Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is there an association between acute prenatal famine exposure or birthweight and subsequent reproductive performance and age at menopause?

SUMMARY ANSWER

No association was found between intrauterine famine exposure and reproductive performance, but survival analysis showed that women exposed in utero were 24% more likely to experience menopause at any age.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Associations between prenatal famine and subsequent reproductive performance have been examined previously with inconsistent results. Evidence for the effects of famine exposure on age at natural menopause is limited to one study of post-natal exposure.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

This cohort study included men and women born around the time of the Dutch famine of 1944–1945. The study participants (n = 1070) underwent standardized interviews on reproductive parameters at a mean age of 59 years.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

The participants were grouped as men and women with prenatal famine exposure (n = 407), their same-sex siblings (family controls, n = 319) or other men and women born before or after the famine period (time controls, n = 344). Associations of famine exposure with reproductive performance and menopause were analysed using logistic regression and survival analysis with competing risk, after controlling for family clustering.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Gestational famine exposure was not associated with nulliparity, age at birth of first child, difficulties conceiving or pregnancy outcome (all P> 0.05) in men or women. At any given age, women were more likely to experience menopause after gestational exposure to famine (hazard ratio 1.24; 95% CI 1.03, 1.51). The association was not attenuated with an additional control for a woman's birthweight. In this study, there was no association between birthweight and age at menopause after adjustment for gestational famine exposure.

LIMITATIONS, REASON FOR CAUTION

Age at menopause was self-reported and assessed retrospectively. The study power to examine associations with specific gestational periods of famine exposure and reproductive function was limited.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Our findings support previous results that prenatal famine exposure is not related to reproductive performance in adult life. However, natural menopause occurs earlier after prenatal famine exposure, suggesting that early life events can affect organ function even at the ovarian level.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This study was funded by the NHLBI/NIH (R01 HL-067914).

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

Not applicable.

Keywords: prenatal famine exposure, maternal undernutrition, birthweight, reproductive performance, age at menopause

Introduction

Female reproductive ageing represents the decline, with increasing age, in both quantity and quality of the ovarian follicle pool (te Velde and Pearson, 2002). Demographic studies have shown that women experience optimal fertility before the age of 30–31 years (Spira, 1988; Wood, 1989). Thereafter, a gradual decline in monthly fecundity rate is observed, with an acceleration from 36 years onwards. The age-related decrease in follicle numbers dictates the onset of cycle irregularity and menopause, the final cessation of menses, which marks the end of female reproductive function (Broekmans et al., 2009). In general, women experience no signs of this reproductive ageing process, except for the occurrence of subfertility and involuntary childlessness.

Several factors contributing to the rate of the reproductive ageing process have been identified. Smoking and nulliparity have been associated with an early age at menopause (Gold et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2012); other identified predictors are lower socioeconomic status, early menarche and a low body mass index (Harlow and Signorello, 2000; Gold et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2012). Next to environmental and life-style factors, multiple genetic factors have been claimed to influence menopausal timing (Voorhuis et al., 2010; Stolk et al., 2012). However, the variation in age at menopause can only partly be explained by these characteristics.

An adverse environment in utero is thought to permanently change the physiology, metabolism and organ structure of the developing fetus and thereby affect health in later life (Barker, 1995). As a complex interplay of hormonal and physical events is necessary for normal reproductive function, it has been hypothesized that caloric restriction during pregnancy might also affect in utero development of the organs responsible for reproductive function, and as such, may affect fertility and age at menopause (Lumey and Stein, 1997).

Growth-retarded fetuses have impairment of ovarian development, which may also have implications for the timing of menopause (de Bruin et al., 1998). Furthermore, low birthweight infants with prematurity or growth retardation tend to have fewer offspring (Swamy et al., 2008; de Keyser et al., 2012), and a decreased age at menopause has been reported following exposure to famine in early childhood (Elias et al., 2003).

Two previous studies of prenatal famine exposure and subsequent reproductive performance have been reported, with inconsistent results. Lumey and Stein, (1997) found no adverse impact of famine exposure on a range of measures of female fertility ascertained at age 43 years, while Painter et al. (2008), who interviewed the same sample of exposed women at a mean age of 50 years, but used a different sample of controls, found a small but significant decrease in the prevalence of nulliparity.

We therefore conducted a study in an independent sample, at an age when the study population would have been expected to be post-menopausal. The aim of the present study was to assess the effect of gestational exposure to famine on measures of reproductive function in both men and women. We also examined whether there is a relation between famine exposure, birthweight and age at menopause.

Materials and Methods

Historical background: the Dutch Hunger Winter

The Dutch famine, during the winter of 1944–1945, provides a unique opportunity to study the effects of maternal undernutrition at different stages of gestation on adult health. The famine resulted from a transport embargo on food enforced by the German military initiatives and was clearly defined in place (limited to the western Netherlands) and time (October 1944–May 1945). Widespread starvation was seen in the western Netherlands and the severity of the famine has been fully documented (Burger et al., 1948; Stein et al., 1975; Lumey and Van Poppel, 1994). Official rations, which were generally adequate before the onset of famine (Trienekens, 2000), fell <900 kcal/day by 26 November 1944 and consisted mainly of bread and potatoes, then eventually decreased to 500 kcal/day by April 1945. The famine ceased immediately at liberation in May 1945, after which Allied food supplies were rapidly restored and distributed across the country. Widespread effects of the famine regarding mortality, especially in the youngest and oldest age categories, fertility, pregnancy weight gain and infant size at birth have been documented (Sindram, 1953; Stein and Susser, 1975a,b; Lumey and Van Poppel, 1994; Stein et al., 1995; Stein et al., 2004).

