Abstract

Background:

The business process outsourcing (BPO) sector is a contemporary work setting in India, with a large and relatively young workforce. There is concern that the demands of the work environment may contribute to stress levels and psychological vulnerability among employees as well as to high attrition levels.

Materials and Methods:

As part of a larger study, questionnaires were used to assess psychological distress, burnout, and coping strategies in a sample of 1,209 employees of a BPO organization.

Results:

The analysis indicated that 38% of the sample had significant psychological distress on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28; Goldberg and Hillier, 1979). The vulnerable groups were women, permanent employees, data processors, and those employed for 6 months or longer. The reported levels of burnout were low and the employees reported a fairly large repertoire of coping behaviors.

Conclusions:

The study has implications for individual and systemic efforts at employee stress management and workplace prevention approaches. The results point to the emerging and growing role of mental health professionals in the corporate sector.

Keywords: Burnout, business process outsourcing, coping, India, psychological distress, stress

The business process outsourcing (BPO) sector is often called the ‘Sunshine Sector’ in India. This contemporary work setting provides job opportunities for youth and promotes economic growth. It also brings unique challenges with its nontraditional work processes, including electronic performance and monitoring, lack of face to face customer-employee interaction, and extended technology interface. The added pressures of ‘emotional labor’[1] on employees to regulate negative emotions during customer interactions, are integral aspects of the work environment.

There are concerns about the psychological vulnerability to stress and burnout in this work environment.[2,3,4,5,6] High attrition rates, absenteeism, and occupational diseases are concerns for organizations in India as well[7] and suggest the need to look more closely at psychosocial factors among employees. Another review suggested that women may form a particularly vulnerable section of the call center workforce in our country.[8]

Empirical research on work stress, health issues, and burnout[9] among employees from this industry in India has been limited.[10,11,12,13] Studies have typically involved relatively small samples and specific assessment tools developed for the study. The possible role of culture-specific mechanisms operating as a stress buffer in the collectivist Indian scenario has been discussed.[13]

In this context, the present study was planned in response to a large BPO company's human resource (HR) management employee well-being initiative. The objectives were to explore employee experiences of stress and psychological distress, using an exploratory mixed-method design, and to translate the findings into practical strategies for organizational changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample consisted of 1,500 employees of a BPO company in Bangalore. The sample comprised 47.1% of the total workforce and represented all levels of employment. The questionnaires assessing sociodemographic data, psychological distress, occupational stress, burnout, job satisfaction, psychological well-being, and coping were administered in groups and the participants were provided sealed envelopes for return to the research team. A total of 1,209 questionnaires were received, which represents a response rate of 80.6%. The results related to sociodemographic information, psychological distress, burnout, and coping are presented in this paper. Ethical concerns regarding anonymity, confidentiality, and informed consent were adhered to. Information about help - seeking options and access to mental health consultations was provided to all employees.

Tools

Sociodemographic datasheet

The sociodemographic datasheet, developed for the research study, elicited relevant information such as age, sex, marital status, domicile, living arrangement, and employment details.

General health questionnaire

The GHQ[14] is used to detect psychological distress and vulnerability to psychiatric disorder in the general population and within community or nonpsychiatric clinical settings. In the GHQ-28, the respondent is asked to compare one's recent psychological state with his or her usual state. The four subscales derived through factor analysis; somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression; have a 4 point scoring system using GHQ scoring (0-0-1-1). The total of all the subscale scores gives information about the present mental status and the cutoff of 5 was taken to identify at-risk individuals experiencing psychological distress. The GHQ has well-established reliability and validity and high sensitivity and specificity. It has been widely used in the Indian setting for both case identification and as an indicator of psychological distress.[14]

Maslach burnout inventory - General survey

This 16-item tool[15] assesses respondents’ relationship with their work on a continuum from engagement to burnout. Items are scored on a 7 point rating scale with fixed anchors that range from never (0) to everyday (6). A high score on burnout is reflected in high scores on emotional exhaustion (EX) and cynicism (CY) subscale and low score on professional efficacy (PE). An average degree of burnout is reflected in average scores on the three subscales. A low degree of burnout is reflected in low scores on the EX and CY subscales and high scores on the PE subscale. Studies have supported the invariance of the factor structure across various occupational groups[16] and various countries.[17]

