Abstract

Background

von Hippel Lindau (VHL) disease is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder that results in multiple organ systems being affected. Treatment is mainly surgical, however, effective systemic therapies are needed. We developed and tested a cell-based screening tool to identify compounds that stabilize or upregulate full-length, point mutated VHL.

Methods

The 786-0 cell line was infected with full-length W117A mutated VHL linked to a C-terminal Venus fluorescent protein. This VHL-W117A-Venus line was used to screen the Prestwick drug library and was tested against the known proteasome inhibitors MG132 and bortezomib. Western blot validation and evaluation of downstream functional readouts, including HIF and GLUT1 levels, were performed.

Results

Bortezomib, MG132, and the Prestwick compounds 8-azaguanine, thiostrepton and thioguanosine were found to reliably upregulate VHL-W117A-Venus in 786-0 cells. 8-azaguanine was found to downregulate HIF2α levels, and was augmented by the presence of VHL W117A. VHL p30 band intensities varied as a function of compound used, suggesting alternate post-translational processing. In addition, nuclear-cytoplasmic localization of pVHL varied amongst the different compounds.

Conclusion

786-0 cells containing VHL-W117A-Venus can be successfully used to identify compounds that upregulate VHL levels, and that have a differential effect on pVHL intracellular localization and posttranslational processing. Further screening efforts will broaden the number of pharmacophores available to develop therapeutic agents that will upregulate and refunctionalize mutated VHL.

Keywords: VHL upregulation, proteostasis, high-throughput screen, Prestwick

INTRODUCTION

Identification of the von Hippel Lindau syndrome occurred through the observation by Eugen von Hippel, an ophthalmologist, of familial retinal hemangioblastomas in 1904 and Arvid Lindau, a neurologist, of hereditary hemangioblastomas in 1927 [1]. As more individuals with this syndrome were recognized, involvement of the kidney, with renal cysts and clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) was reported, as was involvement of the adrenal gland with pheochromocytomas and the pancreas with cysts, serous cystadenomas and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. In 1993, Latif and colleagues published the identification of the VHL gene [2], and in the intervening years a large amount of research has been performed to elucidate the function of the VHL protein (pVHL). Recognition that pVHL is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that forms a complex with elongins C and B [3] as well as Cul2 [4], enabling the mature VHL-elongin C and elongin B (VBC) complex to bind and postranslationally regulate hypoxia inducible factors 1 and 2 (HIF1 and HIF2) [5] and that this process required prolyl hydroxylation of HIF [6] provided a better understanding of the highly vascular nature of most lesions arising in the background of a VHL mutation. The discovery of VHL’s HIF regulatory capacity, and the impact of unbridled HIF expression on the expression of multiple proangiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), led to the development of multiple therapeutic agents targeting the VEGF pathway in neoplasms [7–10]. Although these agents have demonstrated biological and clinical activity in neoplastic diseases, including clear cell RCC, which in both the germline and sporadic setting demonstrate near universal inactivation of VHL, there have been few recorded examples of complete tumor regression or cure. Even more troubling has been the near complete lack of activity of these agents in hemangioblastomas, a highly vascular but noninvasive or nonmetastasizing lesion that arises in the eye, cerebellum, brainstem and spinal cord of patients with VHL syndrome.

Reasons for the lack of greater benefit from VEGF-axis blocking agents have not been fully elucidated. Possibilities include redundancy in the proangiogenic signaling network, with both innate and acquired resistance pathways likely present. The elucidation of a number of novel functions for VHL, including regulation of the primary cilium [11] and the cilia centrosome cycle, and regulation of extracellular matrix deposition via binding to collagen IV [12] and fibronectin [13], demonstrate that management of the HIF-related effects of VHL loss may not be sufficient to reverse the neoplastic phenotype in germline or sporadic cases of VHL-related diseases.

In an effort to better understand the pathogenesis of VHL mutations, genotype-phenotype correlations have been made between specific classes of VHL mutations and their clinical and biological significance. VHL is a 213 amino acid protein with three exons [14, 15]. As of now, there have been no recognized nonpathogenic polymorphisms. Approximately one third of all VHL mutations are missense, resulting in the generation of a full-length protein [15]. Data demonstrate that point-mutated pVHL is less stable than wild-type protein [16], and is rapidly cleared from the cell via heat shock protein-mediated proteasomal degradation [17, 18], despite maintaining residual functionality in some cases [16]. In addition, there is a distinct subset of VHL mutations that render nascent VHL incapable of binding to the eukaryotic type II chaperonin tail-less complex polypetptide-1 (TCP -1) ring complex (TRiC) also called CCT for chaperonin containing TCP-1 [19]. These mutations occur in amino acids (aa) 114 to 119 and 148 to 155 and constitute the two major TRiC-binding domains, named Box 1 and Box 2, respectively [17]. By failing to bind to TRiC, VHL cannot fold into its mature form, and cannot generate a mature VBC complex. Furthermore, disease-causing mutations in the region spanning aa 155–181 demonstrate decreased binding of elongin C [3]. Failure to load elongins C and B onto VHL results in the failure of VHL release from TRiC, and more rapid degradation of pVHL [20].

