Abstract

We have synthesized photolabile 7-diethylamino coumarin (DEAC) derivatives of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). These caged neurotransmitters efficiently release GABA using linear or nonlinear excitation. We used a new DEAC-based caging chromophore that has a vinyl acrylate substituent at the 3-position that shifts the absorption maximum of DEAC to about 450 nm and thus is named “DEAC450”. DEAC450-caged GABA is photolyzed with a quantum yield of 0.39 and is highly soluble and stable in physiological buffer. We found that DEAC450-caged GABA is relatively inactive toward two-photon excitation at 720 nm, so when paired with a nitroaromatic caged glutamate that is efficiently excited at such wavelengths, we could photorelease glutamate and GABA around single spine heads on neurons in brain slices with excellent wavelength selectivity using two- and one-photon photolysis, respectively. Furthermore, we found that DEAC450-caged GABA could be effectively released using two-photon excitation at 900 nm with spatial resolution of about 3 μm. Taken together, our experiments show that the DEAC450 caging chromophore holds great promise for the development of new caged compounds that will enable wavelength-selective, two-color interrogation of neuronal signaling with excellent subcellular resolution.

Keywords: two-photon uncaging, GABA, wavelength-selective photolysis, pyramidal neurons

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system.1−3 GABAergic postsynaptic receptors are ionotropic chloride channels (mainly GABA-A receptors with some GABA-C receptors) and 7-transmembrane metabotropic receptors (GABA-B receptors). GABA-A receptors are pentameric, with 16 different subunits known giving rise to at least 20 widely distributed subtype combinations.1 This postsynaptic diversity is mirrored by an equally large array of different neurons that release GABA.23 Activation of GABA receptors typically generates a shunting conductance and hyperpolarizes the membrane potential, thus inhibiting neuronal activity. Several diseases of the central nervous system are associated with perturbed GABAergic inhibition, making GABA-A receptors important pharmacological therapeutic targets.1

Optical stimulation of postsynaptic receptors using caged neurotransmitters has been widely used to study the functional distribution and connectivity of neurons in both neuronal culture systems and ex vivo (i.e., brain slices).4,5 This technique is very powerful for neurophysiology as it enables the extremely rapid and local application of endogenous transmitter at a visually designated position across the cell surface or within a complex neuronal circuit. Furthermore, computer controlled lasers allow either large6 or fine scaled7 mapping to be targeted to many 100s or even 1000s of points within one experiment.5 Until recently, such experiments for GABA were limited to more low-resolution mapping using one-photon photolysis, but in 2010 we reported the first examples of two-photon uncaging of GABA.8,9 Excitation of one of these probes, CDNI-GABA, at 720 nm with a femtosecond pulsed laser produced rapid GABA-A specific currents that were, for the first time, highly localized to individual postsynaptic clusters.9 Recently, we used this method to show that functional GABA-A receptors are localized on the tips of spine heads on layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons.10 In addition to these recent developments, over 50 reports by more than 20 different research groups have appeared using two-photon photolysis of caged glutamate probes.4 Almost all these studies have been performed with short wavelengths of light, with ranges of approximately 350–410 nm for one-photon and 710–740 nm for two-photon excitation.4 In this report, we describe the synthesis and application of caged GABA probes, based on our newly developed diethylaminocoumarin(DEAC)450 caging chromophore,11 that undergo effective photolysis at wavelengths of light that are complementary to those used traditionally. DEAC450-caged GABA is photoactive using linear excitation with visible light (λmax ca. 450 nm, Scheme 1) and has a quantum yield of photolysis of 0.39. It also undergoes nonlinear (or two-photon) effective excitation at 900 nm. Here we show that these properties allow wavelength-selective one- and two-photon photolysis of DEAC450-GABA derivatives on living neurons in brain slices so as to produce local modulation of membrane potential at spine heads and around cell somata, confirming that DEAC450 is a uniquely powerful chromophore for chromatically selective uncaging experiments.

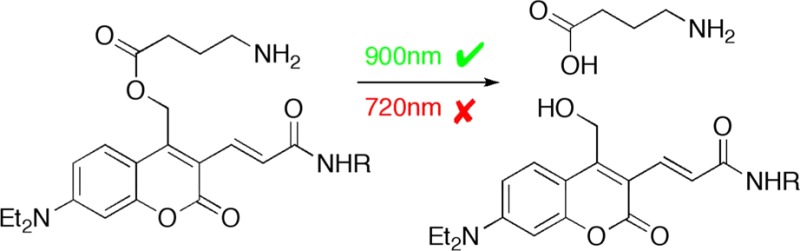

Scheme 1. DEAC450-Caged GABA Synthesis.

(a) Reagents and conditions: 2 and 3 are from ref (11) (Reprinted with permission from ref (11). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society); (b) BOC-GABA, EDC, DMAP, 84%, TFA then HPLC, 50%; (c) O-(aminoethyl)-2-azidoethyl-pentaethylene glycol, EDC, DMAP, 94%; (d) TBAF, 83%; (e) BOC-GABA, EDC, DMAP, 94%, TFA then HPLC, 73%. (b) Absorption spectra of DEAC450-GABA derivatives (1, red and 6, blue) and CDNI-Glu (violet).