The coping checklist

The coping checklist[18] was developed in India and consists of 70 items describing a broad range of behavioral and cognitive and emotional responses that an individual might use to handle stress. The checklist is open-ended which allows the individual to report any additional coping behavior. Items are scored dichotomously in a Yes/No format indicating the presence/absence of a particular coping behavior. There are seven subscales: Problem solving, denial, positive distraction, negative distraction, acceptance, religion/faith, and social support seeking. The test-retest reliability for a 1 month period was reported as 0.74 and the internal consistency for the full scale as 0.86. It has been used in India with a variety of populations.

Analysis of data

Frequencies, percentages, Pearson product-moment correlations, and student's t-tests were computed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 10).

RESULTS

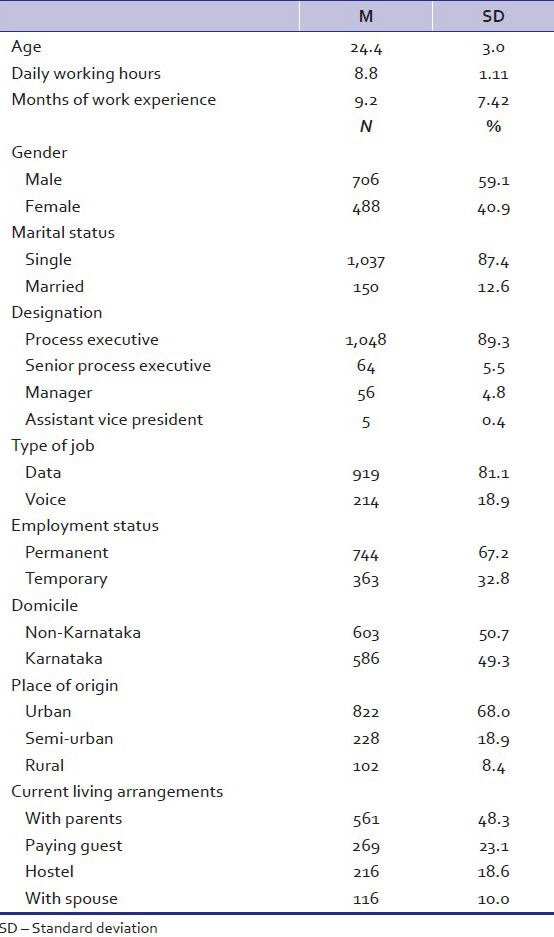

Table 1 indicates that the sample was predominantly from an urban area, with a male preponderance and largely single with an average age of 24.4 years. A large percentage lived with their parents. There was almost equal representation in terms of domicile within Karnataka and outside the state. Over one-third of the respondents were permanent employees of the organization. The majority were involved in data jobs (81.1%), while voice work was a much smaller percentage. The average daily working hours reported were 8.8 hrs? (standard deviation (SD) = 1.11). The sample had an average work experience of 9.22 months at the organization. Almost half (48.5%) of the employees had been in the present job for a period of 6 months or less; 27% for a period between 6 months and a year; 17.3% for 1-2 years, and 7.2% for 2 years and above.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the employees from a business process outsourcing company (N=1,209)

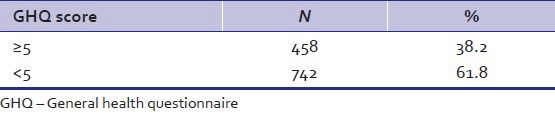

Table 2 describes the percentage of employees found to have psychological distress based on the GHQ scores.

Table 2.

Psychological distress among the employees from a business process outsourcing company (N=1,209)

The results indicate psychological distress among 38.2% in the sample of employees. The most frequently reported symptoms were in the categories of somatic symptoms as well as anxiety and insomnia. Further analysis indicated that the groups who were more vulnerable were females (P < 0.05), permanent employees (P < 0.01), data processors (P < 0.01), and those employed for 6 months or longer in the company (P < 0.01). Marital status or domicile was not significantly correlated with levels of psychological distress on the GHQ.

