Abstract

Background and Objectives

Astaxanthin, an orange-red carotenoid pigment, acts as a protective agent against oxidative damage to cells in vivo. The astaxanthin synthetase gene (crtS) size consists of 3995 bp. This gene has been suggested to catalyse β-carotene to astaxanthin in Phaffia rhodozyma. The aim of this research was to find any possible changes in this gene in two mutant strains, Gam1 and Gam2 (with high astaxanthin pigment production), previously created by gamma irradiation.

Materials and Methods

The astaxanthin synthetase gene sequence of Phaffia rhodozyma in the NCBI Gene bank was used to design primer. In Gam1, this gene was amplified using primers Asta F1, Asta R2, Asta F3, Asta R4. In Gam2, primers asta F1, asta R4 were used to amplify the gene. The amplified fragments were 8 sequenced using primers Asta F1, Asta R1, Asta F2, Asta R2, Asta F3, Asta R3 and Asta F4, Asta R4. Astaxanthin synthetase gene from two mutant strains, Gam1 and Gam2 were amplified using PCR. The amplified products were sequenced and aligned using the ClustalW software.

Conclusion

The comparison of this gene showed 98% and 99% similarities between the reference sequence and Gam1 and Gam2 mutant strains, respectively, whereas the comparison of this gene in Gam1 and Gam2 mutant strains showed 97% similarity. However, the deduced proteins showed 78% and 83% between the reference protein obtained from the wild type and Gam1 and Gam2, respectively. This similarity was 75% between the mutant strains.

Keywords: Astaxanthin, Phaffia rhodozyma, yeast, Astaxanthin synthetase, cytochrome P450

INTRODUCTION

Carotenoids play an important role as colorants, feed supplements, and nutraceuticals in the food, medical, and cosmetic industries. More than 600 different chemical structures have been described (1). Carotenoids in general are able to eliminate free radical-containing agents produced in the cells (2). They are terpenoids with the isopentenyl-pyrophosphate (IPP) molecules as the basic unit (3). Xanthophylomyces dendrorhous (Phaffia rhodozyma) and Haematococcus pluvialis are currently known as the main microorganisms useful for astaxanthin production at the industrial scale (4–6). Additionally, some marine bacteria, including Paracoccus sp. have been shown to be able to biosynthesize astaxanthin and are being checked as an alternative for astaxanthin production (7, 8).

Astaxanthin is an abundant carotenoid pigment responsible for the color of the flesh of many marine species by the ingestion of microorganisms that synthesize the pigment. Although more than 600 different cartenoids have been discovered from the carotenogenic microorganisms, only ß-carotene, lycopene and astaxanthin are commercially produced by microbial fermentation (9). The antioxidant activity of astaxanthin is about 100-500 times that of vitamin E (10). Its antioxidant properties have increased the industrial interest on the uses of astaxanthin in the aquaculture, chemical, pharmaceutical, and alimentary industries (11).

The proposed biosynthetic route of astaxanthin in Phaffia rhodozyma is isopentenyl- pyrophosphate (IPP) → geranyleranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) → phytoene → lycopene → β-carotene → astaxanthin. Recently, it has been published that the conversion of β-carotene into astaxanthin requires only one enzyme, astaxanthin synthetase or CrtS, encoded by crtS gene. This enzyme belongs to the cytochrome P450 protein family (12).

Two enzymatic activities convert β-carotene into astaxanthin through several biosynthetic intermediates: a ketolase which incorporates two 4-keto groups in the molecule of β-carotene, and a hydroxylase which introduces two 3-hydroxy groups. In X. dendrorhous, both activities could be together as a single enzyme (astaxanthin synthetase; CrtS) encoded by the crtS gene, which sequentially catalyzes the 4-ketolation of β-carotene followed by the 3-hydroxylation (13).