Results and Discussion

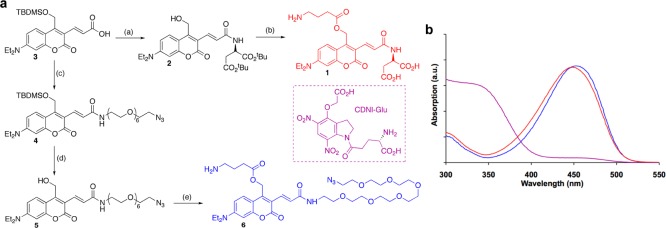

Synthesis and Chemical Properties

We synthesized two DEAC450-GABA derivatives as outlined in Scheme 1. Compound 1 was made from the known alcohol112 by EDC coupling of BOC-GABA followed by deprotection with TFA to give the d-aspartate DEAC450-GABA derivative in 42% yield after HPLC purification. Since 1 had somewhat limited solubility of only a few millimolar and was highly antagonistic toward GABA-A receptors (Figure 1c), we also synthesized a more water-soluble polyethyleneglycol (PEG) derivative to mitigate these problems. Starting with the known11 precursor of 2, O-(aminoethyl)-2-azidoethyl-pentaethylene glycol was conjugated to acid 3 to give 4 and the TBDMS protecting group was removed to give alcohol 5. Again BOC-GABA was conjugated to the alcohol, the product treated with TFA, and the reaction mixture purified by HPLC to compound 6 in 73% overall yield. The PEG-DEAC450-GABA derivative, 6, was soluble up to at least 50 mM in HEPES buffered saline without the addition of any organic cosolvent. Both derivatives had chemical properties similar to DEAC450-Glu11 in that they were found to be highly stable at physiological pH. The compounds also had similar absorption maxima and minima (Scheme 1b) and were photolyzed very efficiently with blue light (quantum yield of 0.39). Compound 6 was found to have significantly reduced antagonism toward GABA-A receptors compared to compound 1; the EC50’s for blocking evoked inhibitory synaptic current in layer 2/3 pyramidal cells were about 11 and 0.5 μM respectively (Figure 1). Thus, all subsequent physiological assays were therefore conducted with the PEG-DEAC450-GABA derivative, 6. There have been several reports of antagonism of caged neurotransmitters toward GABA-A receptors,9,11−15 and all probes tested show significant blockade of synaptic currents. These caged probes have a wide variety of chemical structures, one that is mirrored by the structural diversity of drugs clinically prescribed to treat GABA-receptor related illnesses,1 and suggests that complete removal of such antagonism is a serious challenge for caged GABA probes.15

Figure 1.

GABA-A receptor photoactivation pharmacology and antagonism of DEAC450-GABA derivatives. (a) Photolysis of 6 with 473-nm-light (1 ms, 2 mW, arrow) evokes an outward synaptic current in a CA1 pyramidal neuron that is blocked by picrotoxin (b). Compound 6 was bath applied at 10 μM, and subsequently picrotoxin was bath applied at 50 μM to the same brain slice. (c) Caged compounds were bath applied at a series of concentrations to acutely isolated brain slices and the blockade of synaptically evoked inhibitory currents in layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons was monitored by whole-cell patch-clamp. Red, blue, and violet curves correspond to 1, 6, and CDNI-Glu, respectively.

Photolysis of DEAC450-GABA with Visible Light Specifically Evokes Large Inhibitory Synaptic Currents

We tested if photolysis of DEAC450-GABA evoked currents that were specific to GABA-A receptors by applying compound 6 at a concentration of 10 μM to acutely prepared mouse brain slices. Irradiation of a patch-clamped CA1 cell body with a 1 ms pulse from a 473 nm laser produced a robust outward current (Figure 1a) which was blocked by bath application of picrotoxin (50 μM), a specific antagonist of GABA-A receptors1 (Figure 1b). No evoked currents were observed in the absence of photolysis and irradiation of cells with blue light alone did not evoke any current (data not shown). Next, we studied the spatial resolution available from one-photon uncaging of DEAC450-GABA. The 473 nm laser was directed to a series of points moving away from a cell body (Figure 2a). When the laser beam was on or close to the cell soma, it was possible to evoke outward currents of hundreds of picoamperes, this current fell almost to zero at a distance of 70–80 μm from the center of the soma (Figure 2b). A similar space constant was observed for one-photon uncaging on dendrites (Figure 2c), albeit with smaller currents being evoked overall (Figure 2d).

