Abstract

Background:

In the recent decades increasing number of women have been seeking deaddiction services. Despite that the report data is very limited from India.

Objectives:

The present research aimed to study the demographic and clinical profile of women seeking deaddiction treatment at a tertiary care center in North India.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective structured chart review of 100 women substance abusers seeking treatment at a deaddiction center between September 1978 and December 2011.

Results:

A typical case was of 36.3 years age, married (65%), urban (61%), nuclear family (59%) based housewife (56%), with good to fair social support (69%). The commonest substance of abuse was tobacco (60%), followed by opioids (27%), alcohol (15%), and benzodiazepines (13%). The common reasons for initiation of substance use were to alleviate frustration or stress (49%) and curiosity (37%). Family history of drug dependence (43%), comorbidity (25%), and impairments in health (74%), family (57%), and social domains (56%) were common. Only a third of the sample paid one or more follow visit, and of those 58% were abstinent at the last follow-up. Significant predictors identified were being non-Hindu and higher educational years for abstinent status at follow-up.

Conclusion:

The common substances of abuse were tobacco, opioids, and alcohol and benzodiazepines; and family history of drug abuse and comorbidity were common. The follow-up and outcome were generally poor. This profile gives us some clues to address a hidden health problem of the community.

Keywords: Substance abuse, treatment seeking, treatment outcome predictors, women

For a number of reasons, among the substance abusers women comprise a unique clinical subpopulation. The social disadvantage and subordination of women on one hand and the rapid sociocultural and economic changes on the other, have significantly altered traditional structures and institutions within the society.[1] The pattern and degree of psychiatric comorbidity is different in women as compared to men.[2] Gender differences in the medical consequences of substance use have been highlighted,[3] with the females reporting higher physical and psychological impairment with an accelerated progression of alcoholism labeled as ‘telescoping’.[4,5,6]

Data on women substance users in India are scarce. In their ethnographic report, Ganguly et al.,[7] described female opium users in Rajasthan having been initiated into opium either by their husbands, or as medication for physical or mental ailments. Prevalence rates for substance use, abuse, and dependence have been remarkably lower among the women, with common substances of abuse being tobacco, followed by alcohol, opioids, and sedatives.[8] Use of cannabis and tranquilizers was reported to be low among women. While the urban women had generally quite low rates for the use of substances, among manual labor women as in tea plantations and paddy fields, tobacco consumption was equal to that among men.[9] Alcohol use disorders have been found to be less common in women as compared to men in the GENACIS study which studied a population of about 2,900 including about 1,500 females.[10] A study with 18 alcohol dependent women reported that compared to the initiation into alcohol coming through peers for men, it was through family members for women.[11] Also, compared to men, women became dependent on alcohol more rapidly, and had less of social and more of physical and psychiatric complications. A case-control study showed that children of women taking alcohol during pregnancy developed neurobehavioral disorder consistent with fetal alcohol syndrome.[12] A Rapid Assessment Survey (RAS) carried out at nine deaddiction centers across India reported 8.9% subjects as women; majority of these women were single or divorced, and reported physical and psychological problems, domestic violence, and guilt of neglecting their children.[13] Recent studies focusing on female sex workers from India have found substance use disorders in a large proportion and emphasized the need for treatment.[14,15]

A retrospective chart review of 35 women seeking treatment at our deaddiction center revealed the commonly abused substances as opioids, followed by alcohol, and tobacco and benzodiazepines, and that comorbid physical and psychiatric illnesses and impairments in multiple domains were common.[16] Substance use disorders have been found to be fairly prevalent in women in the community when absolute numbers are considered.[13] However, very few seek help from deaddiction services; at our center women patients constitute less than 1% of the service users.[17] One of the reasons could be disadvantages faced by women in health service access.[18]