Mutagenesis by gamma rays studies in order to obtain microorganisms with the higher capabilities has been the subject of various studies e.g. in Hansenula anomala and Rhodotorula rubra, Phaffia rhodozyma and Aspergills niger (14–16). In the previous paper using gamma rays on Phaffia rhodozyma we obtained 11 mutant strains, two of which were astaxanthin overproducers (17). RAPD markers showed a relatively high polymorphism in the mutant strains (18). Here, we explain changes occurred in the key enzyme in astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway, astaxanthin synthase encoding gene (ctrS), in two astaxanthin overproducing mutant strains of Phaffia rhodozyma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was carried out from 2008-2010 at the Department of BioMedical Sciences, Women Research Center, Alzahra University. Gamma irradiation has been done at the Radiancy Applications Research Institute, Tehran, Iran. Gamma rays were used to induce mutagenesis with 1, 2, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6 and 7 kGy (18). Several mutant strains were obtained at all doses and two astaxanthin overproducing mutant strains, designated Gam1 and Gam2 were chosen and used for this study. In this paper we are reporting the findings on the structural changed occurred in astaxanthin synthase gene in these mutant strains, using PCR, sequencing and aligning sequences with the reference sequence derived from the wild type.

Yeast culture, Genomic DNA extraction

The strains were grown in YM broth medium (10 g/L glucose, 5 g/L bactopeptone, 3 g/L yeast extract, 3 g/L malt extract; Difco) at 20 °C in a shaker incubator (140 rpm) for 24h. Total DNA was isolated by a modification of the method of Chung (19). The quantity of DNA was measured by spectrophotometry at 260 and 280 nm and by electrophoresis on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel.

Primer design and astaxanthin synthetase gene amplification

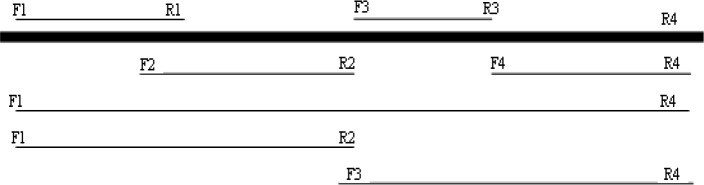

Astaxanthin synthetase gene in the reference and the mutant strain Gam1 was amplified using two pairs of primers. A pair of primers included Asta F1 as the forward primer and Asta R2 was used as the reverse primer. Other pair of primers included Asta F3 as the forward and Asta R4 as the reverse primer. Also astaxanthin synthetase gene was amplified in mutant strain Gam2 with a pair of primers, Asta F1 as the forward and Asta R4 as the reverse primer. Specific primers used for astaxanthin synthetase gene amplification are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The specific primers used for crtS gene amplification.

| Primer | Sequence | Size (bp) | Position on the crtS gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asta F1 | ATG TTC ATC TTG GTC TTG CTC | 21 | 560-580 |

| Asta R1 | AGT CTG GTT GCC TTC TTT TC | 20 | 1489-1508 |

| Asta F2 | GTG AAA AGA AGG CAA GA | 20 | 1487-1506 |

| Asta R2 | CAT GTC AAG ACT GTC GAA GAA | 21 | 2461-2482 |

| Asta F3 | CTT CGA CAG TCT TGA CAT GG | 20 | 2463-2482 |

| Asta R3 | AAA GAA GCA CAG AAG AGG AAG | 21 | 2923-2943 |

| Asta F4 | CGG CTT CCT CTT CTG TGC | 19 | 2920-2938 |

| Asta R4 | CAT TCG ACC GGC TTG ACC T | 19 | 3707-3725 |

The primers were designed according to the published sequences of astaxanthin synthetase gene. (20) with the Gen Bank accession number DQ002006. The corresponding gene fragment was amplified in the PCR reaction. Amplifications were performed in 20 µl reaction mixtures containing: 1x PCR buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris- HCl pH 9.0 and 0.5 mM MgCl2), 100 ng of genomic DNA, 160 µM of dNTPs, 0.16 µM of forward primer, 0.16 µM of reverse primer, 1.6 mM of MgCl2 and 0.4U of Taq DNA polymerase (Cinnagen, Tehran, Iran). PCR was carried out in a PTC-1148 programmable thermal controller (BioRAD, USA). The reaction for the amplification of astaxanthin synthetase gene fragment1 in mutant strain Gam1 was run for 35 cycles with the following conditions: An initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 54 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

PCR program for the amplification of astaxanthin synthetase gene fragment2 in the mutant strain Gam1 was set the same as the PCR program used for fragment1. Only the extension was set at 72 °C for 1 min and 30 s.