We hypothesized that compounds that restabilize mutant pVHL, either through decreased proteasomal degradation, or via the facilitation of refolding and proper VBC complex formation, would aid in the reacquisition of a normalized cellular phenotype. To discover compound leads that could test our hypothesis, we generated VHL deficient 786-0 cell lines that contain Venus [21] high-intensity fluorescence tagged pVHL with a highly unstable W117A mutation, evaluated VHL levels after proteasome inhibitor treatment, and screened the 1120 compound Prestwick library for other compounds that manipulate VHL levels. We discovered three compounds which were able to reliably upregulate pVHL W117A levels. Our data also provide an intriguing new mechanism of action for bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor in clinical use and which has shown some efficacy in RCC, and the ability of the VHL-W117A-Venus containing cell line to be used as an assay to successfully identify candidate molecules that consistently increase intracellular pVHL levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and plasmids

RCC 786-0 and HEK293T cell lines were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium from Invitrogen, (Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). VHL-wt-GFP plasmid was from Dr. Paul Corn (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX). Venus expressing plasmid Venus/pCS2 was from Dr. Atsushi Miyawaki (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan). VHL-wt-Venus was made by replacing GFP in VHL-wt-GFP with Venus from Venus/pCS2 as a BamHI/XbaI fragment. VHL-W117A-Venus mutation fusion was made from VHL-wt-Venus by mutagenesis with Quikchange mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) and confirmed by sequencing. (Primers for the mutagenesis: GCTACCGAGGTCACCTTGCGCTCTTCAGAGATGCAGG and CCTGCATCTCTGAAGAGCGCAAGGTGACCTCGGTAGC). Retroviral vector pLEGFP-N1 was from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). Retroviral expression plasmids VHL-wt-Venus-Retro and VHL-W117A-Venus-Retro were made by moving VHL-wt-Venus or VHL-W117A-Venus gene fragment into pLEGFP-N1 to replace GFP. VHL-W117A was made by digestion of VHL-W117A-Venus with BamHI/XbaI followed by blunting and religation to remove Venus. Cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent from Roche (Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Retrovirus preparation and infection were performed as previously described [22].

Reagents and antibodies

MG132 was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Bortezomib was from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX). Candidate drugs were from Prestwick (Prestwick Chemical, Illkirch, France). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Western blotting antibodies for VHL (#2738) and IGF1R (#3018) were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Antibody for HIF2α (#NB100–122) was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibody for Glut1 (#GT12-A) was from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX). GAPDH (#AM4300) was from Ambion (Austin, TX)

Western blotting and cell proliferation assay

To prepare cell lysates for western blotting, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM; NaCl, 150 mM; NP-40, 1%; Sodium deoxycholate, 0.5%; SDS, 0.1%) supplemented with protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Western blotting was performed as previously described [22]. Cell proliferation was determined by CellTiter Blue Cell Viability assayf rom Promega (Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

High Throughput Microscopy and Image Analysis

For the Prestwick compound screen, VHL-W117A-Venus 786-0 cells were plated at 6,000 cells in 100μl per well of complete culture media in black Corning from Corning Life Sciences (Lowell, MA) 96-well optical plastic bottom plates and incubated an additional 12–18 hours to allow for cell adhesion and spreading. Compound dilutions and final addition to multi-well plates were performed using the multichannel pod of a Beckman Biomek FX robotic platform to ensure repeatability from experiment to experiment. Compounds from the Prestwick Chemical Compound Library (Prestwick Chemical, Illkirch, France) were initially diluted 10-fold from a stock containing 2mg/ml in DMSO with cation-free phosphate buffered saline (PBS, MediaTech, Inc., Manassas, VA). The test compounds were further diluted 20-fold by addition to assay wells. Basal expression levels of VHL-W117A-Venus were determined in cells treated with PBS containing a final concentration of 0.5% DMSO. The agonist-induced phenotype was determined in control wells treated with 0.5μg/ml N-(benzyloxycarbonyl) leucinyl-leucinyl-leucinal (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al or MG132) in 0.5% DMSO. After incubation for an additional 20–23 h, plates were washed with PBS and fixed for 20 min at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (Affymetrix-USB, Santa Clara, CA). After fixation, cells were briefly permeabilized (5 min) with 0.5% Tween 20 (v/v) and prepared for imaging by washing in PBS, removing the wash solution, and adding a 1μg/ml DAPI solution, staining DNA to facilitate nuclear image segmentation. Cells were imaged in PBS.

