Abstract

In the United States, youth of 13–24 years account for nearly a quarter of all new HIV infections, with almost 1000 young men and women being infected per month. Young women account for 20% of those new infections. This article describes the design, feasibility, and acceptability of a secondary prevention empowerment intervention for young women living with HIV entitled EVOLUTION: Young Women Taking Charge and Growing Stronger. The nine session intervention aimed to reduce secondary transmission by enhancing social and behavioral skills and knowledge pertaining to young women's physical, social, emotional, and sexual well-being, while addressing the moderating factors such as sexual inequality and power imbalances. Process evaluation data suggest that EVOLUTION is a highly acceptable and feasible intervention for young women living with HIV. Participants reported enjoying both the structure and comprehensive nature of the intervention. Both participants and interventionists reported that the intervention was highly relevant to the lives of young women living with HIV since it not only provided opportunities for them to broaden their knowledge and risk reduction skills in HIV, but it also addressed important areas that impact their daily lives such as stressors, relationships, and their emotional and social well-being. Thus, this study demonstrates that providing a gender-specific, comprehensive group-based empowerment intervention for young women living with HIV appears to be both feasible and acceptable.

Introduction

Nearly a quarter of all new HIV infections in the United States occur among youth ages 13–24, with almost 1000 young men and women being infected per month.1 While young women account for only 20% of those new infections, the number of young women being infected each year is still considerable.1 Young women account for almost half of AIDS cases among those aged 13–19 and one third of AIDS cases among young adults aged 20–24.1 In 2009, HIV was the leading cause of death for women in the United States between the ages of 25 and 34.2 The primary mode of infection for female adolescents and young adults is sexual activity with a male. Even after their diagnosis, some young women continue to engage in risky sexual behavior that not only places their sexual partners at risk of infection, but also places them at higher risk for secondary sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV re-infection.3,4 Sturdevant and colleagues found that young women living with HIV had more lifetime sexual partners and that the age difference of their sexual partners was greater than that of young uninfected women.5 They also found that the greater age difference among sexual partners was associated with less condom use.5 This participation in sexual risk behaviors, coupled with limited behavioral skills to negotiate safer sex underscores the urgent need for secondary prevention interventions for this population.6

Unlike young men, young women face gender power imbalances at the relational, social, and institutional level that increase their social and behavioral risk for acquiring HIV and passing on HIV to their sexual partners.7 Therefore, in order to effectively address HIV prevention among young women, interventions must address the power imbalances and gender inequalities that ultimately impact young women's behavior.7

Despite the need for interventions tailored to the unique life circumstances of young women living with HIV (YWLH), there have not been any published secondary prevention interventions to date designed specifically for this population.3,8–10 In a qualitative study by Hosek and colleagues3 of what young women wanted from HIV interventions, YWLH asked for a comprehensive, gender-specific intervention that went beyond traditional HIV/AIDS prevention education to address the psychological and social issues that impact their lives. These findings support current recommendations for behavioral interventions for people living with HIV that address the moderating factors of sexual risk behavior and treatment adherence such as social support, mental health, and poverty.9,11 Therefore, secondary prevention interventions for YWLH have the potential to provide skills to decrease sexual risk behavior (e.g., abstinence, partner reduction, consistent condom use, and HIV status disclosure) and to address some of the social, relational, and personal factors that initially placed them at risk for HIV including gender roles, cultural norms, self-efficacy, and self-confidence.4,9,12–15 Addressing these moderating factors may increase the effectiveness of a secondary prevention intervention while also making the intervention more relevant to YWLH.

EVOLUTION: Young Women Taking Charge and Growing Stronger is a secondary prevention empowerment intervention for young women living with HIV. The experimental intervention aims to reduce risk of HIV transmission to participants' sexual partners; reduce participants' risk of HIV re-infection or co-infection with another STI; and increase participants' social and behavioral skills to better address the issues young women living with HIV face. EVOLUTION is one of the first secondary prevention interventions in the literature that was developed and piloted exclusively for young women ages 16–24 living with HIV.

Conducted through the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN), EVOLUTION was piloted in two iterations at clinical sites in Baltimore, Maryland, Chicago, Illinois, and Tampa, Florida. The first iteration of the study served as practice for sites and enabled the protocol team to revise the intervention's content and structure based on the process evaluation data and feedback from the sites. The second iteration then piloted the adapted experimental intervention with different participants using a two-arm, randomized controlled trial design with a health-focused control condition that was matched for time and attention. This article presents a detailed description of the second iteration of the intervention, along with its respective data regarding the feasibility and acceptability of enrolling and retaining young women living with HIV into a secondary prevention empowerment intervention.

Methods

Sample

Young women were eligible to participate if they were documented to be HIV-positive, between the ages of 16–24 years, received medical care at one of the three participating ATN sites or their community partners, and understood both written and spoken English at approximately the 8th grade level. Participants could be either behaviorally or perinatally infected. Young women were excluded if they demonstrated active, serious psychiatric symptoms that would impair their ability to meet the study requirements, or were visibly distraught and/or intoxicated at the time of study enrollment.

