Abstract

Dentigerous cyst (DC) is one of the most common odontogenic cysts of the jaws and rarely recurs. On the other hand, keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT), formerly known as odontogenic keratocyst (OKC), is considered a benign unicystic or multicystic intraosseous neoplasm and one of the most aggressive odontogenic lesions presenting relatively high recurrence rate and a tendency to invade adjacent tissue. Two cases of these odontogenic lesions occurring in children are presented. They were very similar in clinical and radiographic characteristics, and both were treated by marsupialization. The treatment was chosen in order to preserve the associated permanent teeth with complementary orthodontic treatment to direct eruption of the associated permanent teeth. At 7-years of follow-up, none of the cases showed recurrence.

Keywords: Dentigerous cyst; Odontogenic cyst; Odontogenic tumors; Decompression, surgical

INTRODUCTION

The frequency of odontogenic cysts in children is relatively low. It has been estimated that about 4%-9% of dentigerous cysts occur in the first decade of life3,13. Keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT) presents most frequently in the second, third and fourth decades of life (54.2%) with rare cases reported as early as the first, and as late as the ninth decade of life2,12. Removal of the entire cyst associated with the extraction of the impacted tooth is the main treatment to prevent recurrence of odontogenic cystic lesions. However, when there is a possibility of preservation and eruption of those teeth, conservative treatment should be the choice. Treatment of KCOTs remains a controversial subject because of their great potential to recur2,3,5,8,12. Sometimes, the first surgical approach in KCOT is decompression or marsupialization and when it gains reduced volume, enucleation has to be performed5,8.

This paper presents two cases of odontogenic lesions in children, one dentigerous cyst and one keratocystic odontogenic tumor, which were treated by marsupialization in order to preserve the associated permanent teeth.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

An 8-year-old boy was referred to the Department of Oral Surgery with chief complaint of volume augmentation at the left side of mandible, pain and fever for about one week. Panoramic radiograph revealed a unilocular radiolucent cystic lesion with sclerotic border associated lateral incisor, canine, first and second premolar crowns. Teeth were dislocated apically and medially. After local bone aspiration and incisional biopsy, the histological diagnosis of dentigerous cyst was established (Figure 1). Analysis of capsule fragment showed to be lined by non-keratinized epithelium. Hemorrhagic areas were also present. Under local anesthesia, the patient was submitted to marsupialization after extraction of the primary molars (Figure 2a). The oral mucosa was sutured to the cyst capsule and iodoform gauze dressing was inserted within lesion cavity. Medication gauze was changed every 5 days until the wound edges were epithelialized and afterwards an acrylic plug was inserted in order to keep wound opening and decompression. The parents were instructed to irrigate the cavity twice a day with saline solution and the acrylic plug was fitted when necessary, attending lumen reduction. Radiographic follow-up was performed periodically. The involved permanent teeth erupted naturally, without any traction forces (Figure 2b). Second premolar assumed an impacted position over the first premolar probably because of dental arch space deficiency. Thus, under local anesthesia the second premolar was removed. One year after the first visit, the lesion had completely withdrawn, but the lateral incisor still remained displaced. A space-maintainer was installed and the patient was referred to orthodontic treatment (Figure 2c) for correcting tooth position. The radiographic follow-up of 7 years showed no lesion recurrence (Figure 2d).

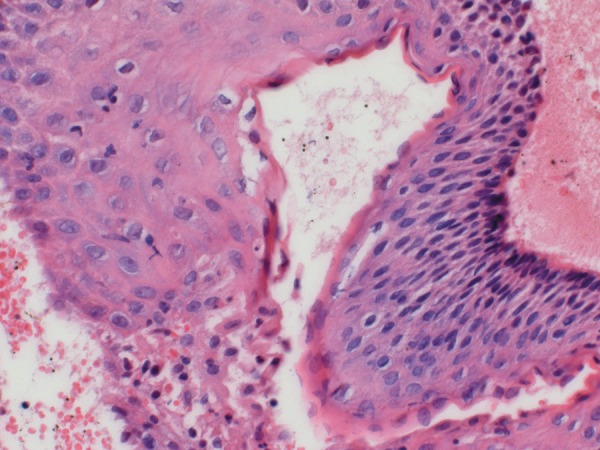

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of the lesion showing the cystic lesion lined by non-keratinized epithelium and hemorrhagic areas (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x200)

