Abstract

Genetic test results can have considerable importance for patients, their parents and more remote family members. Clinical therapy and surveillance, reproductive decisions and genetic diagnostics in family members, including prenatal diagnosis, are based on these results. The genetic test report should therefore provide a clear, concise, accurate, fully interpretative and authoritative answer to the clinical question. The need for harmonizing reporting practice of genetic tests has been recognised by the External Quality Assessment (EQA), providers and laboratories. The ESHG Genetic Services Quality Committee has produced reporting guidelines for the genetic disciplines (biochemical, cytogenetic and molecular genetic). These guidelines give assistance on report content, including the interpretation of results. Selected examples of genetic test reports for all three disciplines are provided in an annexe.

Diagnostic genetic testing is an extremely rapidly expanding area encompassing a broad range of laboratory investigations to analyse chromosomes (from classical karyotype to molecular cytogenetics), nucleic acids (DNA, RNA), proteins and metabolites used to detect heritable or somatic mutations, genotypes or phenotypes related to disease and health. Genetic testing requires particular consideration in that it is usually performed only once in a patient's lifetime, and the results may have considerable importance for lifetime decisions not only for the individuals being tested but also for children and family. Interpreting and reporting variation in germline chromosomes, DNA sequences or their products is a heavy clinical responsibility for prediction of susceptibility to disease, patient diagnosis, prognosis, counselling, treatment or family planning. Providing a set of reporting frameworks that can be customised for different testing contexts but share some common principles could be beneficial to the practice of a number of laboratories, including non-OECD members and/or laboratories that do not participate in External Quality Assessments (EQA), and to laboratories with blurred boundaries between research and genetic testing services.

Although several guidelines already exist for reporting the results of genetic testing,1,2,3 these focus on molecular genetic testing and do not cover the other two branches of laboratory genetics, namely biochemical genetics and cytogenetics. Based on recent surveys of EQA results presented by some European EQA providers and the request from genetic laboratories for comprehensive reporting guidelines, it was considered that a unifying attempt to harmonise the reporting practice of genetic tests in Europe and neighbouring countries would be welcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

On behalf of the Genetic Services Quality Committee of the European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG, https://www.eshg.org/), a workgroup composed of experts with long-term knowledge and experience in genetic testing was invited to several meetings, with the objective to answer the key question: is it feasible to clarify a minimum set of issues and frameworks in reporting that would fit different testing scenarios encountered in cytogenetic, molecular and biochemical genetic laboratories? This workgroup included academic experts in clinical cytogenetics, molecular genetics, biochemical genetics, clinical genetics, bioinformatics, patient groups, accreditation bodies and EU organisations of EQA (proficiency testing) for genetic diagnostic laboratories. A preliminary draft including major key issues in reporting was discussed through meetings, then reviewed and updated by each of the participants, until reaching a consensus on shape and contents of these guidelines and recommendations.

Although these guidelines do not specifically address the reporting of results generated by massively parallel DNA sequencing, the reporting of the pathogenic variants identified by this method (or their absence) does not differ from reporting such variants found by conventional DNA sequencing.

General comments

Scope of the document

These recommendations aim to provide guidance for reporting results of genetic testing by biochemical genetic, cytogenetic and molecular genetic techniques. They are distinct from (and bring additional information on reporting to) recently published documents such as good laboratory practices regulations,4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 quality assurance frameworks delivered by EuroGentest (www.eurogentest.org), evaluation frameworks and assessment of analytic validity developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ11), CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) recommendations for good laboratory practices in molecular genetic testing12 or guidelines for licensing, certification or accreditation processes and general guidelines for quality assurance in molecular genetic testing provided by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).1 Reporting targeted genetic testing for monogenic disorders and for susceptibility traits with proven clinical utility, regardless of the extent of testing (that is, single gene or multiple genes) is within the scope of these recommendations.

Definition

Reports are specific formal medical documents from the laboratory to the referring physician and/or other health-care professionals regarding the results and interpretation of genetic testing in a patient and/or members of a family. The main goal of reports is to provide a clear, concise, accurate, fully interpretative and authoritative answer to a clinical question.

