Abstract

TLR activation of innate immunity prevents the induction of transplantation tolerance and shortens skin allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade. The mechanism by which TLR signaling mediates this effect has not been clear. We now report that administration of the TLR agonists LPS (TLR4) or polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (TLR3) to mice treated with costimulation blockade prevents alloreactive CD8+ T cell deletion, primes alloreactive CTLs, and shortens allograft survival. The TLR4- and MyD88-dependent pathways are required for LPS to shorten allograft survival, whereas polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid mediates its effects through a TLR3-independent pathway. These effects are all mediated by signaling through the type 1 IFN (IFN-αβ) receptor. Administration of IFN-β recapitulates the detrimental effects of TLR agonists on transplantation tolerance. We conclude that the type 1 IFN generated as part of an innate immune response to TLR activation can in turn activate adaptive immune responses that abrogate transplantation tolerance. Blocking of type 1 IFN-dependent pathways in patients may improve allograft survival in the presence of exogenous TLR ligands.

Toll-like receptors are a family of evolutionarily conserved proteins that activate innate immunity through the recognition of exogenous infectious agents and endogenous adjuvants (1). The innate immune responses to TLR activation are important modulators of adaptive immune responses (2). Exogenous TLR ligands include microbial components such as bacterial LPS and viral dsRNA (1). Endogenous TLR ligands generated in the course of tissue injury and cell death include heat shock proteins, heparin sulfate, and hyaluronan (3). Levels of many of these endogenous TLR ligands increase during the transplantation procedure and their release from damaged tissues may lead to a process termed “sterile inflammation” (4).

TLR activation has been implicated in the loss of self-tolerance leading to autoimmunity (3, 5) and more recently found to be important in transplantation (6, 7). The role of TLRs in transplantation has gained increased attention as newer protocols are designed to supplant immunosuppression with tolerance induction (8). There is increasing concern that the safety and efficacy of these protocols could be compromised by TLR-induced inflammation (9–13).

One approach that has achieved transplantation tolerance in animal models is based on costimulation blockade (14, 15). We use a combination therapy consisting of a donor-specific transfusion (DST)4 and anti-CD154 mAb that, together, we refer to as co-stimulation blockade (16). This protocol prolongs skin, cardiac, and islet allograft survival in mice (12, 16, 17) and is efficacious in nonhuman primates (18, 19). In this protocol, anti-CD154 mAb blocks interaction between CD154 on alloreactive T cells and CD40 on APCs, effectively preventing T cell-induced APC maturation (16). This in turn leads to deletion of host alloreactive CD8+ T cells (20), a critical step for prolonging skin allograft survival (21, 22). TLR activation, however, provokes an inflamma-tory response, cytokine secretion, and APC maturation that is independent of the interaction between CD154 and CD40 (1). We have previously shown that TLR activation can bypass costimulation blockade, activate adaptive immunity, and impair allograft survival (13).

In the present study, we identified a central mechanism by which TLR activation of innate immunity cross-communicates with adaptive immunity and precipitates allograft rejection in mice treated with costimulation blockade. We observed that TLR activation induced type 1 IFN (IFN-αβ) and that signaling through the type 1 IFN receptor (IFN-RI) prevents the deletion of alloreactive CTLs that in turn mediate short allograft survival. These results suggest that the induction of IFN-αβ is a fundamental mechanism by which innate immunity engenders an adaptive immune response capable of abrogating transplantation tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 (H2b), CBA/J (H2k), and BALB/c (H2d) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories or The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/10ScSnJ (23) (H2b, abbreviated as TLR4+/+), C57BL/10ScNJ (H2b, Tlr4lps-el, abbreviated as TLR4–/–), and B6.129S1-Tlr3tm1Flv/J (H2b, abbreviated as B6.TLR3–/–) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and bred at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA). Mice deficient in Myd88 (24) and Ifnar1 (abbreviated as IFN-RI) (25) were the gift of Dr. E. Lien (University of Massachusetts Medical School. The B6.129/SvJ-Myd88tm1AK1 (N6, hereafter B6.MyD88–/–) mice were originally obtained from Dr. D. Golenbock (University of Massachusetts Medical School) and the B6.129S2-Ifnar1tm1At (N12, hereafter B6.IFN-RI–/–) mice from Dr. J. Sprent (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). (CBA/J × KB5.CBA)F1 CD8+ T cell TCR-transgenic mice were developed by Dr. A. Mellor (Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA) and bred in our animal facility. The TCR transgene is expressed in CBA (H2k) mice by CD8+ cells and has specificity for native H2-Kb (26). All animals were certified viral Ab free and maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Generation of CD8+ KB5 TCR-transgenic synchimeric CBA/J mice