Study population

As described in greater detail elsewhere (Lumey et al., 2007), a birth cohort of 3307 live born singleton births was identified through three institutions in the western Netherlands which experienced famine (the midwifery training schools in Amsterdam and Rotterdam and the university hospital in Leiden). We selected all 2417 infants born between 1 February 1945 and 31 March 1946, whose mothers experienced exposure to famine during or immediately preceding that pregnancy. Moreover, we selected a sample of 890 infants, born from 1943 to 1947, whose mothers did not experience any famine exposure during this pregnancy and whom we designated as hospital time controls. The sample of time controls consisted of an equal number of births for each month and was allocated across the three institutions according to their size.

Tracing to current address

To trace the 3307 infants to their current address, we filed a request to the Population Register in the municipality of birth, providing the names and addresses at birth. The Population Register in Rotterdam declined to trace 130 (4%) individuals born out of wedlock, while 308 (9%) were reported to have died in the Netherlands, 275 (8%) were reported to have emigrated, and a current address could not be located for 294 subjects (9%). As a result, address information was obtained for 2300 individuals (70% of the birth cohort).

Enrolments and examinations

These 2300 individuals were sent a letter of invitation signed by the current director of the institution in which they were born, enclosed with a brochure describing the study and a response card. One reminder letter was sent to all non-responders. Subsequently, all individuals with a same-sex sibling were asked to contact this sibling for study enrolment. For the siblings, there was no information available from prenatal or delivery records, as they were not members of the birth series in the three institutions and were generally delivered elsewhere. Initially, our study design aimed at recruiting same-sex sibling pairs only and the lack of an available sibling was a reason for ineligibility. Later, all individuals from the birth series were contacted once more and invited for the study irrespective of sibling availability.

We completed 1070 telephone interviews. All study protocols were approved by the Human Subjects (Medical ethics) committees of the participating institutions. All participants provided verbal consent at the start of the telephone interview.

Famine exposure during gestation

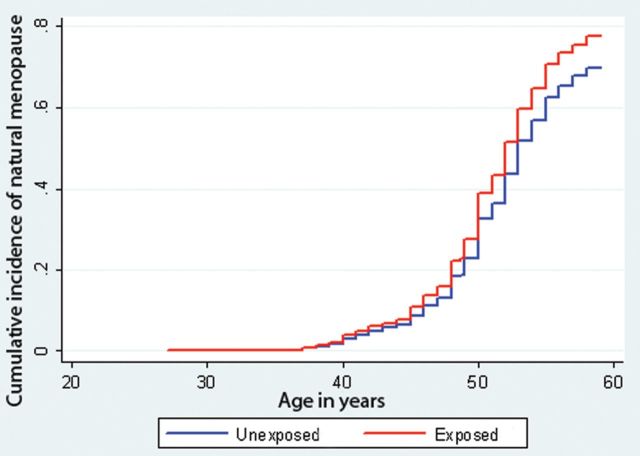

The start of gestation was defined by the date of last menstrual period (LMP) as noted in the hospital records unless it was missing or implausible (12%). In case the LMP was missing, we derived the date from relevant annotations on the birth record and estimated gestational age from birthweight and date of birth, using cutoffs from tables of sex-, parity- and birthweight-specific gestational ages from the combined birth records of the Amsterdam midwifery school (1948–1957) and the University of Amsterdam Obstetrics Department (1931–1965) (Lumey et al., 2009). Subsequently, the most consistent and plausible estimation of gestational age was selected for each infant and used together with date of birth to derive the date of LMP. Gestational famine exposure was characterized by determining the gestational weeks during which the mother was exposed to an official ration of <900 kcal/day between 26 November 1944 and 12 May 1945. We considered the mother as exposed to famine in gestational weeks of 1–10, 11–20, 21–30 or 31 to delivery if these gestational time windows were entirely included in this period. By this means, all pregnancies with a LMP date between 26 November 1944 and 4 March 1945 were considered exposed in Weeks 1–10, those with an LMP between 18 September 1944 and 24 December 1944 were exposed in Weeks 11–20, those with an LMP between 10 July 1944 and 15 October 1944 were exposed in Weeks 21–30 and those with an LMP between 2 May 1944 and 24 August 1944 were exposed in Week 31 through to delivery. These definitions mean that any woman could have been exposed to famine during, at most, two adjacent 10-week periods. We characterized any prenatal famine exposure if infants were exposed in more than one of the 10-week periods. In Fig. 1, the resulting sample size in the males and females by (overlapping) periods of exposure for gestational weeks 1–10, 11–20, 21–30 and 31 to delivery are depicted.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population. Exposed any week: all births between 1 February 1945 and 31 March 1946 and divided in gestational weeks of exposure to an official ration of <900 kcal/day. Time controls: births from 1943 to 1947. Sibling controls: same sex siblings unexposed to famine.