As illustrated by this brief review of the literature, substance abuse leads to worse consequences in women. Hence, the importance of studying various aspects of substance abuse among women so as to evolve appropriate strategies to understand and manage the impact both from the individual as well as the gender perspective. In this context, the present research aimed to study the demographic and clinical characteristics of the women patients seeking treatment at a deaddiction center in northern India over a period of over 30 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at the Drug Deaddiction and Treatment Center (DDTC) of the Department of Psychiatry at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh; a tertiary-care hospital in north India that caters to more than 40 million people. Most patients come by self or family referral, whereas others are referred from other hospitals or other departments of PGIMER. The services of the center include outpatient, inpatient, laboratory, aftercare, and liaison with other governmental and nongovernmental agencies, and self-help groups. These services are provided by a team of psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, psychologists, and other support workers.

The study covered women patients registered at the DDTC between September 1978 (when the Department of Psychiatry started a dedicated substance abuse outpatient service) and December 2011. The diagnosis of substance dependence was made by a consultant psychiatrist after direct interview with the patient and the relatives. The diagnoses were made according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/-10[19,20] before/after December 1992. Detailed evaluation was followed by management including detoxification, symptomatic treatment, treatment of associated medical and psychiatric conditions, and psychosocial counseling of patients and their families. Regular follow-ups were done by a psychiatrist, and if need be social workers, when patients’ drug use profile, social, and occupational functioning, and physical and psychological problems were monitored and documented.

For all the 100 registered female subjects the available records were scanned and relevant information was retrieved according to a study specific predetermined coding plan. The information included sociodemographic profile, substance use pattern, physical and psychiatric comorbidities, impairment in different areas of functioning, and follow-up data. The clinical information was discerned from the recorded history, clinical evaluation, and follow-up notes.

An earlier publication[16] from our center has reported data on 35 patients registered between 1978 and 2003. For the sake of reporting complete data over the almost entire period spanning the existence of the center (1978-2011) we decided to incorporate those 35 patients in our total sample. Thus, analysis and interpretation were redone over the total sample of 100 cases.

Measures

Sociodemographic profile proforma

A semistructured proforma was used to record age, marital status, educational years, occupation, family type, religion, and locality. Social support was measured on a 4-point scale measuring poor (no support system), minimal (support from only one source; family, network, or society), fair (support from two sources), or good social support (support from multiple sources).[16]

Clinical profile proforma

This included details of substances, duration of dependence, and physical and psychiatric comorbidity. The information about the physical and psychiatric comorbidity was inferred from the history, clinical, and laboratory evaluation and monitoring of the patient throughout the contact period.

Impairment in various areas of functioning

Four levels of drug-related complications were operationalized which covered the seven areas of functioning such as health, occupation, finance, family, marital, legal, and social areas.[21] The severity of complications at the first presentation (nil, mild, moderate, and severe) was extracted from the case records.

Follow-up details

Abstinence, relapsed, or unchanged was considered as the primary outcome measure. Abstinence was defined as no substance intake. Relapse was defined as reemergence of substance dependence as per the ICD-9/-10.[19,20] The duration of follow-up was calculated as number of months from first visit to the last visit to the hospital.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was used for the demographic and clinical variables. Nonparametric tests were applied to see relationship between nominal and ordinal data. Parametric tests were applied for the continuous variables. Simple binary logistic regression analysis with enter method was used to study the relationship among independent variables which were more frequently present in subjects who followed-up and who remained abstinent (improved) at follow-up. Analysis was done by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14 for Windows (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

Demographic profile

The mean age of the sample was 36.33 years (standard deviation (SD): 11.87 years; range: 12-63 years), with age of onset of substance intake of 27.30 years (SD: 10.02 years), and age of onset of substance dependence of 29.21 years (SD: 9.87 years). The mean duration of substance dependence was 7.10 years (SD: 7.24 years; median: 5 years). The mean years of education were 7.75 (SD: 5.73 years; range: 0-17 years). Majority were married (65%), non-earning (72%; includes 56% housewives), Hindu by religion (63%; 32% were Sikh and 5% others), from urban locality (61%), and nuclear family (59%). Majority was having fair/good social support (69%) and family history of substance dependence was present in nearly half of the subjects (43%).