Cells were imaged using the Beckman Cell Lab IC-100 Image Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) platform that consists of 1) Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon; Melville, NY); 2) Chroma 82000 triple band filter set (Chroma; Brattleboro, VT); 3) a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER Digital CCD imaging camera (Hamamatsu; Bridgewater, NJ); and 4) a Photonics COHU Progressive scan focusing camera (Photonics; Oxford, MA). The microscope was equipped with a Nikon S Fluor 20X/0.75NA objective and the imaging camera set to capture 8 bit images at 2×2 binning (1344 × 1024 pixels; 0.42 μm2 pixel size) with two channels captured per field: channel 0 (DAPI, Ex 350/50nm, Em 420nm/Long pass) was used to find the focus and cell nuclei and channel 1 was used to image VHL-W117A-Venus (Venus, Ex 490/20nm, Em 517/30nm). In general, 16 fields were captured per well for image analysis.

Images were analyzed using Cytoshop Version 2.1 (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis IN) as described by Szafran et. al.[23] Image processing began by applying a general automatic mean background subtraction in each of the channels and the removal of partial cells visible at the edges of each frame. Next, cells were identified by using nuclear masks generated by a combination of image filters and automatic histogram based thresholding. Total area of the cells was determined by intersection of a chosen extraction radius (approximately 25% larger than average nucleus radii) and tessellation polygons generated by the software. Agonist-induced VHL-W117A-Venus fluorescence levels were determined as the total integrated pixel intensity in the GFP channel (CORR1). All values were corrected for background VHL-W117A-Venus fluorescence measured in the DMSO-only control wells.

RESULTS

1. Identification and Characterization of Unstable VHL-W117A-Venus Mutation

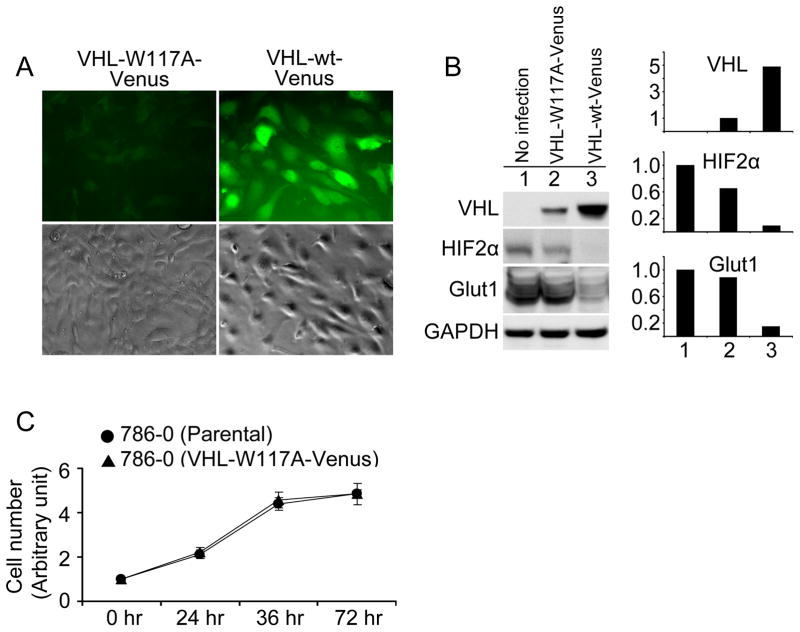

To generate a screening tool that permits identification of compounds that restabilize mutant VHL, we mutated codon TGG to GCG, which results in a tryptophan to alanine alteration at amino acid 117 within the Box 1 TRiC binding region. This sequence was placed in a pLEGFP-N1 retroviral vector, fusing VHL W117A to a C-prime Venus high-intensity fluorescent tag (VHL-W117A-Venus), and infected into the VHL−/− 786-0 cell line (VHL-W117A-Venus). A similar strategy was used to generate a 786-0 line containing Venus-tagged wild-type VHL. Comparison of fluorescence intensity levels between VHL-W117A-Venus and VHL-wt-Venus demonstrated a significant decrease in mean fluorescence intensity of the VHL-W117A-Venus cells despite similar cell confluence (Fig. 1A). Levels of HIF2α and Glut 1, a HIF-regulated gene product, were decreased in a VHL-dependent fashion (Fig. 1B). Growth rates of 786-0 parental cell lines were similar to VHL-W117A-Venus lines (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. VHL stability affected by W117A mutation.

(A) Comparison of fluorescence level between VHL-W117A-Venus and VHL-wt-Venus. VHL null 786-0 cells were infected and selected with G418 for stable cell lines expressing VHL-W117A-Venus or VHL-wt-Venus. At least 100 cells were examined by inverted fluorescence microscope from different fields for each sample. Representative fluorescent and phase contract images are shown. (B) Protein levels of VHL fusions and downstream targets. Cells were cultured in complete medium and were lysed in RIPA buffer supplied with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates (50μg/lane) were resolved in 7.5% SDS PAGE for HIF2α blots and in 10% SDS PAGE for others. Antibodies for each blot are listed to the left of the blots. GAPDH immunoblotting shows equivalent loading. Lane 1, Parental 786-0 without infection; Lane 2, 786-0 expressing VHL-W117A-Venus, and Lane 3, 786-0 expressing VHL-wt-Venus. Scanning densitometric values of Western blots were obtained with NIH IMAGE J software. All densitometric values were first normalized to GAPDH. Data of VHL fusions are presented as relative conversion to values of VHL-W117A-Venus. Data of HIF2α and Glut1 are presented as relative conversion to values of parental 786-0 cells. (C) Effect of VHL-W117A-Venus on cell proliferation. Cells of 786-0 parental and 786-0 expressing VHL-W117A-Venus were plated in 96-well plates in complete medium at 3000 cells/well. Cells were incubated overnight for cell attachment as the start point of measurement. Cell number was measured by CellTiter Blue Cell Viability assay according to manufacturer’s protocol at the indicated time points. Data are presented as relative conversion to values at 0 hr for each cell line. Standard deviation of triplicate is shown as error bars.

