30 mV (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that the PAMABP can form compact complex with the constructed pDNA.

Figure 2. Physical characterization of PAM-ABP/pDNA complex.

(A) Gel retardation assay. PAM-ABP/pDNA complexes were prepared at various weight ratios and analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. (B) Particle size and zeta potential. PAM-ABP/pDNA complexes were measured at various weight ratios. Data are expressed as mean values (±standard deviation) of triplicate experiments. (C) Serum stability assay. Carrier/pDNA complexes were incubated with 50% FBS and naked pDNA was incubated with or without 50% FBS under shaking at 37 °C for 0, 30, 60 and 90 min. After incubation, DNA was analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis

An extracellular barrier including blood is the first obstacle of gene delivery into the cells of interest. When the naked DNA delivered directly into the body, it can be easily digested by nucleases in serum. Therefore, stability of the carrier/pDNA complex is important parameter. For efficient gene delivery, pDNA should be protected by delivery carriers against of nucleases degradation. For this reason, the pDNA protection ability of PAM-ABP was evaluated by serum stability assay. The PAM-ABP/pDNA complex was prepared at a 5:1 weight ratio, which has the highest transfection efficiency into hepatoma cells (Fig. 4A). Naked pDNA (with or without FBS) and the PEI25K/pDNA complex (1:1 weight ratio ratio) were used as controls. The complexes were incubated with 50% FBS under shaking at 37°C for 0, 30, 60 and 90 min. Naked DNA showed degraded DNA fragments from 30 min and completely degraded in 60 min incubation. In contrast, PEI25k/pDNA complex or without FBS group showed intact DNA until 90 min. The PAM-ABP/pDNA complex had protected pDNA for more than 60 min and some intact DNA remained after incubation for over 90 min. The results suggested that PAM-ABP formed stable complexes with pDNA and it can be protect efficiently the pDNA from degradation by serum (Fig. 2C).

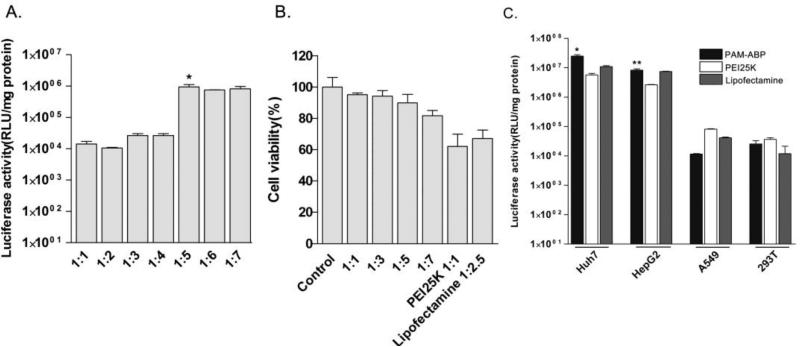

Figure 4. Transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity of PAM-ABP.

(A) Transfection efficiency and (B) Cytotoxicity of PAM-ABP based on weight ratio. (C) Comparison of transfection efficiency. Carriers/pAFPL-Luc complexes were transfected into Huh 7 cells as fallows conditions: PAM-ABP; 5:1 weight ratio, PEI25K; 1:1 weight ratio and lipofectamine; 2.5:1 weight ratio. Control indicates non-transfected Huh7 cells. After 48 hrs, transfection efficiency was measured by luciferase assay. The data are expressed as mean values (±standard deviation) of quadruplicate experiments *P<0.05 as compared withPEI25Kand lipofectamine. **P<0.05 as compared with PEI25K.

