Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study is to translate and validate the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Brief Version (DBAS-16)) in Hindi language.

Materials and Methods:

The scale was obtained online, and the permission for translation was obtained from the author. The translation of the scale was carried out following back translation method. The scale was applied on 63 participants attending the adult psychiatry OPD who were included in the study.

Results:

Thirty-two patients were having insomnia, and 31 patients were controls without insomnia. The results show that the translated version had good reliability with internal consistency (Chronbach alpha = 0.901).

Conclusion:

The Hindi translation of DBAS-16 is a reliable tool for assessing the dysfunctional beliefs and attitude about sleep.

Keywords: Attitudes, dysfunctional beliefs, sleep, translation

Good sleep is essential for maintaining physical and mental health. A decrease in duration of sleep is associated with obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and increased mortality from these causes.[1,2,3,4] Sleep is a complex phenomenon and is affected by a number of physiological and psychological factors.

The unrealistic expectations about sleep may cause an individual to believe that the amount of sleep that he or she is getting is not adequate. The individual may become more observant about his daytime deficit and attribute it to the perceived insomnia.[5,6] This may result in unhealthy sleep practices like spending increasing amount of time in bed, which may perpetuate insomnia. There is also evidence that specific sleep-related beliefs may influence the presenting insomnia symptoms.[7] Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), which targets these maladaptive beliefs, when used alone or along with medication, is beneficial in treatment of insomnia.[8]

Sleep practices vary in different cultures and a difference in sleep architecture between different racial groups.[9] Most of the data about the sleep studies comes from the west, and this cannot be extrapolated upon Indian patients.

To begin with, we require valid and sensitive instruments for measuring the sleep-related beliefs that may be employed in a population. To the best of our knowledge, there is no such instrument available in Hindi that may be useful in recording the sleep-related beliefs. This study was carried out to translate The Dysfunctional Belief and Attitudes about Sleep Scale (DBAS-16) in Hindi and to test its reliability.

The Dysfunctional Belief and Attitudes about Sleep Scale (DBAS-16) is a reliable and valid instrument in measuring the sleep-related cognition.[10] This scale has good internal consistency. It also measures the four correlates of (a)Consequences of insomnia, (b) worry about sleep, (c) sleep expectations, and (d) use of medication for insomnia that differentiate between “good sleepers” and “bad sleepers.”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population

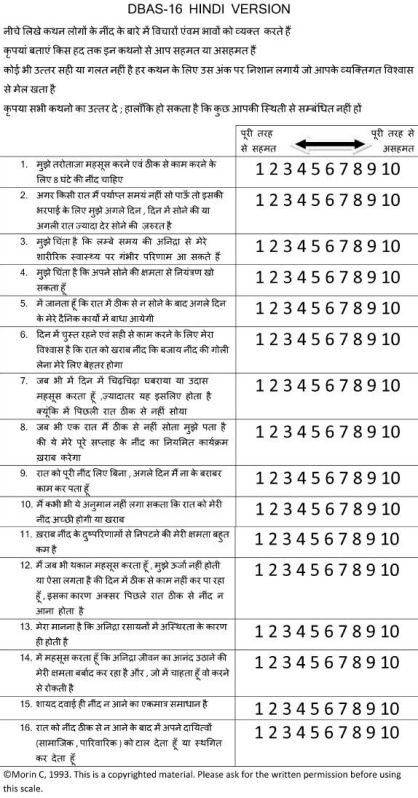

Patients attending Out Patient Department (OPD) of adult psychiatry were included in the study. After taking an informed consent, the patients were assessed on the DBAS-16 scale (Hindi Translated). Their demographic data was recorded. Diagnosis of psychiatric illness was made according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria by either of the two psychiatrists (RG, MD). Insomnia was diagnosed as per the criteria described by DSM-IV TR.[11] Subjects with long-term insomnia were given the diagnosis according to ICSD-2.[12] The patients were broadly divided into two groups of those having insomnia and other who did not report any problem with sleep; these will be considered as “insomnia” and “control” groups, respectively. Thereafter, the Hindi version of DBAS-16 was read aloud by another author (RR) to control for literacy status. Patients were explained that the replies should have reflected their beliefs regarding sleep but not the current practices that they were following. They were encouraged to provide answer on a visual analogue scale of 0 to 10, where 0 reflected complete disagreement and 10 reflected total agreement. The visual analogue scale was placed in front of them. Wherever any of the subjects experienced any difficulty in understanding the language, it was explained by one of the author (RR) and that problem was noted.

