Eukaryotic initiation factor one (eIF1) is thought to promote an open conformation of the small ribosomal subunit so that it can identify correct initiation codons. This article poses a genetic strategy to identify mutations in eIF1 that suppress inappropriate initiation of UUG codons. Several eIF1 suppressor mutations increase its affinity for the 40S subunit, resulting in increased initiation accuracy in the cell.

Keywords: translation, initiation, eIF1, eIF2, ribosome, AUG recognition

Abstract

In the current model of translation initiation by the scanning mechanism, eIF1 promotes an open conformation of the 40S subunit competent for rapidly loading the eIF2·GTP·Met-tRNAi ternary complex (TC) in a metastable conformation (POUT) capable of sampling triplets entering the P site while blocking accommodation of Met-tRNAi in the PIN state and preventing completion of GTP hydrolysis (Pi release) by the TC. All of these functions should be reversed by eIF1 dissociation from the preinitiation complex (PIC) on AUG recognition. We tested this model by selecting eIF1 Ssu− mutations that suppress the elevated UUG initiation and reduced rate of TC loading in vivo conferred by an eIF1 (Sui−) substitution that eliminates a direct contact of eIF1 with the 40S subunit. Importantly, several Ssu− substitutions increase eIF1 affinity for 40S subunits in vitro, and the strongest-binding variant (D61G), predicted to eliminate ionic repulsion with 18S rRNA, both reduces the rate of eIF1 dissociation and destabilizes the PIN state of TC binding in reconstituted PICs harboring Sui− variants of eIF5 or eIF2. These findings establish that eIF1 dissociation from the 40S subunit is required for the PIN mode of TC binding and AUG recognition and that increasing eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit increases initiation accuracy in vivo. Our results further demonstrate that the GTPase-activating protein eIF5 and β-subunit of eIF2 promote accuracy by controlling eIF1 dissociation and the stability of TC binding to the PIC, beyond their roles in regulating GTP hydrolysis by eIF2.

INTRODUCTION

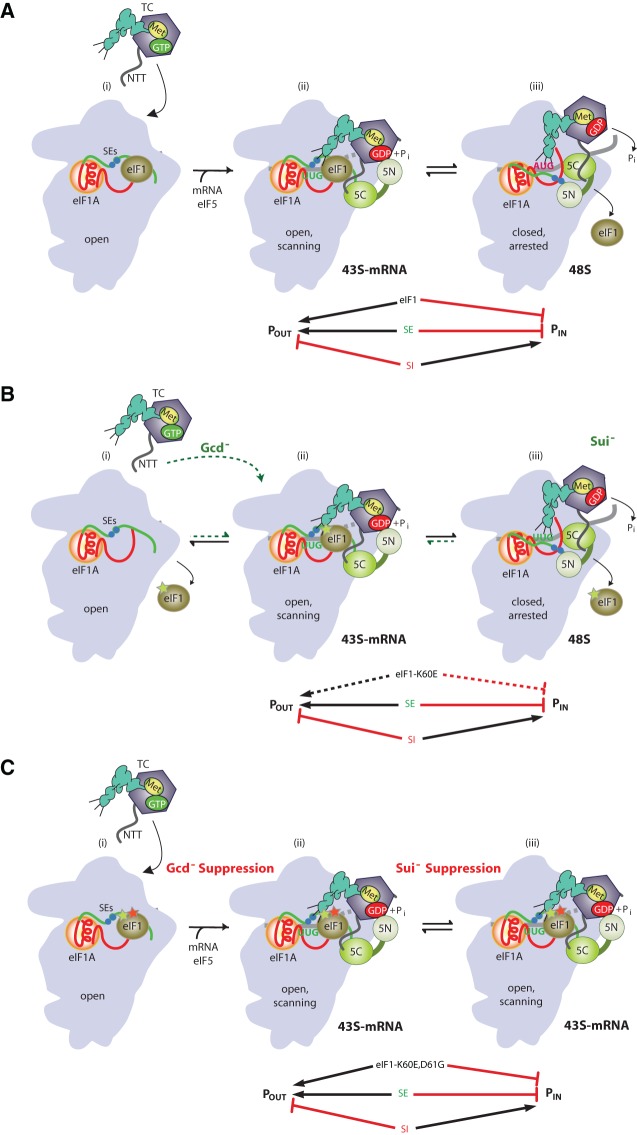

In translation initiation by the scanning mechanism, the small (40S) subunit harboring initiator methionyl tRNA (Met-tRNAi) bound to eIF2-GTP in a ternary complex (TC) attaches near the capped 5′ end of the mRNA and scans the leader base-by-base for an AUG triplet present in an optimal sequence context. According to our current model, eIF1 and eIF1A promote an “open” conformation of the 40S subunit that is competent for binding the TC in a metastable state (POUT) that allows the Met-tRNAi to sample successive triplets entering the P site for complementarity to the anticodon triplet. The GTPase-activating protein (GAP) eIF5 stimulates GTP hydrolysis by the TC, but completion of the reaction with release of Pi is blocked by the presence of eIF1 in the scanning preinitiation complex (PIC). Base-pairing of Met-tRNAi with an AUG triplet evokes a rearrangement of factors in the PIC, including displacement of eIF1 and the C-terminal tail (CTT) of eIF1A from the P site, and movement of the eIF1A CTT toward the GAP domain of eIF5. These rearrangements enable dissociation of eIF1 from the 40S subunit, evoking a closed, scanning-arrested conformation of the 40S subunit, Pi release from eIF2-GDP, and tighter binding of Met-tRNAi in the P site (PIN state). Thus, eIF1 performs a dual function in the scanning mechanism of promoting rapid TC loading in the POUT configuration while impeding rearrangement to the more stable PIN state until an AUG codon is recognized by Met-tRNAi (Fig. 1A; Hinnebusch 2011; Nanda et al. 2013).

FIGURE 1.

Model describing conformational rearrangements of the PIC during scanning and start codon recognition and the consequences of Sui− and Ssu− substitutions in eIF1. (A) Assembly of the PIC, scanning and start codon selection in WT cells. (i) eIF1 and the scanning enhancer (SEs) elements in the CTT of eIF1A stabilize an open conformation of the 40S subunit to which the TC rapidly loads. (ii) The 43S PIC in the open conformation scans the mRNA for the start codon with Met-tRNAi bound in the POUT state. The GAP domain in the N-terminal domain of eIF5 (5N) stimulates GTP hydrolysis by the TC to produce GDP•Pi, but release of Pi is blocked. The unstructured NTT of eIF2β interacts with eIF1 to stabilize eIF1•40S association and the open conformation. (iii) On AUG recognition, the Met-tRNAi moves from the POUT to PIN state, clashing with eIF1. Movement of eIF1 away from the P site disrupts its interaction with the eIF2β-NTT, and the latter interacts with the eIF5-CTD instead. eIF1 dissociates from the 40S subunit, and the eIF1A SE elements move away from the P site. The eIF5-NTD dissociates from eIF2 and interacts with the 40S subunit and the eIF1A CTT, facilitating Pi release and blocking reassociation of eIF1 with the 40S subunit. (Below) The arrows summarize that eIF1 and the eIF1A SE elements promote POUT and block the transition to the PIN state, whereas the scanning inhibitor (SI) element in the NTT of eIF1A stabilizes the PIN state. (Adapted from Hinnebusch and Lorsch 2012; Nanda et al. 2013.) (B) An eIF1 substitution (K60E in helix α1) that weakens its binding to the 40S subunit destabilizes the open/POUT conformation, reducing the rate of TC loading and increasing selection of near-cognate (UUG) start codons. (i) Aberrant dissociation of eIF1-K60E from the 40S subunit reduces the prevalence of the open/POUT conformation, decreasing the rate of TC loading and conferring the Gcd− phenotype. (ii,iii) Once TC eventually binds to the PIC and scanning commences, an increased frequency of eIF1-K60E dissociation from the open/POUT conformation also enables more frequent rearrangement to the PIN state at UUG codons, conferring the Sui− phenotype. (C) An eIF1 substitution (D61G in helix α1) that strengthens its binding to the 40S subunit destabilizes the closed/PIN state to mitigate the effects of eIF1-K60E, accelerating TC loading and suppressing selection of UUG start codons. By stabilizing 40S binding by eIF1-K60E, the D61G substitution increases the prevalence of the open/POUT conformation, rescuing rapid TC loading to diminish the Gcd− phenotype and reducing rearrangement to the PIN state at UUG codons to suppress the Sui− phenotype conferred by K60E.

The crystal structure of the 40S•eIF1 complex from Tetrahymena reveals direct contacts between 18S rRNA residues and basic residues in helix α1 and the β-hairpin (loop-1) of eIF1. The loop-1 residues were predicted to clash with the anticodon stem–loop (ASL) of tRNAi, with the latter bound to the P site in its canonical location (Rabl et al. 2011). Moreover, comparison of recent crystal structures of mammalian 40S•eIF1, 40S•eIF1•eIF1A, and 40S•eIF1A• mRNA•tRNAi complexes provides evidence for reorientation of Met-tRNAi from a position tilted toward the E site (likened to POUT) in complexes containing eIF1 to a state closer to the canonical P-site location (analogous to PIN), where it would clash with eIF1 and presumably help to provoke eIF1 dissociation from the PIC (Lomakin and Steitz 2013). By the same token, the contacts made by eIF1 loop-1 residues with 18S rRNA are expected to impede rearrangement from the POUT to PIN states of the bound TC for start codon recognition in addition to promoting stable eIF1 association with the scanning PIC.

Supporting this last prediction, we demonstrated recently that substituting basic residues of eIF1 located in α1 or loop-1 impairs eIF1 binding to 40S subunits in vitro and confers Gcd− and Sui− phenotypes in yeast cells that signify, respectively, a reduced rate of TC loading to the open conformation in the POUT state and inappropriate rearrangement to the closed conformation with TC bound in the PIN state at near-cognate (UUG) codons (Martin-Marcos et al. 2013). The reduced rate of TC binding to a 43S•mRNA complex overcomes the translational repression of GCN4 mRNA by its four upstream open reading frames (uORFs) and constitutively derepresses GCN4 expression, which normally occurs only under starvation or stress conditions that evoke eIF2α phosphorylation by Gcn2 and attendant reduction in TC formation (Hinnebusch 2005). This Gcd− phenotype of α1 or loop-1 substitutions was attributed to reduced eIF1 binding to the 40S subunit and attendant destabilization of the open PIC conformation to which TC rapidly binds, because it was suppressed by overexpressing the eIF1 mutant proteins. The increased UUG initiation (Sui−) phenotype of the eIF1 mutants was also suppressed by their overexpression, indicating that the weaker eIF1 binding to 40S subunits increases the probability of eIF1 release and rearrangement to the closed state at near-cognate codons (Martin-Marcos et al. 2013).

Interestingly, Gcd− and Sui− phenotypes are also conferred by mutations in the scanning enhancer (SE) elements in the eIF1A CTT. In accordance with their Gcd− phenotype, these SE substitutions destabilize the open conformation of the 40S subunit and reduce the rate of TC binding to 43S•mRNA complexes in vitro (Saini et al. 2010)—the same consequences evoked by the absence of eIF1 in the PIC (Passmore et al. 2007). As the Sui− phenotype of the eIF1A SE mutants is suppressed by overexpressing WT eIF1, it also seems to result from inappropriate dissociation of eIF1 at UUG codons. Hence the eIF1A SE elements function with eIF1 to promote the open conformation and POUT state of TC binding in the scanning complex while blocking the closed conformation and PIN state at non-AUGs (Fig. 1A). The latter activity can be rationalized by the prediction that the eIF1A CTT traverses the P site in the 43S PIC and would clash with the tRNAi ASL in its canonical P-site location (Yu et al. 2009). Hence, displacing the eIF1A CTT from the P site and its movement toward the eIF5 GAP domain on AUG recognition should remove an impediment to the PIN state in addition to triggering Pi release from eIF2-GDP (Nanda et al. 2013). (For convenience, we refer below to the open/POUT and closed/PIN states without implying that they are synonymous, as they refer to open or closed conformations of the 40S subunit and distinct locations of bound TC. Moreover, we do not stipulate whether the open and closed conformations are limited to the P site [Lomakin and Steitz 2013] or extend to the mRNA binding cleft [Passmore et al. 2007].)