Clinical profile

The common substances were: Tobacco (60%), opioids (27%), alcohol (15%), and sedatives (13%). Tobacco was used by smoking, chewing, or both (28, 27, and 5%, respectively). The common opioids used were: Injectable buprenorphine or pentazocine (14%), dextropropoxyphene (8%), heroine (4%), and opium or poppy husk (2%). The reasons for initiating substance use were: To alleviate frustration or stress (49%), curiosity (37%), and peer pressure (14%).

Comorbid psychiatric disorder (other than substance dependence), present in 25% cases, included: Depressive disorder (moderate depression or dysthymia; 12%), adjustment disorder (5%), somatoform disorder (3%), anxiety disorder and schizophrenia (2% each), and obsessive compulsive disorder and bipolar affective disorder (1% each).

Physical comorbid disorder was present in 22% cases. The common disorders were: Migraine headache (4%), alcoholic liver disease and menorrhagia (3% each), hypertension and renal stone (2% each), and seizure disorder, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cholecystitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, chronic suppurative otitis media, hydronephrosis, hypothyroidism, psoriasis, prolapse intervertebral disc, subarchnoid hemorrhage, and fibroid uterus (1% each).

Drug-related impairments

The most affected domains were of health (74%), family (57%), and social life (56%). The least impairment was reported in the legal domain (1%). Other less affected domains were of financial (43%), occupational (42%), and marital life (33%). Mean total score was 3.70 (range 0-18).

Treatment and outcome details

More than one-third subjects were detoxified with clonidine for opioids (24 cases) or oral lorazepam/chlordiazepoxide for alcohol (13 cases). Pharmacoprophylaxis was given to only five subjects: Naltrexone (three cases), and baclofen (two cases). Other additional psychotropics were given to 14 cases (escitalopram-five cases; imipramine - three cases; and fluoxetine, duloxetine, mirtazapine, venlafaxine, olanzapine, and risperidone-1 case each).

As 69 cases never followed-up, follow-up data were available only for 31 cases. The duration of follow-up ranged 0.5-72 months with a mean of 5.01 months (median 2 months). The number of follow-ups ranged 1-30 with a mean of 3.96 (median 3) follow-ups. Of those who did follow-up, 58.06% were recorded as ‘improved’.

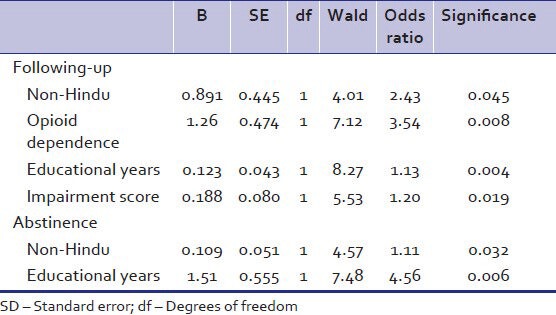

Subjects who followed-up were more commonly non-Hindus (43.2 vs 23.8% Hindus, χ2 = 4.11, P = 0.042), dependent on opioids (χ2 = 7.51, P = 0.006), with higher years of education (10.29 vs 6.60 years, t = −3.09, P = 0.003), and higher impairment score (4.80 vs 3.20, t = −2.57, P = 0.011). The lowest follow-ups were in cases with tobacco dependence (13.33%, χ2 = 21.88, P < 0.001).

Subjects with improved/abstinent status at last follow-up were again more commonly non-Hindus (32.4 vs 9.5% Hindus, χ2 = 8.28, P = 0.004) and with higher years of education (10.44 vs 7.15 years, t = −2.24, P = 0.027).

