Abstract

Protein kinase C alpha (PKCα) can activate both pro- and anti-tumorigenic signaling depending upon cellular context. Here, we investigated the role of PKCα in lung tumorigenesis in vivo. Gene expression data sets revealed that primary human non-small lung cancers (NSCLC) express significantly decreased PKCα levels, indicating that loss of PKCα expression is a recurrent event in NSCLC. We evaluated the functional relevance of PKCα loss during lung tumorigenesis in three murine lung adenocarcinoma models (LSL-Kras, LA2-Kras and urethane exposure). Genetic deletion of PKCα resulted in a significant increase in lung tumor number, size, burden and grade, bypass of oncogene-induced senescence, progression from adenoma to carcinoma and a significant decrease in survival in vivo. The tumor promoting effect of PKCα loss was reflected in enhanced Kras-mediated expansion of bronchio-alveolar stem cells (BASCs), putative tumor-initiating cells, both in vitro and in vivo. LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibited a decrease in phospho-p38 MAPK in BASCs in vitro and in tumors in vivo, and treatment of LSL-Kras BASCs with a p38 inhibitor resulted in increased colony size indistinguishable from that observed in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. In addition, LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs exhibited a modest but reproducible increase in TGFβ1 mRNA, and addition of exogenous TGFβ1 to LSL-Kras BASCs results in enhanced growth similar to untreated BASCs from LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice. Conversely, a TGFβR1 inhibitor reversed the effects of PKCα loss in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/−BASCs. Finally, we identified the inhibitors of DNA binding (Id) Id1–3 and the Wilm’s Tumor 1 as potential downstream targets of PKCα-dependent tumor suppressor activity in vitro and in vivo. We conclude that PKCα suppresses tumor initiation and progression, at least in part, through a PKCα-p38MAPK-TGFβ signaling axis that regulates tumor cell proliferation and Kras-induced senescence. Our results provide the first direct evidence that PKCα exhibits tumor suppressor activity in the lung in vivo.

Keywords: tumor suppressor, lung adenocarcinoma, bronchio-alveolar stem cells, p38 MAPK, Wilm’s Tumor 1 gene, inhibitors of DNA Binding (Id)

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States with an estimated 160 340 deaths annually.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for ~85% of lung cancer diagnoses, exhibits a 5-year survival rate of only 16%,1 underscoring the importance of understanding both tumor promoting and tumor suppressive signaling pathways that drive NSCLC in order to identify potential therapeutic targets for better treatment strategies.

Protein kinase C (PKC) represents a family of ten structurallyrelated lipid-dependent serine/threonine kinases involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation and survival. The identification of PKC enzymes as intracellular receptors for the tumor promoting phorbol esters2,3 provided a suggestive causal link between PKCs and cellular transformation. However, the relationship between specific PKC isozymes and cancer is complex.4 Individual PKC isozymes exhibit cell type-specific expression patterns and complex signaling responses through different subcellular localization, substrate selection, and cofactor requirements. As a result, closely related PKC isozymes often have distinct, sometimes opposing roles in cancer.4 For example, PKC epsilon (PKCe) promotes cell proliferation and survival,5 and overexpression of PKCε increases anchorage-independent cell growth and tumorigenicity of NIH 3T3 cells.6 In contrast, the closely related isozyme, PKC delta (PKCδ), promotes apoptosis and inhibits NIH 3T3 cell growth.6 The opposing roles of PKCe and PKCd are also observed in vivo. Transgenic overexpression of PKCε in the epidermis promotes carcinogen-induced tumor formation, whereas overexpression of PKCd is protective.7,8

A similar dichotomy of function is seen in the two atypical PKC isozymes PKCι and PKCζ.9,10 We have shown that atypical PKCι is an oncogene in NSCLC.11 PKCι is overexpressed in primary human NSCLC tumors as a result of recurrent tumor-specific gene amplification, and PKCι is required for anchorage-independent growth and tumorigenesis of human NSCLC cells in vivo.11,12 Additionally, PKCι is required for Kras-mediated lung tumor initiation in the LSL-Kras model.13 PKCι also has a tumor promotive role in colon,14 ovarian,15,16 leukemia,17,18 pancreatic19,20 and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma21 cancers. Given the direct involvement of PKCι in tumorigenesis, we developed a novel therapeutic that selectively target oncogenic PKCι signaling,9,22,23 which is currently being evaluated in the clinic. In contrast, the highly related atypical PKCζ isozyme exhibits tumor suppressor activity in multiple tissues, including the ovary24 and lungs.25

PKC alpha (PKCα) is particularly interesting as it exhibits both tumor promoting and tumor suppressive activity depending upon cellular context. In hepatocellular carcinoma cells, PKCα knockdown reduces cell growth, migration and invasion, indicating a tumor promotive role.26 In contrast, activation of PKCα in LNCaP prostate cancer cells induces increased apoptosis suggesting a tumor suppressive activity.27 Likewise, genetic deletion of the PKCα gene Prkcα in APCmin/+ mice increased tumor size and reduced survival, supporting a tumor suppressive role in the colon.28 The role of PKCα in lung cancer is uncertain. On the one hand, selective activation of PKCα in NSCLC cells during S phase results in cellular senescence through G2/M cell cycle arrest,29 whereas inhibition of PKCα during G1 phase does not affect cell growth.30 Therefore, the question still remains whether PKCα is tumor promoting or tumor suppressive in the lung, and no studies have assessed the role of PKCα in lung tumorigenesis in vivo. To address this question, we assess the role of PKCα in three independent transgenic mouse models of Krαs-driven lung tumorigenesis. We observed a significant increase in tumor number, burden and grade as a result of PKCα loss. This effect is reflected in enhanced expansion of bronchio-alveolar stem cells (BASCs), tumor-initiating cells in these models, in the absence of PKCα. PKCα-mediated tumor suppression involves activation of a p38 MAPK-TGFβ signaling axis that induces cellular growth arrest in vitro, and enforces oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) in vivo.

RESULTS

PKCα expression is frequent decreased in human lung tumors

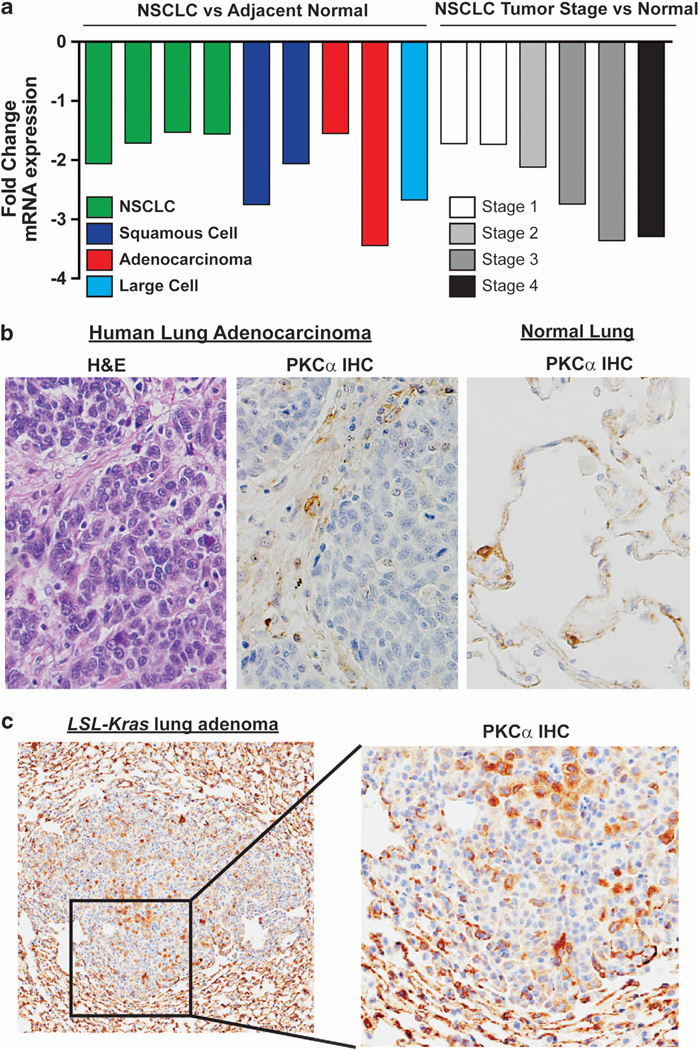

We first analyzed PKCα expression in human NSCLC gene expression data sets. The NextBio database revealed that PKCα is significantly downregulated in adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma, the three major NSCLC subtypes (Figure 1a). Interestingly, PKCα loss increased with tumor stage suggesting a role in tumor progression. Immunohistochemistry confirmed loss of PKCα in primary lung adenocarcinoma cells compared with the surrounding stroma (Figure 1b). Loss of PKCα was also observed in lung adenomas from LSL-Kras mice (Figure 1c). In LSL-Kras tumors, PKCα loss was greater in some areas of the tumor than others. These results are consistent with progressive PKCα loss with advanced tumor stage as LSL-Kras lung tumors are early stage adenomas. Thus, PKCα loss occurs in both primary human NSCLC tumors and LSL-Kras adenomas.