Minimal set of clinical information accompanying the samples

For the correct interpretation of genetic tests, a minimal set of clinical information from the referring physician or genetic counsellor must accompany the sample. The purpose of testing must be clearly identified (for example, confirmation of diagnosis that was established by other means, differential diagnosis of several disorders, carrier testing, presymptomatic testing and prenatal testing). The ethnicity of the individual tested should be included if relevant for the purpose of testing; this information may be useful to select the most appropriate test methods and to calculate residual risks. The referring physician should provide all clinical, laboratory, imaging, genealogic, genetic or other data that are relevant to the purpose of testing, and that may guide the laboratory in selecting the optimal laboratory procedures. For biochemical genetic testing, the referral should also include information on the conditions under which the samples were collected, on fed/fasting status and on the use of medications. For some clinical situations, it is essential to provide the laboratory with a family tree constructed by a genetic professional. For index cases, laboratories are strongly encouraged to request a more detailed disease-specific clinical form completed by the referring physician or genetic counsellor. Owing to potential deleterious consequences of shortcomings in the communication of critical information pertinent for the interpretation of results and clinical decision-making, some laboratories provide the ordering clinician with a clinical requisition form specific for the disease, which must be filled, signed and joined to the sample. Another benefit is to avoid non-medical office staff ordering genetic tests.13 If the purpose of testing or relevant clinical information is not provided, laboratories should request the missing clinical information required to perform the agreed testing.

Results of how many individuals in one report?

It is recommended that each unrelated patient should be reported in a separate and unique document, as many reports may ultimately be filed in individual patient or family files (for reasons of confidentiality). However, in recessive disorders it is appropriate (where legally permitted) to report the couple's risk of having affected children together, which requires that both individuals are clearly identified.

When several family members are analysed simultaneously, policies vary as to whether they should be reported on the same or on different reports. This will depend on the disorder and the nature of the referral reason, as well as on the legislation on genetic testing in the respective country.

Guidelines for reporting

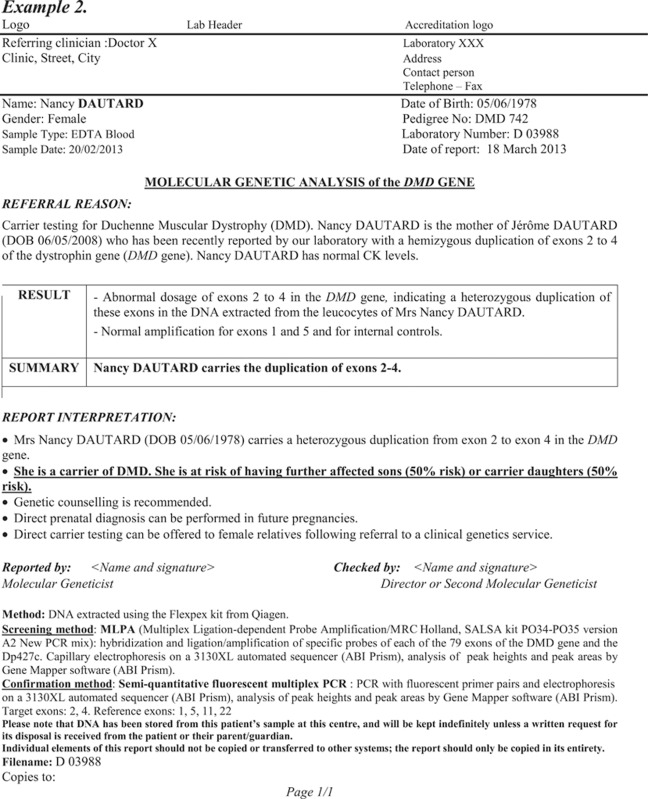

General guidelines and examples of reports are available in the Annex to these guidelines and on the ESHG, EuroGentest, CEQA (Cytogenetic European Quality Assessment), CF Network and ERNDIM (European Research Network for evaluation and improvement of screening, Diagnosis and treatment of Inherited disorders of Metabolism) websites for consultation.