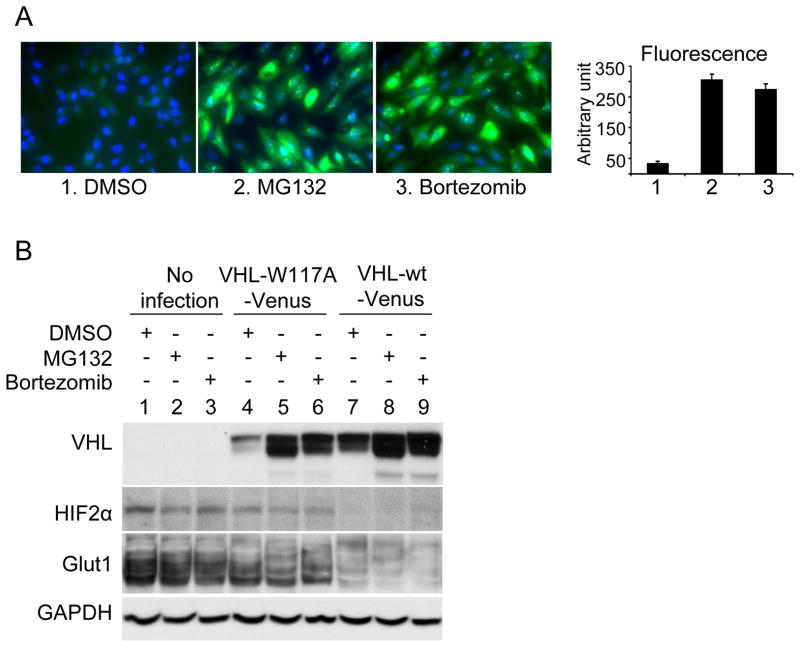

We then tested whether a proteasome inhibitor could upregulate VHL levels in VHL-W117A-Venus containing 786-0 cell lines. As seen in Figure 2A, the addition of MG132 or bortezomib resulted in significant upregulation of fluorescence levels. To confirm that VHL protein levels were increased, we performed Western blots on MG132 and bortezomib treated samples and demonstrated an increase in VHL-W117A-Venus levels (Fig. 2B). Increased WT VHL levels were also noted after proteasome inhibitor treatment, but to a lesser degree when compared to the mutant form. Hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha (HIF2α) is one of the primary downstream substrates of VHL. Nonsignificant changes in HIF2α levels were detected in MG132 and bortezomib treated VHL W117A cells (Fig. 2B), as well as in levels of Glut 1, a HIF-responsive protein, whereas wild-type VHL fully suppressed HIF2α and nearly completely suppressed Glut1.

Figure 2. Effect of proteasome inhibition on stability of VHL-W117A-Venus.

(A) Effect of proteasome inhibition on fluorescence intensity of VHL-W117A-Venus cells. VHL-W117A-Venus expressing 786-0 cells were treated with proteasome inhibitors MG132 (1μg/ml) or Bortezomib (0.05μg/ml) for 24 hours. Images were obtained and fluorescence level was measured by Beckman Coulter Cell Lab IC100 Image Cytometer and analyzed by CyteSeer software. Representative quantification of fluorescence intensity of the three treatments was shown. Data are presented as arbitrary fluorescence units. Standard deviation of triplicate of each treatment is shown as error bars. (B) Effect of proteasome inhibition on protein level of VHL-W117A-Venus. The three cell lines were treated with proteasome inhibitors MG132 (0.5μg/ml) or Bortezomib (0.02μg/ml) for 24 hours. Lane 1–3, parental 786-0 cells; Lane 4–6, VHL-W117A-Venus cells; and Lane 7–9, VHL-wt-Venus cells. Antibodies for each blot are listed to the left of the blots.