Predictors of follow-up and abstinence

As shown in Table 1, significant predictors for follow-up were being non Hindu, opioid dependence, educational years, and impairment score; the odds ratio was highest for opioid dependence. Similarly significant predictors for abstinence at last follow-up were being non Hindu, and educational years; the odds ratio was highest for educational years.

Table 1.

Simple binary logistic regression analysis showing predictors of following-up and abstinence

DISCUSSION

Indian society is in transition and there are problems with changing roles and lifestyles. Even then, compared to the West the problem of substance abuse among women is very low. However, it is being increasingly recognized among the related professionals and the media that the prevalence of substance abuse among women is showing a definite increase. As yet, this does not get reflected in official statistics for a variety of reasons: Lack of funding and independent financial resources, societal stigma, and burden of childcare, problems in transportation, and the largely subordinate position of the women.[22]

The present research was a retrospective chart review with the aim of studying the profile of women seeking treatment at a deaddiction center at a tertiary care hospital. Thus, it attempts to provide descriptive information about substances abuse among women in northern India. This profile of treatment seekers may help us to address more effectively a partly hidden problem.

Compared to an earlier study from our center,[16] our sample was larger (100 vs 35 subjects), with higher drug abuse in family members (43 vs 20%) and shorter duration of follow-up (5 vs 8 months). The commonest substance of abuse recorded was tobacco in our study compared to opioids in the earlier work. Similar to that study[16] more than half of our study subjects abstaining from the substances at last follow-up signify the importance of appropriate treatment and compliance in this subgroup. Another study,[23] also reported better outcome in women than men, despite differences in populations targeted, type of treatment, problem drug, and treatment setting.

We found more follow-ups for non-Hindu subjects, opioid dependence, higher education, and greater impairment and least follow-ups for nicotine dependence. Similar to an earlier study[24] our subjects with higher years of education were significantly more abstinent at the last follow-up. In our study, significant predictors of follow-up were non-Hindu subject, opioid dependence, educational years, and impairment score, and predictors for remaining abstinent at last follow-up were non-Hindu subject and educational years.

Majority of the 100 women in the present study being single, well-educated and in their 4th decade is similar to the finding of the Rapid Assessment Survey.[13] Nearly half of our sample having initiated substance use to alleviate frustration or stress is in line with earlier report of humiliation, shame, anger, and marital conflict as major reasons to initiate drugs.[22]

The substances of abuse being mainly tobacco and opioids, and less commonly sedative-hypnotics and alcohol, is similar to earlier studies from other parts of India reporting no abuse of cannabis or inhalants among women.[10,12] Nearly half of our sample having a family history of substance dependence is supportive of earlier research establishing that family members’, especially husband's and father's, substance abuse plays a contributory role in initiation of substance use in women.[25]

It is well-recognized that women have proportionately more fatty tissue, less body water, and lesser activity of gastric alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme than men, leading to higher drug concentration and related complications.[22] In keeping with this, the physical and psychiatric comorbidity was quite prevalent in our sample as has also been reported by other studies from India[11,16] and the West.[4,26,27] Also, our sample reporting health as the most affected area, alongside a longer duration of substance dependence and more impairment in family rather than financial or occupational domains is similar to the findings of another report from India.[11]

We found affective disorders as the most common psychiatric comorbidity. This finding is consistent with the literature from the West[2,28,29] and India[16] reporting a higher psychiatric comorbidity in women substance abusers. A more recent study reported older women to have relatively less severe substance abuse and better social networking and treatment outcome compared to younger women.[30]

The results of our study must be seen within its limitations. The sample size was small. The retrospective chart review entailed inferring relevant data from the recorded narratives. Some of the instruments, assessments, and definitions used (e.g., social support, impairment, and outcome) were center-specific and have not been evaluated for their reliability. The sample comprised of women seeking deaddiction treatment at one center. Hence, generalization of our findings to other deaddiction centers, and across the community and the country demands caution.

