Abstract

Purpose of review

Prerenal failure is used to designate a reversible form of acute renal dysfunction. However, the terminology encompasses several different conditions that vary considerably. The lack of a widely accepted definition for prerenal failure makes it impossible to determine the epidemiology, natural history, and the association with adverse outcomes.

Recent findings

New diagnostic and staging criteria for acute kidney injury proposed by the Acute Kidney Injury Newtwork recognize that small increases in serum creatinine are associated with increased mortality. However these criteria have not determined specific diagnostic criteria to classify prerenal conditions. As a consequence of the lack of standardized definitions and the difficulty in assessing reversibility of AKI, the concept of prerenal has been recently challenged. The difference in the pathophysiology and manifestations of prerenal failure suggests that our current approach needs to be revaluated.

Summary

Prerenal state needs to be classified depending on the underlying capacity for compensation, the nature, timing of the insult and the adaptation to chronic comorbidities. Identification of high risk states and high risk processes associated with the use of new biomarkers for AKI will provide new tools to distinguish between the prerenal and established AKI. This review provides an appraisal of the current status and recommendations for future research in this field.

Keywords: prerenal, acute kidney injury, diagnosis

Introduction

Prerenal failure is widely accepted as a reversible form of renal dysfunction, caused by factors that compromise renal perfusion. The term has been used as part of a dynamic process that begins with a reversible condition, prerenal state, and can progress to an established disease, acute tubular necrosis (ATN). The terminology encompasses different conditions that vary considerably in the pathophysiology and course, including intravascular volume depletion, relative hypotension, compromised cardiac output, or hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). Diagnostic strategies have usually been based on demonstrating a fluid responsive change in renal function, however, the type, volume of fluid required and time for reversibility are not clearly designated. Recent attempts to define and stage acute kidney injury (AKI) have not specifically addressed this condition even though it is an integral part of the spectrum of AKI. In this review we discuss the pathophysiology of prerenal states and provide a framework for refining the diagnosis and management of prerenal failure.

The concept of kidney reserve – pre-prerenal state

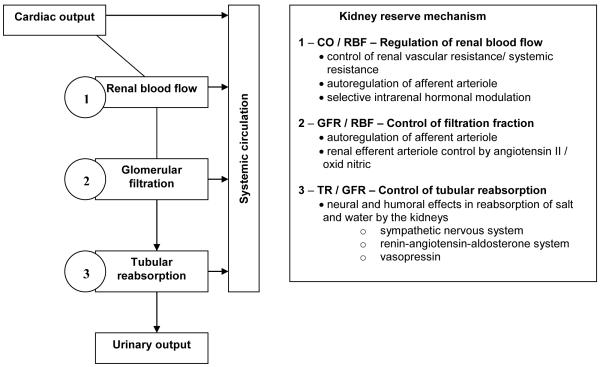

Experimental models have largely informed our current understanding of the physiology of the kidney in various settings associated with prerenal failure. Before the onset of clinically evident prerenal failure, the kidney passes through a phase of remarkable compensation called pre-prerenal failure [1]. Three main steps are involved in this compensatory mechanism; 1- the cardiac output fraction that reaches the kidney, 2- plasma flow filtration by the glomerulus (filtration fraction), and 3- proportion of the glomerular filtrate that is reabsorbed by the tubules (Figure 1). Renal blood flow (RBF) depends on the tone of renal vascular resistance (RVR) in relation to systemic vascular resistance (SVR): if the RVR increases in relation to the SVR, the RBF decreases. At reduced levels of cardiac output, intrarenal factors are triggered increasing renal arterial vascular tone and, consequently, decreasing the RBF. In order to maintain the intra-glomerular pressure, efferent arteriolar resistance increases, preserving the filtration pressure even when the pressure in the afferent arteriolar decreases to levels low enough to cease filtration. Augmented activity of the sympathetic nervous, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems and vasopressin secretion increases the amount of filtered fluid that is reabsorbed by the renal capillaries and veins.

Figure 1.