Study parameters

The main measures to express reproductive performance included (i) never given birth or fathered a child (nulliparity) and (ii) attempting to conceive for at least 12 months without success (infertility). Natural menopause was defined as cessation of menstrual periods for 12 consecutive months in the absence of any other known cause of amenorrhea and this criterion was used to classify women as premenopausal or post-menopausal. Women were further categorized as having undergone induced menopause (by ovariectomy, hysterectomy, chemo- or radiotherapy) or having an unknown menopausal status due to exogenous hormone use or missing data. The 13 women (3 famine-exposed) who reported cessation of menses <12 months prior to the interview were considered to be post-menopausal. In a sensitivity analyses, we further considered them as being still premenopausal.

Socioeconomic status was categorized according to education level as low, medium and high. Current smoking status was categorized as non-smoker, former smoker or current smoker. We calculated pack years of smoking from the reported ages of starting smoking, quitting smoking (if applicable) and current age if still smoking, together with the average number of cigarettes smoked per day. This yields the total number of years of smoking the equivalent of 20 cigarettes a day. The use of other tobacco products was converted by equating 1 g of loose tobacco to one cigarette; 1 can or pack of pipe tobacco to 50 g of loose tobacco and one cigar to 5 g of tobacco.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive parameters and population characteristics were reported as mean ± SD and categorical data were expressed as percentages. Comparison of population characteristics and measures of reproductive function between the exposure categories was done using ANOVA and χ2. We built regression models to assess the association of famine exposure for exposure during any week of gestation as well as exposure during gestational weeks 1–10, 11–20, 21–30 or 31 to delivery with reproductive performance and age at natural menopause. As a respondent could be exposed to two adjacent gestational time windows, we entered each specific time window independently into the regression model, to estimate the independent effect of each gestational time period (adjusted for the effect of the other).

We used logistic regression models with control for family clustering to compare nulliparity and infertility across exposure categories. Separate models were generated for men and for women. We used a survival analysis model with competing risks and control for family clustering to investigate the association between famine exposure and age at natural menopause (Fine and Gray, 1999). Induced menopause was treated as a competing risk of natural menopause where the age at the last menses before the operation or cancer therapy was taken as the end-point. Follow-up time was in years since birth until age at natural menopause or age at last menses in women with an induced menopause. Premenopausal women were censored at the age of interview. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. We adjusted for smoking history.

To determine if any association of famine exposure with age at menopause is related to birthweight, we developed survival models with competing risk in which famine exposure and birthweight were entered jointly. Moreover, a possible interaction between birthweight and famine exposure was examined. As birthweight was not available for the sibling controls, these analyses were restricted to the hospital series.

We used SPSS for Windows, version 20.0 (SPSS INC., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA, version 11.1 (STATA Corporation, TX, USA) for all analyses.

Results

We conducted interviews with 1070 participants (477 males and 593 females). Both male and female unexposed siblings were younger than the exposed participants (Table I). Birthweight was lower among both male and female exposed participants than among the time controls. There were no differences in smoking status by famine exposure category among either males or females.

Table I.

Selected characteristics of 1070 men and women who participated in the telephone interview of the Hunger Winter Family Study, by recruitment category and gender.

| Females |

Males |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famine exposed (n = 226) | Time control (n = 181) | Sibling control (n = 186) | P-value | Famine exposed (n = 181) | Time control (n = 163) | Sibling control (n = 133) | P-value | |

| Age at interview, years ± SD | 58.7 ± 0.44 | 58.7 ± 1.6 | 56.9 ± 6.4 | <0.01 | 58.8 ± 0.42 | 58.6 ± 1.5 | 57.4 ± 6.3 | <0.01 |

| Birthweight, g ± SD | 3256 ± 514 | 3391 ± 505 | — | 0.01 | 3357 ± 500 | 3537 ± 491 | — | <0.01 |

| Age at menarche, years ± SD | 13.0 ± 1.7 | 13.0 ± 1.8 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 0.27 | na | na | na | |

| Socio-economic status | 0.06 | 0.53 | ||||||

| Low (%) | 101 (45) | 59 (33) | 76 (41) | 46 (25) | 37 (23) | 27 (20) | ||

| Medium (%) | 90 (40) | 87 (48) | 88 (47) | 77 (43) | 78 (48) | 56 (42) | ||

| High (%) | 35 (16) | 35 (19) | 22 (12) | 58 (32) | 48 (29) | 50 (38) | ||

| Never married (%) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 0.91 | 10 (6) | 7 (4) | 4 (3) | 0.56 |

| Ever smoked (%) | 139 (62) | 101 (56) | 120 (65) | 0.22 | 137 (76) | 115 (71) | 103 (77) | 0.36 |

| Pack years if ever smoking ± SD | 25.7 ± 22.0 | 23.8 ± 18.4 | 22.3 ± 18.9 | 0.38 | 29.8 ± 23.2 | 28.3 ± 26.3 | 23.8 ± 21.0 | 0.14 |

Data are shown in mean ± SD or n (%). Birthweight is not available for the siblings. na, not applicable.

