Abstract

One of the worst HIV/AIDS epidemics in the world is occurring in South Africa, where heterosexual exposure is the main mode of HIV transmission. Young people 15–24 years of age, particularly women, account for a large share of new infections. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for behavior-change interventions to reduce the incidence of HIV among adolescents in South Africa. However, there are few such interventions with proven efficacy for South African adolescents, especially young adolescents. A recent cluster-randomized controlled trial of the ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for Grade 6 South African adolescents (mean age = 12.4 years) found significant decreases in self-reported sexual risk behaviors compared with a control intervention. This article describes the intervention, the use of the social cognitive theory and the reasoned action approach to develop the intervention, how formative research informed its development and the acceptability of the intervention. Challenges in designing and implementing HIV/STD risk-reduction interventions for young adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa are discussed.

Introduction

More than two-thirds of the 34.0 million people living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2011 resided in sub-Saharan Africa, where heterosexual exposure is the main mode of HIV transmission [1]. South Africa has the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the world [1]. About 18.1% of South Africans aged 15–49 years are infected with HIV, and people aged 15–24 years, particularly women, account for a large share of new infections [2]. Although antiretroviral therapy is increasingly available in South Africa, behavior change remains critical to stemming the epidemic [3–5], and culturally congruent interventions to promote abstinence, condom use and limited sexual partnerships among young adolescents who have not established habitual patterns of sexual behavior are especially needed.

However, reviews of the literature reveal few efficacious behavior-change interventions specific to South African adolescents or adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa more generally [6–9]. Most studies were conducted with older adolescents, with a mean age of 13.5 years or older. Harrison et al. [8] identified eight intervention studies in South Africa that were school- or group-based, involving in- and out-of-school youth, and delivered by teachers, peer educators and older mentors. Five were developed outside of South Africa and adapted using qualitative research with the target population; one adapted specific modules from several effective interventions from the United States and South Africa.

A recent school-based randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention was conducted with 1057 sixth grade learners from 18 randomly selected schools in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa [10]. The learners ranged in age from 9 to 18 years (mean = 12.4); only 3.3% reported ever having intercourse. The results revealed that learners in the schools that received the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention had a lower odds of reporting intercourse, unprotected intercourse and multiple partnerships during a 12-month follow-up period than did those in a health-promotion intervention [11], a control condition not covering sexual risks but matching the time and attention the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention participants received [12,13]. ‘Let Us Protect Our Future’ also caused positive changes on hypothesized mediators of intervention efficacy [14]. This article describes the intervention, its theoretical framework, the formative research that informed its development and the acceptability of the intervention.

Methods

Theoretical framework

The ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ intervention was developed based on the social cognitive theory [15,16], the theory of reasoned action [17,18] and its extension the theory of planned behavior [19] integrated with qualitative information about the target population from formative research. Several aspects of social cognitive theory are relevant to behavior-change intervention. Outcome expectancies are the consequences people expect if they perform a particular behavior. Self-efficacy is the confidence people have that they can perform a behavior despite challenges and setbacks. The theory also holds that behavior change may require skills, which in the case of sexual behaviors, include interpersonal skills, technical skills to use condoms and self-regulatory skills in guiding and motivating action [20]. However, those with strong self-efficacy beliefs will exert more effort and persistence and thus are more likely to succeed than their low-efficacy counterparts who have the same skills.

The theory of reasoned action [17,18] and the theory of planned behavior [19] collectively are called the ‘reasoned action approach’ [21], which holds that intention is the main determinant of behavior, and attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control or self-efficacy regarding the behavior determine intention. It further holds that behavioral beliefs about the consequences of the behavior, a construct similar to outcome expectancies, determine attitude, normative beliefs about important referents’ approval or disapproval of the behavior determine subjective norm, and control beliefs about factors that facilitate or inhibit performing the behavior determine self-efficacy. We felt that the theory’s focus on norms of peers and partners was particularly appropriate for young adolescents, who are engaged in the process of identity formation through social comparison [22].

