Abstract

Background:

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating psychiatric illness consisting primarily of positive and negative symptoms. However, cognitive deficits in various domains have been consistently replicated in patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, the present study was designed to assess cognitive impairment in schizophrenia and to correlate the same with sociodemographic factors.

Materials and Methods:

Cognitive function in 100 patients with schizophrenia as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM IV-TR) criteria attending the psychiatry outpatient department (OPD) of Department of Psychiatry, SBKS MIRC was assessed using Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination Revised (ACER) rating scale and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and sociodemographic details was obtained using semistructured proforma. Data was analyzed by Chi-square and t-test.

Results:

About 70% patients of schizophrenia were found to have cognitive dysfunction for attention, concentration, memory, language, and executive function. Positive symptoms were associated with memory (P<0.001) and attention impairment (P<0.05). Patients with duration of illness >2 years and belonging to urban habitat showed more cognitive dysfunction. Male patients were associated with impairment in two domains of ACER: Language and memory.

Conclusion:

The study findings depict that persistent cognitive deficits are seen in patients with schizophrenia. Its correlation with sociodemographic factors showed that patients with >2 years of illness and belonging to urban habitat showed more cognitive dysfunction. Male patients were associated with language and memory impairment. Our study recommends that the neurocognitive impairment should be included in the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia.

Keywords: Addenbrooke's cognitive examination revised, cognitive impairment, schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating psychiatric illness consisting primarily of symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions, also termed “positive” symptoms. In addition, individuals may experience “negative” symptoms which include loss of sense of pleasure, social withdrawal, impoverishment of thoughts and speech, and flattening of affect. An eminent scientist by the name of Kraepelin (1919) coined the term dementia praecox (1896) to define the clinical manifestation of schizophrenia. Bleuler coined the term schizophrenia (Bleuler 1911) to describe the illness. Significant cognitive impairment is common in schizophrenia, affecting up to 75% of patients.

A wide range of cognitive functions are affected; particularly memory, attention, motor skills, executive function, and intelligence.

Major disturbances in episodic memory led to the suggestion that dysfunctions in hippocampal and medial temporal lobe structures were the origin of cognitive changes seen in the illness.[1] It has been known for 50 years that people with schizophrenia often perform very poorly on most cognitive tests. For instance, many neuropsychological tests require attention, concentration, working memory, and speeded processing for efficient performance even if they are really aimed at verbal learning and memory.

Recently, it has been suggested that the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia should specifically include a criterion pertaining to cognitive ability. One such possibility would require ‘’a level of cognitive functioning suggesting a consistent severe impairment and/or a significant decline from premorbid levels considering the patient's educational, familial, and socioeconomic background.[2,3,4,5,6,7]

The advantages of this approach have been thoroughly discussed in recent opinion articles by Keefe[7] and by Keefe and Fenton.[2] One of the main arguments supporting the inclusion of cognitive impairment as a diagnostic criterion is the expectation that such qualification of the clinical picture would help define a “point of rarity” between schizophrenia and closely associated affective disorders. Neurocognitive dysfunction has been postulated as a core deficit in many major mental illnesses.[8,9,10] Rather than a gene that is linked to a specific illness, it is proposed that deficits in information processing could be endophenotypes that are inherited.[11] It has been suggested that people with a lower cognitive reserve tend to have psychosis-like experiences more readily compared to those with a greater cognitive reserve.[12]

Cognitive deficits in various domains have been consistently replicated in patients with schizophrenia.[8] In patients with schizophrenia, delusions and hallucinations could arise as a result of deficits in cognitive functions involving perceptual and attribution biases.[13,14] Most studies that link cognitive deficits to functional outcome in schizophrenia support the notion that neurocognitive function predicts social and occupational function. Measures of immediate memory, delayed memory, and executive function have been found to predict functional outcome with small to medium effect size.[15] Moreover, cognitive function has been found to be a better predictor of functional outcome than symptom levels.[16]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design: Cross sectional study.

Site: Outpatient department (OPD) of Department of Psychiatry, SBKS MIRC (Dhiraj Hospital).

Study subject: Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM IV-TR) criteria.

Sample Size: 100.

Inclusion criteria

Age group 18-60 years.

Diagnosis of schizophrenia (DSM IV-TR criteria).

Previous antipsychotic therapy for 2 months.

Patients who give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

DSM IV-TR criteria Axis II disorders (mental retardation, defenses, personality traits).