Reproductive performance

Most women reported at least one pregnancy (Table II). Almost one-fifth of the women reported difficulties conceiving, with no differences across recruitment categories. The mean age at first birth was higher (P < 0.05) in the same-sex siblings compared with the exposed females. The other reproductive characteristics did not differ among the three groups. In logistic regression models (Table III), there were no significant differences between exposed and unexposed females.

Table II.

Selected measures of reproductive function among 1070 men and women who participated in the telephone interview of the Hunger Winter Family Study, by recruitment category and gender.

| Females |

Males |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Famine exposed (n = 226) | Time control (n = 181) | Sibling control (n = 186) | P-value | Famine exposed (n = 181) | Time control (n = 163) | Sibling control (n = 133) | P-value | |

| Nulliparity (%) | 21 (9) | 17 (9) | 24 (13) | 0.42 | 20 (11) | 24 (15) | 18 (14) | 0.59 |

| Difficulties conceiving (%) | 42 (19) | 37 (20) | 41 (22) | 0.68 | 29 (16.0) | 27 (17) | 20 (15) | 0.95 |

| Menopausal status | ||||||||

| Premenopausal (%) versus all others | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (18) | <0.01 | ||||

| Post-menopausal (%) versus all others | ||||||||

| Natural menopause (%) | 167 (74) | 110 (61) | 113 (61) | |||||

| Induced menopause (%) | 45 (20) | 55 (30) | 34 (18) | |||||

| Perimenopausal use of hormones (%) versus all others | 11 (5) | 16 (9) | 4 (2) | 0.02 | ||||

| Missing (%) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0.40 | ||||

| Median age at natural menopause, years [range] | 50 [35–57] | 51 [37–58] | 50 [38–58] | 0.19 | ||||

| Miscarriage or abortion (%) | 56 (25) | 44 (24) | 33 (18) | 0.18 | 32 (18)a | 22 (14)a | 16 (12)a | 0.33a |

| Preterm birth in offspring (%) | 19 (8) | 19 (11) | 20 (11) | 0.67 | 14 (8) | 14 (9) | 13 (10) | 0.82 |

| Perinatal death in offspring (%) | 8 (4) | 3 (2) | 11 (6) | 0.10 | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.51 |

| Age at first birth, years ± SD | 23.7 ± 4.0 | 23.6 ± 4.4 | 25.0 ± 4.9 | <0.01 | 26.7 ± 4.6 | 27.4 ± 5.1 | 27.1 ± 4.5 | 0.37 |

| Interval between first and second birth, years ± SDb | 3.1 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 3.0 | 2.9 ± 2.2 | 0.79 | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 3.5 ± 2.4 | 0.03 |

| Total number of children, mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 0.82 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 0.40 |

Data are shown in mean ± SD, median [range] or n (%).

aMales were asked questions that parallel the questions routinely asked of women.

bOnly calculated for women with two or more live births (n = 176, 142, 139 for famine exposed, time control, sibling control, respectively) and for men who have fathered two or more children (n = 139, 115, 100 for famine exposed, time control, sibling control, respectively). Menopausal status: percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding; induced menopause includes ovariectomy, hysterectomy, chemo- or radiotherapy.

Table III.

Association of prenatal famine exposure in females with reproductive performance compared with unexposed controls (n = 593).

| Period of gestational exposure |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed any week |

Weeks 1–10 |

Weeks 11–20 |

Weeks 21–30 |

Weeks 31 to delivery |

||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Nulliparity | ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.81 | 0.47, 1.42 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.19, 2.16 | 0.53 | 0.20, 1.43 | 1.33 | 0.62, 2.86 | 1.03 | 0.48, 2.19 | 0.57 |

| Adjusted | 0.95 | 0.53, 1.69 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.21, 2.44 | 0.58 | 0.21, 1.59 | 1.45 | 0.66, 3.17 | 1.16 | 0.53, 2.52 | 0.57 |

| Difficulties conceiving | ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.79 | 0.48, 1.29 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.21, 1.53 | 0.84 | 0.40, 1.77 | 1.69 | 0.84, 3.40 | 0.55 | 0.26, 1.20 | 0.29 |

| Adjusted | 0.78 | 0.47, 1.28 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.21, 1.56 | 0.81 | 0.38, 1.73 | 1.72 | 0.85, 3.49 | 0.54 | 0.25, 1.18 | 0.27 |

Odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI were obtained by logistic regression with correction for clustering of sibships. Adjusted for age and smoking status. P-value for test of association for all four 10-week exposure periods considered as a group (Wald test, four degrees of freedom).

Among males, neither increased prevalence of not having any children nor a higher prevalence of infertility problems was observed following famine exposure. In logistic regression analyses, neither exposure to famine in any week during gestation nor exposure during any specific period of gestation had any significant association with any of the reproductive performance parameters (data not shown). Analyses restricted to only married males and females did not alter these results (data not shown).

