Abstract

Objectives

To assess the proportion of patients lost to programme (died, lost to follow-up, transferred-out) between HIV diagnosis and start of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa, and determine factors associated with loss to programme.

Methods

Systematic review and meta-analysis. We searched PubMed and EMBASE databases for studies in adults. Outcomes were the percentage of patients dying before starting ART, the percentage lost to follow-up, the percentage with a CD4 cell count, the distribution of first CD4 counts and the percentage of eligible patients starting ART. Data were combined using random-effects meta-analysis.

Results

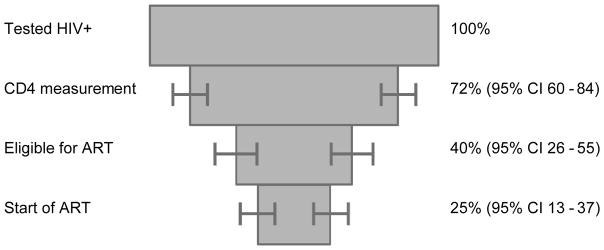

29 studies from sub-Saharan Africa including 148,912 patients were analysed. 6 studies covered the whole period from HIV diagnosis to ART start. Meta-analysis of these studies showed that of 100 patients with a positive HIV test, 72 (95% CI 60–84) had a CD4 cell count measured, 40 (95% CI 26–55) were eligible for ART and 25 (95% CI 13–37) started ART. There was substantial heterogeneity between studies (p<0.0001). Median CD4 cell count at presentation ranged from 154 cells/μl to 274 cells/μl. Patients eligible for ART were less likely to become lost to programme (25% versus 54%, p<0.0001) but eligible patients were more likely to die (11% versus 5%, p<0.0001) than ineligible patients. Loss to programme was higher in men, in patients with low CD4 cell counts and low socio-economic status, and in recent time periods.

Conclusions

Monitoring and care in the pre-ART time period needs improvement, with greater emphasis on patients not yet eligible for ART.

Keywords: pre-ART, linkage to care, sub-Saharan Africa, mortality, loss to follow-up

Introduction

Attrition of HIV infected patients in care before starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) is high in low-income settings (Amuron et al. 2009, Bassett et al. 2009). However, much research has focused on clinical outcomes of ART, while few studies have analysed loss to programme (i.e. due to mortality, loss to follow-up or transfer-out to another site) between HIV testing and ART initiation. Clinical documentation is often poor or non-existent during this time period. Healthcare systems are overloaded, testing might take place at a different site than the provision of ART, and patients ineligible for ART are less sick and do not require monitoring of ART-related side effects. A recent systematic review showed substantial variation in loss to programme across sites, but did not distinguish between loss to follow-up, mortality and transfer-out (Rosen & Fox 2011). Only two studies covered the whole time period from diagnosis of HIV infection to ART initiation (Kranzer et al. 2010, Tayler-Smith et al. 2010), and predictors of loss to programme were not explored.

Despite the fact that ART coverage in sub-Saharan Africa has increased substantially in recent years, and had reached 6.6 million people by the end of 2010, approximately 9 million people remain untreated (WHO 2011). The majority of the patients who start ART do so too late with low CD4 cell counts and opportunistic infections (Keiser et al. 2008, Fairall et al. 2008, Kigozi et al. 2009). As a result, mortality in the first few months after therapy start is also high (May et al. 2010, Braitstein et al. 2006).

If the reasons for patient attrition between diagnosis and beginning of ART were known, programmes could plan more efficiently and better allocate their resources. ART coverage would be increased, and early mortality on ART would be reduced. Our goal was to ascertain why patients are lost to programme before they begin ART. We therefore performed a systematic review to determine the magnitude and predictors of mortality, loss to follow-up and transfer-out between HIV diagnosis and start of antiretro-viral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Data sources

We searched PubMed and EMBASE databases on August 9th 2011, limiting the search to studies in humans, studies from sub-Saharan Africa and to English-language publications. We also limited the search to studies that were published after 2001, because ART scale up in resource-limited settings began in 2002 (Keiser et al. 2008, Gilks et al. 2006). We used both free text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and a combination of the following words and their variations: antiretroviral agents, therapeutic use, pre treatment, pre-ART, prior to treatment, eligibility, loss to care and loss to follow-up. We examined the references of all included studies. Further details of the search strategy are given in the web appendix.