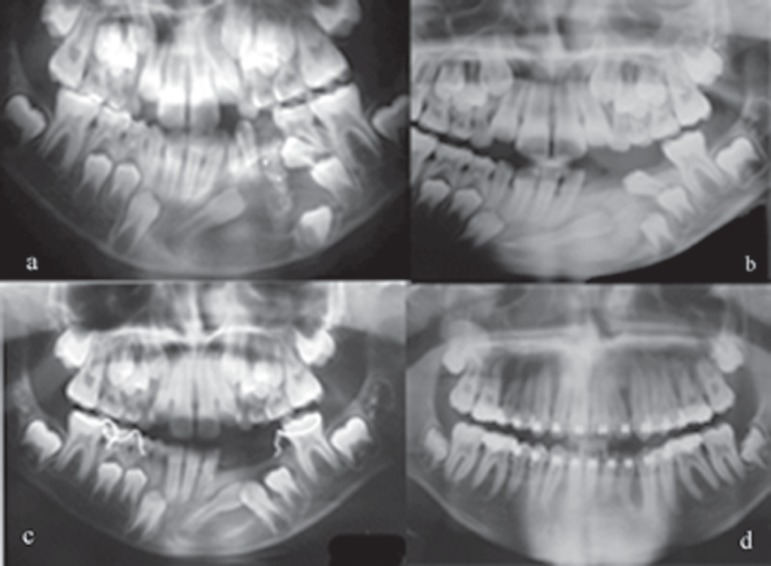

Figure 2.

Panel of panoramic radiographs. (a) Unilocular osteolytic cystic lesion with sclerotic border associated to lateral incisor. Canine and second premolar dislocated apically. Radiopacity of iodoform gauze can be seen. (b) Six-month followup radiographic image showing that teeth have erupted spontaneously. (c) One-year follow-up showing that teeth are still in eruption process. Image of space-maintainer installed can be seen. (d) Seven-year radiographic image showed complete osteogenesis and teeth eruption

Case 2

A 10-year-old girl was referred to the Oral Surgery Clinic for treatment of a cyst in the right side of the mandible found casually on a panoramic radiograph taken for orthodontic treatment planning. The patient came without complaint but oral examination revealed a slight swelling of alveolar mucosa related to a primary molar and canine. The panoramic radiograph showed a segmented radiolucent area in the right mandible body presenting a sclerotic border. Inclusion and dislocation of the permanent canine, first and second premolars was also associated (Figure 3a). After local bone aspiration and biopsy, a diagnosis of keratocystic odontogenic tumor was established. The cyst capsule fragment presented a stratified epithelial lining with prominent columnar basal cell layer and parakeratinized daughter microcysts were scattered in the connective tissue wall (Figure 4). In an attempt to maintain the permanent teeth, the patient was submitted to decompression procedure by extraction of the primary molars and insertion of iodoform gauze (Figure 3b). Changing of medication gauze and acrylic plug were performed as described for Case 1. The permanent teeth went to natural eruption and 2 years after the first visit lesion had healed (Figure 3c). Patient was submitted to orthodontic treatment and radiographic follow-up of 7 years showed no lesion recurrence (Figure 3d).