Figure 1.

Loss of PKCα is a frequent event in non-small cell lung cancer. (a) Analysis of publicly available gene expression data sets using NextBio revealed downregulation of PKCα in the three major forms of NSCLC (lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma), which is progressive with advanced tumor stage. (b) Immunohistochemical staining for PKCα in human lung adenocarcinoma and adjacent normal lung revealed loss of PKCα expression in tumor tissue. Photomicrograph is representative of three primary lung adenocarcinomas analyzed. (c) Loss of PKCα is observed in lung adenomas in LSL-Kras mice. Photomicrograph is representative of tumors from 15 tumor bearing LSL-Kras mice. A list of gene expression data sets analyzed in (a) can be found in Materials and Methods.

PKCα inhibits Kras-dependent tumor initiation

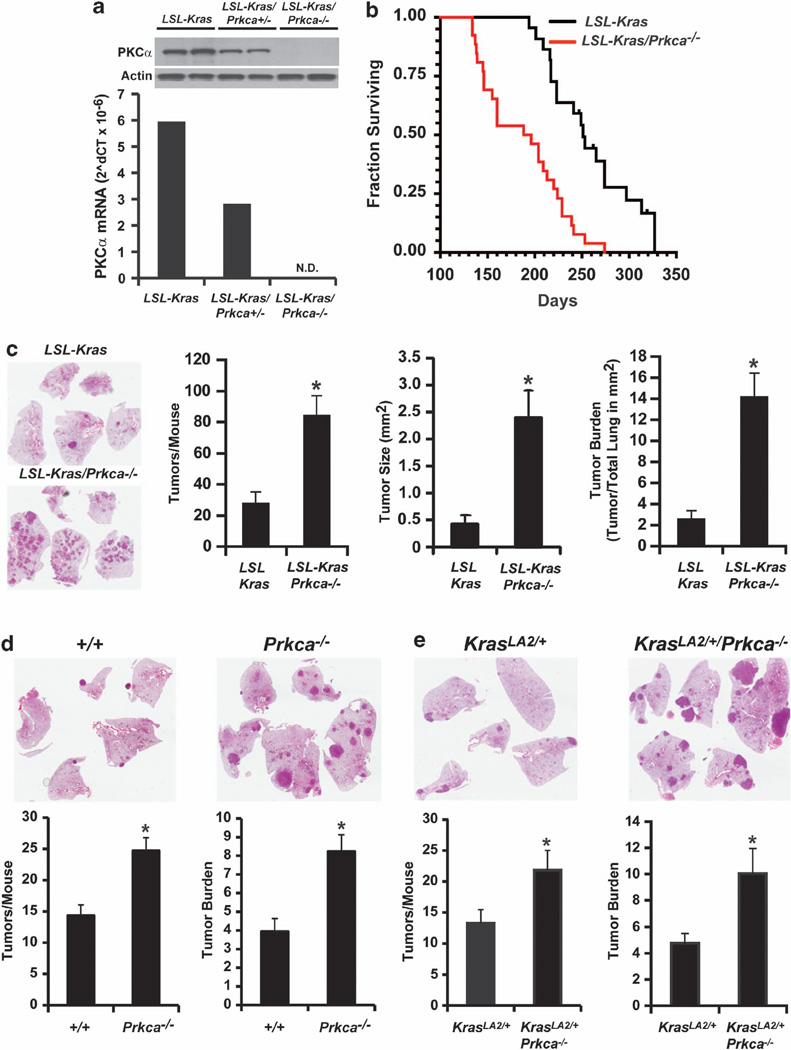

We next assessed the role of PKCα loss in Kras-mediated lung tumorigenesis using mice harboring constitutive deletion of Prkcα (Prkca−/− mice).59 Functional loss of PKCα was confirmed by quantitative PCR (Figure 2a) and immunoblot analysis (Figure 2a, inset) of lung tissue from non-transgenic (Ntg), heterozygous Prkca+/− and homozygous Prkca−/− mice. Homozygous Prkca−/− mice were crossed with LSL-Kras mice to generate bitransgenic LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice. Oncogenic Kras expression and lung tumorigenesis was initiated by intratracheal instillation of recombinant adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase as described previously.31 LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibited a significant decrease in median survival (196 days) compared with LSL-Kras mice (251 days; P<0.0001) (Figure 2b). Decreased survival correlated with a significant increase in tumor number, size and burden in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice (Figure 2c). To assess the generality of these results, we assessed tumor formation in Ntg or Prkca−/− mice after exposure to the lung carcinogen urethane (Figure 2d), and in KrasLA2/+ mice (Figure 2e), in which oncogenic Kras is spontaneously activated by homologous recombination.32 In both models, PKCα-deficiency resulted in a significant increase in tumor number and burden. Lung tumorigenesis was strictly dependent upon carcinogen exposure and/or oncogenic Kras activation as no tumors were observed in Ntg or Prkca−/− mice in the absence of tumor initiators (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Genetic loss of PKCα stimulates Kras-mediated lung tumorigenesis. (a) Lungs from LSL-Kras, LSL-Kras/Prkca+/− and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit progressive loss of PKCα mRNA. Data represent the mean mRNA values from two mice in each genotype Inset: Immunoblot analysis of lung extracts from these LSL-Kras, LSL-Kras/Prkca+/− and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice demonstrating loss of PKCα protein expression. Actin served as a loading control. (b) LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit decreased survival when compared with LSL-Kras after tumor induction. *P<0.001; N = 20/genotype. (c) Gross pathology of representative lungs from LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice demonstrate an enhanced tumorigenic phenotype associated with PKCα loss. Quantitative analysis of tumor number, tumor size and tumor burden demonstrate a statistically significant increase in these parameters in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice when compared with LSL-Kras mice. *P<0.001; N = 20 mice/genotype. (d) PKCα loss stimulates urethane-induced lung tumor number and burden; *P<0.001; N = 20 in each treatment group. (e) PKCα loss stimulates oncogenic KrasLA2-induced lung tumor number and burden. *P<0.03; N = 15.