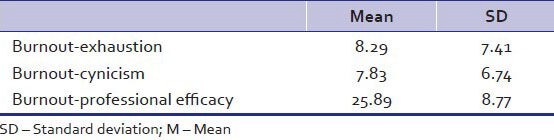

The results in Table 3 indicate low levels of burnout, in view of low levels of exhaustion and cynicism, with high levels of professional efficacy.

Table 3.

Burnout among the employees from a business process outsourcing company (N=1,209)

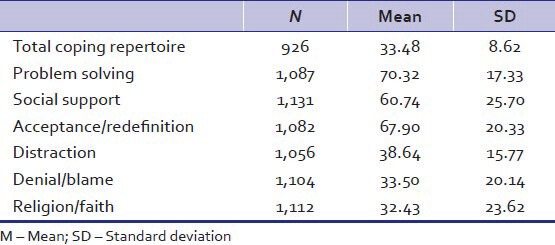

The results in Table 4 indicate a fairly large coping repertoire with a mean of 33 coping strategies (SD = 8.62), out of a possible 70 commonly used strategies. This is indicative of the number of coping methods the individuals have at their disposal when faced with stress. This group has a fairly large repertoire of coping behaviors at their disposal. They primarily use a combination of problem focused coping, acceptance-redefinition based coping, and social support seeking behaviors.

Table 4.

Coping behavior among the employees from a business process outsourcing company (N=1,209)

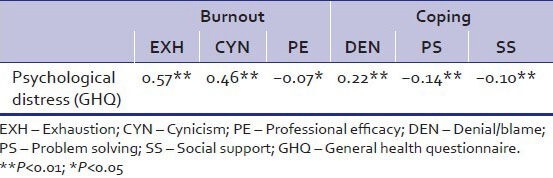

Table 5 illustrates that higher levels of emotional and psychological distress were significantly associated with lower levels of professional efficacy and less frequent use of problem-solving strategies and social support coping mechanisms. Higher scores on the GHQ were also associated with higher levels of burnout in terms of exhaustion and cynicism and increased use of denial and blame as coping mechanisms.

Table 5.

Correlation between psychological distress and the dimensions of burnout and coping among the employees from a business process outsourcing company (N=1,209)

DISCUSSION

The high rates of psychological distress, among 38.2% of the employees are noteworthy. The figures are comparable with those from a study with 2,074 call center employees in France,[19] which reported that 36% showed moderate or high levels of psychological distress, using the GHQ-12. A marginally higher percentage of 39% was found in a postal survey of employees from 36 British call centers using the GHQ-12.[20] A study on a small sample of employees from Indian Information Technology and Information Technology Enabled Services (IT/ITES) sectors, reported a slightly higher rate of 38%, using the GHQ-28, albeit with a lower cutoff score.[11] Clearly, call center employees form a high risk group for psychological distress. A large study of a heterogeneous working population in the Netherlands reported an overall rate of psychological distress as 22%.[21] Other vulnerable employee groups identified in research include factory workers, with rates ranging from 33.5-39%.[22,23]

The present findings pointing to a relatively high rate of psychological distress (38.2%) among BPO employees can be viewed in relation to typical rates found in community samples using the GHQ. Diverse results from community surveys indicate rates of 16.6% in Singapore,[24] 25.7% in the UK[25] -33.7% in Iran.[26]

Worryingly, 12.1% of employees who participated in the study reported taking sleeping pills several times a month and 20% reported use of anxiolytics or antidepressants in the last year. Of the four GHQ subscales, higher scores were in areas of somatic symptoms and anxiety and insomnia suggesting the impact of the nature of work involving shift work and accompanying disturbance in circadian rhythms. Although the depression subscale scores were not high, the elevated scores in other domains indicate vulnerability to continued psychological symptoms and morbidity.

The results highlight that women in the BPO sector are more vulnerable to experiencing psychological distress and adds credence to earlier reports from India.[5,8] The national report on call centers by the V. V. Giri National Labor Institute[5] reported that there were more males than females in the workforce. They also found that the high attrition rate among women could be attributed to the inconvenient shift system, limited career prospects, and increased work stress. In another study,[27] the higher stress among women BPO employees was attributed to the dual role stress with accountability both at home and at office, prolonged night shifts with associated social pressures and safety concerns, gender discrimination, and the glass ceiling. They suggested the need for HR development practices; for example, mentoring, secure transport systems, and family friendly policies; focused on specifically reducing stress for women and making work environments more gender inclusive. These findings buttress the need for gender-sensitive management initiatives.