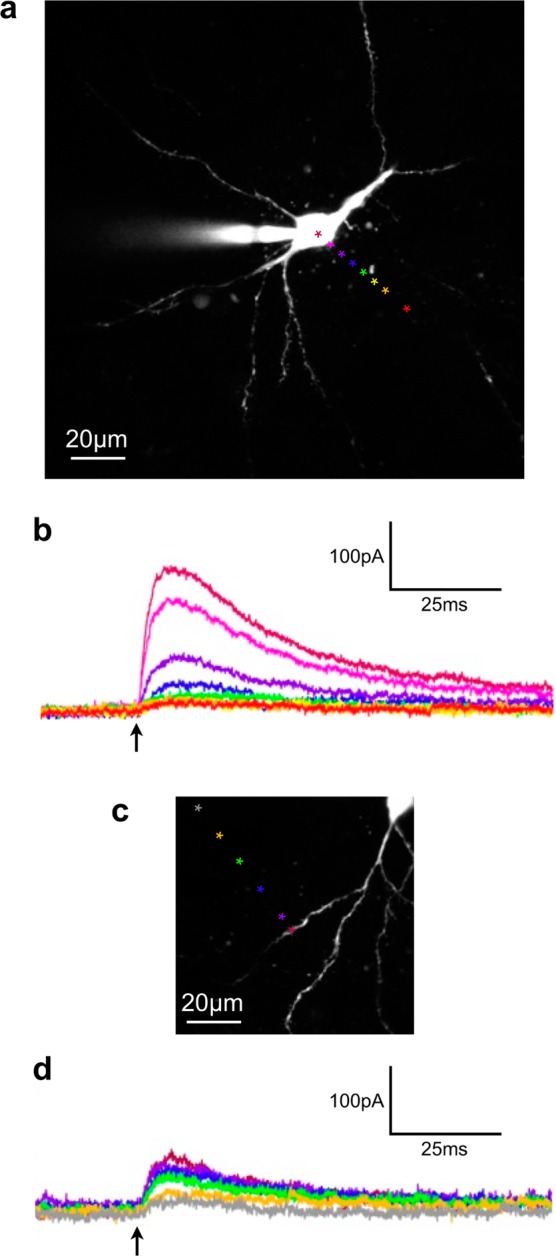

Figure 2.

Spatial resolution of one-photon uncaging of compound 6 with 473 nm light. Compound 6 was bath applied at 10 μM to an acutely isolated brain slice and photolyzed (arrows) with a continuous wave, 473 nm laser (1 ms, 2mW) centered at the indicated points. (a) Two-photon fluorescence image of a CA1 pyramidal neuron with the positions of uncaging marked. (b) The outward current traces corresponding to each point in (a). (c) Two-photon fluorescence image of a CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Alexa-594 with the positions of uncaging marked on or near an isolated dendrite (d) The outward current traces corresponding to each point in (c). Cells filled with Alexa-594 were imaged at 1075 nm.

It should be noted that since DEAC450 is a coumarin derivative, it does have the expected fluorescence emission in the blue-green wavelength range. For two-photon excitation, this fluorescence reaches a maximum at 900 nm and falls to zero at 1000 nm. At 720 nm, it is 64-fold lower than its peak.11 We found that we could cleanly image cells filled with Alexa-594, with no background signal, using two-photon excitation at 1075 nm. However, “standard” two-photon Ca2+ imaging methods at 800–840 nm10,16 are problematic using bath applied DEAC450 cage, thus for such experiments the relatively nonfluorescent RuBi-GABA10,12 is to be preferred to DEAC450-GABA. Recently developed long wavelength Ca2+ dyes may be of utility with DEAC450 caged compounds.17

Photolysis of DEAC450-GABA with Visible Light Blocks Action Potentials

Next we examined if one-photon photolysis of DEAC450-GABA could generate sufficient neuronal hyperpolarization to block action potentials. Current injection of 500 pA for 2 ms into a CA1 pyramidal cell via a patch pipet elicited action potential spikes (green traces, Figure 3). If a flash from a 473 nm laser was targeted to the cell body just before current injection, such spikes were reliably blocked by DEAC450-GABA uncaging (red traces, Figure 3). Firing and blocking could be interleaved in a highly reproducible manner; the membrane potential traces in Figure 3 show such an input train.

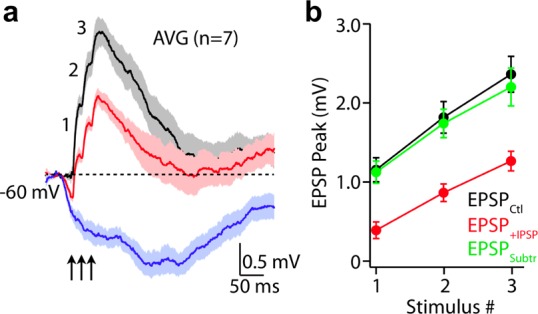

Figure 3.

Uncaging of compound 6 blocks action potentials. Irradiation of a CA1 pyramidal cell body with a light flash from a 473 nm laser (blue circle) induces sufficient hyperpolarization to block action potentials (red traces) evoked by current injection (500 pA, 2 ms, green arrow) from a patch-clamp pipet (green traces). Membrane potential was monitored in a CA1 pyramidal cell in an acutely isolated brain slice filled with Alexa-594 imaged at 1075 nm. Compound 6 was bath applied at 10 μM, and uncaging (1 ms, 2mW) was triggered just prior to current injection as indicated by the blue and green arrows. Action potential firing and blockade were recorded with interleaved timing several times in the same cell.