Study selection

We included all studies that reported on numbers of participants followed between HIV diagnosis and start of ART, including studies that did not cover the entire period. We excluded studies on children and on the prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT). We also excluded qualitative studies and reports from national programmes. Studies that reported on specific topics that were not the primary area of interest (i.e. modelling studies without primary data, studies on drug resistance, adherence or drug interactions, cancer-specific studies or studies on pre-ART HIV transmission) were also excluded. We used no other selection criteria. Two reviewers (CM, OK) independently assessed the eligibility of articles and abstracts. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

To minimise transcription errors, we used a double entry system to enter data from each publication into a standardised extraction sheet. The following data were extracted: eligibility criteria of participants, the characteristics of the programme (setting, location, country), characteristics of participants (age, gender and CD4 cell count at different time points), eligibility criteria for ART start, methods for tracing patients lost to follow-up and the number of patients alive and lost to programme (i.e. lost to follow-up, transferred out and dead) at different time points. We selected four time points: (i) HIV testing, (ii) CD4 testing with eligibility assessment for ART, (iii) becoming eligible for ART and (iv) start of ART. These defined three time periods: Stage 1 (HIV testing to CD4 testing), Stage 2 (CD4 testing to ART eligibility) and Stage 3 (ART eligibility to ART start). We extracted loss to programme, mortality, loss to follow-up and transfer-out at each stage before the initiation of ART. In addition we extracted the length of time between these time points and mortality rates in the different stages. Further we also extracted predictors for loss to programme, mortality and loss to follow-up between HIV and CD4 testing and between meeting eligibility criteria for ART and ART start. We recorded if there was a significant (p<0.05) positive or negative association or if there was no significant association. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Data were entered into an EpiData database (version 3.1.).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the percentage of people who reached each of the four time points, and combined data from relevant studies using random-effects meta-analysis on the logit scale. Combined estimates were transformed back to percentages. Because results were heterogeneous, we both calculated approximate prediction intervals (PrI) based on the whole random-effects distribution, and traditional 95% confidence intervals (CI) around the mean of the distribution. PrI predict the likely mean percentages in new studies and are the most sensible way to summarize the results of heterogeneous studies (Higgins et al. 2003). We examined sources of heterogeneity using meta-regression for treatment-eligible patients starting ART (stage 3; the only stage for which enough estimates were available). We considered the following study characteristics: country (South Africa versus others); degree of urbanisation (rural, urban, semi-urban); mode of entry into programme (voluntary counselling and testing, provider initiated counselling and testing, entry through Tuberculosis (TB) or sexually transmitted disease clinic); programme costs (free versus fee for service); ART eligibility criteria (≤200 versus >200 cells/μl); age (median age at baseline); gender (percentage female at baseline); and study period (1.1.2001–31.12.2003, 1.1.2004–31.12.2006, ≥1.1.2007). Data were analysed using STATA version 11.2 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Results

Study characteristics

We identified 81 potentially eligible full text articles out of 2,122 identified studies, based on titles and abstracts. After screening the full text articles, we included 29 studies of 148,912 treatment naïve patients. 25 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Four studies were excluded because they reported on the same study population and time period as another article that was published later (Kaplan et al. 2008, Larson et al. 2010a, Lawn et al. 2005, Losina et al. 2010). The selection of the studies is shown in detail in a flowchart in the web appendix (Figure S1).

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 29 studies included in our review. The majority (n=16) were single site studies of public-sector ART programmes; 14 were performed in South Africa. 22 studies included patients from the general population and 11 were performed in urban sites only. 10 studies reported on ART eligible participants, 15 on eligible and not yet eligible participants and 2 only on patients not yet eligible for ART. Eligibility criteria for ART differed between studies. A CD4 threshold of 200 cells/μl was most commonly used (n=18). Other CD4 thresholds were 250 (n=4) and 300 cells/μl (n=1). Two studies did not report on eligibility. The definition of LTFU also varied: “missing appointments for more than 1 month” or “no visit at the clinic for 6 or 12 months” was used in several studies (Table 1). Phone calls, home visits or linkage to the death registry were used to ascertain deaths among patients lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in review, first CD4 cell count measurement after HIV diagnosis and mortality rates prior to initiation of antiret-roviral therapy (ART)

| Study | Location | Setting | Study Period | Population | No patients ART naive | Eligibility criteria: CD4 cell count/WHO stage | Eligibility status of subjects | Definition of loss to follow-up | Tracing of patients lost to follow-up/ascertainment of vital status | First CD4 cell count; median (IQR) | pre-ART mortality rate (per 100 person years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amuron et al. (2009) | Jinja, Uganda | Rural, semi-rural | 2004 – 2007 | General | 4321 | <200/μl III and IV |