CBA/J nontransgenic mice were treated with 200 cGy of whole-body gamma irradiation from a 137Cs source (Gammacell 40; Atomic Energy of Canada or Mark I-30 Series 2000 Ci; JL Shepherd & Associates) and given a single i.v. injection of 0.5 × 106 bone marrow cells from CBA.KB5 TCR-transgenic mice as described (26). To allow sufficient time for hemopoietic chimerism to develop, the KB5 synchimeric mice received co-stimulation blockade treatment at 12–18 wk of age, 8–14 wk after irradiation and injection of KB5-transgenic bone marrow (26).

Skin allograft transplantation

Recipient mice of the specified strain were treated with a DST, anti-CD154 mAb, and given skin allografts as described previously (17). Briefly, a DST, consisting of 107 splenocytes from BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice, was injected i.v. on day –7 relative to the day of skin transplantation on day 0. Mice were then injected i.p. with anti-CD154 mAb (0.5 mg/dose) on days –7, –4, 0, and +4. TLR agonists were injected i.p. on day –7, the day of DST treatment. Full-thickness skin grafts 1–2 cm in diameter were obtained from the flanks of donor mice and transplanted onto the dorsal flanks of recipients on day 0 (17). Graft rejection was defined as the first day on which the entire graft was necrotic (17). Purified hamster anti-mouse CD154 mAb (clone MR1) was obtained from the National Cell Culture Center (Minneapolis, MN). The concentration of contaminating endotoxin was determined by a commercial firm (Charles River Endosafe) and was uniformly <10 endotoxin units per mg of mAb (13).

Islet allograft transplantation

Recipient mice 6–12 wk of age were rendered hyperglycemic by a single i.p. injection of streptozotocin (150 mg/kg). Diabetes was defined as a plasma glucose concentration of >250 mg/dl on two successive tests on different days. Plasma glucose concentration was measured using an Accu-Chek Active meter (Roche Diagnostics). All diabetic animals were treated with s.c. insulin pellets (Linbits; Linshin) that were removed at the time of islet transplantation. Mice were treated with DST and anti-CD154 mAb as described for skin allograft transplantation. Groups treated with anti-CD154 mAb without DST received four doses of the mAb on the usual schedule relative to transplantation. Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion (16) and transplanted at a dose of 20 per g body weight into the renal subcapsular space of chemically diabetic recipients. Grafts that did not reduce blood glucose concentration to <250 mg/dl within 48 h were deemed technical failures and were excluded from analysis. Mice were monitored for glycosuria two to three times weekly (Clinistix; Bayer). Blood glucose concentration was measured in all glycosuric animals. Graft rejection was defined as recurrence of a blood glucose concentration >250 mg/dl on 2 successive days. In the case of islet recipients that were normoglycemic at the end of the observation period, graft function was confirmed by unilateral nephrectomy of the kidney bearing the transplant and documentation of the reappearance of diabetes.

Preparation and injection of TLR agonists

Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C); Sigma-Aldrich or GE Health-care) was dissolved in Dulbecco's PBS (D-PBS) at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Stock was stored at –20°C until needed. LPS from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich) was repurified as previously described (13), except that phenol-PBS phase separation was conducted at 2000 × g for 30 min to accommodate larger volumes. Repurified LPS was suspended in D-PBS with an assumed 10% loss during repurification (13). Repurified LPS was stored at 4°C until used. Recombinant mouse IFN-β was obtained from R&D Systems).

We determined previously that 50 μg of poly(I:C) is an optimal dose for shortening skin allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade (13). To determine an optimal dose for LPS to use in our experiments, we performed a preliminary dose titration experiment. C57BL/6 mice were treated with costimulation blockade as described in Skin allograft transplantation. Separate cohorts of mice were also given 100 μg (mean survival time (MST) = 9.5 days, n = 4), 50 μg (MST = 9 days, n = 3), 25 μg (MST = 16 days, n = 4), 10 μg (MST = 22 days, n = 4) or no LPS (MST = 63 days, n = 3). Based on these data, all subsequent experiments were performed using 100 μg of LPS and 50 μg of poly(I:C).

