Abstract

Background/Aims

Many patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) also present with extraesophageal symptoms (EESs). This study sought to determine the prevalence of concomitant EESs and to evaluate quality of life (QOL) impairment in a Korean population with GERD.

Methods

This questionnaire-based study was carried out from 64 hospitals in Korea between October 2008 and March 2009. Patients with typical GERD symptoms of heartburn or acid regurgitation were recruited for study. Participants filled out questionnaire consisting of GerdQ questions and EES questions. All participants underwent endoscopy and were divided into patients with erosive reflux disease (ERD) and with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD).

Results

A total of 1,712 patients were included in this study. Of these, 697 (40.7%) patients had ERD and 1,015 (59.3%) NERD. The prevalence of EES was 90.3%. The most prevalent EES was epigastric burning (73.2%), followed by globus (51.8%), chest pain (48.4%), cough (32.0%), hoarseness (24.2%) and wheezing (17.3%). Individual EES was more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD. Regarding QOL, 701 patients (41.0%) had sleep disturbance and 676 (37.7%) had taken additional over-the-counter medication for heartburn and/or regurgitation, which were more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD (49.5% vs. 35.1% and 45.8% vs. 32.2%, respectively; all P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The prevalence of EES is high in Korean patients with symptomatic GERD. Individual EES is more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD. QOL impairment is observed less frequently than previous studies.

Keywords: Extraesophageal symptom, Gastroesophageal reflux, Prevalence, Quality of life

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition which develops when the reflux of gastric content causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.1 The prevalence of GERD is usually estimated from the typical esophageal symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. A systematic review found the prevalence of GERD to be 10-20% in the Western countries with a lower prevalence in Asia.2 In Eastern Asia, however, the lifestyle and dietary habits are becoming more westernized and it is suggested that the prevalence of GERD may have been increasing.3-5

The spectrum of clinical presentations attributed to GERD has expanded from typical esophageal symptoms to an assortment of extraesophageal symptoms (EESs).1,6,7 EESs can occur concomitantly with or without typical GERD symptoms. Several studies show that many patients with GERD also present with EESs.7-12 More concerns arose from the recent data showing that the cost of caring for patients with extraesophageal reflux is even 5 times that of typical GERD in the United States.13

Although there are many reports regarding the prevalence of GERD in patients with respiratory or laryngeal symptoms, little is known regarding the prevalence of EESs in a population with GERD, especially in Eastern populations.9,14,15 Furthermore, most published estimates of EESs in patients with GERD have been derived from relatively small seriese, and in some cases prevalence of EES is concentrated on only one or individual EES.7,15-17

Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to determine the overall prevalence of concomitant EESs and to evaluate quality of life (QOL) impairment in a Korean population with symptomatic GERD. The second aim is to compare the occurrence of EES between patients with either symptomatic erosive reflux disease (ERD) or non-erosive reflux disease (NERD).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The present study is a prospective, nationwide, multicenter, observational study. The study was carried out in South Korea between October 2008 and March 2009 and involved 123 clinicians from 64 hospitals. The study population consists of patients with typical symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn or acid regurgitation manifested over the preceding week. Patients aged 20-80 years who agreed to participate in this study and to undergo upper endoscopy (or underwent upper endoscopy within the previous 6 months) were considered eligible for inclusion. The patients were not enrolled into the study if any of the following criteria were present: (1) a history of gastrointestinal surgery and/or gastroesophageal cancers, (2) continuous treatment with proton pump inhibitors or histamine 2 receptor antagonists for more than 7 days within 4 weeks prior to inclusion, (3) any "alarm symptoms," such as significant unintentional weight loss, hematemesis, melena, fever, jaundice or any other sign indicating serious or malignant diseases, (4) other significant cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, pancreatic or liver diseases, (5) pregnancy and lactation and (6) alcohol or drug addiction. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating hospitals, and all subjects were provided written informed consent before entering the study.