Loss of PKCα induces tumor progression and bypass of OIS

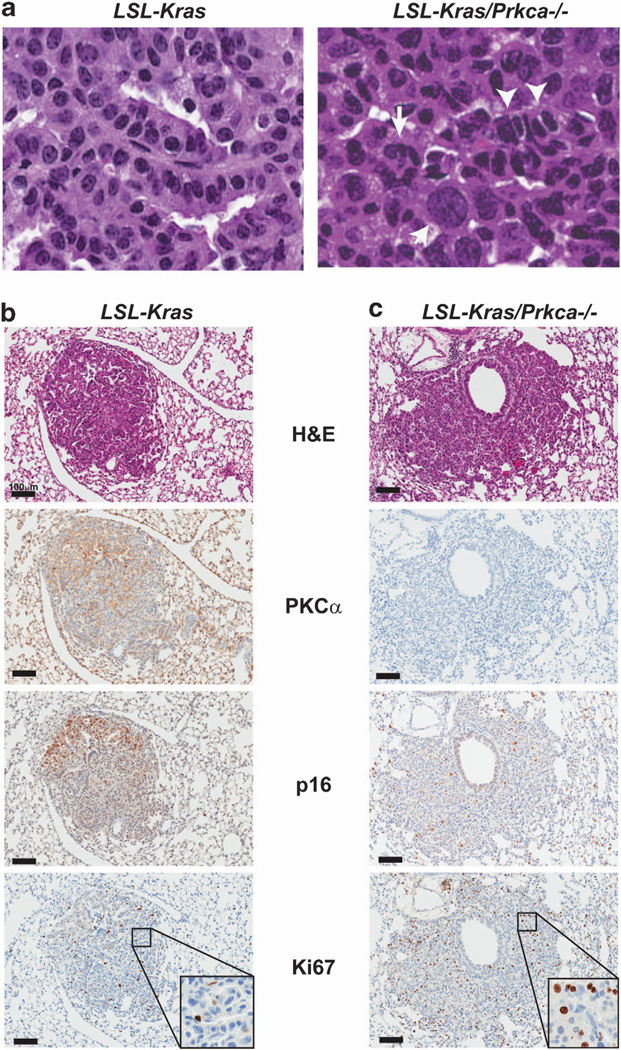

Pathological examination revealed a significant increase in tumor progression in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− tumors compared with LSL-Kras tumors. LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice tumors exhibited nuclear crowding, increased mitotic figures, nuclear swelling and highly variable nuclear morphologies (Figure 3a, right panel), all characteristics of progression from adenoma to carcinoma in this model.33 In contrast, most LSL-Kras tumors did not exhibit these characteristics, and were classified as adenomas (Figure 3a, left panel). Quantitative analysis revealed progression to carcinoma in all LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice (14/14) but in only 20% (3/15) of LSL-Kras mice (P = 0.00001; Fisher’s exact test). In LSL-Kras mice, progression to carcinoma is suppressed due to OIS in the presence of oncogenic Kras.34 OIS is characterized by widespread expression of the tumor suppressive cell cycle inhibitor p16Ink4A.35 As expected, LSL-Kras tumors exhibited widespread OIS as evidenced by positive staining for p16 and relatively low Ki67 staining (Figure 3c). Interestingly, LSL-Kras tumors exhibited regions that stained positive for both PKCα and p16, while other areas expressed low PKCα and p16 staining. In contrast, LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− tumors exhibited uniformly low p16 expression and increased Ki67 staining consistent with OIS bypass, increased tumor growth and tumor progression (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

PKCα loss leads to tumor progression and bypass of OIS in vivo. (a) Histological analysis of representative tumors from LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice demonstrating that tumors from LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit characteristic features of progression from adenoma to carcinoma, whereas most tumors from LSL-Kras mice are classified as adenomas. Arrow: large swollen nuclei with aberrant nuclear morphology; arrowheads: nuclear crowding and abnormal chromatin condensation. Immunohistochemical staining of tumors from LSL-Kras (b) and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− (c) mice for PKCα, p16 and Ki67. LSL-Kras tumors express abundant p16 in areas of the tumor where PKCα expression is retained, whereas tumors from LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice express no PKCα, little or no p16, and increased Ki67.

Loss of PKCα stimulates Kras-mediated BASC expansion

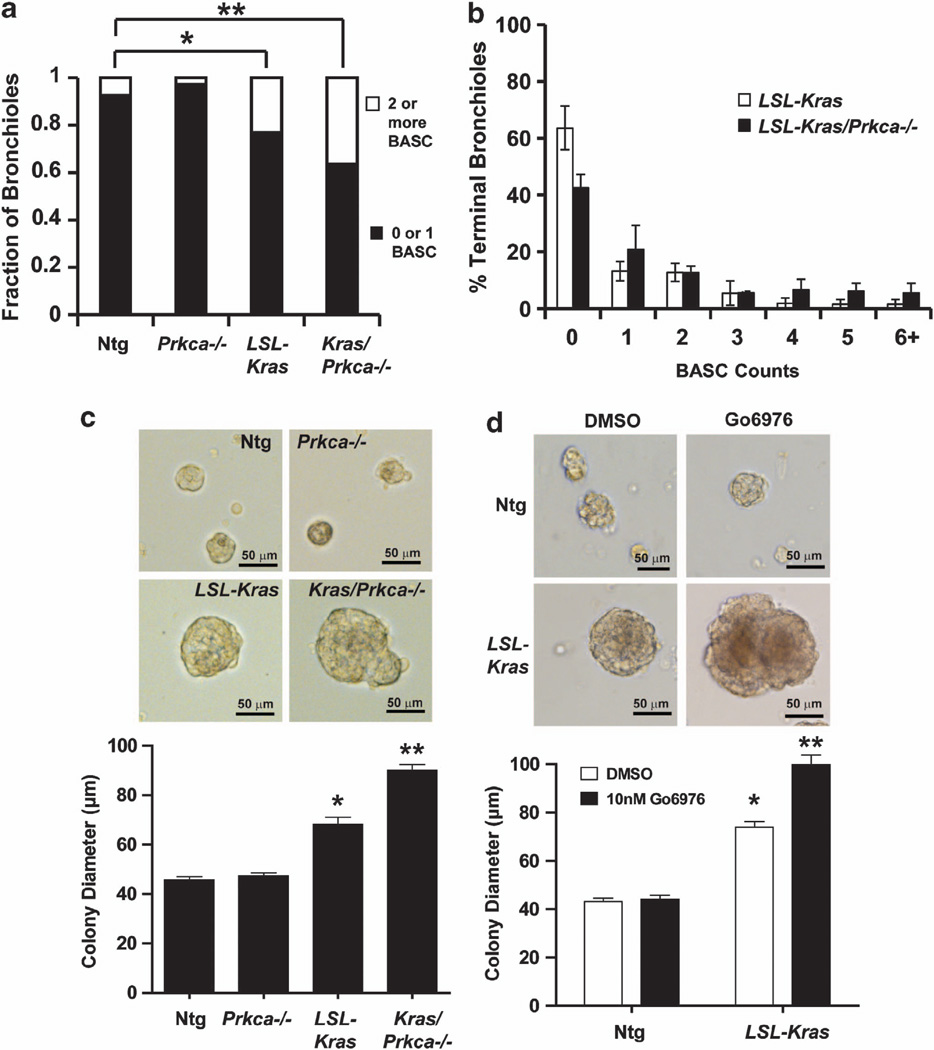

As PKCα inhibits initiation of Kras-driven lung tumors, we hypothesized that PKCα may inhibit expansion of BASCs, putative tumor-initiating cells in this model.36 Therefore, we quantitated BASCs within the terminal bronchioles (TB) of LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice in vivo as described previously.13,36 As expected, most TB from Ntg mice contained either no BASCs or a single BASC (Figure 4a). Interestingly, Prkca−/− mice exhibited no change in BASC number, indicating that PKCα is not a major factor regulating basal BASC number. In contrast, both LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibited a statistically significant increase in BASCs (more TB exhibiting two or more BASCs) when compared with Ntg mice. Analysis of BASC multiplicity demonstrated that LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit a significantly larger expansion of BASCs than LSL-Kras mice (more bronchioles of higher BASC multiplicity) (Figure 4b). To assess whether this difference is due to a direct effect of PKCα loss on BASCs, we assessed the growth of isolated BASC cultures ex vivo. BASCs isolated and purified from Ntg, Prkca−/−, LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice as described previously,36 were treated with adenoviral Cre to induce oncogenic Kras, and plated in three dimensional Matrigel culture as described previously.13 Quantitative analysis of BASC colonies grown ex vivo for 7 days demonstrate that loss of PKCα had little effect on BASC colony size in the absence of Kras, whereas oncogenic Kras expression resulted in a significant increase in BASC colony size, which was further enhanced by deletion of PKCα (Figure 4c). A similar increase in colony size was observed in BASCs from LSL-Kras mice treated with the selective PKCα/β inhibitor Gö6976 (Figure 4d) indicating that the effect of PKCα on the transformed growth of BASCs is dependent upon acute PKCα kinase activity. Thus, PKCα directly regulates BASC growth in the presence of oncogenic Kras.

Figure 4.