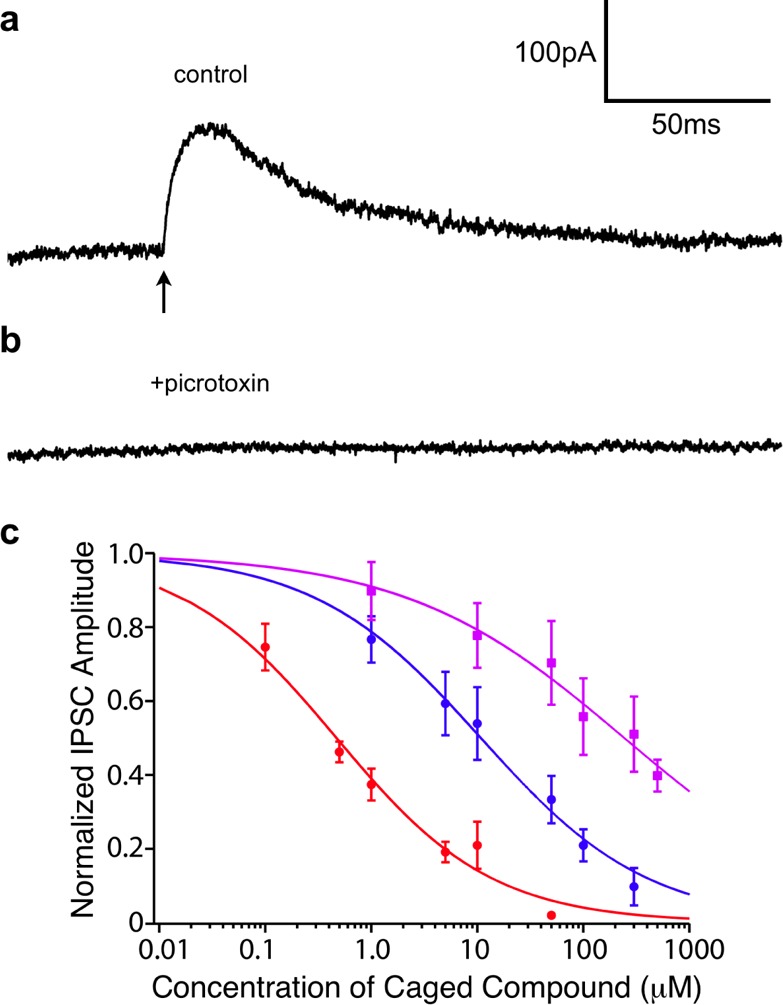

Two-Color Photolysis of Glutamate and GABA Locally Controls Dendritic Membrane Potentials

Since DEAC450 is relatively inactive toward two-photon excitation at 720 nm,11 we examined if DEAC450-GABA could be paired with a caged glutamate probe that is highly active at such short wavelengths, so as to enable wavelength-selective uncaging of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. We coapplied compound 6 and CDNI-Glu18 to a brain slice at 0.015 and 10 mM, respectively. Three spine heads on a patch-clamped layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron were irradiated with 720 nm light from a Ti:sapphire laser so as to evoke membrane depolarizations similar in size to miniature excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs, Figure 4, black traces). If such light flashes were preceded by irradiation with blue light, there was a significant decrease in the evoked EPSPs (Figure 4, red traces). When 473 nm light was applied to the sample in the absence of accompanying two-photon flash photolysis, only inhibitory postsynaptic potentials were detected (Figure 4, blue traces). Note the absorption peak in this region for CDNI-Glu (Scheme 1b) is due to a small impurity. HPLC analysis of samples of CDNI-caged compounds irradiated at 473 nm show no photolysis (Matt Banghart, personal communication). Since the concentration of compound 6 used for experiments in Figure 4 is 13-fold lower and the energy at 720 nm is 50% less than those used for two-photon photolysis of compound 6 (see below), our data show that CDNI-Glu and DEAC450-GABA can be photolyzed with excellent chromic orthogonality using two-photon excitation at 720 nm and one-photon excitation at 473 nm, respectively.

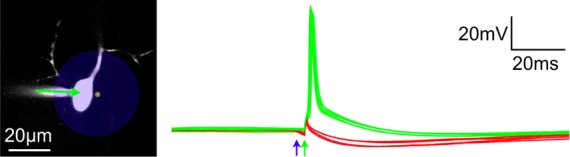

Figure 4.

