Abstract

Many insular taxa possess extraordinary abilities to disperse but may differ in their abilities to diversify and compete. While some taxa are widespread across archipelagos, others have disjunct (relictual) populations. These types of taxa, exemplified in the literature by selections of unrelated taxa, have been interpreted as representing a continuum of expansions and contractions (i.e. taxon cycles). Here, we use molecular data of 35 out of 40 species of the avian genus Pachycephala (including 54 out of 66 taxa in Pachycephala pectoralis (sensu lato), to assess the spatio-temporal evolution of the group. We also include data on species distributions, morphology, habitat and elevational ranges to test a number of predictions associated with the taxon-cycle hypothesis. We demonstrate that relictual species persist on the largest and highest islands across the Indo-Pacific, whereas recent archipelago expansions resulted in colonization of all islands in a region. For co-occurring island taxa, the earliest colonists generally inhabit the interior and highest parts of an island, with little spatial overlap with later colonists. Collectively, our data support the idea that taxa continuously pass through phases of expansions and contractions (i.e. taxon cycles).

Keywords: Australo-Papua, coexistence, community assembly, island biogeography, molecular phylogeny, Wallacea

1. Introduction

Differentiation of bird populations on oceanic islands and archipelagos has played an important role for the understanding of colonization and diversification of biological communities [1–8]. Although modified and extended in later publications [9–13], many of the early ecological and biogeographic ideas and theories have left a great legacy. In this respect, the Indo-Pacific island region, which includes the archipelagos of Wallacea and the western Pacific, has been particularly important. Alfred Russel Wallace spent 8 years exploring these islands and later summarized his knowledge and thoughts on the connection between geography and animal distributions in what came to be the first major modern biogeographic synthesis [2].

Since Wallace's explorations, numerous other researchers have tested key biogeographic concepts in the Indo-Pacific [3,4,7,8]. Based on geographical distributions of the insular ant fauna in Melanesia, Edward O. Wilson [14,15] suggested historical taxon cycles as a mechanistic cause behind the contemporary distribution of the Melanesian ant fauna. Subsequently, other distributional studies [16–20] corroborated this idea of recurring expansions and contractions. Taxon cycles were generally described as consisting of four main stages [19–21]: an initial expansion stage (I) in which a taxon colonizes all islands within an archipelago(s), but largely confined to coastal habitats. In the next stage (II), geographical expansion slows down and phenotypic differentiation takes place. At this stage, differentiated populations become more specialized and start to inhabit higher elevations. In the next stage (III), populations on the smallest islands begin to become extinct, and in the final stage (IV), the distributional range has contracted dramatically and only populations on a few (or single) large and topographically high islands persist leaving a signature of relictual distribution. What actually causes these expansions and contractions is unknown, but it has been speculated that they are caused by coevolution with enemy populations [22] or pathogens [23].

The different states in the taxon cycles were in most cases described using examples from unrelated taxa and were based on conventional taxonomic assignments. Molecular advances now allow for constructing phylogenies that reflect the relative timing of evolutionary and biogeographic events. However, the taxon-cycle hypothesis has not often been investigated with these modern approaches (but see, refs. [23,24]). While taxon cycles probably also occur on continents [23], the geographical configuration of islands and archipelagos reveal more clearly their presence. The island-rich Indo-Pacific therefore provides an ideal setting for testing the taxon-cycle hypothesis.

Here, we focus on the passerine bird genus Pachycephala, which originated in Australo-Papua and later colonized the Indonesian and Philippine archipelagos to the west and the Pacific archipelagos to the east [25,26]. We focus on the parts of the island region with relatively simple geological history surrounding the area of origin, and thus exclude Borneo, Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi and the Philippines. We generated both nuclear and mitochondrial molecular data for 35 of the 40 Pachycephala species. Additionally, we included molecular data for 54 of the 66 subspecies of Pachycephala pectoralis (sensu lato).

Within our densely sampled and robust molecular framework, we delineate the evolutionary units within Pachycephala and determine the origin, directionality and relative timing of dispersal for the group. We use this phylogenetic framework along with data on distributions, morphology, habitat and elevation to explicitly test predictions associated with taxa that undergo continuous expansions and contractions (i.e. taxon cycles). We expect that: (i) recent colonizers representing early stages in the taxon cycle are present in many often well-differentiated forms in each archipelago within the Indo-Pacific, (ii) old relictual taxa are present on only the largest and highest islands across the Indo-Pacific, and (iii) when an expanding taxon colonizes an island and now co-occurs with an older lineage, that the expanding lineage occupies disturbed/low-elevation habitat at the expense of the older lineage, which contracts to undisturbed/high-elevation habitats. In cases of overlap in habitat and altitudinal distribution, we further expect segregation in morphospace.

2. Material and methods

(a). Taxon sampling

Our study included molecular data of 35 Pachycephala species [27], (242 individuals) and 54 P. pectoralis s.l. subspecies (208 individuals). For subspecies that occur on several islands, we included as many island populations as possible. Thus, the taxon sampling for islands in Wallacea and the western Pacific is particularly dense and greatly surpasses the geographical sampling of previous studies [25,28,29]. We used Coracornis sanghirensis, Coracornis raveni, Melanorectes nigrescens and Collurincincla harmonica as out-groups. All new sequences are deposited on GenBank (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1).

For 240 out of 242 samples, one or two mitochondrial regions were sequenced, the complete NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2, 1041 bp) and 3 (ND3, 351 bp). For 80 out of 242 samples, representing taxa from all major clades, we also obtained sequences from two nuclear introns, 299 bp of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphodehydrogenase (GAPDH) intron 11 and 609 bp of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) introns 6–7.