A history of neurological disorders such as epilepsy, delirium, etc.

Substance dependence.

Substance-induced psychosis.

Other causes of cognitive impairment, that is, diabetes, hypertension, chronic alcoholism, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, emphysema, brain tumors, encephalitis, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), and vascular dementia.

After getting approval of Sumandeep Vidyapeeth Institutional Ethics Committee (SV IEC), the study was commenced. All patients who gave written informed consent were interviewed using:

Self-structured proforma (Appendix I).

Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination Revised (ACER) rating scale (Appendix II): The ACER is a brief cognitive test that assesses five cognitive domains; namely attention/orientation, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities. Total score is 100, higher scores indicates better cognitive functioning. Test score of 88 has 94% sensitivity and 89% specificity. Administration of the ACER takes, on average, 15 min.

Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Appendix III): MMSE is mini mental status examination to assess cognitive functions in terms of orientation, memory, language, and comprehension. It takes 5 min to administer. Total score is 30. Score of 25 is cutoff for normal cognitive function.

Analysis of data

After collecting, data was entered in database sheet and analyzed by Chi-square test. Categorical variables were described as percentage and quantitative variables were described as mean±standard deviation (SD). Univariate logistic regression was used.

Methodology

Assessments were performed in a fixed order in a quiet room. Patients were not allowed to smoke or consume stimulant drinks during the study. The last dose of medication was taken at least 12 h before the testing. The patient demographic details were taken using self-structured proforma which also includes symptoms of cognitive impairment and symptoms of schizophrenia. Following this patient was evaluated using ACER scale. Cognitive functions were assessed using ACER and MMSE.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 100 patients of schizophrenia, 54 males and 46 females were assessed for cognitive dysfunction and results are as follows.

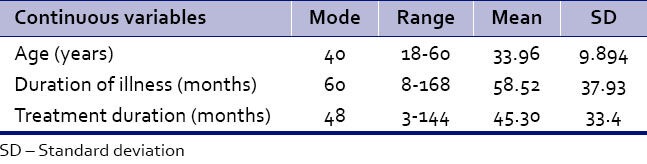

As per Table 1a, the mean age was 33.96±9.894 years. The mean duration of illness was found to be 58.52±37.93 months. The mean treatment duration was 45.30±33.4 months.

Table 1a.

Demographic characteristics of participants (mean±S.D)