In this report, we set out to test a key prediction of our model for the scanning mechanism, i.e., that mutations in eIF1 that strengthen its interaction with the 40S subunit would impede eIF1 dissociation from the scanning complex at near-cognate codons and increase the accuracy of initiation in vivo. It is also possible that hyperaccuracy mutations could be identified that impede an unknown function of eIF1 that promotes rearrangement from POUT to PIN prior to its release from the 40S subunit, in which case they would not necessarily alter eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit in vitro. Hyperaccuracy mutations in the first class would be expected to suppress the elevated UUG initiation (Sui−) phenotypes conferred by eIF1 substitutions in helix α1 or loop-1 described above that eliminate a direct contact between eIF1 and the 40S subunit. These Ssu− (suppressor of Sui−) mutations should also diminish the Gcd− phenotypes of the eIF1 Sui− mutants by restoring the open conformation of the PIC to which TC more rapidly binds (Saini et al. 2010).

We previously identified a panel of Ssu− substitutions in eIF1 by their ability to suppress the recessive lethality of the SUI5 mutation in eIF5 (G31R), which confers a dominant Sui− phenotype in cells also expressing WT eIF5. The eIF1 mutations also mitigated the elevated UUG initiation provoked by SUI5 and by the dominant Sui− substitution in eIF2β (S264Y) conferred by the SUI3-2 mutation (summarized in Fig. 2C; Martin-Marcos et al. 2011). There is currently no biochemical evidence that either SUI5 or SUI3-2 confers Sui− phenotypes by reducing eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit. Indeed, it was reported previously that both mutations accelerate GTP hydrolysis by the TC as the means of elevating UUG initiation (Huang et al. 1997). It was also shown that SUI5 stabilizes the closed conformation of the PIC specifically at UUG codons (Maag et al. 2006), but it is unclear whether this effect is provoked by a weaker eIF1–40S interaction. Nevertheless, we decided to test the previously isolated eIF1 Ssu− mutations for the ability to suppress the Sui− and Gcd− phenotypes of an eIF1 mutation in helix α1 (K60E) that eliminate a key contact with 18S rRNA, as well as for their effects on eIF1 binding to purified 40S subunits in vitro.

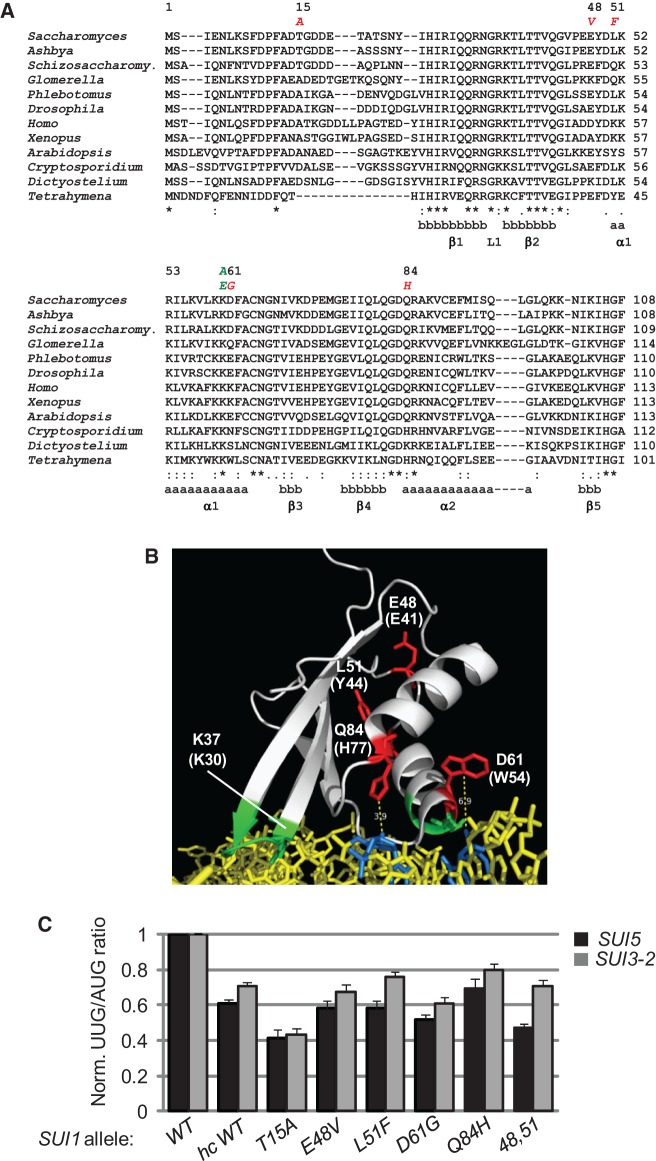

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the locations and phenotypes of Ssu− substitutions of yeast eIF1. (A) Alignment of eIF1 sequences from diverse eukaryotes. Secondary structures are indicated as α-helix (a) or β-sheet (b). Residues substituted by site-directed mutagenesis are indicated above, with green designating Sui− and red indicating Ssu− phenotypes. (B) Ribbon depiction of Tetrahymena thermophila eIF1 bound to the 40S subunit (PDB file 2XZM). The 18S rRNA phosphate backbone is shown in yellow, with bases predicted to contact eIF1 residues in blue. Highlighted residues correspond to those in yeast eIF1 that can be substituted to confer Sui− (in green) or Ssu− (in red) phenotypes. The corresponding residues in Tetrahymena eIF1 are indicated in parentheses. (C) eIF1 Ssu− substitutions reduce the HIS4 UUG:AUG initiation ratio in SUI5 and SUI3-2 cells. These data were published previously (Martin-Marcos et al. 2011) and are presented here in a different format for ease of comparison. For the SUI5 results (black bars), whole-cell extracts (WCEs) prepared from derivatives of sui1Δ his4-301-myc SUI5 and sui1Δ HIS4-myc SUI5 yeast strains harboring the indicated SUI1 alleles were subjected to Western analysis with antibodies against myc epitope or Gcd6 (examined as a loading control). Western signals were quantified, and the mean ratios of his4-301-myc to His4-myc abundance (each normalized to Gcd6 abundance) were normalized to the corresponding values measured for the WT SUI1 strain and plotted; error bars, SEMs. In cells containing WT eIF1, SUI5 increases the his4-301-myc:His4-myc ratio by a factor of approximately five. For the SUI3-2 results (gray bars), β-galactosidase activities expressed from matched HIS4-lacZ reporters with AUG or UUG start codon were measured in WCEs of derivatives of a sui1Δ his4-301 SUI3-2 strain harboring the indicated SUI1 alleles. The ratio of expression of the UUG to AUG reporter was calculated for replicate experiments, and the mean ratios were normalized to the corresponding values measured for the WT SUI1 strain and plotted; error bars, SEMs. In cells containing WT eIF1, SUI3-2 increases the HIS4-lacZ UUG:AUG ratio by a factor of approximately four.

We discovered that the eIF1 Ssu− mutations we identified previously cosuppress the Sui−and Gcd− phenotypes conferred by eIF1-K60E. They also cosuppress the Sui−/Gcd− phenotypes produced by SE mutations in the eIF1A CTT. These in vivo findings support the notion that the Ssu− mutations strengthen eIF1 contacts with the PIC or shift the equilibrium in favor of the open/POUT conformation to which eIF1 is most tightly bound. In agreement with this, all of the Ssu− substitutions mapping to the globular domain of eIF1 increase the affinity of eIF1 for reconstituted 40S•eIF1A complexes, and they also partially rescue the binding of eIF1 variants harboring K60 substitutions. Moreover, the Ssu− mutation with the largest effect on eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit (D61G) was found to delay eIF1 dissociation and destabilize TC binding in the PIN state of 43S•mRNA PICs reconstituted with the SUI5 or SUI3-2 variants of eIF5 or eIF2. Our experiments in the reconstituted system further revealed that SUI5 and SUI3-2 confer Sui− phenotypes, at least in part, by altering the rate of eIF1 dissociation from the PIC and the stability of TC binding in the PIN state independently of their possible effects on GTP hydrolysis by eIF2.

RESULTS

Ssu− substitutions in eIF1 cosuppress the Sui− and Gcd− phenotypes of eIF1A SE mutations

As noted above, we previously isolated Ssu− substitutions in eIF1 as suppressors of the SUI5 mutation in eIF5 (Martin-Marcos et al. 2011). The eIF1 Ssu− substitution T15A replaces Thr-15 with Ala in the unstructured N-terminal tail (NTT), and E48V and L51F alter closely spaced residues in the loop between β-strand 2 and α-helix 1 and the beginning of α1, respectively. (Henceforth, 48,51 designates the double substitution of these two residues.) D61G alters a residue near the C terminus of α1, and Q84H alters the first residue in helix α2 (Fig. 2A). Based on the crystal structure of the Tetrahymena 40S•eIF1 complex (Rabl et al. 2011), only D61G and Q84H alter residues located near the predicted eIF1•40S interface, although the location of T15 in the complex is unknown (Fig. 2B).

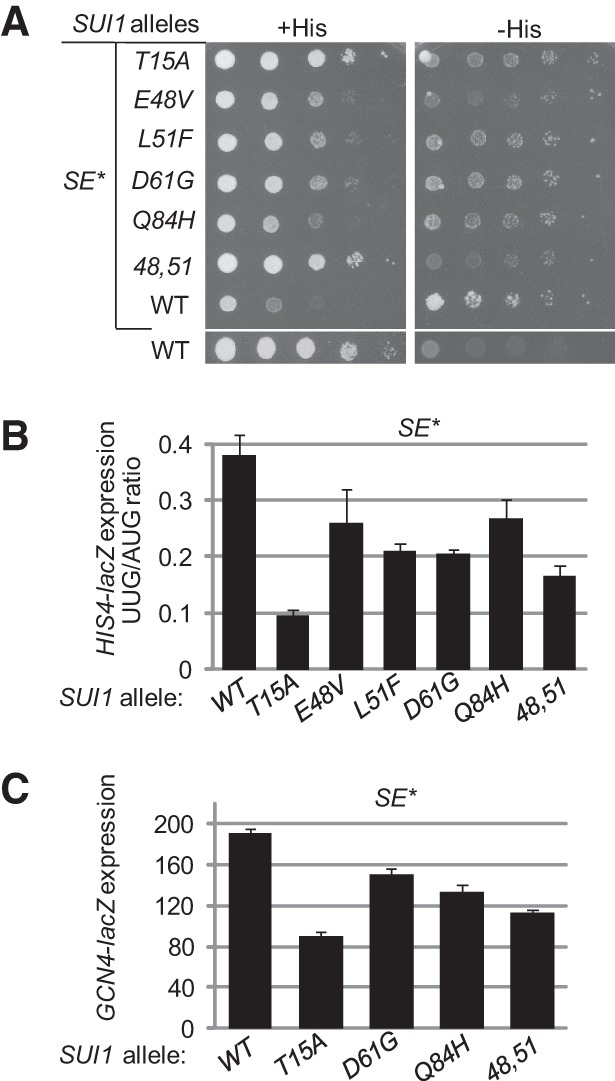

There is evidence that the Sui− phenotype of SUI5 involves contributions from the elevated GAP activity of the encoded mutant protein (eIF5-G31R) (Huang et al. 1997) and from the ability of the eIF5-G31R variant to promote rearrangement from the open-to-closed conformation of the PIC at near-cognate (UUG) codons (Maag et al. 2006). Only the latter mechanism has been implicated in the Sui− phenotype conferred by substitutions in the SE elements in the CTT of eIF1A (Saini et al. 2010). Hence, we reasoned that if the eIF1 Ssu− mutations were found to suppress the Sui− phenotype of eIF1A SE mutations in addition to suppressing SUI5, this would imply that they destabilize the closed conformation of the PIC as a means of reducing UUG initiation in vivo. To address this question, we employed a sui1Δ his4-301 PGAL-TIF11 strain, which lacks the chromosomal SUI1 gene encoding eIF1, harbors the his4-301 allele lacking the AUG start codon, and contains the chromosomal TIF11 allele (encoding eIF1A) under the glucose-repressible GAL1 promoter. The strain also harbors plasmid copies of SUI1+ and the tif11 allele encoding the eIF1A mutant with Ala substitutions in all SE residues except F131 (dubbed SE*). This strain can grow on glucose medium lacking histidine owing to the ability of the tif11-SE* product to increase initiation at the in-frame UUG start codon at his4-301 and confer a His+/Sui− phenotype. We used plasmid shuffling (Boeke et al. 1984) to replace episomal SUI1+with the plasmids encoding eIF1 Ssu− variants and tested the resulting strains for the His+ phenotype.