Symptom Assessment

Eligible patients answered the self-administrated questionnaire with 6 questions from the GERD questionnaire (GerdQ) assessment tool and 6 questions regarding EESs occurring over the preceding week. The 6 questions from GerdQ consisted of 4 questions about the gastrointestinal symptoms (2 positive and 2 negative predictors) and 2 questions about the impact of the disease.18 As for each question of GerdQ, the patient could choose 1 from 4 possible answers (none, 1 day, 2-3 days and 4-7 days), depending on the frequency of the symptoms over the past 7 days. Scores ranging from 0 to 3 were applied for the positive predictors and from 3 to 0 (reversed order, where 3 = none) for negative predictors. The GerdQ score was calculated as the sum of these scores, giving a total score ranging from 0 to 18. The list of questions used was as follows: (1) how often did you have a burning feeling behind your breastbone (heartburn); (2) how often did you have stomach content (liquid or food) moving upwards to your throat or mouth (regurgitation); (3) how often did you have pain in the center of the upper stomach; (4) how often did you have nausea; (5) how often did you have difficulty in getting a good night's sleep because of your heartburn and/or regurgitation; (6) how often did you take additional medication for heartburn and/or regurgitation, other than what the physician told you to take (such as Mylanta® and Almagel®). QOL was evaluated in terms of sleeping disturbance and requirement of additional medication for reflux symptom control using the fifth and sixth questions. Sleep disturbance was defined when the patient had difficulty in getting a good sleep at least once a week.

To evaluate EESs in Korean patients with GERD, 6 symptoms were determined on the basis of the opinions of Korean experts in GERD: epigastric burning, cough, wheezing, globus, hoarseness and chest pain. As for the GerdQ questionnaire, patients were asked to check 1 of the 4 possible answers (none, 1 day, 2-3 days and 4-7 days), depending on the frequency of symptoms over the past 7 days. Scores ranging from 0 to 3 were applied for each question. The EES score was calculated as the sum of these scores, giving a total score ranging from 0 to 18. The list of questions used was as follows: (7) how often did you have epigastric burning; (8) how often did you have cough; (9) how often did you have wheezing; (10) how often did you have globus; (11) how often did you have hoarseness; and (12) how often did you have chest pain.

Data Collection

The questionnaire required details of gender, age, height and weight, and smoking status. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared (kg/m2). Smoking status was divided into current smoker, ex-smoker and non-smoker.

The endoscopic results were requested to classify the findings of the lower esophagus, according to the Los Angeles (LA) classification as follows: normal, minimal change lesion, and LA classification A to D.19 All participants were divided into patients with ERD and those with NERD according to the presence of reflux esophagitis defined by endoscopy. Web-based case report form was used to collect the patients' data.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS statistical package 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t test for parametric method or Mann-Whitney's U test for nonparametric methods. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. The frequency of EES and EES score were compared according to each following variable: gender (male vs. female); age (< 50 yr vs. ≥ 50 yr); smoking status (current smoker vs. ex-smoker/non-smoker); BMI (< 25 kg/m2 vs. ≥ 25 kg/m2); and reflux esophagitis (ERD vs. NERD). A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population