PKCα loss leads to expansion of Kras-transformed BASCs in vivo and enhanced BASC growth ex vivo. (a) Quantitative analysis of BASC number in vivo. TB were scored for BASCs as described in Materials and Methods and results plotted as the fraction of TB with either 0 or 1 BASCs or 2 or more BASCs. Both LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit an increase in BASC number when compared with Ntg or Prkca−/− mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.004. (b) BASC multiplicity analysis demonstrates that LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit a significantly larger increase in BASC expansion than LSL-Kras mice. P<0.04. (c) Morphology and quantitative analysis of colony diameter of BASCs from Ntg, Prkca−/−, LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice grown in three dimensional Matrigel culture for 7 days. *P<0.01 compared with Ntg; **P<0.0001 compared with LSL-Kras. (d) Effect of the selective PKCα inhibitor Go6976 on BASC colony growth. BASCs from Ntg and LSL-Kras mice were grown in three dimension culture in Matrigel in the presence of Go6976 (10 nM) or diluent (DMSO) for 7 days. Representative microphotographs and quantitative analysis of BASC colony size is shown. *P<0.0001 compared with Ntg; **P<0.0001 compared with LSL-Kras treated with DMSO.

p38 MAPK is a downstream effector of PKCα in Kras-induced tumorigenesis

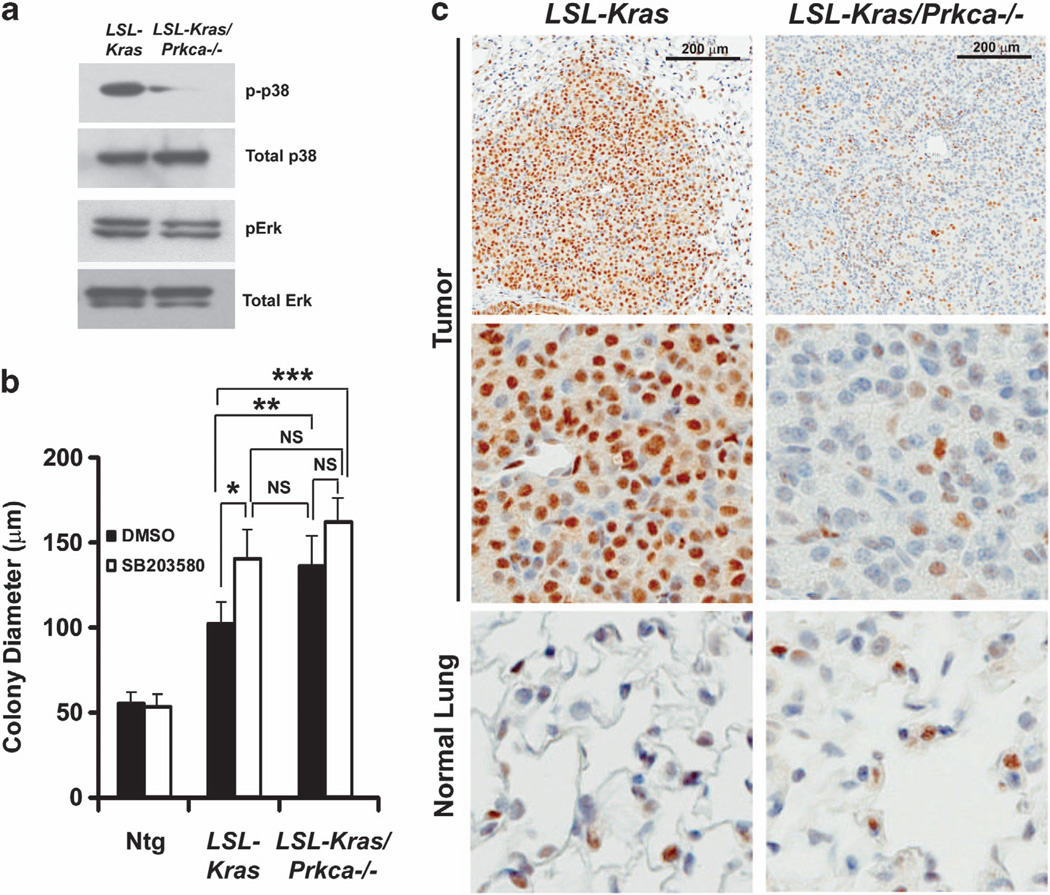

p38 MAPK has a key role in oncogenic Ras-induced senescence and p16Ink4A induction.37,38 p38 MAPK is phosphorylated and activated downstream of PKCα, and functions in the tumor promoting and suppressive effects of PKCα.26,27 Furthermore, the enhanced lung tumorigenesis observed in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice is similar to that seen in p38 MAPK-deficient mice on the LSL-Kras background.39 Therefore, we assessed whether p38 MAPK activation is modulated by PKCα in BASCs and LSL-Kras-induced lung tumors. Immunoblot analysis revealed decreased phospho-p38 MAPK in BASCs from LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice compared with LSL-Kras mice (Figure 5a). The effect of PKCα loss was selective for phospho-p38 MAPK as we observed little or no change in either total p38 MAPK, or total or phospho-Erk1/2 (Figure 5a). Addition of the selective p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 induced enhanced growth of BASCs from LSL-Kras mice, resulting in colonies comparable to those from LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice while having no effect on BASCs from Ntg or LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice (Figure 5b). Furthermore, LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− tumors exhibited reduced phospho-p38 MAPK staining compared with LSL-Kras tumors, indicating that p38 MAPK activity is regulated by PKCα in vivo (Figure 5c). Thus, p38 MAPK is selectively activated downstream of PKCα during LSL-Kras-induced lung tumorigenesis, and is likely involved in PKCα-mediated inhibition of tumor growth and progression.

Figure 5.

p38 MAPK is a downstream effector of PKCα in Kras-mediated BASC expansion. (a) Immunoblot analysis of total cell lysates of BASCs from LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice for phospho-p38 MAPK, total p38 MAPK, phospho-Erk 1,2 and total Erk 1,2. (b) Pharmacologic inhibition of p38 MAPK mimics PKCα loss on BASC colony growth. BASCs from Ntg, LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice were grown in three dimensional Matrigel culture in the presence of diluent (DMSO) or the p38 MAPK-selective inhibitor SB203580 (1 µm). SB203580 stimulates the growth of LSL-Kras BASCs while having no significant effect on Ntg or LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. *P<0.001; **P<0.02; ***P<0.003. (c) Immunohistochemical staining of tumors and normal adjacent lung from LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice for phospho-p38 MAPK. LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− tumors exhibit loss of phospho-p38 MAPK when compared with LSL-Kras tumors. Normal lung epithelium shows low phospho-p38 MAPK staining that is unaffected by genotype.

TGFβ1 mediates the effects of PKCα loss on BASC expansion

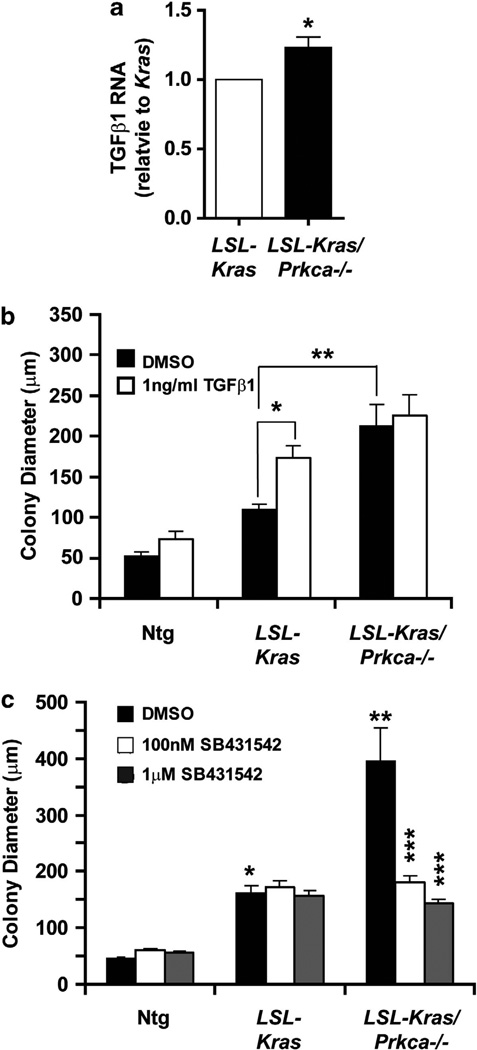

The TGFβ pathway is normally tumor suppressive, but in the presence of oncogenic Ras can become pro-oncogenic.40 Interestingly, TGFβ1 expression is elevated in p38 MAPK-deficient mice expressing oncogenic Kras,39 suggesting that a PKCα-p38 MAPK signaling axis may regulate lung tumorigenesis through TGFβ signaling. Consistent with this possibility, quantitative PCR analysis demonstrated a small but significant increase in TGFβ1 mRNA expression in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs compared with LSL-Kras BASCs (Figure 6a) and addition of exogenous TGFβ1 led to a significant increase in growth of LSL-Kras BASCs, while having no significant effect on Ntg or LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs (Figure 6b). In addition, treatment with the selective TGFβR1 inhibitor SB431542 blocked growth of LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs while having no significant effect on growth of Ntg or LSL-Kras BASCs (Figure 6c). Taken together, these data demonstrate that TGFβ signaling can mediate PKCα-regulated transformed growth, and indicate that PKCα inhibits lung tumor cell growth, at least in part, by suppressing TGFβ signaling.