In accordance with previous results (Saini et al. 2010), in the control strain harboring SUI1+, the SE* mutation conferred growth on −His medium containing only 0.5% of the normal histidine supplement despite a strong slow-growth (Slg−) phenotype on +His medium (Fig. 3A, row 7). Interestingly, all of the eIF1 Ssu− mutations improved cell growth on +His medium while reducing or eliminating growth on −His medium, indicating cosuppression of the Slg− and Sui− phenotypes of the SE* mutation (Fig. 3A, rows 1–6). In the SUI1+ strain, the SE* mutation increased the UUG:AUG initiation ratio, measured by assaying matched HIS4-lacZ fusions harboring AUG or UUG start codons, to a level (∼0.4) that is 10-fold or more higher than that measured in WT strains (Saini et al. 2010). All of the eIF1 Ssu− mutations significantly reduced the UUG:AUG ratio, confirming that they suppress the Sui− phenotype of the eIF1A SE* mutation (Fig. 3B). This conclusion supports the idea that the Ssu− mutations destabilize the closed conformation as a means of reducing the elevated UUG initiation conferred by the eIF1A SE* mutation. We established previously that these eIF1 Ssu− substitutions reduce eIF1 abundance by exacerbating the deleterious effect of poor context at the SUI1 AUG codon (Martin-Marcos et al. 2011); hence, they do not impede rearrangement to the closed conformation by increasing the eIF1 concentration in the cell.

FIGURE 3.

SUI1 Ssu− mutations diminish the His+ and Slg− phenotypes, the elevated HIS4 UUG:AUG initiation ratio, and the derepressed GCN4-lacZ expression conferred by the eIF1A Sui− mutation tif11-SE*. (A) Derivatives of sui1Δ PGAL- TIF11 his4-301 strain PMY03 containing pAS5-130 (tif11-SE1*, SE2* + F131 [dubbed SE*]) and the indicated SUI1 alleles on sc plasmids were analyzed for Slg− and His+ phenotypes by spotting 10-fold serial dilutions on synthetic complete medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SC-Leu-Trp) and supplemented either with 0.3 mM histidine (+His) or 0.0015 mM His (−His). (B) Transformants of the strains from A also harboring plasmids p367 or p391 containing the HIS4-lacZ reporters with AUG or UUG start codon, respectively, were cultured in synthetic dextrose minimal medium (SD) supplemented with His at 30°C to A600 of ∼1.0, and β-galactosidase activities were measured in WCEs. The ratio of expression of the UUG to AUG reporter was calculated from two measurements on six independent transformants, and the mean and SEMs were plotted. (C) Transformants of the strains from A harboring the GCN4-lacZ fusion on plasmid p180 (rather than a HIS4-lacZ fusion) were cultured and analyzed as in B.

A second consequence of the SE* mutation is to reduce the rate of TC binding to the PIC (Saini et al. 2010), owing to the fact that it destabilizes the open conformation of the PIC that is permissive for rapid TC loading (Passmore et al. 2007). An in vivo manifestation of this defect is the derepression of GCN4 mRNA translation in nutrient-replete cells (the Gcd− phenotype), as a slower rate of TC loading allows 40S subunits that have translated upstream uORF 1 and resumed scanning to bypass the start codons at uORFs 2–4 and reinitiate at the GCN4 AUG codon in the absence of starvation-induced eIF2α phosphorylation (Hinnebusch 2005). The SE* mutation confers high-level expression of a GCN4-lacZ reporter in nonstarvation conditions (Fig. 3C) at a level 10-fold or more higher than that observed in WT cells (Saini et al. 2010). Consistent with our model, the Ssu− mutations T15A, D61G, Q84H, and the E48V,L51F double mutation all reduce GCN4-lacZ expression in the SE* mutant strains (Fig. 3C). We previously showed that overexpressing WT eIF1 does not suppress the Gcd− phenotype of this tif11-SE* mutation, even though it stabilizes the open conformation of the PIC (Saini et al. 2010). These data provide evidence for the notion that the eIF1 Ssu− mutations stabilize the POUT conformation of TC binding (impaired by SE mutations) in addition to promoting the open conformation of the 40S subunit.

Ssu− substitutions in eIF1 cosuppress the Sui− and Gcd− phenotypes of an eIF1 Sui− substitution at the 40S interface

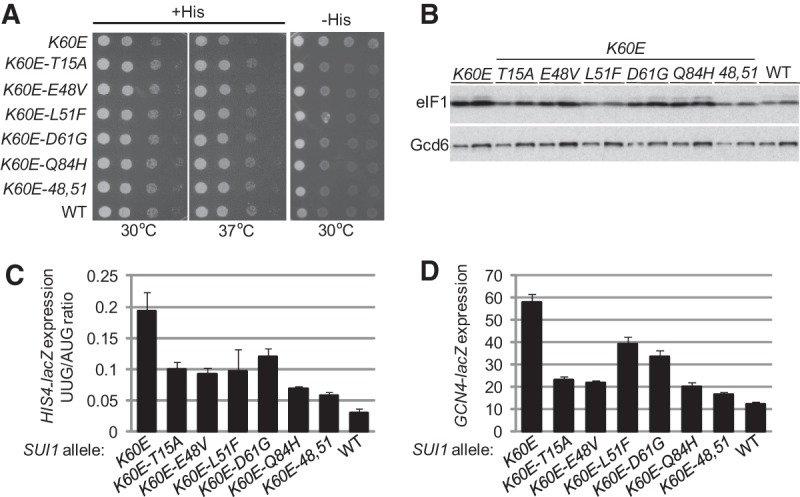

According to our model, the Ssu− phenotypes of the eIF1 substitutions could arise, at least partly, from increased affinity of eIF1 for the 40S subunit that would prevent inappropriate eIF1 dissociation from the PIC at UUG codons in Sui− mutants. Based on the Tetrahymena 40S•eIF1 crystal structure (Rabl et al. 2011), Lys-60 in helix α1 of yeast eIF1 is predicted to contact residue G1780 in 18S rRNA helix 45. Indeed, we showed recently that a K60E substitution impairs eIF1 binding to the 40S subunit in vitro and confers the Sui− and Gcd− phenotypes predicted from increased eIF1 dissociation from the open conformation of the PIC in vivo (Martin-Marcos et al. 2013). Hence, we asked whether the eIF1 Ssu− substitutions would compensate for K60E and cosuppress its associated Sui− and Gcd− phenotypes. To this end, plasmid-borne SUI1 alleles encoding the appropriate eIF1 double mutants were used to replace WT SUI1+ in a sui1Δ his4-301 strain by plasmid shuffling. As shown in Figure 4A, the K60E substitution confers a Slg− phenotype on +His medium and a His+ phenotype on −His medium, reflecting its Sui− phenotype. Importantly, all of the Ssu− substitutions diminish both the Slg− and Sui− phenotypes, as the double mutants more closely resemble the WT SUI1+ strain than the K60E single mutant on both media (Fig. 4A). All of the Ssu− substitutions also mitigate the elevated UUG:AUG initiation ratio (Fig. 4C) and depression of GCN4-lacZ expression (Gcd− phenotype) conferred by the K60E substitution (Fig. 4D). The K60E mutant is overexpressed (Fig. 4B, K60E vs. WT) owing to the ability of this Sui− substitution to reduce the impact of poor AUG context at the SUI1 start codon on eIF1 expression (Martin-Marcos et al. 2011). Interestingly, all of the double mutants are expressed at lower levels than the K60E single mutant (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the Ssu− substitutions reinstate at least partially the effect of poor context in diminishing recognition of the SUI1 AUG codon. Thus, it appears that the Ssu− substitutions increase the accuracy of start codon recognition by enforcing the requirement for both favorable sequence context and an AUG start codon for efficient initiation in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

SUI1 Ssu− mutations diminish the His+ and Slg− phenotypes, the elevated HIS4 UUG:AUG initiation ratio, and the derepressed GCN4-lacZ expression conferred by the Sui− allele sui1-K60E. (A) Tenfold serial dilutions of derivatives of sui1Δ his4-301 strain JCY03 containing the indicated SUI1 alleles on sc plasmids were spotted on SC-Leu supplemented with 0.3 mM histidine (+His) and cultured for 1.5 d at 30°C and 37°C and on SC-Leu plus 0.003 mM His (−His) media for 7 d. (B) Strains from A were cultured in SD supplemented with His, Trp, and uracil (Ura) at 30°C to an A600 of ∼1.0, and WCEs were subjected to Western analysis using antibodies against eIF1/Sui1 or eIF2Bε/Gcd6 (used as loading control). Two different amounts of each extract differing by a factor of two were loaded in successive lanes. (C) Transformants of strains from A also harboring plasmids p367 or p391 were cultured in SD+His+Trp at 30°C to an A600 of ∼1.0, and β-galactosidase activities were measured in WCEs; the mean and SEMs from two measurements on six independent transformants were plotted. (D) Transformants of the strains from A also harboring plasmid p180 were cultured and analyzed as in C.

Ssu− substitutions in the globular domain of eIF1 increase its affinity for the 40S subunit

Our finding that the eIF1 Ssu− mutations partially suppress the phenotypes of the K60E substitution, which likely eliminates a direct contact of eIF1 with the 40S subunit (Rabl et al. 2011), supports the model that they act by increasing eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit. This mechanism seems particularly likely for the D61G and Q84H substitutions because they alter residues predicted to reside at the 40S•eIF1 interface, <7 Å from 18S rRNA residues (Fig. 2B; Rabl et al. 2011). Moreover, D61G removes a negatively charged side-chain in helix α1, which harbors basic residues (K59, K60) that contact rRNA and thus could eliminate ionic repulsion between negatively charged D61 and the rRNA phosphodiester backbone. Interestingly, this Asp residue is not highly conserved, and some species contain a Lys residue at this position (Tetrahymena eIF1 contains a Trp [W54]) (Fig. 2A), so that depending on the nature of its side-chain, this residue could weaken (Asp, Glu) or strengthen (Lys) eIF1 binding to the 40S subunit. The Gln residue at position 84 is more highly conserved but is replaced by histidine in Tetrahymena eIF1 (Fig. 2A), so that the Q84H substitution introduces the residue normally found at this location in Tetrahymena eIF1. As noted above, the Ssu− mutations E48V and L51F do not alter residues at the 40S•eIF1 interface, and the location of T15 in the complex is unknown.

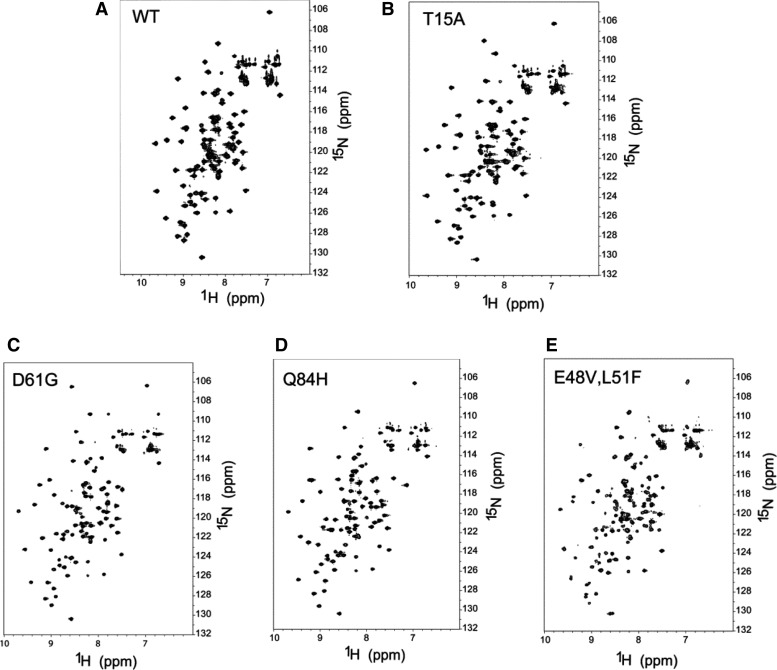

We began our in vitro analysis of the eIF1 Ssu− mutants by examining the effects of the mutations on the folding of eIF1 by examining NMR spectra of the mutant proteins in solution. The dispersion of the chemical shifts of the fingerprint 1H-15N HSQC-spectra was very similar for WT eIF1, the single mutants T15A, D61G, and Q84H, and the E48V,L51F double mutant (Fig. 5A–E). These results indicate that none of the substitutions produces a detectable alteration in the tertiary structure of eIF1.

FIGURE 5.

NMR analysis of eIF1 mutant proteins. 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 0.2 mM 15N-labeled WT (A), T15A (B), D61G (C), Q84H (D), and E48V,L51F (E) eIF1proteins.