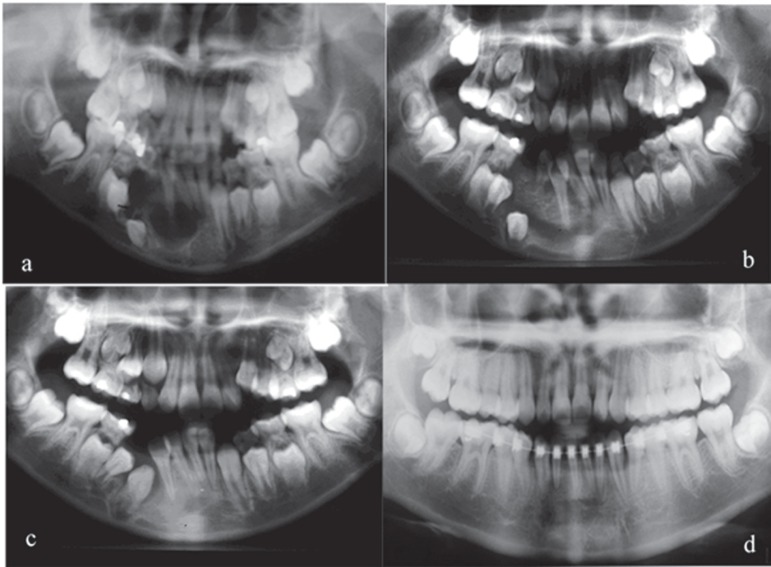

Figure 3.

Panel of panoramic radiographs. (a) Segmented osteolytic lesion in the right mandible body presenting a sclerotic border and inclusion and displacement of permanent canine, first and second premolars. (b) Three-month follow-up image showing that permanent teeth went to natural eruption and decompression was maintained by iodoform gauze. (c) Two-year follow-up image showing permanent teeth in spontaneous eruption. (d) Seven-year follow-up image showing complete osteogenesis and teeth eruption

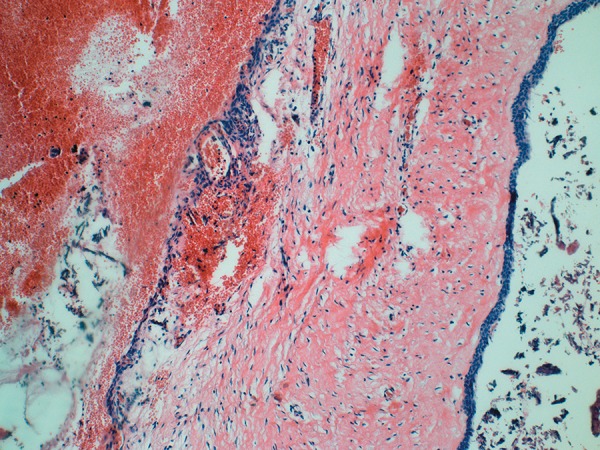

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of the lesion showing stratified epithelial lining with prominent columnar basal cell layer and parakeratin (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x400)

DISCUSSION

The histogenesis of dentigerous cyst remains unclear. Classically, they are defined as cysts of development of the dental follicle. Authors related them to traumatic pathology or inflammatory processes in primary teeth3,7,9,13.

On the other hand, KCOT, formerly known as OKC and classified as a neoplasm by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 200511, is a benign odontogenic tumor derived from the dental lamina that requires special surgical consideration because of its known aggressive behavior and high tendency to recur2. KCOTs have been suggested as one of the major diagnostic criteria of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS)5. The rate of recurrence varies enormously, from 0% to 62%2,12, and the majority of recurrences occur within the first 5 years after treatment8. Most surgeons support complete removal with extension margins or careful curettage of the surrounding tissues2,5,6,8,10,11,12,14.

Recurrence rates may be influenced by a variety of factors, including the length of the follow-up period, treatment modality, lesion size, histopathological presence of daughter cysts, and the number of cases investigated6,8.

Marsupialization or decompressions are rather advisable treatments primarily in dentigerous cysts when we wish to preserve the cyst-associated teeth and promote their eruption even though it is difficult to reliably predict the tooth eruption4,7,10. Regarding treatment of an KCOT, removal of the cyst including the associated tooth and surrounding bone has been generally performed6,14. Recently, it has been reported that marsupialization can be an effective alternative5,8,10,14. Some authors5,6,10 described the use of decompression and secondary enucleation as first line treatment option for KCOT. Furthermore when achieving a significant reduction of the lumen which can be confirmed trough radiographic imaging, a secondary cystectomy is justified to prevent recurrence of the lesion. The patients of this report were in the first decade of life and still had unerupted permanent teeth associated with the KCOTs. It was thus difficult to make a decision for an aggressive surgery over conservative management.

In both cases, clinical judgment led to the preservation of the permanent teeth considering the age of the patients, the development of tooth roots and the possibility of that conservative therapeutic could relieve pressure from cyst's fluid, allowing reduction of the intraosseous lesion and apposition of new bone to the cystic walls1,10.