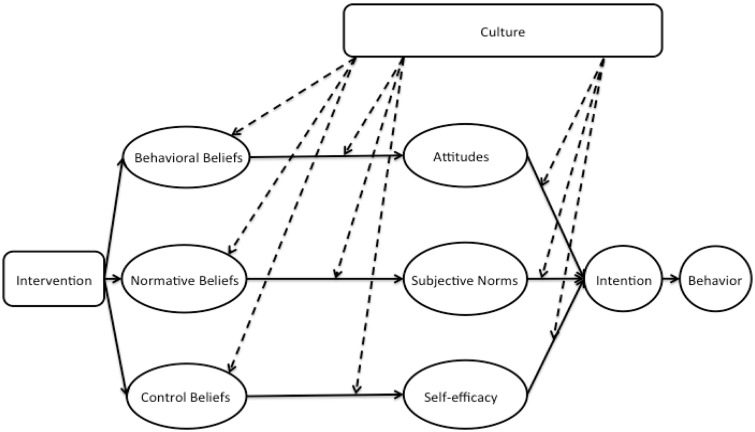

It might be argued that the reasoned action approach has limitations for use in South African cultures, where family and the broader community have large influences on behavior. However, in accord with the reasoned action approach, behavioral beliefs and control beliefs about condom use have been tied to the intention to use condoms among young South African adolescents [23]. Moreover, certain features of the approach make it excellent for use in South Africa [24]. For instance, the approach allows the possibility that the relative importance of attitudinal, normative and self-efficacy determinants of intention and behavior may vary in different cultures. Attitudinal determinants might be especially important in one culture, whereas normative determinants (e.g. normative beliefs about family and community) might be especially important in another culture. More generally, the approach can accommodate culture in several ways: as shown in Fig. 1, culture can affect the beliefs people hold, the relations of beliefs to the determinants of intention—attitude, subjective norm and self-efficacy—and the relation of those determinants to intention. Another feature of the reasoned action approach that lends cross-cultural utility is the strategy it offers for identifying the relevant behavioral, normative and control beliefs: conducting formative research with the population to identify population-relevant beliefs about the behavior, which may be different for different populations. Identifying and targeting those beliefs tailor a reasoned action intervention to the specific population.

Fig. 1.

A model of the integration of culture into the reasoned action approach. Culture can influence beliefs, the relations of beliefs to attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy, and the relations of attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy to intention.

Formative research

To support the development of the intervention and a questionnaire to evaluate its efficacy, we conducted focus groups at schools. Male and female isiXhosa- and English-speaking facilitators age 30 years and older who had at least a college degree led all focus groups following standard protocols and scripts. Questions were included to elicit behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs [21] that were common in the population and therefore potential targets of the intervention. Additional questions concerned cultural factors and contexts relevant to HIV sexual-risk behaviors. Qualitative analysis on data from facilitators’ and researchers’ notes and transcripts of audiotaped sessions identified and categorized themes or patterns of responses relevant to intervention development.

Participants

The formative research participants were 89 isiXhosa-speaking sixth grade learners who participated in nine focus groups, 34 parents of sixth grade learners who participated in four groups and 12 teachers of sixth grade learners who participated in one group. These groups were held between January 2001 and February 2003. Between October 2003 and May 2004, sixth grade learners participated in three pilot tests of the interventions: 30 in the first pilot, 43 in the second and 43 in the third. All learners and teachers were recruited through announcements at their schools, and parents were recruited through letters their children received in school and took home.

Besides conducting formative research, we established a community advisory board of parents, teachers, school principals, physicians and representatives from the Ministries of Health and Education and non-governmental organizations that served adolescents. They advised us on the design and implementation of the intervention study and the cultural, gender, contextual appropriateness and feasibility and acceptability of the interventions. For instance, they suggested that rather than our original choice as male facilitators, ikhankatha—the men who played the educational role in the circumcision rites of passage for young men—that we train unemployed teachers and other respected men from the community irrespective of whether they were ikhankatha. They suggested that we address sexual and reproductive health in single-gender groups. In addition, they suggested that we include schools in a nearby semi-rural settlement, Berlin, rather than only schools in the urban township, Mdantsane.

Description of the intervention

‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ was designed to: (i) increase HIV/STD risk-reduction knowledge and decrease cultural myths about HIV, (ii) enhance behavioral, normative and control beliefs supporting abstinence, condom use and limiting the number of sexual partners and (iii) increase skill and self-efficacy to negotiate and practice abstinence and condom use. It consists of 12 1-h modules of interactive activities, games, brainstorming, role-playing, comic workbooks and small-group discussions.

A structural reality that influenced the intervention’s design was lack of electricity in many schools, which meant we could not employ videos, a valuable component of many efficacious interventions [25–29]. We surmounted this challenge by creating comic workbooks with a series of characters and storylines addressing HIV/AIDS, stigma, pregnancy, the impact of risky behaviors on goals and dreams, abstinence, condom use and coercive sex. According to social cognitive theory, skills practice with performance feedback is an effective way to increase self-efficacy and behavioral skills [15,30]. However, a challenge to skills building with young adolescents is that they may be reluctant to participate in role-plays. To help address this challenge, instead of facilitators reading aloud the characters’ dialogs, participants read them aloud, which helped prepare them for the graduated series of scripted, partially scripted and unscripted role-plays in the final session.

Adolescent focus group participants suggested the name of the intervention, which became its theme. Initially, we thought the name would be ‘Protect Our Future!’. However, the participants made clear that they meant, ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’. We infused this theme, which reflects a more collectivist perspective rather than an individualistic perspective, throughout the intervention. As shown in Fig. 2, the logo is an image of the traditional shield that protects adolescents and their family and includes the main characters in the comic workbooks—the mother, father, sister, brother, older sister and teacher—with the shield behind them. The names of the brother ‘Khusela’, meaning ‘protect’ in isiXhosa, and his twin sister, ‘Nangamso’, meaning ‘future’, also suggested by the adolescent focus groups, dovetail nicely with the intervention’s theme.