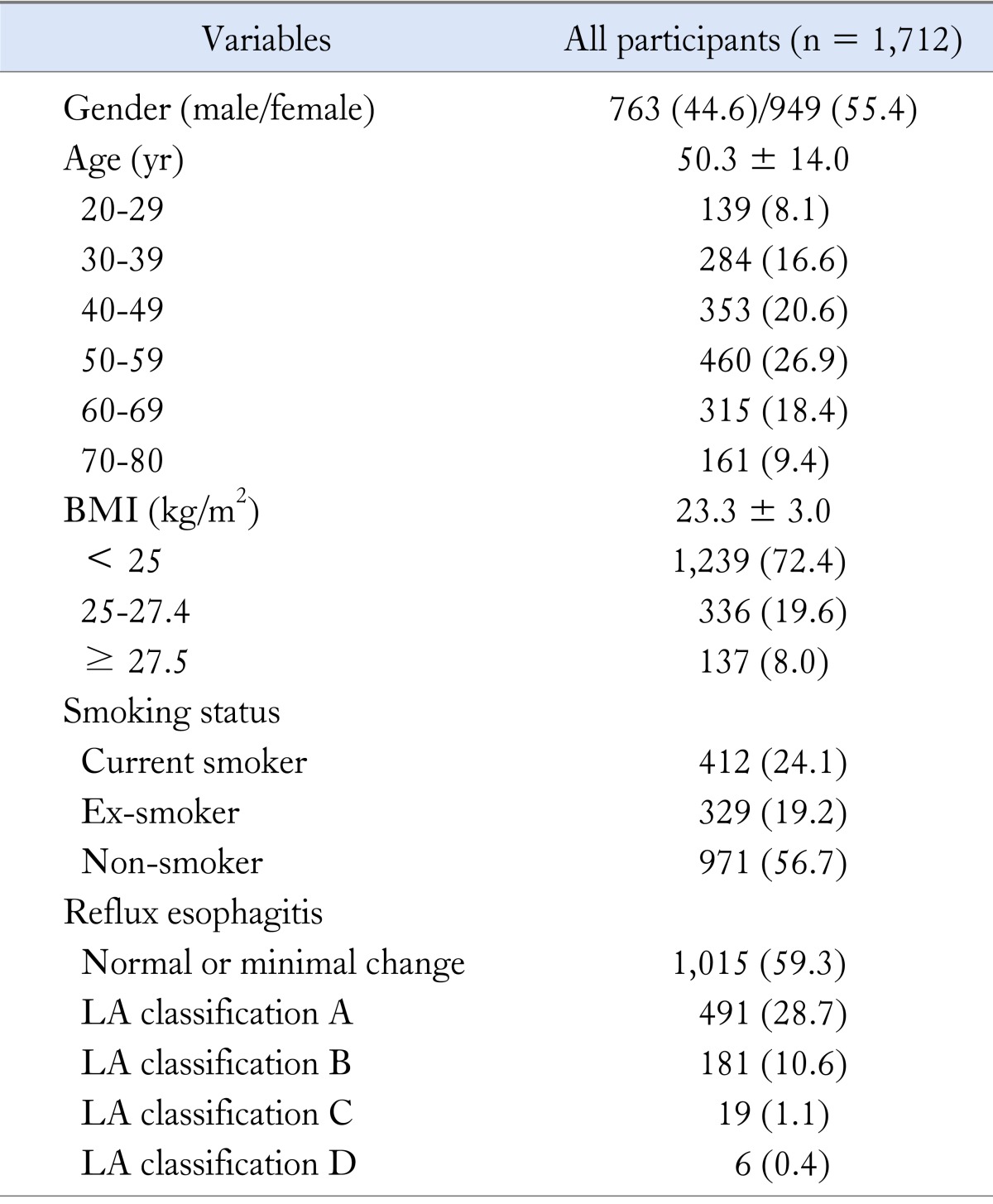

A total of 1,712 patients were included in this study. Of these, 763 patients (44.6%) were male and the mean age was 50.3 ± 14.0 (SD) years. The mean BMI was 23.3 ± 3.0 kg/m2: 1,239 patients (72.4%) had BMI < 25 kg/m2, 336 (19.6%) BMI 25-27.4 kg/m2 and 137 (8.0%) BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2. In terms of smoking, 412 patients (24.1%) were current smokers, 329 (19.2%) ex-smoker and 971 (56.7%) non-smoker. Normal or minimal change lesion on endoscopy in the lower esophagus (NERD) was shown in 1,015 patients (59.3%), while 697 (40.7%) had reflux esophagitis (ERD). Of the total study population, 491 patients (28.7%) were reflux esophagitis, LA-A, 181 (10.6%) LA-B, 19 (1.1%) LA-C and 6 (0.4%) LA-D. Baseline characteristics and endoscopic findings at inclusion are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

BMI, body mass index; LA, Los Angeles.

Data are shown as the mean ± SD or number (%) of subjects.

The Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire Assessment

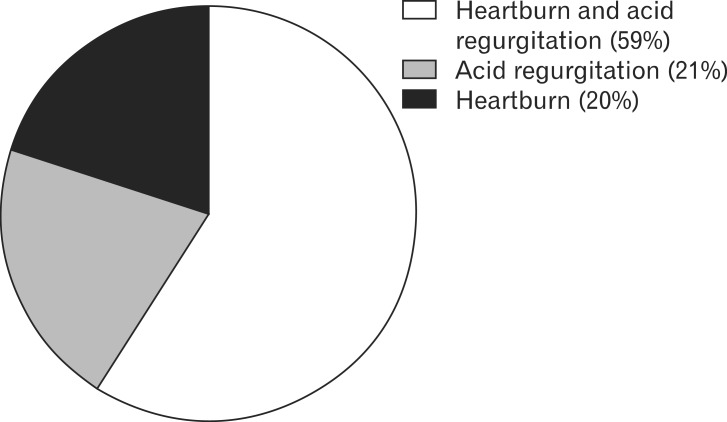

The mean GerdQ score was 6.86 ± 3.67. Regarding the typical GERD symptoms, 1,003 patients (58.6%) had both heartburn and acid regurgitation, 348 (20.3%) heartburn and 361 (21.1%) acid regurgitation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of typical gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in the study population.