Eligible and not yet eligible | Eligible participants not starting ART until 12/2007 | Visits | 222 (111–338)° | n.r. |

| Bassett et al. (2010) | 2 facilities in Durban, South Africa | Semi-rural, urban | 2006 – 2009 | General | 1477 | <200/μl | Eligible and not yet eligible | Not reachable 6–12 months after enrolment | Phone calls | n.r. | n.r. |

| Bassett et al. (2009) | Durban, South Africa | Urban | 2006 – 2006 | General | 501 | <200/μl III and IV |

Eligible | Not starting ART ≥ 3 months of scheduled ART training appointment | Phone calls | 159 (65–299) | n.r. |

| Geng et al. (2010) | Mbarara, Uganda | Rural | 2009 – 2010 | General | 1309 | <250/μl | Eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Ingle et al. (2010) | 28 facilities in Freestate Province, South Africa | Rural, semi-rural, urban | 2004 – 2008 | General | 44844 | <200/μl IV |

Eligible and not yet eligible | No visit, length depending on CD4 cell count | Linkage to death registry | 170 (76–318) | 53.2*, 32.4& |

| Kaplan et al. # (2008) | Cape Town, South Africa | Urban | 2002 – 2007 | Women only | 2131 | n.r. | Eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Kohler et al. (2011) | Nairobi, Kenya | Urban. | 2005 – 2008 | General | 5854 | <250/μl III an IV |

Eligible and not yet eligible | No return to clinic > 30 Days after scheduled appointment | Phone calls | n.r. | n.r. |

| Kranzer et al. (2010) | 2 facilities in Cape Town, South Africa | Semi-rural | 2004 – 2009 | Random sample | 988 | <200/μl | Eligible and not yet eligible | No CD4 cell count within 6 months of HIV test, no ART initiation within 6 months of CD4 cell count | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Larson et al. # (2010a) | Johannesburg, South Africa | Urban | 2007 – 2009 | General | 356 | <200/μl | Not yet eligible | No return ≥52 weeks | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Larson et al. (2010b) | Johannesburg, South Africa | Urban | 2008 – 2009 | General | 389 | <200/μl | Eligible and not yet eligible | No completed CD4 test ≤ 6 weeks, 6–12 weeks, ≤ 12 weeks | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Lawn et al. (2006) | Cape Town, South Africa | Urban | 2002 – 2005 | General | 1235 | <200/μl IV |

Eligible | Only for subjects on ART | n.r. | n.r. | 33.6 |

| Lawn et al. # (2005) | Cape Town, South Africa | Semi-rural | 2002 – 2005 | General | 712 | <200/μl IV |

Eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Lessells et al. (2011) | 16 facilities in Kwa-Zulu-Natal, South Africa | Rural | 2007–2009 | General, with CD4 cell count >200/μl | 4223** | <200/μl IV |

Not yet eligible | No CD4 cell count ≤ 13 months of HIV test | Linkage to African Demographic Info System | n.r. | n.r. |

| Losina et al. # (2010) | 2 facilities in Durban, South Africa | Rural, semi-rural, urban | 2006 – 2007 | General | 454 | <200/μl | n.r. | No CD4 cell count ≤8 weeks of HIV test | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Loubiere et al. (2009) | 27 facilities in Cameroon | n.r. | 2006 – 2007 | Random sample | 180 | <200/μl IV |

Eligible and not yet eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| McGrath et al. (2010) | Karonga, Malawi | n.r. | 2005 – 2006 | General | 730 | <250/μl III and IV |

Eligible and not yet eligible | Eligible participants not starting ART | Visits | n.r. | n.r. |

| McGuire et al. (2010) | 11 facilities in Chiradzulu, Malawi | Rural | 2004 – 2007 | General | 1561 | n.r. | Eligible and not yet eligible | Missed appointment > 1 month | Visits | n.r. | n.r. |

| Micek et al. (2009) | 14 facilities in Beira and Chimoio, Mozambique | Urban | 2004 – 2006 | General | 3950 | <200/μl IV III and CD4 < 350/μl |

Eligible and not yet eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Mulissa et al. (2010) | Arba Minch, Ethiopia | Rural, urban | 2003 – 2009 | General | 2191 | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | 13.1 & |

| Murphy et al. (2010) | Durban, South Africa | Urban | 2006 – 2007 | Patients presenting with opportunistic infection (OI) | 49 | <200/μl IV |

Eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Ochieng-Ooko et al. (2010) | 23 facilities in Kenya | n.r. | 2001 – 2007 | General | 50275 | n.r. | Eligible and not yet eligible | No return > 6 months if not on ART | n.r. | Women: 225 (98–408) Men: 154 (57–302) |

n.r. |

| Pepper et al. (2011) | Cape Town, South Africa | Urban | n.r. | TB infected HIV+ | 176 | <200μl IV without extrapulmonary TB |