Compensatory Mechanisms in Pre-prerenal States (adapted from [1])

These three mechanisms: control of blood flow to the kidney, fraction of plasma filtered and amount of fluid reabsorbed by the kidney are the components responsible for the kidney reserve. However, the efficiency of these mechanisms has limits imposed by structural changes and the severity of the injury. The reserve is diminished by the presence of underlying arterial and intrinsic renal diseases that interfere with the control of renal blood flow, filtration fraction and the reabsorbed function, as well as by drugs that interfere with the vascular or neural humoral control of these mechanisms. When these compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed a prerenal state is discernible.

Pathophysiology of Prerenal Failure

Several mechanisms are recognized as contributory to development of a prerenal state. Maintenance of intra-glomerular filtration pressure is the key component and is influenced by the presence of underlying disease that interferes with the control of renal blood flow, filtration fraction and the reabsorbed function. The afferent arteriole can dilate and maintain adequate perfusion pressure until the systemic blood pressure falls below approximately 80 mmHg. After this point the perfusion pressure starts to decline abruptly. Structural changes in the afferent arteriole interfere with the ability to decrease the vascular tone in response to changes in their wall pressure. Old age, arteriosclerosis, diabetic vasculopathy, chronic hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are common causes impairing the appropriate vasodilatatory response. This ability is also altered by drugs that interfere with prostaglandin release or the angiotensin action in the efferent arteriole, decreasing the potential arteriolar response to a fall in the glomerular pressure and predisposing patients to prerenal failure even during minor degrees of hypotension (Table1).

Table 1.

Intrinsic Factors Decreasing the Compensatory Mechanisms and Extrinsic Factors Impairing Renal Response to Hypoperfusion

| Intrinsic Factors Decreasing Compensatory Mechanism Capacity |

Extrinsic Factors Impairing Renal Response to Hypoperfusion |

|---|---|

| Increased afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction states | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Increased afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction |

| Sepsis | Cyclosporine/Tacrolimus |

| Hypercalcemia | Radiocontrast agents |

| Congestive Heart Failure | |

|

| |

| Failure to decrease afferent arteriolar resistance | |

| Atherosclerosis | Decreased vasodilatory prostaglandins activity |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| Chronic Hypertension | Cyclooxygenase-2-inhibitors |

| Diabetes | |

|

| |

| Failure to increase efferent arteriolar resistance | |

| Failure to increase efferent arteriolar resistance | Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors |

| Renal-artery stenosis | Angiotensin-receptor-blockers |

During mild to moderate reductions in cardiac output or intravascular volume, the action of angiotensin II in the efferent arteriole is responsible for the ability to preserve the filtration fraction. If this mechanism is already in use, further increases in angiotensin II in the kidney results in a more pronounced afferent arteriolar constriction, causing a fall in the perfusion pressure and in the glomerular filtration rate.

Under normal circumstances, almost 80% of the NaCl is reabsorbed by the end of thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. If there is a failure in tubular reabsorbing mechanism, more NaCl will reach this point. The cells in the macula densa are sensitive to the increased delivery of NaCl and activate Type 2 adenosine receptors resulting in vasoconstriction of the glomerular arterioles and retraction of glomerular tuft. As a consequence urine output is decreased and urinary excretion of sodium is reduced providing a diagnostic flag of the tubular ischemic process. This tubulo-glomerular feedback mechanism is subject to perturbations particularly when loop diuretics are used. Loop diuretics reduce effective intravascular volume, and impair the autoregulatory mechanism by interfering with the reabsorption of NaCl by the macula densa cells.

Spectrum of Prerenal states

Although, prerenal failure is common in different clinical settings and generally associated with renal hypoperfusion, its pathophysiology, and consequences are quite diverse. Severe dehydration in the setting of profound diarrhea or vomiting results in hypotension and stimulates aldosterone and vasopressin through different mechanisms with the goal to retain salt and water to replenish the depleted environment. In other clinical scenarios, renal hypoperfusion can be present even in the presence of normal blood pressure [2*]. Normotensive patients are predisposed to renal hypoperfusion when intrinsic renal structural changes from premorbid conditions interfere with the reserve mechanisms, or extrinsic factors impair the compensatory mechanisms (Table 1).