Contents of the report

The following elements should be present in every report:

Administrative

Title (for example, ‘Result of molecular genetic analysis of the XX gene' or ‘Results of enzyme assay for XX disease(s)' or 'Results of constitutional microarray analysis').

The identity of the laboratory performing the analysis and issuing the report, with full contact details. If parts of analyses have been carried out in other laboratories, this fact must be clearly and unequivocally stated.

Full date of the report.

Page numbers indicating the total number of pages, essential when multiple pages are used. (for example, 1/1 or page 1 of 2).

Name and full address of the physician referring the patient.

Signature. The report must be electronically or manually signed by the authorised laboratory specialist who validated the analysis and interpreted the result; co-validation and co-signature by a second competent person is recommended (and mandatory in some countries). The name and function of signatories must be given.

Patient and sample identification

Patient identification:

Full given name(s) and the surname (must be separate to avoid uncertainties, especially in sending samples to other countries).

Unequivocal date of birth.

Gender.

Fetal samples (CVS, amniocytes and so on) must be clearly distinguished from those of their mothers.

Note: Where legislation (for example, data protection legislation) prohibits the transmission of identifiable personal information, a code may be used instead of the patient's name.

Ethnic/geographic origin, if relevant.

Date (and time of sample collection, if available; this information is crucial for biochemical genetic testing).

Date (and time) of sample arrival to the laboratory.

Information on the status of the sample if relevant (for example, frozen, decomposed, haemolyzed).

Material that has been tested (for example, ‘EDTA blood', ‘cultured amniocytes', ‘DNA extracted from…', ‘heparin plasma', ‘urine' and so on). When the sample has been processed in another laboratory (for example, DNA has been extracted, plasma has been separated and frozen, amniocytes have been cultivated and so on) indicate precisely what was done with the samples and by whom (for example, sample: ‘DNA, extracted by XXXX, from blood').

Unique sample ID number for each sample tested.

Patient identifiers should be included on each page of a multipage report.

Restatement of the clinical question

The interpretation of genetic test results depends usually on the clinical context. Therefore, in the section GENERAL COMMENTS above, a minimal set of clinical and laboratory data requested from the referring physician or genetic counsellor has been defined. Based on this information provided by the attending physician or genetic counsellor, the reports of genetic testing should explicitly restate the clinical question being asked. This usually comprises at least the following three elements:

The disease(s) or marker(s) being requested for analysis (for example, cystic fibrosis, lysosomal storage disorders, inborn errors of metabolism, chromosomal abnormalities);

The type of required testing (for example, diagnostic confirmation, carrier status, prenatal diagnosis);

The referral reason—why the request is being made (for example, positive family history, multiple congenital abnormalities, fasting hypoglycaemia and so on).

When the referral is due to abnormal results of previous genetic testing in either the same laboratory or a different laboratory, this fact must be clearly indicated in the report, with a reference to the relevant previous report.

Specification of genetic tests used

Gives useful, brief information on the methods used in the analysis. Additional information may be in footnotes.

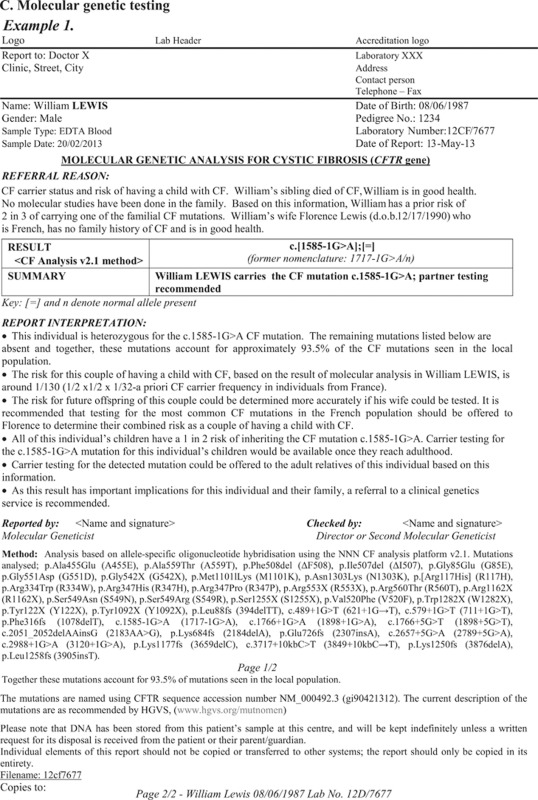

Gives full details of the extent of the tests (for example, which exons screened for deletions in DMD, which FISH probes used, which mutations looked for in CF, resolution of cytogenetic analyses and so on). This information is particularly important when reporting normal/no abnormality detected results.