Eligible and not yet eligible | Not traceable after 6 months of starting TB treatment | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Scott et al. (2011) | 133 facilities in Cape Town, South Africa | Urban | 2010 | General | n.r. | n.r. | Eligible and not yet eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Tayler-Smith et al. (2011) | 3 facilities in Kibera, Kenya | Urban | 2005 – 2008 | General | 2471 | <200/μl IV and III III with CD4<350/μl |

Eligible | Missed appointment > 1 month | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Tayler-Smith et al. (2010) | Thyolo District, Malawi | Rural | 2008 – 2009 | General | 1633 | <250/μl III and IV |

Eligible and not yet eligible | n.r. | n.r. | 246 (133–414) | n.r. |

| Togun et al. (2011) | Banjul, The Gambia | Rural, urban | 2004 – 2010 | General | 790 | <200μl | Eligible | Missed appointment > 90 days | Visits, Interviews | n.r. | 21.9 |

| Van der Borght et al. (2009) | 16 facilities in Nigeria, Burundi, Rwanda, Dem. Rep. Congo, Congo | n.r. | 2001 – 2007 | Heineken employees and families | 428 | <300/μl IV CDC stage C |

Eligible and not yet eligible | n.r. | n.r. | 274 (139–435) | 1.6 |

| Zachariah et al. (2011) | Nairobi, Kenya and Thyolo Malawi | Rural, urban | 2004 – 2008 | General | 14942 | <200ul for Malawi also: III or IV and CD4<250/μl |

Eligible | Eligible patients missed appointment >= 1 month (appointments >2 months apart) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Zachariah et al. (2006) | Thyolo District, Malawi | Rural | 2003 – 2004 | Registered for TB treatment | 742 | III and IV | Eligible | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

most recent year (2006)

excluded from meta-analysis

overall pre-ART mortality rate

for eligible patients

only 930 were traced

TB Tuberculosis; WHO World Health Organization; n.r. not reported; IQR interquartile range; CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

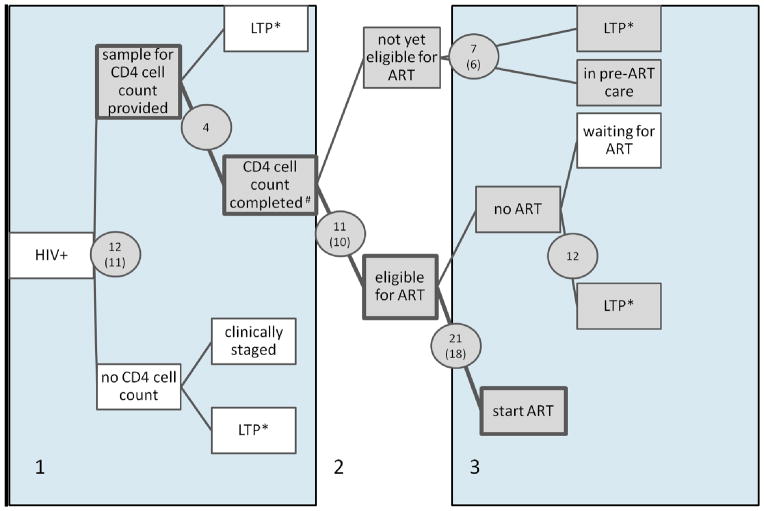

Figure 1 shows the number of studies that reported on different time periods between HIV diagnosis and ART start. Six studies, conducted in four different countries covered the whole time period (Bassett et al. 2010, Ingle et al. 2010, Kranzer et al. 2010, Micek et al. 2009, Tayler-Smith et al. 2010, Kohler et al. 2011) from HIV testing to start of ART. Most studies provided information for the time between ART eligibility and ART start (21 studies, 18 included in meta-analysis). Only a few studies reported on outcomes of patients without CD4 cell counts and on outcomes of patients not yet eligible for ART.

Figure 1.

Routes from HIV testing to start of antiretroviral therapy. Shaded boxes show the different pre-ART care points, and shaded circles show the number of studies included in the systematic review (number of studies included in the meta-analysis in parentheses) at each of these stages. The three areas (number 1 to 3) represent the different stages in the cascade which are described in more detail in the text (i.e. stage 1: From HIV to CD4 testing; stage 2: eligibility assessment; stage 3: from eligibility to start of ART). #Completed: the patient was informed about the CD4 test result or the CD4 test was done within a certain time period after the HIV test; *LTP: loss to programme

Meta-analyses

Six studies covering period from HIV diagnosis to ART start (stages 1 to 3)

Figure 2 summarizes the meta-analyses of the six studies that provided information on the period spanning HIV infection to start of ART. Of 100 patients who tested positive for HIV, 72 (95% CI 60–84) patients had a CD4 cell count measured, 40 (95% CI 26–55) were eligible for ART and 25 (95% CI 13–37) started ART.