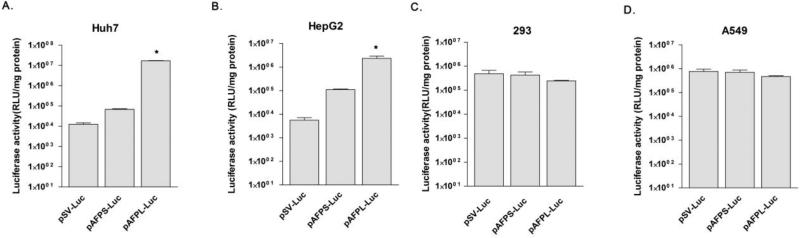

3.3. Hepatoma specific promoter activity in various cell lines

In vitro transfection assay was performed to evaluate and compare the hepatoma targeting promoter activity of pAFPS-Luc or pAFPL-Luc. The pDNAs were transfected into Huh7 and HepG2 human hepatoma cells, 293 human embryonic kidney cell and A549 human lung cancer cells using PAM-ABP. The pSV-Luc was transfected as a control. The complexes were prepared at a 5:1 (carrier: pDNA) weight according to the previous study [14]. Forty-eight hours after the transfection, the cell lysates were harvested and luciferase assay was performed. In hepatoma cells, pAFPL-Luc showed up to 200 folds higher luciferase activity (RLU/mg total protein) than pAFPS-Luc. Although the pAFPS-Luc had higher gene expression level than pSV-Luc, the induction fold was only up to 50 fold (Fig. 3A and 3B). In contrast, non-hepatoma cell lines (normal kidney or lung cancer cells) did not show this effect. There was no significant difference among the three plasmids in 293 and A549 cells (Fig. 3C and 3D). From the results, we confirmed the promoter activity of pAFPS-Luc or pAFPL-Luc increased gene expression specifically in the hepatoma cells. The AFPL promoter was chosen for further modification for hypoxia specificity, due to its higher hepatoma targeting promoter activity in this study.

Figure 3. Hepatoma cell specific gene expression efficiency.

pSV-Luc, pAFPS-Luc and pAFPL-Luc were trasnfected into (A) Huh7 (B) HepG2 (C) 293 and (D) A549 cell lines. The cells were incubated for 48hrs and assessed for luciferase activity. The data expressed as mean values (±standard deviation) of triplicate experiments. *P<0.05 as compared with pAFPS-Luc.

3.4. Transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity of PAM-ABP

Transfection condition of PAM-ABP was optimized using pAFPL-Luc plasmid. The complex was prepared at various weight ratios and transfected into Huh7 hepatoma cells. In the result, the highest transfection efficiency of PAM-ABP was observed at a 5:1 (PAM-ABP/pDNA) weight ratio. Therefore, complex weight ratio was fixed at a 5:1 in further studies (Fig. 4A). To confirm the cytotoxicity of PAM-ABP in hepatoma cells, viability of transfected cells was measured by MTT assay (Fig. 4B). The complex of PAM-ABP/pDNA was prepared by increase of PAMABP weights with constant amount of pDNA. PEI25K and lipofectamine were used as controls. In the results, the PAM-ABP/pDNA complexes at various ratios including optimum transfection ratio showed higher cell viability than the PEI25K/pDNA and lipofectamine/pDNA complexes. The transfection efficiency of PAM-AMP was compared with PEI25K and lipofectamine (Fig. 4C). As a result, PAM-ABP showed higher transfection efficiency than PEI25K and lipofectamine in hepatoma cells. Transfection efficiency was also compared in non-hepatoma cells, A549 and 293 cells. Although the PAM-ABP showed slightly lower transfection efficiency than PEI25K and lipofectamine in A549 cells, it showed high transfection efficiency rate, comparable to PEI25K and lipofectamine in various cells. In addition, the result also elucidated that the hepatoma specific gene expression efficiency of pAFPL-Luc. The hepatoma cells showed ~200 times higher luciferase activity than non-hepatoma cells.