Flow microfluorometry and Abs

A mouse hybridoma cell line secreting the KB5-specific clonotypic mAb Desiré (DES) (27) was a gift from Dr. J. Iacomini (Harvard Medical School). FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2a developing reagent for DES (clone R19-15), anti-mouse CD8α-PerCP (clone 53-6.7), and purified anti-mouse CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2) mAbs were obtained from BD Pharmingen. Isotype control mAbs were also obtained from BD Pharmingen.

Heparinized whole blood was washed in D-PBS containing 1% fetal clone serum (HyClone) and 0.05% sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated in anti-CD16/32 for 5 min at 4°C before incubation for 20 min with the clonotypic DES mAb. They were washed and incubated for 20 min with fluorescently labeled Abs to mouse CD8α and the secondary development Ab for DES. Samples were processed with FACS lysing solution (BD Biosciences) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Labeled cells were washed, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences) in D-PBS, and analyzed with a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star). Lymphoid cells were gated according to their light-scattering properties.

IFN-αβ bioassay

IFN-αβ was measured using a standard virus inhibition bioassay (28). Whole blood was obtained from mice 16 h after costimulation blockade treatment and centrifuged to obtain serum, which was diluted 2-fold across a 96-well plate. Each well was seeded with 3 × 104 mouse L-929 cells (NCTC clone 929; American Type Culture Collection) and incubated overnight. In brief, 2 × 105 PFUs of vesicular stomatits virus strain Indiana was then added to each well, except for the uninfected control wells. Cultures were observed by microscopy for cytopathic effects (CPE) 2 days later. The IFN-αβ titer was determined as the reciprocal of the dilution that provided 50% protection from CPE (28).

In vivo cytotoxicity assay

The in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed as described elsewhere (29). Briefly, single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens that were obtained from C57BL/6 (H2b, syngeneic) or BALB/c (H2d, allogeneic) mice. Cells were washed with HBSS (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and each population was incubated in either 2.5 or 0.625 μM CFSE (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for 15 min at 37°C. Splenocytes were washed with HBSS and combined at equal ratios. A total of 3 × 107 cells was adoptively transferred i.v. into recipient mice that had been treated with 0.025 mg of a depleting anti-NK1.1 mAb 24–48 h earlier to deplete NK cell activity. All cytotoxicity observed in this assay in NK cell-depleted mice is due to CD8 CTLs (30). Spleens from recipient mice were harvested 4 h after the transfer and lysed with FACS lysing solution (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were analyzed with a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star). Specific lysis was calculated by comparing the relative survival of each target population to the survival in NK cell-depleted naive mice using the following equation, the derivation of which was described previously (30): 100 – (((percentage of target population in experimental/percentage of syngeneic population in experimental)/(percentage of target population in NK1.1-depleted naive/percent syngeneic population in NK1.1-depleted naive)) × 100).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software. Three or more means were compared by one-way ANOVA and the Bonferroni multiple comparison test. Allograft survival curves were generated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank statistic. Duration of allograft survival is presented as the median. Values of p < 0.05 are considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

LPS shortens skin allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade through a MyD88-dependent mechanism

LPS shortens skin allograft survival in mice treated with co-stimulation blockade (13). Because TLR4 signals through both MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways (1), we first asked whether the ability of LPS to shorten allograft survival required MyD88.