Regarding the impacts of the disease, 701 patients (41.0%) answered that they have difficulty in getting a good night's sleep because of their heartburn and/or regurgitation over the past week. Sleep disturbance was more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD (49.5% vs. 35.1%, P < 0.001). Six hundred seventy-six patients (37.7%) answered that they have taken additional medication for their heartburn and/or regurgitation, other than what the physician told them to take over the past week. Over-the-counter medication was also more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD (45.8% vs. 32.2%, P < 0.001).

Evaluation of Extraesophageal Symptoms

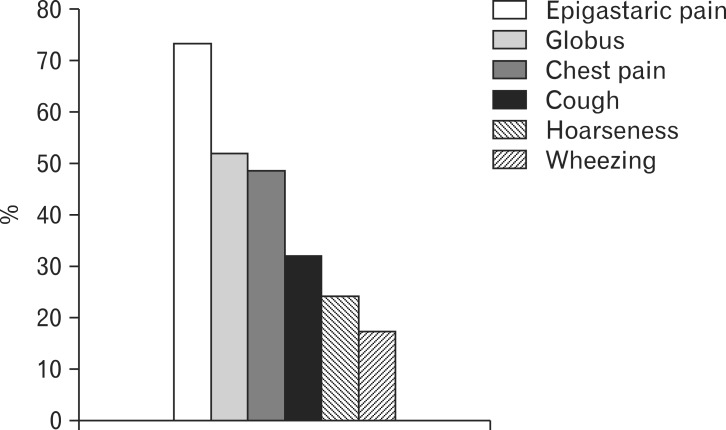

One thousand five hundred forty-five patients (90.3%) presented at least one EES among 6 symptoms over the past week. The most prevalent EES was epigastric burning (73.2%), followed by globus (51.8%), chest pain (48.4%), cough (32.0%), hoarseness (24.2%) and wheezing (17.3%) (Fig. 2). Of the 1,545 patients with EES, 292 patients (18.9%) were presented with EESs in 1 day over the past week, 666 (43.1%) in 2-3 days and 587 (38.0%) in 4-7 days. The prevalence of EES excluding epigastric burning in this study was 74.7%.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of individual extraesophageal symptom in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

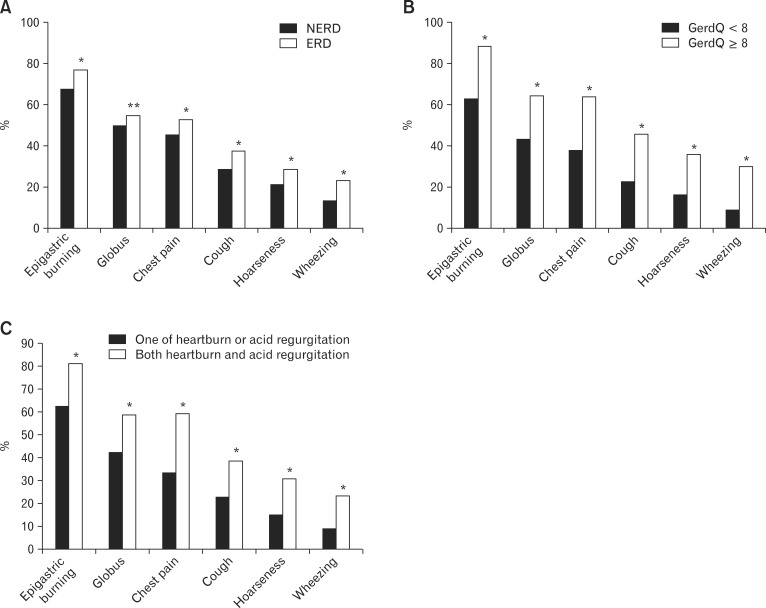

The prevalence of EES did not differ regardless of gender (male vs. female), age (< 50 yr vs. ≥ 50 yr), smoking status (current smoker vs. ex-smoker/non-smoker), BMI (< 25 kg/m2 vs. ≥ 25 kg/m2) and reflux esophagitis (ERD vs. NERD). However, individual EES was more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD (Fig. 3A). In addition, individual EES was more prevalent in patients presenting with both typical GERD symptoms than in those with a single typical GERD symptom and in patients with GerdQ score ≥ 8 than in those with GerdQ score < 8 (Fig. 3B and 3C).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the prevalence of individual extraesophageal symptom (EES) between subgroups: individual EES is more prevalent (A) in patients with erosive reflux disease (ERD) than in patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), (B) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire (GerdQ) score ≥ 8 than in patients with GerdQ score < 8, and (C) in patients presenting both typical gastroesophagealreflux disease symptoms than in patients presenting one. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05