For fresh tissue, the target markers were amplified in one fragment, while archaic DNA from footpad samples from study skins collected between 1875 and 1968 were amplified and sequenced in short fragments (less than 200 bp). Several new primers were designed for this purpose (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2). All coding sequences were checked for stop codons and indels that may have disrupted the reading frame.

(b). Phylogenetic analyses and dating

We used maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference to estimate the phylogenetic relationships within Pachycephala using the most appropriate substitution model for each partition as estimated by Modeltest v. 3.07 [30] following the Akaike information criterion (Myo: TVMef; GAPDH + I + Γ, ODC: HKY + Γ, ND2: GTR + I + Γ, ND3: GTR + I + Γ). We analysed each gene separately and finally analysed the concatenated dataset applying the appropriate model to each partition. The maximum-likelihood analysis was run in GARLI v. 2.0 [31] for 50 million generations and Bayesian analyses were run in MrBayes v. 3.1.2 for 50 million generations [32,33] and in BEAST v. 1.7.3 [34] for 100 million generations. To obtain a relatively dated tree, we set the age of origin of Pachycephala to an arbitrary 10. We assumed a birth–death speciation process for the tree prior and an uncorrelated lognormal distribution for the molecular clock model [35]. We used default prior distributions for all other parameters and ran Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains for 100 million generations sampling every 1000th generation to produce a posterior distribution of 100 000 trees. We discarded half of these trees as burn-in and summarized the posterior distribution as a maximum clade credibility tree. All analyses were repeated multiple times and convergence diagnostics were assessed using TRACER [36] (checking that effective sample size values for all parameters were higher than 100 suggesting little autocorrelation between samples) and AWTY [37].

(c). Ancestral area reconstruction

We used LAGRANGE [38,39] to estimate ancestral areas within Pachycephala. We assigned nine geographical areas for the LAGRANGE analysis after considering the geological history of the region [40,41] as follows: Australia, New Guinea, Moluccas, Sulawesi, Philippines, Greater Sundas, Lesser Sundas, Melanesia and Polynesia. We randomly selected 1000 trees from the posterior distribution of the BEAST analysis of the concatenated dataset and ran LAGRANGE on each of these trees. The frequency of the most likely ancestral areas for clades was plotted as marginal distributions on the majority-rule consensus tree derived from the BEAST MCMC, recording the area (maxareas = 2) with the highest relative probability for each node.

(d). Habitat, altitude and morphology of sympatric island taxa

To examine the history of morphological variation among sympatric Pachycephala island taxa, we measured 2–24 individuals (in total, 263 individuals) per taxon. The characters examined (wing length, tail, tarsus and middle toe, and the length, width and depth of the culmen measured at the base) are believed to represent various aspects of adaptation to differences in habitat use and foraging strategies [42,43]. All measurements were taken by K.A.J. and Tobias Jørgensen at the American Museum of Natural History, the British Museum of Natural History, the Museum of Zoology Bogor, the Zoological Museum Berlin and the Zoological Museum, Natural History Museum of Denmark. All values were log transformed to obtain homogeneous variances between traits with different means, and a principal component analysis (PCA; prcomp command in R v. 3.0.0 [44]) was used to reduce dimensionality of our dataset. The significance of differences in the morphospace occupied by sympatric taxa was tested using the permutational MANOVA approach [45], using the ‘vegan’ package [46]. For each island, the pairwise Euclidean distances in morphological space (based on the first two PCs) were recorded for all specimens and differences between taxa tested by including species as a factor in the MANOVA model. The significance of test results was based on the sequential sums of squares of 10 000 random permutations. For all sympatric island taxa, we also collected data on altitudinal distribution and habitat from Boles [47].

(e). Testing for an association between old relictual taxa and island size

As continental taxon cycles are likely to be confounded by alternative ecological and evolutionary processes, we focused on the island regions surrounding New Guinea, which have no close connections with continental Asia. We refer to this dataset as the ‘oceanic islands’ dataset. Consequently, the study region west of New Guinea includes the Lesser Sunda Islands and Moluccas but excludes Sulawesi and the Philippines, and the region east of New Guinea includes the islands of Melanesia and Polynesia except for New Zealand and Hawaii.

We compiled a list of the largest and highest islands in the archipelagos to the west (Wallacea) and to the east (Pacific) of New Guinea. Large and high islands are particularly interesting for taxon-cycle hypothesis testing because they might represent potential refugia where contracting taxa would persist in stages III and IV of the taxon cycle.

We quantified the age of all Pachycephala taxa inhabiting the oceanic islands using the root distance, based on the number of nodes within the phylogeny between the root and the taxon tip for each taxon (after pruning the phylogeny to remove taxa not found within these islands). We then divided all the taxa into two groups: an ‘old group’ and a ‘young group’, based on an arbitrary root distance split. To avoid subjectivity, all root distance splits were tested. The area and elevation of the island inhabited by each taxon was recorded. If a taxon was found on more than one island, then the maximum island size was used. The observed difference between island sizes for the two groups was quantified using the sum of the ranks of island size; subtracting the ‘young group’ sum of ranks from the ‘old group’ sum of ranks. The significance of the observed difference between groups was tested against a null hypothesis that island area (or elevation) is not associated with taxon root distance, using a simple null model where the tips of the pruned phylogeny were randomly shuffled. One thousand null results were produced and the significance of the observed result calculated as the proportion of null values greater than the observed value. These tests were performed for both island area and for island elevation. Null model tests were performed using the R statistical programming language [44], using the package ‘adephylo’ [48].