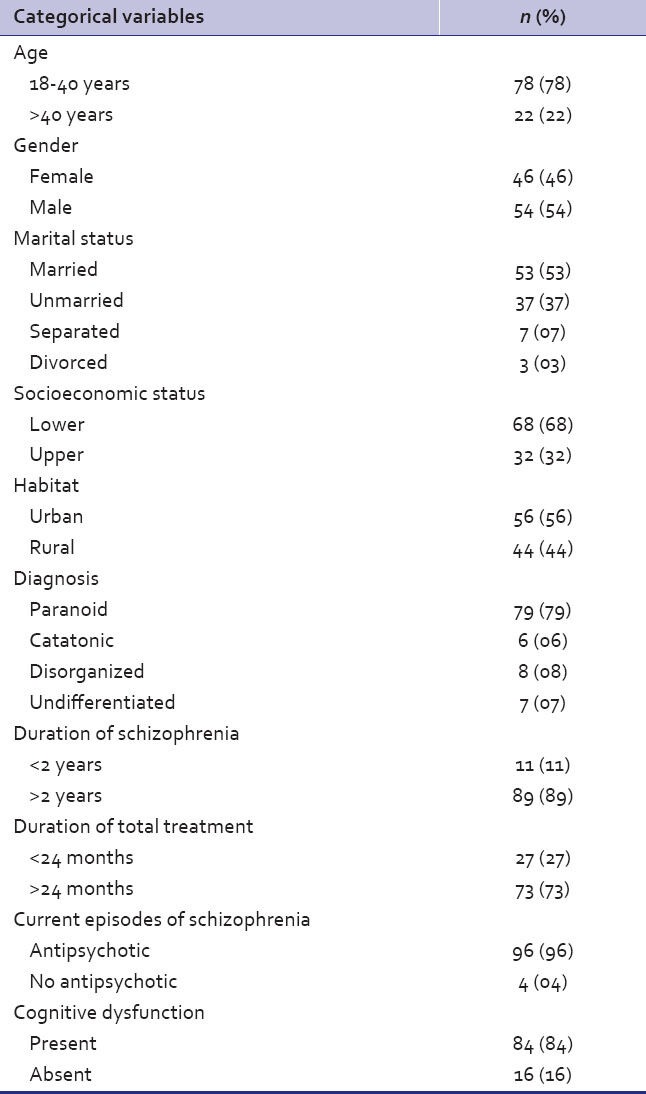

As per Table 1b, 78% belonged to age group 18-40 years; 54% of patients were males and 46% were females; 53% patients were married and 37% were unmarried; and 68% belonged to lower socioeconomic class and 56% belonged to urban habitat. As far as diagnosis is concerned, 79% were paranoid and 89% patients had schizophrenia for more than 2 years. Seventy-three percent were taking treatment for more than 24 months. Ninety-six percent patients were taking antipsychotics in their treatment for at least 2 months, while 4% had still not started with antipsychotics. On evaluating history, 84% were found to have cognitive dysfunction.

Table 1b.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n=100)

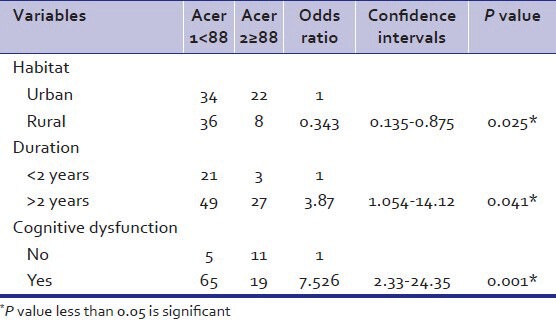

As per Table 2, cognitive dysfunction was found to be in significant number of patients (P-value<0.005). Majority were having schizophrenia for more than 2 years (P<0.05). Most of the patients belonged to urban habitat (P<0.05). No significant associations were found in age, gender, marital status, socioeconomic class, diagnosis, treatment duration, other medications taken, and ACER score.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of socio demographic factors and addenbrooke's cognitive examination revised score

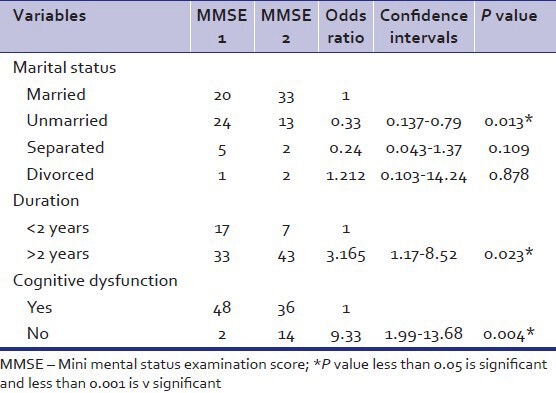

As per Table 3, unmarried had association with MMSE score (P<0.05). Duration of illness more than 2 years was found to be associated with MMSE score (P<0.023). Presence of cognitive dysfunction was also found to be statistically significant (P<0.005). No associations were found between age, sex, socioeconomic class, diagnosis, treatment duration, and other medications and MMSE score.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of sociodemographic factors and mini mental status examination score

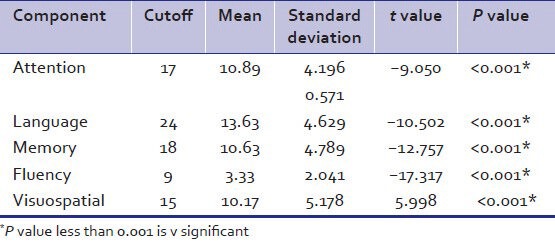

As per Table 4, the association between components of ACER namely attention, language, memory, fluency, and visuospatial abilities and cognitive dysfunction on basis of ACER score was found to be statistically significant.

Table 4.

Relation of impairment in components with addenbrooke's cognitive examination revised cutoffs

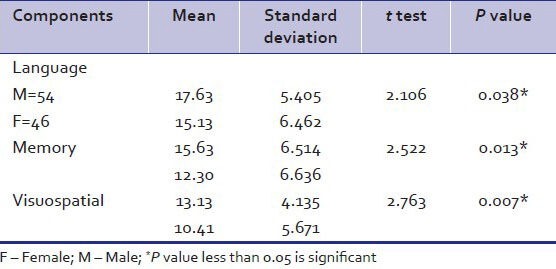

As per Table 5, male patients were associated with two components of ACER namely language and memory. The association between visuospatial abilities and and male patients was statistically significant.