Age at natural menopause

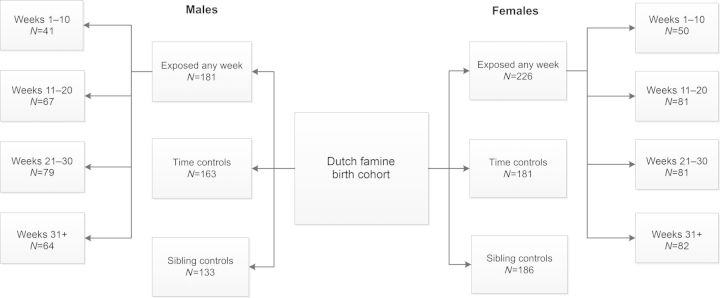

Among the 593 women, 390 (66%) had reached natural menopause. The median [range] age of natural menopause was 50 [35–59] years. The median age at natural menopause in the exposed group, the time controls and the same-sex siblings was 50 [35–57], 51 [37–58] and 50 [38–58], respectively (Table II). Reflecting the overall younger age of the sibling controls, more premenopausal women were observed in this group. The cumulative incidence of natural menopause as a function of age is presented graphically in Fig. 2, according to the survival analysis with competing risks. Women exposed to famine in utero had a 24% increase in hazard of natural menopause (95% CI 1.03, 1.51), across the life course, compared with controls after adjustment for smoking (Table IV). When the relation between famine exposure and age at menopause was analysed according to the four specific periods of gestational exposure to famine, the associations were consistent across periods, without reaching statistical significance (Table IV).

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence of natural menopause, as a function of age, with induced menopause as a competing risk. As a proportion of women do not reach natural menopause due to an induced menopause, the cumulative incidence of reaching menopause will not closely approach 1. Computed with competing-risks regression based on Fine and Gray's proportional subhazards model, by exposure to acute famine in utero (red line) compared with no exposure (blue line).

Table IV.

Survival analysis with competing risk for age at menopause in females exposed to famine compared with unexposed controls (n = 558).

| Period of gestational exposure |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed any week |

Weeks 1–10 |

Weeks 11–20 |

Weeks 21–30 |

Weeks 31 to delivery |

||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Natural menopause | ||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.25 | 1.03, 1.51 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.76, 1.37 | 1.18 | 0.89, 1.56 | 1.22 | 0.91, 1.62 | 1.12 | 0.84, 1.49 | 0.28 |

| Adjusted | 1.24 | 1.03, 1.51 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.75, 1.37 | 1.17 | 0.88, 1.55 | 1.23 | 0.92, 1.63 | 1.11 | 0.83, 1.48 | 0.29 |

HR for the risk per year of becoming post-menopausal with 95% CI with correction for clustering of sibships. Adjusted for smoking status. P-value for test of association for all four 10-week exposure periods considered as a group (Wald test, four degrees of freedom).

When the 13 women who reported cessation of menses <12 months were considered to be premenopausal, a slightly stronger association between famine exposure and age at natural menopause was observed (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05, 1.54 after adjustment for smoking status). When these 13 women were excluded from the analysis altogether, the results were similar.

When exposure to famine was defined by trimester rather than 10-week period, an association between famine exposure in each trimester and an earlier age at menopause was also observed. The association was statistically significant for third trimester exposure (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.10, 1.94 after adjustment for smoking status). This association was not attenuated by additional control for birthweight (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.04, 1.85).

Famine exposure, birthweight and age at menopause

We investigated whether the relation between famine exposure and age at natural menopause was related to birthweight (Table V). As birthweights of the sibling controls were not known, we restricted this analysis to the exposed women and their time controls with a known menopausal status (n = 376). Exposure to famine was associated with a 36% increase in the hazard of natural menopause (HR 1.36; 95% CI 1.08, 1.71), compared with controls (adjusted for smoking status). Additional adjustment for birthweight made little change in this estimate (HR1.32; 95% CI 1.05, 1.66).

Table V.

HRs for age at menopause according to birthweight and famine exposure, using survival analysis with competing risk (n = 376).

| Age at menopause |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Birthweight (kg) | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.78 | 0.62, 0.98 | 0.04 |

| Adjusted for smoking | 0.78 | 0.62, 0.99 | 0.04 |

| Adjusted for smoking and famine exposure | 0.81 | 0.64, 1.03 | 0.09 |

| Famine exposure: any week | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.38 | 1.09, 1.73 | 0.01 |

| Adjusted for smoking | 1.36 | 1.08, 1.71 | 0.01 |

| Adjusted for smoking and birthweight | 1.32 | 1.05, 1.66 | 0.02 |

HR for the risk per year of becoming post-menopausal with 95% CI.

Each kilogram increase in birthweight was associated with a 22% decrease in the hazard of natural menopause (HR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62, 0.98) and adjustment for smoking did not change this estimate. When famine exposure was added to the model, the relation between birthweight and age at menopause showed little change (HR 0.81) but was no longer statistically significant (95% CI 0.64, 1.03). In these models, birthweight and exposure to famine did not show a significant interaction (P = 0.33).

Discussion

This large population-based study demonstrates that prenatal famine exposure is not associated with later characteristics of reproductive performance in men or women.

Famine exposed women were 24% more likely to experience natural menopause at any age (95% CI 1.03, 1.51; P = 0.03) as estimated from survival models with induced menopause as competing risk. This suggests a direct relationship between prenatal famine exposure and the age of menopause. The association was not attenuated by additional control for birthweight.

