Abstract

Significance: Autophagy is a fundamental cellular process that functions in the turnover of subcellular organelles and protein. Activation of autophagy may represent a cellular defense against oxidative stress, or related conditions that cause accumulation of damaged proteins or organelles. Selective forms of autophagy can maintain organelle populations or remove aggregated proteins. Autophagy can increase survival during nutrient deficiency and play a multifunctional role in host defense, by promoting pathogen clearance and modulating innate and adaptive immune responses. Recent Advances: Autophagy has been described as an inducible response to oxidative stress. Once believed to represent a random process, recent studies have defined selective mechanisms for cargo assimilation into autophagosomes. Such mechanisms may provide for protein aggregate detoxification and mitochondrial homeostasis during oxidative stress. Although long studied as a cellular phenomenon, recent advances implicate autophagy as a component of human diseases. Altered autophagy phenotypes have been observed in various human diseases, including lung diseases such as chronic obstructive lung disease, cystic fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Critical Issues: Although autophagy can represent a pro-survival process, in particular, during nutrient starvation, its role in disease pathogenesis may be multifunctional and complex. The relationship of autophagy to programmed cell death pathways is incompletely defined and varies with model system. Future Directions: Activation or inhibition of autophagy may be used to alter the progression of human diseases. Further resolution of the mechanisms by which autophagy impacts the initiation and progression of diseases may lead to the development of therapeutics specifically targeting this pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 474–494.

Introduction

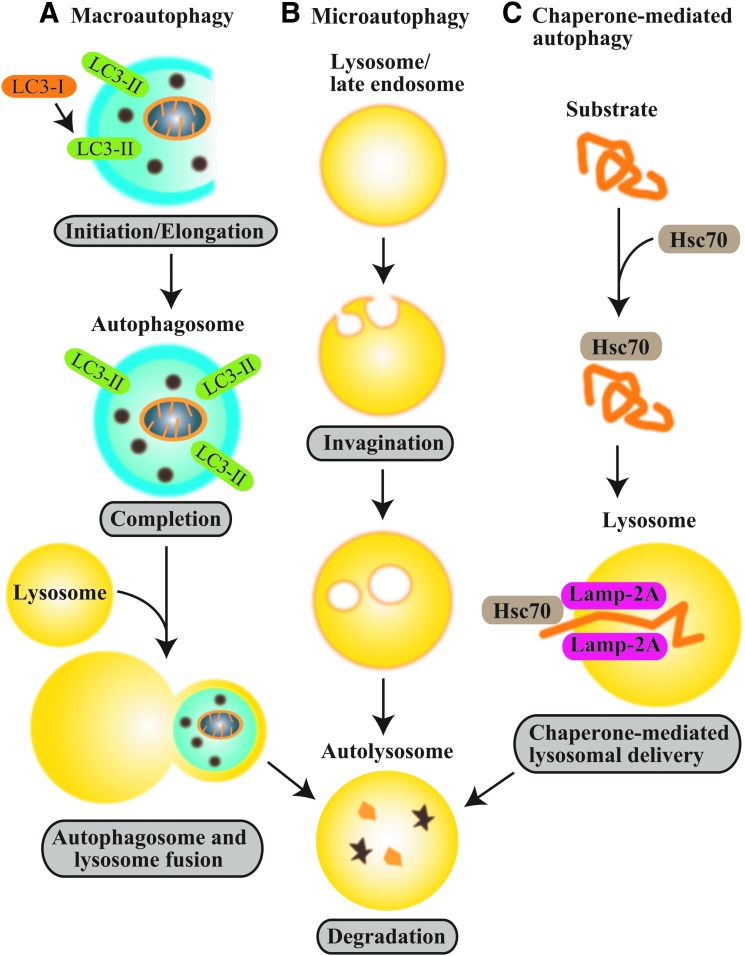

Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy, “self-eating”), a genetically programmed pathway for the turnover of cellular components, has emerged as a process crucial for cellular homeostasis (112). During autophagy, cytosolic substrates or “cargo” (e.g., proteins, lipids, and organelles) are assimilated in double-membrane vesicles, termed autophagosomes, and subsequently transferred to endosomes or lysosomes. Autophagic cargoes that are delivered to the lysosome are digested by lysosomal hydrolases to their basic components (i.e., amino acids and fatty acids), which are reutilized for anabolic pathways and energy production (112, 138). In addition to macroautophagy, two additional subtypes of autophagy (i.e., microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy) have been described (71, 148, 152) (see Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Autophagy subtypes. Autophagy has three major subtypes (A) macroautophagy, (B) microautophagy, and (C) chaperone-mediated autophagy. During macroautophagy, cytosolic substrates or “cargo” (e.g., proteins, lipids, and organelles) are assimilated in double-membrane vesicles termed autophagosomes, which contain the autophagy protein LC3-II (Atg8). Cargo-laden autophagosomes are subsequently fused to lysosomes. Autophagic cargoes that are delivered to the lysosome are digested by lysosomal hydrolases. In microautophagy, cytosolic components are directly assimilated into the lysosome or late endosomes by membrane invagination. In chaperone-mediated autophagy, proteins that contain a recognition sequence (KFERQ) are targeted to the lysosome by molecular chaperones (e.g., the 70 kDa heat shock cognate protein, Hsc70) in a process that requires the lysosomal receptor protein LAMP-2A. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Autophagy represents a physiological response to starvation, which prolongs cell survival by auto-catabolizing cellular macromolecules. This process replenishes pools of metabolic precursors in response to nutrient depletion (112). Autophagy exerts an important physiological function in protein turnover (85), and in organelle quality control, by disposing of dysfunctional or damaged organelles (e.g., mitochondria) (192).

Autophagy is highly inducible by environmental derangements, and it thereby constitutes an important part of the mammalian stress response (82). In particular, autophagy represents an inducible response to oxidative stress (5, 89, 144, 145, 154).

Recent studies have focused on understanding the functional roles of autophagy in specific human diseases, with respect to the contribution(s) of this process to disease prevention or pathogenesis (26, 94, 113, 138). Autophagy influences several physiological and pathophysiological processes that may impact disease outcome. These include the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis, as it relates to energy production and the execution of programmed cell death pathways (e.g., apoptosis) (48, 49, 157), and the regulation of innate or adaptive immune responses (36, 95). This review will discuss the fundamental relationships between autophagy and cellular homeostasis, and its regulation by pro-oxidant states. Further, the potential role(s) of autophagy in the pathogenesis of diseases that involve components of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation will be discussed, with an emphasis on pulmonary diseases.

Molecular Regulation of Autophagy

Mammalian autophagy responds to regulation by environmental signals through a network of proteins termed the core autophagic machinery. This regulatory system consists of autophagy-related gene (ATG) products that are homologues of similar proteins (Atg) originally identified in yeast (57). The core mechanisms for autophagy regulation have been previously reviewed elsewhere (138, 144, 145, 188).

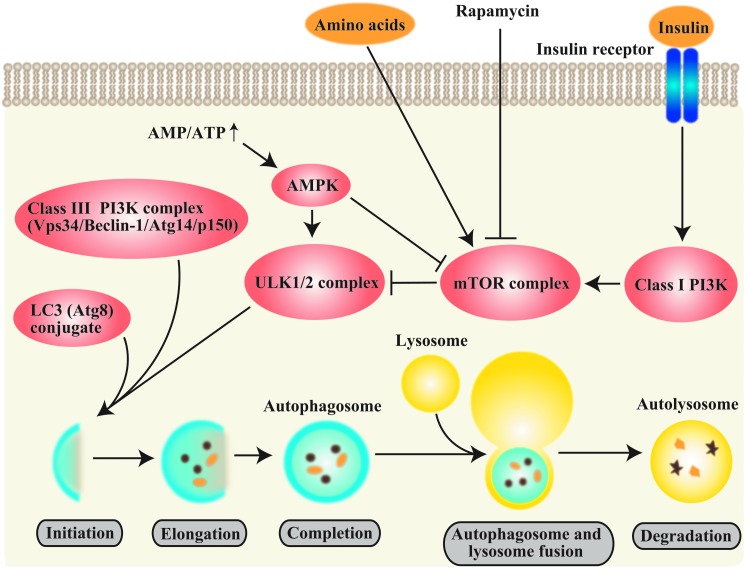

The autophagy pathway is negatively regulated by nutrient and growth factor-related signals and upregulated by starvation or energy depletion through the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. mTOR resides in a macromolecular complex (mTOR complex 1 [mTORC1]) that in turn negatively regulates the mammalian uncoordinated-51-like protein kinase (ULK1/2) complex responsible for activating autophagy (55, 60, 68, 69, 138) (Fig. 2). Autophagy is positively regulated by energy depletion by the 5′-adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which regulates mTORC1 (69, 77). Recent advances suggest that cytosolic deacetylases may also regulate autophagy during starvation. Activation of the NAD+-dependent deacetylase Sirtuin-1 results in the deacetylation of Atg5, Atg7, and Atg8, and activates Forkhead BoxO (FoxO) factors. Activation of FoxO has been associated with upregulation of Atg genes, increased autophagic activity, and mTOR inhibition (56).