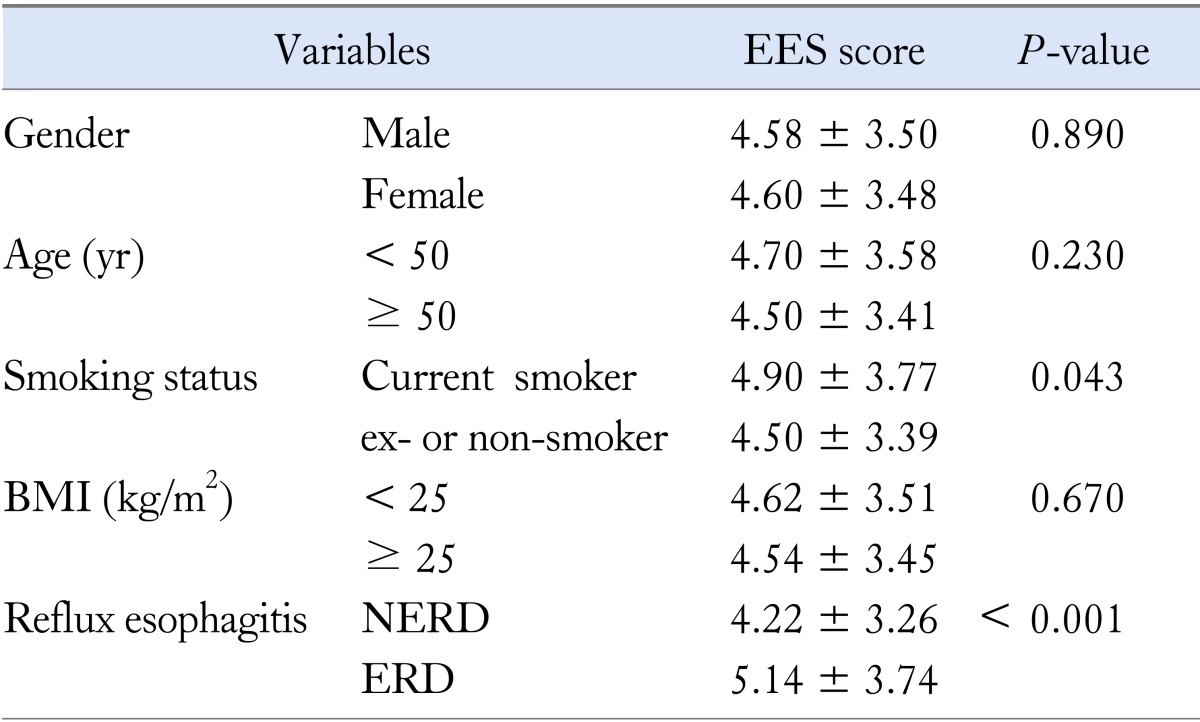

The mean EES score was 4.59 ± 3.49. The EES score was higher in current smokers than ex- or non-smokers (4.90 ± 3.77 vs. 4.50 ± 3.39, P = 0.043) and in patients with ERD than in those with NERD (5.14 ± 3.74 vs. 4.22 ± 3.26, P < 0.001) as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Extraesophageal Symptom Score by Gender, Age, Smoking Status, Body Mass Index and Reflux Esophagitis

EES, extraesophageal symptom score; BMI, body mass index; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; ERD, erosive reflux disease.