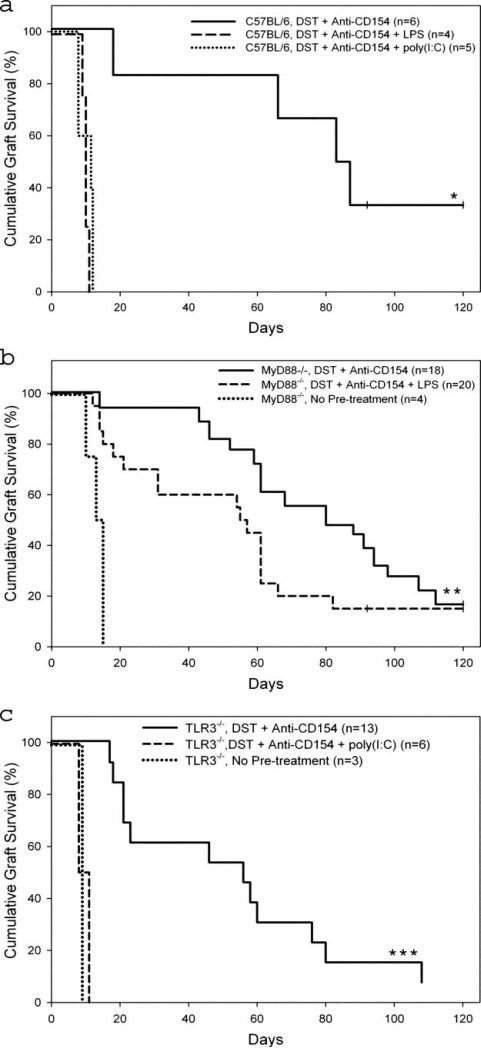

C57BL/6 and B6.MyD88–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade and transplanted with BALB/c skin allografts exhibited prolonged allograft survival, achieving comparable MST of 85 days (Fig. 1a) and 84 days (Fig. 1b), respectively. LPS administration at the time of tolerance induction failed to shorten skin allograft survival in B6.MyD88–/– mice (MST = 56 days; Fig. 1b), whereas it did so consistently in C57BL/6 mice (MST = 9.5 days; Fig. 1a). As previously reported (31), untreated B6.MyD88–/– mice rapidly rejected fully MHC-mismatched skin allografts (MST = 14 days; Fig. 1b). These data demonstrate that LPS requires the MyD88-dependent pathway to shorten skin allo-graft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade.

FIGURE 1.

LPS acts through the MyD88-dependent TLR4 pathway and poly(I:C) acts independently of TLR3 to shorten costimulation blockade-induced skin allograft survival. C57BL/6 (a), B6.MyD88–/– (b), or B6.TLR3–/– (c) mice were treated with our standard costimulation blockade protocol, a single injection of BALB/c DST on day –7 followed by four injections of anti-CD154 mAb on days –7, –4, 0, and +4 relative to transplantation with a BALB/c skin allograft on day 0. Animals were coinjected i.p. with LPS or poly(I:C) on day –7 as indicated. Untreated animals received a BALB/c skin allograft with no preconditioning. *, Duration of graft survival in C57BL/6 mice treated with costimulation blockade was statistically significantly longer than in mice treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS or poly(I:C), p < 0.01. **, Duration of graft survival was not statistically different between B6.MyD88–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade or costimulation blockade plus LPS (p = 0.095). B6.MyD88–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade or costimulation blockade plus LPS exhibited prolonged graft survival compared with untreated B6.MyD88–/– mice (p < 0.001). ***, Duration of graft survival in B6.TLR3–/– groups treated with costimulation blockade and costimulation blockade plus poly(I:C) was statistically significantly different (p < 0.001).

Shortened skin allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade plus poly(I:C) is independent of TLR3 signaling

Administration of poly(I:C) at the time of costimulation blockade shortens skin allograft survival (13). Poly(I:C) signals through several different receptors, including TLR3 (32), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (33), melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (34), and protein kinase RNA (35). We next asked whether the ability of poly(I:C) to shorten allograft survival requires signaling through TLR3.

C57BL/6 and B6.TLR3–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade and transplanted with BALB/c skin allografts exhibited prolonged allograft survival with MSTs of 85 days (Fig. 1a) and 56 days (Fig. 1c), respectively ( p = NS). As expected (13), C57BL/6 mice treated with costimulation blockade plus poly(I:C) rapidly rejected skin allografts (MST = 10 days; Fig. 1a). Injection of poly(I:C) also shortened skin allograft survival in B6.TLR3–/– mice (MST = 10 days; Fig. 1c). These data show that signaling through TLR3 is not required for poly(I:C) to shorten skin allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade.

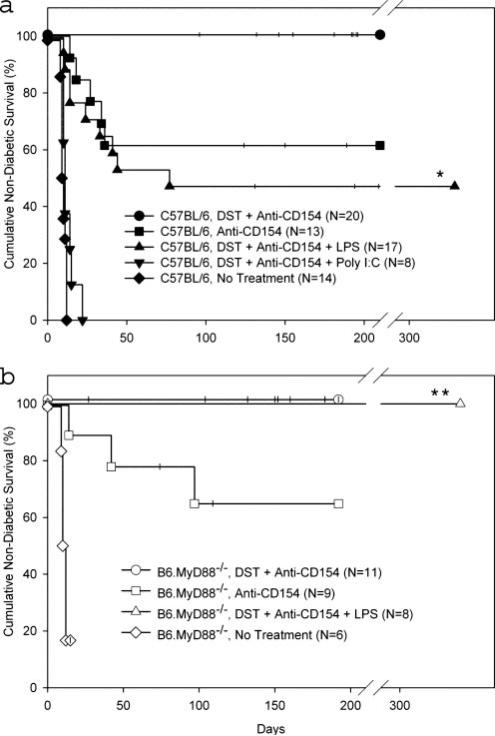

Poly(I:C) abrogates, whereas LPS only partially impairs, islet allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade

For reasons not completely understood, the efficacy of costimulation blockade for prolonging allograft survival in mice is tissue dependent; it is more effective for islet than for skin allografts. We therefore asked whether TLR agonists would shorten islet allograft survival to a degree comparable to that observed using the more rigorous skin allograft model. Chemically diabetic C57BL/6 mice were treated with costimulation blockade, with or without coin-jection of LPS or poly(I:C), and transplanted with BALB/c islet allografts.

Permanent islet allograft survival (>200 days) was achieved in all (20 of 20) C57BL/6 mice treated with costimulation blockade (Fig. 2a). Injection of poly(I:C) at the time of tolerance induction, however, led to rapid islet allograft rejection (MST = 11 days; Fig. 2a). In contrast, injection of LPS at the time of costimulation blockade, using a dose capable of completely abrogating skin allograft survival, shortened islet allograft survival only to an intermediate degree (MST = 77 days), with 47% (8 of 17) of islet allografts surviving >200 days (Fig. 2a). Duration of islet allograft survival in LPS-injected mice was similar to that observed in wild-type mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb monotherapy ( p = NS; Fig. 2a), a treatment known to achieve only minimal alloreactive CD8+ T cell deletion (26). These data document that both poly(I:C) and LPS have a detrimental effect on islet allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade. At the doses tested, the effect was more pronounced in recipients injected with poly(I:C).

FIGURE 2.

LPS shortens and poly(I:C) abrogates costimulation blockade-induced islet allograft survival. C57BL/6 (a) or B6.MyD88–/– (b) mice were given the indicated treatment on day –7 relative to transplantation with BALB/c islet allografts on day 0 as described in Materials and Methods. *, Duration of graft survival in the C57BL/6 group treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS was significantly different from that in groups treated with costimulation blockade (p < 0.001) or costimulation blockade plus poly(I:C) (p < 0.0001). **, Duration of graft survival in the B6.MyD88–/– group treated with costimulation blockade was not significantly different from survival in the group treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS.

We next determined whether LPS mediates its effects on islet allograft survival by signaling through the MyD88-dependent pathway as was the case for skin allograft survival (Fig. 1b). We first confirmed that untreated B6.MyD88–/– mice rapidly reject fully MHC-mismatched islet allografts (MST = 11 days) with a time course similar to that observed in C57BL/6 mice (MST = 9.5 days; Fig. 2). We next confirmed that costimulation blockade induced permanent islet allograft survival (>200 days) in all (11 of 11) B6.MyD88–/– mice (Fig. 2b). Consistent with our skin allo-graft observations (Fig. 1b), islet allograft survival was also permanent (>200 days) in all (8 of 8) B6.MyD88–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade and LPS (Fig. 2b).