2. High Throughput Screen to Detect VHL Modulating Compounds

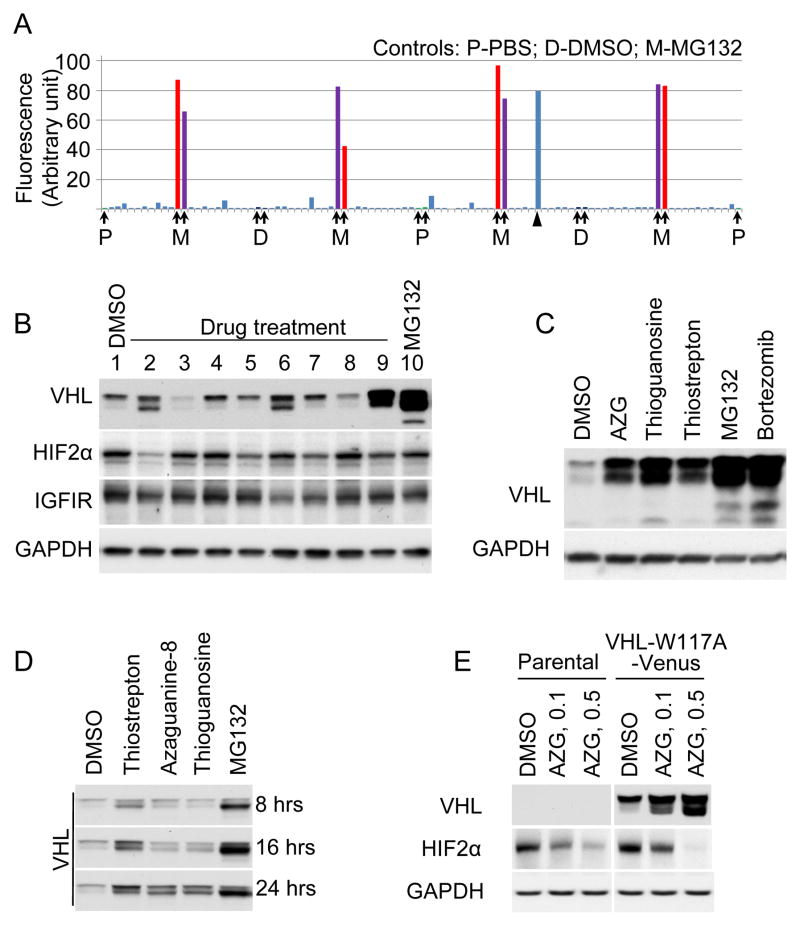

To screen for compounds that upregulate mutated VHL levels, we generated a 96-well based system using VHL-W117A- Venus infected 786-0 cells, and tested the Prestwick 1120 compound library. Figure 3A shows a representative plate result. MG 132 stimulated fluorescence levels of VHL-W117A-Venus protein were on average 61-fold greater than background levels (signal to background ratio). Overall assay quality was determined using the z′-calculation. A mean z′-factor of 0.5 (n=34) was determined from all primary screening plates. Candidates were chosen on the basis of cellular fluorescence intensity as well as on relative viability of cells after treatment with compound (data not shown) resulting in the identification of eight “hit” compounds (Table 1) that increased fluorescence. Candidate compounds were validated by evaluating levels of VHL protein after treatment. As seen in Figure 3B, compounds in lane 2, 6 and 9 demonstrated substantial upregulation of VHL levels. Compound in lane 2 is 8-azaguanine, compound in lane 6 is thioguanosine and compound in lane 9 is thiostrepton (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Proof-of-concept screen and candidate validation.

(A) Proof-of-concept screen with the Prestwick chemical library. A representative data set of a 96-well plate in the screen. Negative controls (P, PBS; D, DMSO) and positive control (M, MG132 at 0.5μg/ml) on the plate are designated by arrows. One positive hit on the plate is designated by arrow head. (B) Validation of candidate drugs on VHL-W117A-Venus protein stability. VHL-W117A-Venus cells were treated with the candidate drugs (10μg/ml) for 24 hours. Lane 1, DMSO negative control; Lane 2–9, drug treated for 24 hours at 10 μg/ml (Lane 2, Azaguanine-8; Lane 3, R(−) Apomorphine hydrochloride hemihydrate; Lane 4, Dyclonine hydrochloride; Lane 5, Ethacrynic acid; Lane 6, Thioguanosine; Lane 7, Colchicine; Lane 8, Lovastatin; Lane 9, Thiostrepton). Lane 10, MG132 positive control (1μg/ml for 24 hours). Antibodies are listed to the left of the blots. (C) Structure of the validated drugs.

TABLE 1.

Candidate compounds identified from Prestwick Chemical Library screen: Numbers correspond to lanes in Figure 3B.