3. Results

(a). Phylogenetic relationships and taxonomy

Analyses of the individual gene partitions were congruent for all well-supported relationships across phylogenetic methodologies. The two nuclear loci provided little resolution on recent time scales but raised support values for some basal relationships. Analysis of the concatenated datasets in BEAST (figure 1), GARLI (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1) and MrBayes (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2) were congruent for all but two well-supported relationships: (i) analysis in BEAST recovered P. citreogaster rosseliana and P. c. collaris as a basal lineage within groups A–F, whereas analyses in MrBayes and GARLI placed these two taxa outside of groups A–H, and (ii) analysis in BEAST recovered P. macrorhynca arthuri as the basal most member of a subclade within clade G, which included Australo-Papuan and eastern Lesser Sundan taxa, whereas analyses in Mrbayes and GARLI recovered P. macrorhynca arthuri as the sister lineage of P. fulvotincta. The phylogenetic hypothesis suggests that the P. pectoralis s.l. complex is not monophyletic. However, monophyly of the majority of the recognized taxa at subspecies level was highly supported. Consequently, a thorough taxonomic revision for the whole Pachycephala is warranted.

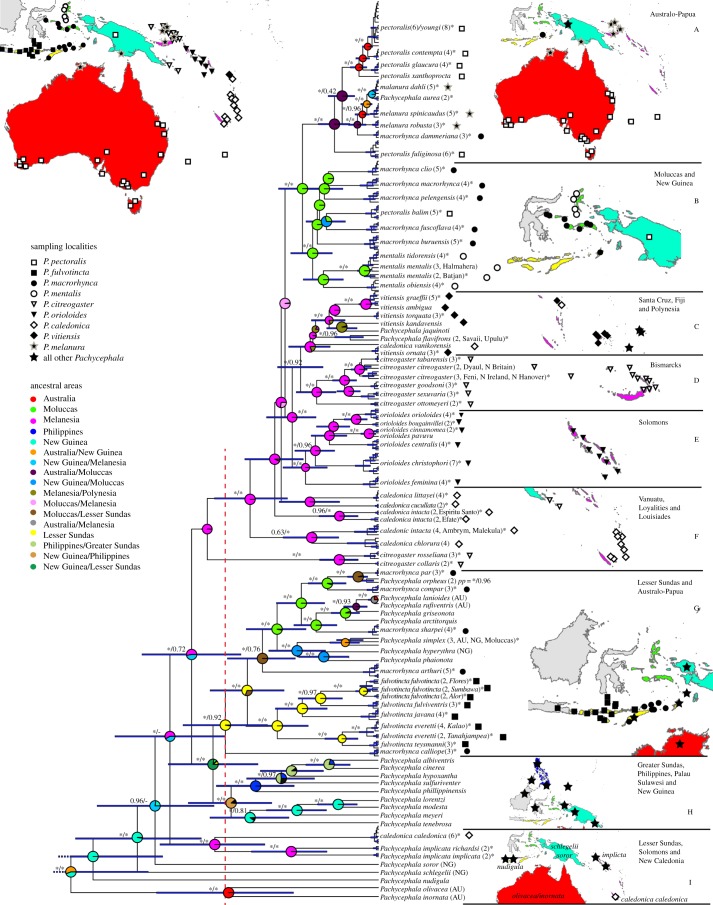

Figure 1.

Estimate of phylogenetic relationships, relative divergence times (BEAST) and ancestral area reconstructions (LAGRANGE) of Pachycephala. Members of P. pectoralis (sensu lato) are indicated by signs following the taxon name, based on the species groups suggested by Galbraith [49]. Support values are indicated to the left of internodes and after the taxon name, and represent posterior probabilities (PP) (asterisk (*) indicates PP = 1.00) from the analysis in BEAST of the concatenated dataset (two nuclear and two mitochondrial genes) and the mitochondrial dataset (ND2 and ND3). Support values are only indicated if at least one analysis provides a posterior probability of 0.95 or higher. The map in the upper left corner indicates sampling localities included in the study, with colours representing the regions according to the ancestral area analysis. Maps to the right of each major clade show sampling localities for all individuals in the group. Pie charts at internodes indicate the probability of the area of origin coloured according to the ‘ancestral areas’ legend. The red dotted vertical line denotes half-time between the origin of Pachycephala and the present.

(b). Spatio-temporal biogeographic analyses

We produced a chronogram of Pachycephala with relative diversification dates. In an attempt to delineate the relatively young and old lineages, we split the tree into a younger and an older half (figure 1, red dotted line). This allowed us to identify old relictual taxa (stage IV) and young expanding taxa (stages I and II). Any older point in time will delineate fewer older lineages and any more recent point in time will delineate more older lineages.

At the half-time point, 11 lineages existed. Three of these lineages were taxon-rich and widespread (clades A–E and some lineages of group F, clade G excluding P. m. calliope and clade H). The other eight lineages contained only one or a few named taxa (table 1). Five lineages contained one or two taxa that occur on single islands: P. c. rosseliana/collaris on the Louisiades, P. calliope on Timor, P. caledonica caledonica of New Caledonia, P. implicata (two subspecies) on Bougainville and Guadalcanal and P. nudigula (two subspecies) on Flores and Sumbawa. Another two lineages—Pachycephala soror (five subspecies) and Pachycephala schlegelii (three subspecies)—included taxa endemic to the interior montane forests of New Guinea. Finally, one lineage, which included P. olivacea (five subspecies), P. inornata (monotypic) and P. rufogularis (monotypic, not included in this study), occurs in arid habitat in southern Australia and forests of southeastern Australia.