FIG. 2.

Molecular regulation of autophagy. Autophagy responds to negative regulation by growth factor stimuli (e.g., insulin) that regulate the class I phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K/AKT) pathway, which upregulates the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. mTOR resides in a macromolecular complex (mTOR complex 1 [mTORC1]) This multiprotein complex is activated by nutrient-associated signals including amino acids and growth factors, and it negatively regulates autophagy by interacting with the ULK1 complex. Autophagy also responds to regulation by depletion of cellular energy charge through the increased activity of the 5’ adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK). In response to elevated AMP levels, AMPK inactivates mTORC1. The macrolide antibiotic rapamycin also stimulates autophagy by inactivating mTORC1. The initiation of autophagosome formation is also regulated by the autophagy protein Beclin 1 (Atg6). Beclin 1 associates with a macromolecular complex that includes hVps34, a class III phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3KC3), p150, and ATG14L. The basic sequence of steps of autophagy include (i) initiation and autophagosomal nucleation (formation of the phagophore), (ii) elongation of the nascent autophagosomal membrane, (iii) maturation of the double-membraned autophagosomal structure with cargo assimilation, and (iv) autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagosome elongation requires two ubiquitin (Ub)-like conjugation systems, the ATG5-12 conjugation system and the ATG8 (LC3) conjugation system. Autophagy protein LC3-II remains associated with the maturing autophagosome. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Autophagosome formation is also regulated by the autophagy protein Beclin 1 (mammalian homolog of yeast Atg6) (97,98). Beclin 1 associates with a macromolecular complex that activates autophagy, which includes hVps34, a class III phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3KC3), and other interactive factors (58, 188). Bcl-2 family proteins interact with Beclin 1 to inhibit autophagy (58, 131). The elongation and maturation of the autophagosome requires two ubiquitin (Ub)-like conjugation systems: the ATG5-ATG12 and the microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain-3 (LC3-ATG8) conjugation systems (138, 188). In mammals, the conversion of LC3-I (unconjugated cytosolic form) to LC3-II (autophagosomal membrane-associated phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form) is regarded as an indicator of autophagosome formation (114, 138).

Selective Autophagy

Until recently, autophagy was regarded as a nonspecific homeostatic cellular process, however, mounting evidence suggests that autophagy has a more selective role in the delivery of a wide range of specific cytoplasmic cargo to the lysosome for degradation (66). Selective autophagy processes are named after the specific cargoes sequestered into autophagosomes (e.g., “mitophagy” refers to the selective removal of mitochondria by autophagy) (66, 138).

Protein ubiquitination functions as a signal for selective autophagy in mammalian cells (64). Ub can be noncovalently conjugated as a monomer on one (mono-ubiquitination) or more (multi-ubiquitination) substrate lysine residues or as a polymer (poly-ubiquitination) by the sequential addition of further Ub moieties. Mono-ubiquitination regulates DNA repair, viral budding, and gene expression (147). Polyubiquitination through Ub Lysine-48 targets proteins for degradation by the proteosome, whereas Lysine 63-linked Ub chains regulate kinase activation, DNA damage tolerance, signal transduction, and endocytosis (147).

Ub-positive substrates, which are not cleared by the proteasome, recruit Ub-binding autophagic “receptors” to members of the LC3/GABARAP/Gate16 (Atg8) family on nascent autophagosomes. Although these receptors are known to act cooperatively and target both mono-ubiquitinated and poly-ubiquitinated substrates (78), their precise roles remain unclear. To date, several autophagy-specific adaptor proteins have been identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selective Autophagy Regulators and Cargo Adaptors

| Protein | Gene symbol | Regulation and function | Selective process | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p62/SQSTM1 | SQSTM1 | Ubiquitin-binding protein, cargo receptor for ubiquitinated targets | Aggrephagy | 27, 51, 64–66, 107, 122, 125 |

| Pexophagy | ||||

| Mitophagy | ||||

| Regulated by phosphorylation. | Xenophagy | |||

| Interacts with LC3 through LIR. | ||||

| NBR1 (neighbor of breast cancer, early onset-1, BRCA1 gene 1) | NBR1 | Ubiquitin-binding protein. Cargo receptor for ubiquitinated targets. Interacts with ALFY | Aggrephagy | 33, 79 |

| Pexophagy | ||||

| Xenophagy | ||||

| PINK1 (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted in chromosome 10)-induced kinase 1 | PINK1 | Ser/Thr Kinase. Recruits Parkin to depolarized mitochondria, upstream of p62 | Mitophagy | 51, 121, 179 |

| Parkin Parkinson protein-2 | PARK2 | E2 ubiquitin ligase. Ubiquitinates mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, upstream of p62 | Mitophagy | 21, 121, 153, 179 |

| Nix/Bnip3L | BNIP3L | Localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane and interacts with Atg8 mammalian homologs LC3/GABARAP through LIR. | Mitophagy | 38 |

| FUNDC1 | Localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane. Inducible by hypoxia. Interacts with LC3 through LIR. This interaction is regulated by dephosphorylation. | Mitophagy | 101 | |

| BNIP3 | Localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane. Inducible by hypoxia. Interacts with LC3/GATE16 through LIR. This interaction is regulated by phosphorylation. | Mitophagy | 195, 198 | |

| OPTN (optineurin) | OPTN | Interacts with Atg8 mammalian homologues LC3/GABARAP through LIR. This interaction is regulated by phosphorylation. | Xenophagy, Aggrephagy | 185 |

| SMURF1 (SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1) | SMURF1 | Participates in selective autophagy through membrane-dependent C2 domain. | Xenophagy, Mitophagy | 127 |

| NDP52 (nuclear dot protein 52 kDa) | NDP52 | Interacts with Atg8 mammalian homologues LC3/GABARAP through LIR. | Xenophagy | 19, 52,173 |

ALFY, 400 kDa, PI3P-binding autophagy-linked FYVE domain protein; BNIP3, Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein-3; LC3, microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3; LIR, LC3-interacting region; NBR1, neighbor of breast cancer-1, early onset [BRCA1] gene 1; NDP52, nuclear dot protein, 52-kDa; p62 (SQSTM1), sequestosome; 62 kDa autophagic cargo adaptor protein.

Aggrephagy

p62/sequestosome (p62/SQSTM1), an adaptor of selective autophagy, exerts an important function in the detection of cytoplasmic protein inclusion bodies, a hallmark of conformational diseases (proteopathies) such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's diseases, and various chronic liver disorders (64). p62 has an inherent ability to polymerize or aggregate and an ability to specifically recognize substrates (64). p62 participates in direct protein–protein interactions with ubiquitinated proteins via its ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain; and with LC3 localized to the isolation membrane via an LC3-interacting region (LIR) motif, thus facilitating the sequestration of ubiquitinated proteins in the nascent autophagosome (107, 112). In addition to p62, another selective autophagy adaptor neighbor of breast cancer-1, early onset [BRCA1] gene 1 [NBR1]) is required for the formation of Ub-positive protein aggregates, facilitating their sequestration and removal by the selective autophagic process known as aggrephagy (187). This process involves the 400 kDa, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P)-binding autophagy-linked FYVE (Fab-1, YGL023, Vps27, and EEA1) domain protein (ALFY), a scaffolding protein that directly interacts with p62 (27).

Mitophagy

Mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (mROS) (e.g., superoxide anion, O2−, and H2O2) are produced as byproducts of oxidative phosphorylation and may increase in response to toxins, or altered oxygen tension. If not removed by cellular antioxidant defenses, mROS can cause mitochondrial DNA and protein damage leading to mitochondrial dysfunction. As a result, mitophagy is required to perform quality control and remove damaged mitochondria. Mitochondrial turnover represents a housekeeping function of autophagy, whereas the accelerated turnover of mitochondria by mitophagy may result from distinct types of toxic interactions. Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm), and/or the increased production of mROS are believed to represent initiating signals for mitophagy (192).

Several autophagy receptors can signal the selective removal of mitochondria by autophagy (mitophagy). The mobilization of dysfunctional mitochondria to the autophagosome for turnover by mitophagy is initiated by the phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted in chromosome 10 (PTEN)-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) and Parkinson protein-2 (PARK2, Parkin) (51, 121, 192). Mutations in the corresponding PINK1 and PARK2 genes are associated with the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and recessive familial forms of Parkinson's disease (116, 175, 192).