Table 5.

Relation of gender with addenbrooke's cognitive examination revised components

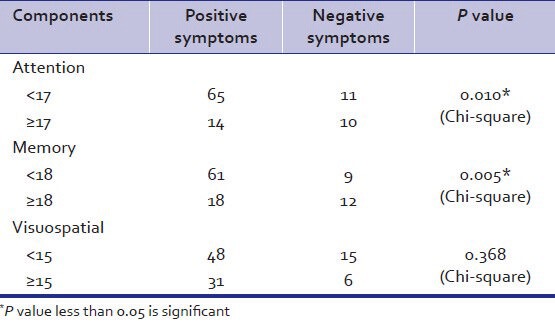

As per Table 6 association between positive symptoms and memory impairment was found to be statistically significant. Attention impairment was also associated with positive symptoms. No association between positive symptoms and other components were found.

Table 6.

Relation of components with positive and negative symptoms

Our study replicates the findings of many studies that demonstrate the presence of neurocognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia on most domains tested, including attention, concentration, immediate memory, working memory, delayed memory, and executive function.[8] A recent study from India compared the cognitive functioning of 100 symptomatic subjects with chronic schizophrenia to equal number of normal controls. It found that people with schizophrenia performed worse on all cognitive tests involving memory, attention, and executive function.[17] The present study focuses on assessing cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and to correlate it with sociodemographic factors.

Studies of neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia have revealed that cognitive impairments are present during the first-episode psychosis (FEP) (Bilder et al. and Mohamed et al.)[15,16] and remain stable throughout the course of the disorder (Heaton et al.)[17] supporting the model of cognitive deficits as primary and pathophysiologically related to schizophrenia (Bilder et al.).[18] Though there was no relation found between treatment duration and cognitive impairment. Cognitive function was found to be impaired in significant number of those patients to whom questions were asked to capture cognitive impairment in history. Meta-analyses of cognitive impairments have generally shown that patients are severely impaired and perform one to two SDs below healthy controls (Heinrichs and Zakzanis and Mesholam-Gately et al.).[19,20] Furthermore, the cognitive profile is characterized by substantial heterogeneity within a broad range of impairments including verbal memory, executive functions, attention, and processing speed (Bilder et al., Hutton et al., Mohamed et al., Riley et al., Saykin and Gur).[15,16,21,22,23]

The cognitive literature in schizophrenia has reported disproportionate impairments in almost all the cognitive processes with varying consistency and include verbal learning and memory (Albus et al., Censits et al., Saykin et al., Saykin and Gur),[25,26,27,28] speeded visual-motor processing, attention/vigilance (Weickert et al.),[29] working memory (Gold and Carpenter)[30] as well as executive functioning (Chan et al., Goldberg and Weinberger, Hutton et al., Riley et al.).[21,22,31,32] The literature to date seems to point towards verbal learning/verbal memory (Cirillo and Seidman, and Heinrichs and Zakzanis)[19,33] and processing speed (Dickinson et al., and Dickinson et al.)[24,34] as potentially the largest impairments.

The present study found no relationship of age, gender, marital status, socioeconomic status, treatment duration, and diagnosis/type of schizophrenia with ACER score except for urban habitat which was positively associated with cognitive dysfunction. Unlike ACER score, MMSE scoring had some different findings in our study. Unmarried patients showed protective results against cognitive dysfunction. This was not consistent with previous studies that show marital status to be protective factor. In contrast to previous research that found that marriage in individuals with schizophrenia affects males and females differently, this study found no such gender association between marital status and outcome. Results from several previous studies have suggested that the gender of patients with schizophrenia has a direct effect on quality of life and an interactive effect with marital status; singles, and especially males, report more cognitive dysfunction.[34]

Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest a relationship between marital status and differing symptomatology in schizophrenia based on gender. In a study of 882 psychiatric patients with schizophrenia (521 male and 361 female), Walker found that formerly married men were the most symptomatic, and currently married men the least symptomatic. In contrast, married women had a higher rate of symptoms than the never married or formerly married women.[35] Of the many reasons that no association between gender and marriage was found in this study, the most likely has to do with sample size limitations; few female participants have been enrolled, resulting in a decrease in the statistical power needed to identify gender differences. More research is needed to answer this important question.