Study coordinators at the clinical sites prescreened charts for potentially eligible participants. A total of 79 patient charts were reviewed over the course of the first and second iteration of the study. Eight subjects were ineligible, five due to age, two due the inability to be located, and one due to an existing mental health issue that would have impaired her ability to meet study requirements. Of the 71 potentially eligible participants, four were approached but not screened due to lack of interest in the study. Sixty seven were screened and found to be eligible, but two did not enroll because of scheduling conflict or lack of interest in the study. A total of 65 young women were enrolled in the trial, 22 in the first iteration and 43 in the second iteration.

Of the 43 young women enrolled in the second iteration, twenty-two young women were enrolled in the experimental intervention arm (EVOLUTION). The majority of participants (77.3%) were aged 19–24 (mean age=20.55) and identified as African American (86.4%) (Table 1). Forty-one percent of participants had less than a high school education and were currently in school. Most participants identified as straight (86.4%); 12.5% identified as bisexual. Half of the young women reported past pregnancies. Two participants were diagnosed with HIV in the 12 months prior to enrollment, and more than half (59.1%) were currently taking antiretroviral (ARV) medications.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics

| Intervention(N=22) N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 16–18 | 5 (22.7%) |

| 19–24 | 17 (77.3%) |

| Race | |

| African American | 19 (86.4%) |

| White, mixed and other | 3 (13.6%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Less than high school | 9 (40.9%) |

| High school/GED/college/technical | 13 (59.1%) |

| Currently in school | |

| No | 8 (36.4%) |

| Yes | 11 (50.0%) |

| No, graduated | 3 (13.6%) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight | 19 (86.4%) |

| Bisexual | 3 (13.6%) |

| Pregnancy history | |

| Never | 11 (50%) |

| Time since diagnosis | |

| 12 months and under | 2 (9.1%) |

| Taking ARV medications | |

| Yes | 13 (59.1%) |

Intervention content

EVOLUTION is a comprehensive intervention, grounded in the Theory of Gender and Power16 that aims to empower YWLH by enhancing skills and knowledge pertaining to the physical, social, emotional, and sexual self, and addressing moderating factors that increase women's vulnerability, such as sexual inequality and power imbalances. The primary empowerment focus for the intervention was empowerment at the individual level of analysis, which includes cognitions, emotions, and behaviors, and is often experienced as a sense of control, a critical awareness of one's social and physical environment, and action to exercise control.17–19 The content areas and framework of EVOLUTION were developed from focus groups collected by Hosek and colleagues3 with young women living with HIV. Based on the qualitative findings and an extensive literature review of existing primary and secondary HIV interventions for women, a draft curriculum was outlined. Five young women living with HIV were then nominated from local community-based organizations and recruited by the research team to establish a Youth Advisory Team (YAT). The YAT met weekly during the curriculum development to provide feedback on the content, wording, and formatting of the materials to ensure the intervention was acceptable and developmentally appropriate.3 Once the entire curriculum was developed, the first iteration of the experimental intervention (n=22) was piloted at the three participating sites. Feedback from the interventionists' logs and participant session and program evaluation forms were then brought back to the YAT and the research team so that edits to the content and format of the intervention could be made accordingly. All feedback was discussed. Changes were incorporated if the majority of participants and/or interventionists reported similar suggestions or the research team and YAT felt that the suggestion was reasonable. An overview of the final content areas of EVOLUTION and each session's goals are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of EVOLUTION

| Session | Goals |

|---|---|

| Individual Session 1— Introduction | • Develop rapport with participant and introduce EVOLUTION |

| Group Session 1— Empower 101, Because You Are Worth It | • Develop rapport within the group |

| • Create a safe and secure space for participants | |

| • Present the intervention theory and concept | |

| • Establish intervention domains: emotional, social, sexual and physical | |

| • Address and acknowledge participants' past and introduce the topic of forgiveness as a tool for healing | |

| Group Session 2— Being “Positive” | • Develop and build knowledge in the physical, emotional and sexual domains |

| • Define what it means to be a woman with and without HIV | |

| • Explore sexuality within the context of being HIV positive | |

| • Identify barriers and facilitators to being a healthy sexual being | |

| Group Session 3— What it Means to Be a Woman with HIV | • Discuss the importance of self-esteem |

| • Conduct self-esteem activities that explore the dimensions of one's self | |

| • Work on questioning one's negative beliefs and building a balanced view of oneself | |

| • Identify barriers and facilitators to safe disclosure | |

| • Examine the role of stigma in one's life and how to overcome it. | |

| Group Session 4— Living With Your Emotions | • Develop skills and build knowledge in the emotional and social domain |

| • Identify stressors and develop ways to better cope with stress, uncover automatic thoughts and challenge and combat negative thinking | |

| • Define, anger, its different types and learn alternatives to anger | |

| Group Session 5— Relationships 101 | • Develop skills and build knowledge in the social domain |

| • Recognize the differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships | |

| • Explore ways to identify and deal with an unhealthy relationship | |

| • Learn how to effectively communicate feelings, wants and desires | |

| Group Session 6— Relationships 102 and Alcohol and Drugs | • Develop skills and build knowledge in the social and sexual domain |

| • Practice good communication and listening skills | |

| • Recognize one's sexual partner network and how quickly STIs can spread | |

| • Examine how drugs and alcohol can impact one's life | |

| • Set goals for the future | |

| • Practice methods to reduce tension | |

| Group Session 7— Empower 102: Living Your Best Life | • Wrap up the EVOLUTION program |

| • Develop plans and strategies to continue growing and evolving | |

| • Discuss what to do when there is or there is a possibility of relapse | |

| Individual Session 2— Checking In and Future Planning | • Go over the program in its entirety |

| • Finalize EVOLUTION Action Plan | |

| • Make referrals as necessary. |

Both the experimental intervention and the health-focused control condition in the second iteration consisted of seven group sessions and two individual sessions. Each session lasted between 2 and 3 h and occurred approximately every week for 9 weeks.