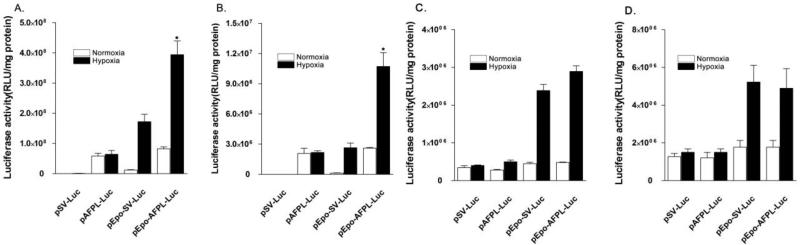

3.5. Construction of hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression vector and in vitro transfection assay

Most solid tumors include hepatoma have hypoxic regions. Therefore, tumor hypoxa is an outstanding target for tumor targeting. To increase gene expression under hypoxic hepatoma cell, pEpo-AFPL-Luc was constructed by insertion of the Epo enhancer at the upstream of the AFPL promoter of pAFPL-Luc (Fig. 5). It was previously reported that the Epo enhancer contain hypoxia response element (HRE) and it could induce the hypoxia inducible gene expression [15]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the combination of the Epo enhancer with the AFPL promoter may have dual specificity to hypoxic hepatoma. To evaluate the hypoxia specificity of pEpo-AFPL-Luc, PAM-ABP/ pEpo-AFPL-Luc complex was transfected into Huh7 and HepG2 cells. pSV-Luc, pAFPL-Luc and pEpo-SV-Luc were used as control pDNAs. After transfection, the cells were incubated under normoxia or hypoxia for 48 hrs. The pEpo-AFPL-Luc transfected group demonstrated that significantly higher luciferase activity (~ 4 times higher induction folds) in both cells under hypoxic condition, compared with normoxic condition (Fig. 6A and B). Although the Epo-SV-Luc also showed increasing of gene expression under hypoxia, the levels were lower than pEpo-AFPL-Luc. The pAFPL-Luc did not show hypoxia inducible gene expression. PAM-ABP/pDNAs complexes were also transfected into non-hepatoma cells, 293 and A549. In the results, pEpo-SV-Luc and pEpo-AFPL-Luc showed increasing luciferase activity under hypoxic condition because of the Epo enhancer. However, there is no significant difference between pSV-Luc and pAFPL-Luc transfected group under normoxia or hypoxia condition (Fig. 6C and D).

Figure 5. Structure of hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression plsmid.

The diagram shows the structure of the luciferase reporter gene constructs containing the Epo enhancer and AFPL promoter. E indicates the Epo enhancer.

Figure 6. Gene expression levels by pEpo-AFPL-Luc under normoxia or hypoxia.

pSV-Luc, pAFPL-Luc, pEpo-SV-Luc and pEpo-AFPL-Luc were trasnfected into (A) Huh7 or (B) HepG2 (C)293 (D) A549 cells. PAMABP was used as a carrier.The cells were incubated for 48 hrs under normoxia or hypoxia condition and assessed for luciferase activity. The data expressed as mean values (±standard deviation) of quadruplicate experiments. *P<0.05as compared with Epo-SV-Luc under hypoxia and pEpo-AFPL-Luc under normoxia.