Where a commercially available kit is used, this should be clearly identified in the report, including the reference and version of the kit (and, where applicable, the list of mutations included in the version used).

For molecular genetic testing, gives the gene reference sequence that has been used to identify and describe the variants.

Where appropriate, gives the detection rate (sensitivity) in the population of origin of the individual tested.

Results

Present the results in a brief and unambiguous form. If several different tests have been performed, the results should be shown separately for each of the tests. The terms ‘positive' and ‘negative' can be ambiguous and should not be used.

For molecular genetic testing, reference sequence (including Build No.) and nomenclature of detected genetic variants should be meaningful, unambiguous and consistent using the recommended HGVS nomenclature valid at the time of reporting. As both HGVS nomenclature and the reference sequences change in time, other descriptions of the variant that have been widely used in the past may be given in parentheses, if appropriate.

If more than one possibly pathogenic variant has been detected, a comment on the phase of variants (which may be unknown) should be added, taking into account the expected mode of inheritance of the disorder.

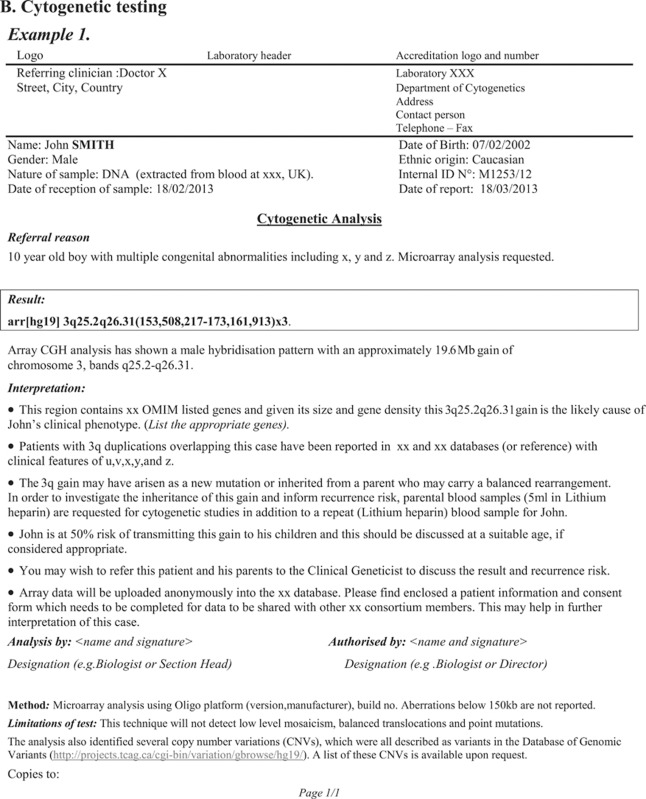

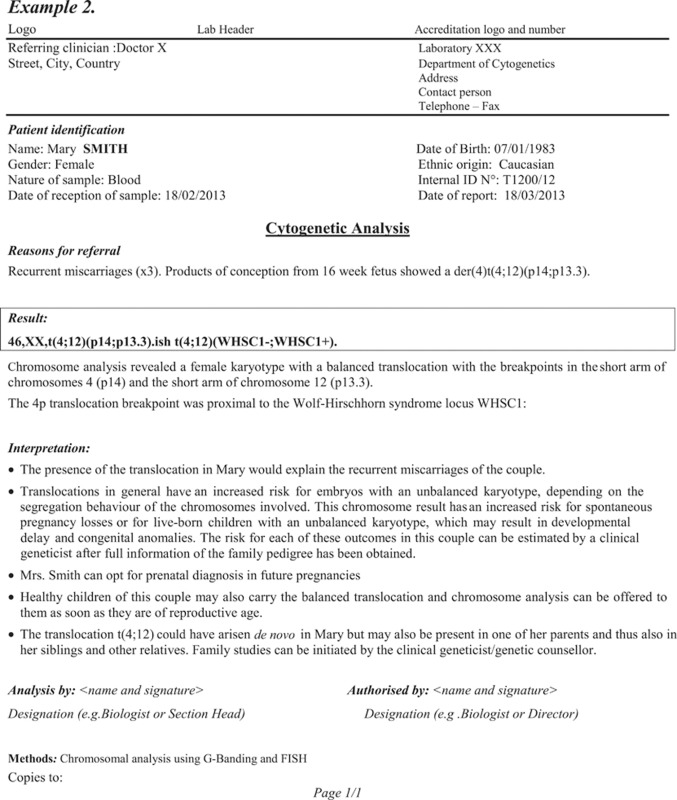

For cytogenetic and microarray testing, the most recent International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN) nomenclature should be used.

It may be useful to give a list of genes involved (by HGNC symbol and/or OMIM number) for abnormal microarray results and for other tests involving multiple genes.

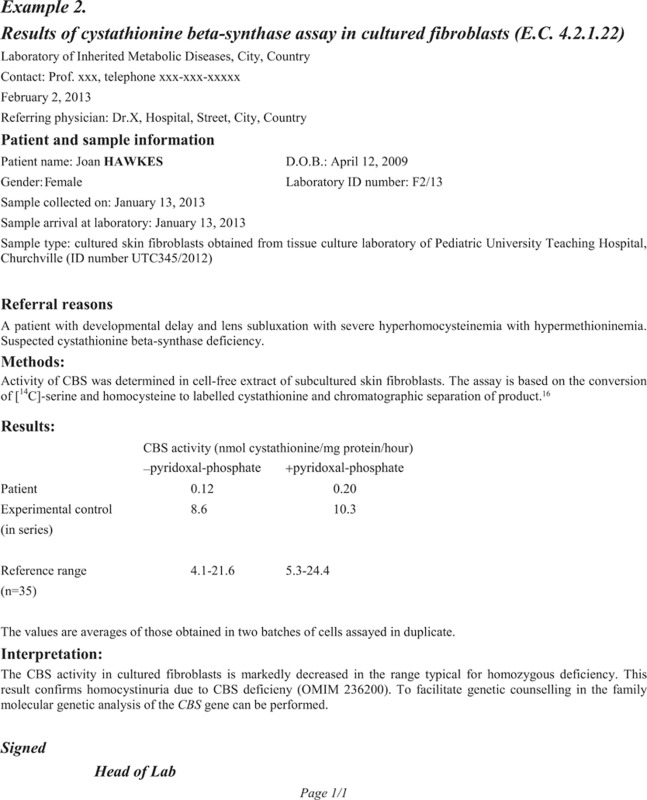

For biochemical genetic testing using qualitative tests, the report should clearly distinguish normal results from nonspecific findings and from clearly abnormal results (including an indication of which diseases are most likely). For quantitative analyses of single analytes, both the value and the reference range should be given. For enzyme assays it is usual to show, in addition, the activities of controls run in parallel with the patient sample; reports on enzyme activity should contain the E.C. number of the enzyme. For quantitative profile analyses, the report should only summarise the major findings distinguishing normal, nonspecific and disease-specific profiles; numeric values of the profile analyses should be sent as attachments.