Procedures and measures

The study was approved by the participating clinical sites' respective institutional review boards prior to study implementation, and written informed consent was provided by all of the participants. Each group was comprised of 6–8 young women, and participants were provided incentives for participation according to each site's guidelines for both the first and second iteration. Interventionists hired at the sites were female, had mental health training and previous experience facilitating individual and group sessions with adolescents. All sessions during this study were digitally recorded and reviewed by members of the research team to assess for competence and adherence to the protocol.

Evaluation data for both the first and second iteration were collected using the Session Evaluation Forms (SEF) completed at the end of each intervention session and the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) that was completed at the end of the intervention. The SEF is a brief 12-item questionnaire that included 10 items on a 4-point response scale aimed at eliciting information about the participant's experience with the session (i.e., was the session interesting, was it relevant to their life, did they learn from the session).20 Two open-ended items queried participants about what was most useful and what they would like to change about the session. The CSQ-8 was used at the completion of the intervention to assess the participant's satisfaction with the intervention, including the procedures, quality and quantity of service, outcome, and general satisfaction.21 Feasibility data included attendance across the intervention sessions and attrition rates.

Interviews from the three interventionists from the second iteration of the study were conducted to gather further data regarding acceptability and feasibility. These individual, in-depth interviews discussed the delivery of intervention's sessions and activities, including what topics and activities worked and what did not work, the interventionists' perceptions of acceptability, comprehension, and engagement among the participants and the challenges interventionists faced in implementing the intervention and areas in need of further modification.

Feasibility and acceptability analysis

The proportion of study sessions completed and the proportion of participants retained in the study were computed. Responses from the SEF and CSQ-8 measured the delivery of intervention components and participants' engagement of the content, as well as their perceptions of intervention acceptability. Transcripts from all three interventionists' exit interviews captured the interventionists' critique of the intervention, including their thoughts and views on the critical components of the intervention and areas or activities of the intervention in need of further revision. Data from the SEF open-ended feedback questions and transcripts from the interventionist exit interviews were compiled and reviewed by the research team members. Themes and codes were then identified and applied to all of the transcripts. The research team then met, via conference call, to review findings and complete final analysis. The acceptability analysis data presented here is limited to those participants who were assigned to the intervention condition and the three interventionists involved in the second iteration. Intervention outcome analyses will be conducted separately and reported elsewhere.

Results

Feasibility

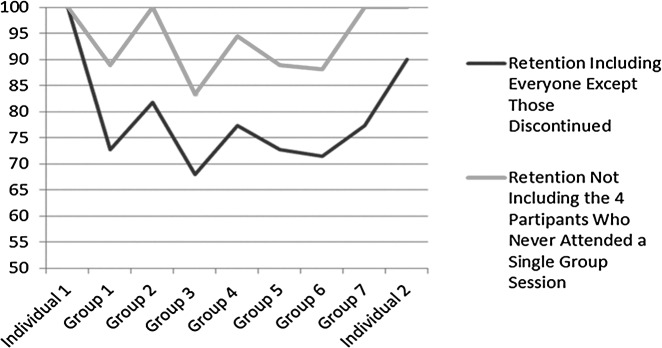

Of the 22 young women enrolled in the experimental intervention arm during the second iteration, two were discontinued prematurely (one was incarcerated, and one was discontinued due to group misconduct). Retention in the experimental intervention condition was 77.8% overall. However, when the four participants who only attended the first individual session and subsequently missed all group sessions are taken out of the analysis, retention for the overall experimental intervention is 93.1%. Retention in the group sessions, among those participants who attended at least one group session, ranged from 81.3% to 100% for each session (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Percentage distribution of study participants' attendance in group and individual intervention sessions.

Acceptability

Responses on the CSQ-8, illustrated in Table 3, demonstrated high levels of participant satisfaction with the experimental intervention overall. The quality of the experimental intervention was rated between good and excellent, with 81% rating it as excellent. Almost all participants (87.5%) reported that they definitely got what they wanted from the intervention and that they were very satisfied with the program. Eighty-one percent of participants felt that the program helped them to manage problems more effectively and stated that almost all their needs had been met by the program. When asked if the participants would recommend EVOLUTION to others and would be willing to come back to the program, almost all (93.8%) agreed.

Table 3.