In hepatorenal syndrome Type 1, considered a prerenal disease, the reduction in splanchnic and total vascular resistance occurs as a consequence of increased nitric oxide and endothelium-derived relaxing factor. With hepatic disease progression, there is a progressive rise in cardiac output and fall in SVR. The associated hypotension induces activation of the renin-angiotensin and sympathetic nervous systems causing increments in RVR, reducing GFR and sodium excretion. Any additional insult caused by gastrointestinal losses, bleeding, or therapy with a diuretic or a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug precipitates further decline in GFR.

In acute heart failure impaired cardiac output causes decreased glomerular perfusion pressure and increased venous pressure, reducing the glomerular filtration. Although extracellular fluid volume is increased, the effective (intravascular) blood volume is diminished. As a result, the renin angiotensin aldosterone system is activated, and the increased production of angiotensin II stimulates expression of endothelin 1 in the kidney, a potent pro-inflammatory vasoconstrictor. Additionally, patients with congestive heart failure frequently receive medications that further decrease the effective volume, such as diuretics, or affect the renal response to diminished perfusion, e.g. angiotensin blockers.

Considering the physiologic process, especially in sepsis, the pattern of the urinary and biochemistry values may change during the progress of the disease. In sepsis, arterial vasodilatation is followed by activation of renin-angiotensin, sympathetic nervous system, and arginine vasopressin release. The resultant renal vasoconstriction is associated with increase in tubular sodium reabsorption and decrease in urinary sodium concentration. As the disease process progresses and tubular dysfunction occurs, there is a conversion of decreased FENa to increased FENa [3]. A systematic review of septic AKI found that the urinary parameters were not useful to differentiate prerenal failure from ATN [4, 5]. Unfortunately, the time frame for the collection of these urinary and biochemical parameters and the relationship of other factors e.g. use of diuretics, and aminoglycosides to the onset of AKI need to be better determined.

In the pediatric population intravascular fluid depletion is a common cause of AKI, particularly in the pediatric ICU admission. These patients often respond solely to fluid repletion, with a return of serum creatinine to baseline values within 24 to 48 h after fluid resuscitation. A study validating the pediatric RIFLE criteria in the ICU setting compared the renal outcome and mortality of patients with an early reversal AKI, patients presenting improvement in pRIFLE within 48 h of ICU admission vs patients with persistent AKI, no improvement in pRIFLE by 48 h. Renal function improved within 48 h in 46% of patients with AKI at PICU admission. This early reversal AKI occurs more often in patients with pRIFLE R on admission than in those with pRIFLE I on admission. Fewer patients in the early reversal group received RRT than in the group with persistent AKI.

In summary, there is a wide spectrum of clinical presentations of prerenal failure that are associated with a variety of compensatory mechanisms involved in the potential reversibility of the condition. These findings suggest that the diagnosis and management of this condition likely requires consideration of several different criteria.

Diagnosis of Prerenal failure

The Acute Kidney Injury Network group has recently standardized the AKI definition and classification system, however whether AKI refers only to ATN and other parenchymal diseases or includes prerenal remains to be determined. An elevation of serum creatinine or a reduction of urine output that is easily reversible with improved hydration or improved renal perfusion pressure is the current accepted definition of prerenal failure. Unfortunately these parameters are influenced by several factors Serum creatinine levels are influenced by age, race, muscle mass, diet, volume of distribution and drugs that alter the creatinine tubular secretion. Similarly urine flow can vary according to the underlying GFR, tubular function, use of diuretics and the presence of osmotic forces. Moran et al. previously demonstrated the effect of fluid accumulation on serum creatinine concentrations and showed that increasing the total body water alters the volume of distribution of sCr resulting in underestimation of its values [6, 7]. A diagnosis of prerenal failure thus requires a consideration of these factors and other conditions such as; pre-existing disease, time frame, and response to interventions.