PCR program for astaxanthin synthetase gene amplification in the mutant strain Gam2 was run for 35 cycles with the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 54 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 3 min and 30 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 10. For sequencing, the amplified products were electrophoresed on a 0.7% (w/v) agarose gel in TBE buffer (0.89 M Tris-base pH 8.2, 0.89 M Boric acid, and 0.02 M EDTA). Gels were stained by ethidium bromide (0.5 µg/ml), visualized and photographed in a gel doc system (UVP, UK). After detection, the desired products were extracted and purified using a DNA Extraction Kit (Cinnagen, Tehran, Iran).

Finally, the obtained DNA fragments were sequenced. The amplified fragments were sequenced using primers Asta F1, Asta R1, Asta F2, Asta R2, Asta F3, Asta R3 and Asta F4, Asta R4. The position of each primeron the crtS gene has been shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 1.

The position of the pairs of primers on the crtS gene, used for PCR amplification and sequencing.

Astaxanthin synthetase gene alignment

A multiple sequence alignment for the reference and the mutant strains Gam1 and Gam2 was performed using the program ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ClustalW), and sequence identities were calculated using Gene Doc (http://www.pse.edu/biomed/genedoc).

Nucleotide sequence data were compared against the GeneBank nucleotide sequence database (BLAST search). The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/BLAST).

RESULTS

In the previous study we obtained 10 Phaffia rhodozyma mutant strains using gamma rays. Two mutant strains, Gam1 and Gam2 produced 15887.50 and 8972.02 µg/L of astaxanthin compared to the 1061.64 µg/L of the parental type (16). Based on their astaxanthin overproduction, the crtS a key gene in astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway was chosen for further studies and characterisation.

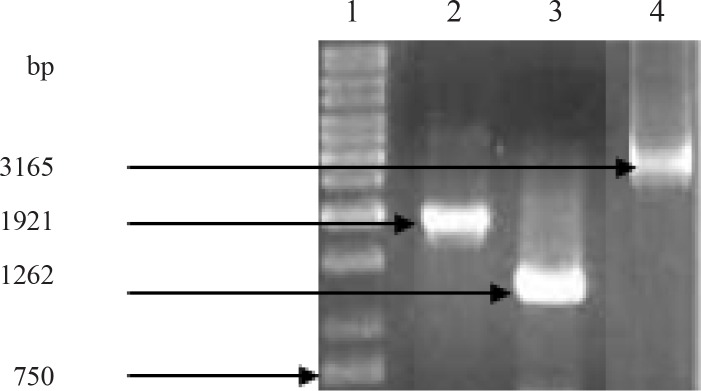

In Gam1 mutant, despite several attempts using asta F1 and asta R4 primers, the crtS gene was not amplified as a whole. Therefore, primers were designed and tried to amplify the gene sequence in two fragments. Using two pairs of primers, asta F1, asta R2 and asta F3, asta R4, two fragments of 1921 and 1262 bp were amplified, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The amplification of crtS gene. Lane 1, 1 kb ladder, lane 2 and 3 two crtS gene fragments amplified in Gam1 and lane 4, the amplification of whole crtS gene in Gam2.