| No. | Compound name | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control Lane: DMSO | ||

| 2. | Azaguanine-8 | C4H4N6O | 152.12 |

| 3. | R(-) Apomorphine hydrochloride hemihydrate | C34H38Cl2N2O5 | 625.58 |

| 4. | Dyclonine hydrochloride | C18H28ClNO2 | 325.87 |

| 5. | Ethacrynic acid | C13H12Cl2O4 | 303.14 |

| 6. | Thioguanosine | C10H13N5O4S | 299.31 |

| 7. | Colchicine | C22H25NO6 | 399.44 |

| 8. | Lovastatin | C24H36O5 | 404.54 |

| 9. | Thiostrepton | C72H85N19O18S5 | 1664.89 |

3. Functional Assessment of Candidate Compounds

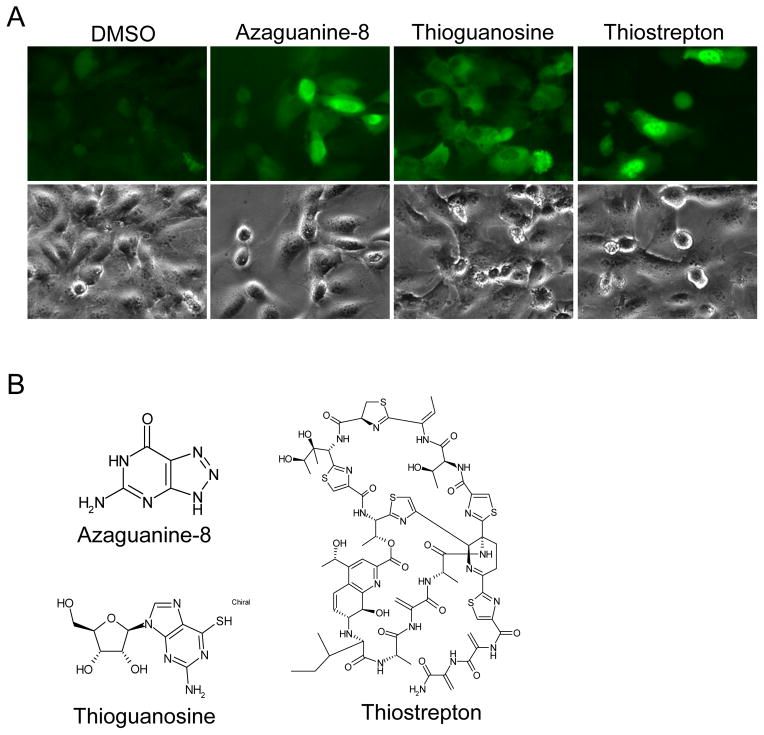

To better understand the impact of compound induced upregulation on VHL function, we assessed the impact of 8-azaguanine, thioguanosine and thiostrepton on VHL effector protein levels. As shown in Figure 3B, HIF2α was significantly downregulated by 8-azaguanine in 786-0 VHL-W117A-Venus cells. Compared to DMSO controls, thioguanosine, thiostrepton and MG132 did not impact HIF2α levels significantly. To assess effect of candidate compounds on untagged VHL W117A, HEK293T cells were transiently transfected to express VHL-W117A without tag. The same proportional drug effect was seen (Fig. 4A). To better understand the kinetics of VHL increase as a function of treatment time, the timecourse of VHL increase was assessed in 786-0 VHL-W117A-Venus cells (Fig. 4B). Total levels increased in a fairly linear fashion over the 24 hour period, with differential upregulation of the upper vs. lower pVHL band. Further evaluation of the significance of the two bands revealed that phosphatase treatment (Data not shown) did not affect either band, suggesting that other post-translational modifications are responsible for the different bands. In addition, transfection of 786-0 cells with p19 form of VHL lacking the 53 N-terminal amino acids confirms a 19 kilodalton size, and rules out the possibility this additional band is due to known internal start site-dependent regulation (Data not shown). Further evaluation of HIF2α levels in the parental 786-0 line revealed that HIF2α levels also decreased in a VHL independent fashion (Fig. 4C), suggesting a VHL independent mechanism of action for the effect of 8-azaguanine on HIF2α level is also operative. To better understand the impact of the compounds on VHL intracellular localization, we evaluated fluorescent images of VHL-W117A-Venus 786-0 cell lines (Fig. 4D). These reveal different VHL distribution patterns: 8-azaguanine results in a fairly homogeneous cytoplasmic- and nuclear distribution. Thioguanosine treatment results in an intriguing nuclear exclusion of VHL, and thiostrepton induces a predominant nuclear distribution.

Figure 4. Functional Assessment of Candidate Compounds.

(A) Validation of candidate drugs on VHL-W117A protein stability. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected to express VHL-W117A without tag. Transfected cells were evenly subcultured into 6 plates to ensure equal expression of VHL-W117A. Cells were treated with candidate drugs (Azaguanine-8 at 5μg/ml, Thioguanosine at 10μg/ml, Thiostrepton at 10μg/ml) and controls (MG132 at 0.5μg/ml, Bortezomib at 0.01μg/ml) for 24 hours, indicated above the blots. Antibodies are listed to the left of the blots. (B) Effect of candidate drugs on VHL-W117A-Venus protein stability at different length of treatment. VHL-W117A-Venus cells were treated for 8, 16, or 24 hours with the candidate drugs (10μg/ml) and MG132 (1μg/ml for 8 and 16 hours, 0.2μg/ml for 24 hours). VHL-W117A-Venus level was examined with anti-VHL antibody. Arrows designate the upper and lower bands of pVHL30. Arrow head designates pVHL19. (C) Effect of Azaguanine-8 on VHL-W117A-Venus and HIF2α levels. Parental 786-0 cells and VHL-W117A-Venus cells were treated with Azaguanine-8 (0.1μg/ml and 0.5μg/ml) for 48 hours. Antibodies are listed to the left of the blots. (D) Effect of candidate drugs on cellular localization of VHL-W117A-Venus. VHL-W117A-Venus cells were treated with the validated drugs, Azaguanine-8 (0.5μg/ml), Thioguanosine (0.5μg/ml), and Thiostrepton (7.5μg/ml), for 24 hours. At least 100 cells were examined by inverted fluorescence microscope from different fields for each sample. Representative fluorescent and phase contract images are shown.