Figure 2.

Percentage of HIV positive patients completing different stages between testing positive for HIV infection and start of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Results from meta-analysis of six studies covering the period from HIV testing to start of ART. The six studies include 58,746 patients (Bassett et al. 2010, Ingle et al. 2010, Kohler et al. 2011, Kranzer et al. 2010, Micek et al. 2009, Tayler-Smith et al. 2010).

Stage 1: From HIV to CD4 testing

CD4 cell count was measured in 77.6% (95% CI 71.0–84.2) of patients, with substantial between-study heterogeneity (I2=99.9%, P-value <0.0001). The median time from HIV testing to the first CD4 cell count was 56 days in Losina et al and 60 days in Micek et al. Loubiere et al reported that 56.8% of patients had their CD4 cell count measured within 30 days of the HIV test, and Larson et al (2010a) reported that CD4 cell counts were measured on the same day that the HIV test was administered. Kranzer et al was the only study assessing the different modes of entry into care during this stage: The median time was between 2 and 3 days, regardless of whether the patients entered via voluntary counselling and testing, via antenatal care or from a TB or sexually transmitted infections (STI) clinic.

Stage 2: Assessment of eligibility for ART

The median CD4 cell count at presentation to the clinic ranged from 154 (IQR 57–302) to 274 (IQR 139–435) cells/μl in the 6 studies where this information was provided (Table 1). The percentage of patients with a CD4 cell count who were eligible for ART was 56.5 % (95% CI 49.3–63.6), again with substantial between-study heterogeneity (I2=99.5%, P-value <0.0001).

Stage 3: From eligibility to start of ART

Eighteen studies reported the percentage of patients who started ART after becoming eligible: the overall estimate was 62.9% (95% CI 55.2–70.7); I2=99.7%, heterogeneity P-value <0.0001. In meta-regression the estimated percentage of patients starting ART increased from 44% to 81% as the percentage of women increased from 50% to 75% and no other factors were associated with the percentage of patients starting ART. Of note, two programmes in which very few eligible patients started ART (Murphy et al. 2010, Zachariah et al. 2006) included only patients who had entered the HIV programme from a TB clinic. 5 of the 25 studies reported on the median duration from becoming eligible to starting ART. The median duration was 22 days (McGrath et al. 2010), 34 days (Lawn et al. 2006), 83 days (Murphy et al. 2010), 95 days (Ingle et al. 2010) and 108 days (Bassett et al. 2009). Figure S2 shows the forest plots from the meta-analyses of all three stages.