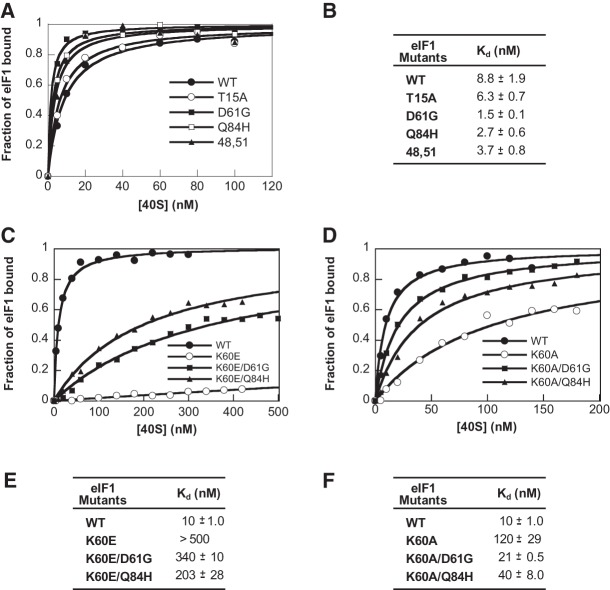

To test the effects of the Ssu− substitutions on 40S binding, the mutant eIF1 proteins were fluorescently labeled with fluorescein (fl), and the fraction of eIF1-fl bound to 40S subunits in the presence of a saturating concentration of eIF1A was measured at different concentrations of 40S subunits by monitoring the change in fluorescence anisotropy. eIF1A was included in this assay because 40S binding of eIF1 and eIF1A is thermodynamically coupled (Maag and Lorsch 2003). Interestingly, D61G and Q84H increased eIF1 affinity for the 40S•eIF1A complex, decreasing the Kd by factors of about six and about three, respectively. The E48V,L51F substitutions produced a smaller increase in affinity, whereas T15A did not alter eIF1 affinity for the 40S•eIF1A complex (Fig. 6A,B). These findings are consistent with the idea that D61G, Q84H, and E48V,L51F produce their Ssu− phenotypes at least to some extent by increasing eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit, thus impeding eIF1 dissociation and rearrangement to the closed complex at UUG start codons.

FIGURE 6.

Ssu− mutations in eIF1 increase the affinity of eIF1 for 40S•eIF1A complexes in vitro. (A) Fluorescein (fl)-labeled WT or Ssu− eIF1 mutant proteins were mixed with increasing concentrations of 40S subunits in the presence of 1 μM eIF1A, and the increase in fluorescence anisotropy was measured. (B) Kd values from panel A calculated by fitting the data with hyperbolic binding equations. Values are the average of at least three independent experiments. (C,D) Binding of fl-labeled WT or the indicated mutant eIF1 proteins to 40S subunits in the presence of 1 μM eIF1A was measured as in A. (E,F) Kd values from panels C and D calculated from fitting with hyperbolic binding equations. The values for K60E/D61G and K60E/Q84H are estimates because saturation could not be achieved at experimentally achievable concentrations of 40S subunits. The value for K60E is a lower limit because only the linear phase of the binding curve could be observed.

Because the Ssu− substitutions diminish the Sui− phenotype of the K60E mutation, we sought to demonstrate that they would also confer increased 40S binding by the eIF1 double mutants harboring both substitutions. Indeed, whereas the K60E variant shows negligible binding, combining D61G or Q84H with K60E restored appreciable eIF1 binding to 40S•eIF1A complexes, albeit well below the WT eIF1 binding affinity (Fig. 6C,E). We showed recently that the K60A substitution also produces a Sui− phenotype that is weaker in degree than that of K60E, most likely because it only removes a basic side-chain rather than introducing an acidic side-chain at this position (Martin-Marcos et al. 2013). Consistent with this, K60A increases the Kd for eIF1 binding to 40S•eIF1A complexes by approximately 12-fold, whereas combining D61G or Q84H with K60A decreased the Kd by factors of about six or about three, respectively (Fig. 6D,F). These findings support the conclusion that the D61G and Q84H Ssu− substitutions restore rapid TC loading to 40S subunits and suppress UUG initiation in vivo at least in part by increasing the affinity of eIF1 for the open conformation of the 40S subunit.

Ssu− substitutions D61G and Q84H delay eIF1 dissociation on start codon recognition

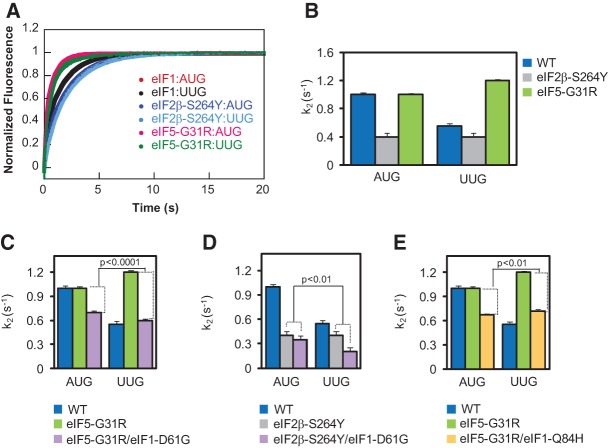

To provide further evidence that eIF1 Ssu− substitution D61G reduces UUG initiation in Sui− mutants by impeding eIF1 release from the PIC, we measured the rate of eIF1 dissociation at the start codon in reconstituted PICs containing all other WT components or harboring Sui− variants of eIF2 or eIF5. To this end, 43S PICs were assembled with fl-labeled eIF1 and tetramethylrhodamine-labeled eIF1A (eIF1A-TAMRA), and unlabeled TC and eIF5. eIF1A-TAMRA acts as the energy acceptor in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between eIF1-fl and eIF1A-TAMRA in these PICs. Addition of model mRNA evokes a biphasic loss of FRET and an attendant increase in eIF1-fl fluorescence, monitored by stopped-flow fluorometry, with the faster phase of the reaction corresponding to displacement of eIF1 from eIF1A within the PIC and the slower phase corresponding to eIF1 dissociation from the PIC. (Although these reactions lack eIF3, which might be expected to influence eIF1 release [Valasek et al. 2004], we showed previously that inclusion of eIF3 had no discernible effect on rate constants of eIF1 dissociation from reconstituted PICs [Maag et al. 2005]). In accordance with previous results (Maag et al. 2005), in PICs reconstituted with WT eIF1, the rate constant for the slower phase of the reaction (k2) is about twofold higher for a model mRNA containing an AUG versus UUG start codon (mRNA(AUG) vs. mRNA(UUG)), indicating reduced rates of eIF1 dissociation at a near-cognate versus cognate start codon (Fig. 7A, eIF1:AUG vs. eIF1:UUG; blue bars in Fig. 7B). (Note that in Fig. 7A, the data points for the eIF1:AUG and eIF5-G31R:AUG experiments are not readily distinguished because they overlap extensively.)

FIGURE 7.

The sui1-D61G Ssu− mutation decreases the rate of eIF1 dissociation in reconstituted 48S PICs. (A,B) eIF1 release was monitored by following the decrease in FRET between eIF1-fl and eIF1A-TAMRA in 43S complexes formed with WT eIF5 or eIF5-G31R and TC containing WT eIF2 or eIF2 harboring the eIF2β-S264Y variant, as indicated, after addition of mRNA (AUG or UUG) and excess unlabeled eIF1. The increase in fl fluorescence was monitored by stopped-flow fluorometry, and curves were fit with double exponential rate equations. The fast phase corresponds to a conformational change and the slow phase (k2) to eIF1 release. The k2 values measured in replicate experiments were averaged and plotted; error bars, SEMs. (C,D) The D61G substitution in eIF1 decreases the rate of eIF1 release (k2) in 43S•mRNA complexes made with eIF5-G31R (C) or TC containing eIF2β-S264Y (D). The results in C for reactions containing WT eIF5 and WT eIF1 (blue) or eIF5-G31R and WT eIF1 (green) are replotted from B for comparison with those obtained in reactions combining eIF5-G31R with eIF1-D61G (purple). A Student's t-test indicates that the reduction in k2 evoked by D61G is significantly greater for PICs with mRNA(UUG) versus mRNA(AUG) in reactions containing eIF5-G31R (differences between heights of purple and green bars; P < 0.0001). The data in D were treated identically as in C, and a t-test indicates that the reduction in k2 evoked by D61G is significantly greater for PICs with mRNA(UUG) versus mRNA(AUG) in reactions containing eIF2β-S264Y (differences between heights of purple and gray bars; P < 0.01). (E) The Q84H substitution in eIF1 decreases the rate of eIF1 release in 43S•mRNA complexes made with eIF5-G31R. The data were treated identically as in C, and a t-test indicates that the reduction in k2 evoked by Q84H is significantly greater for PICs with mRNA(UUG) versus mRNA(AUG) in reactions containing eIF5-G31R (differences between heights of green and yellow bars; P < 0.01).

Interestingly, replacing WT eIF5 with the Sui− variant eIF5-G31R (encoded by SUI5) increased k2 by a factor of about 2.2 for mRNA(UUG), with little or no effect on k2 for mRNA(AUG), largely eliminating the differential effects of AUG and UUG start codons on the rate of eIF1 dissociation (Fig. 7A,B, green bars). This alteration should contribute to the increased UUG:AUG initiation ratio conferred by SUI5 in vivo (Huang et al. 1997). As nonhydrolyzable GDPNP was used in the TC assembled for these assays, the effect of eIF5-G31R in stimulating eIF1 dissociation at UUG codons occurs independently of GTP hydrolysis and Pi release by eIF2-GDP and thus likely reflects the ability of this eIF5 mutant to stabilize the closed/PIN conformation from which eIF1 is released at UUG codons.

Replacing WT eIF2 with the mutant eIF2 complex harboring the Sui− variant eIF2β-S264Y (encoded by SUI3-2) also distorted the differential in k2 values between AUG and UUG but by a different mechanism, decreasing k2 by a factor of about 2.3 specifically for mRNA(AUG) (Fig. 7B, gray bars). This alteration should contribute to the increased UUG:AUG initiation ratio conferred by SUI3-2 in vivo (Huang et al. 1997) by preferentially reducing initiation at AUG codons. Interestingly, this latter mechanism was described previously for the eIF1 Sui− substitution G107R, which also delays eIF1 dissociation specifically at AUG codons (Nanda et al. 2009). Again, the effect of the S264Y substitution on eIF1 dissociation kinetics occurs in the absence of GTP hydrolysis, implicating the zinc-binding domain of eIF2β (harboring WT S264) in regulating the open/POUT-to-closed/PIN transition of the PIC and attendant eIF1 release apart from any effects on GTP hydrolysis/Pi release.

When the Ssu− mutant eIF1-D61G replaced WT eIF1 in reactions containing eIF5-G31R, it reduced k2 for both start codons but evoked a significantly greater reduction at UUG (∼50%) than at AUG (∼30%) (Fig. 7C, purple vs. green bars, UUG vs. AUG). Similarly, the D61G substitution reduced k2 in reactions containing eIF2β-S264Y, with a considerably larger effect at UUG (∼50%) than at AUG (∼12%) (Fig. 7D, purple vs. gray bars, AUG vs. UUG). The reduced rates of eIF1 dissociation (k2 values) conferred by D61G in reactions containing eIF5-G31R or eIF2β-S264Y (Fig. 7C,D) are consistent with the fact that D61G increases eIF1 affinity for the 40S•eIF1A complex (Fig. 6B). The finding that D61G reduces the rate of eIF1 dissociation (k2) to a greater extent at UUG versus AUG codons in reactions containing eIF5-G31R or eIF2β-S264Y, restoring in both cases a somewhat higher k2 value at AUG versus UUG (Fig. 7C,D), helps to explain the reduction in UUG:AUG initiation ratio conferred by D61G (its Ssu− phenotype) in cells expressing these Sui− variants of eIF5 and eIF2 (Fig. 2C).

Similar results were obtained for the eIF1 Ssu− substitution Q84H in reactions containing eIF5-G31R. The Q84H substitution reduced the rate of eIF1 dissociation (k2 value) for both start codons, indicating destabilization of the closed/PIN state, and conferred a somewhat greater reduction in k2 at UUG (∼40%) than at AUG (∼30%) (Fig. 7E, yellow vs. green bars, UUG vs. AUG). This result is consistent with the increase in eIF1 affinity for the 40S•eIF1A complex observed for the Q84H mutant (Fig. 6B) and with the Ssu− phenotype (decreased UUG:AUG ratio) displayed by Q84H in cells expressing the Sui− variant eIF5-G31R (Fig. 2C).