Two-color uncaging of glutamate and GABA at spine heads. Compound 6 was bath applied to acutely isolated brain slices at 15 μM, and CDNI-Glu was applied by local perfusion from a pipet just above the brain slice at 10 mM. Currents evoked in pyramidal neuron were monitored in cells via whole-cell patch-clamp. Uncaging was effected by continuous wave 473 nm laser and a femtosecond pulsed Ti:sapphire laser tuned to 720 nm directed to three spine heads. (a) Potentials evoked by three uncaging events at 720 nm (average of 7 trials, 30–40 mW, 0.5 ms) without (black) or with (red) GABA uncaging. Irradiation with 473 nm light (1–2 mW, 5 ms, arrows) preceded the two-photon uncaging by 20 ms. Blue trace show the potentials evoked by GABA uncaging alone. (b) Graph of the evoked excitatory potentials in the absence (black) and presence (red) of GABA uncaging. Subtraction of the blue trace from the red trace in (a) is shown in green. The overlay of black and green plots indicates linear summation of inputs.

Wavelength-Selective, Two-Photon Photolysis of GABA at 900 nm

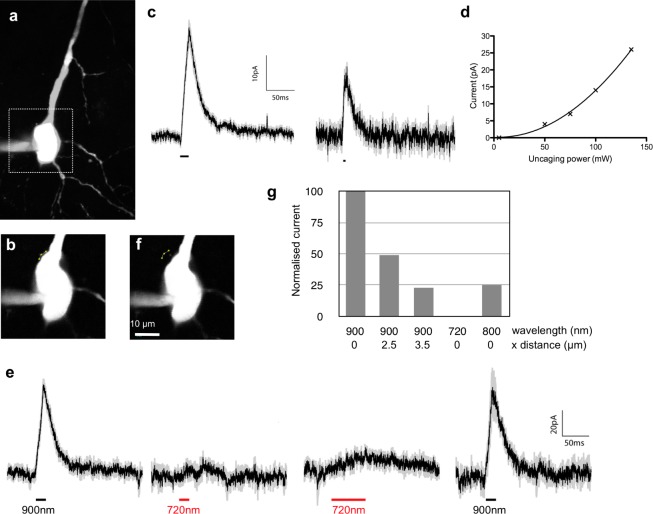

Finally, we tested the ability of the DEAC450-GABA derivative 6 to undergo useful two-photon uncaging at specific wavelengths using a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser. Compound 6 was bath-applied to brain slices at 0.2 mM, and CA1 neurons were filled with red fluorescent dye via a patch pipet and imaged at 1075 nm (Figure 5a). This allowed us to position three uncaging spots on the perimeter of the soma (Figure 5b) where irradiation at 900 nm (100 mW, 5 ms per point) generated rapid outward currents (Figure 5c, n =61, from 4 cells). Reducing the flash duration to 1 ms produced smaller but faster currents (Figure 5c, right), as did irradiation of one point for 1 ms with 100 mW (data not shown). These currents were produced by two-photon excitation, as a power dosage curve for evoked currents was well fit by a quadratic function (Figure 5d). The most robust currents were consistently generated by irradiation of three points for 5 ms, so we used this uncaging protocol to explore wavelength selectivity and spatial resolution. We found that DEAC450-GABA (6) could be uncaged with excellent two-photon uncaging wavelength selectivity. Figure 5e shows the current traces from a sequence of uncaging events when a laser tuned to 900 nm was focused adjacent to the soma (Figure 5b) to evoke signals of 60 pA (n = 5). The same power dosage at 720 nm evoked no signals (n = 3), and even increasing the irradiation period 4-fold had little or no effect (n = 3). Returning to the same points with the 900 nm beam restored the original signal (n = 4). We also tested the spatial resolution of such optical initiated inhibitory currents. We found that moving the excitation beam 3.5 μm laterally from the cell perimeter (Figure 5f) produced currents that were 23% of the maximum (Figure 5g). We found with single point irradiation signals were indistinguishable from background between 1.5 and 3 μm laterally from the soma (data not shown). Note that uncaging at 800 nm evoked currents that were of intermediate value to those at 720 and 900 nm.