Fig. 2.

‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ logo.

The comic workbooks also provided a way to incorporate testimonials and narrative, which according to social cognitive theory [15] are ways to address outcome expectancies and self-efficacy. The comic workbook characters, Khusela and Nangamso, faced challenges similar to those of the adolescents, which provided the opportunity for participants to read about and discuss how the characters grappled with realistic challenges. For example, in addressing inappropriate romantic relationships, cross-generational sex, and exchanging sex for gifts, issues that came up in the focus groups, the supporting comic storyline featured Khusela writing a love poem for a girl he likes. His twin sister, Nangamso, is anxious to learn for whom he wrote the poem. In the next episode, however, participants learn that Khusela’s love interest was, in fact, his math teacher.

As we shall see shortly, the focus groups revealed that parents had difficulty talking to their children about sex. Accordingly, we employed take-home assignments to increase parent–child communication, to enlist parents’ help in empowering their children and to ensure that parents were aware of the nature of the interventions. As shown in Table I, the topics addressed were initially benign, but became increasingly sensitive over the series of assignments. At the succeeding session, participants shared any difficulties they encountered in talking with their parent and brainstormed possible strategies to overcome those difficulties.

Table I.

Take-home assignments in the Let Us Protect Our Future intervention by intervention session

| Session | Take-home assignment |

|---|---|

| 1 | Discuss concerns the parent had about the child’s growing up, things parents wished they discussed more with the child, parent’s goals and dreams for the child, the child’s own goals and dreams, obstacles to the child’s goals and dreams and ways to overcome those obstacles. |

| 2 | Discuss HIV/AIDS, ways people get HIV, the meaning of abstinence, why abstinence is important, how HIV can interfere with the child’s goals and dreams and how abstinence can help the child achieve his or her goals and dreams. |

| 3 | Discuss facts the child learned about HIV in the session |

| 4 | Discuss the parent’s advice on how the child might handle a series of scenarios (e.g. someone wants to kiss them, a boyfriend/girlfriend wants to touch them below the waist, someone wants to have sex with them). |

| 5 | The children were to pretend they were the host of a radio talk show presented with HIV sexual-behavior risk problems from callers. They were to discuss the callers’ problems with their parent and write down advice to the caller. In addition, the child and parent signed a pledge to always talk in the future. |

Note: Each intervention session included 2 of the 12 modules of the intervention. Session 6 did not have a take-home assignment because it was the final intervention session.

Traditionally, in amaXhosa culture, women should not discuss sexual and reproductive health matters with boys, and men should not discuss such matters with girls. To ensure that participants felt comfortable, the comic workbook was used to introduce puberty and adolescent sexuality in single-sex groups led by the same-sex facilitator. Thus, girls could have fruitful conversations about topics such as Nangamso’s first period with their peers and female facilitator, whereas boys discussed Khusela’s wet dream with their male peers and facilitator.

Besides the intervention’s theme, the series of comic workbooks, the graduated series of take-home assignments and the single-gender activities already mentioned, we created additional activities. For instance, hats have special significance in amaXhosa culture, which led us to create a ‘Hat Activity’ to help participants consider the many roles or ‘hats’ they wear in life and to address self-pride. We created a ‘Doll Activity’ to address attitudes toward women and sexual coercion. Participants used dolls with changeable clothing to express their views on how young women dress and considered whether a girl who dresses sexy is asking for sex or deserves to be forced to have sex. To build the participants’ self-efficacy and skill to avoid risky situations, we created the ‘Long Walk Home’ in which participants identified risky situations they may encounter en route to and from school, traced the safest path to avoid dangerous situations and brainstormed strategies to reduce their risk of sexual coercion.

To address some issues, we adapted existing activities from other efficacious interventions that seemed appropriate [31–33]. For instance, we adapted an activity on goals and dreams for the future [31–33] in which the adolescents considered how abstaining from sex or using condoms could help achieve their goals and dreams. In another activity, the ‘Benefits of Abstinence’, [31] participants brainstormed the good and bad things about abstinence even if they were sexually experienced and considered what it takes to practice abstinence successfully. To build condom-use self-efficacy and skill, in a ‘Correct Condom Use’ activity, participants learned the steps of using condoms correctly and practiced by putting condoms on anatomical models after the facilitators modeled the skill [32,33].

We implemented the intervention in isiXhosa following translation and back-translation to English. In the target communities, people did not generally refer to genital organs or sexual activity with isiXhosa words. Indeed, such words were considered obscene (Z. Ngwane et al., submitted for publication). People were more comfortable with English or other foreign equivalents. To balance respect for the culture with using language that the adolescents would understand, we ‘Xhosalized’ certain words, creating a hybrid of English and isiXhosa to maximize both comfort and understanding. For example, in discussing body parts, we mixed English and isiXhosa terms by adding the isiXhosa article ‘i’ at the beginning of words such as ‘ivagina’ for vagina and ‘ipenis’ for penis.