Little is known about the influence of the environment encountered during fetal life on the reproductive function in human adult life. Our findings on measures of reproductive performance confirm the findings by Lumey and Stein (1997). Our results are in contrast however with the findings of Painter et al. (2008) who reported an increase in reproductive success in women exposed to famine. These inconsistent findings are based on largely the same famine exposed females born in the Wilhelmina Gasthuis Hospital in Amsterdam, but the two studies utilized different reference populations. As the estimates from the two studies have overlapping CIs, the inconsistencies may also reflect chance variation around an overall weak association.

In the animal kingdom, the importance of prenatal nutrition for reproductive function is well recognized. A reduction of lifetime reproductive capacity after prenatal undernutrition has been reported in mice (Meikle and Westberg, 2001) and sheep (Rae et al., 2002). Another study recently found evidence that prenatal dietary restriction influences ovarian reserve in the bovine model (Mossa et al., 2013); first trimester caloric restriction resulted in offspring with diminished ovarian reserve, as assessed by higher follicle-stimulating hormone levels, lower Anti-Müllerian hormone levels and a reduction in the antral follicle count, compared with offspring from adequately fed mothers.

The literature on the relation between undernutrition in utero and age at menopause is limited. Elias et al. (2003) reported a decrease of 0.36 years in age at natural menopause following famine exposure during early childhood. More frequently reported are studies that assess the association between birthweight, taken as a proxy for intrauterine nutritional status, and subsequent age at menopause. Steiner et al. (2010) reported a weak association between birthweight and age at menopause (HR 1.09; 95% CI 0.99, 1.20). In our study this relation was attenuated after adjustment for gestational exposure to famine, suggesting that exposure to prenatal famine may affect the age at menopause through its impact on birthweight.

The association between birthweight and subsequent age at menopause has not been observed unanimously, however, as Treloar et al. (2000) did not find any association between birthweight and subsequent age at menopause in twins. Two other studies also failed to show an association for birthweight, but did find menopause to occur earlier in women with a low weight at the age of 1 (Cresswell et al., 1997) or 2 years (Hardy and Kuh, 2002).

The literature on the effects of famine on male reproductive performance is scarce. The analyses concerning gestational famine exposure and male reproductive performance were therefore primarily hypothesis generating. Developmental problems of the testis such as cryptorchidism are associated with reduced fertility in adult life. The exact mechanisms that regulate the testicular descent are unknown, but may involve endocrine, genetic and environmental factors. Conditions such as low birthweight, prematurity and small for gestational age are associated with a higher prevalence of cryptorchidism (Klonisch et al., 2004; Hutson et al., 2013; Lee and Houk, 2013). In our study, no evidence for a possible association of maternal undernutrition with male reproductive performance was found.

A strength of our study is the population-based design. Individuals were recruited from institutional birth records on the basis of their place and date of birth, irrespective of their health status. The timing of exposure was based on the gestational age relative to the LMP. Another strength is the use of same-sex siblings as controls, as they can be used to correct for any genetic predisposition.

With regard to the response rate of eligible participants, 9% of the 3307 individuals selected for follow-up at the birth clinics were no longer alive, 8% had emigrated and 13% could not be located at age 58 years. All others were invited by mail to join the study. There was no association between famine exposure and follow-up status at age 58 years. We found no differences in birth characteristics or demographic characteristics by follow-up status at age 58 or by comparing responders and non-responders to our invitation letter (Lumey et al., 2007). Therefore, we do not think that selection bias related to early mortality or to other reasons for non-response could explain our study results.

Although several studies have been published that find evidence for lifestyle factors besides smoking in relation to age at natural menopause (Harlow and Signorello, 2000; Gold et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2012), we considered only smoking as a possible confounder. As women were interviewed at the mean age of 58 years, all life-style factors were measured after menopause had already occurred. As menopause may lead to changes in life style and behaviour, it would not be appropriate to control for these factors. Smoking is an exception, because virtually all smokers start smoking as young adults, and smoking status has been consistently associated with menopause (Gold et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2012).

A limitation is that information on reproductive performance was obtained from the participants themselves. Prolonged time to pregnancy is a commonly used measure for subfertility (Baird et al., 1986; Greenhall and Vessey, 1990; Akre et al., 1999; Joffe, 2000). As exact information regarding time to pregnancy was not available, we used ‘difficulties conceiving exceeding 12 months duration’ as a proxy.

The use of nulliparity as a marker of reproductive performance combines both physiological incapacity and intention and we did not ascertain voluntary childlessness or use of contraception. To the extent that reproductive choices are not influenced by exposure to famine, this will not have biased our results.

Fertility selection might be a factor in this study. During the famine, conception rates went down and those women who did conceive were possibly more fertile, creating offspring who are themselves more fertile. The use of sibling controls is likely to adjust for this factor.

We asked women to report their age (in completed years) at menopause, and coded the information accordingly. The use of a woman's recall of age at natural menopause is a widely accepted method, but this measure does not have perfect reliability and validity (McKinlay and McKinlay, 1973; Colditz et al., 1987; de Tonkelaar, 1997; Hahn et al., 1997; Clavel-Chapelon and Dormoy-Mortier, 1998). Recall bias might lead to inaccuracy in age at menopause at the individual level, but the bias is unlikely to be differential across exposure groups, and as such it would only attenuate measures of association with age at menopause but not explain the present finding of differences in age at menopause between exposure groups.