Table 1.

The eight oldest taxon-poor lineages as identified by the chronogram in figure 1 and the null models in the electronic supplementary material, figure S3 and their contemporary distributions. (These lineages represent relictual taxa and may correspond to taxon cycle stage IV. Also indicated are altitudinal distributions (L =<200 m.a.s.l., M = 200–1000 m.a.s.l., H >1000 m.a.s.l.) and preferred habit requirements (A, all habitats; UF, undisturbed forest; DF, disturbed forest (incl. edge and woodland); CH, coastal habitat; SL, scrubland).)

| taxa | distribution | altitudinal distribution | habitat |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. c. rosseliana/collaris | Louisiades, SE New Guinea | L/M? | ? |

| P. m. calliope | Timor | L/M/H | UF/DF |

| P. c. caledonica | Grande Terre, New Caledonia | L/M/H | UF |

| P. implicata | Bougainville/Guadalcanal | H | UF |

| P. soror | New Guinea | H | UF/DF |

| P. schlegelii | New Guinea | H | UF/DF |

| P. nudigula | Flores/Sumbawa | H | UF |

| P. olivacea/inornata | Australia | L/M/H | A |

(c). Ancestral area analysis

The ancestral area analysis suggests that Pachycephala originated in Australo-Papua and that New Guinea in particular was an important area for the early diversification of the group (figure 1). There is a strong signature of a Melanesian origin of the lineages branching off to clades A–H. This is followed by colonization of the Moluccas (clade B) and back-colonization to Australia (clade A). The analysis suggests that both Melanesia and Wallacea were colonized multiple times.

(d). Island attributes and habitat and morphology of sympatric island taxa

We identified the largest and highest islands within the oceanic islands region and compiled data for all islands with elevations up to 2000 metres above sea level (m.a.s.l.) (table 2). Four of the five insular species-poor lineages occur on some of these large and high islands (table 2) and only P. c. rosseliana/collaris occur on small and low islands. Apart from New Guinea, no other islands in the Pacific are inhabited by more than one form of Pachycephala. In Wallacea, however, members of Pachycephala co-occur on many islands. For example, P. griseonota co-occurs with P. pectoralis s.l. on Halmahera, Batjan, Ternate, Obi, the Sula islands, Ambon, Seram and Buru.

Table 2.

Largest islands within Wallacea (excl. Sulawesi) and the Pacific (excl. New Zealand and Hawaii) east and west of New Guinea. (The list ranks the islands according to size and includes all islands with maximum elevations higher than 1000 m.a.s.l. To the right is indicated the distribution of the taxa that represent relictual taxon-cycle stage IV taxa as indicated in table 1 and the younger sympatric island taxon. In parentheses following the taxon names are indicated the altitudinal distribution and habitat for each taxon as in table 1. According to the taxon-cycle hypothesis, older colonizers are expected to inhabit more specialized and inland habitats at higher elevations, whereas recent colonizers are expected to inhabit lower elevations and broader habitat types. Note that P. c. rosseliana occurs on a small and low island (Rossel Island, 200 km to the southeast of New Guinea), and therefore falls outside the expected late stage taxon-cycle pattern.)

| Pacific |

sympatric taxa in the Pacific |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| islands | area (km2) | max island elevation (m) | old lineages | young lineages |

| New Britain | 36 520 | 2334 | ||

| Grande Terre, New Caledonia | 16 648 | 1628 | P. c. caledonica (L/M/H; UF/DF) | P. rufiventris xanthetraea (L/M; DF/SL) |

| New Ireland | 13 570 | 2379 | ||

| Viti Levu | 10 531 | 1324 | ||

| Bougainville | 9318 | 2716 | P. implicata richardsi (H; UF/DF) | P. orioloides bougainvillei (M/H; UF/DF) |

| Vanua Levu | 5587 | 1032 | ||

| 5302 | 2330 | P. implicata implicata (H; UF/DF) | P. orioloides cinnamomea (M/H; UF/DF) | |

| other islands higher than 2000 m | ||||

| Ferguson | 1266 | 2072 | ||

| Goodenough | 662 | 2536 | ||

| Wallacea (excl. Sulawesi) |

sympatric taxa in Wallacea |

|||

| islands | area (km2) | max elevation (m) | old lineages | young lineages |

| Timor | 30 777 | 2963 | P. m. calliope (L/M/H; A) | P. orpheus (L/M/H; A) |

| Halmahera | 17 780 | 1635 | ||

| Seram | 17 148 | 3027 | ||

| Sumbawa | 15 448 | 2821 | P. nudigula ilsa (M/H; UF) | P. fulvotincta fulvotincta (L/M/H; A) |

| Flores | 14 300 | 2382 | P. nudigula nudigula (M/H; UF) | P. fulvotincta fulvotincta (L/M/H; A) |