In the main trial, we implemented ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ and the health-promotion attention-control intervention during the extracurricular activity period at the end of the school day with learners who provided parent/guardian informed consent and adolescent assent to participate rather than attend other extracurricular activities. We implemented the 12 modules of the intervention in six 2-module sessions on consecutive school days. To accommodate the academic calendars of the schools and our personnel resources, we divided the nine matched-pairs of schools into three groups in implementing the trial. Pairs 1–3 received the interventions in October and November 2004; pairs 4–6 received the interventions in January, February and March 2005 and pairs 7–9 in October and November 2005, with 12-month follow-up data collection completed in December 2006 [10]. Table II lists the activities and the variables addressed in the modules.

Table II.

‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ curriculum modules, activities and variables targeted

| Module | Module title | Activities | Variables targeteda |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Getting to know you |

|

|

| 2. Single gender | Puberty and adolescent sexuality (male version and female version) |

|

|

| 3. Single gender | What it means to be a young man/woman (male version and female version) |

|

|

| 4. | Romantic relationships and being in love |

|

|

| 5. | Consequence of sex: HIV infection |

|

|

| 6. | Consequences of sex: STDs and unplanned pregnancy |

|

|

| 7. | Responding to risk situation |

|

|

| 8. | Taking care of your future |

|

|

| 9. | Abstinence and you |

|

|

| 10. | Correct condom use |

|

|

| 11. | Talking With Your Partner |

|

|

| 12. | Moving toward your future |

|

|

aThe letters refer to the activity in the module that addresses the variable listed.

Pilot testing

Before implementing the HIV risk-reduction intervention and the health-promotion attention-control intervention in the main trial, we conducted three pilot tests. Each pilot study was a RCT, with learners randomly assigned to the six-session HIV risk-reduction intervention or the six-session health-promotion attention-control intervention based on computer-generated random number sequences. Co-facilitators with extensive experience implementing HIV/STD and health-promotion curricula in the United States conducted the first pilot in English in Mdantsane, and pairs of isiXhosa-speaking male and female adults observed. We subsequently trained these isiXhosa-speaking adults to serve as co-facilitators conducting pilot tests in isiXhosa in Berlin and in Mdantsane. Sexual matters are taboo within amaXhosa culture and consequently we were concerned about parents’ reactions to the interventions. To assess their reactions, the last take-home assignment in the first pilot test of the interventions included a brief questionnaire for parents to complete.

Facilitator training

In the main trial, we trained as co-facilitators 21 women and 22 men aged 27–56 years (mean = 42) from the community who were bilingual in English and isiXhosa in September 2004. Their education ranged from a technical school degree to a Master’s degree (median = a Bachelor’s degree); 65% had worked as teachers and 63% had implemented HIV education. We randomly assigned them to receive an 8-day training to implement ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ or the health-promotion control intervention, which randomized the facilitators’ characteristics across the interventions. Trainers modeled the interventions, and facilitators learned the background content of their intervention, the design and methodology of the study, the theoretical framework and the skills to implement the intervention with fidelity; practiced implementing their intervention and received feedback from each other, the trainers and investigators. They were trained to model gender equality in the delivery of the intervention, including the distribution of labor. Thus, we trained them not to give the impression that the female co-facilitator was assisting the male co-facilitator, but to be equal partners in the delivery of the intervention with shared responsibility. One common difficulty in implementing sexuality related interventions for adolescents is that teachers are uncomfortable with sexual material and therefore do not implement interventions with fidelity [6–9]. To ensure facilitators’ comfort with sexual terms, they had to verbalize, in both English and isiXhosa, every term they had ever heard for reproductive system body parts.

In Mdantsane and Berlin schools, learners are expected to defer to teachers, to speak only when teachers speak to them and to stand when they address a teacher in class. This poses a barrier to children’s free expression of beliefs and feelings as participants in interactive activities. Accordingly, the training stressed that the success of the intervention largely depended on the adolescents’ willingness to share their beliefs freely during the activities. We emphasized facilitation and group process over the prevailing didactic approach and employed small groups of 9–16 adolescents and circular seating of the adolescents and facilitators with everyone at the same height level. Another important part of the training was an emphasis on fidelity of implementation according to the detailed standardized manuals we gave facilitators. Overall, the training went well and facilitators received it enthusiastically (Z. Ngwane et al., submitted for publication). All 43 facilitator trainees attended each of the 8 training days.

Acceptability of the intervention

The acceptability of an intervention, how it will be received by the target population [35–38], is considered important because if an intervention is not acceptable to the population then it is unlikely that it can be taken to scale or employed widely with the population. We assessed the acceptability of the intervention to participants using measures similar to those employed in several previous intervention trials [28,29,39,40]. Learners provided ratings of ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ on 5-point Likert scales in the post-intervention assessment. We assessed the degree to which they liked the activities, felt comfortable talking and sharing their thoughts, learned from the activities and would recommend the program to others. In addition, a measure of acceptability of the take-home assignments included items on how much they liked the take-home assignments, felt comfortable with them and learned from them. We also asked the facilitators to provide ratings of the acceptability of the intervention to the participants after each session. They rated how much participants liked the activities, felt comfortable during the activities, learned from the activities and paid attention during the activities.