Original instrument (DBAS-16)

The DBAS-16 is a valid instrument to record the cognitions related to sleep.[10] The domains that this scale measures are expectations about sleep requirements, attributions of the causes and appraisals of the consequences of insomnia, and issues of worry and helplessness about insomnia and one factor concerned with sleep medication and biological attribution of insomnia. It has been derived from the original “Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale” scale having 30 items.

Translation procedure

The scale in English was translated into Hindi by two bilingual experts. This resulted in translated version 1 and 2. The version 1 and 2 were then matched by the two experts, and after a discussion, a common version 3 was derived. The version 3 was back translated to English and matched with the original version. There were minor discrepancies in the two versions, and the translated version was corrected accordingly to give version 4. The version 4 was agreed to be fit and was used in the present study.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was done utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v 17.0 (Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics was calculated for the groups. Independent sample t test was used to compare age and total score on DBAS-16; Chi-square was used to compare categorical variables between two groups; and Pearson's correlation was analyzed between all items of the scale. The reliability of the scale was measured by calculating the Chronbach's alpha, which depicted the internal consistency.

RESULTS

A total of 63 patients were included in the study. The average age of the population was 36.67 ± 11.06 years.

The patients were divided into two categories. There were 32 patients of insomnia group and 31 patients in control group. The average age was 38.28 ± 11.92 years and 35.00 ± 10.02 years for both the groups, respectively, (t = 0.34; P = 0.73). 56.3% of population was male in the “insomnia” group and 58.1% in the “control” group (X2 = 0.021; P = 0.88).

The sample breakup of the different type of insomnia was as follows: Insomnia co-morbid with other psychiatric disorder 59.4%, Adjustment Type 12.5%, Transient Insomnia 9.4%, Insomnia attributed to poor Sleep Hygiene 6.3%, Psycho-physiological Insomnia 6.3%, Environmental Insomnia 3.1%, and Paradoxical Insomnia 3.1%. As the individual sample size for the types of insomnias was too small for statistical analysis, all these were clubbed together to form the “insomnia” group.

The distribution of the diagnosis in the control group was as follows: Anxiety Disorder 33.3%, Depressive Disorder 25.4%, primary headache 14.3%, Restless Legs Syndrome 7.9%, Somatoform 6.3%, Conversion Disorder 3.2%, Fibromyalgia 3.2%, Recurrent Depressive Disorder 3.2%, and Substance Abuse in 3.2%.