The most important parameter to distinguish prerenal failure secondary to volume depletion or hypotension from ATN is the response to fluid expansion. The return of renal function to the previous baseline within 24 to 72 hours is considered to represent prerenal disease, whereas persistent renal failure is called ATN. Unfortunately, there is no agreement on to the amount, nature and duration of fluid resuscitation needed to establish a prerenal state (table 1). Lab tests to distinguish prerenal failure from ATN include close examination of the urine ,plasma (P) urea/creatinine ratio, Urine (U) osmolality, U/P osmolality, U/P creatinine ratio, urinary Na level, and fractional excretion of Na (FENa) (table 2)[8, 9]. The serum U/P creatinine ratio helps to identify whether the oliguria is a result of water reabsorption (U/Pcr>20) or loss of tubular function (U/Pcr<20). The reabsorption of sodium is increased in prerenal states, not only from the increase in proximal tubular reabsorption of water, but also caused by the increase in aldosterone level secondary to hypovolemia. Common limitations for the use of FENa are associated with the frequent use of diuretic therapy in oliguric patients and in the treatment of heart and liver failure. Also, in hypovolemia associated with vomiting or enhanced loss from nasogastric tubes, the loss of acid drives a higher bicarbonaturia and maintains urinary sodium and FENa at higher than expected levels for an hypovolemic condition [18]. Besides, other causes of ATN are also associated with decreased FENa: myoglobinuria [19], contrast nephropathy [20], obstructive nephropathy [21], acute glomerulonephritis [22], among others [23].

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criterion for Prerenal Failure in Previous Studies

| Author, year |

Clinical Setting and study design |

Clinical Criteria for Prerenal | Lab criteria for prerenal | Criteria and Time Frame for Reversibility |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Liano, 1996 [10] |

prospective, multicenter, community-based study in ARF |

NA | FENa < 1% was considered as additional evidence. |

When etiologic treatment was rapidly successful in restoring renal function. |

Incidence of prerenal failure was 46 cases per million population (21% of ARF in the study) |

|

Thadhani, 1996 [11] |

review | Outpatient setting: vomiting, diarrhea, poor fluid intake, fever, use of diuretics, and heart failure. Diminished renal perfusion, Hospitalized patients: cardiac failure, liver dysfunction, septic shock. |

Dipstick test: trace or no proteinuria Sediment analysis: a few hyaline casts possible Osmolality > 500 FENa <1% |

Rapidly reversible if the underlying cause is corrected. |

No definitive time frame for diagnosis is provided |

|

Carvounis, 2002 [12]* |

Observational, single center, adults, diagnostic test for biomarker for AKI |

volume depletion, decreased cardiac output or vasodilation related to sepsis, liver failure and anaphylaxis |

Urinary sediment non-revealing in prerenal; presence of muddy brown granular casts in patients with ATN. UNa<15 mEq/L ; U/P creatinine ratio >20; FENa <1% -; FEU < 35%; UNa/K < ¼ favors prerenal failure. |

Prompt increase in urinary output and creatinine clearance after improvement of heart function, cessation of diuretic therapy or treatment of shock. |

92% of prerenal patients with no diuretic use FENa <1%, 48% with prerenal and diuretic use FENa <1% FEU < 35% in 89% of patients with prerenal and diuretic use |

|

du Cheyron, 2003 [13] |

medical ICU, observational, single center, adults, diagnostic test for biomarker for AKI |

Prerenal failure corresponded to renal impairment that rapidly improved after etiologic treatment (ie, volume repletion and/or improvement in cardiac output). |

FENa< 1% was considered additional evidence. |

None specified | Levels of urinary NHE3 normalized to urinary creatinine level were increased in patients with prerenal failure and 6 times as much in patients with ATN, without overlap |

|

Bagshaw, 2006 [4]* |

Systematic review including (27 articles-1,432 patients) describing urinary biochemistry, indices, and microscopy in patients with septic ARF. |

Heterogeneous criterion | FENa < 1%, UNa < 20 mEq/L, U/P osmolality < 1.2, or U/P creatinine ratio < 20 |

None | few data on the time dependent Evolution of urinary markers from the onset of either sepsis or ARF. The pattern and therefore value of urinary markers may be affected greatly by the timing of measurement. |

|

Salerno, 2007 [14] |

Consensus for HRS – Ascites Club |

Patients with cirrhosis with ascites. Absence of shock. No current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs. Absence of parenchymal kidney disease as indicated by proteinuria <500 mg/day, microhematuria (<50 RBC per high power field) and/or abnormal renal ultrasonography. |