| Sumba | 11 153 | 1225 | ||

| Buru | 9505 | 2736 | ||

| Bali | 5561 | 3142 | ||

| Lombok | 5435 | 3726 | ||

| other islands higher than 2000 m | ||||

| Batjan | 1900 | 2120 | ||

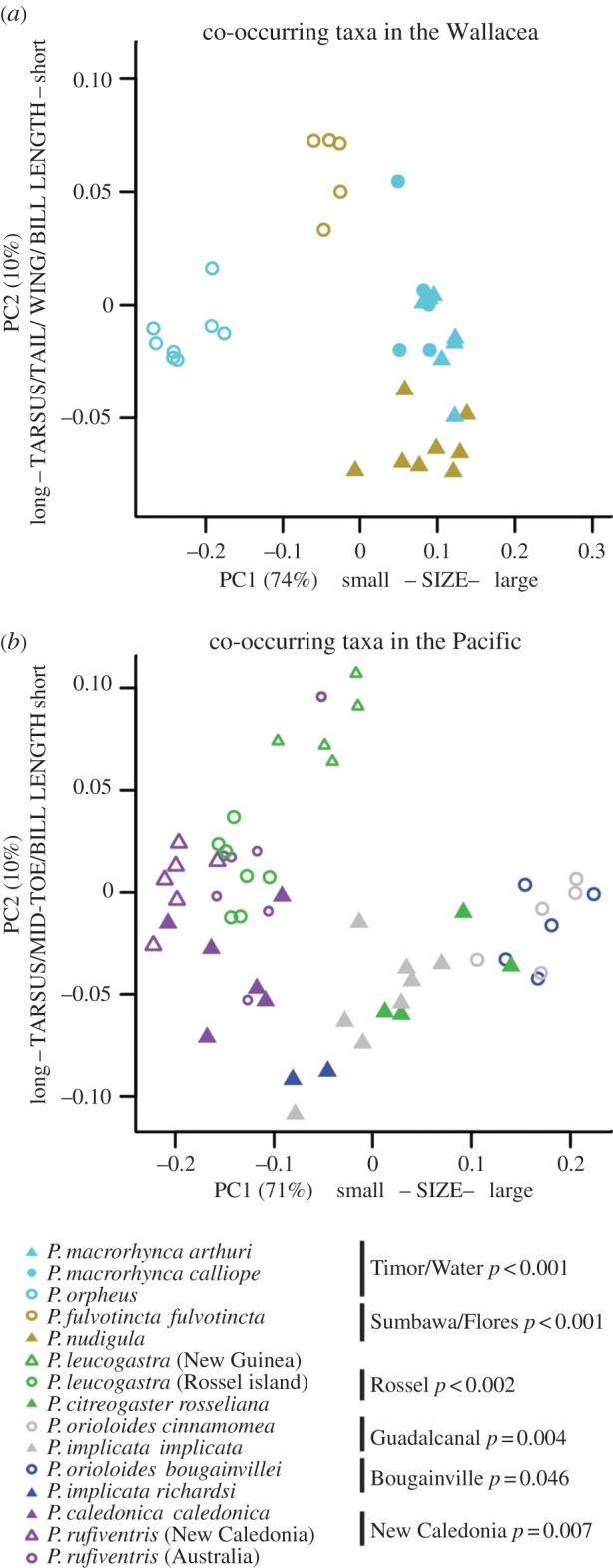

Analysis of the morphological space occupied by sympatric Pachycephala taxa in the insular regions to the west and east of New Guinea found that the first four PC axes explained 93% of the observed morphometric variation (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, S3, only PC axes 1 and 2 are shown). For Wallacea, PC axis 1 explains 74% of the variation and is positively correlated to all morphometric variables (i.e. body-size axis). PC axis 2 explains 10% and is positively correlated to mid-toe length and bill width but negatively correlated to tarsus length, tail length, wing length and bill length. For the Pacific, the first axis (PC1) explains 71% of the variation and is positively correlated to body size, whereas PC axis 2 explains 10% and is positively correlated to bill width and bill height but negatively correlated to tarsus length, mid-toe length and bill length.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Results from the PCA of morphological data from sympatric island taxa in Wallacea (n = 135) and the Pacific (n = 128) (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3), pruned to only include islands for which colonization was well separated in time with a putative late stage taxon-cycle taxon (filled symbols) and a more recent colonizer (open symbol). Identical colours indicate that taxa occur sympatrically. PC axes 1 and 2 are based on the covariance matrix of the log transformed morphological variables and explain 85% of the variation in Wallacea and 81% of the variation in the Pacific. Indicated to the right of each island name is the p-value of morphological separation among taxa within islands, following the permutational MANOVA tests.

Sympatric island taxa are in most cases clearly separated in morphospace (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, S3). In Wallacea, this is particularly apparent not only for sympatric taxa on Sumbawa (p < 0.001), Flores (p < 0.001), Timor (p < 0.001) and Wetar (p < 0.001), for which the time gap between first and second colonizations is the largest, but also for all other sympatric island taxa (p < 0.001). In the Pacific, the pattern is similar with sympatric taxa occupying distinct morphospace (p = 0.002–0.046). We also investigated the morphospace occupied by P. citreogaster on the larger Bismarck islands and the Pachycephala melanura that occurs on tiny islands in the same archipelago. These taxa appear never to co-occur and while this remarkable distributional pattern recently received some attention [28], we demonstrate that P. citreogaster and P. melanura are not separated in morphospace (p = 0.28).

(e). Testing for an association between old relictual taxa and larger islands

A total of 57 Pachycephala taxa were included in the null model-based tests of association between old relictual taxa and larger islands. Old relictual taxa showed a significant tendency to occupy larger islands (based on either island area or island elevation), with significant results for tests comparing the taxa with root distances of 3, 4 and 5 with the remaining taxa (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S3 and S4).