Ssu− substitution D61G destabilizes the PIN state of TC binding to the PIC

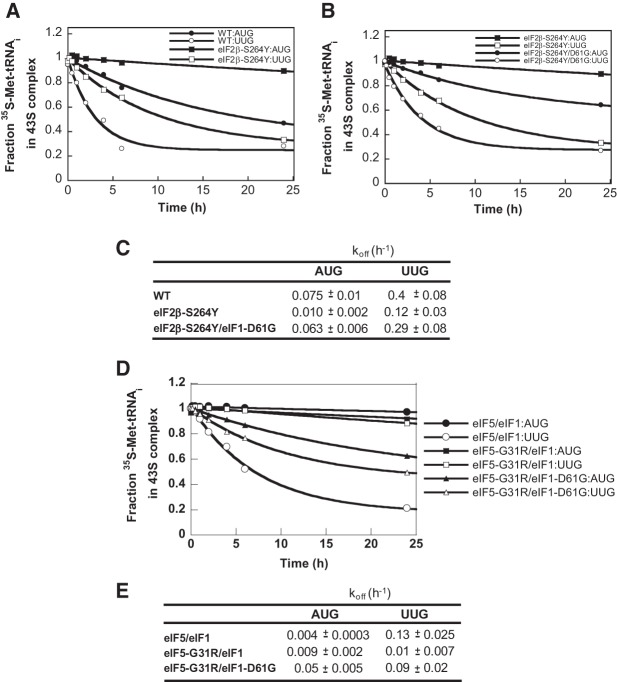

Our finding that D61G decreases the rate of eIF1 dissociation on start codon recognition (Fig. 7C,D) leads to the prediction that it should also impede transition of the PIC from the open/POUT conformation to the closed/PIN state in which the TC is more tightly bound to the P site (Passmore et al. 2007). To test this prediction, we compared the kinetics of Met-tRNAiMet dissociation from PICs reconstituted with WT eIF1 or eIF1-D61G. The TC was assembled with [35S]-labeled Met-tRNAiMet and bound to 40S subunits in the presence of mRNA(AUG) or mRNA(UUG) and saturating concentrations of eIF1A and either mutant or WT eIF1. Binding of the TC to the 40S subunit decreases its electrophoretic mobility in a native gel, and dissociation of the TC from the 40S is measured by quantifying the amount of [35S]Met-tRNAiMet remaining in the slowly migrating complex over time when “chased” with excess unlabeled TC. In accordance with previous results, the rate at which the labeled TC dissociates from the PIC (koff) is more than fivefold lower for mRNA(AUG) versus mRNA(UUG) (Fig. 8A,C, WT:AUG vs. WT:UUG), reflecting the greater stability of the PIN state at the cognate versus near-cognate start codon (Kolitz et al. 2009).

FIGURE 8.

Ssu− mutant eIF1-D61G destabilizes the PIN state in the presence of Sui− variants eIF2β-S264Y and eIF5-G31R in vitro. (A–C) Rate of TC dissociation (koff) from 43S•mRNA(AUG) or (UUG) complexes formed with TC containing [35S]-Met-tRNAiMet and WT eIF2 or the mutant eIF2 harboring eIF2β-S264Y, and either WT eIF1 or eIF1-D61G, as indicated. The koff values were determined by adding a chase of excess (300-fold or more) unlabeled TC, and the fraction of labeled TC bound to the 40S subunits was monitored over time using native gels. Values are the averages of two or three independent experiments. The results in B for eIF2β-S264Y and WT eIF1 are replotted from A for comparison. (D,E) koff measurements were conducted as in A through C for reactions containing eIF5 or eIF5-G31R and eIF1 or eIF1-D61G, as indicated.

Interestingly, replacing WT eIF2 with the Sui− variant harboring eIF2β-S264Y evoked a decrease in koff for both AUG and UUG mRNAs, indicating stabilization of the PIN state. In fact, with this eIF2 mutant, the koff at UUG (0.12 h−1) is only about 1.6-fold higher than the koff at AUG measured for WT eIF2 (0.075 h−1) (Fig. 8A,C, WT vs. eIF2β-S264Y). This finding is consistent with the increased UUG:AUG initiation ratio in cells harboring SUI3-2, provided that we also stipulate that the hyperstability of the PIN state observed for the mRNA(AUG) complex containing eIF2β-S264Y does not increase the AUG initiation rate above that seen in WT cells. This is a reasonable assumption as the PIN state at AUG for WT PICs is expected to be optimized for efficient initiation. Note that because the TC is assembled with GDPNP in these assays, the results support the idea that eIF2β-S264Y stabilizes the closed/PIN state of the PIC at least partly by a mechanism independent of GTP hydrolysis or Pi release.

Importantly, when WT eIF1 was replaced with the Ssu− variant eIF1-D61G in reactions containing eIF2β-S264Y, the koff was increased for both AUG and UUG mRNAs (Fig. 8B,C), indicating destabilization of the PIN state. The fact that the D61G substitution restores nearly WT values of koff for AUG and UUG in reactions containing eIF2β-S264Y is consistent with its ability to lower the UUG:AUG initiation ratio (Ssu− phenotype) in SUI3-2 cells (Fig. 2C).

We also examined the effect of eIF1-D61G on the stability of the PIN state in the presence of the eIF5-G31R variant. The addition of WT eIF5 stabilized TC binding to 43S•mRNA complexes, reducing the koff considerably compared with reactions lacking eIF5 for both AUG and UUG start codons (Fig. 8, cf. E, eIF5/eIF1, and C, WT), consistent with the previously reported effects of eIF5 on TC binding affinity (Nanda et al. 2009). Remarkably, replacing WT eIF5 with eIF5-G31R dramatically reduced the koff for mRNA(UUG) while slightly increasing the koff for mRNA(AUG) (Fig. 8D,E, eIF5-G31R/eIF1 vs. eIF5/eIF1). As such, eIF5-G31R essentially eliminates the strong (about 30-fold) differential in koff values between AUG and UUG complexes seen in the presence of eIF5 (Fig. 8E). This observation is consistent with the elevated UUG:AUG initiation ratio conferred by eIF5-G31R in vivo. It is also concordant with our previous finding (deduced from measuring eIF1A dissociation kinetics) that eIF5-G31R stabilizes the closed conformation of the PIC at UUG while destabilizing the complex at AUG (Maag et al. 2006). Notably, replacing WT eIF1 with eIF1-D61G in reactions containing eIF5-G31R increased the koff for both start codons, with a somewhat greater effect for mRNA(UUG) (ninefold) versus mRNA(AUG) (5.5-fold) (Fig. 8D,E, eIF5-G31R/eIF1-D61G vs. eIF5-G31R/eIF1). The increase in koff conferred by eIF1-D61G is consistent with our conclusion above that this eIF1 variant destabilizes the PIN state by reducing its rate of release from the PIC, and the relatively greater increase in koff observed at UUG versus AUG in these reactions (Fig. 8E) should contribute to the ability of eIF1-D61G to diminish the elevated UUG:AUG ratio (Ssu− phenotype) in cells expressing eIF5-G31R (Fig. 2C).

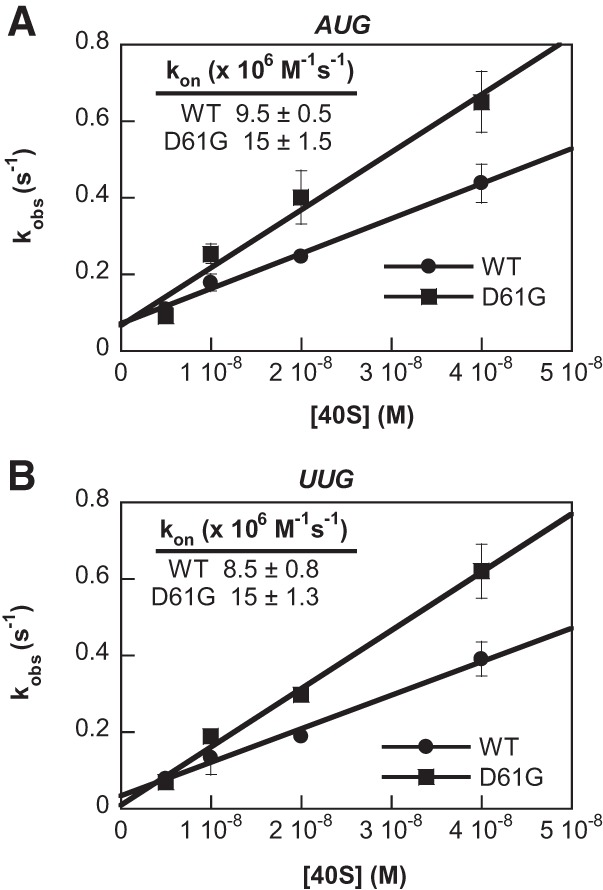

Ssu− substitution D61G increases the rate of TC loading in vitro

A prediction of our conclusion that the Ssu− mutant eIF1-D61G destabilizes the closed/PIN state is that it should also accelerate loading of TC onto the 40S subunit by shifting the equilibrium toward the open/POUT state to which TC binds most rapidly. This phenotype was observed previously for the eIF1A Ssu− substitution 17–21 (Saini et al. 2010). To test this prediction, we measured the kinetics of TC binding to 40S•eIF1A• eIF1•mRNA complexes containing WT or mutant eIF1 using the gel mobility shift assay described above. The TC was preassembled with [35S]-labeled Met-tRNAiMet, and the reaction was terminated at each time point with a chase of excess unlabeled TC. As described previously, the pseudo-first-order rate constant (kobs) was measured at different 40S subunit concentrations, from which the second order rate constant (kon) was calculated (Kolitz et al. 2009). In accordance with our prediction, the D61G substitution produces an approximately 1.6-fold to 1.8-fold increase in kon for both mRNA(AUG) and mRNA(UUG) (Fig. 9A,B). That an increase was observed with either start codon in the mRNA is consistent with the notion that eIF1-D61G accelerates the initial step of TC binding, which should be unaffected by the nature of the start codon (Kolitz et al. 2009). We presume that eIF1-D61G alters the equilibrium between the open (eIF1-bound) and closed (eIF1-free) states of the 40S subunit to favor the former, thereby increasing the proportion of total 40S subunits capable of rapid loading of TC in the POUT conformation.

FIGURE 9.

Ssu− mutant eIF1-D61G accelerates TC recruitment in vitro. (A,B) Rate constants for binding of TC to 40S subunits were determined by measuring the observed rate constants for binding (kobs) at different concentrations of 40S subunits. The fraction of [35S]-Met-tRNAiMet associated with 40S subunits in the presence of saturating amounts of WT eIF1 or eIF1-D61G, eIF1A, and mRNA with an AUG (A) or UUG (B) start codon was measured as a function of time at each concentration of 40S subunits using the native gel assay. The kobs values were determined by fitting the data with a single exponential rate equation and then plotted against the concentration of 40S subunits and fit with the equation for a straight line to obtain the second-order rate constant of TC binding to 40S subunits (kon) as the slope of the line. Values are the averages of two or three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

According to our model for the mechanism of scanning and AUG recognition, eIF1 and the SE elements in the eIF1A CTT carry out a dual function of stabilizing the open/POUT conformation of the PIC and impeding rearrangement to the closed/PIN state (Fig. 1A). Because TC binds more rapidly to the open conformation (Passmore et al. 2007), eIF1 and the eIF1A SE elements accelerate TC binding to 40S subunits and thus promote assembly of 43S and 43S•mRNA PICs. As they also inhibit rearrangement to the closed conformation in the absence of a perfect AUG:anticodon duplex in the P site, eIF1 and the SE elements increase the accuracy of initiation. Accordingly, mutations that reduce eIF1 binding to the 40S subunit or inactivate the SE elements in eIF1A reduce the rate of TC loading in vitro and confer a Gcd− phenotype in vivo and simultaneously decrease initiation accuracy by allowing selection of near-cognate start codons (the Sui− phenotype) (Fig. 1B; Cheung et al. 2007; Saini et al. 2010; Martin-Marcos et al. 2013). We reasoned that a crucial test of our model could be conducted by examining the consequences of eIF1 mutations having the opposite effect on AUG selection, i.e., conferring a hyperaccuracy phenotype. We previously identified such Ssu− substitutions in eIF1 that suppress elevated UUG initiation in the Sui− mutants SUI5 (eIF5-G31R) or SUI3-2 (eIF2β-S264Y) (Martin-Marcos et al. 2011), and we established here that they also suppress the Sui−, slow-growth, and Gcd− phenotypes conferred by substitutions in the eIF1A SE elements. These last findings suggested that the eIF1 Ssu− substitutions destabilize the closed/PIN state of the PIC and favor the open/POUT conformation that is conducive to rapid TC loading and scanning (Fig. 1C).