Figure 6.

TGFβ1 is a critical mediator of the inhibitory effects of PKCα on BASC growth. (a) TGFβ1 expression is modestly but significantly induced in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs when compared with LSL-Kras BASCs. N = 4; *P<0.004. (b) TGFβ 1 mimics the effects of PKCα loss on BASC colony growth. Addition of exogenous TGFβ1 stimulates the growth of LSL-Kras BASC colonies while having no significant effect on Ntg or LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. *P<0.001; **P<0.001. All other comparisons were not significant. (c) The selective TGFβ receptor antagonist SB431542 inhibits the enhanced growth of LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs while having no significant effect on growth of Ntg or LSL-Kras BASCs. *P<0.001 compared with Ntg DMSO; **P<0.001 compared with LSL-Kras DMSO; ***P<0.001 compared with LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− DMSO. All other comparisons were not significant.

PKCα regulates expression of the inhibitors of DNA binding (Id) protein family

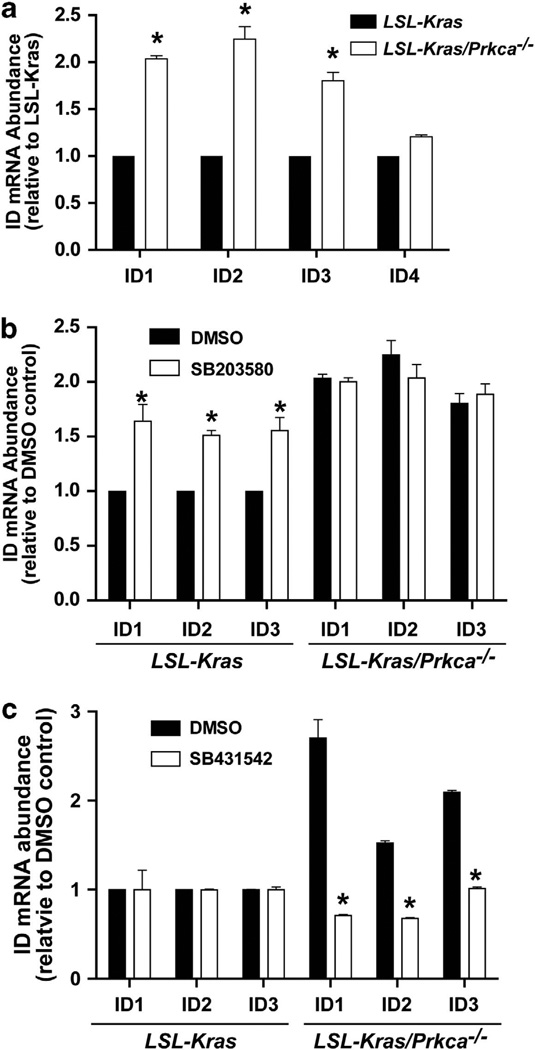

Our results in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice is consistent with the tumor suppressive effect of PKCα in the colon.41,42 In colon cancer, PKCα inhibits cell cycle by negatively regulating expression of the Id family of proteins, Id1–4.41,42 Indeed, LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs express significantly more Id1–3 but not Id4 compared with LSL-Kras BASCs (Figure 7a). PKCα-dependent Id gene expression requires p38 MAPK activity as Id1–3 mRNA is increased in LSL-Kras BASCs treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Figure 7b). Furthermore, Id1–3 expression was significantly decreased in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs treated with the TGFβR1 inhibitor SB431542 (Figure 7c). Thus, PKCα suppresses expression of Id family members through a p38 MAPK-TGFβ1 signaling pathway, suggesting that Id proteins may be central players in the PKCα-mediated regulation of lung tumor growth.

Figure 7.

PKCα loss induces p38 MAPK-, TGFβ-dependent expression of Inhibitor of DNA binding 1, 2 and 3 (Id1–3). (a) PKCα loss leads to induction of Id1, Id2 and Id3 mRNAs. Quantitative PCR for Id1–4 in LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. N = 3; *P<0.0001. (b) The p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 induces Id1–3 expression in LSL-Kras but not LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. N = 3; *P<0.01 compared with DMSO control. (c) The TGFβR1 inhibitor SB431542 reverses Id1–3 mRNA induction in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. N = 3; *P<0.001 compared with DMSO control.

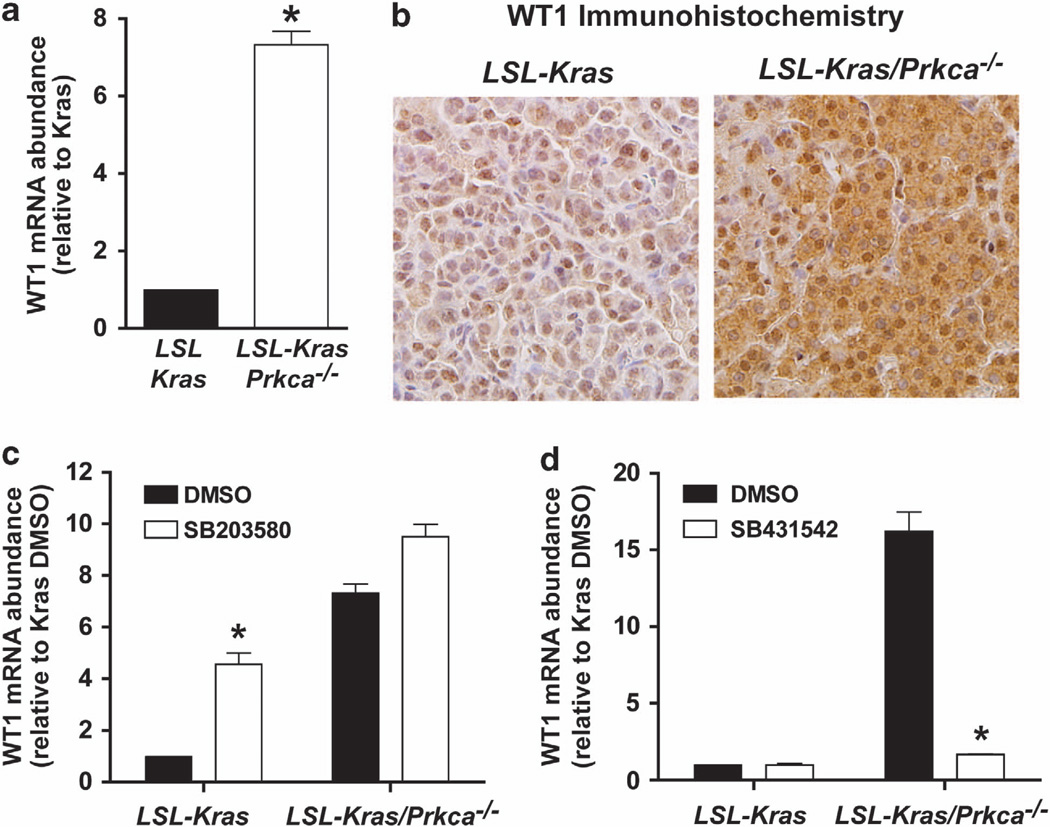

Deletion of PKCα induces Wilm’s Tumor 1 (WT1) during Kras-induced lung tumorigenesis

Our data demonstrate that loss of PKCα leads to bypass of OIS and tumor progression (Figure 3). This phenotype is strikingly similar to that seen in transgenic mice overexpressing the WT1 gene on the LSL-Kras background.43 LSL-Kras/Tg WT1 mice exhibit enhanced tumorigenesis and tumor progression as a result of OIS bypass.43 WT1 mRNA was elevated in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs compared with LSL-Kras BASCs (Figure 8b). Additionally, immunohistochemistry revealed that WT1 is elevated in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− compared with LSL-Kras tumors (Figure 8b), and treatment of LSL-Kras BASCs with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 led to induction of WT1 (Figure 8c). Finally, WT1 expression in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs was reduced after treatment with the TGFβR inhibitor SB431542 (Figure 8d). These data are consistent with a role for WT1 in facilitating OIS bypass downstream of PKCα loss in lung tumorigenesis.