4. Discussion

(a). Ancestral area analyses, colonization directionality and detecting taxon cycles

The biogeographic analysis suggests that the origin of Pachycephala is Australo-Papuan. The origin of clades A–F is unequivocally found to be Melanesian leading to colonization of large parts of the Pacific archipelagos (figure 1, clades C–F), and then onwards to Australo-Papua (figure 1, clade A) and the Moluccas (figure 1, clade B). The interpretation would then be that Australo-Papua and the Moluccas was the result of back-colonization from the Pacific [50]. However, several phylogenetic relationships among these Pacific clades are poorly supported (see also [29]) obscuring the biogeographic colonization pattern.

The densely sampled molecular phylogeny demonstrates that members of the Pachycephala have independently colonized the Moluccas, the Lesser Sundas and the Pacific multiple times. Recent dispersal events have led to the colonization of the vast majority of islands in each region and for the expansions, which took place on recent time scales, extinctions may not yet have distorted the biogeographic pattern. Therefore, we may assume that historically, members of the Pachycephala possessed great colonization abilities and that the old monotypic lineages represent relictual forms that were once more widespread (table 1). The alternative explanation for the origin of the monotypic endemic lineages is that they arrived by long-distance dispersal. However, evidence from the recent insular colonizations within the Pachycephala suggests that colonization takes place sequentially across archipelagos and there are no examples of recent long-distance dispersal events from the Pachycephala phylogeny.

(b). Taxon cycles revisited

Taxon cycle predictions fall into three main categories pertaining to: (i) the age of lineages, the number of taxa in old and young lineages, and the geographical distribution of taxa in old and young lineages; (ii) the attributes of the islands that hold stage IV taxa; and (iii) the habitat, altitude and morphospace occupied by sympatric taxa, which serve as proxies for ecological adaptations [15,22]. We use the molecular phylogeny of Pachycephala to test a number of predictions associated with taxon-cycle events in the archipelagos surrounding Australo-Papua.

(i). Age, number of taxa and distribution of lineages

Taxon-cycle theory predicts that recent colonizers occur on all islands in a particular region (archipelago) and that they are represented by genetically closely related populations. These recent widespread colonizers may be genetically and morphologically similar (stage I), or well differentiated on each major island (stage II). On the other hand, taxa in stage IV of the taxon cycle represent old lineages that only survive as relictual populations on a few disjunct (or even on single) islands.

Investigating the number of lineages present halfway during the evolution of contemporary Pachycephala species reveals the presence of 11 lineages (figure 1). These 11 lineages represent three lineages with a high number of species and subspecies, namely: (i) clades A–F, excluding P. c. rosseliana/collaris, (ii) clade G, excluding P. m. calliope, and (iii) clade H as well as eight lineages with a limited number of taxa (table 1). Within the three taxon-rich lineages, we find 63 out of 66 subspecies of P. pectoralis s.l. and Pachycephala melanura. These have colonized all islands in certain archipelagos reflecting expansions over the north Moluccas (clade B), the Pacific archipelagos (clades C–F) and the Lesser Sundas (clade G). Each of these colonizations has then been followed by island-specific differentiation leading to a multitude of island-specific taxa in accord with the predictions of taxon-cycle expansion stages I and II.

Of the eight old lineages (table 1), five lineages are endemic to: (i) two islands in the Louisiade archipelago, (ii) Timor, (iii) New Caledonia, (iv) two islands in the Solomons, and (v) two islands in the western Lesser Sundas. These five taxon-poor lineages represent relictual taxa consistent with late stage taxon cycles. Finally, three of the eight old lineages are endemic to Australia and the highlands of New Guinea. Interpreting taxon-cycle patterns for the latter three lineages on more complex continental scales is difficult, but the two New Guinean lineages align with the expectations of late stage taxon-cycle events by inhabiting primary highland forest above 1000 m.a.s.l.

(ii). Size and altitude of islands that hold stage IV taxa

Population ecology theory predicts that small populations are more likely to go extinct than are large populations. Therefore, taxa on small islands are more prone to go extinct than that on large islands [5,51]. While correlated with island size, elevation may be important for persistence. High islands may be able to hold more species than low islands because of the greater variety of habitats available. Consequently, the taxon-cycle hypothesis predicts that relictual stage IV taxa occur on large and mountainous islands [21,22]. Six islands (three in the Pacific and three in Wallacea) representing some of the largest and/or highest islands in the region are inhabited by four out of five relictual lineages (table 1), along with another Pachycephala species (table 2), consistent with the taxon-cycle hypothesis (stage IV taxa). The last of the five relictual island lineages (P. c. rosseliana/collaris) inhabits two small islands southeast of New Guinea and falls outside the taxon-cycle predictions. These results are further corroborated by our null-models tests, which demonstrate a significant correlation between root distance and island size and island elevation (see the electronic supplementary material, tables S3 and S4).

(iii). Ecological adaptations (habitat, altitude and morphospace) of sympatric taxa

The taxon-cycle hypothesis predicts that young taxa in the expansion phases (stages I and II) are generalists, well suited for dispersal and colonization of new land, that occur at low altitudes often in coastal habitat, as mangrove. Over time, taxa evolve to become more specialized, moving away from coastal forest and mangrove and into primary forest habitat often at high altitudes (stages III and IV). Such adaptations may be reflected in morphological traits associated with diet, substrate use and movements [42,43]. We therefore expect to find morphological differentiation among sympatric island taxa, including relatively longer wings and shorter toes/tarsi in stages I and II taxa than in relictual lineages [26].