Importantly, we found that the eIF1 Ssu− substitutions also cosuppress the Sui−, Slg−, and Gcd− phenotypes of the eIF1 substitution K60E, recently shown to eliminate a direct contact of eIF1 with 18S rRNA in the 40S subunit (Rabl et al. 2011; Martin-Marcos et al. 2013). This implies that the eIF1 Ssu− substitutions can compensate for decreased eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this interpretation, we found that the eIF1 Ssu− substitutions mapping in the globular domain (D61G, Q84H, and the E48V,L51F double substitution) increase the affinity of otherwise WT eIF1 for reconstituted 40S•eIF1A PICs. Moreover, D61G and Q84H reduced the deleterious effects of K60E and K60A on eIF1 binding to 40S•eIF1A complexes in the relevant eIF1 double mutants. These findings suggest that D61G and Q84H impede rearrangement to the closed/PIN state at least partly by delaying eIF1 dissociation from the 40S subunit. Providing strong support for this interpretation, we showed that D61G decreases the rate of eIF1 dissociation in PICs reconstituted with the Sui− variants eIF5-G31R or eIF2β-S264Y. Similar observations were made for the Q84H variant in reactions reconstituted with eIF5-G31R. Furthermore, D61G increases the dissociation rate of TC from PICs reconstituted with eIF2β-S264Y or eIF5-G31R, while increasing the rate of TC loading on otherwise WT 43S•mRNA complexes in vitro. These last observations are in agreement with the previous conclusion that WT eIF1 accelerates TC binding but prevents TC from isomerizing to a more stable conformation (Passmore et al. 2007). Thus, by tightening eIF1•40S interaction, D61G stimulates the rate of TC loading in the POUT state by increasing the proportion of 40S subunits in the open, eIF1-bound conformation but also destabilizes TC binding in the PIN conformation by impeding eIF1 release. This is the same molecular mechanism we established for Ssu− substitutions in the eIF1A N-terminal SI element (Saini et al. 2010), supporting the idea that eIF1 and the eIF1A SE elements cooperate in their dual functions of promoting the open/POUT state while antagonizing the closed/PIN state, of the PIC.

The effects of D61G and Q84H in stabilizing the eIF1•40S interaction are readily understood in the context of the eIF1–40S crystal structure, as they reside close to the eIF1•40S interface (Fig. 2B; Rabl et al. 2011). D61G eliminates a negative charge in helix α1, which should decrease ionic repulsion with the phosphodiester backbone of 18S rRNA. Interestingly, this residue varies between acidic and basic residues throughout phylogeny (Fig. 2A), suggesting a variable role in weakening or strengthening eIF1•40S contact and thereby influencing initiation accuracy. It is possible that this residue covaries with one or more other eIF1 residues at the 40S interface and that the overall affinity remains constant across phylogeny but is achieved with different combinations of residues. Q84 is more highly conserved, being replaced by Lys or His in Tetrahymena and certain other lower eukaryotes (Fig. 2A) for an extra positive charge at the eIF1•40S interface. Indeed, our Ssu− substitution Q84H introduces histidine at this position, which should strengthen 40S binding by eIF1. In contrast, E48 and L51 are distant from the eIF1•40S interface (Fig. 2B). Noting that the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the E48V,L51F variant revealed no major alteration of tertiary structure, perhaps these substitutions alter the conformational flexibility of eIF1 in a way that promotes 40S contacts by helix α1 or the β1-β2 hairpin loop (Rabl et al. 2011).

The fact that E48V,L51F confers an Ssu− phenotype comparable to that of D61G (Fig. 2C) without a commensurate increase in eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit (Fig. 6B) might indicate that E48V and L51F enhance an additional contact of eIF1 within the PIC. The same conclusion applies to the T15A substitution, which has a potent Ssu− phenotype but no effect whatsoever on eIF1•40S binding affinity in vitro. Considering that eIF1 interacts with segments of eIF3c, eIF5, and eIF2β within the multifactor complex (Asano et al. 2000; Singh et al. 2004), one or more of these interactions might be strengthened by E48V,L51F or T15A in a manner that delays eIF1 release from the PIC on start codon recognition. Conferring a new or stronger interaction of eIF1 with Met-tRNAi is another possibility in view of the predicted proximity of these two macromolecules in the PIC (Rabl et al. 2011; Lomakin and Steitz 2013). Alternatively, these substitutions might stimulate a conformational change that disfavors rearrangement from the POUT to PIN states without increasing the affinity of eIF1 for the PIC, e.g., by increasing the clash between eIF1 and Met-tRNAi thought to impede formation of the codon:anticodon duplex at the start codon (Rabl et al. 2011; Lomakin and Steitz 2013). We recently came to an analogous conclusion regarding a Sui− substitution in the eIF1 NTT that does not weaken eIF1 binding to 40S•eIF1A complexes in vitro but stabilizes the PIN mode of TC binding and thus might mitigate a clash between the eIF1 NTT and Met-tRNAi (Martin-Marcos et al. 2013).

Previous in vitro analysis of the eIF5-G31R (SUI5) variant led to the conclusion that it confers a Sui− phenotype by increasing the GAP activity of eIF5, evoking inappropriate dissociation of eIF2-GDP from Met-tRNAi at non-AUG codons (Huang et al. 1997). Our results indicate that eIF5-G31R increases both the rate of eIF1 dissociation and the stability of TC binding (decreases koff) specifically at UUG codons and that it also destabilizes TC binding (increasing koff) at AUG codons. Previously, we concluded that eIF5-G31R stabilizes the closed conformation of the PIC at UUG codons, while having the opposite effect at AUG codons, on the basis of its stabilizing effect on eIF1A association with the PIC (Maag et al. 2006). Considering that all of the assays employed to reach these conclusions involve TC assembled with nonhydrolyzable GDPNP, the deduced effects of eIF5-G31R on conformational transitions in the PIC must be engendered independently of its GAP function. It could be argued that the GDPNP analog evokes nonphysiological effects in our assays. However, the fact that eIF5-G31R preferentially accelerates eIF1 release from, and stabilizes TC binding to, 43S•mRNA complexes harboring UUG versus AUG start codons is fully consistent with its Sui− phenotype. Moreover, the fact that eIF1-D61G mitigates both of these biochemical defects fits well with its Ssu− phenotype. The concordance between the effects of these mutations in vitro and in vivo provides strong evidence that the biochemical defects uncovered for the eIF5-G31R variant in assays involving GDPNP represent physiological contributions to its Sui− phenotype. In agreement with previous findings (Maag et al. 2006), we conclude that eIF5-G31R promotes UUG initiation at least partly by increasing the probability of rearrangement from the open/POUT to closed/PIN conformation at UUG codons with attendant release of eIF1. This defect can be diminished by increasing eIF1 affinity for the 40S subunit by an eIF1 Ssu− substitution.

Our observation that eIF5 stabilizes TC binding to 43S•mRNA complexes (Fig. 8E) seems consistent with our previous finding that eIF5 enhances TC binding to the PIC by promoting eIF1 release, although this effect was most pronounced for a near-cognate codon (AUU) and with eIF1 variants that display abnormally slow release and was relatively small for WT eIF1 at AUG codons (Nanda et al. 2009). In fact, we reported recently that interaction of the eIF2β-NTT with the eIF5-CTD stabilizes the PIN state (Fig. 1A). While this eIF2β·eIF5 interaction appears to facilitate release of eIF1 from the eIF5-CTD and subsequent dissociation of eIF1 from the PIC (Luna et al. 2012), it might also stabilize the PIN state by helping to anchor TC tightly to the P site. However, neither mechanism can readily explain why we observed a greater reduction in koff at AUG versus UUG on addition of eIF5 (Fig. 8E). It also remains unclear how the G31R substitution in the eIF5 NTD specifically stabilizes the closed/PIN state at UUG while having the opposite effect at AUG (Fig. 8E; Maag et al. 2006). Perhaps G31R alters interaction of the eIF5 NTD with eIF2 in a way that indirectly alters the orientation of TC in the P site to disfavor base-pairing with AUG while enhancing base-pairing with UUG. If so, then WT eIF5 might be capable of preferentially stabilizing the perfect codon:anticodon duplex at AUG.

Previous in vitro analysis of the eIF2β-S264Y (SUI3-2) substitution indicated that its Sui− phenotype results primarily from increasing the intrinsic (eIF5-independent) GTPase activity of eIF2 to permit release of eIF2-GDP from Met-tRNAi at non-AUG codons (Huang et al. 1997). Surprisingly, we found here that eIF2β-S264Y provokes a different defect that likely contributes to the elevated UUG:AUG initiation ratio conferred by this mutation in vivo, of reducing eIF1 release preferentially at AUG codons in PICs with TC assembled using nonhydrolyzable GDPNP. This mechanism was established previously for the eIF1-G107R Sui− substitution (Nanda et al. 2009). Because eIF1-D61G reduces eIF1 dissociation substantially at UUG but not at AUG codons in PICs reconstituted with eIF2 containing eIF2β-S264Y, it overcomes the effect of eIF2β-S264Y and reinstates more rapid eIF1 release at AUG versus UUG codons (Fig. 7D). Thus, our results lead to the unexpected inference that eIF2β-S264Y, as well as eIF5-G31R, affects start codon recognition at least partly by altering the rate of rearrangement from the open to closed conformation of the PIC.

It is not obvious how a substitution in the zinc-binding domain of eIF2β would exert this effect. One possibility would be that eIF2β-S264Y prevents the eIF2β-NTT from releasing eIF1 and binding to the eIF5-CTD, which should impede dissociation of eIF1 from the PIC (Fig. 1A; Nanda et al. 2013). However, interaction between the eIF2β zinc-binding domain and its NTT has not been reported, and it is also unclear why this would happen at AUG, but not at UUG, start codons. Another possibility might be that eIF2β-S264Y alters the orientation of Met-tRNAi binding to eIF2 in a way that diminishes the clash between eIF1 and Met-tRNAi engaged in a perfect duplex with AUG in the PIN state, thus reducing the rate of eIF1 release. If this clash is mitigated by the mismatch at the first position of the codon:anticodon duplex formed at UUG, it could explain why eIF2β-S264Y has a smaller effect on eIF1 release at UUG versus AUG codons.

Our finding that eIF2β-S264Y decreases the rate of eIF1 dissociation at AUG codons (Fig. 7B) might seem at odds with the fact that it also increases the stability of TC binding to the PIC at AUG (Fig. 8A,C), as eIF1 dissociation enables rearrangement to the PIN state with TC bound more tightly to the PIC. However, the first assay measures the rate at which eIF1 is released from the PIC to achieve the PIN state (which is slowed down at AUG by eIF2β-S264Y), while the second assay measures the stability of the PIN state once eIF1 is released (which is elevated by eIF2β-S264Y). Our proposal above that eIF2β-S264Y diminishes the clash between eIF1 and Met-tRNAi bound in the PIN state at AUG codons can account for these ostensibly contradictory effects, as a diminished clash with Met-tRNAi should reduce the rate of ejecting eIF1 from the complex but then should also render the TC immune to the destabilizing effect of eIF1 reassociation with the PIC.

The ability of the D61G substitution to reduce the rate of eIF1 release at UUG codons in reactions with eIF2β-S264Y (Fig. 7D) can be attributed simply to the higher affinity of eIF1-D61G for the 40S subunit. This property can also explain its ability to destabilize the TC bound to the PIC at AUG or UUG start codons (Fig. 8C) by favoring the reassociation of eIF1-D61G with the 40S subunit and attendant shift from PIN to POUT with TC less tightly bound to the P site. To explain why eIF1-D61G does not further reduce the rate of eIF1-D61G release at AUG codons in reactions with eIF2β-S264Y (Fig. 7D), it can be proposed that D61G also increases the clash between eIF1 and Met-tRNAi base-paired with AUG (PIN), offsetting its increased affinity for the 40S subunit.