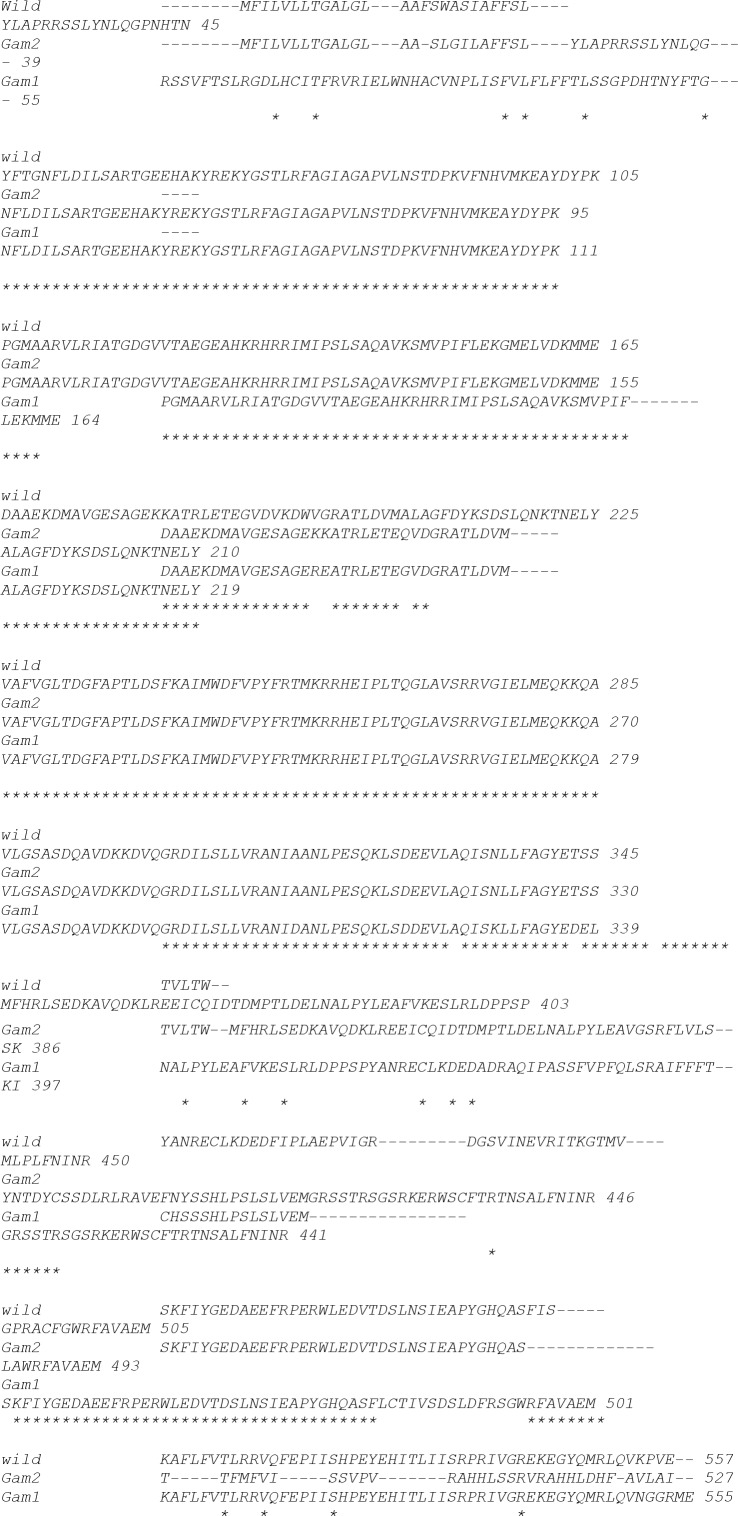

Upon sequencing of both fragments, the sequences overlapping between the two fragments were omitted and the whole sequence of the crtS gene was deduced by joining the remaining sequences in a correct order. However, in Gam2, we were able to amplify this gene (3165 123.bp) using asta F1 and asta R4 (Fig. 2). The amplified products were aligned using the ClustalW software and mutation points were identified (Fig. 3) Then a comparison was made between reference strain with the mutant strains Gam1 and Gam2 (Fig. 3). In this comparison it was determined that homology percentage of the reference sequence with the mutant strains Gam1 and Gam2 sequences was 78% and 83%, respectively and the homology percentage of the sequences between the two mutant strains Gam1 and Gam2 was 75%.

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of astaxanthin synthase gene (crtS) of the reference sequence with those of Gam1 and Gam2 mutant strains using ClustalW.

Comparison of astaxanthin synthetase gene sequence between the reference sequence and the mutant strains Gam1 and Gam2 revealed that the reference sequence differed in 22% and 17% with the mutant strains Gam1 and Gam2, respectively. It could be said that mutations occurred in almost 20% of astaxanthin synthetase gene sequence in these two mutant strains. In DNA sequence comparison, Gam1 and Gam2 strains showed 98% and 99% homology with the reference sequence and 97% homology with each other (data not shown). These two mutant strains showed a much higher astaxanthin production potential in relation to the parental type (16).