While we do find a tendency for relictual taxa to occupy inland primary montane habitats (five out of eight lineages, table 1), the ultimate comparison should be undertaken between sympatric island taxa. For the six islands that hold two Pachycephala taxa, for which relative phylogenetic position suggests a particular order of colonization, we find that the first colonizer occupies higher elevations and well-matured habitats (table 2). Some variation in the amount of overlap in habitat and elevation between sympatric island taxa is apparent. However, analyses of the morphospace occupied by co-occurring island taxa reveal that all sympatric island taxa are significantly separated in morphospace and no apparent correlation between size and shape is apparent for old relictial taxa relative to more recent colonizers (figure 2).

5. Conclusion

The idea that taxa pass through phases of expansions and contractions goes well back in time [52,53] but a more explicitly formulated taxon-cycle concept was developed by Wilson [14,15], Greenslade [16–18] and Ricklefs [21]. This study uses a densely sampled molecular subspecies phylogeny of a large monophyletic group to provide several lines of evidence supporting the idea that the contemporary diversity and distribution was shaped by cycles of expansions and contractions (taxon cycles): (i) recent colonizers representing stages I and II in the taxon cycle are widely distributed on both large and small islands across archipelagos, (ii) old relictual taxa are present on only the largest and highest islands, and (iii) when taxa in expanding stages (stages I and II) co-occur with taxa in the final contracting stage (IV) these taxa are segregated such that stage IV taxa occur at higher elevations and generally in undisturbed habitat, whereas stage I and II taxa occur at lower elevations in more disturbed (edge) habitat. Analyses of the morphological space occupied by sympatric island taxa show significant segregation. Consequently, our study provides new evidence independent of the existing work that supports the concept of taxon cycles in shaping the distribution of insular taxa.

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Rosindell, R. E. Ricklefs and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank the following institutions for providing tissue and/or footpad samples for this study: Australian Museum, Sydney, Australia (Walter Boles); American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA (Paul Sweet); Australian National Wildlife Collection, Canberra, Australia (Leo Joseph); British Museum of Natural History, Tring, UK (Robert Prys-Jones, Hein van Grouw and Mark Adams); Department of Zoology, University of Gothenburg (Urban Olsson); Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA (David Willard); Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Australia (Joanna Sumner); Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden (Ulf Johansson); Zoological Museum, Berlin Museum für Naturkunde, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany (Pascal Eckhoff and Sylke Frahnert); Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Denmark (Jan Bolding Kristensen); Western Australian Museum, Perth, Australia.

This study meets the terms of the ethics committees at the Natural History Museum London, and Imperial College London.

Funding statement

Fieldwork in the Moluccas was supported by a National Geographic Research and Exploration grant (no. 8853-10) and we are grateful to a number of Indonesian institutions that facilitated our fieldwork: the State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK), the Ministry of Forestry, Republic of Indonesia, the Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (RCB-LIPI) and the Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense (MZB). From the MZB, we are particular indebted to Tri Haryoko, Mohammed Irham and Sri Sulandari. S.M.C. acknowledges support from NERC for funding work in southern Melanesia. B.G.H. was supported by Imperial College London's Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and the Environment Initiative. K.A.J. and J.F. acknowledge the Danish National Research Foundation for funding to the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate. K.A.J. further acknowledges support from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement no. PIEF-GA-2011-300924.