Interpretation of results

General recommendations for the interpretation of genetic laboratory results are given in this section. The Quality Committee realises that differences between countries may exist, as to where the boundary of the responsibilities of laboratory specialist versus the clinician lies. For example, the use of prediction programs to predict the effect of a novel missense variant or a variant that may affect splicing is evidently the expertise and responsibility of the laboratory specialist. The same holds true for the interpretation of intermediate biochemical results, although the clinical phenotype may sometimes be decisive for the interpretation. On the other hand, relating the phenotype to what is known in literature on the effect of a rare copy number variant will highly depend on the background of the laboratory specialist (in some countries, cytogeneticists are clinical geneticists) and the referring clinician. With the use of new high-resolution- and high-throughput sequencing techniques, the number of (copy number) variants of unknown clinical significance will increase, and the prediction programs and the databases with normal variants have their limitations. Thus, laboratory and clinical specialists should discuss and document what the minimal interpretation in the laboratory report should be. In the opinion of the Quality Committee, the report should at least contain all relevant information that enables the clinician to perform the clinical interpretation using literature resources (for example, which RefSeq genes are located in a copy number loss, or what the results are of prediction programs on a missense variant and whether or not it has been reported in databases like dbSNP). It may be worthwhile to inform the clinician that genealogical/family studies may be helpful in the interpretation, and that the interpretation is based on current knowledge and thus may change in the future due to additional evidence.

Although this is beyond the scope of these recommendations for reporting results of diagnostic testing, the committee acknowledges the need for curated locus/disease-specific databases and databases of copy number variants. Such databases should be supported by an (international) expert committee (as proposed by Tavtigian et al.14).

The report must provide a full and clear interpretation of results, depending both on the clinical context and the reason for referral (for example, diagnostic test, carrier test, prenatal test). Reports on patients may be read by a variety of professionals involved in their care, many of whom will be unable to interpret fully the results of genetic testing. In order to provide a full interpretation, the results must be viewed in the context of the relevant clinical and family information available (for example, relationship between the patient and the index case where relevant, family pedigree, ethnic background, clinical and laboratory data provided by the referring physician and others).

If more tests have been carried out using the same sample(s), the interpretation part of the report should integrate the individual results and should answer the clinical question in a clear and concise way. This integration of findings with relevance to the tested individual is especially important when multiple susceptibility genetic variants have been analysed.

Answer the question in a concise and clear way, after taking into account any appropriate additional information supplied. It is recommended that laboratories highlight this conclusion (bold, underline, large font, text in a box and so on). In particular, remember that negative results (‘no mutation detected') can easily be misinterpreted by non-specialists as ‘exclusions'. Significance of results in respect to the referral reason (clinical question) should be clearly stated and should belong to one the following five categories. In some cases there may be more than one conclusion:

Normal finding(s) (physiological finding, normal variation): findings within the range of physiological variation for the given individual considering ethnicity, age, sex, maturity and other relevant factors; for example, nucleic acid sequence corresponding to the reference sequence or containing genetic variants considered usual variations at the time of reporting, chromosomal heteromorphisms as defined in the ISCN, frequently occurring CNVs reported in the database for genomic variants (DGV), concentrations of analytes in quantitative biochemical genetic tests within reference ranges, results of qualitative biochemical genetic tests showing a usual result/profile. If relevant, it may be important to provide an estimate of the diagnostic sensitivity (that is, the proportion of affected individuals likely to be detected; or one minus the false-negative rate). It can be useful to provide a key reference to support sensitivity estimates, when appropriate, but the report should not become a scientific discussion.

Non-specific finding(s) without clinical relevance: findings outside of the physiological variation but not associated with a known disease; (for example, elevation of multiple serum amino acids in a patient receiving parenteral nutrition, presence of drugs and their metabolites in biochemical tests, signs of sample decomposition). Such findings should only be reported if they may be relevant to the result (for example, issues of sample quality).

Incidental finding(s) with possible clinical relevance: findings indicating a clinically relevant issue, but unrelated to the clinical question that was asked (for example, signs of sex chromosome abnormality when analysing an X-linked disorder, evidence of predisposition to an unrelated condition). The decision on whether to report such findings will depend on local policy and on how the patient has been counselled about this possibility. A clear policy on reporting incidental findings should be in place in all institutions offering genetic testing.