Interestingly, the burnout rates are not very high and on first glance do not match with the relatively high rates of psychological distress. However, burnout is defined as related to chronic stress when demands at the workplace are taxing or exceeding individual resources over a long period of time. The workforce in the present study was largely in the initial stage of their employment, with 75.5% working in the organization for less than 1 year. Burnout can be a gradual process with varied psychosomatic and physical symptoms as part of the manifestation. The sleep disturbances, anxiety, and somatic symptoms captured by the GHQ, could well reflect the initial warning signs of psychological distress, which can potentially culminate in burnout. The results imply the need for preemptive action to make changes at the individual and organizational level.

Contemporary writings about burnout have emphasized the role of individual and organizational factors, and their fit, in determining the vulnerability to burnout. One of the protective individual factors is the ability to cope with workplace challenges.[28] It is possible that the use of a large coping repertoire and frequent use of adaptive coping mechanisms have been beneficial to this group. Problem solving, acceptance/redefinition coping (coming to terms with the problem), and social support (which has components of both problem and emotion focused coping) are associated with lower feelings of exhaustion and cynicism and a greater perception of professional efficacy and lower psychological distress. The use of denial/blame coping is associated with higher levels of psychological distress in this sample. This finding corroborates earlier evidence, which has found avoidance and escape forms of coping such as denial/blame to be related to dysphoria and future diagnosis of depression.[29,30]

These findings can guide the use of mental health interventions in the work setting. The goal of improving adaptive coping and minimizing the use of coping strategies associated with negative outcomes can be addressed with methods such as stress inoculation training, relaxation techniques, and sleep hygiene methods.

The study had some limitations which can inform future research in this area in India. The sample size was large, but was drawn from only one BPO organization. The generalizability of results could be increased with a sample drawn from different organizations, reflecting varied aspects of the work environment, and employee characteristics. The addition of control groups from the general population and from other professional sectors would enable a comparative understanding of the rates of psychological distress. Future studies focused on burnout and levels of psychological distress could evaluate other variables that reflect salient organizational aspects of this work. Statistical methods like multiple regression analysis could help identify individual and organizational predictors of burnout and psychological distress and point to specific areas for change. The inclusion of employees with a longer duration of work in the BPO sector would be important as burnout usually develops over an extended period of time. Indian studies could also assess the utility of an employee burnout scale developed and validated with customer service representatives in India.[31]

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the study can be translated into practical recommendations for the BPO sector. The study reveals worrying high figures for psychological distress among the employees. Attention to the employee psychological health should be an integral aspect of organizational commitment to its workforce. Counseling services (ideally a 24 hour service) should be available for both workplace and non-workplace related stress (e.g., bereavement and marital discord). Referral networks are essential and some nodal points could be the team leaders and the health center.

Although, the intrinsic nature of the BPO job cannot be changed, various organizational and HR practices can be modified based on the research findings in this area. Specific recommendations for HR involvement practices like training, participation, and performance related pay, have been listed,[32] aimed at reducing burnout. Organizations in India need to evaluate levels of occupational stress and psychological distress among their employees and prioritize appropriate changes.

Clearly, new roles are emerging for clinical psychologists in the context of the current zeitgeist. Both psychologists and HR development professionals have distinct contributions to make. This new avatar of “corporate psychologist” in India calls for specific training for this emerging role. This presents opportunities for the growth of consulting organizations with psychologists as key resource persons. Techno savvy interventions; for example, internet-based services and teleconsultations, must be integrated with more conventional mental health interventions. The development of focused modules reflecting sociocultural changes would be critical for the needs of this young work force. Hidden drug and alcohol problems in the BPO sector are highlighted in media reports and should be a context for assessment, prevention, and treatment. Interventions at both individual and systemic levels, focused on optimizing adaptive methods of coping, will help address stress, burnout, and psychological well-being.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The study was invited and funded by a leading business process outsourcing organization in Bangalore as part of their human resource management initiative for employee wellbeing

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hochschild A. California, USA: University of California Press; 1983. The managed heart: Commercialization of human feelings. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dataquest IDC E-SAT Survey. 2005. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.dqindia.com/dataquest/news/146982/e-sat-survey-2005-the-burnout-syndrome .