Discussion

GERD is an acid-based disorder that presents with a wide spectrum of symptoms. In 2006, an international Consensus Group defined GERD as "a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications."1 Historically, GERD is defined as primary complaints of heartburn and regurgitation; however, it is now recognized that a range of EESs may be its sole or accompanying manifestation.1,6,7 EESs can occur concomitantly with or without typical GERD symptoms. Recent data indicate that many patients with GERD also present with EESs.7-12 However, little is known regarding the prevalence of EESs in a population with GERD, although there are many reports regarding the prevalence of GERD in patients with respiratory or laryngeal symptoms.9,14,17 Especially, in Eastern countries, data on the prevalence of EESs in patients with GERD is largely lacking.15,20 Concerning the differences in epidemiology in Asia compared to Western populations and increasing awareness and recognition of EES of GERD, it is needed to establish the prevalence of EESs in patients with GERD in Korea.21

The present study investigated the prevalence of EESs in a Korean population with typical GERD symptoms using the self-administrated questionnaire. Of the 1,712 participants with heartburn and/or acid regurgitation manifested over the preceding week, EES was detected in 1,545 patients (90.3%) and EES excluding epigastric burning in 1,274 (74.4%). There was no difference in the prevalence of EES between patients with ERD and those with NERD, which is consistent with that of previous Asian study by Yi et al.22 However, individual EES was more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD, while Yi et al22 reported similar frequencies of atypical symptoms between ERD and NERD patients. This discrepancy may be explained by the different study population enrolled. The patients of present study had typical reflux symptoms at least once a week and were not evaluated with impedance pH monitoring or proton pump inhibitor trial, while the patients of the study by Yi et al22 had typical reflux symptoms occurring at least 3 times weekly and were responsive to proton pump inhibitor or histamine 2 receptor antagonist. As a result, more patients with functional heartburn could have been included in patients with NERD in the present study than in those of the study by Yi et al.22 This possible, misclassified patients group may cause underestimation of the prevalence of EES in patients with NERD in this study.

In this study, EES was frequently observed in patients with GERD. Previous studies showed varying estimates of EES in patients with GERD, depending on the population studied. In a population-based study performed in 2,200 residents from Olmsted County, Minnesota, at least one atypical GERD symptom was present in 80% of the subjects presenting with heartburn and/or acid regurgitation weekly, while it was present in only 49% of those without heartburn and acid regurgitation.14 In this study, chest pain was the most prevalent EES and dysphagia, dyspepsia and globus sensation were followed. However, GERD symptoms were not associated with asthma, hoarseness, bronchitis or a history of pneumonia. In the prospective, open cohort study involving more than 6,000 GERD patients from Germany, Austria and Switzerland, the prevalence of EESs in patients with typical esophageal symptoms was 32.8%.9 In the same study, chest pain was the most common EES (14.5%), followed by chronic cough (13%), laryngeal disorder (10.4%) and asthma (4.8%). These observations provide us a clue that the prevalence of EES and the frequency of individual EES are different depending on populations. In addition, we could suggest that epigastric burning and globus are the most common EESs in Korean GERD patients, which is different from Western populations.

Epigastric burning was included as an EES in this study by the opinions of experts in GERD. However, it might be debatable whether the epigastric burning is an EES of GERD or not. Epigastric burning is also a symptom of functional dyspepsia (FD).23 Many patients with FD do not complaint of pain, but rather state that they have burning, pressure or fullness in the epigastric area, or cannot finish a normal-sized meal. GERD and FD are the most prevalent upper gastrointestinal disorders. Not surprisingly, given the high prevalence of both disorders, symptoms of GERD and FD frequently coexist and overlap.24 Nevertheless, predominant symptoms of GERD effectively exclude a diagnosis of FD according to the Rome III criteria.23 Therefore, epigastric burning in patients with symptomatic GERD could be considered as an EES.

The true prevalence of EES in patients with GERD is difficult to determine, because it is difficult to evaluate whether GERD is causing the EES or whether the 2 conditions coexisting dependently from each other. In addition, the lack of a control group with EES but without GERD is one drawback. However, our results show that individual EES is more prevalent in patients presenting both typical GERD symptoms than in those with a single typical GERD symptom, and in patients with GerdQ score ≥ 8 than in those with GerdQ score < 8. The EES score is higher in patients with ERD than in those with NERD. This observations are consistent with that of previous studies,9,25 and therefore we could conclude that GERD appears to contribute to the occurrence of EES and that patients with ERD suffer from a more EESs than those with NERD. However, EES score used in the present study was not validated for its accuracy and reproducibility. Therefore, our results need to be interpreted in the context of this limitation.