PINK1, a transmembrane Ser/Thr kinase, is stabilized on damaged or depolarized mitochondria. Following loss of Ψm, Pink 1 recruits Parkin, an E3 Ub protein ligase, from the cytosol to the mitochondria (51, 121, 179), where it interacts with the GTPase mitofusin (21). Parkin initiates the formation of polyubiquitin chains that mark depolarized mitochondria for degradation. Parkin ubiquitinates many mitochondrial outer membrane proteins (porin, mitofusin, Miro, and others) (21, 153), that are subsequently recognized and targeted to autophagosomes by the autophagic cargo adaptor protein p62 (51, 192) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Pink1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy. Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential Ψm results in stabilization of Pink1, a Ser/Thr kinase, on the mitochondrial outer membrane. Pink1 recruits the Ub ligase Parkin to depolarizing mitochondria. Parkin then ubiquitinates mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, which serve as a target for selective cargo adaptors such as p62. In turn, p62 directs the targeting of ubiquitinated mitochondria to LC3-containing autophagosomes. Assimilation of mitochondria into autophagosomes leads to lysosome-dependent degradation through the autophagy pathway. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Genetic studies have confirmed the importance of autophagy in the maintenance of mitochondrial integrity. Loss of PINK1 function can promote oxidative stress and triggers mitochondrial fragmentation and autophagy (30), whereas overexpression leads to mitochondrial clustering and excessive accumulation of autophagosome-like structures (179).

While PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy represents a mechanism for the degradation of unhealthy mitochondria, alternative mitophagy pathways can regulate mitochondrial number to match metabolic demand. Mitochondria are removed in maturing erythrocytes by the BH3-only protein, Nix (Bnip3L). Nix localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane and directly interacts with mammalian Atg8 homologs LC3/GABARAP, through its LIR (38). Programmed removal of mitochondria by Nix in immature red blood cells (reticulocytes) allows these cells to live longer in the circulation due to reduced risk of damage induced by mROS (123).

Xenophagy

During infection, autophagy assists in immune responses by providing a mechanism for the selective intracellular degradation of invading pathogens, a process termed xenophagy (92). This function of autophagy can be manipulated by invading pathogens, and in some instances these pathogens can convert autophagic organelles into growth-supporting compartments (36). Invading bacteria are ubiquitinated and subsequently adaptors including p62, optineurin (OPTN) (185), Smurf1 (127), NBR1 (79), and nuclear dot protein, 52-kDa (NDP52) (173), can mediate their sequestration to autophagosomes (95).

ER-phagy, ribophagy, and RNautophagy

The relationship between the autophagy and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is complex, with the ER membrane representing a potential source of autophagosomal membrane (54), and substrate for autophagy. Fragments of ER containing unfolded proteins or aggregates may dissociate from the ER and be transported to autophagosome initiation sites, though the selective mechanism remains unknown (18). Since the discovery of autophagy, ribosomes have been observed inside autophagosomes in mammalian cells. The autophagic turnover of ribosomes (ribophagy) occurs with different kinetics than that of other cytoplasmic proteins and organelles (18). The specific cargo adaptors responsible for mammalian ribophagy remain unclear, as this process is well-characterized only in yeast (18). Additional evidence for ribophagy in higher eukaryotes arises from studies in Purkinje cells, where actively-translating polysomes are disassembled into non-translational monosomes and sequestered into autophagosomes (7).

RNautophagy, a process where RNA is taken up directly into lysosomes via LAMP2C, a lysosomal membrane protein, may also provide a mechanism by which autophagy regulates protein translation (47). Recent studies have also suggested a role for autophagy in microRNA regulation. Two major regulators of miRNA processing (i.e., DICER and AGO2) were found to be substrates of selective autophagy mediated by NDP52 (52).

Lipophagy and pexophagy

Lipids are stored in the cell in the form of lipid droplets (LD) that consist of cholesterol and triglycerides and function to supply free fatty acids needed to sustain mitochondrial β-oxidation and ATP levels (100). Chemical or genetic disruption of autophagy results in LD accumulation in hepatocytes. LC3 can be recruited to LD, suggesting that LD may be selectively removed by autophagy (a process termed lipophagy) (162). The mechanisms of LD sequestration into autophagosomes remain unclear, but they may involve the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) and LC3, which can associate with LDs in the absence of an autophagosomal membrane (100). Defects in lipophagy may result in altered mitochondrial β-oxidation, along with a failure to supply lipids for structural elements of the cell or to regulate lipid-dependent cell signaling (100). The adaptors p62 and NBR1 may act as autophagy-receptor proteins for pexophagy, the autophagic removal of peroxisomes, the organelles responsible for the breakdown of long chain fatty acids through mitochondrial β-oxidation (33, 125).

Autophagy in Inflammation and Innate Immunity

Autophagy and immunity

Autophagy has crucial roles in immune function and host defense against invading microorganisms. The autophagy machinery delivers microbes to the lysosome for degradation; and delivers microbial components (e.g., microbial nucleic acids or antigens) to toll-like receptors (TLRs) or antigen presentation molecules for further activation of immune responses (35, 83, 95). Further, autophagy proteins may control critical immune signaling pathways such as inflammasome or retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptor (RLR) signaling for cytokine production (34, 83, 95). Importantly, autophagy may be utilized as a self-defense mechanism for replication or survival of several intracellular microbes (83, 95). Thus, autophagy has diverse effects on immunity and in the pathogenesis of infectious or inflammatory diseases.

Role of autophagy in microbial clearance

Since the beclin 1 (Becn1) gene was shown to be protective against alphavirus encephalitis in 1998 (98), the protective role of autophagy in host defense has been extensively studied. Autophagy or autophagic protein exerts its role in host defense by degrading various clinically important pathogens in the lysosome. The target pathogens include bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (35), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (194), group A Streptococcus pyogens (119), Shigella flexneri (117), Salmonella enterica (19, 185), and Listeria monocytogenes (196), virus such as herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (191), and parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii (196).

Autophagy in microbial survival and replication

There is growing evidence that the autophagy machinery may also facilitate the replication of microbes in host cells. The pathogens exploiting the autophagic machinery for replication or survival include bacteria [e.g., Brucella abortus (166), Coxiella burnetii (53), Francisella tularensis (20)] and viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (84), hepatitis-B virus (HBV) (96, 174), hepatitis-C virus (HCV) (73), and Dengue virus (59, 73). Among these, autophagy has been shown to exert both killing (16, 17) and pro-survival (84), properties for some microbes such as HIV. Recent studies support a pro-survival role of autophagy on HBV (174), and coxsackie virus in vivo (2).

Autophagy proteins and innate immune signaling

In addition to direct effects on pathogen clearance, autophagy may have an impact on invading microorganisms by activating immune signaling pathways and releasing immunological mediators such as cytokines. These mediators promote activation of innate immune systems including inflammation, phagocytosis, and by further promoting autophagic activity for digesting microbes (83, 95). Diverse effects of autophagy on innate immune signaling have been reported (35, 83, 95). The autophagy pathway promotes TLR7-mediated production of interferon-α (IFN-α), a potent anti-viral mediator, in response to single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus such as vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and in chimera-mice (87). In contrast, deficiency of ATG5 enhanced IFN-α production in response to VSV mediated by upregulating RLR signaling in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (170). Atg5-Atg12 conjugates negatively regulate type I IFN production in MEFs by direct association with RIG-I and IFN-β promoter stimulator (IPS-1), critical molecules for RLR signaling, through caspase recruitment domains (67). This differential observation might be due to differential signaling pathways between pDCs and other cell types such as MEFs. pDCs recognize ssRNA virus by TLR7 and TLR8 in endosomes, whereas most other cells use RIG-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) to sense viral replication in the cytosol (45, 70, 189). The type I IFN signaling is also regulated by other autophagic proteins (e.g., Atg9a) in response to double-stranded DNA stimulation (149). The antiviral activity of IFN-γ against murine norovirus requires several autophagy proteins such as Atg5-12, 7, and 16, but it does not require induction of autophagy (62). Complex formation of autophagy proteins including ATG5-12/ATG16L1 can exert a nondegradative role in IFN-γ-mediated antiviral defenses (62).

The role of ATG16L1 in inflammation has been initially linked to Crohn's disease. A genome-wide association study reveals that atg16L1 is one of the critical susceptibility genes (140). Subsequently, Atg16L1 has been shown to be critical to regulate interleukin (IL)-1β secretion but not gene expression. IL-1β secretion in response to lipopolysaccharide was enhanced by knockdown of atg16L1 and atg7 in macrophages (150). Pharmacological inhibition of autophagy using 3-methyladenine (3-MA) also enhanced IL-1β secretion (150). Secretion of IL-1β in immune cells is tightly regulated by caspase-1 (32, 137).

Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes responsible for the activation of caspase-1 and downstream immune functions. Inflammasome activation is exclusively responsible for caspase-1-mediated IL-1β and IL-18 maturation and secretion in immune cells (32, 137). Recent reports demonstrate mitochondrial homeostasis as a key mechanism that regulates inflammasome activation (120, 197). Depletion of autophagy proteins such as Beclin 1, LC3B, and ATG5 augments mitochondrial dysfunction including mitochondrial membrane depolarization, enhancement of mROS generation, and mitochondrial DNA release into cytosol, resulting in increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 (120, 197). In addition, AMPK, a critical upstream molecule for autophagy induction that regulates ULK1 complex, also negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating mROS generation (183). Thus, autophagy proteins negatively regulate inflammasome activation by regulating mitochondrial function. Another mechanism by which autophagy regulates the inflammasome is through ubiquitination (158). Inflammasome signals trigger G protein RalB-mediated autophagy (158). Assembled inflammasome complexes undergo ubiquitination and recruit the autophagic adaptor p62, which assists in their delivery to autophagosomes (158). In contrast to this negative regulation of autophagy by the inflammasome, a recent study shows that autophagy induction by starvation enhances caspase-1 activation and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 (42). Inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion utilizes the autophagy-based unconventional secretion pathway (42). It is possible that a distinct type of autophagy induction might differentially regulate the inflammasome pathway.

Autophagy and adaptive immunity

The roles of autophagy in adaptive immunity include antigen presentation and antibody production (190). There are antigen recognition molecules by which macrophages or DCs capture foreign antigens and enable T cells to recognize them: Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II. Autophagy induced during HSV-1 infection enhances the endogenous antigen presentation on MHC class I molecules and activates CD8+ T cells (43). Autophagy is also required for presenting antigen on MHC class II molecules and activation CD4+ T cells (88, 128). Mice with DC-conditional deletion of atg5 fail to produce IFN-γ and were more susceptible to HSV-2 infection (88).

Autophagy is also required for B cell differentiation (28), and maintaining the number of B-1 B cells that is a subset of B cells, but not B-2 B cells (110). Atg5−/− progenitors exhibit a defect in B cell development at the pro- to pre- B cell transition (110). Autophagy has been shown to be induced by anti-IgM Ab stimulation in B cells (182). Recent studies suggest that plasma cells require autophagy for sustainable antibody production (132). These results taken together suggest that autophagy is involved in adaptive immune function.

Autophagy in Oxidative Cellular Stress

Accumulating evidence using pro-oxidant compounds has suggested that autophagy represents a general inducible response to oxidative stress (22, 144, 145, 154, 181). Additionally, autophagy can be modulated during altered states of oxygen tension, including hyperoxia, and hypoxia, corresponding to increased or decreased pO2, respectively (91, 171). Autophagy may be regarded as a secondary defense to oxidative stress, by virtue of its ability to facilitate the turnover of damaged or modified substrates, such as protein, which may accumulate during this condition. Since mitochondria represent both a primary source of ROS and a functional target for ROS generation, the function of autophagy in mitochondria quality control may play a central role in the oxidative stress response. Further, recent studies indicate possible cross-regulation of autophagy with the mammalian antioxidant response. Recent evidence suggests that certain autophagy-related proteins may be subject to direct redox regulation (e.g., ATG4B) (154) or transcriptional regulation by oxidative stress (e.g., p62) (65).

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), when used as a model compound for oxidative stress, can induce a caspase-independent cell death in transformed or cancer cell lines, which is accompanied by morphological features of autophagy. These effects of exogenous H2O2 on autophagy could be inhibited by synthetic antioxidants (22). Autophagy can also be upregulated by ROS generated from redox-cycling compounds, such as menadione (2-methylnaphthalene-1,4-dione), which produce intracellular H2O2 and O2− by electron transfer reactions in the mitochondria (181). In addition to macroautophagy, recent studies suggest that chaperone-mediated autophagy can be induced by menadione and may assist in the processing of oxidatively-modified proteins (72).

On the basis of genetic knockdown experiments and inhibitor studies, autophagy has been implicated as a mechanism for resistance to oxidative stress, but also as a mechanism for sensitization depending on cell type, inducing agent, and model system. For example, inhibition of the autophagic pathway using 3-MA, a class I PI3K inhibitor, or genetic interference of core autophagic proteins Beclin 1, Atg5, and Atg7 prevented cell death induced by H2O2 in cancer cells (22). Further, Atg5−/− MEFs were resistant to H2O2-induced cell death, through upregulation of the ERK1/2 pathway (135).

In contrast, genetic knockdown of Atg5 was shown to sensitize hepatocytes to cell killing following exposure to menadione, associated with ATP depletion and activation of the c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway (181), whereas Atg5−/− embryo fibroblasts resisted menadione-induced apoptosis (161, 180). The explanation for variable results observed between experimental models is not entirely clear but may include cell-type and inducer-specific effects, dose-dependent effects, off-target activities of autophagy proteins and inhibitor compounds, and differential availability of compensatory mechanisms.

Endogenously produced ROS have also been implicated as signaling mediators in the induction of autophagy by diverse stimuli, including nutrient depletion and pro-inflammatory mediators. For example, starvation-induced autophagy requires endogenous mROS production (154). In established cell lines, serum starvation caused an increase in mROS production that occurred downstream of PI3KC3 activation, since it was downregulated by 3-MA. Treatment of cultured cells with the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine inhibited autophagosome accumulation during starvation (154). Autophagy triggered by glucose depletion or serum starvation could be inhibited by exogenous catalase or overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase (154). Further, mROS have also been proposed as signaling intermediates in the stimulation of autophagy by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) (9, 39). Taken together, these findings suggested an important signaling role for mROS in the regulation of autophagy.

Autophagy and the antioxidant response

Recent studies suggest cross-regulation of autophagy by the cellular antioxidant response. The oxidative stress response transcription factor, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) is a master regulator of cellular antioxidant defenses. Nrf2 dissociates from its cytoplasmic inhibitor Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 (Keap-1) and binds to antioxidant response elements in promoters of genes critical for adaptation to oxidative stress (65, 136).

The autophagic cargo adaptor protein p62, which is activated in response to a number of stress response pathways including nutrient deprivation, mitochondrial damage, and oxidative stress, is a newly-identified target gene of Nrf2 (65). p62 interacts and competes with Keap-1 at the Nrf2 binding site, promoting Nrf2 release from Keap-1 maintaining antioxidant gene expression (80, 122). Keap-1 is also constitutively degraded by p62-dependent autophagy, such that Nrf2 accumulates in the liver of autophagy-deficient mice (169). Sestrins (Sesns), proteins involved in protecting cells from oxidative stress also promote p62-dependent autophagic degradation of Keap-1 and prevent oxidative liver damage (6).

Oxygen regulation of autophagy

Hyperoxia (elevated pO2) causes oxidative stress through the increased production of ROS from cytosolic (i.e., NADPH oxidases) and mitochondrial sources (129). In vivo, epithelial cell death is believed to play a critical role in hyperoxia-induced lung injury (29). Prolonged hyperoxia (>95% O2), which causes characteristic lung injury in mice (29) caused activation of morphological and biochemical markers of autophagy in vivo (171). In vitro, hyperoxia exposure induced the expression and conversion of LC3B-I to LC3B-II in cultured epithelial cells (Beas-2B and human bronchial epithelial cells) and increased autophagosome formation. The increased LC3B expression during hyperoxia was regulated at a transcriptional level and required the activation of the JNK signaling pathway. LC3B knockdown by siRNA increased hyperoxia-induced cell death in epithelial cells, whereas overexpression of LC3B conferred cytoprotection after hyperoxia. These findings suggested a protective role for autophagic protein LC3B during hyperoxia-induced cellular injury. The activation of LC3B by hyperoxia was inhibited by the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine, and by mito-TEMPO, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (171). LC3B was also shown to play a critical role in hyperoxia-induced epithelial cell apoptosis. Genetic interference of LC3B promoted death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) formation, a regulator of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, and hyperoxia-induced cell death in epithelial cells. Conversely, overexpression of LC3B conferred cytoprotection after hyperoxia, by inhibiting DISC formation, the cleavage of caspase-3 and initiation of apoptosis. An intermolecular interaction between LC3B and Fas was described, which required the caveolae scaffolding protein caveolin-1. These experiments suggested that LC3B acts as a pro-survival factor in oxygen-dependent cytotoxicity, and that the mechanisms regulating autophagy and apoptosis may share common features during oxygen toxicity (171).

Autophagy in hypoxia

Hypoxia, or reduced pO2, can result in impaired mitochondrial electron transport chain activity, increased mitochondrial O2− production, and mitochondrial dysfunction. The hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), a major regulator of the hypoxic response in mammals, has recently been implicated in the regulation of hypoxia-induced autophagy (195). HIF-1α deleted MEFs displayed inhibition of hypoxia-regulated autophagy. These studies identified an HIF-1 target gene, Bcl-2 family member Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein-3 (BNIP3), and a BH3-containing protein, in the hypoxic regulation of autophagy (195). BNIP3 activates autophagy through the displacement of inhibitory Bcl-2 family proteins (i.e., Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL) from their complexes with Beclin 1 (195). Hypoxia also induced FUNDC1, independently of apoptosis signaling. FUNDC1 acts as a receptor for hypoxia-inducible mitophagy, which interacts with LC3 through its LIR domain (101).