Results of Study Participants' Client Satisfaction Questionnaire for the EVOLUTION Program Overall

| Item | N (%) |

|---|---|

| How would you rate the quality of our program? | |

| Excellent | 13 (81%) |

| Good | 3 (19%) |

| Fair | 0 (0%) |

| Poor | 0 (0%) |

| Did you get what you wanted from our program? | |

| Yes, definitely | 14 (87.5%) |

| Yes, generally | 2 (12.5%) |

| No, not really | 0 (0%) |

| No, definitely | 0 (0%) |

| To what extent has our program met your needs? | |

| Almost all of my needs have been met | 12 (75%) |

| Most of my needs have been met | 4 (25%) |

| Only a few of my needs have been met | 0 (0%) |

| None of my needs have been met | 0 (0%) |

| If a friend were in need of similar help, would you recommend our program? | |

| Yes, definitely | 15 (93.8%) |

| Yes, I think so | 1 (6.2%) |

| No, I don't think so | 0 (0%) |

| No, definitely | 0 (0%) |

| Has our program helped you to deal more effectively with your problems? | |

| Yes, they helped a great deal | 13 (81%) |

| Yes, they helped | 3 (19%) |

| No, they didn't really help | 0 (0%) |

| No, they seemed to make things worse | 0 (0%) |

| In an overall general sense, how satisfied were you with our program? | |

| Very satisfied | 13 (81%) |

| Mostly satisfied | 3 (19%) |

| Indifferent or mildly dissatisfied | 0 (0%) |

| Quite dissatisfied | 0 (0%) |

| If you were to seek help again, would you be come back to our program? | |

| Yes, definitely | 15 (93.8%) |

| Yes, I think so | 1 (6.2%) |

| No, I don't think so | 0 (0%) |

| No, definitely | 0 (0%) |

As seen in Table 4, the Session Evaluation Forms also demonstrated high levels of acceptability with the mean and standard deviation for each of the 10 constructs across all sessions ranging from 1.2–1.3 and 0.43–0.50, respectively, with 1=strongly agreed and 2=agreed. Participants either strongly agreed or agreed when asked whether the content was relevant to their lives, whether they learned a lot from each individual session, and whether they could apply what they learned from the session to their lives.

Table 4.

Results of Study Participants' Evaluation of Each Construct Across All Sessions

| Item | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Learned a lot | 1.24 (0.43) |

| Able to apply | 1.24 (0.44) |

| Given an opportunity to participate | 1.30 (0.46) |

| Well organized | 1.27 (0.46) |

| Interesting | 1.26 (0.44) |

| Presenter stimulated my interest | 1.29 (0.50) |

| Relevant | 1.26 (0.45) |

| Enjoyable | 1.31 (0.48) |

| Would recommend to others | 1.30 (0.46) |

| Comfortable participating | 1.27 (0.48) |

1=Strongly agree; 2=agree; 3=disagree; 4=disagree.

Participants were able to provide feedback about what was most useful and what they would like to change about the sessions in two open-ended items at the end of each Session Evaluation Form. Interventionists' critique of the experimental intervention was captured during their individual, in-depth interviews.

Themes elicited from participants' and interventionists' feedback could be categorized into intervention (a) structure and format, (b) content, and (c) areas in need of improvement.

Structure and format

There were six primary aspects of the experimental intervention structure and format that participants enjoyed and found useful: (a) group setting, (b) ground rules, (c) participant contract, (d) personal reflection and goal setting, (e) action plan calendar, and (f ) linkage-to-care. Participants noted throughout the intervention how much they enjoyed the group setting and that being with other young women like them created an environment where they could share and discuss their lives. As one young women said, “it was nice to hear about other girls in my predicament.” Participants also expressed how they appreciated the ground rules which were clearly defined at the outset of the intervention and emphasized confidentiality, respect, and safety of all group members. As one participant pointed out: “rules make every situation better.” In addition, they liked the participant contract that emphasized the importance of each participant's personal commitment to addressing her own emotional, social, sexual, and physical health. One participant noted that the contract not only addressed what the intervention would focus on but what it would “expect out of me.” Another young woman stated “I like that everything is planned out to help me better myself.” Activities that involved personal reflection and goal setting (short and long term goals) in different domains (emotional, social, physical, and sexual) of participants' lives were also viewed as beneficial. One participant stated the intervention overall “made me think about my life and past and present and long-term goals that I want to complete.” Another young woman said the personal reflection and goal setting in the different domains gave her an opportunity “to go where I don't usually go.” One of the most popular and useful sessions according to participant feedback was the final individual session where participants reviewed lessons learned and mapped out their individualized emotional, social, physical, and sexual health goals over the next 6 months. The young women's sentiment was that they liked “the fact that we looked back at everything that we discussed and learned from previous activities” and that “it was nice to know of my achievements.” Participants also reported that they liked having someone to work with them to develop a “game plan” in order to reach their goals. As one young women stated, “I liked being able to cooperatively go over my goals and get feedback” and another felt “it was good to know the steps” ‘[she] “need[ed] to take.” The comprehensive plan with detailed strategies and steps were seen as “something necessary,” “very realistic,” applicable, and that it could “help me to best my life.” Finally, participants appreciated the linkage-to-care made possible through the interventionists' referrals because as one participant stated “it gave me help people [and a] place to go in time of need.”

There were four primary aspects of the experimental intervention structure and format that interventionists appreciated and found useful: (a) the comprehensive nature of the intervention and the relevant topics, (b) the provision of individual and group sessions, (c) group setting, and (d) schedule.