DISCUSSION

Von Hippel Lindau disease is a devastating illness with no satisfying therapeutic options. A subset of VHL mutations possesses residual functionality, but these mutations are unstable due to their recognition by the proteostatic regulatory machinery, and are rapidly degraded.

An overarching goal of our effort was to develop a set of reagents that are capable of influencing VHL proteostasis at a number of key steps. Nascent pVHL is shuttled to the TRiC/CCT chaperonin via HSP70, where it is folded into a mature form, and where elongin C and B loading occurs [17]. Once the VBC complex is formed, it is released from TRiC and performs its function as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, as well as other key activities. Mutations in amino acids 114–119 and 148–155 interfere with TRiC binding, resulting in a failure of proper folding, and decreased VBC complex formation [17]. Mutations in amino acids 155–181 decrease elongin C binding [3], and decrease VHL’s ability to regulate HIF isoforms. Compounds that can improve the interaction between mutated pVHL and TRiC, or the loading of the elongin C and B proteins onto TRiC-bound pVHL may improve the phenotype of point-mutated VHL cells and alter disease behavior.

We developed a fluorescence signal-based high-throughput screening tool to detect compounds that upregulate intracellular levels of mutated VHL, and performed experiments to explore the functional consequences of mutated pVHL upregulation. We first hypothesized that a proteasome inhibitor would provide an effective positive control for a VHL-stability inducing agent. Indeed, both the laboratory grade MG132 and the FDA approved bortezomib were capable of upregulating pVHL levels. Further analysis of the functional consequences of proteasome inhibition did not reveal a clear impact on HIF2α levels or GLUT1 levels, suggesting a lack of functional normalization of HIF regulation despite increases in pVHL levels. Nevertheless, pVHL performs a number of other functions, including p53 stabilization[24], regulation of the primary cilium[11], and alteration of collagen IV homeostasis[12] all of which are not HIF-dependent. A clinical trial testing the efficacy of bortezomib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma was published in 2004[25], and showed significant and long-term tumor regression and control in a subset of patients. Our data raise the possibility that a genotype-phenotype correlation exists in patients with VHL-related disease who are on proteasome inhibitor therapy, and that patients harboring point mutations with residual functionality are most likely to respond to this class of agents. Further assessment of the impact bortezomib in animal xenograft models containing cell lines with diverse VHL mutations are underway to further explore this observation.

Our high throughput screen identified three compounds that consistently and robustly upregulated VHL. These include the purine derived antimetabolite chemotherapy agents 8-azaguanine and thioguanosine, as well as the thiazole antibiotic thiostrepton. Thiostrepton has recently been recognized to act as a proteasome inhibitor[26]. This is consistent with the findings we observed with MG132 and bortezomib in our initial validation studies. Additionally, the predominant nuclear localization of the VHL signal is similar in thiostrepton and MG132. It is less clear how 8-azaguanine and thioguanosine impact VHL levels. Figure 4A shows that the cellular distribution of VHL following 8-azaguanine and thioguanosine treatment are similar, with predominant cytoplasmic staining, although in the case of thioguanosine it appears that there is nuclear exclusion of VHL. Further exploration of the mechanism of action of these agents will be important for their development as tools to regulate VHL proteostasis, with potential therapeutic benefit.

A previously published screen identified 8-azaguanine as a lead compound capable of modulating HIF levels in neoplastic cells [27]. We have confirmed these findings, and further show that the presence of W117A pVHL can potentiate the effect of 8-azaguanine on HIF2α downregulation. These data suggest that further development of this pharmacophore may be of clinical value in patients with VHL or RCC, and that mutational subsets may derive particular benefit.