3.6. Therapeutic effect of hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific TK gene expression vector

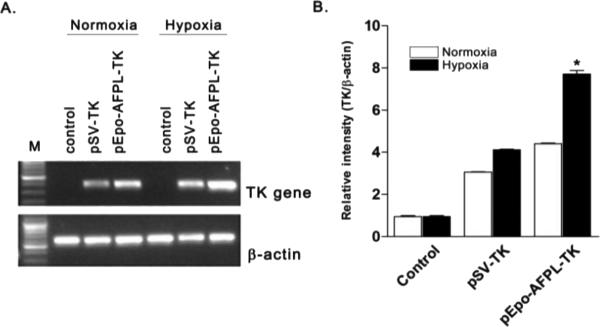

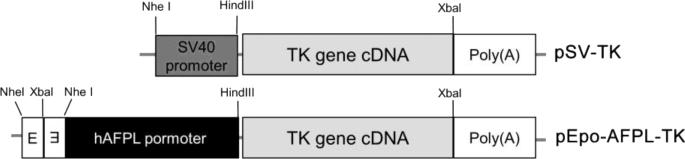

The TK gene was employed to confirm the therapeutic effect of dual specific gene expression vector. A TK therapeutic gene expression pDNA, pEpo-AFPL-TK was constructed. The structure of constructed vectors was presented in the figure 7. To verify the dual specific TK gene expression, mRNA level was measured by RT-PCR. pSV-TK was used as a control. The TK gene transfected group showed the amplified band of the TK mRNAs, whereas nontransfected cell did not shown that (Fig. 8A). Among the TK expressing groups, the highest TK mRNA level was observed in pEpo-AFPL-TK transfected hypoxic hepatoma cells (~7.7 times higher intensity than the control). The result demonstrated that the TK gene expression of pEpo-AFPL-TK was activated by transcriptional regulatory elements in the Epo enhancer and AFP promoter. The Epo-enhancer and the AFP promoter showed much higher TK gene expression under hypoxia than normoxia (Fig. 8B).

Figure7. The TK therapeutic gene expression plasmid constructs.

pEpo-AFPL-TK was constructed by replacement of luciferase gene in the pSV-Luc and pEpo-AFPL-Luc with TK gene.

Figure 8. The expression level of TK mRNA.

(A) Gel electrophoresis and (B) Gel intensity quantification. pSV-TK and pEpo-AFPL-TK were transfected into Huh7 cells using PAM-ABP and incubated for 48hrs under normoxia or hypoxia. Control indicates non-transfected Huh7 cells. The mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR and the results were quantified using an image J gel analyzer progrom (NIH image). *P<0.05 compared with pEpo-AFPL-TK under normoxia.