However, within these limitations the study leads to the following conclusions. A typical woman seeking treatment for substance abuse was a middle-aged, married, school drop-out, and house-wife from an urban nuclear family with substance abuse impacting their lives, especially their physical health. Thus there is a need for measures to improve access to deaddiction services to women substance users in the community. This may well be a small part of the wider concerted social action in the context of empowerment, support, and attention to the special needs of women.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs CS, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Giovannucci EL, Manson JE, Kawachi I, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1245–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505113321901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson PB, Richter L, Kleber HD, McLellan AT, Carise D. Telescoping of drinking-related behaviors: Gender, racial/ethnic, and age comparisons. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1139–51. doi: 10.1081/JA-200042281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piazza NJ, Vrbka JL, Yeager RD. Telescoping of alcoholism in women alcoholics. Int J Addict. 1989;24:19–28. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR. Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganguly KK, Sharma HK, Krishnamachari KA. An ethnographic account of opium consumers of Rajasthan (India): Socio-medical perspective. Addiction. 1995;90:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan D, Sundaram KR, Sharma HK. A study of drug abuse in rural areas of Punjab (India) Drug Alcohol Depend. 1986;17:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(86)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohan D, Sundaram H. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1983. A collaborative study on non-medical use of drugs in the community. Base line survey report. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benegal V. India: Alcohol and public health. Addiction. 2005;100:1051–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvaraj V, Suveera P, Ashok MV, Appaya MP. Women alcoholics: Are they different from men alcoholics ? Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:288–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nayak R, Murthy P, Girimaji S, Navaneetham J. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: A case-control study from India. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58:19–24. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Study of substance abuse in women. In: Women and drug abuse in India: The problem in India. Ministry of Social Justice end Empowerment, Government of India and the United Nations International Drug Control Programme, Regional Office for South Asia (UNDCP-ROSA) 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowen KJ, Dzuvichu B, Rungsung R, Devine AE, Hocking J, Kermode M. Life circumstances of women entering sex work in Nagaland, India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011;23:843–51. doi: 10.1177/1010539509355190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kermode M, Songput CH, Sono CZ, Jamir TN, Devine A. Meeting the needs of women who use drugs and alcohol in North-east India–a challenge for HIV prevention services. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:825. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grover S, Irpati AS, Saluja BS, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Substance-dependent women attending a de-addiction center in North India: Sociodemographic and clinical profile. Indian J Med Sci. 2005;59:283–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu D, Aggarwal M, Das PP, Mattoo SK, Kulhara P, Varma VK. Changing pattern of substance abuse in patients attending a de-addiction centre in north India (1978-2008) Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:830–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fikree FF, Pasha O. Role of gender in health disparity: The South Asian context. BMJ. 2004;328:823–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1979. The ICD-9 Classification of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu D, Jhirwal OP, Mattoo SK. Clinical characterization of use of acamprosate and naltrexone: Data from an addiction center in India. Am J Addict. 2005;14:381–95. doi: 10.1080/10550490591006933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22:241–52. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hser YI, Evans E, Huang YC. Treatment outcomes among women and men methamphetamine abusers in California. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenfield SF, Sugarman DE, Muenz LR, Patterson MD, He DY, Weiss RD. The relationship between educational attainment and relapse among alcohol-dependent men and women: A prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1278–85. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080669.20979.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvanzo AA, Storr CL, La Flair L, Green KM, Wagner FA, Crum RM. Race/ethnicity and sex differences in progression from drinking initiation to the development of alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ceylan-Isik AF, McBride SM, Ren J. Sex difference in alcoholism: Who is at a greater risk for development of alcoholic complication? Life Sci. 2010;87:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hvidtfeldt UA, Frederiksen ME, Thygesen LC, Kamper-Jørgensen M, Becker U, Grønbaek M. Incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease in Danish men and women with a prolonged heavy alcohol intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1920–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Otaiba Z, Epstein EE, McCrady B, Cook S. Age-based differences in treatment outcome among alcohol-dependent women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:423–31. doi: 10.1037/a0027383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]