Results

Formative research

One theme that emerged in the adolescent focus groups was that ‘condoms destroy the sensation of meat to meat or flesh to flesh’, which is a hedonistic belief or outcome expectancy [23,41], a belief about the negative consequences of condom use for sexual enjoyment. Another behavioral belief concerned consequences of practicing abstinence. Achieving goals was seen as a reason to abstain from sex. For instance, one adolescent said, ‘telling yourself that you want to finish your schooling and you don’t have time for other things.’ Other themes were ‘condoms prevent AIDS’, which is a prevention behavioral belief [23,41], and ‘peers would approve of sex’, which is a normative belief [23,42,43]. Normative referents who disapproved of sex included parents and ancestors. There were also cultural beliefs that would have to be addressed in the intervention. For instance, participants said, ‘by having sex, you can pass on your seed’, ‘bad muthi (witchcraft) can cause AIDS’, ‘People can put a curse on you—maybe if they are jealous of you’, ‘sex with a virgin can cure AIDS’ and ‘men cannot say no to sex’. Participants suggested that girls faced risk of sexual coercion. To reduce this risk, they said, girls should never stay alone in the house, walk alone at night or accept anything from a man.

A theme that emerged in the parent groups was that parents find it difficult to talk to their children about sex. A father said, ‘Truly speaking, it is very difficult for us to talk about these things with our children, as Black people we don’t sit down with children and discuss sex’. A mother said, ‘I cannot sit down with my child and talk about sex’. Parents also mentioned age–discordant relationships. One mother said, ‘The girls don’t [use condoms] because they sleep with older men and the men don’t use condoms because they think to themselves the girl is still young and as a result is free of diseases’. This suggests that the intervention should address age–discordant relationships and the gender power imbalance common in such relationships.

Consistent with the parents’ comments, the teachers said ‘parents are uncomfortable talking to children about sex’ and ‘parents would say it’s not their culture to tell the child about things that involve sex’. The teachers also raised the issue of intergenerational sex saying: ‘Because of poverty, if I am a taxi man always having cash, I would buy things for these children and in return would expect her to give me her body’. When asked why children do not use condoms, the teachers said, ‘They say you can’t eat a sweet with its paper so they want to taste the original thing’.

Pilot testing

Of the 30 learners, 27 returned their parents’ questionnaire on reactions to the intervention included in the last take-home assignment in the first pilot test of the intervention, and none of the parents had negative comments. Here are some examples of their comments: ‘The program deals with things that are happening in a kids’ life and gives them in-depth knowledge/information’. ‘It teaches our children about protecting themselves and knowing how to say “no” when they are pressured by friends’. ‘It gives children and parents knowledge about them growing up’. ‘It teaches parents to talk to their children about things that are not easy to talk about’. ‘I was so ashamed to speak to my child about condoms, sex, periods, etc., so guys thanks. You started the way, so I am going to follow your footsteps’. A parent of a child in the health control intervention said, ‘Good things are about how to take care for themselves and other people in their community. It also develop the child as a whole and bout how they must eat healthy food’.

Acceptability of the intervention

Participants’ ratings of ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ were high. As shown in Table III, the mean ratings indicated that the learners liked the activities, felt very comfortable talking and sharing their thoughts in the group, learned a lot from the activities and would recommend the program to others. Girls’ ratings of liking and learning from the intervention activities were significantly higher than the ratings of boys. Ratings of the acceptability of the take-home assignments were also high. Similarly, facilitators’ ratings of how much participants liked the activities, felt comfortable during the activities and learned from the activities were high (Table IV). There were significant differences among the six sessions in these facilitator ratings. Significant Bonferroni-adjusted linear contrasts (Ps < 0.002) indicated that the ratings increased over the six sessions. The facilitators also rated the participants as attentive to the activities, but these ratings did not vary by session. An objective indicator of the learners’ positive view of the intervention is the adolescents’ high rate of attendance, which did not vary by gender [10]. All adolescents attended Session 1, and 97.0–98.6% attended Sessions 2–6.

Table III.

Learners’ mean (standard deviation) ratings of the acceptability of the ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention, South Africa, by sex

| Variable | All participants (N = 556) | Boys (N = 252) | Girls (N = 304) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liked the activities | 4.73 (0.42) | 4.61 (0.48) | 4.83 (0.31) | <0.0001 |

| Comfortable with the activities | 4.65 (0.63) | 4.59 (0.66) | 4.69 (0.60) | 0.0711 |

| Learned from the activities | 4.77 (0.47) | 4.58 (0.57) | 4.92 (0.28) | <0.0001 |

| Would recommend to others | 4.87 (0.40) | 4.85 (0.43) | 4.88 (0.38) | 0.3081 |

| Acceptability of the take-home assignments | 4.86 (0.33) | 4.84 (0.39) | 4.88 (0.26) | 0.1468 |

Notes: P-value is the significance probabilities for the t-test of mean differences by sex. Ratings were on 5-point scales where higher scores indicated greater agreement with the statement. Acceptability of the take-home assignments is a composite of three questions: how much they liked the assignments, felt comfortable with them and learned from them.