- 3.Healy J, Bramble T. Dial ‘B’ for Burnout? The experience of job burnout in a telephone call centre. Labour Ind. 2003;14:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houlihan M. Eyes wide shut? Querying the depth of call centre learning. J Eur Ind Train. 2000;24:228–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramesh BP. Noida: VV Giri National Labour Institute; 2004. Labour in business process outsourcing: A case study of call centre agents. NLI Research Studies Series No. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viser WA, Rothmann S. Exploring antecedents and consequences of burnout in a call centre. SA J Ind Psychol. 2008;34:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesavachandran C, Rastogi SK, Das M, Khan AM. Working conditions and health among employees at information technology-enabled services: A review of current evidence. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:300–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh P, Pandey A. Women in call centers. Econ Polit Wkly. 2005;40:684–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maslach C. Burned-out. Hum Relat. 1976;15:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhuyar P, Banerjee A, Pandve H, Padmanabhan P, Patil A, Duggirala S, et al. Mental, physical and social health problems of call centre workers. Ind Psychiat J. 2008;17:21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaturvedi SK, Kalyanasundaram S, Jagadish A, Prabhu V, Narasimha V. Detection of stress, anxiety and depression in IT/ITES professionals in the Silicon Valley of India: A preliminary study. Prim Care Comm Psychiatr. 2007;12:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suri S, Rizvi S. Mental health and stress among call centre employees. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2008;34:215–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surana S, Singh AK. The effect of emotional labour on job burnout among call-centre customer service representatives in India. Int J Work Organ Emot. 2009;3:18–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9:139–45. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE. The MBI general survey. In: Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, editors. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB. Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1996;9:229–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schutte N, Toppinen S, Kalimo R, Schaufeli W. The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations. J Occ Org Psychol. 2000;73:53–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao K, Subbakrishna DK, Prabhu GG. Development of a coping checklist: A preliminary report. Indian J Psychiat. 1989;31:129–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charbotel B, Croidieu S, Vohito M, Guerin A, Renaud L, Jaussaud I, et al. Working conditions in call center, the impact on employee health: A transversal study. Part II. Int Arch Occ Environ Health. 2009;82:747–56. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0351-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health and Safety Executive. Psychological risk factors in call centres: An evaluation of work design and well-being. Research Report no 169. 2003. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr.169.pdf .

- 21.Bultmann U, Kant I, Kasl SV, Beurskens AJHM, van den Brandt PA. Fatigue and psychological distress in the working population: Psychometrics, prevalence, and correlates. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:445–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janyam K. The influence of job satisfaction on mental health of factory workers. Internet J Ment Health. 2011:7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanbhag D, Joseph B. Mental health status of female workers in private apparel manufacturing industry in Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int J Collab Res Internal Med Pub Health. 2012;4:1893–900. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fones CS, Kua EH, Ng TP, Ko SM. Studying the mental health of a nation: A preliminary report on a population survey in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 1998;39:251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bebbington PE, Marsden L, Brewin CR. The need for psychiatric treatment in the general population: The Camberwell needs for care survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:821–34. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmadvand A, Sepehrmanesh Z, Ghoreishi FS, Afshinmajd S. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the general population of Kashan, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pathak S, Sarin A. Management of stress among women employees in BPO industry in India. Int J Manage Bus Stud. 2011;1:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Fiske ST, Schacter DL, Zahn-Waxler C, editors. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Tilson M, Seeley JR. Dimensionality of coping and its relation to depression. J Per Soc Psychol. 1990;58:499–511. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moeller DM, Richards SC, Hooker K, Ursino AA. Gender differences in the effectiveness of coping with dysphoria: A longitudinal study. Counse Psychol Quart. 1992;5:349–57. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Surana S, Singh AK. Development and validation of job burnout scale in the Indian context. Int J Soc Syst Sci. 2009;1:351–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castanheira F, Chambel MJ. Reducing burnout in call centers through HR practices. Hum Resour Manage. 2012;49:1047–65. [Google Scholar]