References

- 1.Darwin C. 1859. On the origin of species by means of natural selection. London, UK: Murray [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace AR. 1876. The geographical distribution of animals. New York, NY: Harper [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayr E. 1942. Systematics and the origin of species. New York, NY: Columbia University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayr E. 1965. Avifauna: turnover on islands. Science 150, 1587–1588 (doi:10.1126/science.150.3703.1587) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacArthur RH, Wilson EO. 1963. An equilibrium theory of insular zoogeography. Evolution 17, 373–387 (doi:10.2307/2407089) [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacArthur RH, Wilson EO. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Monographs in population Biology, vol. 1, pp. 1–203 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diamond JM. 1974. Colonization of exploded volcanic islands by birds: the supertramp strategy. Science 183, 803–806 (doi:10.1126/science.184.4138.803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond JM. 1977. Continental and insular speciation in Pacific island birds. Syst. Zool. 26, 263–268 (doi:10.2307/2412673) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson KP, Adler FR, Cherry JL. 2000. Genetic and phylogenetic consequences of island biogeography. Evolution 54, 387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whittaker RJ, Triantis KA, Ladle RJ. 2008. A general dynamic theory of oceanic island biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 35, 977–994 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01892.x) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X-Y, He F. 2009. Speciation and endemism under the model of island biogeography. Ecology 90, 39–45 (doi:10.1890/08-1520.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosindell J, Phillimore AB. 2011. A unified model of island biogeography sheds light on the zone of radiation. Ecol. Lett. 14, 552–560 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01617.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosindell J, Harmon LJ. 2013. A unified model of species immigration, extinction and abundance on islands. J. Biogeogr. 40, 1107–1118 (doi:10.1111/jbi.12064) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson EO. 1959. Adaptive shift and dispersal in a tropical ant fauna. Evolution 13, 122–144 (doi:10.2307/2405948) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson EO. 1961. The nature of the taxon cycle in the Melanesian ant fauna. Am. Nat. 95, 169–193 (doi:10.1086/282174) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenslade PJM. 1968. The distribution of some insects of the Solomon Islands. Proc. Linn. Soc. 179, 189–196 (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1968.tb00976.x) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenslade PJM. 1968. Island patterns in the Solomon Islands bird fauna. Evolution 22, 751–761 (doi:10.2307/2406901) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenslade PJM. 1969. Insect distribution patterns in the Solomon Islands. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 255, 271–284 (doi:10.1098/rstb.1969.0011) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricklefs RE, Cox GC. 1972. Taxon cycles in the West Indian avifauna. Am. Nat. 106, 195–219 (doi:10.1086/282762) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricklefs RE, Cox GW. 1978. Stage of taxon cycle, habitat distribution, and population density in the avifauna of the West Indies. Am. Nat. 112, 875–895 (doi:10.1086/283329) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricklefs RE. 1970. Stage of taxon cycle and distribution of birds on Jamaica, Greater Antilles. Evolution 24, 475–477 (doi:10.2307/2406820) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricklefs RE, Bermingham E. 2002. The concept of the taxon cycle in biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 11, 353–361 (doi:10.1046/j.1466-822x.2002.00300.x) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricklefs RE. 2011. A biogeographical perspective on ecological systems: some personal reflections. J. Biogeogr. 38, 2045–2056 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02520.x) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricklefs RE, Bermingham E. 1999. Taxon cycles in the Lesser Antillean avifauna. Ostrich 70, 49–59 (doi:10.1080/00306525.1999.9639749) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jønsson KA, Bowie RCK, Moyle RG, Christidis L, Norman JA, Benz BW, Fjeldså J. 2010. Historical biogeography of an Indo-Pacific passerine bird family (Pachycephalidae): different colonization patterns in the Indonesian and Melanesian archipelagos. J. Biogeogr. 37, 245–257 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02220.x) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jønsson KA, Fabre P-H, Ricklefs RE, Fjeldså J. 2011. Major global radiation of corvoid birds originated in the proto-Papuan archipelago. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2328–2333 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1018956108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickinson EC. 2003. The Howard and Moore complete checklist of the birds of the world, 3rd edn Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jønsson KA, Bowie RCK, Moyle RG, Christidis L, Filardi CE, Norman JA, Fjeldså J. 2008. Molecular phylogenetics and diversification within one of the most geographically variable bird species complexes (Pachycephala pectoralis/melanura). J. Avian Biol. 39, 473–478 (doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04486.x) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen MJ, Nyári ÁS, Mason I, Joseph L, Dumbacher JP, Filardi CE, Moyle RG. In press. Molecular systematics of the world's most polytypic bird: the Pachycephala pectoralis/melanura (Aves: Pachycephalidae) species complex. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. (doi:10.1111/zoj.12088) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posada D, Crandall KA. 1998. Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14, 817–818 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwickl DJ. 2006. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analyis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. PhD dissertation, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. 2003. MrBayes: a program for the Bayesian inference of phylogeny, v. 3.1.2 See http://mrbayes.scs.fsu.edu/index.php

- 33.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973 (doi:10.1093/molbev/mss075) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drummond AJ, Ho SYW, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. 2006. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 4, e88 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. 2007. TRACER v1.4 See http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer

- 37.Nylander JAA, Wilgenbusch JC, Warren DL, Swofford DL. 2008. AWTY (are we there yet): a system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 24, 581–583 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm388) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ree RH, Moore BR, Webb CO, Donoghue MJ. 2005. A likelihood framework for inferring the evolution of geographic range on phylogenetic trees. Evolution 59, 2299–2311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ree RH, Smith SA. 2008. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst. Biol. 57, 4–14 (doi:10.1080/10635150701883881) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schellart WP, Lister GS, Toy VG. 2006. A Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic reconstruction of the Southwest Pacific region: tectonics controlled by subduction and slab rollback processes. Earth Sci. Rev. 76, 191–233 (doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2006.01.002) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall R. 2002. Cenozoic geological and plate tectonic evolution of SE Asia and the SW Pacific: computer based reconstructions, model and animations. J. Asian Earth Sci. 20, 353–431 (doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(01)00069-4) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricklefs RE, Travis J. 1980. A morphological approach to the study of avian community organization. Auk 97, 321–338 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miles DB, Ricklefs RE, Travis J. 1987. Concordance of eco-morphological relationships in three assemblages of passerine birds. Am. Nat. 129, 347–364 (doi:10.1086/284641) [Google Scholar]

- 44.R Development Core Team 2013. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson MJ. 2001. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 26, 32–46 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oksanen J, et al. 2012. vegan: community ecology package See http://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan

- 47.Boles WE. 2007. Family Pachycephalidae (whistlers). In Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 12 (eds del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie DA.), pp. 374–437 Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jombart T, Dray S. 2010. adephylo: exploratory analyses for the phylogenetic comparative method. Bioinformatics 26, 1907–1909 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq292) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Filardi CE, Moyle RG. 2005. Single origin of a pan-Pacific bird group and upstream colonization of Australasia. Nature 438, 216–219 (doi:10.1038/nature04057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pimm SL, Jones HL, Diamond J. 1988. On the risk of extinction. Am. Nat. 132, 757–785 (doi:10.1086/284889) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willis JC. 1922. Age and area: a study in geographical distribution and origin in species. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darlington PJ., Jr 1957. Zoogeography: the geographical distribution of animals. New York, NY: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galbraith ICJ. 1956. Variation, relationships and evolution in the Pachycephala pectoralis superspecies (Aves, Muscicapidae). Bull. Brit. Mus. Nat. Hist. 4, 131–222 [Google Scholar]