Table IV.

Facilitators’ (N = 21) mean (standard deviation) ratings of the acceptability of the ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention to isiXhosa-speaking adolescents, South Africa, by intervention session

| Variable | Intervention session |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | P-value | |

| Liked the activities | 4.79 (0.42) | 4.66 (0.48) | 4.67 (0.53) | 4.86 (0.35) | 4.78 (0.42) | 4.86 (0.35) | 4.90 (0.31) | 0.0005 |

| Comfortable with the activities | 4.55 (0.58) | 4.25 (0.66) | 4.45 (0.68) | 4.52 (0.55) | 4.68 (0.47) | 4.63 (0.49) | 4.75 (0.43) | <0.0001 |

| Learned from the activities | 4.64 (0.50) | 4.54 (0.55) | 4.48 (0.58) | 4.65 (0.48) | 4.68 (0.47) | 4.72 (0.45) | 4.75 (0.43) | 0.0044 |

| Attentive to lessons | 4.66 (0.50) | 4.69 (0.49) | 4.61 (0.57) | 4.65 (0.51) | 4.64 (0.48) | 4.63 (0.49) | 4.73 (0.45) | 0.7226 |

Notes: P-value is the significance probabilities for the F-test of mean difference among the six intervention sessions. Ratings were on 5-point scales where higher scores indicated greater agreement with the statement.

Discussion

HIV continues to have a devastating impact in South Africa. Addressing this problem requires the identification of behavior-change interventions for all populations that engage in risk behaviors [6]. Such interventions are likely to be most efficacious if they are acceptable to the target population and address the mediators of behavior change in that population. One important population is adolescents, and schools are an important venue in which to expose adolescents to risk-reduction messages. Schools provide an opportunity to reach most adolescents before the onset of sexual activity and before patterns of sexual-risk behavior become habitual and more resistant to change.

This article described the steps taken to ensure that ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ would be acceptable and that it would influence mediators of behavior change. We collected relevant information about the context, culture and dynamics of the sexual behavior of South African adolescents. We integrated this information with the social cognitive theory and the reasoned action approach. In the intervention, we employed a series of engaging interactive activities to increase theory-relevant beliefs supporting abstinence, condom use and limiting sexual partners and to increase skill and self-efficacy to negotiate and practice abstinence and condom use. Some of the activities were created specifically for isiXhosa-speaking South African adolescents to address issues identified in formative research, whereas others were adapted from appropriate activities used in successful interventions with adolescents in the United States.

Several sources of evidence suggest that the resulting intervention was acceptable to the target population. First, the participants gave the intervention high marks: their ratings of the intervention indicated they liked it, were comfortable with the activities, felt they learned a lot and would recommend it to others. Consonant with these ratings were the facilitators’ perceptions that the learners liked the intervention, felt comfortable during the activities, learned a lot and were attentive. In addition, the participants gave favorable ratings of the take-home assignments they completed with their parents. The high attendance rates provided an objective indicator of acceptability because the learners chose to attend the intervention, which we offered during their extracurricular activity period when they could have engaged in other activities. Finally, at least a modicum of evidence of acceptability is provided by the high regard with which the parents in the first pilot study held the intervention.

‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ should be viewed in the context of other interventions evaluated in sub-Saharan Africa, especially South Africa. Like several HIV risk-reduction interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, it drew upon social cognitive theories [44–48]. One novel component of the intervention was the comic workbooks and the distinctive way in which the intervention employed them. As far as we know, no other interventions targeting adolescents in South Africa have employed comic workbooks. We used them to introduce a variety of issues and to prepare the learners for the skill-building role-plays. Another novel aspect of this intervention was the way in which we involved parents. None of the reviews of HIV risk-reduction interventions in sub-Saharan Africa cited interventions that included parents [7–9]. Indeed, we are aware of only one intervention study in South Africa that tried to involve parents, but that study intervened only with parents of adolescents, not with the adolescents and did not report effects on the adolescents’ behavior [49]. Similarly, a study in Kenya intervened with parents, but did not report sexual behavior outcomes for adolescents [50]. We included parents in an innovative way. Rather than trying to engage parents by having them attend intervention sessions, we involved them through take-home assignments and prepared the children to engage in communication with their parents. A third novel feature of the intervention is that it targeted young adolescents in the earliest stages of sexual involvement. The children who received our intervention were younger than the participants in any other HIV risk-reduction intervention trial conducted with adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, and only 3.3% of them reported sexual experience. Thus, this is the first intervention in South Africa to focus on primary prevention of sexual risk behavior before habitual patterns of sexual behavior have been established. Another unique feature of this intervention was the use of male and female co-facilitators who modeled gender equality as they implemented the interventions.