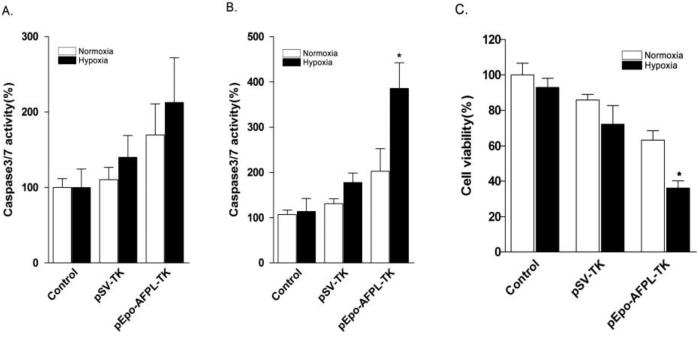

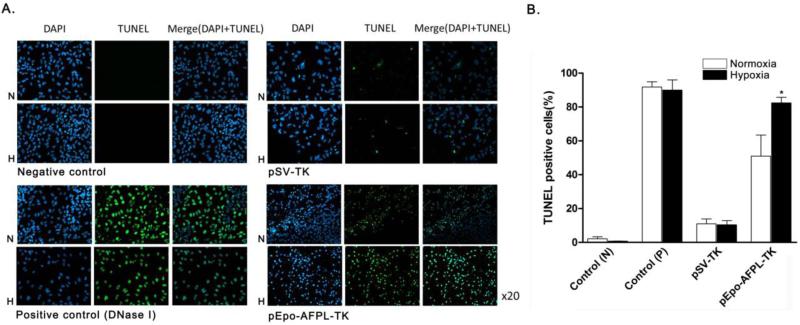

Incorporation of triphosphated GCV into the replicated DNA inhibits the synthesis of DNA and induces apoptosis. Therefore, after the transfection of PAM-ABP/SV-TK or pEpo-AFPL-TK complexes in the presence of GCV, the apoptosis of hepatoma was measured by caspase-3/7 activity assay and TUNEL assay. The caspase-3/7, apoptosis mediated enzyme, activity was measured in TK gene transfected Huh7 cells (Fig. 9A and 9B). The cells were incubated with GCV (100 μg/ml) under hypoxia or normoxia for 24 or 48 hrs. The results showed that pEpo-AFPL-TK more efficiently induced cell apoptosis in hypoxic hepatoma cells than normoxic cells. Even though there was no statistical significance, the caspase-3/7 activity was slightly increased in TK transfected cells after 24hrs incubation (Fig. 9A). After the 48 hrs incubation, the enzyme activity significantly increased in Epo-AFPL-TK transfected cells under hypoxia compared to control and pSV-Luc (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, the cell death rate was measured by MTT assay and the result observed similar tendency in the figure 9C. The pEpo-AFPL-TK showed highest cell death rate (~65%) under hypoxic condition. It also increased cell death rate in normoxia (~35%) condition compared to control and pSV-TK, resulting in tissue specificity of AFPL promoter. Finally, the apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay (Fig. 10). pSV-TK or pEpo-AFPL-TK was transfected into Huh7 cells and then incubated for 48 hrs with GCV. The DNase I (10 units) treatment group was supplement to positive control. Because of hepatoma specific promoter activity, high level of apoptotic cells were observed in pEpo-AFPL-TK transfected hepatoma cells under normoxia condition. In hypoxia condition, the pEpo-AFPL-TK had the larger amount of apoptotic cells than pEpo-AFPL-TK under normoxia and pSV-TK (Fig. 10A). For quantitative analysis, the TUNEL positive cells were counted in five random area images for each sample (~700 cells were counted for group). TUNEL positive cells were represented with the percentile by TUNEL positive over DAPI positive (Fig. 10B). More than 90 % of apoptosis positive cells were detected in DNase treatment control whereas only a few positive cells (~2%) were detected in negative control and SV-TK had ~10% apoptotic cells under normoxia or hypoxia. However, the pEpo-AFPL-TK transfected hepatoma cells showed ~50% and ~80% apoptotic cells under normoxia and hypoxia, respectively. Taken together, these data suggest that the TK gene expression tightly regulated by the Epo enhancer and the AFP promoter for specific increase of gene expression and apoptosis in hypoxic hepatoma cells.

Figure 9. Apoptosis induced cell death by pEpo-AFPL-TK.

Caspase-3/7 activity was measured for (A) 24 hrs and (B) 48 hrs incubation under normoxia or hypoxia with GCV. The PAM-ABP/pSV-TK or pEpo-AFPL-TK complex was transfected into Huh7 cells. Caspase-3/7 activity assessed for RLU activity. (C) Cell death rates were measured by MTT assay. The data expressed as mean values (±standard deviation) of quadruplicate experiments. *P<0.05 as compared with pEpo-AFPL-TK under normoxia and pSV-TK under hypoxia.

Figure 10. TUNEL assay.

TUNEL assay was presented by (A) fluorescence microscopy images and (B) TUNEL positive cell counting (%). PAM-ABP/pSV-TK or pEpo-AFPL-TK complex was transfected into Huh7 cells with GCV (100μg/ml). After 48 hrs incubation, TUNEL assay was performed. The data are expressed as mean values (±standard deviation) of triplicate experiments. *P<0.05 as compared with pEpo-AFPL-TK under normoxia.

4. Discussion

Therapeutic gene expression vectors should be tightly regulated for safe and successful gene therapy. For this purpose, we constructed the hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression vector. Up to now, many promoters have been developed for hepatoma specific gene expression. Among them, the AFP promoter is most widely used promote [18-20]. Transcription factors including hepatocyte nuclear factors 1(HNF1), C/EBP, HNF3 and HNF4 attribute to high level of AFP gene expression. The human AFP gene enhancer has important regulatory region in −4.0/−3.7 and −3.7/−3.3kbp. Although hepatoma tissue specific AFP gene expression is controlled by its promoter and enhancer, the promoter activity is relatively weak compared with enhancer, which is incomplete for gene therapy [21]. In this study, for tighter and stronger regulation of gene expression, hepatoma tissue and cancer hypoxia dual targeting vectors were constructed. In order to determine the hepatoma specificity, we used two types of AFP promoters i) the AFPS promoter: only AFP promoter region or ii) the AFPL promoter: AFP promoter with enhancer regulatory region (~0.4kbp). The higher hepatoma specificity was observed in AFPL promoter because of the existence of regulator region (Fig. 1, 3 and 4). Therefore, AFPL was used for combination with the Epo enhancer.