In summary, our findings indicate that the affinity of eIF1 for the 40S subunit is finely tuned to optimize the accuracy of selecting AUG as the translation initiation codon. Substituting the side-chain of a single residue located at the 40S binding surface of eIF1 can increase or decrease initiation accuracy by delaying or accelerating eIF1 release, respectively, in response to the predicted clash between eIF1 and Met-tRNAi base-paired with the P-site codon (Rabl et al. 2011; Lomakin and Steitz 2013). Because the TC loads rapidly only to the open conformation of the PIC stabilized by eIF1 (Passmore et al. 2007), these eIF1 residues also influence the rate of TC loading on 40S subunits and are thus crucial for the reinitiation mechanism that governs translation of GCN4 mRNA (Hinnebusch 2005) and expression of the myriad genes dependent on Gcn4 for high-level transcription under nutrient starvation conditions (Natarajan et al. 2001). It will be interesting to learn whether regulatory mechanisms exist that modulate affinity of WT eIF1 for the 40S subunit and thereby alter initiation accuracy and the efficiency of reinitiation in the manner observed here for eIF1 mutations. Our results also provide support for the notion that eIF5 enhances AUG recognition in a manner beyond its role as GAP for GTP hydrolysis in the TC by promoting eIF1 dissociation and participating in other interactions, e.g., with the eIF2β-NTT (Luna et al. 2012), that stabilize the closed/PIN state. Alteration of these non-GAP functions of eIF5 modulates the accuracy of AUG recognition in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strain constructions

To obtain strains PMY139 through PMY145, PMY03 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1Δ-63 his4-301(ACG) sui1Δ::hisG kanMX6:PGAL1-TIF11 p1200 [sc URA3 SUI1]) was cotransformed with plasmid pAS5-130 (sc TRP1 tif11-SE1*, SE2* + F131) and sc LEU2 plasmids harboring the appropriate SUI1 alleles on synthetic complete medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SC-Leu-Trp), and the resident SUI1+ URA3 plasmid (p1200) was evicted on 5-FOA medium.

Derivatives of strain JCY03 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1Δ-63 his4-301(ACG) sui1Δ::hisG p1200 [sc URA3 SUI1]) were constructed by transforming JCY03 to Leu+ with sc LEU2 plasmids harboring the appropriate SUI1 alleles (indicated in Table 1) on SC-Leu medium; p1200 was evicted by selecting for growth on 5-FOA medium.

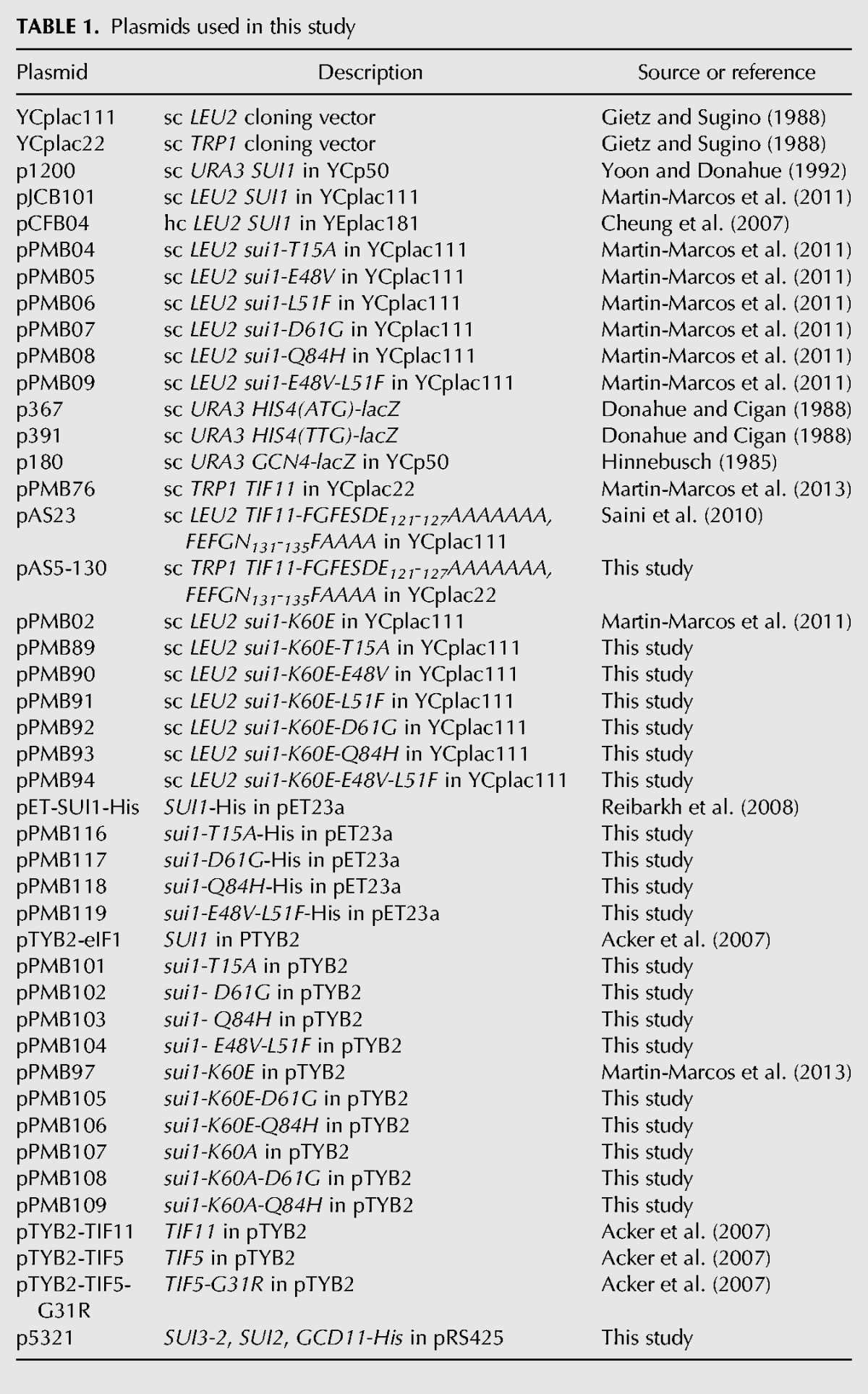

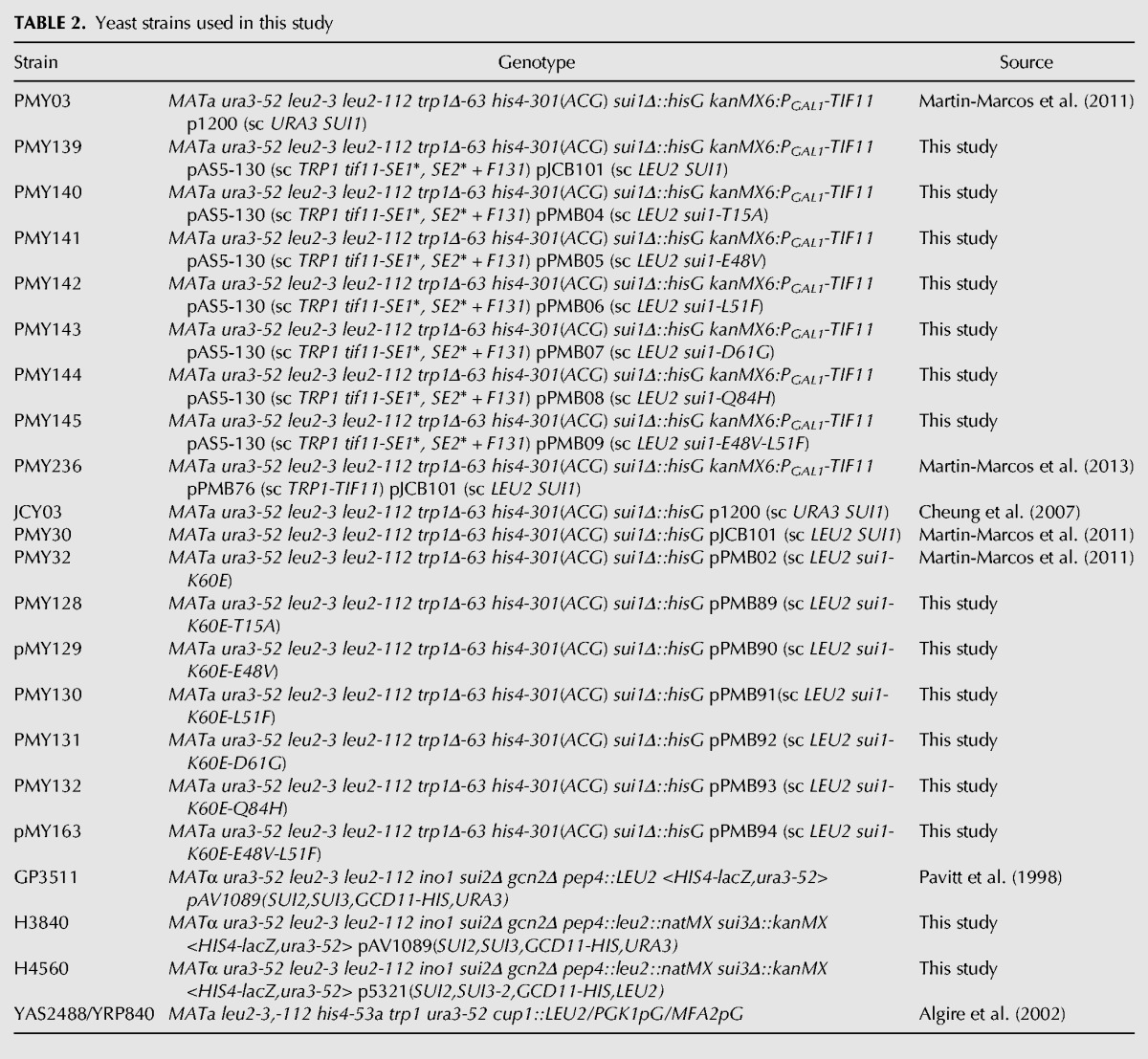

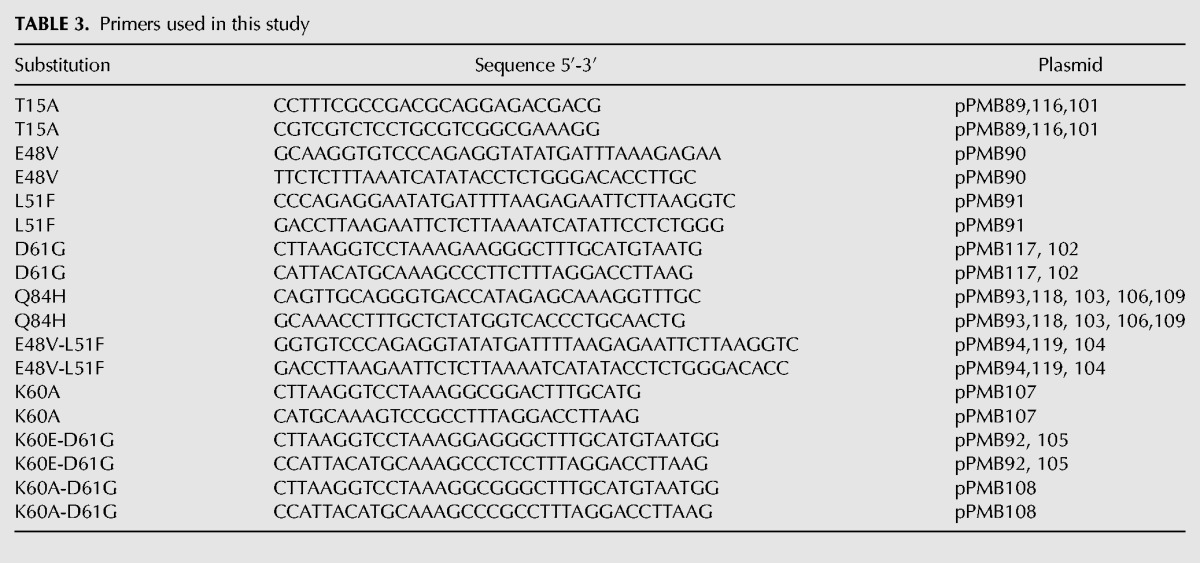

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

Strain H4560, used to purify the Sui3-2 variant of eIF2, was constructed from strain H3840 by plasmid shuffling (Guthrie and Fink 1991) to replace pAV1089 with p5321. H3840 was constructed from GP3511 by disrupting the LEU2 marker in the pep4::LEU2 allele with the natMX4 cassette in pAG25 (Goldstein and McCusker 1999) and replacing chromosomal SUI3 with the kanMX6 cassette in pFA6a-kanMX6 (Longtine et al. 1998) by one-step gene replacements.

Plasmid constructions

To generate the corresponding plasmids shown in Table 2, the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene) was employed with primers indicated in Table 3, using as templates plasmids pPMB02, pET-SUI1-His, pTYB2-eIF1, pPMB97, or pPMB107.

TABLE 2.