All of the interventionists felt that EVOLUTION provided young women living with HIV a needed comprehensive empowerment intervention that addressed relevant and common issues young women living with HIV face on a daily basis. They also stated that would recommend the intervention to others. As one interventionist stated, “I think it addresses some of the most important issues that the girls are facing in terms of being HIV positive and just in terms of their health in general so from the knowledge about HIV and their sexual risk to self-esteem and disclosure and those types of issues.” Interventionists felt that the program did a good job of introducing and addressing sensitive topics surrounding living with HIV such as stigma. “Even some of the activities that maybe that they were not willing to acknowledge, that things had changed since their diagnosis, I think just having those discussions are really important even if it is just planting the seeds and helping them to reinforce their beliefs that they are still strong and able to do a lot things. I felt it really hit on topics that are most important to them.”

The interventionists felt that providing an intervention that included both individual and group sessions was beneficial. According to the interventionists, the first individual session where participants were introduced to their interventionist, the intervention and its' expectations of the participants was met with a lot of excitement. The interventionists also felt that having activities that discussed the challenges and barriers to coming to a group-based intervention helped participants to overcome their concerns. One interventionist stated, “I think they were all really excited during the first individual session. That session went well. The first one they were really excited and wanted to be a part of group and start. And we talked about their reasons for wanting to come to group and the barriers and why they wouldn't want to come and I felt that the first session went well across the board and that it engaged them to come to group.” The second individual session in which the interventionist reviewed all of the sessions, provided referrals and mapped out an action plan calendar with the participants was also well received according to the interventionists. “So going over the sessions I thought went great and it was a good review for them.” However, while interventionists liked the concept of an action plan calendar with participant-driven goals for the participants to work on once the intervention ended, the interventionists had varying opinions as to whether participants were really going to implement the plan without the support of the interventionist and group. As one interventionist stated, “But for the most part the majority of the young ladies grasped it and said that they would use it in their future. And I think some of them actually would.” Another interventionist said, “I love the concept of trying to take the steps and really applying them. I just got the sense at a gut level that it really wasn't going to go anywhere.”

According to the interventionists, providing a group setting where young women living with HIV could come together and learn from one another was a benefit in and of itself. One interventionist stated, “I just feel like that it [EVOLUTION] addresses some of the most important issues that young women need to be talking about and especially with each other.” Another interventionist stated, “I think the best part of it was getting the girls here…They really enjoyed coming and it was nice to have them and it really felt like we were making a difference.” Another interventionist noted that the young women “always showed up ready to get started and enjoyed each other very much. They enjoyed getting to know each other and making those friendships.” However, it was noted that establishing a cohesive group was not always easy to achieve. One interventionist pointed out that the attitude of a few could really impact the group and not always in a positive way. “I think we had some [participants] that were there just for the incentive and [their attitude was like] if I participate I will participate, but then I think they did learn some things but it was like because of the group dynamics it kind of changed the atmosphere for learning.”

Interventionists reported that the schedule of sessions was well received since it was chosen by the participants. Interventionists felt that 2 h was a good length for each session and that anything longer might be “too long” since young women have other daily commitments such as school, work and daycare.

Content

There were eight primary themes regarding specific content areas included in the experimental intervention that participants enjoyed and found useful: (a) self-confidence and self-esteem, (b) emotional regulation, (c) stress and coping, (d) anger management, (e) healthy relationships, (f ) sexual risk reduction, (g) sexual networks, and (h) HIV disclosure.

Activities that focused on building self-confidence and self-esteem and empowering young women to see beyond their HIV status, to critically examine how men and women are valued, and imbalances in power between men and women were well received and enjoyed. As one participant stated “it [the activities] helped me want to put more effort into building myself up to do my best.” Regarding to self-esteem, one participant stated “I didn't know I didn't have much [self-esteem] now I can work on it.” Young women particularly enjoyed activities that encouraged honest introspection and self-reflection and enabled them to examine and critique their social and emotional well-being. For example, a session focused on assisting the participants with improving their emotional regulation through activities that encouraged them to identify their daily stressors, distorted thinking, and negative emotions, then develop strategies to cope with them. This session was well received by participants and the theme of introspection and self-reflection came up “It [the session] made me look at myself and my coping skills better.” Young women also enjoyed developing anger management skills as it helped them “find ways to control.” The majority of participants noted how relevant these topics were and how much the skills that they learned were needed in their lives.

Activities involving the development and maintenance of healthy relationships, including romantic relationships, were also seen as highly useful and relevant to the young women, especially given that many reported histories of abusive relationships. As one participant stated, “I enjoyed this one because I was able to take a closer look at my relationship.” Young women reported that the activities helped them identify the abuse both in their previous and current relationships. The young women were not only able to examine the relationships in their lives but they were also able to reflect on what traits they would like to have in a partner and healthy ways to communicate with others. One participant summed up the session by stating it “let me know what I want in life.”

Most of the participants reported enjoying and learning from sexual risk reduction activities, including those focused on learning how to assess a partner's risk and identifying fun and innovative ways to negotiate condom use. Despite the fact that the majority of participants were not newly diagnosed with HIV, many of the young women reported that they learned a lot and or liked the various sexual risk reduction activities. The majority of participants appreciated an activity that explored their sexual networks. Some participants stated they did not like the activity because it either “scared them” or it “showed too much” that they “didn't want to know.” The HIV disclosure activity was very well received by the young women, with almost half of the participants making a point to highlight the relevancy and usefulness of this activity in their lives.