A hypoxic region is one of the characteristics of the solid tumors. It is caused by high proliferation of tumor cells and the inadequate vasculature development [22]. For a long time, many studies have been developed hypoxia targeting gene expression vectors and applied to ischemic disease and cancer [23, 24]. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1 (HIF-1) is a main transcription factor that plays a major role in hypoxic expression of a variety of genes. Most of hypoxia targeting vectors has been developed using transcriptional regulatory systems with hypoxia inducible promoters [25]. To achieve high specificity to hypoxic tumor cells, many hypoxia-response therapeutic gene expression vectors have been constructed. For example, the VEGF promoter–driven diphtheria toxin was fused to a part of HIF-1 ODD domain. In the results, the hypoxia- regulated toxin expression that induced apoptosis of hypoxic tumors and minimized gene expression in normal tissues [26]. In addition to the promoters, some HRE baring enhancers were used for hypoxia specific gene expression. For instance, the Epo 3’ enhancer with SV40 promoter system was reported to hypoxia inducible gene expressions [15]. Unlike the promoter systems, the enhancers can induce gene expression regardless of their location and orientation. Therefore, the combination of the enhancers with the promoters is relatively easy to construct. Furthermore, the enhancers are combined with the promoters for dual specificity easily, thanks to the less sensitivity of the enhancers to orientation and position. In this study, the Epo enhancer was used for hypoxia specific gene expression. The pEpo-AFPLLuc or pEpo-AFPL-TK transfected hepatoma cells clearly increased luciferase activity or TK gene expression levels under hypoxic condition (Fig. 6 and 8). These results demonstrated that pEpo-AFPL-Luc had the synergistic effect by the Epo enhancer and the AFP promoter combination strategy.

The TK/GCV systems have been used in several clinical trials and some promising results were achieved in various different types of cancers [27, 28]. For example, TK gene was delivered by cationic liposomal vector for glioblastoma treatment and some patients showed positive results [29]. Sangro et al. demonstrated that the TK gene had therapeutic effects in some patients who received non-toxic administration dose adenoviral vector encoding TK gene at the phase I clinical trial [30]. However, many suicide genes therapy in these studies have a single regulatory gene expression system. Since hypoxic regions of cancer is very difficult to deliver and express a sufficient therapeutic gene without side-effects to normal tissue, hypoxia targeted high delivery efficiency and specificity are necessary for efficient gene therapy [31]. In this study, to confirm the therapeutic effect of a dual targeting vector, the TK gene was used as a therapeutic gene. The efficacy of pEpo-AFPL-TK was elucidated by tumor cell death rates. Since the promoter activity, normoxic hepatoma cell death also observed in pEpo-AFPL-TK. The hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific pEpo-AFPL-TK vector additionally increased the TK gene expression level in hypoxic hepatoma resulting in higher hepatoma cell death rates than non-targeting SV-TK vector under (Fig. 9 and 10). The dual specific gene expression vector affected not only hepatoma cells but hypoxic cells. Therefore, therapeutic efficacy was increased by synergistic effect of dual specific vector. These results implicated that the novel dual specific therapeutic gene expression vector might be benefit to apply the system in other cancer cells with high efficiency and safety.

Because of the low gene delivery efficiency of non-viral carrier, improve the efficiency and reduce the cytotoxicity are one of the key goals to make effective gene delivery system. Based on these considerations, several types of bio-reducible polymers were developed [32, 33]. For example, reducible poly (oligo-D-arginine), rPOA, was developed as an efficient DNA delivery carrier with low toxicity [34]. Previously, ABP was synthesized and evaluated as a gene delivery carrier. Although ABP showed highly effective in vitro, it had limitation for application due to the optimizing delivery condition required too high amount of ABP in vivo [13]. Therefore, dendrimer type bio-reducible polymer, PAM-ABP, was developed to improve the weakness of ABP. The increased molecular weight of the PAMAM conjugated ABP showed lower weight ratio than ABP to optimize the transfection condition. The PAM-ABP showed well condensed nanoparticle with pDNA and efficiently delivered gene into the many types of cells with low toxicity [14]. In this study, we showed that PAM-ABP could effectively deliver the genes in to the hepatoma cell. Moreover, low cytotoxicity of PAM-ABP was confirmed in hepatoma cells (Fig. 3). PAM-ABP/pEpo-AFPL-TK system had a low cytotoxicity and the delivered genes only expressed in hypoxic hepatoma cells. Therefore, the hepatoma gene therapy with PAM-ABP/pEpo-AFPL-TK system may be as the strong strategy the hepatoma gene therapy