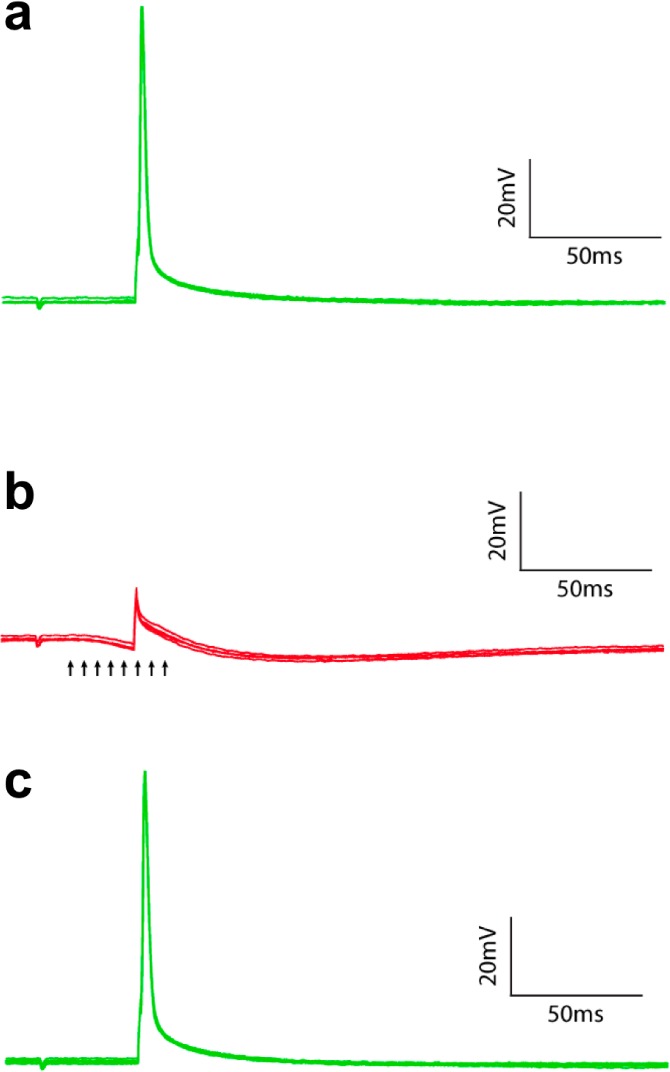

Figure 5.

Wavelength-selective two-photon uncaging of GABA. Compound 6 was bath applied to acutely isolated brain slices at 200 μM. Currents evoked in CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with Alexa-594 (100 μM) were monitored via whole-cell patch-clamp. Uncaging was effected by two femtosecond-pulsed Ti:sapphire lasers tuned to 900 and 720 nm directed close to the cell which was imaged with a third laser at 1075 nm. (a) Two-photon fluorescence image of neuron (2D maximum projection of 15 z-sections, boxed area shown in (b) and (f)). (b) Reference image showing the position of three uncaging points close to the soma. (c) Currents evoked by three 100 mW uncaging events at 900 nm for 5 ms (n = 61) and 1 ms (n = 11). (d) Plot of power dosage versus evoked current was fit with a quadratic function implying uncaging was through two-photon excitation. (e) Current traces evoked by uncaging at 900 or 720 nm. Black traces are an average of 3–5 uncaging trials with the SE shown in gray. (f) Reference image showing the irradiation points 3.5 μm from the cell used to test the lateral uncaging resolution. (g) Summary of the effects of uncaging on and close to the soma with lasers tuned to 900, 800, and 720 nm at defined lateral distances from the cell body.

The difference in resolution between one-photon uncaging using 473-nm light (Figure 2) and two-photon uncaging at 900 nm (Figure 5) is highly significant, and illustrates the reason why the latter is useful for studying the details of subcellular signaling in living tissue. We believe that two-photon uncaging of DEAC450-GABA (6) required high energy because the probe must to be used at a concentration that is highly antagonistic toward its target receptors (Figure 1c). Nevertheless DEAC450-GABA is sufficiently photoactive so as to allow uncaging of enough GABA to counteract such antagonism (Figure 5c). Furthermore, the wavelength selectivity observed for this probe (Figure 5e) confirms that reported for DEAC450-Glu.11 We do not believe than any one wavelength is ideal for two-photon photolysis of caged neurotransmitters,15 however, since short wavelengths of near-IR light (710–740 nm range) have been used for two-photon release of many signaling molecules in brain slices (e.g., glutamate,18,19 GABA,9 calcium,19 IP320,21), we suggest that DEAC450-caged compounds are a useful addition to the optical toolbox available to neurophysiologists as their chromatic activity is highly complementary to well established nitroaromatic caged probes.

Two-Photon Uncaging of DEAC450-GABA at 900 nm Blocks Action Potentials

It is known that the output of individual interneurons onto pyramidal cells is sufficient to block action potentials.22 Thus we tested the ability of two-photon photolysis of compound 6 to mimic such synaptically evoked effects. As before (Figure 3), we used current injection to fire actions potentials in CA1 pyramidal cells (Figure 6a). Targeting the proximal part of the axon22 with the 900 nm laser (100 mW, 5 ms per point) could evoke inhibitory currents that were sufficient to block induced action potentials (Figure 6b). When there was no uncaging, action potential firing was restored (Figure 6c). The advantage of two-photon uncaging in comparison to one-photon uncaging is that the former allows us to stimulate subcellular locations much more precisely than the latter. Since it is known that different types of inhibitory interneurons target different parts of the cell,2 two-photon photolysis of DEAC450-caged GABA could be used to mimic artificially such spatially segregated inputs.22

Figure 6.

Two-photon uncaging of DEAC450-GABA blocks actions potentials. Irradiation of a around the axon most proximal to a CA1 pyramidal cell body with a Ti:Sapphire laser tuned to 900 nm induced sufficient hyperpolarisation to block action potentials (red traces) evoked by current injection from a patch-clamp pipet (green traces). Compound 6 was bath applied at 200 μM, and uncaging (5 ms, 100 mW) was triggered (arrows) during current injection. (a) Current injection (500 pA, 2 ms) induced an action potential (n = 5). (b) Uncaging GABA consistently blocked action potential firing (n = 5). (c) Removal of block restored action potential firing (n = 5).