Although research has shown that cognitive impairments are not simply the result of symptomatology (Green et al.)[36] negative symptoms have been consistently associated with severity of cognitive deficits (Harvey et al.),[37] while positive symptoms have not (Brazo et al., Heydebrand et al., Malla et al., Mass et al.).[38,39,40,41] More research investigating this relationship has shown associations between negative symptoms and specific neuropsychological deficits such as memory, attention, verbal fluency, psychomotor speed, and executive function (Bilder et al., Heydebrand et al., Zakzanis).[18,39,42]

A meta-analysis examining verbal memory in schizophrenia found that negative symptoms were the only significant variable affecting performance (Aleman et al.).[4] In our study however, positive symptoms were associated with cognitive deficits mainly memory and attention. There was no association between negative symptoms and cognitive deficits, reason for which may be that majority of patients in our study belonged to paranoid subtype presented with more positive symptoms.

Another line of research with approach to find relation between gender and components of ACER showed that males perform worse on memory and language components, which is consistent with previous studies. In the comparison of male patients with female patients, the relatively worse performance across all language domains among male patients was consistent with previous research demonstrating more impaired verbal learning and verbal fluency among male patients, compared to female patients.[43,44]

Same result goes for memory impairment which was found more in males is consistent with previous studies.[45] Several studies have shown that cognitive performances predicts work outcome such as earned income, employment status, and work duration.[46,47] However, no correlation was found between socioeconomic status and cognitive impairment in our study. Although cognitive impairment is not a sine qua non of schizophrenia, as there may be a subgroup that does not show clinically relevant cognitive deficits[48,49] the structure of DSM could easily accommodate this, since most of the disorders in the manual are defined polyethically.[50]

Several limitations of this study warrant consideration. First, the use of summary scores for each cognitive measure may prevent a thorough understanding of the various processes involved in each general cognitive domain. However, the goal of the current study was to examine the general cognitive deficits present in patients of schizophrenia. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that neuroleptic medications had a deleterious effect on neuropsychological functions even though analyses did not reveal significant correlations. Further, the small sample size may have reduced statistical power, thus potentially increasing the occurrence of type II errors.

Despite these methodological limitations, the current study has provided several improvements on previous research such as effort to find out positive and negative symptoms and cognitive dysfunction if present by asking relevant questions while taking history; the inclusion of several neuropsychological tasks assessing various cognitive domains as well as symptom assessments during the acute and stabilized phases of the illness.