In a recent systemic review on the burden of GERD on QOL, patients with disruptive GERD (frequent symptom ranging from daily to ≥ weekly) had an increase in time off work and decrease in work productivity. Low scores on sleep scales were seen compared with patients with less frequent symptoms.26 Nocturnal GERD has a greater impact on QOL compared with daytime symptoms. Both nocturnal symptoms and sleep disturbances are critical in evaluating the GERD patient.27 In this study, QOL impairment was assessed by GerdQ. Sleep disturbance due to heartburn and/or regurgitation was observed in 41.0% of patients and more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD. Previous studies reported sleep disturbances affected by reflux in 63-65% of GERD patients.28,29 This discrepancy of frequency of sleep disturbance could be explained by relatively common NERD patients in Korea and by the different definition of sleep disturbance in each study. In addition, 37.7% of patients had taken additional over-the-counter medication for their heartburn and/or regurgitation in this study, which might reduce sleep disturbances through reflux symptom control.

In conclusion, the prevalence of EES is high in Korean patients with symptomatic GERD. Individual EES is more prevalent in patients with ERD than in those with NERD. Sleep disturbances were observed less frequently than previous studies. QOL impairment is more frequently observed in patients with ERD than in those with NERD.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by AstraZeneca Korea (Grant No. PHO3081591).

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Yang Won Min contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript; Seong Woo Lim contributed to data analysis and interpretation; Jun Haeng Lee Hang provided data and contributed to data analysis and interpretation; Hang Lak Lee, Oh Young Lee, Jae Myung Park and Myung-Gyu Choi provided data and performed critical revision; Poong-Lyul Rhee designed and coordinated the study, contributed to data interpretation and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong BC, Kinoshita Y. Systematic review on epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai Y, Du Y, Zou D, et al. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire (GerdQ) in real-world practice: a national multicenter survey on 8065 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:626–631. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho YK, Kim GH, Kim JH, et al. [Diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review.] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:279–295. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.5.279. [Korean] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havemann BD, Henderson CA, El-Serag HB. The association between gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and asthma: a systematic review. Gut. 2007;56:1654–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.el-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A. Comorbid occurrence of laryngeal or pulmonary disease with esophagitis in United States military veterans. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:755–760. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gislason T, Janson C, Vermeire P, et al. Respiratory symptoms and nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study of young adults in three European countries. Chest. 2002;121:158–163. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaspersen D, Kulig M, Labenz J, et al. Prevalence of extra-oesophageal manifestations in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: an analysis based on the ProGERD Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1515–1520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ours TM, Kavuru MS, Schilz RJ, Richter JE. A prospective evaluation of esophageal testing and a double-blind, randomized study of omeprazole in a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for chronic cough. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3131–3138. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field SK, Sutherland LR. Does medical antireflux therapy improve asthma in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux?: a critical review of the literature. Chest. 1998;114:275–283. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fass R, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux disease - current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hom C, Vaezi MF. Extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:71–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SH, Choi MG, Park SH, et al. [The clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korea.] Korean J Gastrointest Motil. 2000;6:1–10. [Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ing AJ, Ngu MC, Breslin AB. Chronic persistent cough and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Thorax. 1991;46:479–483. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.7.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waring JP, Lacayo L, Hunter J, Katz E, Suwak B. Chronic cough and hoarseness in patients with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. Diagnosis and response to therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1093–1097. doi: 10.1007/BF02064205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, et al. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugawa T, Fujiwara Y, Okuyama M, et al. [Prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of extraesophageal manifestations of GERD.] Nihon Rinsho. 2007;65:946–950. [Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fock KM, Talley NJ, Fass R, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:8–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi CH, Liu TT, Chen CL. Atypical symptoms in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:278–283. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quigley EM, Lacy BE. Overlap of functional dyspepsia and GERD-diagnostic and treatment implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Räihä I, Hietanen E, Sourander L. Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1991;20:365–370. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tack J, Becher A, Mulligan C, Johnson DA. Systematic review: the burden of disruptive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1257–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerson LB, Fass R. A systematic review of the definitions, prevalence, and response to treatment of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaker R, Castell DO, Schoenfeld PS, Spechler SJ. Nighttime heartburn is an under-appreciated clinical problem that impacts sleep and daytime function: the results of a Gallup survey conducted on behalf of the American Gastroenterological Association. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1487–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yi CH, Hu CT, Chen CL. Sleep dysfunction in patients with GERD: erosive versus nonerosive reflux disease. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334:168–170. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318141f4a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]