Finding(s) of uncertain significance: findings outside of the physiological variation but with possible or putative relevance to the clinical question asked; for example, novel missense variants, novel putative splicing variants with unproven effect at RNA level, mosaicism or novel rearrangements in cytogenetic analyses, copy number variations and intermediate analyte concentration/enzyme activity, suggesting either heterozygosity or a mild phenotype. It is important that findings of uncertain significance are included in reports, as their significance may become clear at a later date. Attempts should be made to explain significance of the finding using literature, additional databases, prediction programs and other means, and to report the likelihood of the finding in respect to the clinical question asked. In some cases, it may be important to provide an estimate of diagnostic specificity, which indicates the risk of a false-positive result (for example, in late-onset diseases or in cases of reduced penetrance). When practical and appropriate, the advice of a Clinical Geneticist should be sought.

Pathognomonic (disease-specific, pathological) finding(s): findings that are outside of the physiological variation and that are, at the present state of knowledge, unequivocally associated with a clinically relevant disease or group of diseases. Pathogenicity of findings should be clearly supported from data in literature/databases, segregation analysis, functional tests of genetic variants and other relevant means.

Description of genotype can include the correct assignment of phase, which may require the study of familial segregation of alleles. When appropriate, reports must explicitly mention that ‘both parents should be tested to confirm their carrier status and to provide formal confirmation of the diagnosis of their child.'

When appropriate or required by the requesting physician, genetic carrier risks should be stated. Risk estimates may require the application of Bayesian calculations.

It should be indicated if further tests could be undertaken to improve the accuracy or scope of the interpretation. This may include tests for additional disorders or additional tests to more fully investigate the disease in question. If the additional tests suggested are not performed ‘in-house', alternative specialist laboratories where the sample may be sent may be proposed.

If any other information could be supplied or obtained by the referring clinician that might improve the accuracy of your interpretation, it should be stated in the report (for example, arranging testing of the index case in a family to confirm a diagnosis or to determine which mutations are present).

References: It may be useful to quote appropriate references for the interpretation of results, particularly of rare pathogenic and unclassified variants, as well as for certain risk calculations.

Requirement for genetic counselling: The report should carry the reminder to the referring physician that ‘genetic tests should be accompanied by genetic counselling' (or similar). In certain cases (prenatal diagnosis, presymptomatic testing or results with major implications for other family members), it is appropriate to indicate that ‘this result and its implications should be transmitted only in a specialized genetic consultation' (or similar).

Family follow-up: When a new diagnosis is made (positive result in a diagnostic confirmation), it is appropriate to state specifically that the result has ‘potentially important implications for other family members' or equivalent. Depending on the context, it may be appropriate to explicitly mention the recommendation to test the partner, the possibility of cascade screening tests in relatives, the possibility of prenatal diagnosis or preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Where appropriate, the risk for future offspring should be calculated and provided (using carrier frequencies from an appropriate population).

It should never be stated that prenatal or presymptomatic diagnosis is ‘indicated' or ‘necessary'. The role of the laboratory does not go beyond stating that prenatal/presymptomatic diagnosis would be possible.

Interim reports

It may in some circumstances be useful to issue a report before all studies are complete (for example, when indicative preliminary results have been obtained, but a long delay is expected before the final results will be ready). Interim reports should be clearly marked as such and should be worded to avoid misinterpretation of their status. Thus, phrases or summary statements appearing to give a definitive result should not be used. It should be clearly stated which analyses are still underway.

The definitive report should clearly state which are the new results, and should include a general conclusion, taking account of all results.

Reporting multiple patients

As a general rule, each unrelated patient should be reported on a separate and unique document, as the reports will ultimately be filed in individual patient or family files (as well as for reasons of confidentiality).

When several family members are analysed simultaneously, policies vary as to whether they should be reported on the same or on different reports. This will depend on the disorder, on the nature of the analysis and also on the legislation (in some countries, familial analysis and prenatal diagnosis for hereditary disorders can be referred only by clinical geneticists, and family files are stored only in genetic centres, and only relevant information is delivered to each individual).

Predictive test results must always be reported as separate, individual reports.

Linked-marker studies are only useful in the context of alleles inherited by several family members, which must be included in the report. It is recommended that the number of individuals reported should be limited to only those essential for accurate analysis. An interpretation and final risk should be given for only one person per report.