In conclusion, generation of the VHL-W117A-Venus containing 786-0 line is a first step in the search for compounds that perform specific actions on VHL proteostatic machinery. Larger screens and more refined VHL-substrate interaction assays are necessary to achieve our broader goal of developing a panel of VHL proteostasis modulating compounds.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Molino D, Sepe J, Anastasio P, De Santo NG. The history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Nephrol. 2006;19(Suppl 10):S119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, Stackhouse T, Kuzmin I, Modi W, Geil L, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260(5112):1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kibel A, Iliopoulos O, DeCaprio JA, Kaelin WG., Jr Binding of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein to Elongin B and C. Science. 1995;269(5229):1444–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.7660130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonergan KM, Iliopoulos O, Ohh M, Kamura T, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Kaelin WG., Jr Regulation of hypoxia-inducible mRNAs by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein requires binding to complexes containing elongins B/C and Cul2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(2):732–741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399(6733):271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292(5516):468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. 10.1126/science.1059796 1059796. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Solska E, Desai AA, Rolland F, Demkow T, Hutson TE, Gore M, Freeman S, Schwartz B, Shan M, Simantov R, Bukowski RM. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, Ravaud A, Bracarda S, Szczylik C, Chevreau C, Filipek M, Melichar B, Bajetta E, Gorbunova V, Bay JO, Bodrogi I, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Moore N. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2103–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST, Chen I, Bycott PW, Baum CM, Figlin RA. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, Barrios CH, Salman P, Gladkov OA, Kavina A, Zarba JJ, Chen M, McCann L, Pandite L, Roychowdhury DF, Hawkins RE. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):1061–1068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esteban MA, Harten SK, Tran MG, Maxwell PH. Formation of primary cilia in the renal epithelium is regulated by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(7):1801–1806. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020181. ASN.2006020181 [pii] 10.1681/ASN.2006020181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurban G, Hudon V, Duplan E, Ohh M, Pause A. Characterization of a von Hippel Lindau pathway involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, cell invasion, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1313–1319. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohh M, Yauch RL, Lonergan KM, Whaley JM, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Louis DN, Gavin BJ, Kley N, Kaelin WG, Jr, Iliopoulos O. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein is required for proper assembly of an extracellular fibronectin matrix. Mol Cell. 1998;1(7):959–968. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards FM, Crossey PA, Phipps ME, Foster K, Latif F, Evans G, Sampson J, Lerman MI, Zbar B, Affara NA, et al. Detailed mapping of germline deletions of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumour suppressor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(4):595–598. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zbar B, Kishida T, Chen F, Schmidt L, Maher ER, Richards FM, Crossey PA, Webster AR, Affara NA, Ferguson-Smith MA, Brauch H, Glavac D, Neumann HP, Tisherman S, Mulvihill JJ, Gross DJ, Shuin T, Whaley J, Seizinger B, Kley N, Olschwang S, Boisson C, Richard S, Lips CH, Lerman M, et al. Germline mutations in the Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) gene in families from North America, Europe, and Japan. Hum Mutat. 1996;8(4):348–357. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:4<348::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-3. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:4<348::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-3. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoenfeld AR, Davidowitz EJ, Burk RD. Elongin BC complex prevents degradation of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(15):8507–8512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8507. 97/15/8507 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman DE, Spiess C, Howard DE, Frydman J. Tumorigenic mutations in VHL disrupt folding in vivo by interfering with chaperonin binding. Mol Cell. 2003;12(5):1213–1224. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClellan AJ, Scott MD, Frydman J. Folding and quality control of the VHL tumor suppressor proceed through distinct chaperone pathways. Cell. 2005;121(5):739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman DE, Thulasiraman V, Ferreyra RG, Frydman J. Formation of the VHL-elongin BC tumor suppressor complex is mediated by the chaperonin TRiC. Mol Cell. 1999;4(6):1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenfeld AR, Parris T, Eisenberger A, Davidowitz EJ, De Leon M, Talasazan F, Devarajan P, Burk RD. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene protects cells from UV- mediated apoptosis. Oncogene. 2000;19(51):5851–5857. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(1):87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. 10.1038/nbt0102-87. nbt0102-87 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding Z, Liang J, Lu Y, Yu Q, Songyang Z, Lin SY, Mills GB. A retrovirus-based protein complementation assay screen reveals functional AKT1-binding partners. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(41):15014–15019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606917103. 0606917103 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0606917103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szafran AT, Szwarc M, Marcelli M, Mancini MA. Androgen receptor functional analyses by high throughput imaging: determination of ligand, cell cycle, and mutation-specific effects. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003605. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roe JS, Kim H, Lee SM, Kim ST, Cho EJ, Youn HD. p53 stabilization and transactivation by a von Hippel-Lindau protein. Mol Cell. 2006;22(3):395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.006. S1097-2765(06)00231-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondagunta GV, Drucker B, Schwartz L, Bacik J, Marion S, Russo P, Mazumdar M, Motzer RJ. Phase II trial of bortezomib for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3720–3725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.155. 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.155 22/18/3720. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandit B, Gartel AL. Thiazole antibiotic thiostrepton synergize with bortezomib to induce apoptosis in cancer cells. PLoS One. 6(2):e17110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017110. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia M, Bi K, Huang R, Cho MH, Sakamuru S, Miller SC, Li H, Sun Y, Printen J, Austin CP, Inglese J. Identification of small molecule compounds that inhibit the HIF-1 signaling pathway. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-117. 1476-4598-8-117 [pii] 10.1186/1476-4598-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]