We have shown that autophagy can be induced in primary human lung vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells subjected to acute hypoxia exposure. In vascular cells, hypoxia induced the expression of Beclin 1, the conversion of LC3B-I to LC3B-II, and increased autophagosome formation (91). These observations were consistent with increased autophagic flux during hypoxia, as determined by increased LC3B-II levels with the addition of bafilomycin-A1. Similar findings were described after exposure to chronic hypoxia in vivo, with mouse lungs displaying increased LC3B-II formation, and increased autophagosome formation (91). Genetic interference of LC3B using siRNA increased the proliferation of endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vitro and also inhibited smooth muscle cell apoptosis in response to pro-apoptotic agents (91). In contrast to these findings, inhibition of AMPK, an activator of autophagy, increased smooth muscle cell apoptosis in the hypoxia model (63).

Genetic interference of LC3B in endothelial cells increased intracellular ROS production, and it also stabilized HIF-1α. Conversely, overexpression of LC3B in vascular cells supressed mitogen and hypoxia-dependent proliferative responses in cultured vascular cells (91). Becn1+/– endothelial cells also displayed enhanced proliferation in vitro in response to hypoxia relative to wild-type cells (90). These studies described a function of LC3B in regulating vascular cell responses to hypoxia, though the possibility that LC3B affects signaling pathways independent of autophagic regulation could not be excluded (91).

Autophagy and the ER stress response

The ER performs important cellular functions including the post-translational processing, folding, and trafficking of newly synthesized proteins, and the regulation of the intracellular calcium flux. A number of xenobiotics and environmental derangements (e.g., hypoxia, calcium ionophores, oxidative stress, and inhibitors of protein glycosylation) can disturb the normal function of this organelle, causing ER stress associated with the accumulation of malfolded protein aggregates (8, 155). The unfolded protein response (UPR) occurs as an adaptive compensatory reaction to ER stress charaterized by the upregulated synthesis of ER chaperone proteins (i. e., 78-kDa glucose regulated protein, GRP78), the attenuation of protein translation, and the activation of an ER-associated protein degradation system (155). The UPR is regulated by several molecules including inositol requiring kinase 1 (IRE1), activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6), and protein kinase R–like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) (155). ER stress may also lead to apoptotic cell death, through activation of specific caspases (i.e., caspase-12, -9, -8), and the transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) (168). The relationship between ER stress and the activation of autophagy has been demonstrated in several cell types. For example, lung fibroblasts subjected to ER stress-inducing chemicals (e.g., thapsigargin) displayed increased accumulation of LC3-II, in parallel with activation of the UPR (124). Activation of autophagy by chemical-inducers of the ER stress response promoted cell survival in transformed cell lines, but promoted cell death in the corresponding untransformed lines (37). Induction of autophagy with ER stress-inducing agents promoted cell death in apoptosis-deficient Bax−/−Bak−/− fibroblasts but inhibited cell death in normal fibroblasts (176). Hypoxia can also trigger the UPR by upregulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β, which leads to the induction of PERK signaling (3). Activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) is a transcription factor induced under severe hypoxia and a component of the PERK pathway involved in the UPR. ATF4 is required for ER stress and hypoxia-induced expansion of autophagy by directly binding to a cyclic AMP response element binding site in the LC3B promoter, resulting in LC3B upregulation (146). Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins negatively regulate autophagy by binding Beclin 1 in the ER, an interaction competed for by Ambra-1, and by downregulating ER Ca2+ accumulation associated with autophagy induction (61, 167). Further, the interaction of the inositol triphosphate receptor (IP3R) with Bcl-2 at the ER membrane regulates the availability of Bcl-2 to inhibit autophagy (61, 141).

Taken together, autophagic activation during ER stress may represent an overflow pathway for the degradation of a toxic accumulation of aggregated protein. Additional studies will be required to define the relationship between the ER pathway and autophagy in the context of disease models.

Autophagy at the Doorstep of Cell Death

Autophagy is a regulated program associated with survival or stress adaptation. However, increased autophagosome formation is often coincident in cells that are dying. Thus, autophagy could represent a failed adaptive mechanism that may have prevented death under milder conditions. Alternatively, excess activation of autophagy may contribute to cell death through unchecked degradative processes, however, the precise contribution of autophagy to cell death remains unclear (49, 157). The terms “autophagic cell death” or type II programmed cell death have been used to refer to cell death distinct from apoptosis that occurs in association with increases in autophagosome formation, and independently of caspases (157). In contrast, apoptosis (type I programmed cell death) refers to a regulated form of cell death that requires proteases (e.g., caspases) and nucleases for cell death without loss of membrane integrity (48). The major features of apoptosis include nuclear degradation with chromosomal DNA fragmentation, cell surface blebbing, cell shrinkage, and mitochondrial dysfunction (48). Autophagy and apoptosis remain incompletely delineated, as the two processes are not always mutually exclusive and can simultaneously occur in the same cell (49, 157). Suppression of autophagy by Beclin 1 or LC3 knockdown, or by chemical inhibitors such as 3-MA, can promote apoptosis and caspase-3 activation in starved HeLa cells. These studies suggest a role for autophagy as a means for prolonging cell survival, particularly during starvation (15). In contrast, knockdown of autophagic proteins has been shown to prevent cell death in certain toxicological models, as discussed later in this review (23, 24, 76).

The signaling pathways that regulate autophagy and those that regulate apoptosis share some potential for cross-regulation (49, 157). Several proteins that regulate the core autophagic machinery can interact with apoptosis-regulatory pathways. For example, Beclin 1 forms a complex with Bcl-2 family members including Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL (98, 131). Binding of Bcl-2 family proteins to Beclin 1 inhibits autophagy by preventing the association of Beclin 1 with the PI3KC3 complex. Conversely, Beclin 1 may be cleaved by caspases during activation of apoptosis (104). The autophagic protein Atg5 may affect extrinsic apoptosis pathways through interactions with the Fas-associated death domain (FADD) protein (134). Atg5 promotes apoptosis, through a calpain-dependent truncation product, which binds to and inhibits Bcl-XL (193). Atg4B, a critical effector of LC3B processing, has been identified as a substrate for pro-apoptotic caspase-3 (12). The autophagic protein Atg3 has recently been identified as a caspase-8 substrate, which is cleaved during TNFα-induced apoptosis (126).

Several regulators of apoptosis pathways such as p53 can regulate autophagy (93). For example, p53 targets the expression of damage-regulated autophagic modulator, which stimulates autophagy. Conversely, the cytoplasmic form of p53 may act as an inhibitor of autophagy (93). BNIP3 is a BH3-only protein that can trigger apoptosis by sequestering anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and promoting Bax/Bad-dependent mitochondrial release of pro-apoptotic mediators. BNIP3 also stimulates mitophagy by disrupting the interaction between Bcl-2 and Beclin 1 (198).

Autophagy may provide an alternative pathway to cell death in apoptosis-deficient cells. For example, in Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs, which cannot activate intrinsic apoptosis, treatment with chemotherapeutic agents results in non-apoptotic necrosis-like cell death accompanied by excessive autophagosome formation (159). Additional studies are needed to define the dynamic equilibrium between autophagy, apoptosis, and necrosis in the context of human disease pathogenesis (157).

Role of Autophagy in Pulmonary Disorders

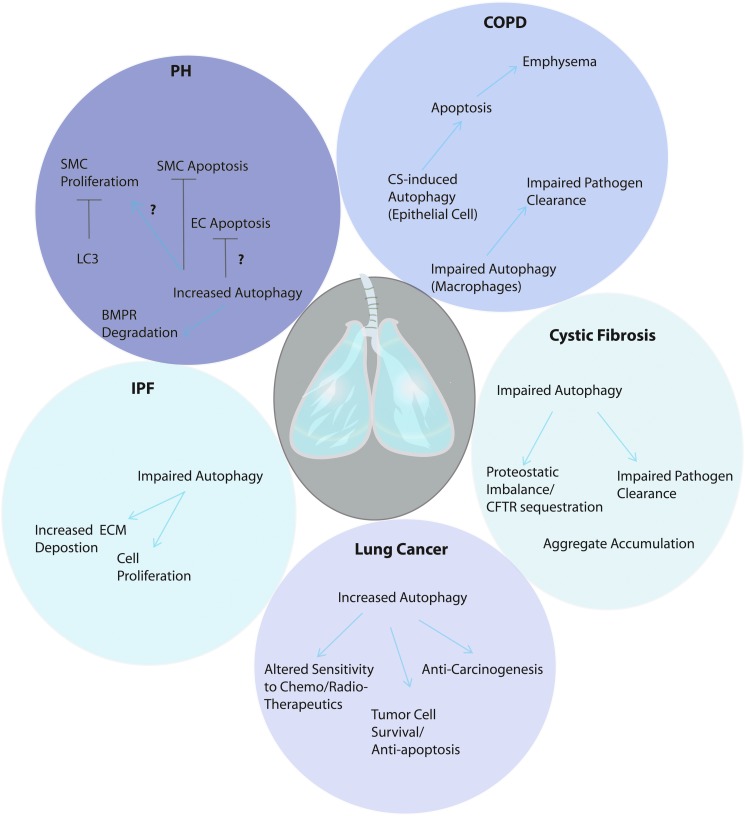

Autophagy may play multivariate and context-specific roles in human disease. This is exemplified by protagonist and antagonist roles observed in recent studies using models of pulmonary disease (Fig. 4), as outlined in the following sections.