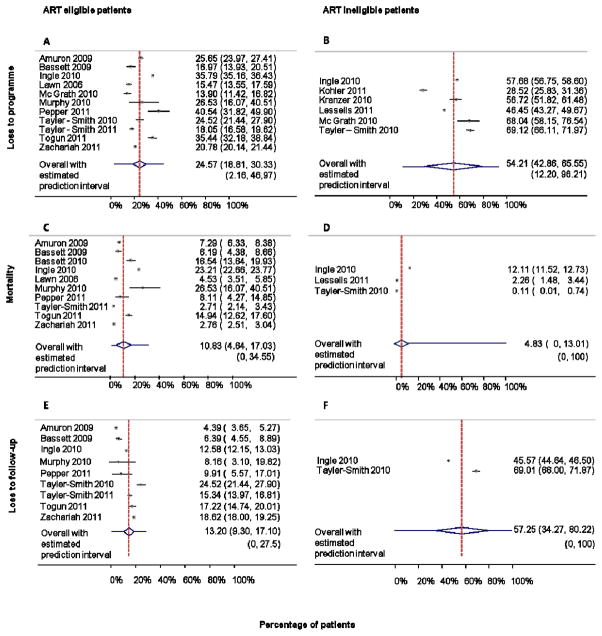

Pre-ART loss to programme, loss to follow-up, mortality and transfer-out

Figure 3 shows forest plots of overall loss to programme, loss to follow-up and mortality by ART eligibility. Among eligible patients 24.6% (95% CI 18.8–30.3) were lost to programme (Figure 3A) whereas among ineligible patients 54.2% (95% CI 42.8–72.0) were (Figure 3B). Mortality before treatment initiation in eligible patients was 10.8 % (95% CI 4.6–17.0; Figure 3C), with rates ranging from 1.6 to 53.2 per 100 person-years (Table 1). In 3 studies reporting on patients not yet eligible for ART, 4.8% (95% CI 0–13.0) died (Figure 3D). For loss to follow-up, the corresponding numbers were 13.2% (95% CI 9.3–17.1, Figure 3E) in eligible patients and 57.3% (95%CI 34.3–80.2, Figure 3F) in ineligible patients. Data on transfers out were reported in only few studies: overall 5.5% (95% CI 0–13.3%) of patients were transferred before ART initiation (2 studies). Transfers prior to ART initiation were more common in ART eligible patients: 20.1% (95% CI 7.6–32.6%), based on 4 studies.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of loss to programme, mortality and loss to follow-up during the pre-ART phase, according to whether patients were or were not eligible for ART. Panel A/B: Percentage of ART eligible/ineligible patients becoming loss to programme (LTP) before ART start. LTP includes mortality, loss to follow-up, transfer out and alive but not in programme. Panel C/D: Percentage of ART eligible/ineligible patients dying before ART start. Panel E/F: Percentage of ART eligible/ineligible patients becoming lost to follow-up before ART start.

Predictors of mortality, loss to programme, CD4 cell count determination and ART initiation

These results are summarized in Tables S1 and S2. Briefly, men were more likely to be lost to programme and less likely to start ART than women. The same association was described for patients with a lower socioeconomic status and lower CD4 count, and for later time periods. Conversely, older age and less advanced clinical stage were associated with start of ART. Only a few studies analysed predictors of mortality and of having a CD4 cell count determined.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis, based on more than 140,000 patients from 12 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, shows that pre-ART attrition is high: only about 25 of 100 newly diagnosed patients with HIV started ART even though in most clinics the median CD4 cell count at presentation was below 200 cells/μl. Loss to programme was twice as high in patients not yet eligible for ART as in patients eligible for ART, whereas mortality was more than twice as high in eligible patients compared to ineligible patients. The few studies that reported on predictors of loss to programme showed higher rates of loss in men, in patients with low CD4 cell counts, in patients of low socio-economic status, and in recent time periods.

Many patients with a positive HIV test were lost before eligibility for ART was determined. This is illustrated by Micek et al. (2009), most of whose patients had to be referred to the ART clinic for CD4 measurements: immune status was assessed in fewer than half of the patients. Two recently published studies suggested that point-of-care CD4 tests could improve the linkage to care. Faal et al (2011) found that providing the CD4 results at the time of HIV testing increased ART initiation rates, and in Mozambique Jani et al. (2011) showed that after the introduction of a point-of-care CD4 test, the proportion of patients lost to follow-up dropped from 57% to 21%. In some studies CD4 counts were measured more than two months after the HIV test and in only one site CD4 testing was done on the same day as the HIV test (Larson et al. 2010a). Unfortunately the latter study did not evaluate pre-ART loss to programme and it is unclear whether this approach led to a higher proportion of patients starting ART.

The design of some studies may explain why the proportion of patients with a CD4 cell count differed (Larson et al. 2010b, Kohler et al. 2011, Pepper et al. 2011). Larson et al distinguished between measured and completed CD4 cell count testing: 84.6% of the HIV positive patients had a CD4 cell count measured but only 53.1% of the eligible, and 45.7% of the not yet eligible patients picked up the results. Pepper et al included only HIV positive patients on TB treatment; in this integrated TB/HIV clinic the majority of patients had a pre-ART CD4 test done as part of the routine follow-up to determine eligibility for ART. In Kohler et al’s study in 2011, the introduction of free Cotrimoxazole (CTX) prophylaxis improved pre-ART retention and CTX provision may therefore be associated with a larger proportion of patients with a CD4 cell count. Different study locations, patient management strategies and local guidelines are other possible sources of heterogeneity. Predictors of receiving a CD4 cell count were also investigated in a recent study by a mobile HIV testing unit in South Africa. Low CD4 cell count, female sex, and the availability of a phone correlated with reception of test results. Patients with the lowest CD4 cell counts were most likely to be linked to facility-based HIV care (Govindasamy et al. 2011).

It is worrisome that few patients started ART despite low CD4 cell counts at presentation. Although ART eligibility criteria varied between studies, the majority used a CD4 threshold of 200 cells/μl. With the new threshold of 350 cells/μl or a universal ‘test and treat’ approach, the number of ART eligible patients will increase substantially. It is unclear what the significance of our results for a ‘test and treat’ strategy is. Although all HIV patients would qualify for ART, the high loss to follow-up rate among ineligible patients may also demonstrate how difficult it is to retain asymptomatic patients in care. Only few studies evaluated the factors associated with loss to follow-up and, interestingly, these factors were previously described as predictors of LTFU in patients on ART (Maskew et al. 2007, Ekouevi et al. 2010, Makombe et al. 2007, Boyles et al. 2011). The high LTFU rate in younger men may have psychosocial and structural origins (Cornell et al. 2009) while the increase over time may be due to an overburdened health system as the number of patients continues to increase.