CONCLUSION

The study findings depict that persistent cognitive deficits are seen in patients with schizophrenia and its correlation with sociodemographic factors was studied. Hence, the study recommends that the presence of neurocognitive impairment should be included in the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. The essence of the suggested criterion is a consistent and severe impairment in cognitive functioning as well as a significant decline from premorbid levels.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Mozley LH, Resnick SM. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: Selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:620–4. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keefe RS, Fenton WS. How should DSM-V criteria for Schizophrenia include cognitive impairment? Schizophrenia Bull. 2007;33:912–20. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficits in Schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–45. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aleman A, Hijman R, de Haan EHF. Memory impairment in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1358–66. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickinson D, Ramsey ME, Gold JM. Overlooking the obvious: A meta-analytical comparison of digit symbol coding tasks and other cognitive measures in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:532–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokat CE, Goldberg TE. Letter and category fluency in schizophrenic patients: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2003;64:73–8. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keefe RS. Should cognitive impairment be included in the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia? World Psychiatry. 2008;7:22–8. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma T, Antonova L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia. Deficits, functional consequences, and future treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson LJ, Ferrier IN. Evolution of cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: A systematic review of cross-sectional evidence. Bipolar Disorder. 2006;8:103–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braff DL, Freedman R. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Endophenotypes in studies of the genetics of schizophrenia; pp. 703–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I, Hanssen M, van Os J. Familial covariation of the subclinical psychosis phenotype and verbal fluency in the general population. Schizophr Res. 2005;74:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker CA, Morrison AP. Cognitive processes in auditory hallucinations. Attribution biases and meta-cognition. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1199–208. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans JD, Bond GR, Meyer PS, Lysaker PH, Gibson PJ, Tunis S. Cognitive and clinical predictors of success in vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan L, Thara R, Tirupati SN. Cognitive dysfunction and associated factors in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:139–43. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.55936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, et al. Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: Initial characterization and clinical correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:549–59. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohamed S, Paulsen JS, O’Leary d, Arndt S, Andreasen N. Generalized cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a study of first-episode patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:749–54. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.8.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:24–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilder RM, Lipschutz-Broch L, Reiter G, Geisler SH, Mayerhoff DI, Lieberman JA. Intellectual deficits in first-episode schizophrenia: Evidence for progressive deterioration. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:437–48. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–45. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP. Neuropsychology in first-episode schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;84:315–36. doi: 10.1037/a0014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutton SB, Purl BK, Duncan LJ, Robbins TW, Barnes TR, Joyce EM. Executive function in first-episode schizophrenia. Psycho Med. 1998;28:463–73. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley EM, McGovern D, Mockler D, Doku VC, OCeallaigh S, Fannon DG, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in first-episode psychosis: Evidence of specific deficits. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:124–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Wilk CM, Gold JM. General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:826–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albus M, Hubmann W, Mohr F, Scherer J, Sobizack N, Franz U, et al. Are there gender differences in neuropsychological performance in patients with first-episode schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 1997;28:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Censits DM, Ragland JD, Gur RC, Gur RE. Neuropsychological evidence supporting a neurodevelopment model of schizophrenia: A longitudinal study. Schizophr Res. 1997;24:289–98. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Mozley LH, Resnick SM, et al. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:618–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Mozley LH, Resnick SM, et al. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:634–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weickert TW, Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Bigelow LB, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia displaying preserved and compromised intellect. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:907–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold JM, Carpenter C, Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Auditory working memory and wisconsin card sorting test performance in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:159–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140071013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan RC, Chen EY, Law CW. Specific executive dysfunction in patients with first-episode medication-naive schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;82:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Probing prefrontal function in schizophrenia with neuropsychological paradigms. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:179–83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cirillo MA, Seidman LJ. Verbal declarative memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: From clinical assessment to genetics and brain mechanisms. Neuropsychology Rev. 2003;13:43–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1023870821631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Wilk CM, Gold JM. General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;72:826–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.010. Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:532.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker E, Bettes BA, Kain EL, Harvey P. Relationship of gender and marital status with symptomatology in psychotic patients. J Abnorm Psychol. 1985;94:42–50. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, Strakowski SM, Lieberman JA, Glick I, et al. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: Acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvey PD, Koren D, Reichenberg A, Bowie CR. Negative symptoms and cognitive deficits: What is the nature of their relationship? Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:250–8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brazo P, Marie RM, Halbecq I, Benali K, Segard L, Delamillieure P, et al. Cognitive patterns in subtypes of schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17:155–62. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heydebrand G, Weiser M, Rabinowitz J, Hoff AL, DeLisi LE, Csernansky JG. Correlates of cognitive deficits in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, Townsend L. Symptoms, cognition, treatment adherence and functional outcome in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:1109–19. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mass R, Schoemig T, Hitschfeld K, Wall E, Haasen C. Psychopathological syndromes of schizophrenia: Evaluation of the dimensional structure of the positive and negative syndrome scale. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:167–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zakzanis KK. Neuropsychological correlates of positive vs. negative schizophrenic symptomatology. Schizophr Res. 1998;29:227–33. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Hien DA, Goldman D, Deck M. Gender differences in schizophrenia (abstract) Schizophr Res. 1991;4:277. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albus M, Hubmann W, Mohr F, Scherer J, Sobizack N, Franz U, et al. Are there gender differences in neuropsychological performance in patients with first-episode schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 1997;28:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fiszdon JM, Silverstein SM, Buchwald J, Hull JW, Smith TE. Verbal memory in schizophrenia: Sex differences over repeated assessments. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:235–43. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans JD, Bond GR, Meyer PS, Kim HW, Lysaker PH, Gibson PJ, et al. Cognitive and clinical predictors of success in vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGurk SR, Moriarty PJ, Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Friedman J, et al. Relationship of Cognitive functioning, adoptive life skills, and negative symptom severity in poor outcome geriatric schizophrenia patients. J Neuropyschiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:257–64. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holthausen EA, Wiersma D, Sitskoorn MM, Hijman R, Dingemans PM, Schene AH, et al. Schizophrenic patients without neuropsychological deficits: Subgroup, disease severity or cognitive compensation? Psychiatry Res. 2002;112:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerman SW, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Toomey R, Tsuang MT. The paradox of normal neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:743–52. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.First MB, Zimmerman M. Including laboratory tests in DSM-V diagnostic criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2041–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]