Serum creatinine <1.5 mg/dl. | No improvement of serum creatinine (decrease to a level of (133 mmol/l) after at least 2 days with diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin. |

The recommended dose of albumin is 1 g/kg of body weight per day up to a maximum of 100 g/day.) |

|

Viola, 2008

[15]* |

Review HRS and ARF in cirrhosis |

Patients with cirrhosis with ascites. Absence of shock. No current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs. Absence of parenchymal kidney disease as indicated by proteinuria <500 mg/day, microhematuria (<50 RBC per high power field) and/or abnormal renal ultrasonography. |

Doubling of the initial serum creatinine concentrations to a level greater than 2.5 mg/ in less than 2 weeks |

No improvement in serum creatinine (decrease to 1.5 mg/dL or less) After at least 2 days of diuretic withdrawal and expansion of plasma volume with albumin. |

Albumin - 1 g/kg body weight/day up to a maximum of 100 g/day |

|

Nickolas, 2008 [16]** |

ER, observational, single center, adults, diagnostic test for biomarker for AKI. |

new-onset increase in serum creatinine level in the setting of historical and laboratory data suggesting decreased renal perfusion |

1.5-fold increase in serum creatinine level or a 25% decrease in estimated GFR from baseline values that satisfied minimal RIFLE criteria for serum creatinine and GFR With or not FENa < 1% at presentation. |

volume repletion or discontinuation of diuretics within 3 days |

AKI patients had markedly elevated mean urinary NGAL levels compared patients with other forms of kidney dysfunction including prerenal. |

|

Abuelo, 2008 [2]* |

Review Normotensive Ischemic AKI |

Patients with ischemic acute renal failure |

specific gravity of the urine ≥ 1.015; UNa <20 mmol per liter; FENa <1%; and FEU <35%), and the ratio of blood urea nitrogen to creatinine rises from the usual value of 10:1 to 20:1 or higher |

complete recovery may be seen 1 to 2 days after relief of the offending lesion, provided that normal perfusion or urinary outflow is reestablished before structural changes occur. |

In some cases of low systemic perfusion blood pressure may not fall dramatically but instead may remain within the normal range |

|

Akcan- Arikan, 2009 [17] |

Review, ICU pediatric patients |

AKI pediatric patients classified by the modified pRIFLE (Risk: eCCl ↓ 25% or UO<0.5 ml/kg/h for 8 h; Injury: eCCl ↓50% or UO<0.5 ml/kg/h for 16 h; Failure: eCCl ↓75% or 0.3 ml/kg/h for 24 h or anuric for 12 h) |

respond solely to fluid repletion |

with a return of SCr to baseline values within 24–48 h of fluid resuscitation (improving pRIFLE stratum within 48 h of ICU admission) |

Renal function improved (as defined by a decrease in pRIFLE stratum) within 48 h in 46% of patients with AKI at PICU admission. |

UNa: urinary sodium; (U/P) urine-plasma ; FENa fractional excretion of sodium ; FEU fractional excretion of urea; UNa/K Urinary sodium/potassium ratio; RBC red blood cells

The fractional excretion of urea (FEUN) has also been used to differentiate prerenal from ATN, especially when diuretics were used. FEUN relates inversely to the proximal reabsorption of water, and urea reabsorption leads to a decrease in FEUN and an increase in the BUN/creatinine ratio. Carvounis et al [12*], found that FEUN has a high sensitivity (85%), a high specificity (92%) and a high positive predictive value; in that study a FEUN less than 35% was associated with a 98% chance of prerenal failure. Still, there are also some limitations for the use of FEUN. In osmotic diuresis and with the use of mannitol or acetazolamide, the proximal tubular reabsorption of salt and water is impaired, so there can be a increased in FEUN even in states of hypoperfusion [24]. The same can occur when a patient is given a high protein diet or presents an excessive catabolism.

Urinary osmolality is also used to evaluate the urinary concentration ability, a function that becomes impaired in the early process of tubular dysfunction. A value greater than 500 mOsm/kg indicates that tubular function is still intact, although there are also some considerations about this index; a low protein diet can impair the concentration ability of the urine and show a low osmolality even in prerenal states.