This systematic review has several limitations. First, in all meta-analyses between-study heterogeneity was substantial. Second, differing definitions of loss to follow-up and ART eligibility criteria made comparing the studies difficult. Patients lost to follow-up may re-enter the health system later, when they are much sicker. Also, many studies did not describe the clinical and immunological criteria for ART eligibility in detail. Third, the number of included studies and countries was limited and only few studies covered the whole pre-ART period from HIV diagnosis to ART initiation; generalizability may therefore also be limited. Nor could we determine the point at which LTFU and mortality rates were highest. Fourth, only a few studies reported on the proportion of patients transferred out. In other studies these patients may have been assumed lost to follow-up, thus underestimating linkage to care. Fifth and finally, the reasons patients are lost to care are poorly reported and tracing these patients is rarely described. Mortality is generally expected to be underestimated because patients lost to follow-up are at higher risk of death (Brinkhof et al. 2009).

Our findings illustrate the urgent need to find ways to improve linkage between HIV testing and care in low-income countries. Possible interventions to maximize retention in care include (i) making point-of-care CD4 cell counts available at HIV testing facilities to minimize losses between HIV diagnosis, CD4 count and pick-up of the result; (ii) reduce the number of required visits before ART initiation and thus the financial burden on patients; (iii) keep the time period between ART eligibility and initiation as short as possible without undermining ART counselling, (iv) motivate ineligible patients to return in regular intervals and (v) introduce health information systems to better monitor the pre-ART period and patient movement and trace patients not returning to re-assess treatment eligibility.

In conclusion, this systematic review shows that linkage from HIV diagnosis to HIV care is poor in resource limited settings. In order to achieve satisfying ART coverage, monitoring of pre-ART patients needs to be improved and strategies to increase retention in care need to be implemented.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kali Tal for commenting and editing the manuscript and Julia Bohlius for helpful discussions. The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a PROSPER fellowship to OK funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and a PhD student fellowship to JE from the Swiss School of Public Health.