Overall interventionists felt that the topics and activities were highly relevant and well received by the young women. They recommended that all topics covered in EVOLUTION be kept should the intervention be revised and disseminated. There were two broad topics regarding specific content areas included in the experimental intervention that interventionists highlighted: (a) relationships and (b) being positive.

According to the interventionists the most popular topic in the experimental intervention for young women was relationships. As one interventionist stated, “I remember that they really enjoyed talking about healthy and unhealthy relationships. That they really latched on to that and relationships are a huge issue for them both in terms of their family and with their partners as well as not really in the element of disclosure, but am I really going to find a relationship or a healthy relationship with HIV and so I would say that the relationships were really good and they liked the activities there.”

Another widely accepted topic was that of “being positive” and “what it means to be a woman with HIV.” As one interventionist stated “I think it was really important for them to talk about being positive with each other. Because they really don't do that outside of group and outside, maybe they do it on an individual basis, but not with other women that are experiencing it that are their own age.” Interventionists repeatedly reported that these sessions and activities were great examples of how important it is for young women living with HIV to talk about living with HIV, even when they might not be ready to acknowledge that they themselves struggle with these topics. As one interventionist recounted, “what it means to be a woman with and without HIV is an example of one of those activities that maybe they [the participants] did not feel comfortable with but I think it still sent home the message that like they did not want to acknowledge that they or people think differently about someone who does and does not have HIV. But it still brought up that issue for them to talk about and even if it was that they convince each other that it just didn't matter then that's helpful.” This session was seen as helpful by the interventionists as it looked at HIV from both a biological and social perspective and addressed topics such as self-esteem, stigma, and disclosure, and provided young women with sexual negotiation skills.

Some activities were less well received according to the interventionists. The interventionists reported that some participants enjoyed an activity called “sex degrees of separation” in which participants explore their sexual networks, yet some participants did not care for these sorts of activities as they did not feel comfortable with this new knowledge. Similarly, while the majority of young women enjoyed an activity called “love notes,” a team building activity where participants wrote notes to one another highlighting their strengths and assets, there were a few participants that did not want to express their feelings to other participants.

Areas in need of improvement

When participants were asked what they would change about the experimental intervention sessions and activities, the majority of participants responded “nothing” for each session. However there were three areas that participants mentioned should be addressed: (a) group dynamics, (b) session length, and (c) written assignments. While only mentioned a few times, the most common suggestion was to improve the ability of interventionists to adequately address counterproductive group dynamics. This recommendation was presented in the context of personality conflicts that arose in one of the groups, which resulted in friction and impediments to group cohesion and support. Another area of concern was the session length. While interventionists attempted to keep sessions to a maximum length of 3 h, there were a few sessions that ran over this time limit. The last area of concern was with the requirement of written assignments in the intervention. Since weekly sessions required minimal writing, this comment appeared to be focused on weekly homework assignments that assisted participants with applying the knowledge and skills learned from each week's session.

While the interventionists thought the format, structure, and content of EVOLUTION were good overall, there were a few recommendations if this intervention were to be implemented in clinical settings. Six areas in need of improvement included: (a) length of session, (b) content, (c) homework, (d) catering specifically to the age or needs of the individual group, (e) staffing constraints, and (f ) sustainability.

One challenge noted by the interventionists was the length of the sessions. While most sessions lasted between 2 and 3 h, there were quite a few that ran over 3 h. The interventionists all felt that keeping the session length closer to 2 h would be better, even if it meant increasing the number of sessions. As one interventionist stated, “If I were just to adapt this to like my practice I think what I would probably do is stretch it out over more weeks and just cover all the same stuff, just not do as much in one session. Right now, sessions groups together really nicely in terms of topics, maybe just, especially for my younger girls they just would always be looking at my thing and saying how much more do we have to go. So I just feel keeping them engaged by keeping them wanting more essentially by having more sessions rather than getting them to the point where they are really exhausted is the change I would make.”

Interventionists felt that the sessions overall “flowed,” but noted while there were some activities that participants were “really into it and got lost in,” there were other activities where participants were less enthusiastic and could be shortened. One topic and activity that interventionists felt could be improved upon was “combating and dealing with distorted thinking and changing your thinking” as they were “not sure the participants fully understood” the topic or the activity. One interventionist suggested approaching cognitive restructuring in a more simplified manner. Another topic and activity of suggested improvements was the session that included drugs and alcohol. While drugs and alcohol were thought to be useful and relevant topics, they felt that “there was not enough information presented to the participants” to make it meaningful. It was suggested that we include activities that “focus on changing habit or harm reduction.”

Each session asked for the participants to undertake some sort of homework where the participant would need to apply a skill learned in that week's session and then report back to group as to how the assignment went. While all the interventionists liked the idea of having the young women apply their new skills and “keeping the participants engaged throughout the week,” these homework assignments were met with resistance from the participants. One interventionist noted that “writing things down” was difficult for the participants and that “they would rather not write stuff down.” Another interventionist suggested that we “embed” the homework throughout the session and give specific scenarios for the young women to try out during the week, so that the young women can discuss how to apply these skills as they are being learned and are not tasked with creating an action plan to test out their new skills by themselves.