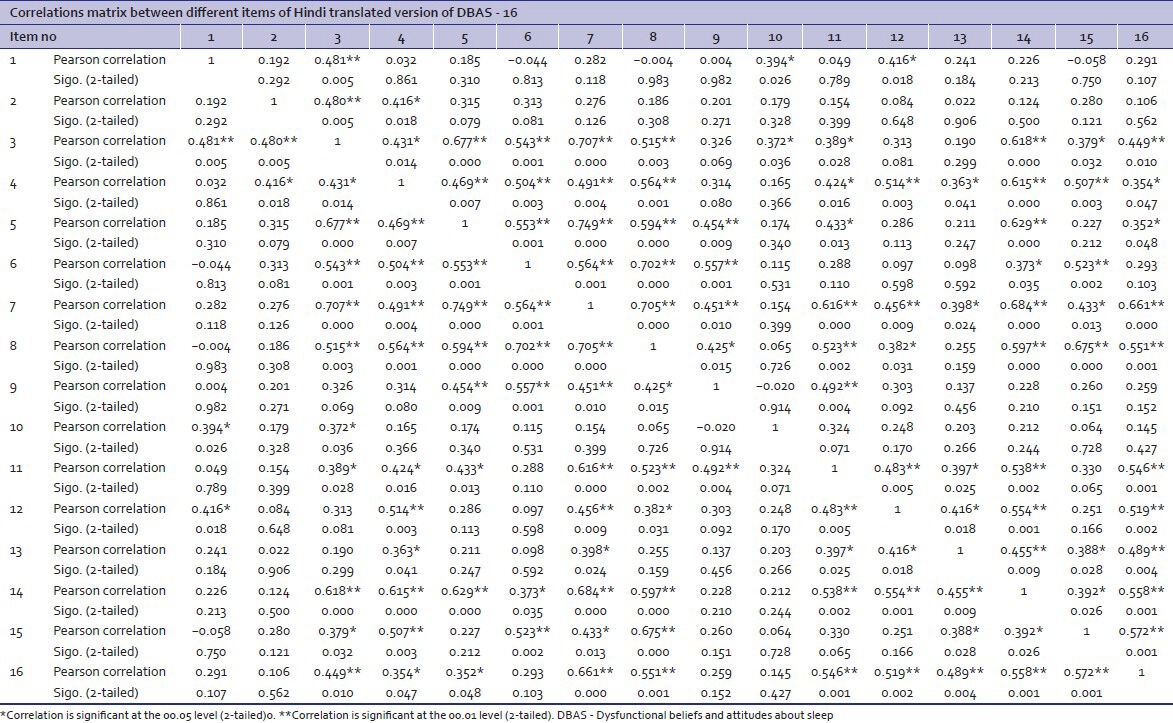

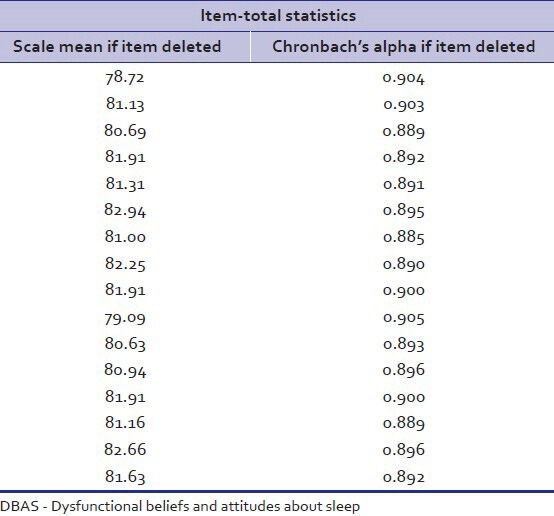

There was no significant difference in the total scores on DBAS-16 between the insomnia and the control group in this study. Table 1 showed that most of the items of the translated scale were correlated with each other. Reliability analysis depicted good internal consistency with Chronbach's alpha of 0.90. Table 2 shows the internal consistency of the scale.

Table 1.

Correlation of items in the translated version of DBAS-16

Table 2.

Reliability statistics of the translated version of DBAS-16

Translation of the scale

The scale was literally translated into Hindi by the translators at the first attempt. After the back translation, there was a need to make a few changes to retain the validity.

The word “serious” in the item 3 was translated into “vipareet” initially. In back translation, this was translated as “adverse effect.” After consultation, the word “gambheer” was used instead as it could only be back translated into “serious.” The word “alert” in item no 6 was translated to “chust” in Hindi, which was back translated into energetic. The word “chust” denotes both mental and physical alertness. After much deliberation, it was decided to keep the word “chust” only as there was no matching Hindi word in common parlance that could be substituted.

In item no 13, “I believe insomnia is essentially the result of a chemical imbalance” was back translated into “It is my belief that insomnia is basically due to imbalance of chemicals.” After discussion, the item in Hindi was reframed from “Mera manana hai kee anidra mooltaha rasayano main asithrta ke karan hoti hai” to “Mera manana hai kee anidra rasayano main asithrta ke karan hee hoti hai.”

DISCUSSION

This study found that Hindi translation of DBAS-16 is a valid tool for use in Hindi-speaking population. On searching for the term “DBAS -16” in the Cochrane library yielded 3 results, whereas search for the same term in PUBMED yielded 6 results. None of these studies was about translation of the instrument. While the 30-item original DBAS has been translated into many languages[10] such as e.g. French, Italian, German, Japanese, Swedish etc., to best of our knowledge, “DBAS-16” has not been translated into any other language. The discussion is, therefore, limited to the findings of our study.