4. Conclusion

In this study, we constructed the hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression vector for hepatoma specific gene therapy. The system was composed of two regulatory elements. One was the Epo enhancer for hypoxia specific gene regulation and the other was the AFP promoter for hepatoma specific gene expression. The dual specific plasmid was delivered to hypatoma cells using bio-reducible polymer, PAM-ABP. PAM-ABP efficiently delivered pDNA into hepatoma cells with low cytotoxicity. In vitro transfection assay demonstrated that combination of the Epo enhancer and the AFP promoter specifically increased gene expression under hypoxic hepatoma cells. Moreover, pEpo-AFPL-TK could maximize the hepatoma cell apoptosis under hypoxic condition. The results suggest that hypoxia/hepatoma dual specific gene expression plasmid with a bio-reducible polymer might be useful for safe and efficient hepatoma gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants CA107070 (S.W.Kim) and a grants from the National Research Foundation in Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 2012K001394 (M.Lee), Basic Science Research Program 2012R1A6A3A03040715(H.A.Kim)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.El–Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuster J, García-Valdecasas JC, Grande L, Tabet J, Bruix J, Anglada T, Taurá P, Lacy AM, González X, Vilana R. Hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis. Results of surgical treatment in a European series. Annals of surgery. 1996;223:297. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum HE. Hepatocellular carcinoma: therapy and prevention. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;11:7391. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Lu X-X, Chen D-Z, Li S-F, Zhang L-S. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase and ganciclovir suicide gene therapy for human pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;10:400–403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rich JN, Reardon DA, Peery T, Dowell JM, Quinn JA, Penne KL, Wikstrand CJ, Van Duyn LB, Dancey JE, McLendon RE. Phase II trial of gefitinib in recurrent glioblastoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:133–142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee RJ, Springer ML, Blanco-Bose WE, Shaw R, Ursell PC, Blau HM. VEGF gene delivery to myocardium: deleterious effects of unregulated expression. Circulation. 2000;102:898–901. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ido A, Uto H, Moriuchi A, Nagata K, Onaga Y, Onaga M, Hori T, Hirono S, Hayashi K, Tamaoki T. Gene Therapy Targeting for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Selective and Enhanced Suicide Gene Expression Regulated by a Hypoxia-inducible Enhancer Linked to a Human α-Fetoprotein Promoter. Cancer research. 2001;61:3016–3021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saukkonen K, Hemminki A. Tissue-specific promoters for cancer gene therapy. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2004;4:683–696. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamaoki T, Fausto N. Expression of the a-fetoprotein gene during development, regeneration, and carcinogenesis. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JM. The Hypoxic Cell A Target for Selective Cancer Therapy—Eighteenth Bruce F. Cain Memorial Award Lecture. Cancer research. 1999;59:5863–5870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelstein ML, Abedi MR, Wixon J, Edelstein RM. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide 1989–2004—an overview. The journal of gene medicine. 2004;6:597–602. doi: 10.1002/jgm.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T.-i., Ou M, Lee M, Kim SW. Arginine-grafted bioreducible poly (disulfide amine) for gene delivery systems. Biomaterials. 2009;30:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nam HY, Nam K, Lee M, Kim SW, Bull DA. Dendrimer type bio-reducible polymer for efficient gene delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee M, Rentz J, Bikram M, Han S, Bull D, Kim S. Hypoxia-inducible VEGF gene delivery to ischemic myocardium using water-soluble lipopolymer. Gene therapy. 2003;10:1535–1542. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HA, Park JH, Cho SH, Lee J, Lee M. Glia/ischemia tissue dual specific gene expression vector for glioblastoma gene therapy. Journal of Controlled Release. 2011;152:e146–e148. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HA, Park JH, Lee S, Choi JS, Rhim T, Lee M. Combined delivery of dexamethasone and plasmid DNA in an animal model of LPS-induced acute lung injury. Journal of Controlled Release. 