Figure 8.

PKCα loss induces p38 MAPK- TGFβ-dependent expression of WT1. (a) WT1 mRNA is induced in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs when compared to LSL-Kras BASCs. N = 3; *P<0.0001. (b) Immunohistochemical staining for WT1. WT1 protein is elevated in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− tumors when compared with LSL-Kras tumors. (c) The p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 preferentially induces WT1 expression in LSL-Kras BASCs. N = 3; *P<0.001 compared with LSL-Kras DMSO. (d) The TGFβR1 inhibitor SB431542 preferentially inhibits WT1 expression in LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs. N = 3; *P<0.0001 compared with LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− DMSO.

DISCUSSION

PKC family members have been implicated in tumor promotion and suppression (for review see Fields and Murray4 and Fields and Gustafson44). There are conflicting reports regarding the role of PKCs in general, and PKCα specifically, in tumorigenesis and progression. These disparate results may be due to differences in cell- and tumor-type function, results obtained in cell lines in vitro versus in transgenic animal models in vivo, and the specificity of reagents used to identify PKCα function. Here we demonstrate that PKCα is a tumor suppressor in vivo using three models of Kras-mediated lung cancer. Genetic loss of PKCα in murine lung results in enhanced tumor growth and progression to carcinoma upon activation of oncogenic Kras. These results are consistent with the progressive loss of PKCα in primary human NSCLC tumors with advancing tumor stage. As PKCs are capable of phosphorylating Kras, leading to its association with mitochondrial BCL-XL and induction of cellular apoptosis,45 it will be of interest to assess whether such a mechanism also contributes to the tumor suppressor effects observed here. While our studies focused on Kras-mediated lung adenocarcinoma, human gene expression data indicate that PKCα is frequently lost in other major forms of NSCLC, including lung squamous cell carcinoma, which does not harbor frequent Kras mutations. Likewise, PKCα has a tumor suppressive role in APCmin intestinal tumorigenesis,28 indicating that the tumor suppressive role of PKCα extends beyond Kras-driven tumors. Whether the signaling mechanisms involved in PKCα-mediated tumor suppression differ depending upon oncogenic drivers is an important area for future investigation.

In addition to a role in tumor progression, our animal studies reveal an additional, unexpected role for PKCα in tumor initiation. LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice exhibit enhanced expansion of tumor-initiating BASCs, an effect that appears to be due, at least in part, to a direct effect of PKCα loss on the growth of Kras-transformed BASCs. As Prkca−/− mice harbor constitutive, organism-wide loss of PKCα, we cannot exclude an additional contribution of PKCα expressed in tumor-associated stroma and immune cells in tumor suppression in vivo. Such an analysis will require more complex animal models, in which PKCα expression can be conditionally controlled in a tissue- and time-specific manner.

Mechanistically, our data indicate that PKCα has a key role in enforcement of OIS in vivo. LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− tumors exhibit reduced p16Ink4A expression, an increase in Ki67 staining and progression to adenocarcinoma, consistent with OIS bypass. Interestingly, we observed regional coexpression of PKCα and p16Ink4A in LSL-Kras tumors, suggesting that PKCα loss during Kras-mediated tumorigenesis may represent an intrinsic mechanism by which these tumors overcome OIS. Our findings with PKCα loss bear a striking resemblance to those observed with genetic loss of p38 MAPK,39 suggesting a functional link between these genes. Indeed, our mechanistic studies reveal that p38 MAPK is a key downstream mediator of PKCα that regulates tumor initiation, at least in part, through control of Kras-mediated transformation of tumor-initiating BASCs. Our data are consistent with published reports demonstrating a key role of p38 MAPK in OIS37,38 and provide the first demonstration that a PKCα-p38 MAPK signaling axis has a role in OIS in Kras-mediated lung tumorigenesis in vivo. These results are also consistent with the finding that PKCα can regulate senescence in lung cancer cell lines in vitro.29

Our results provide compelling evidence for a PKCα-p38 MAPK-TGFβ signaling axis that drives the tumor suppressive effects of PKCα. Interestingly, genetic loss of PKCα in Kras-transformed BASCs resulted in a small but highly reproducible increase in TGFβ1 expression. This effect, though modest, is functionally relevant as exogenous TGFβ1 can mimic PKCα loss, and inhibition of TGFβ signaling reverses the effect of PKCα loss on BASC growth. Therefore, suppression of TGFβ signaling is a key mechanism by which PKCα inhibits lung cancer initiation and progression. Given the modest change in TGFβ1 mRNA abundance, PKCα likely also regulates other aspects of TGFβ signaling in the lung. In this regard, PKCα facilitates internalization of TGFβR from the cell surface in podocytes,46 and PKCα induces expression of both TGFβ1 and TGFβR1 in vascular smooth muscle cells.47 Our data suggest involvement of TGFβR1 in TGFβ signaling activation mediated by PKCα loss, as treatment with the TGFβR1/ALK5 selective inhibitor SB431542 inhibits the enhanced growth of LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− BASCs.

TGFβ, like PKCα, can be either tumor promoting or tumor suppressive depending on cellular context. The Id family of genes is negatively-regulated by PKCα in colon cancer41,42 where PKCα loss results in increased expression of Id1–4 which in turn regulate cyclin D1 and cell cycle progression.41 Consistent with these findings, we show that PKCα negatively regulates Id1–3 in BASCs. The effect of PKCα on Id expression requires the novel PKCα-p38 MAPK-TGFβ1 signaling axis characterized in this report. We hypothesize that PKCα functions as a tumor suppressor in lung, at least in part through inhibition of expression of Id genes, which in turn mediate PKCα-induced inhibition of BASC and lung tumor cell growth.

The effect of PKCα loss on Kras-induced lung tumorigenesis is reminiscent of the phenotype observed in WT1-overexpressing mice in the presence of oncogenic Kras.43 While WT1-overexpressing mice exhibit enhanced Kras-driven tumorigenesis, mice lacking WT1 exhibit enhanced OIS.43 PKCα loss leads to increased WT1 expression through a p38 MAPK-TGFβ-dependent pathway, consistent with the finding that WT1 expression is regulated by TGFβ signaling.48 Our data suggest that WT1 is a relevant downstream target involved in mediating OIS bypass in LSL-Kras/Prkca −/− mice. Analysis of gene expression data sets revealed a significant inverse relationship between PKCα and both WT1 and Id1 expression in primary human NSCLC tumors (P<0.02 for Id1; P<0.0002 for WT1), indicating the relevance of tumor PKCα loss in induction of WT1 and Id1 expression in primary human NSCLC.