FIG. 4.

Role of autophagy in pulmonary diseases. Autophagy can play a complex role in pulmonary diseases as discussed in this review. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, autophagy may play a pro-pathogenic role by amplifying apoptotic responses of epithelial cells to cigarette smoke exposure. However, a possible role of impaired macrophage-dependent autophagy of pathogens may also play a contributory role to disease process. In pulmonary hypertension (PH), recent studies suggest that autophagic proteins may modulate both proliferative and apoptotic responses of vascular cells that may play contributory roles to the development of PH. Autophagy has also been implicated in the degradation of bone morphogenetic protein receptor (BMPR), implicated in PH pathogenesis. Whether autophagy ultimately represents a protective or harmful mediator in this disease remains under study. In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) impaired autophagy may promote disease pathogenesis, through enhanced fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Recent studies also suggest that cystic fibrosis is a disease of impaired aggrephagy, which results in accumulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) inclusions and altered proteostasis. A role for autophagic deficiency in impaired pathogen clearance may also be important in this disease. Autophagy plays variable roles in lung cancer, by inhibiting carcinogenesis and genetic destabilization, and also promoting the survival of tumor cells. Autophagy also has been shown to influence the sentisitivity of cancer cells to therapeutics. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Autophagy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a pulmonary disorder characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible and by pathologic changes in the proximal and peripheral airways, lung parenchyma, and pulmonary vasculature (178). Cigarette smoke (CS) is the most common identifiable risk factor for COPD with smokers having a greater COPD mortality rate than nonsmokers (178). CS is a complex mixture of over 4700 components including heavy metals, aldehydes, aromatic hydrocarbons, phenolics, and oxidants (23).

We have observed dramatic increases of autophagy proteins in lung tissue derived from COPD patients at various stages of disease severity (23). The expression level of LC3B-II, a marker of autophagosome formation, and the expression of additional autophagy-associated proteins Atg4, Atg5-Atg12, and Atg7, were increased in COPD lung relative to control lung (23). Electron microscopic analysis of lung tissue from COPD patients revealed enhanced production of autophagosome formation in COPD lung compared to control tissues (23). We have also observed increased expression of autophagy proteins in the lungs of C57Bl/6 mice exposed to environmental CS for 12 weeks. CS-exposed mouse lung displayed increased autophagosome formation by electron microscopic analysis and increases in LC3B-II (23).

Additionally, increased autophagy was also observed in the genetic variant of emphysema, α1 anti-trypsin deficiency (α1-AT), whose etiology is independent of smoke or particle inhalation. These observations suggest that intrinsic factors, such as increased matrix proteolysis or inflammation may contribute to the activation of autophagy in COPD, in addition to direct cellular responses to CS (23). In contrast, increased markers of autophagy were not observed in lung tissue with other lung diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis, and systemic sclerosis (23). These observations suggest that autophagic protein expression and autophagosome formation could serve as tissue biomarkers of certain pulmonary diseases.

We have also identified a functional role for autophagic proteins in CS-induced epithelial cell death (23, 24). In vitro studies with cultured epithelial cells subjected to aqueous cigarette smoke extract (CSE) exposure responded with increased autophagosome formation. CSE induced the increased processing of LC3B-I to LC3B-II in epithelial cells. LC3-II levels were further increased by bafilomcyin A1 and protease inhibitors, indicative of autophagic flux (24, 76), and inhibited by antioxidants such as N-acetyl-L-cysteine (76). CSE concurrently induced extrinsic apoptosis in epithelial cells involving early activation of DISC formation and downstream activation of caspases (-8, -9, -3). Knockdown of autophagy proteins Beclin 1 or LC3B inhibited apoptosis in response to CSE exposure in vitro, suggesting that increased autophagy occurred in association with epithelial cell death, and that autophagic proteins may be directly involved in cell death regulation in the CSE exposure model (23, 24, 76).

Further studies revealed that LC3B may regulate extrinsic apoptosis in the CSE exposure model (24). LC3B was found to engage a complex with Fas, a component of the DISC, in a fashion dependent on the caveolae-scaffolding protein caveolin-1. CSE exposure caused the rapid dissociation of LC3B from complex with Fas, consistent with activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. The pro-apoptotic effect of LC3B expression was impaired by mutation of the caveolin-1 binding motif of LC3B (24).

Genetic deletion of the autophagic protein LC3B inhibited CS-induced emphysematous airspace enlargement in vivo (24). In contrast, caveolin-1-deficient cells and Cav-1−/− mice were found to exhibit higher levels of autophagy and apoptosis in response to CS exposure in vitro and in vivo, respectively. Consistently, Cav-1−/− mice were found to be sensitized to CS-induced airspace enlargement in an in vivo model of CS-induced emphysema (24).

The mechanisms underlying the transcriptional regulation of LC3B were also examined in the CSE exposure model. The LCB promoter contains consensus binding sites for the transcription factor early growth response-1 (Egr-1). Egr-1 is the product of an immediate early response gene that is induced rapidly following cellular stress in vitro, and which can regulate apoptotic and inflammatory signaling cascades. Egr-1 binding to the LC3B promoter increased in response to stimulation by CSE in epithelial cells. Knockdown of Egr-1 inhibited the activation of LC3B in response to CS exposure in epithelial cells (23). Interestingly, Egr-1−/− mice were resistant to the pro-apoptotic and pro-autophagy effects of chronic CS exposure in vivo, and to CS-induced airspace enlargement. However, Egr-1−/− mice also exhibited significant basal airspace enlargement, indicating a potential role for Egr-1 in lung development (23).

These data, taken together, suggest that the stimulation of the autophagy pathway may promote cell death during CS exposure, and data also implicate autophagy-dependent epithelial cell death as a possible contributing factor to emphysematous airspace enlargement (23, 24). However, it remains unclear whether autophagic flux directly contributes to the alveolar epithelial cell death in COPD or whether these effects are due to signaling properties of autophagy proteins independent of their role in autophagy.

A recent study has analyzed autophagy in alveolar macrophages isolated from the lungs of active smokers (115). In this study, activation of autophagic markers, including LC3-II and autophagosome formation, were observed in smoker's macrophages. The macrophages also displayed elevated autophagosome formation by ultrastructural analysis. On the basis of chemical inhibitor studies using chloroquine, the authors concluded that autophagic activity was impaired in alveolar macrophages from smoker's lungs (115).

Until recently, the role of autophagy in COPD has focused on the role of classical nonselective autophagy; however, emerging data suggest that selective autophagy may play an important role in this disease. Increased accumulations of p62 and Ub-modified proteins were detected in lung homogenates from COPD patients and in human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to CSE (46). CS exposure may impair the delivery of bacteria to lysosomes (115), suggesting that defective xenophagy in alveolar macrophages of smokers may contribute to recurrent infections in COPD patients. CS affects oxidative protein folding in the ER (74), and it can induce the UPR in human alveolar epithelial cells (165), which may lead to ER stress and impaired protein homeostasis in the lungs of COPD patients (13, 105, 111).

Previous studies show that muscle mitochondrial function is altered in patients with COPD (31, 118, 133, 164), and that CS induces rapid depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential in human pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells with loss of cellular ATP (163, 177). As a damage control mechanism, mitophagy may be activated in response to CS exposure. Further studies are required to investigate the role of mitophagy in the pathogenesis of COPD.

In conclusion, autophagy modulation can be observed in lung macrophages, bronchial and epithelial cells upon CS exposure (23, 24, 115), and in the lungs of COPD patients. Further studies will be needed to determine the relationships between autophagic flux, cell death, and emphysema development. Additionally, the impact of autophagy on inflammatory processes in COPD cannot be excluded. Selective autophagy processes (e.g., mitophagy) may also play contributory and heretofore poorly-characterized roles in this disease, and this also warrants further investigation. Therapeutic strategies in treating COPD may involve agents that target autophagy proteins and/or modulate selective autophagic clearance and turnover.