References

- Amuron B, Namara G, Birungi J, et al. Mortality and loss-to-follow-up during the pre-treatment period in an antiretroviral therapy programme under normal health service conditions in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:290. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Regan S, Chetty S, et al. Who starts antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa?… not everyone who should. AIDS. 2010;24:S37–S44. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000366081.91192.1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Wang B, Chetty S, et al. Loss to care and death before antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51:135–139. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a44ef2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyles TH, Wilkinson LS, Leisegang R, Maartens G. Factors influencing retention in care after starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural South african programme. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. The Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell M, Myer L, Kaplan R, Bekker LG, Wood R. The impact of gender and income on survival and retention in a South African antiretroviral therapy programme. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14:722–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekouevi DK, Balestre E, Ba-Gomis FO, et al. Low retention of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in 11 clinical centres in West Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010;15:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faal M, Naidoo N, Glencross DK, Venter WD, Osih R. Providing immediate CD4 count results at HIV testing improves ART initiation. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;58:e54–e59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182303921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairall LR, Bachmann MO, Louwagie GM, et al. Effectiveness of antiretroviral treatment in a South African program: a cohort study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:86–93. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng EH, Bwana MB, Kabakyenga J, et al. Diminishing availability of publicly funded slots for antiretroviral initiation among HIV-infected ART-eligible patients in Uganda. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks CF, Crowley S, Ekpini R, et al. The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. The Lancet. 2006;368:505–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy D, van Schaik N, Kranzer K, Wood R, Mathews C, Bekker LG. Linkage to HIV care from a mobile testing unit in South Africa by different CD4 count strata. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;58:344–352. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822e0c4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingle SM, May M, Uebel K, et al. Outcomes in patients waiting for antiretroviral treatment in the Free State Province, South Africa: prospective linkage study. AIDS. 2010;24:2717–2725. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833fb71f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani IV, Sitoe NE, Alfai ER, et al. Effect of point-of-care CD4 cell count tests on retention of patients and rates of antiretroviral therapy initiation in primary health clinics: an observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2011;378:1572–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R, Orrell C, Zwane E, Bekker LG, Wood R. Loss to follow-up and mortality among pregnant women referred to a community clinic for antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2008;22:1679–1681. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830ebcee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser O, Anastos K, Schechter M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings 1996 to 2006: patient characteristics, treatment regimens and monitoring in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008;13:870–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Martin JN, et al. Late-disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:280–289. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler PK, Chung MH, McGrath CJ, Benki-Nugent SF, Thiga JW, John-Stewart GC. Implementation of free cotrimoxazole prophylaxis improves clinic retention among antiretroviral therapy-ineligible clients in Kenya. AIDS. 2011;25:1657–1661. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834957fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P, et al. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, et al. Early loss to follow up after enrolment in pre-ART care at a large public clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010a;15:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, et al. Lost opportunities to complete CD4+ lymphocyte testing among patients who tested positive for HIV in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010b;88:675–680. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn SD, Myer L, Harling G, Orrell C, Bekker LG, Wood R. Determinants of mortality and nondeath losses from an antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa: implications for program evaluation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43:770–776. doi: 10.1086/507095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn SD, Myer L, Orrell C, Bekker LG, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing a community-based antiretroviral service in South Africa: implications for programme design. AIDS. 2005;19:2141–2148. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194802.89540.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Cooke GS, Newell ML. Retention in HIV Care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;56:e79–e86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182075ae2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losina E, Bassett IV, Giddy J, et al. The “ART” of linkage: pre-treatment loss to care after HIV diagnosis at two PEPFAR sites in Durban, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loubiere S, Boyer S, Protopopescu C, et al. Decentralization of HIV care in Cameroon: increased access to antiretroviral treatment and associated persistent barriers. Health Policy. 2009;92:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makombe SD, Jahn A, Tweya H, et al. A national survey of teachers on antiretroviral therapy in Malawi: access, retention in therapy and survival. PLoS One. 2007;2:e620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskew M, MacPhail P, Menezes C, Rubel D. Lost to follow up: contributing factors and challenges in South African patients on antiretroviral therapy. South African Medical Journal. 2007;97:853–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May M, Boulle A, Phiri S, et al. Prognosis of patients with HIV-1-infection starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a collaborative analysis of scale-up programmes. The Lancet. 2010;376:449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath N, Glynn JR, Saul J, et al. What happens to ART-eligible patients who do not start ART? Dropout between screening and ART initiation: a cohort study in Karonga, Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Munyenyembe T, Szumilin E, et al. Vital status of pre-ART and ART patients defaulting from care in rural Malawi. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010;15:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micek MA, Gimbel-Sherr K, Baptista AJ, et al. Loss to follow-up of adults in public HIV care systems in central Mozambique: identifying obstacles to treatment. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52:397–405. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab73e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulissa Z, Jerene D, Lindtjørn B. Patients present earlier and survival has improved, but pre-ART attrition is high in a six-year HIV cohort data from Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy RA, Sunpath H, Taha B, et al. Low uptake of antiretroviral therapy after admission with human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2010;14:903–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng-Ooko V, Ochieng D, Sidle JE, et al. Influence of gender on loss to follow-up in a large HIV treatment programme in western Kenya. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:681–688. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper DJ, Marais S, Wilkinson RJ, Bhaijee F, De Azevedo V, Meintjes G. Barriers to initiation of antiretrovirals during antituberculosis therapy in Africa. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8:e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott V, Zweigenthal V, Jennings K. Between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy: assessing the effectiveness of care for people living with HIV in the public primary care service in Cape Town, South Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2011;16:1384–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, et al. Demographic characteristics and opportunistic diseases associated with attrition during preparation for antiretroviral therapy in primary health centres in Kibera, Kenya. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2011;16:579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Massaquoi M, et al. Unacceptable attrition among WHO stages 1 and 2 patients in a hospital-based setting in rural Malawi: Can we retain such patients within the general health system? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;104:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togun T, Peterson I, Jaffar S, et al. Pre-treatment mortality and loss-to-follow-up in HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-1/HIV-2 dually infected patients eligible for antiretroviral therapy in The Gambia, West Africa. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2011;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Borght SF, Clevenbergh P, Rijckborst H, et al. Mortality and morbidity among HIV type-1-infected patients during the first 5 years of a multicountry HIV workplace programme in Africa. Antiviral Therapy. 2009;14:63–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisatio. [accessed 6 August 2012];HIV treatment reaching 6.6 million people, but majority still in neeed. 2011 News release June 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2011/hivtreatement_20110603/en/index.html.

- Zachariah R, Harries AD, Manzi M, et al. Acceptance of anti-retroviral therapy among patients infected with HIV and tuberculosis in rural Malawi is low and associated with cost of transport. PLoS One. 2006;1:e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah R, Tayler-Smith K, Manzi M, et al. Retention and attrition during the preparation phase and after start of antiretroviral treatment in Thyolo, Malawi, and Kibera, Kenya: implications for programmes? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;105:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.