That we did not find a difference in the median age at menopause, but did find that famine exposed women were more likely to be post-menopausal at any given age could be explained by the use of a survival analysis with competing risk, which accounts for imbalances between the exposure categories in terms of an induced menopause and the proportion of women who had not yet reached menopause.

Female reproduction requires both quality and quantity of the oocytes residing within the ovarian follicles. A woman receives her endowment of oocytes during fetal development and during the reproductive years, the quantity of the follicle pool declines. Next to the decrease in quantity, the oocyte quality demonstrates changes with increasing age, which becomes apparent in increased aneuploidy rates leading to a higher prevalence of miscarriage and infertility observed at older ages (Thum et al., 2008).

Our study population comprises a generation of women who were relatively young while giving birth to their first child and therefore might not experience the detrimental effects of reproductive ageing in terms of oocyte quality. Another possibility is that prenatal caloric restriction impairs the endowment of primordial follicles and in a way that results in an already smaller fetal ovarian reserve. If we look at the phenomenon of menopause, when fewer than 1000 follicles are left, the final cessation of menses will occur and therefore menopause is primarily dictated by the quantity of the ovarian follicles (Faddy, 2000). This could explain our observation that menopause occurs earlier in famine-exposed women compared with unexposed women. And this observation suggests that next to post-natal factors such as smoking, there is room for prenatal factors in the understanding of the female reproductive ageing process.

The reported menopausal ages are well within the normal range, 40–60 years, with a median age of 51 years (Treloar, 1981; de Velde and Pearson, 2002). No differences were observed between exposed and unexposed women in the incidence of premature (before 40 years) or early (between 40–45 years) menopause. However, the observation that menopause occurs earlier in famine-exposed women compared with unexposed women, does support the theory that prenatal factors can influence reproductive lifespan in later life. The exact knowledge of the process through which maternal undernutrition affects reproductive ageing in the offspring remains very limited and justifies further studies on this subject.

In conclusion, we did not find clinical evidence that prenatal famine exposure affects a range of measures of reproductive performance in males or females. However, evidence for an earlier menopause in women exposed to famine in utero was obtained, suggesting that environmental circumstances early in life might influence the pattern of endowment or the rate of decline of the ovarian follicle pool.

Authors' roles

F.Y. wrote the final manuscript and carried out all necessary data analyses. F.B. and E.V. participated in interpretation of the data and provided significant revisions. L.H.L. and A.S. designed the study, supervised the data acquisition, carried out preliminary analyses and participated in the interpretation of study findings. L.H.L. obtained study funding. K.P. and Y.S. wrote the initial manuscript and carried out preliminary data analyses. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the NHLBI/NIH (HL-067914).

Conflict of interest

F.Y., K.P., Y.S., E.V., A.S. and L.H.L have nothing to declare. F.B. is a member of the external advisory board for Merck Serono, The Netherlands, and a member of the advisory board for Roche, Switzerland, does consultancy work for MSD, the Netherlands and Gedeon Richter, Belgium and performs educational activities for Ferring BV, the Netherlands and MSD, the Netherlands.