Autophagy in cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a fatal autosomal recessive disease, which is caused by mutation in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). CF is characterized by abnormally viscous mucous, which obstructs organ passages, resulting in recurrent pulmonary infections. The most common CFTR mutation is a deletion of phenylalanine at position 508 (CFTRF508del) in the CFTR gene (142). Cells with CFTRF508del display accumulated polyubiquitinated proteins, defective autophagy and the decreased clearance of aggresomes (11). Dysfunctional autophagosome clearance in CF has also been shown to contribute to heightened inflammatory responses implicating autophagy and AMPK-AKT signaling pathways as novel anti-inflammatory targets in CF (108). Defective CFTR also results in increased ROS production and upregulation of tissue transglutaminase (TG2), an important factor of the inflammatory response in CF (103). TG2 results in the cross-linking and inactivation of Beclin 1, leading to sequestration of PI3KC3 and accumulation of p62 (103). Restoring Beclin 1 or deletion of p62 rescued the trafficking of CFTR (F508del) to the cell surface. These data suggest that selective autophagic processes such as aggrephagy or mitophagy, may contribute to pathogenesis of CF.

Xenophagy may also be impaired in CF. Administration of the autophagy-stimulating agent rapamycin decreases Burkholderia cenocepacia infection and reduces inflammation in the lungs of CF mice (1). Azithromycin, a potent macrolide antibiotic used in patients with CF is associated with increased infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Interestingly, azithromycin has been shown to block autophagosome clearance by preventing lysosomal acidification, impairing autophagic and phagosomal degradation in primary human macrophages thereby inhibiting the intracellular killing of mycobacteria within macrophages in vivo (139). These studies highlight the role of maintaining regulated selective autophagy activity in patients with CF. If efficiently activated, selective autophagic processes facilitate removal of polyubiquitinated proteins and control infection. However, inadvertent genetic or pharmacological blockade of autophagy may put patients at risk from accumulation of protein inclusions and aggresomes, and infection from drug-resistant pathogens. Therapies that restore autophagy or enhance autophagosome clearance or activity offer great therapeutic potential in the treatment CF.

Autophagy deficiency in IPF

Oxidative stress is one important molecular mechanism underlying fibrosis in the lung. Fibrosis is characterized by the excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) protein deposition in the basement membrane and interstitial tissue of an injured epithelium and expansion of activated mesenchymal cells (i.e., myofibroblasts) (25). Lung fibroblasts are important components of the interstitium, which are principal producers of ECM and participate in wound healing. Defective fibroblast autophagic processes have been implicated in the pathogenesis of IPF. Lung tissues from IPF patients and human lung fibroblasts treated with transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) demonstrate increased cellular senescence and decreased autophagic activity as characterized by decreased LC3B protein expression (4, 130). TGF-β1 inhibits autophagy in human lung fibroblasts. Genetic deletion of the autophagy proteins, LC3 or Beclin 1, potentiated the TGF-β1-induced expression of fibronectin and the myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin in fibroblasts (130). Treatment of mice with the autophagy-inducing drug, rapamycin, partially protected against lung fibrosis (130). Loss of autophagy in patients with IPF may potentiate the effects of TGF-β1 with respect to ECM production and transformation to a myofibroblast phenotype.

Another cytokine, IL-17A can also inhibit autophagy in mouse lung epithelial cells. In a murine bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis, blocking IL-17A in the lung protects against fibrosis (109). This beneficial effect was abrogated if the animals were simultaneously treated with a chemical inhibitor of autophagy, 3-MA. Although the exact mechanism for this effect remains unclear, in the presence of IL-17A, there was a reduction in autophagy proteins (e.g., Beclin 1). Interestingly, antagonism of IL-17A restored autophagy and consequently decreased TGF-β1-induced collagen production by epithelial cells (109).

Selective autophagic processes such as reticulophagy or aggrephagy may also play a role in IPF. IPF patients have increased levels of ubiquitinated proteins and p62 (4, 130), and type II epithelial cells of patients with sporadic IPF show evidence of severe ER stress (81), a dysfunctional epithelial cell phenotype that facilitates fibrotic remodeling (86). Further experiments are needed to determine the relationships between autophagy, apoptosis, and fibrotic responses as they relate to human disease.

Autophagy and pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is defined as a sustained elevation of pulmonary arterial pressure to more than 25 mm Hg at rest or to more 30 mm Hg with exercise, with a mean pulmonary-capillary wedge pressure and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure of less than 15 mm Hg (44). PAH is a pulmonary-selective vascular remodeling disease in which cells within the vessel wall display a proliferative and anti-apoptotic phenotype (41). Initial injury and apoptosis of endothelial cells is then followed by hyperproliferation of apoptosis-resistant endothelial and smooth muscles cells. Pulmonary arterial remodeling occludes the vessel lumen that leads to right ventricular failure and premature death. Hypoxia results in secondary pulmonary hypertension (PH). Hypoxic PH is a progressive and often fatal complication of chronic lung disease (156).

In human lung tissue recovered from patients with various forms of PH, the total expression of LC3B, and the accumulation of its activated (lipidated) form LC3B-II were increased relative to normal lung tissue. The expression of LC3B was markedly increased in the endothelial cell layer, and in the adventitial and medial regions of large and small pulmonary resistance vessels from PH lung, relative to normal vascular tissue (91). Hypoxic lung tissues have increased evidence of autophagic vacuoles compared with lung tissue from normoxic mice. Compared to wild-type mice, LC3B knockout mice (LC3B−/−) display increased indices of PH, including increased right ventricular systolic pressure, and Fulton's Index relative to wild-type mice, after chronic hypoxia, (91) suggesting that the autophagy protein LC3B may exert a protective function in PH. In contrast, autophagy deficiency through the knockdown of the autophagic protein Beclin 1 resulted in improved angiogenesis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells from fetal lambs with persistent PH (172), which suggested that Beclin 1-mediated autophagy might contribute to disease progression of PH.

Recent studies demonstrate a partial inhibition of monocrotaline-induced PH in rats using chloroquine, an inhibitor of autophagy. Chloroquine protected against monocrotaline-induced PH by reducing proliferation and increasing apoptosis of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. The authors proposed a mechanism by which downregulated autophagy restores expression of bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (BMPR-II), whose depletion is implicated in PH pathogenesis (102). Additionally, application of an inhibitor of AMPK, which functions in the activation of autophagy by energy depletion, protected against hypoxia-induced PH in mice (63).

Autophagy may play a dual role in PH protection by initially protecting against endothelial cell apoptosis, but also by protecting against the apoptosis of hyperproliferating vascular cell populations. At present the reason for the contrasting observations in the different models remain unclear, but suggest that autophagy may play a complex role in PH progression by influencing both cell proliferation and apoptosis in a cell type-specific manner.

ER stress represents a common feature of many known PH-triggering or facilitating processes. In the pulmonary circulation, ER stress leads to the activation of ATF6, causing upregulation of neurite outgrowth inhibitor (Nogo), a member of the reticulin family of proteins that regulate ER shape (41). Nogo induction causes disruption of a functional ER-mitochondrial unit, resulting in decreased mitochondrial Ca2+ and inhibition of several key Ca2+-sensitive mitochondrial enzymes. The administration of the chemical chaperones, 4-phenylbutyric acid and tauroursodeoxycholic acid limit ER stress-induced mitochondrial suppression, preventing and reversing vascular remodeling in rodent models of PH (41).

PH is also associated with abnormal mitochondrial function. PH mitochondria suppress glucose oxidation and switch cellular metabolism toward glycolysis, even in normoxia. This metabolic switch favors apoptosis resistance and is typically associated with increased Ψm, decreased mROS production, activated NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) and HIF-1α even under normoxia, enhanced proliferation, and increased glucose uptake and glycolysis. Such suppression of mitochondrial function limits oxidative stress that may prevent apoptosis in the short term, and that may, if sustained, facilitate the pathogenesis of vascular remodeling diseases (40). Mitochondrial fragmentation is observed in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) of Fawn-hooded rats, which develop spontaneous PAH (14). Markers of mitochondrial fission, including dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), are also increased in PASMCs from patients and rats with PAH (106). However, the role of mitophagy in PAH remains to be explored.

Autophagy and lung cancer

Autophagy can exert a profound impact on carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Monoallelic disruption of the beclin 1 gene on chromosome 17q21 occurs in human breast, ovarian, and prostate tumors (Reviewed in Refs. 26, 143). Abnormal expression of Beclin 1 in tumor tissue has been associated with poor prognosis and aggressive tumor phenotypes (26, 94, 143). Autophagy may inhibit carcinogenesis in primary cells by preventing metabolic stress, through mitophagy and aggrephagy, and other homeostatic functions. Genetic deletion of autophagy proteins causes mitochondrial dysfunction, enhanced oxidative stress, and susceptibility to inflammation, conditions that may promote DNA damage and genetic instability (184). In established tumors, autophagy can promote survival of tumor cells. Autophagy may also contribute to acquired tumor cell resistance to chemotherapeutics, and it can also enhance chemotherapy-induced cell killing through autophagic cell death (184).