Some clinical and molecular studies have shown that the parakeratinized and orthokeratinized KCOTs were significantly different in molecular area as well as the recurrence rate; orthokeratinized OKCs had a lower recurrence rate than the parakeratinized OKCs1,6,8. Although the OKC presented in this paper is of parakeratinized type and exhibited daughter cysts observed within the lesion wall, which is a known factor of aggressiveness in KCOTs, the lesion did not recur after 7 years of follow-up.

Marsupialization has been considered as effective as a preliminary treatment for large KCOTs and it seems not to affect the recurrence tendency of this type of cyst. It is important to notice that the decompression procedure here was done without the supplementary enucleation neither or application of Carnoy's solution.

Reports also describe probable changes in growth characteristics when KCOTs are submitted to decompression that turns it rather less aggressive1,6. Some authors have observed epithelial dedifferentiation and loss of cytokeratin-10 production after a mean treatment time of 9 months, but they also suggested that the longitudinal follow-up of patients will determine whether this change is associated with lower rates of recurrence1.

Sometimes after marsupialization/decompression eruption of the associated impacted teeth assumes an unusual position and orthodontic traction of the impacted tooth has to be performed if adequate space exists4. In both cases, teeth that were present came to eruption spontaneously and orthodontic treatment was necessary to assure better alignment of teeth in dental arch. The left mandibular lateral incisor on the dentigerous cyst case assumed a lingual position and orthodontic treatment was important to correct the direction of eruption.

Although complete resolution of the lesions was achieved by a conservative approach, preserving anatomy and function, we agree with other authors that long-term follow-up is mandatory and cannot be overlooked6,8,11 especially considering the odontogenic keratocystic tumor.

CONCLUSIONS

Both cases had similar radiographic aspects, both occurred in children, in the mandible body and were associated to the same group of unerupted permanent teeth. It is important to point out that only with an incisional biopsy and histological examination it is possible to accomplish a definitive diagnosis. The treatment choice should regard conservative managements with low morbidity particularly in young patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.August M, Faquin WC, Troulis MJ, Kaban LB. Dedifferentiation of odontogenic keratocyst epithelium after cyst decompression. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:678–683. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirapathomsakul D, Sastravaha P, Jansisyanont P. A review of odontogenic keratocysts and the behavior of recurrences. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freitas DQ, Tempest LM, Sicoli E, Lopes-Neto FC. Bilateral dentigerous cystsreview of the literature and report of an unusual case. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2006;35:464–468. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/26194891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyomoto M, Kawakami M, Inoue M, Kirita T. Clinical conditions for eruption of maxillary canines and mandibular premolars associated with dentigerous cysts. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyun HK, Hong SD, Kim JW. Recurrent keratocystic odontogenic tumor in the mandible: a case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:e7–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolokythas A, Fernandes RP, Pazoki A, Ord RA. Odontogenic keratocystto decompress or not to decompress? A comparative study of decompression and enucleation versus resection/ peripheral ostectomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:640–644. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.06.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozelj V, Sotosek B. Inflammatory dentigerous cysts of children treated by tooth extraction and decompression - report of four cases. Br Dent J. 1999;187:587–590. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800339a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurette PE, Jorge J, Moraes M. Conservative treatment protocol of odontogenic keratocysta preliminary study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naclério MG, Simões WA, Zindel Deboni MC, Chilvarquer I, Aparecida TA. Dentigerous cyst associated with an upper permanent central incisorcase report and literature review. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2002;26:187–192. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.26.2.un28142h66k50300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura N, Mitsuyasu T, Mitsuyasu Y, Taketomi T, Higuchi Y, Ohishi M. Marsupialization for odontogenic keratocystslong term follow-up analysis of the effects and changes in growth characteristics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:543–553. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.128022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philipsen HP. Keratocystic odontogenic tumours. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sindransky D, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours.Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 306–307. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shear M. The aggressive nature of the odontogenic keratocystis it a benign cystic neoplasm? Part 1. Clinical and early experimental evidence of aggressive behaviour. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shear M. Cyst of the oral regions. 3rd ed. Oxford: White; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao YF, Wei JX, Wang SP. Treatment of odontogenic keratocystsa follow-up of 255 Chinese patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:151–156. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.125694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]