DISCUSSION

The astaxanthin synthetase gene (crtS) size consists of 3995 bp and is one of the key genes in astaxanthin biosynthesis. The product of crtS gene is suggested to have a hydroxylase-ketolase bifunctional activity in the conversion of ß-carotene to astaxanthin in Phaffia rhodozyma (12). In a complementation study of X. dendrorhous mutants and the expression analysis in Mucor circinelloides conducted by Alvarez et al. (10), it was reported that the CrtS enzyme is a beta-carotene hydroxylase of the P-450 monooxygenase family that converts beta-carotene to the hydroxylated derivatives beta-cryptoxanthin and zeaxanthin, but it does not form astaxanthin or the ketolated intermediates in this fungus. Ojima et al. (13), also cloned astaxanthin synthase gene from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. They declared that the cDNA of this beta-carotene oxygenase encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase belonging to the 3A subfamily. P450-specific domains were identified including a cytochrome P450 and an oxygen binding motif. Electrons are provided by a cytochrome P450 reductase. Functional characterisation of the enzyme by genetic modification of X. dendrorhous demonstrated that this P450 monooxygenase is multifunctional and catalyzing all steps from beta-carotene to astaxanthin formation by the oxygenation of carbon 3 and 4.

However, this idea is challenged by Alcaino et al. (12), who suggested that the conversion of beta-carotene into astaxanthin requires two enzymes, astaxanthin synthase or CrtS, encoded by crtS gene, belonging to the cytochrome P450 protein family, and the crtR gene product, from X. dendrorhous yeast, which encodes a cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) that provides CrtS with the necessary electrons for substrate oxygenation.

In this research, even though the crtS gene and the deduced proteins were shown to have been altered due to the gamma irradiation in Gam1 and Gam2 strains, but astaxanthin is being produced and even with a much higher efficiency. Considering these facts together, it is not clear for us yet that (a) these altered CrtS proteins have found a better functionality or (b) there is an alternative pathway (s) for astaxanthin biosynthesis in this yeast as proposed by An et al. (21), or (c) there may be other copies of crtS gene compensating for the altered crtS gene, as the genome sequence of Phaffia rhodozyma is not completely known, to analyze the complete transcriptome and proteome (22, 23).

Regarding the occurrence of extra copies of some genes in Phaffia rhodozyma, lines of evidence come from Medwid (24), whose findings suggested that Phaffia rhodozyma is not haploid and also from Niklitschek et al. (25), who cloned and studied the genes (idi, crtE, crtYB, crtl and crtS at their genomic and cDNA level, controlling the astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway in the wild-type ATCC 24230 strain of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. The genetic analysis of the crtYB, crtl and crtS loci in the wild-type, gave evidence of the diploid constitution of ATCC 24230 strain. In order to discover the possibility of the existence of alternative pathways or the spare copies of the genes in astaxanthin biosynthesis, we propose that site directed mutagenesis be performed on each one of the genes involved in its biosynthesis and follow astaxanthin production in the downstream.

