Abstract

Context:

Depression affects about 20% of women during their lifetime, with pregnancy being a period of high vulnerability. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy ranges from 4% to 20%. Several risk factors predispose to depression during pregnancy including obstetric factors. Depression during pregnancy is not only the strongest risk factor for post-natal depression but also leads to adverse obstetric outcomes.

Aims:

To study the prevalence of depression during pregnancy and its associated obstetric risk factors among pregnant women attending routine antenatal checkup.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional observational survey done at the outpatient department (OPD) of the department of obstetrics of a tertiary care hospital in Navi Mumbai.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and eighty-five pregnant women were randomly administered the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) for detecting depression. Additional socio-demographic and obstetric history was recorded and analyzed.

Results:

Prevalence of depression during pregnancy was found to be 9.18% based upon BDI, and it was significantly associated with several obstetric risk factors like gravidity (P = 0.0092), unplanned pregnancy (P = 0.001), history of abortions (P = 0.0001), and a history of obstetric complications, both present (P = 0.0001) and past (P = 0.0001).

Conclusions:

Depression during pregnancy is prevalent among pregnant women in Navi-Mumbai, and several obstetric risk factors were associated to depression during pregnancy. Future research in this area is needed, which will clearly elucidate the potential long-term impact of depression during pregnancy and associated obstetric risk factors so as to help health professionals identify vulnerable groups for early detection, diagnosis, and providing effective interventions for depression during pregnancy.

Keywords: Antenatal depression, beck depression inventory, depression during pregnancy, obstetric factors, prevalence

Pregnancy and its associated complications have been an issue of public health concern throughout the world. Pregnancy and the transition to parenthood involves major psychological and social changes in the mother, which have been linked to symptoms of anxiety and depression.[1]

Depression affects about 20% of women during their lifetime, with pregnancy being a period of high vulnerability.[2] Depression during pregnancy is a matter of public health importance due to 3 prime reasons: Firstly, rate of depression during pregnancy is high during antenatal period.[1,3] Secondly, it is the strongest risk factor for post-natal depression.[4,5,6] Thirdly, it leads to adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.[7] Thus, makes depression during pregnancy a matter of great importance.

Depression is also the most prevalent psychiatric disorder during pregnancy, and several studies have documented prevalence range from 4% to 25%.[2,3,4,5,8,9,10,11,12,13] with point prevalence of 15.5% in early and mid pregnancy, 11.1% in 3rd trimester, and 8.7% in post-partum period.[1] Other studies using a variety of depression assessment tools have reported antenatal depression prevalence of 9% to 28% for predominantly middle class samples[14,15] and 25% to 50%[14,15,16] for low income populations.

Several risk factors predispose to depression during pregnancy. Some of them are poor antenatal care, poor nutrition, stressful life events like economic deprivation, gender-based violence and polygamy, previous history of psychiatric disorders, previous puerperal complications, events during pregnancy like previous abortions, and modes of previous delivery like past instrumental or operative delivery. Other factors include age, marital status, gravidity, whether pregnancy was planned or not, previous history of stillbirth, previous history of prolonged labor, and level of social support.[2,3,4,8,17,18,19,20] Thus, assessment of depression during pregnancy is essential for detecting pregnant women in need of intervention in order to safeguard the well-being of mother and baby.

Despite being an important public health issue, most Indian studies of maternal depression have focused on post-natal depression, and there is paucity of data on depression during pregnancy.[21,22] Hence, this study was conducted with an aim to find the prevalence of depression during pregnancy and its association with certain obstetric risk factors in pregnant women attending tertiary care hospital in Navi Mumbai.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was an open-label, cross-sectional, observational type of study done in the outpatient department (OPD) of the department of obstetrics of a tertiary care hospital in Navi-Mumbai and conducted for the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Short Term Research Studentship (STS-2011) Program. Permission from ethics committee was obtained. The sample size was 185 (based upon prevalence of 14%, 95% confidence interval with 5% marginal error). The study duration was 2 months (June-August 2011), in which pregnant women of 18 years and above attending routine antenatal checkup was randomly selected for participation in this study. After obtaining informed consent, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was administered to detect symptoms of depression and their socio-demographic data along with the obstetric history was recorded. We excluded women in labor or in post-natal period, women consuming any type of psychotropic medications, and repeat attendees.

The Beck Depression Inventory Scale (BDI)[23,24] is the most widely used screening instrument for detecting symptoms of depression. It is a valid scale and tested to detect symptoms and severity of depression. It is a 21-item measure designed to document a variety of depressive symptoms the individual experienced over the preceding week. Responses to the 21 items are made on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 to 3 (total scores can range from 0 to 63).[24]

BDI cut-off scores used for detecting depression in several research literatures have ranged from 8.5 to 16.5.[25] A cut score of either 17 or 18 provide the best balance between sensitivity and specificity.[24,26,27,28,29] Therefore, we used BDI cut-off score of 17 or more to detect symptoms of depression in our study.

