Abstract

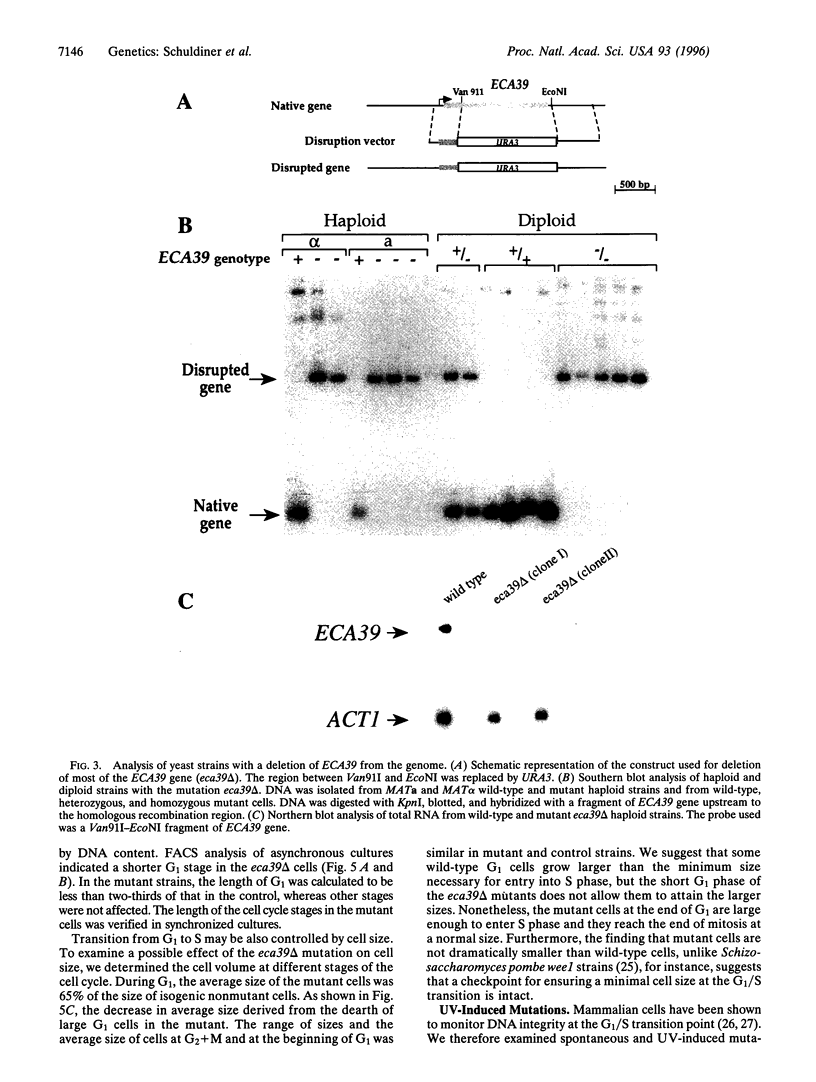

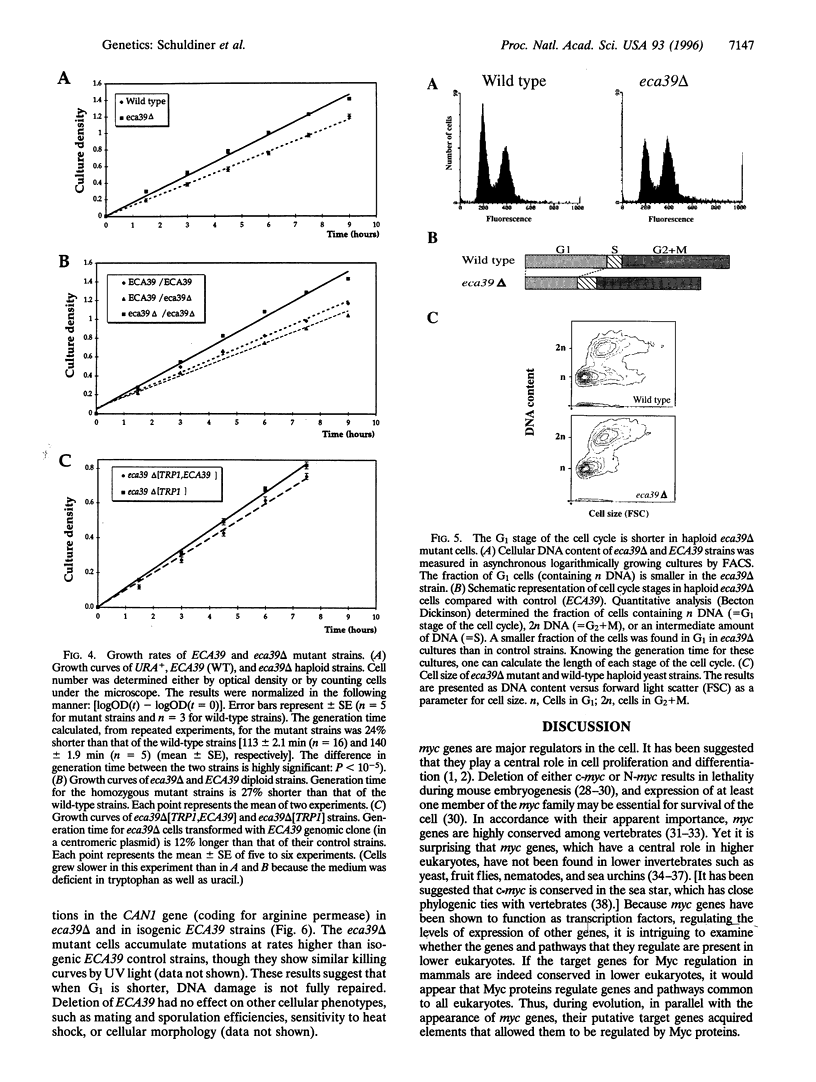

The c-myc oncogene has been shown to play a role in cell proliferation and apoptosis. The realization that myc oncogenes may control the level of expression of other genes has opened the field to search for genetic targets for Myc regulation. Recently, using a subtraction/coexpression strategy, a murine genetic target for Myc regulation, called EC439, was isolated. To further characterize the ECA39 gene, we set out to determine the evolutionary conservation of its regulatory and coding sequences. We describe the human, nematode, and budding yeast homologs of the mouse ECA39 gene. Identities between the mouse ECA39 protein and the human, nematode, or yeast proteins are 79%, 52%, and 49%, respectively. Interestingly, the recognition site for Myc binding, located 3' to the start site of transcription in the mouse gene, is also conserved in the human homolog. This regulatory element is missing in the ECA39 homologs from nematode or yeast, which also lack the regulator c-myc. To understand the function of ECA39, we deleted the gene from the yeast genome. Disruption of ECA39 which is a recessive mutation that leads to a marked alteration in the cell cycle. Mutant haploids and homozygous diploids have a faster growth rate than isogenic wild-type strains. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analyses indicate that the mutation shortens the G1 stage in the cell cycle. Moreover, mutant strains show higher rates of UV-induced mutations. The results suggest that the product of ECA39 is involved in the regulation of G1 to S transition.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amati B., Land H. Myc-Max-Mad: a transcription factor network controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994 Feb;4(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenisty N., Leder A., Kuo A., Leder P. An embryonically expressed gene is a target for c-Myc regulation via the c-Myc-binding sequence. Genes Dev. 1992 Dec;6(12B):2513–2523. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenisty N., Ornitz D. M., Bennett G. L., Sahagan B. G., Kuo A., Cardiff R. D., Leder P. Brain tumours and lymphomas in transgenic mice that carry HTLV-I LTR/c-myc and Ig/tax genes. Oncogene. 1992 Dec;7(12):2399–2405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard O., Cory S., Gerondakis S., Webb E., Adams J. M. Sequence of the murine and human cellular myc oncogenes and two modes of myc transcription resulting from chromosome translocation in B lymphoid tumours. EMBO J. 1983;2(12):2375–2383. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood E. M., Eisenman R. N. Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc. Science. 1991 Mar 8;251(4998):1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.2006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron J., Malynn B. A., Fisher P., Stewart V., Jeannotte L., Goff S. P., Robertson E. J., Alt F. W. Embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the N-myc gene. Genes Dev. 1992 Dec;6(12A):2248–2257. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson T. W., Sikorski R. S., Dante M., Shero J. H., Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992 Jan 2;110(1):119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. D. The myc oncogene: its role in transformation and differentiation. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:361–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. C., Wims M., Spotts G. D., Hann S. R., Bradley A. A null c-myc mutation causes lethality before 10.5 days of gestation in homozygotes and reduced fertility in heterozygous female mice. Genes Dev. 1993 Apr;7(4):671–682. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan G. I., Littlewood T. D. The role of c-myc in cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993 Feb;3(1):44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan G. I., Wyllie A. H., Gilbert C. S., Littlewood T. D., Land H., Brooks M., Waters C. M., Penn L. Z., Hancock D. C. Induction of apoptosis in fibroblasts by c-myc protein. Cell. 1992 Apr 3;69(1):119–128. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90123-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. P., Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983 Jul 1;132(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerring S. L., Spencer F., Hieter P. The CHL 1 (CTF 1) gene product of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is important for chromosome transmission and normal cell cycle progression in G2/M. EMBO J. 1990 Dec;9(13):4347–4358. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Kastan M. B. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994 Dec 16;266(5192):1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. Defects in a cell cycle checkpoint may be responsible for the genomic instability of cancer cells. Cell. 1992 Nov 13;71(4):543–546. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermeking H., Eick D. Mediation of c-Myc-induced apoptosis by p53. Science. 1994 Sep 30;265(5181):2091–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.8091232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter K. J., Eipel H. E. Microbial determinations by flow cytometry. J Gen Microbiol. 1979 Aug;113(2):369–375. doi: 10.1099/00221287-113-2-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M., Andrews S., Brinkman R., Cooper J., Ding H., Dover J., Du Z., Favello A., Fulton L., Gattung S. Complete nucleotide sequence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VIII. Science. 1994 Sep 30;265(5181):2077–2082. doi: 10.1126/science.8091229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K., Cochran B. H., Stiles C. D., Leder P. Cell-specific regulation of the c-myc gene by lymphocyte mitogens and platelet-derived growth factor. Cell. 1983 Dec;35(3 Pt 2):603–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K., Siebenlist U. The regulation and expression of c-myc in normal and malignant cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:317–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher B., Eisenman R. N. New light on Myc and Myb. Part I. Myc. Genes Dev. 1990 Dec;4(12A):2025–2035. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifflin D., Robinson J. J. Proto-oncogene homologous sequences in the sea urchin genome. Biosci Rep. 1988 Oct;8(5):415–419. doi: 10.1007/BF01121638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro J. M., Sikorski R., Reed S. I., Vogelstein B. Human p53 and CDC2Hs genes combine to inhibit the proliferation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Mar;12(3):1357–1365. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M. E., Levine A. J. Tumor-suppressor p53 and the cell cycle. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993 Feb;3(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronen D., Rotter V., Reisman D. Expression from the murine p53 promoter is mediated by factor binding to a downstream helix-loop-helix recognition motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 May 15;88(10):4128–4132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell P., Nurse P. Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog. Cell. 1987 May 22;49(4):559–567. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarid J., Leder P. Sequence analysis of a yeast genomic DNA fragment sharing homology with the human c-myc gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988 May 25;16(10):4725–4725. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.10.4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber-Agus N., Horner J., Torres R., Chiu F. C., DePinho R. A. Zebra fish myc family and max genes: differential expression and oncogenic activity throughout vertebrate evolution. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 May;13(5):2765–2775. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber-Agus N., Torres R., Horner J., Lau A., Jamrich M., DePinho R. A. Comparative analysis of the expression and oncogenic activities of Xenopus c-, N-, and L-myc homologs. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Apr;13(4):2456–2468. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo B. Z., Weinberg R. A. DNA sequences homologous to vertebrate oncogenes are conserved in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Nov;78(11):6789–6792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern E. M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975 Nov 5;98(3):503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer F., Hugerat Y., Simchen G., Hurko O., Connelly C., Hieter P. Yeast kar1 mutants provide an effective method for YAC transfer to new hosts. Genomics. 1994 Jul 1;22(1):118–126. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B. R., Perkins A. S., Tessarollo L., Sassoon D. A., Parada L. F. Loss of N-myc function results in embryonic lethality and failure of the epithelial component of the embryo to develop. Genes Dev. 1992 Dec;6(12A):2235–2247. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. S. Hybridization of denatured RNA and small DNA fragments transferred to nitrocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Sep;77(9):5201–5205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. W., Boom J. D., Marsh A. G. First non-vertebrate member of the myc gene family is seasonally expressed in an invertebrate testis. Oncogene. 1992 Oct;7(10):2007–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston R., Martin C., Craxton M., Huynh C., Coulson A., Hillier L., Durbin R., Green P., Shownkeen R., Halloran N. A survey of expressed genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet. 1992 May;1(2):114–123. doi: 10.1038/ng0592-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]