For prenatal diagnosis, it is recommended that the report includes only the result of the fetus. Parental results should be cross-referenced, but their results reported separately.

In carrier testing for a recessive disorder for a couple, the test results for one partner must be interpreted in light of the other partner's results. Laboratories may issue a single report, or separate reports with cross references to the partner's results (as the couple may separate). It is recognised that, in some jurisdictions, it is not permissible to mention more than one individual in a clinical report.

Where the result of the parents is needed to interpret the result in the child, only the array result of the specific CNV(s) in the parents is given in the child's report, and not the full array results.

Disclaimer

Disclaimers should only be included where they are relevant and useful; inclusion of multiple disclaimers on every report whether relevant or not is discouraged.

Where relevant, mention the possibility of errors due to factors beyond the control of the laboratory (for example, the risk of ‘non-paternity' and the need for family relationships as stated on the referral forms being correct; limited validity of biochemical testing if pre-analytical conditions were not well controlled).

In indirect (linkage) analyses, it is sometimes advisable to state that the ‘accuracy of the result depends on the clinical diagnosis and the assumption that gene X is responsible for the disease' (or similar).

Laboratories might wish to add a note of caution when reports are based on DNA samples or reports sent from another laboratory.

It may be advisable to add a standard phrase, indicating that ‘this report may not be copied or reproduced, except in its totality'.

Appendix

References

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Molecular Genetic Testing2007. Available at http://www.oecd.org/sti/biotech/oecdguidelinesforqualityassurancein genetictesting.htm .

- Best practice guidelines on reporting in molecular genetic diagnostic laboratories in Switzerland http://www.sgmg.ch/user_files/images/SGMG_Reporting_Guidelines.pdf .

- Clinical Molecular Genetics Society Best Practice Guidelines for Reporting Molecular Genetics results http://www.cmgs.org/BPGs/Reporting%20guidelines%20Sept%202011%20APPROVED.pdf .

- ACC Professional Guidelines for Clinical Cytogenetics General Best Practice v1.042007. Available at http://www.cytogenetics.org.uk/prof_standards/acc_general_bp_mar2007 _1.04.pdf .

- Berwouts S, Morris M, Dequeker E. Approaches to quality management and accreditation in a genetic testing laboratory. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:S1–S19. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham J.Quality control annd quality assurance in the biochemical genetic laboratoryIn: Blau N, Duran M, Gibson KM eds.: Laboratory Guide to the Methods in Biochemical Genetics Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg; 20087–22. [Google Scholar]

- European General Cytogenetic Guidelines and Quality Assurance2012 , http://e-c-a.eu/files/downloads/E.C.A._General_Guidelines_Version%202.0.pdf .

- Fowler B, Burlina A, Kozich V, Vianey-Saban C. Quality of analytical performance in inherited metabolic disorders: the role of ERNDIM. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:680–689. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-1025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RJ, Maher EJ, Quellhorst-Pawley B, Howell RT. An internet-based external quality assessment in cytogenetics that audits a laboratory's analytical and interpretative performance. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specific Constitutional Cytogenetic Guidelines2012 , http://www.e-c-a.eu/files/downloads/Specific_Constitutional_Guidelines_ NL30.pdf .

- Sun F, Bruening W, Erinoff E, Schoelles KM. Evaluation Frameworks and Assessment of Analytic Validity (Internet) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA; 2011. Addressing challenges in Genetic Test Evaluation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Gagnon M, Shahangian S, Anderson NL, Howerton DA, Boone DJ. Good laboratories practices for molecular genetic testing for heritable diseases and conditions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:RR-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin IM, Caggana M, Constantin C, et al. Ordering molecular genetic tests and reporting results. J Mol Diag. 2008;10:459–468. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavtigian S, Greenblatt MS, Goldgar DE, Boffetta P. Assessing pathogenicity: overview of results from the IARC unclassified genetic variants working group. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1261–1264. doi: 10.1002/humu.20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo P.Organic AcidsIn: Blau N, Duran M, Gibson KM (eds). Laboratory Guide to the Methods in Biochemical Genetics Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg; 2008137–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus JP. Cystathionine beta-synthase (human) Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:388–394. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]