Conclusion

We have synthesized new caged GABA probes based on our DEAC450 caging chromophore.11 A useful feature of the DEAC450 scaffold is the pendant carboxylate, which allows attachment of various substituents with different chemical characteristics. We found that a negatively charged derivative (1) was about 20-fold more antagonistic toward GABA-A receptors than a neutral polyethyleneglycol (PEG) derivative (6). The EC50 for blockade of evoked inhibitory currents of the PEG derivative of DEAC450-caged GABA (6) was 11 μM. This antagonism was sufficiently low to allow highly efficient uncaging of GABA with a continuous-wave visible-light laser so as to generate large synaptic currents. We confirmed11 that the DEAC450 caging chromophore is highly active toward two-photon excitation using a femtosecond-pulsed laser at 900 nm but relatively much less active at 720 nm. Taken together, our experiments show that the DEAC450 caging chromophore holds great promise for the development of new caged neurotransmitters that will enable chromatically selective, two-color, two-photon interrogation of neuronal signaling with excellent subcellular resolution.

Methods

Synthesis and Photochemical Methods

Full details of the synthesis are described in the Supporting Information. The quantum yield of uncaging was measured by comparative photolysis as described previously for other caged compounds.11 Concentrations of DEAC450-Glu and DEAC450-GABA were set to give an OD = 0.2 at 473 nm in a 1 mm cuvette. A defocused 473 nm laser was used for irradiation. DEAC450-Glu has a quantum yield of photolysis of 0.39. HPLC analysis was used to follow the time course of extent of reaction that both caged compounds.

Animals and Brain Slice Preparation

All animal handling was performed in accordance with NIH guidelines approved by institutional (Mount Sinai and Yale) IACUC review. Under isoflurane anesthesia, mice were decapitated and coronal or transverse brain slices (300–350 μm thick) were cut as described previously10,23 in one of two ice-cold external solutions containing (in mM): 110 choline Cl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 7 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 20 glucose, 11.6 sodium ascorbate, 3.1 sodium pyruvate or 124 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1 KCl, 2 K H2PO4, 10 glucose, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2. Both solutions were bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Slices were then transferred to artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 127 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2 and 20 glucose, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After an incubation period of 30 min at 34 °C, the slices were maintained at 20–22 °C for at least 20 min until use.

Two-Photon Microscopy and Physiology

Imaging and uncaging experiments were performed as described previously.10,23 For experiments in Figures 1–3, 5 and 6, an Olympus BX61 microscope (Penn Valley, PA) fitted with a Prairie Technologies (Middleton, WI) Ultima dual-galvo scan head and three Ti:sapphire lasers (Coherent, Palo Alto, CA), an EPC9 amplifier (Heka Instruments, Bellmore, NY), and an Olympus 60× lens (LUMFLN60XW, 1.1 NA) was used. For experiments in Figure 4, imaging was performed with a custom-built microscope including an Olympus BX51 microscope fitted with a single-galvo scanhead made by Mike’s Machine Company (Attleboro, MA) and two Ti:sapphire lasers (Coherent), a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), and an Olympus 60× lens (LUMPLFL60XW/IR2 0.9 NA) was used. Both microscopes also had a continuous-wave 473-nm laser for visible light uncaging. Experiments were conducted at room temperature (22–24 °C), except where noted, in a submersion-type recording chamber. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained from cortical pyramidal cells (CA1 or prefrontal layer 2/3) identified with IR differential interference contrast microscopy. Patch-clamp recordings were made with glass electrodes (3–5 MΩ) filled with (in mM) KMeSO3 or potassium gluconate (135), HEPES (10), MgCl2 (4), Na2ATP (4), NaGTP (0.4), Alexa-594 (0.01–0.1) and sodium creatine phosphate (10), adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH. For determination of GABA-A receptor block, inhibitory postsynaptic currents were evoked in layer 2/3 neurons using local electrical stimulation and compounds were bath applied at a range of concentrations (0.001–1.0 mM). Off-line analysis was performed using MATLAB and IgorPro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (GM053395 and NS069720 to G.C.R.E.-D., MH099045 to M.J.H.) and the HFSP (RG0089/2009C to G.C.R.E.-D.).