To date only few studies have examined the role of autophagy specifically in lung cancer. Beclin 1 expression was found to be inversely correlated with tumor size and primary tumor stage in human lung adenocarcinomas and reduced in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) relative to normal tissue (99, 186). Autophagy has been proposed to maintain genomic stability through the degradation of the GTPase RhoA. The elevated expression of RhoA was positively correlated with autophagic dysfunction in human lung carcinoma (10). Induction of autophagy through mTOR inhibitors has been associated with radiosensitization in NSCLC cells (75). Further, the autophagy inhibitor hydroxychloroquine has been tested for general therapeutic efficacy in NSCLC (26).

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Autophagy represents a general response to oxidative stress that functions to remove damaged subcellular substrates and to preserve mitochondrial homeostasis. While autophagy is generally considered a survival response, its relationship to cell death pathways is not entirely clear across toxicological models. In some instances, as in the case of CS exposure, autophagy has been associated with enhanced apoptosis (23, 24), whereas it can prevent apoptosis in tumor cells (184). Recent studies also suggest that autophagy profoundly impacts the regulation of inflammation and immune system functions, with diverse roles in pathogen clearance, cytokines regulation, and antigen presentation (34–36).

Autophagy may play a critical role in human diseases associated with pro-oxidant or pro-inflammatory states. Among these include diseases of the lung and lung vasculature, as highlighted in this review, cardiovascular disease (151), inflammatory bowel disease (50, 140), and cancer (184). The upregulation of autophagy is not necessarily beneficial in all diseases, and it may be associated with pathogenesis in the context of pathogen infections that use this pathway for replication, or associated with increased apoptosis in the context of CS exposure. Further understanding of the relative role of autophagy and its relationship to apoptosis and inflammation in the pathogenesis of specific diseases may be required before targeting elements of this pathway for therapy. Further elucidation of the mechanisms by which autophagy is finely regulated in a context-specific fashion may generate additional therapeutic targets.

Currently, only a few compounds that can modulate autophagy have been evaluated for clinical use, including rapamycin (an inducer of autophagy) and chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine (inhibitors of autophagy). The pleiotropic effects of these compounds complicate the interpretation that their therapeutic effects are directly related to autophagy and not to other endpoints. Additional compounds that modulate autophagy have been described, including a recently developed Tat-Beclin 1 peptide (160), trehalose (an inducer of autophagosome formation), inhibitors of histone deacetylases, AMPK activators (e.g., metformin), and vitamin D (16, 17, 26, 143). Future approaches may include drug screening for molecules that either inhibit or induce autophagy. The emergence of a second generation of such compounds may result in new avenues for therapy.

Abbreviations Used

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- ALFY

400 kDa, PI3P-binding autophagy-linked FYVE domain protein

- AMPK

5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ATF4

activating transcription factor-4

- ATF6

activating transcription factor-6

- ATG

autophagy-related gene

- BMPR-II

bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-II

- BNIP3

Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein-3

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CHOP

C/EBP homologous protein

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CS

cigarette smoke

- CSE

cigarette smoke extract

- DISC

death-inducing signal complex

- DRP1

dynamin-related protein 1

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Egr-1

early growth response-1

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FIP200

200 kDa focal adhesion kinase family interacting protein

- FoxO

Forkhead BoxO

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIF-1

hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus type 1

- IFN-α/β/γ

interferon-α/β/γ

- IL

interleukin

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- IPS

IFN-β promoter stimulator

- JNK

c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase

- Keap-1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3

- LD

lipid droplet

- LIR

LC3-interacting region

- MDA5

melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- mROS

mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

mTOR complex 1

- NBR1

neighbor of breast cancer-1, early onset [BRCA1] gene 1

- NDP52

nuclear dot protein, 52-kDa

- NLRP3

nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing family, pyrin domain containing 3

- Nogo

neurite outgrowth inhibitor

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung carcinoma

- p62 (SQSTM1)

sequestosome; 62 kDa autophagic cargo adaptor protein

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PARK2

Parkinson protein-2 (Parkin)

- PASMCs

pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells

- pDCs

plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- PERK

protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PI3KC3

class III phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PI3P

phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate

- PINK1

phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted in chromosome 10 (PTEN)-induced putative kinase 1

- Rho-A

GTPase

- RIG-I

retinoic acid-inducible gene I

- RLR

retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptor

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ssRNA

single-stranded RNA

- TG2

tissue transglutaminase-2

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor-beta-1

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- Ub

ubiquitin

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UVRAG

ultraviolet radiation resistance-associated gene protein

- VSV

vesicular stomatitis virus

- Ψm

mitochondrial membrane potential

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was from NIH grants P01 HL108801, R01-HL60234, R01-HL55330, and R01-HL079904 to A.M.K.C.

References

- 1.Abdulrahman BA, Khweek AA, Akhter A, Caution K, Kotrange S, Abdelaziz D, Hewland C, Rosales-Reyes R, Kopp B, McCoy K, Montione R, Schlesinger LS, Gavrilin MA, Wewers MD, Valvano MA, and Amer AO. Autophagy stimulation by rapamycin suppresses lung inflammation and infection by Burkholderia cenocepacia in a model of cystic fibrosis. Autophagy 7: 1359–1370, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alirezaei M, Flynn CT, Wood MR, and Whitton JL. Pancreatic acinar cell-specific autophagy disruption reduces coxsackievirus replication and pathogenesis in vivo. Cell Host Microbe 11: 298–305, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appenzeller-Herzog C. and Hall MN. Bidirectional crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and mTOR signaling. Trends Cell Biol 22: 274–282, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araya J, Kojima J, Takasaka N, Ito S, Fujii S, Hara H, Yanagisawa H, Kobayashi K, Tsurushige C, Kawaishi M, Kamiya N, Hirano J, Odaka M, Morikawa T, Nishimura SL, Kawabata Y, Hano H, Nakayama K, and Kuwano K. Insufficient autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304: L56–L69, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azad MB, Chen Y, and Gibson SB. Regulation of autophagy by reactive oxygen species (ROS): implications for cancer progression and treatment. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 777–779, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae S, Sung SH, Oh SY, Lim JM, Lee SK, Park YN, Lee HE, Kang D, and Rhee SG. Sestrins activate Nrf2 by promoting p62-dependent autophagic degradation of Keap1 and prevent oxidative liver damage. Cell Metab 17: 73–84, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baltanas FC, Casafont I, Weruaga E, Alonso JR, Berciano MT, and Lafarga M. Nucleolar disruption and cajal body disassembly are nuclear hallmarks of DNA damage-induced neurodegeneration in purkinje cells. Brain Pathol (Zurich) 21: 374–388, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bánhegyi G, Baumeister P, Benedetti A, Dong D, Fu Y, Lee AS, Li J, Mao C, Margittai E, Ni M, Paschen W, Piccirella S, Senesi S, Sitia R, Wang M, and Yang W. Endoplasmic reticulum stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1113: 58–71, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baregamian N, Song J, Bailey CE, Papaconstantinou J, Evers BM, and Chung DH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 control reactive oxygen species release, mitochondrial autophagy, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase/p38 phosphorylation during necrotizing enterocolitis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2: 297–306, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belaid A, Cerezo M, Chargui A, Corcelle-Termeau E, Pedeutour F, Giuliano S, Ilie M, Rubera I, Tauc M, Barale S, Bertolotto C, Brest P, Vouret-Craviari V, Klionsky DJ, Carle GF, Hofman P, and Mograbi B. Autophagy plays a critical role in the degradation of active RHOA, the control of cell cytokinesis and genomic stability. Cancer Res. 73:4311–4322, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bence NF. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science 292: 1552–1555, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betin VM. and Lane JD. Caspase cleavage of Atg4D stimulates GABARAP-L1 processing and triggers mitochondrial targeting and apoptosis. J Cell Sci 122: 2554–2566, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodas M, Tran I, and Vij N. Therapeutic strategies to correct proteostasis-imbalance in chronic obstructive lung diseases. Curr Mol Med 12: 807–814, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnet S, Michelakis ED, Porter CJ, Andrade-Navarro MA, Thébaud B, Bonnet S, Haromy A, Harry G, Moudgil R, McMurtry MS, Weir EK, and Archer SL. An abnormal mitochondrial-hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha-Kv channel pathway disrupts oxygen sensing and triggers pulmonary arterial hypertension in fawn hooded rats: similarities to human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 113: 2630–2641, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boya P, González-Polo RA, Casares N, Perfettini JL, Dessen P, Larochette N, Métivier D, Meley D, Souquere S, Yoshimori T, Pierron G, Codogno P, and Kroemer G. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 25: 1025–1040, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell GR. and Spector SA. Hormonally active vitamin D3 (1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol) triggers autophagy in human macrophages that inhibits HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem 286: 18890–18902, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell GR. and Spector SA. Vitamin D inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in macrophages through the induction of autophagy. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002689, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cebollero E, Reggiori F, and Kraft C. Reticulophagy and ribophagy: regulated degradation of protein production factories. Int J Cell Biol 2012: 182834, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]