Lessons learned

For those who would design and implement interventions with adolescents, particularly young adolescents, in South Africa, this research has highlighted several challenges, including the taboo regarding sexual matters, gender appropriateness of discussions, lack of electricity and didactic styles of teaching. We found that many potential facilitators were very uncomfortable with sexuality and terms for sexual and reproductive body parts. This dovetails with studies reporting implementation difficulties centering on intervention facilitators, typically teachers, who did not implement aspects of the interventions concerning condom use [6–9]. In our study, the majority of the facilitators were former teachers. We addressed this problem in two ways. First, in our selection of facilitators, we used performance-based criteria in which candidates had to demonstrate an intervention activity, condom demonstration, and screened out those who seemed very uncomfortable handling the condom or doing the activity. Second, during the facilitator training, we tried to build comfort with sexual words by ensuring that the facilitator trainees had to use them repeatedly, which is a common technique for increasing comfort with sexual matters.

In a similar vein, parents were uncomfortable discussing sexual matters with their children. We addressed this with a series of take-home assignments on increasingly sensitive topics to make parents more comfortable talking to their children about reducing the children’s sexual risks and increasing children’s self-efficacy to communicate with their parents. The taboo regarding sexual matters also came up when we wanted to provide knowledge about puberty and reproductive anatomy, which is necessary in interventions with young adolescents. It was considered culturally inappropriate to cover this material in mixed-gender groups; accordingly, we addressed it in single-gender groups led by the same-gender facilitator. This solution, however, may not always be available in schools. If the teacher is a female and no male teacher is available, for instance, she may have to cover the material with both girls and boys. In such circumstances, it might make sense to cover the material with the girls and boys separately.

Another challenge is lack of electricity in some settings, which means it may not be possible to use technology, including televisions, in the interventions. The use of comic workbooks, as done here, is a way of achieving many of goals that are commonly addressed with video, and it has the additional benefit of affording an opportunity for the children through the experience of reading the dialog before the group to gain confidence to engage in role playing later in the curriculum.

Finally, the didactic style of teaching in many schools in sub-Saharan Africa possess a challenge in that the children are not accustomed to participatory learning activities, which are important for highlighting the beliefs of the learners and for skill building. Getting learners to participate in such activities is a challenge. A related challenge is getting the facilitators to implement the activities in an interactive way rather than in a didactic way. We tried to overcome this barrier by the use of a circular setting arrangement with the facilitators seated with the adolescents. The trouble is that facilitators might implement the intervention with themselves outside the circle behind a desk, or they might stand while the participants are seated, or they may fail to arrange participants in a circle. These deviations do not encourage the free participation that is important for the adolescents to get as much as possible out of the intervention experience. To address this, monitoring, supervision and debriefing of facilitators with re-training when necessary can make a big difference in whether the intervention is delivered properly.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ‘Let Us Protect Our Future’ intervention’s strengths include using behavior-change theory and formative research in its development to ensure that the intervention was both theoretically grounded and culturally congruent, using appropriate activities adapted from other efficacious interventions, and creating novel activities specifically for young sexually inexperienced isiXhosa-speaking adolescents that addressed issues identified in the formative research. On the other hand, the use of self-reports for the acceptability data and the sexual behavior outcomes in evaluating the intervention is a limitation because social desirability response bias can affect self-reports. We tried to mitigate the influence of such bias by assuring the participants confidentiality, encouraging them to respond honestly so that the results, which would be used to develop programming for other youths like themselves, would be accurate, and employing as data collectors, not the facilitators who implemented their group, but other research staff members. Another limitation is that we do not know whether the results generalize to other populations of adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa.