ACKNOWELDGEMENT

This research was conducted by the joint financial support of Alzahra University and Imam Khomeini International University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takaichi S, Sandmann G, Schnurr G, Satomi Y, Suzuki A, Misawa N. The carotenoid 7,8-dihydro-ψ end group can be cyclized by the licopene cyclases from the bacterium Erwinia uredovora and the higher plant Capsicum annuum . Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0291t.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miao L, Chi S, Tang Y, Su Z, Yin T, Guan G, Li Y. Astaxanthin biosynthesis is enhanced by high carotenogenic gene expression and decrease of fatty acids and ergosterol in a Phaffia rhodozyma mutant strain. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;11:192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson E, Conklin D, Lewis M. The yeast Phaffia rhodozyma as a dietary pigment source for salmonids and crustaceans. J Fish Res Board Can. 1997;34:2417–2421. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Saiz M, de la Fuente JL, Barredo JL. Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous for the industrial production of astaxanthin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;88:645–58. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2814-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbrenner J, Linden H. Regulation of two carotenoid biosynthesis genes coding for phytoene synthase and carotenoid hydroxylase during stress-induced astaxanthin formation in the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis . Plant Physiol. 2001;125:810–817. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber RWS, Davoli P. Teaching techniques for mycology: 20. astaxanthin, a carotenoid of biotechnological importance from yeast and salmonid fish . Mycologist. 2003;17:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harker M, Hirschberg J, Oren A. Paracoccus marcusii sp. nov. an orange gram-negative coccus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:543–548. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JH, Kim YS, Choi TJ, Lee WJ, Kim YT. Paracoccus haeundaensis sp. nov., a gram-negative, halophilic, astaxanthin producing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1699–1702. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin J, Gudina E, Barredo J. Conversion of beta-carotene into astaxanthin: Two separate enzymes or a bifunctional hydroxylase-ketolase protein? Microb Cell Fact. 2008;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez VM, Rodriguez-Saiz JL, de la Fuente EJ, Gudina RP, Godio JF, Martin Barredo JL. The crtS gene of Xanthophyllomyces dendrohous encodes a novel cytochrome-P450 hydroxylase involved in the conversion of beta-carotene into astaxanthin and other xanthophylls. Fungal Genet Biol. 2006;43:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domínguez-Bocanegra AR, Ponce-Noyola T, Torres-Muñoz JA. Astaxanthin production by Phaffia rhodozyma and Haematococcus pluvialis: a comparative study. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:783–791. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0889-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alcaino J, Barahona S, Carmona M, Lozano C, Marcoleta A, Niklitschek M, Sepulveda D, Baeza M, Cifuentes V. Cloning of the cytochrome p450 reductase (crtR) gene and its involvement in the astaxanthin biosynthesis of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous . BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojima K, Breitenbach J, Visser H, Setoguchi Y, Tabata K, Hoshino T, Berg J, Sandman G. Cloning of the astaxanthin synthase gene from Phaffia rhodozyma (Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous) and its assignment as a β-carotene 3-hydroxylse/4-ketolase. Mol Gen Genomics. 2006;275:148–158. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Awan MS, Tabassam N, Ayub N, Mahboob-ur-Rahman B, Rana SM, Jajoka MI. Gamma irradiation induced mutagenesis in Aspergillus niger to enhance its microbial fermentation activity for industrial enzyme production. Mol Bio Rep. 2011;38:1367–1374. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sherbeny G, Hanafy M, Hassan A, Amin M. RAPD analysis of DNA polymorphism in the yeast Hansenula anomala and Rhodotorula rubra irradiated by gamma and fast neutrons. Int J Agr Biol. 2005;6:942–946. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun N, Lee S, Song KB. Characterization of a carotenoid-hyperproducing yeast mutant isolated by low dose gamma irradiation. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;94:263–267. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Najafi N, Ahmadi AR, Hosseini R, Golkhoo S. Gamma irradiation as a useful tool for the isolation of astaxanthin-overproducing mutant strains of Phaffia rhodozyma . Can J Microbiol. 2011;57:730–734. doi: 10.1139/w11-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Najafi N, Hosseini R, Ahmadi AR. Impact of gamma rays on the Phaffia rhodozyma genome revealed by RAPD-PCR. Iran J Microbiol. 2011;3:216–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung N. DNA preparation from 10-ml yeast culture. 1996. http://www.duke.edu/web/ceramide/protocols.

- 20.Lodato P, Alcaino J, Barahona S, Niklitschek M, Carmona M, Baeza M, Cifuentes V. Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous astaxanthin synthetase (Ast) gene, complete cds. 2005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/62906642.

- 21.An GH, Cho MH, Johnson EA. Monocyclic carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in the yeast Phaffia rhodozyma (Xanthophylomyces dendrohous) J Biosc Bioeng. 1999;88:189–193. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visser H, vanOoyen AJJ, Verdoes JC. Metabolic engineering of astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway of Xanthophylomyces dendrohous . FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;4:221–223. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lodato P, Alcaino J, Barahona S, Retamales P, Jimenez A, Cifuentes V. Study of the expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes in wild- type and deregulated strains of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (Ex.: Phaffia rhodozyma) Biol Res. 2004;37:83–93. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medwid RD. Phaffia rhodozyma is polyploidy. J Ind Microbiol Biotech. 1998;21:228–232. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niklitschek M, Alcaíno J, Barahona S, Sepúlveda D, Lozano C, Carmona M, Marcoleta A, Martínez C, Lodato P, Baeza M, Cifuentes V. Genomic organization of the structural genes controlling the astaxanthin biosynthesis pathway of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous . Biol Res. 2008;41:93–108. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602008000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]