Supporting Information Available

Full synthesis details for the studied compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

J.P.O. made and characterized the new compounds. J.M.A. performed the experiments in Figures 1ab, 2, 3, 5. and 6. C.Q.C., G.L., and M.J.H. designed and performed the experiments in Figure 1c and Figure 4, G.C.R.E.-D. designed the DEAC450 caging chromophore and wrote the paper. All authors approved the submission. G.C.R.E.-D. thanks Craig Deitelhoff (Prairie Technologies) for help in the original configuration of the three-laser, two-photon microscope used in Figure 5.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Möhler H. (2006) GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 326, 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P.; Klausberger T. (2005) Defined types of cortical interneurone structure space and spike timing in the hippocampus. J. Physiol. (London, U.K.) 562, 9–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli G. A.; Alonso-Nanclares L.; Anderson S. A.; Barrionuevo G.; Benavides-Piccione R.; Burkhalter A.; Buzsaki G.; Cauli B.; Defelipe J.; Fairen A.; Feldmeyer D.; Fishell G.; Fregnac Y.; Freund T. F.; Gardner D.; Gardner E. P.; Goldberg J. H.; Helmstaedter M.; Hestrin S.; Karube F.; Kisvarday Z. F.; Lambolez B.; Lewis D. A.; Marin O.; Markram H.; Munoz A.; Packer A.; Petersen C. C.; Rockland K. S.; Rossier J.; Rudy B.; Somogyi P.; Staiger J. F.; Tamas G.; Thomson A. M.; Toledo-Rodriguez M.; Wang Y.; West D. C.; Yuste R. (2008) Petilla terminology: nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nat. Rev. 9, 557–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Davies G. C. R. (2013) A chemist and biologist talk to each other about caged neurotransmitters. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 9, 64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder M.; Zieglgansberger W.; Dodt H. U. (2004) Shining light on neurons—elucidation of neuronal functions by photostimulation. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 167–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway E. M.; Katz L. C. (1993) Photostimulation using caged glutamate reveals functional circuitry in living brain slices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 7661–7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R.; Nemoto T.; Miyashita Y.; Iino M.; Kasai H. (2001) Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantevari S.; Matsuzaki M.; Kanemoto Y.; Kasai H.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R. (2010) Two-color, two-photon uncaging of glutamate and GABA. Nat. Methods 7, 123–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M.; Hayama T.; Kasai H.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R. (2010) Two-photon uncaging of gamma-aminobutyric acid in intact brain tissue. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 255–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C. Q.; Lur G.; Morse T. M.; Carnevale N. T.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R.; Higley M. J. (2013) Compartmentalization of GABAergic inhibition by dendritic spines. Science 340, 759–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson J. P.; Kwon H. B.; Takasaki K. T.; Chiu C. Q.; Higley M. J.; Sabatini B. L.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R. (2013) Optically selective two-photon uncaging of glutamate at 900 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5954–5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rial Verde E. M.; Zayat L.; Etchenique R.; Yuste R. (2008) Photorelease of GABA with Visible Light Using an Inorganic Caging Group. Front. Neural Circuits 2, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár P.; Nadler J. V. (2000) gamma-Aminobutyrate, α-carboxy-2-nitrobenzyl ester selectively blocks inhibitory synaptic transmission in rat dentate gyrus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 391, 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo F. F.; Papageorgiou G.; Corrie J. E.; Ogden D. (2009) Laser photolysis of DPNI-GABA, a tool for investigating the properties and distribution of GABA receptors and for silencing neurons in situ. J. Neurosci. Methods 181, 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato L.; Mourot A.; Davenport C. M.; Herbivo C.; Warther D.; Leonard J.; Bolze F.; Nicoud J. F.; Kramer R. H.; Goeldner M.; Specht A. (2012) Water-soluble, donor-acceptor biphenyl derivatives in the 2-(o-nitrophenyl)propyl series: highly efficient two-photon uncaging of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid at lambda = 800 nm. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 1840–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley M. J.; Sabatini B. L. (2008) Calcium signaling in dendrites and spines: practical and functional considerations. Neuron 59, 902–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa T.; Hanaoka K.; Koide Y.; Ujita S.; Takahashi N.; Ikegaya Y.; Matsuki N.; Terai T.; Ueno T.; Komatsu T.; Nagano T. (2011) Development of a far-red to near-infrared fluorescence probe for calcium ion and its application to multicolor neuronal imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 14157–14159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Davies G. C. R.; Matsuzaki M.; Paukert M.; Kasai H.; Bergles D. E. (2007) 4-Carboxymethoxy-5,7-dinitroindolinyl-Glu: an improved caged glutamate for expeditious ultraviolet and two-photon photolysis in brain slices. J. Neurosci. 27, 6601–6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. R.; Choi H. B.; Rungta R. L.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R.; MacVicar B. A. (2008) Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature 456, 745–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantevari S.; Hoang C. J.; Ogrodnik J.; Egger M.; Niggli E.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R. (2006) Synthesis and two-photon photolysis of 6-(ortho-nitroveratryl)-caged IP3 in living cells. ChemBioChem 7, 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. R.; Iremonger K. J.; Kantevari S.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R.; MacVicar B. A.; Bains J. S. (2009) Astrocyte-mediated distributed plasticity at hypothalamic glutamate synapses. Neuron 64, 391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg G.; Markram H. (2007) Disynaptic inhibition between neocortical pyramidal cells mediated by Martinotti cells. Neuron 53, 735–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantevari S.; Buskila Y.; Ellis-Davies G. C. R. (2012) Synthesis and characterization of cell-permeant 6-nitrodibenzofuranyl-caged IP3. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 11, 508–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.