Unfortunately, these diagnostic parameters present frequent exceptions and the distinction between prerenal and renal causes are frequently not accurate. There are some promising new biomarkers for AKI that could provide us with the tools to distinguish between prerenal and established AKI [13, 16]. During the prerenal state, the persistent vasoconstriction associated with metabolic changes and inflammation, promote the release of cell functional markers that can be detected in the blood and urine. However at the current time there are no specific markers representing prerenal conditions. Urinary NGAL levels were evaluated in emergency room patients and although the AUC for NGAL (0.948) did not significantly differ from the curve for serum creatinine (0.921). There was very little overlap in NGAL values in patient with AKI and prerenal, whereas serum creatinine values overlapped significantly [16*].

In summary, current diagnosis of prerenal conditions is relatively insensitive and would benefit from additional research to define and classify the condition. Because of the broad differences in patients reserve capacity and functional status prerenal states may be triggered at different time points. Additionally, given the variety of insults and compensatory mechanisms triggered, it is unlikely that biomarkers of renal injury would be able to distinguish all these events.

Gaps in knowledge and future directions

As a consequence of the lack of standardized definition and observational studies that could differentiate prerenal from established AKI, the prognosis of prerenal has yet to be determined. There are no studies in the incidence and consequences of prerenal failure in various clinical settings, such as perioperative, shock states including sepsis, burns, or cardiorenal syndrome. The long term consequences of episodes of prerenal failure also need to be evaluated. In patients presenting with comorbid conditions and intrinsic factors associated with decreasing compensatory mechanisms, the frequency of subclinical episodes of prerenal failure is unknown. Whether the frequency and duration of these episodes can have an impact in the progression of renal dysfunction has also to be determined. The identification of high risk states and high risk process, as well as a standardized definition could help future studies to investigate these questions.

The difference in pathophysiology and manifestation of prerenal state in these conditions suggests that our current approach to defining prerenal needs to be modified. The prerenal state could be classified depending on the underline capacity for compensation, the nature, and timing of the insult and the adaptation to chronic comorbidities. The underling reserve capacity can be normal, compromised or absent. In patients with normal renal function and absence of comorbidities, all three mechanisms of compensation can occur; control of blood flow to the kidney, fraction of plasma filtered and amount of fluid reabsorbed by the kidney. In these patients the recognition of the insult is fundamental to determine the initial therapy, as in early phases the therapy should be direct to the causative mechanism of the renal decompensation and can be rapid. For example, hypovolemic patients need fluid replacement and the reevaluation of renal function to receive the diagnostic of prerenal failure.

In the other hand, patients with already compromised kidney reserve are unable to use one or all the compensatory mechanisms. Presence of CKD (stages I to III), CHF, and other comorbidities such as myeloma, compensated cirrhosis, or the vascular alterations secondary to aging and use of ACE inhibitors, are associated with decreased ability to compensate insults. In patients presenting low cardiac output, the appropriate therapy has to be tested; volume expansion or cardiac inotropic, and depending on the cause of decompensation, enough time has to be given to reevaluate the renal function. Patients with CHF or chronic compensated liver failure, activation of neural and hormonal system leads to a permanent utilization of adaptive mechanisms by the kidney. Prerenal state frequently occurs with CHF patients when contrast agents, higher doses of diuretic therapy are used, or in patients with chronic liver failure that present TGI bleeding, paracentesis or higher dose of diuretic therapy.

In the complete absence of reserve, as in patients with CKD Stages IV/V, CHF Class IV or decompensated cirrhosis, any additional insults can determine loss of function. Progressive deterioration in renal function evidenced by progressive fibrosis of the renal parenchyma can occur in patients in whom the adaptive mechanisms are maintained for long periods of time.

Conclusion

It is evident that research in this area is urgently needed to bring further clarity to the field. We believe that the principles discussed above need to be considered in developing standardized definitions of prerenal states. Future studies would need to focus on populations at risk for prerenal failure and discover biomarkers representing the compensatory mechanisms triggered during prerenal states. It is reasonable to expect that several different markers may be used in combination to distinguish prerenal states from structural changes in the kidney. Recognizing reversible renal dysfunction early and accurately will enable timely intervention and will likely improve our ability to improve outcomes from AKI.