Another suggestion of the interventionists was to modify the sessions and activities so that they could cater specifically to the age or needs of the individual group. For example, if an interventionist found that she had a group of participants where drinking and drug use was the norm, the activities on alcohol and drug use could be more targeted and focus on harm reduction. In addition to being able to modify the sessions and activities based on the age and experience of the group, one interventionist suggested that instead of the intervention grouping 16- to 24-year olds together, it should either split young women into two age groups, 16- to 18- and 19- to 24-year-old, or divide young women based on whether they were still in high school. Opening the intervention to all young women regardless of HIV status was also recommend by one interventionist, as she felt the topics covered in EVOLUTION were relevant to both groups.

There were a few challenges noted regarding time and staffing. Preparation time for each session was noted as considerable by one of the interventionists. “Just because of the length of sessions, the prep time was more considerable than I expected it be, even though we had gone through the manual at the training and had done our practice sessions. Each session still required a lot of prep time which can be difficult when you have a 3 hour group in the day.” Another interventionist struggled with balancing her other job responsibilities at her site. One interventionist proposed the possibility of having a co-facilitator to decrease time and effort.

The topic of sustainability of this intervention in a real world clinic setting was also discussed as a possible challenge, as in the real world clinic settings there are not incentives and stipends available for participants as there are in a research setting. As one interventionist noted, “Even during the last session, I said hey guys this group as we know it is over but I am happy to host group if and us to continue and we can talk about different things at the clinic essentially and they all were like yeah yeah and I was like ok and I will call you and I called them about coming back and nothing ever happened. I can provide all the services, but I can't provide the incentives, the transportation, or food. You know I don't have any resources to do any of that and it would just be so good for them. And they say they want it. Of the 15 surveys I have handed out so far and 12 have said hey I want to come to group so they say they want it so that they can meet other people so they can talk about these issues but it's just making it happen is really difficult.”

Discussion

Adolescence can be a time of both turbulence and exploration. Adolescents, like adults, want to be loved and accepted, but due to their limited cognitive and behavioral skills, these desires may place them at risk for unfortunate consquences.22 However, young women's sexual development differs from young men as young women struggle with traditional gender norms, power imbalances, and dynamics that can place them in risky situations.22–25 As Marhefka and colleagues found, fear of stigma, rejection, and love among young women living with HIV, coupled with their limited sexual negation skills and the sexual power imbalances in their relationships, can provide a perfect scenario for unprotected sex and HIV transmission.22 Therefore, secondary prevention interventions must not only increase HIV transmission knowledge but address the specific emotional and psychological barriers young women face.22,25

EVOLUTION aimed to reduce secondary transmission by enhancing social and behavioral skills and risk reduction knowledge pertaining to young women's physical, social, emotional, and sexual well-being and addressing moderating factors that increase women's vulnerability. The process data presented here suggest that EVOLUTION is both an acceptable and feasible comprehensive secondary prevention intervention for YWLH. Participants welcomed the group setting, the structured content, and environment that EVOLUTION provided. They enjoyed the opportunity to engage with other young HIV-positive women like them, appreciated the personal commitment that the intervention required, and the opportunity to address important areas in their emotional, social, physical, and sexual health. They also appreciated the action-oriented aspects of the intervention where young women were actively engaged in creating positive changes in their lives, such as the participant contract, goal setting, and action plan calendar. This is in alignment with our empowerment framework where young women were encouraged to develop increased control over their current life circumstances, their future, and their overall quality of life.17–25 The young women enjoyed intervention components focused on improving self-perception and self-acceptance; coping and managing negative affect (e.g., stress, anger, depression); developing healthy romantic relationships (e.g., dating relationships, disclosure); and decreasing sexual risk.

They also appreciated the relevancy of the intervention's topics and the ability to apply their learned skills to their day-to-day lives. Retention throughout this nine session intervention remained high, illustrating that YWLH can be retained in a multi-session intervention.

While empowering YWLH with the skills and knowledge to address the moderating factors that impact their sense of control and power in their day-to-day life can increase the effectiveness of secondary prevention and improve their overall quality of life, a number of issues need to be considered before launching a full-scale trial of this intervention. Key among these are the challenges associated with group dynamics, literacy level of the potential participants, and site-specific barriers to implementing and engaging in such an intervention. Although the group format of the intervention was beneficial, developing a cohesive group was challenging at times. While group rules addressing the need to respect each group member and their beliefs were discussed at the beginning of the intervention and posted at each group session, providing interventionists with guidance and skills in conflict resolution when group rules fail to be upheld might be beneficial. The varying literacy levels of participants was also challenging since many participants had difficulty expressing themselves through writing and many intervention activities required participants to write down their responses. Developing alternative strategies through which participants can document their process of applying their new found knowledge and skills could also be helpful. While retention among young women who made it to the first group session was high, 20% of EVOLUTION's participants were lost to follow-up after first individual session. Therefore, interventions targeting YWLH really need to engage YWLH at the first session in order to retain them. Also, research on the barriers sites have in implementing multi-session behavioral interventions and the barriers young women might face in engaging and being retained in behavioral interventions should be taken into consideration. The level of detail available from the client satisfaction questionnaire limited the in-depth analysis of participants' assessment of the intervention and recommendations; therefore we would recommend that qualitative exit interviews or focus groups be conducted in future studies. EVOLUTION was a pilot study to explore the feasibility and acceptability of a secondary prevention intervention among young HIV positive women. Therefore, the sample size is small.