Finally, systematic reviews of HIV/STI prevention intervention studies targeting young people in sub-Saharan Africa have found significant effects on non-behavioral outcomes, including self-efficacy, knowledge, beliefs and intentions, but limited effects on sexual-risk behaviors [6,7,9] and have highlighted the need for greater attention to implementation difficulties. Viewed in this context, the ‘Let Us Protect Our Future!’ intervention is promising: it reduced both self-reported sexual risk behavior and mediators of such behavior; it surmounted potential implementation difficulties and it was acceptable to young adolescents, engaging and retaining them [10,14,24]. Despite the enumerated limitations, then, this article suggests that Let’s Us Protect Our Future! should be considered for use with young adolescents in South Africa.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of Dr Nicole Hewitt, Dr Shasta Jones, Dr Monde Makiwane, Ms Pretty Ndyebi, Dr G. Anita Heeren, Ms Janet Hsu and Ms Jingwen Zhang. They also appreciate the contributions of facilitators, facilitator trainers, adolescents, parents, teachers, principals and school governing board members.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01MH065867). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2012. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_with_annexes_en.pdf. Accessed: 16 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2008. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cates W. HPTN 052 and the future of HIV treatment and prevention. Lancet. 2011;378:224–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klausner JD, Serenata C, O’Bra H, et al. Scale-up and continuation of antiretroviral therapy in South African treatment programs, 2005–2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:292–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182067d99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wouters E, Heunis C, Michielsen J, et al. The long road to universal antiretroviral treatment coverage in South Africa. Future Virol. 2011;6:801–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michielsen K, Chersich MF, Luchters S, et al. Effectiveness of HIV prevention for youth in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials. AIDS. 2010;24:1193–202. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283384791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul-Ebhohimhen VA, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER. A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison A, Newell ML, Imrie J, et al. HIV prevention for South African youth: which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picot J, Shepherd J, Kavanagh J, et al. Behavioural interventions for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in young people aged 13–19 years: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:495–512. doi: 10.1093/her/cys014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, et al. School-based randomized controlled trial of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for South African adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:923–9. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, et al. Cognitive-behavioural health-promotion intervention increases fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity among South African adolescents: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health. 2011;26:167–85. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.531573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook T, Campbell D. Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis for Field Settings. Chicago: Houghton Mifflin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindquist R, Wyman JF, Talley KMC, et al. Design of control-group conditions in clinical trials of behavioral interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:214–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Leary A, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, et al. Moderation and mediation of an effective HIV risk-reduction intervention for South African adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:181–91. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9375-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: WH Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior. Boston: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection. In: Mays VM, Albee GW, Schneider SF, editors. Primary Prevention of AIDS: Psychological Approaches. Newbury Park: Sage; 1989. pp. 128–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivis A, Sheeran P, Armitage C. Intention versus identification as determinants of adolescents’ health behaviours: evidence and correlates. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1128–42. doi: 10.1080/08870440903427365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Heeren GA, Ngwane Z, et al. Theory of planned behaviour predictors of intention to use condoms among Xhosa adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19:677–84. doi: 10.1080/09540120601084308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jemmott JB., 3rd The reasoned action approach in HIV risk-reduction strategies for adolescents. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2012;640:150–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, et al. Effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for adolescents when implemented by community-based organizations: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:720–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Efficacy of a theory-based abstinence-only intervention over 24 months: a randomized controlled trial with young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:152–9. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS. A randomized controlled trial testing an HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:772–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, et al. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:440–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279:1529–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37:122–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB., 3rd . Promoting Health Among Teens! Abstinence-Only. New York: Select Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, 3rd, McCaffree K. Making Proud Choices! A Safer-Sex Approach to HIV/STDs and Teen Pregnancy Prevention. New York: Select Media; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, 3rd, McCaffree K. Be Proud! Be Responsible! Strategies to Empower Youth to Reduce their Risk for HIV/AIDS. New York: Select Media; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, 3rd, McCaffree K. Making a Difference! An Abstinence Approach to HIV, STDs and Teen Pregnancy Prevention. New York: Select Media; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayala GX, Elder JP. Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioral and social interventions to the target population. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(Suppl 1):S69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery ET, Cheng H, van der Straten A, et al. Acceptability and use of the diaphragm and Replens lubricant gel for HIV prevention in Southern Africa. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:629–38. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9609-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montgomery ET, Woodsong C, Musara P, et al. An acceptability and safety study of the Duet cervical barrier and gel delivery system in Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangunkusumo R, Brug J, Duisterhout J, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and quality of Internet-administered adolescent health promotion in a preventive-care setting. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:1–13. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among black male adolescents: effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. Am J Pub Health. 1992;82:372–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, et al. Reducing HIV risk-associated sexual behavior among African American adolescents: testing the generality of intervention effects. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:161–87. doi: 10.1007/BF02503158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Spears H, et al. Self-efficacy, hedonistic expectancies, and condom-use intentions among inner-city black adolescent women: a social cognitive approach to AIDS risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:512–9. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Igumbor OJ, Pengpid S, Obi CL. Effect of exposure to clinic-based health education interventions on behavioural intention to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. SAHARA J. 2006;3:394–402. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2006.9724865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heeren GA, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Mandeya A, et al. Sub-Saharan African university students’ beliefs about condoms, condom-use intention, and subsequent condom use: a prospective study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:268–76. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9415-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karnell AP, Cupp PK, Zimmerman RS, et al. Efficacy of an American alcohol and HIV prevention curriculum adapted for use in South Africa: results of a pilot study in five township schools. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:295–310. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.4.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanton BF, Li X, Kahihuata J, et al. Increased protected sex and abstinence among Namibian youth following a HIV risk-reduction intervention: a randomized, longitudinal study. AIDS. 1998;12:2473–80. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, et al. Theory-based HIV risk reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:727–33. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145849.35655.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heeren GA, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Ngwane Z, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of an HIV risk-reduction intervention for sub-Saharan African university students. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1105–15. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, et al. Neighborhood-based randomized controlled trial of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for South African men. Am J Pub Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301578. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bell CC, Bhana A, Petersen I, et al. Building protective factors to offset sexually risky behaviors among black youths: a randomized control trial. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:936–44. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vandenhoudt H, Miller KS, Ochura J, et al. Evaluation of a U.S. evidence-based parenting intervention in rural western Kenya: from parents matter! to families matter! AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22:328–43. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]