Acknowledgements

Etienne Macedo’s work has been made possible through her International Society of Nephrology Fellowship and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientĺfico eTecnológico) support.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Badr KF, Ichikawa I. Prerenal failure: a deleterious shift from renal compensation to decompensation. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:623–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809083191007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2] *.Abuelo JG. Normotensive ischemic acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra064398. Review of pathophysiology of ischemic AKI associated with normal blood pressure.

- [3].Schrier RW, Wang W. Acute renal failure and sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:159–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4] *.Bagshaw SM, Langenberg C, Bellomo R. Urinary biochemistry and microscopy in septic acute renal failure: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:695–705. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.017. In this systematic review the urinary biochemistry and microscopy indices in septic patients failed to present clinical evidence as a diagnostic tool to diagnoses ATN in septic AKI.

- [5].Bagshaw SM, Langenberg C, Wan L, May CN, Bellomo R. A systematic review of urinary findings in experimental septic acute renal failure. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1592–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266684.17500.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Macedo E, Bouchard J, Soroko S, Chertow G, Himmelfarb J, Paganini E, Ikizler TA, Mehta R. Delayed Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Patients. ASN Renal Week. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moran SM, Myers BD. Course of acute renal failure studied by a model of creatinine kinetics. Kidney Int. 1985;27:928–37. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Miller TR, Anderson RJ, Linas SL, et al. Urinary diagnostic indices in acute renal failure: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:47–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Espinel CH. The FENa test. Use in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Jama. 1976;236:579–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.236.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liano F, Pascual J. Epidemiology of acute renal failure: a prospective, multicenter, community-based study. Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int. 1996;50:811–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Thadhani R, Pascual M, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1448–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605303342207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12] *.Carvounis CP, Nisar S, Guro-Razuman S. Significance of the fractional excretion of urea in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62:2223–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00683.x. Fractional excretion of urea was found to be a more sensitive and specific index than FENa in differentiating between ARF due to prerenal azotemia and that due to ATN, especially in patients that received diuretics.

- [13].du Cheyron D, Daubin C, Poggioli J, et al. Urinary measurement of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) protein as new marker of tubule injury in critically ill patients with ARF. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Salerno F, Gerbes A, Gines P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56:1310–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15] *.Garcia-Tsao G, Parikh CR, Viola A. Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:2064–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.22605. This article presents a review on physiology, causes and therapy for HRS.

- [16] **.Nickolas TL, O’Rourke MJ, Yang J, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a single emergency department measurement of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for diagnosing acute kidney injury. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:810–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00003. In this single center study one measurement of urinary NGAL in the ER helped to distinguish acute injury from normal function, prerenal failure, and chronic kidney disease.

- [17].Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis LL, Washburn KK, Jefferson LS, Goldstein SL. Modified RIFLE criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1028–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nanji AJ. Increased fractional excretion of sodium in prerenal azotemia: need for careful interpretation. Clin Chem. 1981;27:1314–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Corwin HL, Schreiber MJ, Fang LS. Low fractional excretion of sodium. Occurrence with hemoglobinuric- and myoglobinuric-induced acute renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:981–2. doi: 10.1001/archinte.144.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fang LS, Sirota RA, Ebert TH, Lichtenstein NS. Low fractional excretion of sodium with contrast media-induced acute renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:531–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hoffman LM, Suki WN. Obstructive uropathy mimicking volume depletion. Jama. 1976;236:2096–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zarich S, Fang LS, Diamond JR. Fractional excretion of sodium. Exceptions to its diagnostic value. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:108–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pru C, Kjellstrand C. Urinary indices and chemistries in the differential diagnosis of prerenal failure and acute tubular necrosis. Semin Nephrol. 1985;5:224–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Goldstein MH, Lenz PR, Levitt MF. Effect of urine flow rate on urea reabsorption in man: urea as a “tubular marker”. J Appl Physiol. 1969;26:594–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.26.5.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]