EVOLUTION is one of the first secondary HIV prevention interventions tailored specifically for young women living with HIV. Given the intervention's high acceptability ratings and ability to retain over 90% participants once they began the first group session, we are confident that, if found to be effective, this intervention would be acceptable among young women living with HIV and could be implemented by trained staff at clinical sites serving young women living with HIV.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: The Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions

Acknowledgments

The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) is funded by Grant Number U01 HD040533-06 from the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Bill Kappogianis, MD; Sonia Lee, PhD) with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (Nicolette Borek, PhD) and Mental Health (Susannah Allison, PhD). We would like to dedicate this article to Amanda and Lakeitsha, two of our Youth Advisory Team members, who passed away while this intervention was being piloted. Amanda and Lakeitsha not only spent hours with our team working to develop and shape this intervention, they shared their lives with us, and reminded us how important it is to empower young women. We would also like to thank Jaime Martinez, MD, PI, and Lisa Henry-Reid, MD Co- PI of the Adolescent Trials Unit at John Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, the staff of the Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center (Kelly Bojan and Rachel Jackson) and the Chicago site Interventionist, Vanessa Morrow; Ligia Peralta, MD, PI of the Adolescent Trials Unit, the staff at University of Maryland Medical Center (Reshma Gorle) and the Baltimore site Interventionist, Sara Clayton; Patricia Emmanuel, MD, PI of the Adolescent Trials Unit, the staff of the Tampa (Silvia E. Callejas) and the Tampa site Interventionist, Sabrinia Burns. ATN 089 has been scientifically reviewed by the ATN's Behavioral Leadership Group. We would also like to thank individuals from the ATN Data and Operations Center (Westat, Inc.) and Protocol Specialist Lauren Laimon; and individuals from the ATN Coordinating Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham including Craig Wilson, MD, Cindy Partlow and Marcia Berck. Finally, we would like to thank the young women who participated in this study for their willingness to share their time with us.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Vital Signs: HIV among Youth in the US. October2012. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2012/dpk-HIV-AIDS-Prevention.html Accessed July12, 2013

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Leading Causes of Death in Females: All Female- United States By Age Group. 2009http://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/2009/09_all_women.pdf Accessed July12, 2013

- 3.Hosek S, Brothers J, Lemos D, and the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions What HIV-positive young women want from behavioral interventions: A qualitative approach. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:291–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AmfAR Youth and HIV/AIDS in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities for Prevention Issue Brief. September2010. http://www.amfar.org/uploadedFiles/In_the_Community/Publications/Youth.pdf?n=5282 Accessed July12, 2013

- 5.Sturdevant MS, Belzer M, Weissman G, Riedman LB, Sarr M, Muenz LR. The relationship of unsafe sexual behavior and the characteristics of sexual partners of HIV infected and HIV uninfected adolescent females. J Adolesc Health 2001;29:64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Devanter N, Duncan A, Birnbaum J, Burrell-Piggott T, Siegel K. Gender power inequality and continued sexual risk behavior among racial/ethnic minority adolescent and young adult women living with HIV. J AIDS Clin Res 2011;25:003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Edu Behav 2000;27,539–565 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC HIV AIDS Fact Sheet: HIV/AIDS among Women. August2008. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/resources/factsheets/pdf/women.pdf Accessed July12, 2013

- 9.Fisher JD, Smith L. Secondary prevention of HIV infection: The current state of prevention for positives. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2009;4:279–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, et al. . A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: The WiLLOW Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;1:S58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel HML, Futterman D. Adolescents and HIV: Prevention and clinical care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2009;6:100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey SM, Bird ST, Galavotti C, Duncan EAW, Greenberg D. Relationship power, sexual decision making and condom use among women at risk for HIV/STDS. Women Health 2002;36:69–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, DeJong D, Gortmaker S, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care 2002;14:789–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Partner influences and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. Am J Commun Psychol 1998;26:29–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez CA, Marin BV. Gender, culture, and power: Barriers to HIV prevention strategies for women. J Sex Res 1996;33:355–362 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connell RW. Gender and Power. 1987, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher JD, Smith L. Secondary prevention of HIV infection: The current state of prevention for positives. Curr Opin HIV/AIDS 2009;4:279–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman M, Rappaport J. Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. Am J Commun Psychol 1988;16:725–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. Am J Commun Psychol 1995;23:581–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper G, Contreras R, Bangi A, Pedraza A. Collaborative process evaluation: Enhancing community relevance and cultural appropriateness in HIV prevention. J Prevent Intervent Commun 2003;26:53–71 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, and Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval Program Planning 1979;2:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marhefka S, Valentin C, Pinto R, Demetriou N, Wiznia A, and Mellins CA. “I feel like I'm carrying a weapon.’’ Information and motivations related to sexual risk among girls with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Care 2011;23:1321–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breakwell GM, Millward LJ. Sexual self-concept and sexual risk-taking. J Adolesc 1997;20: 29–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoveller JA, Johnson JL, Langile DB, and Mitchell T. Socio-cultural influences on young people's sexual development. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:473–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallerstein N. Evidence of Effectiveness of Empowerment Interventions to Reduce Health Disparities and Social Exclusion. 2006. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Health Evidence Network [Google Scholar]