Finally, our results have important implications for therapeutic intervention strategies targeting PKCα. The first isozyme-selective PKC inhibitor to enter clinical use was a 20-base antisense oligonucleotide targeting PKCα (LY900003/Aprinocarsen). Aprinocarsen inhibited PKCα expression and exhibited anti-tumor activity in nude mouse xenograft models.49,50 However, no clinical benefit was observed in phase II clinical trials of Aprinocarsen as a single agent in ovarian cancer51 or high-grade glioma.52 Likewise, a large phase III clinical trial of Aprinocarsen in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced NSCLC failed to demonstrate any survival benefit or difference in response.53 Therefore, despite encouraging preclinical data, PKCα has not been a successful target for cancer treatment. Our current study, and others cited herein, indicate that PKCα suppresses rather promotes tumorigenesis in the colon and the lung, calling into question the rationale for PKCα inhibitors in cancer therapy, at least in these tumor types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analysis of publicly available gene expression data sets

PKCα, WT1 and Id1 expression was assessed in publicly available gene expression data sets of human NSCLC tumors. All statistical analyses were completed using the ‘R Statistical Computing Language’.54 Microarray data sets for human NSCLC samples were normalized using the preprocess Core function of the R program package, and linear regression modeling was conducted to determine differentially expressed genes between groups.55 Correction for multiple testing was conducted and a false discovery rate of 0.05 was used as a cutoff. Human microarray data sets (accession id: GSE18842,56 GSE19188,57 GSE1987,58 GSE3398, GSE27556 and GSE2109) are available for download from the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Kras models of lung tumorigenesis

Three independent mouse models of Kras-mediated lung tumorigenesis were used to analyze the role of PKCα in lung cancer development and progression. In the first model, LSL-Kras mice (C57BL/6J)31 were mated with Prkca−/− mice (C57BL/6J:129/SV)59 to generate bitransgenic LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice. Tumorigenesis was initiated by installation of adenoviral Cre recombinase (final concentration 1.5 × 108 PFU/ml) intratracheally in two 50 µl doses into 6 to 8-week-old mice as described previously60 using Ntg, LSL-Kras and Prkca−/− littermates as controls. In the second model, KrasLA2 mice (C57BL/6J) were crossed to Prkca −/− mice to obtain KrasLA2/Prkca −/− mice. KrasLA2 mice develop lung tumors as a result of spontaneous recombination of the KrasLA2 allele and expression of oncogenic Kras as described previously.61 KrasLA2 and KrasLA2/Prkca−/− littermates were killed at 12 weeks of age and the lungs analyzed for tumor number and burden. In the third model, 6-week-old Ntg and Prkca−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally once a week for 6 weeks with 1 mg/kg urethane in 0.9% NaCl as previously described.62 The mice were killed 6 weeks after cessation of urethane exposure and the lungs harvested and assessed for tumor number and burden. All experiments used littermates from transgenic crosses as controls to control for possible strain differences. All animal experiments were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/− mice were sacrificed 12 weeks after adenoviral Cre instillation and lungs were formalin-fixed, embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned and stained with H&E for histology and immunohistochemical analysis as described previously.11,13,63 H&E-stained sections were imaged using Aperio ScanScope XT (Vista, CA, USA) and analyzed using Aperio ImageScope (v11.1.2.752) to determine tumor number, area, burden and pathological assessment of tumor staging. Sections were stained for PKCα (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; no. ab32376), p16 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA; sc-1207), Ki67 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), phospho-p38 MAPK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA; no. 9211) and WT1 (Santa Cruz sc-192) using antibodies diluted in PBS/Tween and visualized using Envision Plus Dual Labeled Polymer Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (DAKO).

BASCs were identified and quantitated in formalin-fixed mouse lung sections as described previously.13,64 The number of SPC-, CCSP-positive BASCs per TB was determined using Image-Pro Plus 6.3 and analyzed for statistical significance as described previously.13 The number of mice and TB analyzed in Figures 4b and c was as follows; Ntg: six mice/159 TB; LSL-Kras: four mice/92 TB, Prkca−/− /: four mice/116 TB and LSL-Kras/Prkca−/−: four mice/74 TB.

BASC isolation and ex vivo culture

BASCs were isolated as previously described.13 Isolated BASCs were resuspended in BEGM (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) media without hydrocortisone containing keratinocyte growth factor (10 ng/ml; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and 5% charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum and plated onto Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA)-coated tissue culture plates. Cells were incubated with adenoviral Cre (75 PFU/cell). p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (1 µm), PKC inhibitor Go6976 (10 nm), recombinant TGFβ1 (1ng/ml), or TGFβR inhibitor SB431542 (as indicated in the figure legends) were added to the media 24h after plating, and the media was changed every 2 days. Bright-field images were captured using an Olympus (Center Valley, PA, USA) IX71 microscope and colony size was determined after 7 days using Image-Pro Plus 6.3 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Quantitative PCR analysis