Back translation is a popular method employed by cross-cultural researchers.[13] It has been utilized in many recent studies for translation.[14,15,16] For translation, the routine back translation method was utilized in the present study. The study was carried out as a pilot project (pre-test) to test the ease of use of the translated version and to identify problems in administration in any item. However, there were no problems faced using the scale as a routine procedure in the OPD, and patients suffering from various disorder completed the scale with ease. The patients did not report any difficulty in understanding and scoring any of the items. Therefore, it was decided that the translated version does not require further modification, and the scale can be routinely used in the routine clinical settings. The attitudes towards sleep maybe same across cultures, and this may explain the relative ease with which the scale could be translated into Hindi.

The Chronbach's alpha came out to be 0.901. When the total population of the cases and controls were taken together, the Chronbach's alpha came out to be 0.880. The internal consistency of the scale was good. The scale is, therefore, valid for measuring the beliefs related to insomnia in the population.

On comparison, the scores on DBAS of the “insomnia” group and “control” groups were comparable. A number of factors might account for this unexpected result. Firstly, the patients in the control group were also suffering from a variety of psychiatric disorder although they did not report any sleep problems in the past few days. This could have altered their response. Secondly, the insomnia group was also heterogeneous and comprised of patients with different duration of illness, ranging from transient insomnia to chronic insomnia. In future, it would be useful to compare these beliefs between persons with transient and chronic insomnia. Furthermore, the beliefs could be different between various forms of chronic insomnia - adjustment insomnia, psycho-physiological insomnia, those with poor sleep hygiene etc.[7] Hence, a comparison of these groups can shed more light on this issue. Lastly, the questionnaire records the attitudes and belief of the patients only, and the actual practice may be different, and this could explain the inability of scale to differentiate the two groups.

In summary, present study shows that this Hindi version of DBAS-16 is a valid instrument and easy to be used in routine clinical practice. Further studies to examine the test re-test reliability and to test the ability to discriminate between the “good sleepers” and “bad sleepers” are warranted in Indian population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are thankful to Dr. Charles Morin for allowing us to translate this scale in Hindi.

Appendix - A

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dimsdale JE, Ziegler M, Mills P, Delehanty SG, Berry C. Effects of salt, race, and hypertension on reactivity to stressors. Hypertension. 1990;16:573–80. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills P, Dimsdale J, Ziegler M. Lymphocyte basal cyclic AMP production predicts blood pressure. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1989;11:521–30. doi: 10.3109/10641968909035358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills PJ, Berry CC, Dimsdale JE, Ziegler MG, Nelesen RA, Kennedy BP. Lymphocyte subset redistribution in response to acute experimental stress: Effects of gender, ethnicity, hypertension, and the sympathetic nervous system. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9:61–9. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loredo JS, Soler X, Bardwell W, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE, Palinkas LA. Sleep health in U.S. Hispanic population. Sleep. 2010;33:962–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.7.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espie CA. Insomnia: Conceptual issues in the development, persistence, and treatment of sleep disorder in adults. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:215–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:869–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montserrat Sánchez-Ortuńo M, Edinger JD. A penny for your thoughts: Patterns of sleep-related beliefs, insomnia symptoms and treatment outcome. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin CM, Vallières A, Guay B, Ivers H, Savard J, Mérette C, et al. Cognitive-behavior therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:2005–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2003 National sleep disorders research plan. Sleep. 2003;26:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morinw CM, Vallières A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): Validation of a brief version (DBAS-16) Sleep. 2007;30:1547–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd ed. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2000. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cha ES, Kim KH, Erlen JA. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:386–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon CH, Kim YH, Park JH, Oh BM, Han TR. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory for head and neck cancer patients. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37:479–87. doi: 10.5535/arm.2013.37.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aulisa AG, Guzzanti V, Galli M, Erra C, Scudieri G, Padua L. Validation of Italian version of brace questionnaire (BrQ) Scoliosis. 2013;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubert F do A, Vieira NF, Pinheiro PN, Oriá MO, de Almeida PC, de Araújo TS. Translation and validation of the parent-adolescent communication scale: Technology for DST/HIV prevention. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21:851–9. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692013000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]