The study data was analyzed on the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version-20 software with ‘P’ value less than 0.05 taken to be statistically significant. Pearson's Chi-Square test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical data to test for the association and probability. Data was expressed in terms of mean and percentages.

RESULTS

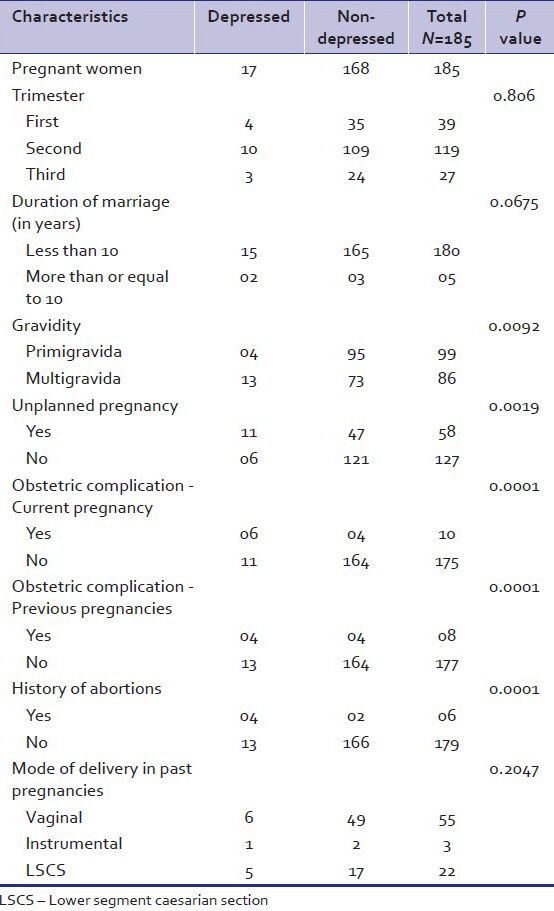

The total number of pregnant women analyzed in this study was 185. The mean age of the sample was 27.30 (±3.16) years. The prevalence of depression during pregnancy was found to be 9.18% (17) using BDI cut-off value of 17 or more in this study. The pregnant women were dichotomized into those having depression (n = 17) and those who were non-depressed (n = 168) based upon the BDI cut-off value of 17. Table 1 shows the comparisons and analysis of depressed and non-depressed pregnant women in our sample and their correlations with various obstetric risk factors. Depression during pregnancy was significantly associated with multigravidas (P = 0.0092), unplanned pregnancy (P = 0.0019), obstetric complications during current pregnancy (P < 0.0001), previous history of obstetric complications (P < 0.0001), and a previous history of abortions (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Analysis of comparison of depressed and non-depressed pregnant women and their association with various obstetric variables

DISCUSSION

In this study, an attempt has been made to examine the prevalence of depression during pregnancy (using the Beck's Depression Inventory) and its association with certain obstetric risk factors.

The prevalence of depression during pregnancy in our study was found to be 9.18% (using the BDI), which was on the lower side of the 5% to 25% prevalence of antenatal depressive symptoms reported by several other studies with different rating scales.[2,3,4,5,8,9,10,11,12,13] We were not able to compare our prevalence finding with other Indian studies since there is a paucity of Indian data and majority of the work has been focused on post-natal depression. The lower side prevalence in our population probably reflects both the specificity of the Beck Depression Inventory at a cut-off score of 17 and more and the comparatively high socio-economic position of our sample. Another reason for getting a low prevalence could be that the women in our sample population had a better support group in form of family and friends and hence may have been able to handle the stress of pregnancy better.

There are several risk factors that predispose to depression during pregnancy.[18,20,28,30] In our study, we mainly focused on obstetric risk factors and found that multigravidas, unplanned pregnancy, and pregnant women with current obstetric complications, history of previous abortions, and a past history of obstetric complications were significantly associated with depression during pregnancy. This was similar to the findings from various other studies.[2,3,8,17,19]

We found that previous history of abortions and history of obstetric complications in the past was significantly associated with depression during pregnancy. We also found that unplanned pregnancy was significantly associated with depression during pregnancy, which was similar to the studies done by Rich-Edwards et al.[2] and Patel et al.[22] who had documented that unplanned pregnancy had two-fold risk of antenatal depression. The most likely reasons could be that these are severely stressful events during pregnancy, which increase the vulnerability for depressive episodes.[1,17,20]

We also found higher prevalence of depression during pregnancy in multigravidas as compared to primigravidas. Many studies have shown that multigravidity is a risk factor for pregnancy depression.[1,31,32] There was no significant association between mode of delivery in previous pregnancies and depression during pregnancy in our study, which was similar to study done by Adewuya et al.[8]