2011;156:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa H, Nakata K, Mawatari F, Ueki T, Tsuruta S, Ido A, Nakao K, Kato Y, Ishii N, Eguchi K. Utilization of variant-type of human α-fetoprotein promoter in gene therapy targeting for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene therapy. 1999;6:465–470. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyatake S, Tani S, Feigenbaum F, Sundaresan P, Toda H, Narumi O, Kikuchi H, Hashimoto N, Hangai M, Martuza R. Hepatoma-specific antitumor activity of an albumin enhancer/promoter regulated herpes simplex virus in vivo. Gene therapy. 1999;6:564. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh Y-J, Chen F-D, Ke C-C, Wang H-E, Huang C-J, Hou M-F, Lin K-P, Gelovani JG, Liu R-S. The EIIAPA chimeric promoter for tumor specific gene therapy of hepatoma. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2012;14:452–461. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0509-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakabayashi H, Hashimoto T, Miyao Y, Tjong K, Chan J, Tamaoki T. A position-dependent silencer plays a major role in repressing alpha-fetoprotein expression in human hepatoma. Molecular and cellular biology. 1991;11:5885–5893. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.5885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11:393–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binley K, Iqball S, Kingsman A, Kingsman S, Naylor S. An adenoviral vector regulated by hypoxia for the treatment of ischaemic disease and cancer. Gene therapy. 1999;6:1721. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M, Lee ES, Kim YS, Choi BH, Park SR, Park HS, Park HC, Kim SW, Ha Y. Ischemic injury-specific gene expression in the rat spinal cord injury model using hypoxiainducible system. Spine. 2005;30:2729–2734. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000190395.43772.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HA, Mahato RI, Lee M. Hypoxia-specific gene expression for ischemic disease gene therapy. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2009;61:614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koshikawa N, Takenaga K. Hypoxia-regulated expression of attenuated diphtheria toxin a fused with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain preferentially induces apoptosis of hypoxic cells in solid tumor. Cancer research. 2005;65:11622–11630. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu F, Li S, Li X, Guo Y, Zou B, Xu R, Liao H, Zhao H, Zhang Y, Guan Z. Phase I and biodistribution study of recombinant adenovirus vector-mediated herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene and ganciclovir administration in patients with head and neck cancer and other malignant tumors. Cancer gene therapy. 2009;16:723–730. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klatzmann D, Valery CA, Bensimon G, Marro B, Boyer O, Mokhtari K, Diquet B, Salzmann J-L, Philippon J. A phase I/II study of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase “suicide” gene therapy for recurrent glioblastoma. Human gene therapy. 1998;9:2595–2604. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.17-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voges J, Reszka R, Gossmann A, Dittmar C, Richter R, Garlip G, Kracht L, Coenen HH, Sturm V, Wienhard K. Imaging-guided convection-enhanced delivery and gene therapy of glioblastoma. Annals of neurology. 2003;54:479–487. doi: 10.1002/ana.10688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sangro B, Mazzolini G, Ruiz M, Ruiz J, Quiroga J, Herrero I, Qian C, Benito A, Larrache J, Olagüe C. A phase I clinical trial of thymidine kinase-based gene therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer gene therapy. 2010;17:837–843. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kizaka-Kondoh S, Inoue M, Harada H, Hiraoka M. Tumor hypoxia: a target for selective cancer therapy. Cancer science. 2005;94:1021–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luten J, van Nostrum CF, De Smedt SC, Hennink WE. Biodegradable polymers as non-viral carriers for plasmid DNA delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2008;126:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim T.-i., Kim SW. Bioreducible polymers for gene delivery. Reactive and Functional Polymers. 2011;71:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Won Y-W, Kim HA, Lee M, Kim Y-H. Reducible poly (oligo-D-arginine) for enhanced gene expression in mouse lung by intratracheal injection. Molecular Therapy. 2009;18:734–742. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]