BASCs were released from Matrigel using BD cell recovery solution following the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Bioscience). Total RNA was isolated using RNAqueous (Ambion, Grand Island, NY, USA) and RNA quantity and quality assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. quantitative PCR was performed using reagents purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) to detect mouse PKCα, TGFβ1, Id1–4 and WT1 using an Applied Biosystems (Grand Island, NY, USA) ViiA7 PCR machine. Data were analyzed using ViiA 7 software and mRNA expression was normalized to 18S RNA.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the number and distribution of BASCs were assessed using the Cochrane-Armitage test using StatsDirect 2.6.1 (Cheshire, UK). The Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA statistical analyses were done using SigmaStat 3.5 (San Jose, CA, USA). A P-value of o0.05 was considered statistically significant. Animal survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Brandy Edenfield for immunohistochemical staining procedures, Capella Weems for technical assistance, Justin Weems and Dr Lee Jamieson for animal husbandry and members of the Fields laboratory for support, encouragement and critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA081436-16 to APF and R01 CA140290-03 to NRM). APF is the Monica Flynn Jacoby Endowed Professor of Cancer Research.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castagna M, Takai Y, Kaibuchi K, Sano K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Direct activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7847–7851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kikkawa U, Takai Y, Tanaka Y, Miyake R, Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C as a possible receptor protein of tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11442–11445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fields AP, Murray NR. Protein kinase C isozymes as therapeutic targets for treatment of human cancers. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2008;48:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacace AM, Ueffing M, Philipp A, Han EK, Kolch W, Weinstein IB. PKC epsilon functions as an oncogene by enhancing activation of the Raf kinase. Oncogene. 1996;13:2517–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mischak H, Goodnight JA, Kolch W, Martiny-Baron G, Schaechtle C, Kazanietz MG, et al. Overexpression of protein kinase C-delta and -epsilon in NIH 3T3 cells induces opposite effects on growth, morphology, anchorage dependence, and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6090–6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddig PJ, Dreckschmidt NE, Ahrens H, Simsiman R, Tseng CP, Zou J, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing protein kinase Cdelta in the epidermis are resistant to skin tumor promotion by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5710–5718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddig PJ, Dreckschmidt NE, Zou J, Bourguignon SE, Oberley TD, Verma AK. Transgenic mice overexpressing protein kinase C epsilon in their epidermis exhibit reduced papilloma burden but enhanced carcinoma formation after tumor promotion. Cancer Res. 2000;60:595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fields AP, Frederick LA, Regala RP. Targeting the oncogenic protein kinase Ciota signalling pathway for the treatment of cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 5):996–1000. doi: 10.1042/BST0350996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Justilien V, Fields A. Atypical PKCs as targets for cancer therapy. In: Kazanietz M, editor. Protein Kinase C in Cancer Signaling and Therapy. London: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regala RP, Weems C, Jamieson L, Khoor A, Edell ES, Lohse CM, et al. Atypical protein kinase C iota is an oncogene in human non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8905–8911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regala RP, Weems C, Jamieson L, Copland JA, Thompson EA, Fields AP. Atypical protein kinase Ciota plays a critical role in human lung cancer cell growth and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31109–31115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regala RP, Davis RK, Kunz A, Khoor A, Leitges M, Fields AP. Atypical protein kinase Ci is required for bronchioalveolar stem cell expansion and lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7603–7611. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray NR, Jamieson L, Yu W, Zhang J, Gokmen-Polar Y, Sier D, et al. Protein kinase Ciota is required for Ras transformation and colon carcinogenesis in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:797–802. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eder AM, Sui X, Rosen DG, Nolden LK, Cheng KW, Lahad JP, et al. Atypical PKCiota contributes to poor prognosis through loss of apical-basal polarity and cyclin E overexpression in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12519–12524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Huang J, Yang N, Liang S, Barchetti A, Giannakakis A, et al. Integrative genomic analysis of protein kinase C (PKC) family identifies PKCiota as a biomarker and potential oncogene in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4627–4635. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson L, Carpenter L, Biden TJ, Fields AP. Protein kinase Ciota activity is necessary for Bcr-Abl-mediated resistance to drug-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3927–3930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray NR, Fields AP. Atypical protein kinase Ciota protects human leukemia cells against drug-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27521–27524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scotti ML, Bamlet WR, Smyrk TC, Fields AP, Murray NR. Protein kinase Cι is required for pancreatic cancer cell transformed growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2064–2074. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scotti ML, Smith KE, Butler AM, Calcagno SR, Crawford HC, Leitges M, et al. Protein kinase Ciota regulates pancreatic acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kikuchi K, Soundararajan A, Zarzabal LA, Weems CR, Nelon LD, Hampton ST, et al. Protein kinase Ciota as a therapeutic target in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:286–295. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdogan E, Lamark T, Stallings-Mann M, Lee J, Pellecchia M, Thompson EA, et al. Aurothiomalate inhibits transformed growth by targeting the PB1 domain of protein kinase Ciota. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28450–28459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stallings-Mann M, Jamieson L, Regala RP, Weems C, Murray NR, Fields AP. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of protein kinase Ciota blocks transformed growth of non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1767–1774. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nazarenko I, Jenny M, Keil J, Gieseler C, Weisshaupt K, Sehouli J, et al. Atypical protein kinase C zeta exhibits a proapoptotic function in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:919–934. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galvez AS, Duran A, Linares JF, Pathrose P, Castilla EA, Abu-Baker S, et al. Protein kinase Czeta represses the interleukin-6 promoter and impairs tumorigenesis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:104–115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01294-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh YH, Wu TT, Huang CY, Hsieh YS, Hwang JM, Liu JY. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in protein kinase Calpha-regulated invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4320–4327. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka Y, Gavrielides MV, Mitsuuchi Y, Fujii T, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C promotes apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through activation of p38 MAPK and inhibition of the Akt survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33753–33762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oster H, Leitges M. Protein kinase C alpha but not PKCzeta suppresses intestinal tumor formation in ApcMin/+ mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6955–6963. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliva JL, Caino MC, Senderowicz AM, Kazanietz MG. S-phase-specific activation of PKCa induces senescence in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5466–5476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakagawa M, Oliva JL, Kothapalli D, Fournier A, Assoian RK, Kazanietz MG. Phorbol ester-induced G1 phase arrest selectively mediated by protein kinase Cdelta-dependent induction of p21. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33926–33934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Tuveson DA, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikitin AY, Alcaraz A, Anver MR, Bronson RT, Cardiff RD, Dixon D, et al. Classification of proliferative pulmonary lesions of the mouse: recommendations of the mouse models of human cancers consortium. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2307–2316. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nrc2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, et al. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121:823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwasa H, Han J, Ishikawa F. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 defines the common senescence-signalling pathway. Genes Cells. 2003;8:131–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W, Chen JX, Liao R, Deng Q, Zhou JJ, Huang S, et al. Sequential activation of the MEK-extracellular signal-regulated kinase and MKK3/6-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediates oncogenic ras-induced premature senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3389–3403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3389-3403.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ventura JJ, Tenbaum S, Perdiguero E, Huth M, Guerra C, Barbacid M, et al. p38alpha MAP kinase is essential in lung stem and progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2007;39:750–758. doi: 10.1038/ng2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grunert S, Jechlinger M, Beug H. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:657–665. doi: 10.1038/nrm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hao F, Pysz MA, Curry KJ, Haas KN, Seedhouse SJ, Black AR, et al. Protein kinase Calpha signaling regulates inhibitor of DNA binding 1 in the intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18104–18117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pysz MA, Leontieva OV, Bateman NW, Uronis JM, Curry KJ, Threadgill DW, et al. PKCα tumor suppression in the intestine is associated with transcriptional and translational inhibition of cyclin D1. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vicent S, Chen R, Sayles LC, Lin C, Walker RG, Gillespie AK, et al. Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) regulates KRAS-driven oncogenesis and senescence in mouse and human models. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3940–3952. doi: 10.1172/JCI44165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fields AP, Gustafson WC. Protein kinase C in disease: cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;233:519–537. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-397-6:519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bivona TG, Quatela SE, Bodemann BO, Ahearn IM, Soskis MJ, Mor A, et al. PKC regulates a farnesyl-electrostatic switch on K-Ras that promotes its association with Bcl-XL on mitochondria and induces apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2006;21:481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tossidou I, Starker G, Kruger J, Meier M, Leitges M, Haller H, et al. PKC-alpha modulates TGF-beta signaling and impairs podocyte survival. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24:627–634. doi: 10.1159/000257518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindschau C, Quass P, Menne J, Guler F, Fiebeler A, Leitges M, et al. Glucose-induced TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta receptor-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated by protein kinase C-alpha. Hypertension. 2003;42:335–341. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000087839.72582.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo X, Ding L, Xu J, Chegini N. Gene expression profiling of leiomyoma and myometrial smooth muscle cells in response to transforming growth factor-beta. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1097–1118. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dean N, McKay R, Miraglia L, Howard R, Cooper S, Giddings J, et al. Inhibition of growth of human tumor cell lines in nude mice by an antisense of oligonucleotide inhibitor of protein kinase C-alpha expression. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3499–3507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geiger T, Muller M, Dean NM, Fabbro D. Antitumor activity of a PKC-alpha anti-sense oligonucleotide in combination with standard chemotherapeutic agents against various human tumors transplanted into nude mice. Anticancer Drug Des. 1998;13:35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Advani R, Peethambaram P, Lum BL, Fisher GA, Hartmann L, Long HJ, et al. A phase II trial of aprinocarsen, an antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of protein kinase C alpha, administered as a 21-day infusion to patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:321–326. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grossman SA, Alavi JB, Supko JG, Carson KA, Priet R, Dorr FA, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of the antisense oligonucleotide aprinocarsen directed against protein kinase C-alpha delivered as a 21-day continuous intravenous infusion in patients with recurrent high-grade astrocytomas. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:32–40. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paz-Ares L, Douillard JY, Koralewski P, Manegold C, Smit EF, Reyes JM, et al. Phase III study of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without aprinocarsen, a protein kinase C-alpha antisense oligonucleotide, in patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1428–1434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dalgaard P. Introductory Statistics with R. 2nd edition, (ed) New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, W Huber, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanchez-Palencia A, Gomez-Morales M, Gomez-Capilla JA, Pedraza V, Boyero L, Rosell R, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals novel biomarkers in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:355–364. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hou J, Aerts J, den Hamer B, van Ijcken W, den Bakker M, Riegman P, et al. Gene expression-based classification of non-small cell lung carcinomas and survival prediction. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dehan E, Ben-Dor A, Liao W, Lipson D, Frimer H, Rienstein S, et al. Chromosomal aberrations and gene expression profiles in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;56:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leitges M, Plomann M, Standaert ML, Bandyopadhyay G, Sajan MP, Kanoh Y, et al. Knockout of PKC alpha enhances insulin signaling through PI3K. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:847–858. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.4.0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fasbender A, Lee JH, Walters RW, Moninger TO, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. Incorporation of adenovirus in calcium phosphate precipitates enhances gene transfer to airway epithelia in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:184–193. doi: 10.1172/JCI2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tuveson DA, Shaw AT, Willis NA, Silver DP, Jackson EL, Chang S, et al. Endogenous oncogenic K-ras(G12D) stimulates proliferation and widespread neoplastic and developmental defects. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:375–387. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malkinson AM, Nesbitt MN, Skamene E. Susceptibility to urethan-induced pulmonary adenomas between A/J and C57BL/6J mice: use of AXB and BXA recombinant inbred lines indicating a three-locus genetic model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:971–974. doi: 10.1093/jnci/75.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Regala R, Justilien V, Walsh MP, Weems C, Khoor A, Murray NR, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 promotes kras-mediated bronchio-alveolar stem cell expansion and lung cancer formation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Y, Iwanaga K, Raso MG, Wislez M, Hanna AE, Wieder ED, et al. Phosphati-dylinositol 3-kinase mediates bronchioalveolar stem cell expansion in mouse models of oncogenic K-ras-induced lung cancer. One. 2008;3:e2220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]