Our study had some limitations. Since our study was conducted as a part of ICMR- Short term studentship 2011, the study had to be completed within 2 months, so the sample size was kept moderate, the time required was not feasible to conduct a full diagnostic, psychiatric clinical interview of all the patient, and also assessment for other possible co-morbid diagnoses was not done (such as anxiety disorders or dysthymia or other psychosocial factors, which could affect antenatal psychological wellbeing). Becks Depression Inventory was used to detect the presence of depression in pregnant women; therefore, we were able to examine only for the current (preceding 2 weeks) prevalence of depression and do not know whether the onset of depression was prior to the current pregnancy. The strength of our study lies in to address the issue of depression during pregnancy coming from a field of vulnerable population not yet well studied and the several obstetric variables that were significantly associated with depression during pregnancy.

In summary, our study has shown that depression during pregnancy is prevalent among pregnant women in Navi-Mumbai and detection of depression during pregnancy is an important aspect of health assessment. Several obstetric variables were found to be significantly associated with depression during pregnancy. Future research in this area is needed with a full diagnostic, psychiatric clinical interview, which will clearly elucidate the potential short-term and long-term impact of depression during pregnancy and associated obstetric risk factors. Hence, we recommend that screening for depression should be a part of the routine during antenatal checkups so that women in need of interventions can be detected and treated early, thereby preventing adverse outcomes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Teixeira C, Figueiredo B, Conde A, Pacheco A, Costa R. Anxiety and depression during pregnancy in women and men. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, Harlow BL, McLaughlin TJ, Joffe H, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:221–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira PK, Lovisi GM, Pilowsky DL, Lima LA, Legay LF. Depression during pregnancy: Prevalence and risk factors among women attending a public health clinic in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:2725–36. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wissart J, Parshad O, Kulkarni S. Prevalence of pre- and postpartum depression in Jamaican women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2005;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V ALSPAC Study Team. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004;80:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johanson R, Chapman G, Murray D, Johnson I, Cox J. The North Staffordshire maternity hospital prospective study of pregnancy-associated depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21:93–7. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Posner SF, Kourtis AP, Ellington SR, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes among women with depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:329–34. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO, Dada AO, Fasoto OO. Prevalence and correlates of depression in late pregnancy among Nigerian women. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:15–21. doi: 10.1002/da.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faisal-Cury A, Rossi Menezes P. Prevalence of anxiety and depression during pregnancy in a private setting sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan D, Milis L, Misri N. Depression during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1087–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DT, Chan SS, Sahota DS, Yip AS, Tsui M, Chung TK. A prevalence study of antenatal depression among Chinese women. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ. 2001;323:257–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseffson A, Berg G, Nordin C, Sydsjö G. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in late pregnancy and postpartum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:251–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080003251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobfoll SE, Ritter C, Lavin J, Hulsizer MR, Cameron RP. Depression prevalence and incidence among inner-city pregnant and postpartum women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:445–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Séguin L, Potvin L, St-Denis M, Loiselle J. Depressive symptoms in the late postpartum among low socioeconomic status women. Birth. 1999;26:157–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung EK, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Lee HJ, Culhane JF. Maternal depressive symptoms and infant health practices among low-income women. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e523–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hösli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:189–209. doi: 10.1080/14767050701209560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King NM, Chambers J, O’Donnell K, Jayaweera SR, Williamson C, Glover VA. Anxiety, depression and saliva cortisol in women with a medical disorder during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13:339–45. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benute GR, Nomura RM, Reis JS, Fraguas R, Junior, Lucia MC, Zugaib M. Depression during pregnancy in women with a medical disorder: Risk factors and perinatal outcomes. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65:1127–31. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yooh H, Marcus SM, Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India: Incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:499–504. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.6.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:43–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roomruangwong C, Neill Epperson C. Perinatal depression in Asian women: Prevalence, associated factors, and cultural aspects. Asian Biomedicine April Asia. 2011;5:179–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck depression inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol. 2001;20:112–9. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jesse DE, Swanson MS. Risks and resources associated with antepartum risk for depression among rural southern women. Nurs Res. 2007;56:378–86. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000299856.98170.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holcomb WL, Jr, Stone LS, Lustman PJ, Gavard JA, Mostello DJ. Screening for depression in pregnancy: Characteristics of the Beck depression inventory. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:1021–5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortner RT, Pekow P, Dole N, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. Risk factors for prenatal depressive symptoms among Hispanic women. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1287–95. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0673-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glazier RH, Elgar FJ, Goel V, Holzapfel S. Stress, social support, and emotional distress in a community sample of pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;25:247–55. doi: 10.1080/01674820400024406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiPietro JA, Costigan KA, Sipsma HL. Continuity in self-report measures of maternal anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms from pregnancy through two years postpartum. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29:115–24. doi: 10.1080/01674820701701546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]