Yeast strains used in this study

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

For the construction of pAS5-130 (sc TRP1 tif11-SE1*, SE2* + F131), the 1142-bp fragment obtained from EcoRI/SalI-digested pAS23 was cloned in EcoRI/SalI site of YCplac22. Plasmid p5321, used for purifying the Sui3-2 variant of eIF2, was constructed by replacing the SmaI/XhoI fragment encoding SUI3 in pAV1726 (Gomez et al. 2002) with a mutagenized version of the same fragment encoding SUI3-2.

Biochemical assays

Assays of β-galactosidase activity in whole-cell extracts (WCEs) were performed as described previously (Moehle and Hinnebusch 1991). For Western analysis, WCEs were prepared by trichloroacetic acid extraction as previously described (Reid and Schatz 1982), and immunoblot analysis was conducted as previously described (Nanda et al. 2009) using antibodies against eIF1and eIF2Bε/Gcd6.

Biochemical assays in the reconstituted in vitro system

Buffers and reagents

The reaction buffer was composed of 30 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM potassium acetate (pH 7.4), 3 mM magnesium acetate, and 2 mM dithiothreitol. The composition of the enzyme buffer was 20 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM KOAc (pH 7.4), 2 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol.

Initiation factors eIF1, eIF1A, and eIF5 and mutant variants of these proteins were purified using the IMPACT system (NEB) as previously described (Acker et al. 2007) using the appropriate pTYB2-derived constructs. eIF1 WT and mutant proteins were labeled at their C termini with cysteine–lysine–fl dipeptide, using the expressed protein ligation system as previously described (Maag and Lorsch 2003). eIF1A was labeled at its C terminus with cysteine–lysine–tetramethylrhodamine dipeptide using the expressed protein ligation system as previously described (Maag and Lorsch 2003). His-tagged WT eIF2 or His-tagged eIF2 carrying the mutation S264Y in the β subunit (SUI3-2) was overexpressed in yeast using strains GP3511 and H4560, respectively, and purified as previously described (Acker et al. 2007). 40S subunits were purified as described previously from strain YAS2488 (Acker et al. 2007). The sequences of the model mRNAs were as follows: mRNA(AUG), 5′-GGAA[UC]7 UAUG[CU]10C-3′; mRNA(UUG), 5′-GGAA[UC]7UUUG[CU]10C-3′. Yeast initiator tRNA was synthesized from a hammerhead fusion template using T7 polymerase transcription and charged with [35S]-Met or with unlabeled methionine as previously described (Acker et al. 2007).

Fluorescence anisotropy experiments

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements of equilibrium binding constants (Kd) were performed as previously described (Maag and Lorsch 2003) using C-terminally fl-labeled eIF1 WT or mutant variants. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 497 nm and 520 nm, respectively. The data were fit with hyperbolic binding curves to determine Kd values (Maag and Lorsch 2003).

TC binding experiments

Measurement of the kinetics of TC binding to 40S•eIF1•eIF1A• mRNA complexes were carried out using a native gel-shift assay as previously described (Acker et al. 2007; Passmore et al. 2007; Kolitz et al. 2009). Component concentrations were 0.5–1 nM [35S]-Met-tRNAi, 1 mM GDPNP·Mg2+, 200 nM WT eIF2 or eIF2β-S264Y, 1 μM eIF1 (WT or mutant), 1 μM eIF1A, 5–40 nM 40S subunits, and 10 μM mRNA. Binding of labeled TC was stopped by adding a chase of excess (300-fold or more) unlabeled TC at different times. The observed rate constants (kobs) were determined at different 40S concentrations by fitting the data with a first-order exponential equation. The kobs values were plotted versus 40S concentrations and fit with a straight line to determine the slope, which corresponds to the association rate constant (kon).

To determine rate constants for TC dissociation from PICs, 43S•mRNA complexes were formed using [35S]-Met-tRNAi as described above. The concentration of eIF5 or eIF5-G31R, when present, was 1 μM. A chase of excess (300-fold or more) unlabeled TC was added, and the fraction of bound, labeled TC was monitored over time on native gels. Curves were fit with a single exponential equation to determine the dissociation rate constant (koff).

eIF1 dissociation kinetics

FRET experiments were carried out as previously described (Maag et al. 2005) using a SX.180MV-R stopped flow fluorometer (Applied Photophysics). 43S complex was made with 100 nM 40S subunits, 450 nM TC (1 mM GDPNP·Mg2+, 900 nM eIF2 or eIF2β-S264Y, 450 nM Met-tRNAi), 50 nM fl-labeled WT or mutant eIF1 (donor), 60 nM TAMRA-labeled eIF1A (acceptor), and 1 μM eIF5 or eIF5-G31R. This was mixed rapidly with an equal volume of 20 μM mRNA and 3 μM of unlabeled eIF1 as chase. Loss of FRET between the two factors was observed as an increase in fl fluorescence. The data were fit with a double exponential equation, with the first phase corresponding to a conformational change and the second to eIF1 dissociation.

Purification of eIF1 constructs and NMR experiments

NMR experiments were performed as described previously (Marintchev et al. 2007; Luna et al. 2012) 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker 500-MHz spectrometer. eIF1 WT or mutant proteins were overexpressed in Escherichia coli using minimal media (M9) containing 15N-labeled ammonium chloride. The cells were lysed, and the eIF1 proteins were purified via nickel affinity and gel filtration column chromatography. eIF1 protein samples for NMR measurements (1H-15N HSQC spectra) contained 200 μM protein in buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, and 10% D2O (pH 7.2). The backbone resonance assignments of yeast eIF1 were used to reference the 1H-15N HSQC spectra and confirm the location of the point mutants (Reibarkh et al. 2008).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tom Dever for many helpful suggestions during the course of this work. This study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH (P.M.M., A.G.H.) and by NIH grants GM62128 (J.R.L., which supported J.S.N. and J.R.L.) and CA068262 (G.W., which supported R.E.L.).

REFERENCES

- Acker MG, Kolitz SE, Mitchell SF, Nanda JS, Lorsch JR 2007. Reconstitution of yeast translation initiation. Methods Enzymol 430: 111–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algire MA, Maag D, Savio P, Acker MG, Tarun SZ Jr, Sachs AB, Asano K, Nielsen KH, Olsen DS, Phan L, et al. 2002. Development and characterization of a reconstituted yeast translation initiation system. RNA 8: 382–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano K, Clayton J, Shalev A, Hinnebusch AG 2000. A multifactor complex of eukaryotic initiation factors eIF1, eIF2, eIF3, eIF5, and initiator tRNAMet is an important translation initiation intermediate in vivo. Genes Dev 14: 2534–2546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke JD, LaCroute F, Fink GR 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet 197: 345–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung YN, Maag D, Mitchell SF, Fekete CA, Algire MA, Takacs JE, Shirokikh N, Pestova T, Lorsch JR, Hinnebusch AG 2007. Dissociation of eIF1 from the 40S ribosomal subunit is a key step in start codon selection in vivo. Genes Dev 21: 1217–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue TF, Cigan AM 1988. Genetic selection for mutations that reduce or abolish ribosomal recognition of the HIS4 translational initiator region. Mol Cell Biol 8: 2955–2963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Sugino A 1988. New yeast–Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking 6-bp restriction sites. Gene 74: 527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, McCusker JH 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15: 1541–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez E, Mohammad SS, Pavitt GD 2002. Characterization of the minimal catalytic domain within eIF2B: The guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for translation initiation. EMBO J 21: 5292–5301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C, Fink G 1991. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods Enzymol 194: 1–863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG 1985. A hierarchy of trans-acting factors modulate translation of an activator of amino acid biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 5: 2349–2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG 2005. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol 59: 407–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG 2011. Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75: 434–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG, Lorsch JR 2012. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation: New insights and challenges. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 4: a011544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Yoon H, Hannig EM, Donahue TF 1997. GTP hydrolysis controls stringent selection of the AUG start codon during translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 11: 2396–2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolitz SE, Takacs JE, Lorsch JR 2009. Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of the role of start codon/anticodon base pairing during eukaryotic translation initiation. RNA 15: 138–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin IB, Steitz TA 2013. The initiation of mammalian protein synthesis and mRNA scanning mechanism. Nature 500: 307–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A III, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna RE, Arthanari H, Hiraishi H, Nanda J, Martin-Marcos P, Markus MA, Akabayov B, Milbradt AG, Luna LE, Seo HC, et al. 2012. The C-terminal domain of eukaryotic initiation factor 5 promotes start codon recognition by its dynamic interplay with eIF1 and eIF2β. Cell Rep 1: 689–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag D, Lorsch JR 2003. Communication between eukaryotic translation initiation factors 1 and 1A on the yeast small ribosomal subunit. J Mol Biol 330: 917–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag D, Fekete CA, Gryczynski Z, Lorsch JR 2005. A conformational change in the eukaryotic translation preinitiation complex and release of eIF1 signal recognition of the start codon. Mol Cell 17: 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag D, Algire MA, Lorsch JR 2006. Communication between eukaryotic translation initiation factors 5 and 1A within the ribosomal pre-initiation complex plays a role in start site selection. J Mol Biol 356: 724–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marintchev A, Frueh D, Wagner G 2007. NMR methods for studying protein–protein interactions involved in translation initiation. Methods Enzymol 430: 283–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Marcos P, Cheung YN, Hinnebusch AG 2011. Functional elements in initiation factors 1, 1A and 2β discriminate against poor AUG context and non-AUG start codons. Mol Cell Biol 31: 4814–4831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Marcos P, Nanda J, Luna RE, Wagner G, Lorsch JR, Hinnebusch AG 2013. β-Hairpin loop of eIF1 mediates 40 S ribosome binding to regulate initiator tRNAMet recruitment and accuracy of AUG selection in vivo. J Biol Chem 288: 27546–27562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehle CM, Hinnebusch AG 1991. Association of RAP1 binding sites with stringent control of ribosomal protein gene transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 11: 2723–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda JS, Cheung YN, Takacs JE, Martin-Marcos P, Saini AK, Hinnebusch AG, Lorsch JR 2009. eIF1 controls multiple steps in start codon recognition during eukaryotic translation initiation. J Mol Biol 394: 268–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda JS, Saini AK, Munoz AM, Hinnebusch AG, Lorsch JR 2013. Coordinated movements of eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF1, eIF1A, and eIF5 trigger phosphate release from eIF2 in response to start codon recognition by the ribosomal preinitiation complex. J Biol Chem 288: 5316–5329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K, Meyer MR, Jackson BM, Slade D, Roberts C, Hinnebusch AG, Marton MJ 2001. Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4p is a master regulator of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 21: 4347–4368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore LA, Schmeing TM, Maag D, Applefield DJ, Acker MG, Algire MA, Lorsch JR, Ramakrishnan V 2007. The eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF1 and eIF1A induce an open conformation of the 40S ribosome. Mol Cell 26: 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavitt GD, Ramaiah KVA, Kimball SR, Hinnebusch AG 1998. eIF2 independently binds two distinct eIF2B subcomplexes that catalyze and regulate guanine–nucleotide exchange. Genes Dev 12: 514–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabl J, Leibundgut M, Ataide SF, Haag A, Ban N 2011. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic 40S ribosomal subunit in complex with initiation factor 1. Science 331: 730–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reibarkh M, Yamamoto Y, Singh CR, del Rio F, Fahmy A, Lee B, Luna RE, Ii M, Wagner G, Asano K 2008. Eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 1 carries two distinct eIF5-binding faces important for multifactor assembly and AUG selection. J Biol Chem 283: 1094–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GA, Schatz G 1982. Import of proteins into mitochondria. Yeast cells grown in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone accumulate massive amounts of some mitochondrial precursor polypeptides. J Biol Chem 257: 13056–13061 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini AK, Nanda JS, Lorsch JR, Hinnebusch AG 2010. Regulatory elements in eIF1A control the fidelity of start codon selection by modulating tRNAiMet binding to the ribosome. Genes Dev 24: 97–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh CR, He H, Ii M, Yamamoto Y, Asano K 2004. Efficient incorporation of eukaryotic initiation factor 1 into the multifactor complex is critical for formation of functional ribosomal preinitiation complexes in vivo. J Biol Chem 279: 31910–31920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valasek L, Nielsen KH, Zhang F, Fekete CA, Hinnebusch AG 2004. Interactions of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (eIF3) subunit NIP1/c with eIF1 and eIF5 promote preinitiation complex assembly and regulate start codon selection. Mol Cell Biol 24: 9437–9455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HJ, Donahue TF 1992. The sui1 suppressor locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a translation factor that functions during tRNAiMet recognition of the start codon. Mol Cell Biol 12: 248–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]