References

- Akre O, Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Kvist U, Trichopoulos D, Ekbom A. Human fertility does not decline: evidence from Sweden. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:1066–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR. Use of time to pregnancy to study environmental exposures. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:470–480. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1995;311:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:465–493. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger GC, Drummond JC, Stanstead HR. Malnutrition and Starvation in Western Netherlands, September 1944–July 1945. Parts I and II. Hague, The Netherlands: Staatsuitgeverij; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Clavel-Chapelon F, Dormoy-Mortier N. A validation study on status and age of natural menopause reported in the E3N cohort. Maturitas. 1998;29:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Stason WB, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:319–325. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JL, Egger P, Fall CH, Osmond C, Fraser RB, Barker DJ. Is the age of menopause determined in-utero? Early Hum Dev. 1997;49:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(97)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin JP, Dorland M, Bruinse HW, Spliet W, Nikkels PG, te Velde ER. Fetal growth retardation as a cause of impaired ovarian development. Early Hum Dev. 1998;51:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(97)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Keyser N, Josefsson A, Bladh M, Carstensen J, Finnstrom O, Sydsjo G. Premature birth and low birthweight are associated with a lower rate of reproduction in adulthood: a Swedish population-based registry study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1170–1178. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Tonkelaar I. Validity and reproducibility of self-reported age at menopause in women participating in the DOM-project. Maturitas. 1997;27:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)01122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias SG, van Noord PA, Peeters PH, den TI, Grobbee DE. Caloric restriction reduces age at menopause: the effect of the 1944–1945 Dutch famine. Menopause. 2003;10:399–405. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000059862.93639.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ. Follicle dynamics during ovarian ageing. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;163:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, Samuels S, Greendale GA, Harlow SD, Skurnick J. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:865–874. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.9.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhall E, Vessey M. The prevalence of subfertility: a review of the current confusion and a report of two new studies. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:978–983. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53990-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn RA, Eaker E, Rolka H. Reliability of reported age at menopause. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:771–775. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Kuh D. Does early growth influence timing of the menopause? Evidence from a British birth cohort. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2474–2479. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.9.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, Signorello LB. Factors associated with early menopause. Maturitas. 2000;35:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson JM, Southwell BR, Li R, Lie G, Ismail K, Harisis G, Chen N. The regulation of testicular descent and the effects of cryptorchidism. Endocr Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1089. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe M. Time trends in biological fertility in Britain. Lancet. 2000;355:1961–1965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02328-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonisch T, Fowler PA, Hombach-Klonisch S. Molecular and genetic regulation of testis descent and external genitalia development. Dev Biol. 2004;270:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PA, Houk CP. Cryptorchidism. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:210–216. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835ffc7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumey LH, Stein AD. In utero exposure to famine and subsequent fertility: The Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1962–1966. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumey LH, Van Poppel FW. The Dutch famine of 1944–45: mortality and morbidity in past and present generations. Soc Hist Med. 1994;7:229–246. doi: 10.1093/shm/7.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumey LH, Stein AD, Kahn HS, van der Pal-de Bruin KM, Blauw GJ, Zybert PA, Susser ES. Cohort profile: the Dutch Hunger Winter families study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1196–1204. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumey LH, Stein AD, Kahn HS, Romijn JA. Lipid profiles in middle-aged men and women after famine exposure during gestation: the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1737–1743. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay SM, McKinlay JB. Selected studies of the menopause. J Biosoc Sci. 1973;5:533–555. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000009391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle D, Westberg M. Maternal nutrition and reproduction of daughters in wild house mice (Mus musculus) Reproduction. 2001;122:437–442. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DH, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, McFadden E, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. Body mass index, exercise, and other lifestyle factors in relation to age at natural menopause: analyses from the breakthrough generations study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:998–1005. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossa F, Carter F, Walsh SW, Kenny DA, Smith GW, Ireland JL, Hildebrandt TB, Lonergan P, Ireland JJ, Evans AC. Maternal undernutrition in cows impairs ovarian and cardiovascular systems in their offspring. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:92. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.107235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter RC, Westendorp RG, de R, Sr, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Roseboom TJ. Increased reproductive success of women after prenatal undernutrition. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2591–2595. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae MT, Kyle CE, Miller DW, Hammond AJ, Brooks AN, Rhind SM. The effects of undernutrition, in utero, on reproductive function in adult male and female sheep. Anim Reprod Sci. 2002;72:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(02)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindram IS. Effects of undernourishment on fetal growth. Ned Tijdschr Verloskd Gynaecol. 1953;53:30–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira A. The decline of fecundity with age. Maturitas. 1988;10(Suppl. 1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(88)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein Z, Susser M. Fertility, fecundity, famine: food rations in the dutch famine 1944/5 have a causal relation to fertility, and probably to fecundity. Hum Biol. 1975a;47:131–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein Z, Susser M. The Dutch famine, 1944–1945, and the reproductive process. I. Effects on six indices at birth. Pediatr Res. 1975b;9:70–76. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein Z, Susser M, Saenger G, Marolla F. Famine and Human Development. The Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944–1945. New York: Oxford University Press: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Stein AD, Ravelli AC, Lumey LH. Famine, third-trimester pregnancy weight gain, and intrauterine growth: the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Hum Biol. 1995;67:135–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein AD, Zybert PA, van de BM, Lumey LH. Intrauterine famine exposure and body proportions at birth: the Dutch Hunger Winter. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:831–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner AZ, D'Aloisio AA, DeRoo LA, Sandler DP, Baird DD. Association of intrauterine and early-life exposures with age at menopause in the Sister Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:140–148. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk L, Perry JR, Chasman DI, He C, Mangino M, Sulem P, Barbalic M, Broer L, Byrne EM, Ernst F, et al. Meta-analyses identify 13 loci associated with age at menopause and highlight DNA repair and immune pathways. Nat Genet. 2012;44:260–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Tan L, Yang F, Luo Y, Li X, Deng HW, Dvornyk V. Meta-analysis suggests that smoking is associated with an increased risk of early natural menopause. Menopause. 2012;19:126–132. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318224f9ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy GK, Ostbye T, Skjaerven R. Association of preterm birth with long-term survival, reproduction, and next-generation preterm birth. JAMA. 2008;299:1429–1436. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.12.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Velde ER, Pearson PL. The variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:141–154. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thum MY, Abdalla HI, Taylor D. Relationship between women's age and basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels with aneuploidy risk in in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar AE. Menstrual cyclicity and the pre-menopause. Maturitas. 1981;3:249–264. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(81)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar SA, Sadrzadeh S, Do KA, Martin NG, Lambalk CB. Birth weight and age at menopause in Australian female twin pairs: exploration of the fetal origin hypothesis. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:55–59. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trienekens G. The food supply in the Netherlands during the Second World War. International and Comparative Perspectives. In: Smith DF, Philips J, editors. Food, Science, Policy and Regulation in the Twentieth Century. London: Routledge; 2000. pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Voorhuis M, Onland-Moret NC, van der Schouw YT, Fauser BC, Broekmans FJ. Human studies on genetics of the age at natural menopause: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:364–377. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JW. Fecundity and natural fertility in humans. Oxf Rev Reprod Biol. 1989;11:61–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]