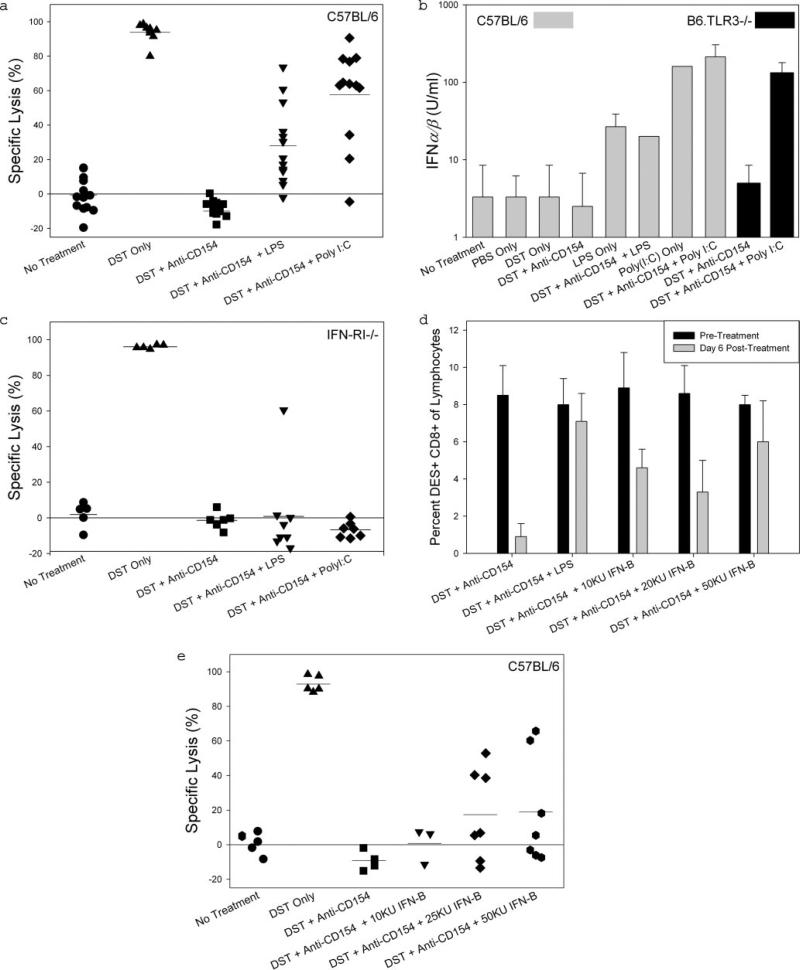

LPS and poly(I:C) prime allospecific effector cells in mice treated with costimulation blockade

Costimulation blockade prevents the priming of host alloreactive CD8+ T cells and the generation of effector/memory CTLs (13, 30). We hypothesized that LPS has a more modest effect than poly(I:C) on islet allograft survival because LPS leads to less efficient priming of alloreactive T cells in mice treated with costimulation blockade. To test this, C57BL/6 mice were treated with costimulation blockade. Then, on the scheduled day of transplantation, they were not given grafts but instead analyzed for their ability to rapidly kill allogeneic target cells using an in vivo cytotoxicity assay. In this assay, rapid clearance of allogeneic cells in NK cell-depleted mice is indicative of effector CTL activity (29).

Low levels of CTL activity were observed in mice treated with costimulation blockade, whereas mice treated with only DST (to prime CTLs) exhibited strong cytotoxic activity (Fig. 3a). Mice treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS exhibited in vivo cytotoxicity activity that was ~2-fold lower than that observed in mice treated with poly(I:C) (Fig. 3a). These data show that, at these doses, poly(I:C) is more effective than LPS in priming allospecific CTL activity in mice treated with costimulation blockade.

FIGURE 3.

IFN-αβ is necessary and sufficient for alloreactive CD8+ T cell priming in mice treated with costimulation blockade. a, C57BL/6 mice depleted of NK cells were given the indicated treatment on day –7 relative to receiving an adoptive transfer containing a 50:50 mixture of syngeneic (C57BL/6) and allogeneic (BALB/c) splenocytes that were labeled with different concentrations of CFSE, also referred to as an in vivo cytotoxicity assay. Groups treated with anti-CD154 mAb were given a second dose on day –4. The percent specific lysis was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. One-way ANOVA revealed an overall difference of p < 0.0001 among all groups. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test showed a statistical difference between the group treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS and the groups treated with costimulation blockade (p < 0.001) or costimulation blockade plus poly(I:C) (p < 0.001). b, Serum was collected from C57BL/6 or B6.TLR3–/– mice 16 h after receiving the indicated treatment. The IFN-αβ titer was determined as the reciprocal of the dilution that protected L-929 cells from CPE caused by vesicular stomatitis virus infection. n = 3 for all samples. The y-axis is log10 scale. c, An in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed in B6.IFN-RI–/– as described for a. One-way ANOVA revealed an overall difference of p < 0.0001 among all groups. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test showed no statistical difference between the group treated with costimulation blockade and the groups treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS (p = NS) or costimulation blockade plus poly(I:C) (p = NS). d, KB5 synchimeric mice were treated with DST and anti-CD154 mAb, with or without i.p. coinjection of LPS or IFN-β, on day –7 and injected with anti-CD154 mAb on day –4 relative to quantifying levels of TCR-transgenic DES+CD8+ alloreactive T cells in the blood on day –1, the day before allograft transplantation in our costimulation blockade protocol. Chimerism in the peripheral blood was determined by flow cytometry analysis of the percentage of DES+CD8+ cells. e, An in vivo cytotoxicity assay was performed in C57BL/6 mice as described in a. IFN-β was administered by i.p. injection at the time of treatment with DST and anti-CD154 mAb. The dose of IFN-β is expressed in kilounits (KU) (28). One-way ANOVA revealed an overall difference of p < 0.0001 among all groups. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test showed a statistical difference between the group treated with costimulation blockade and the groups treated with costimulation blockade plus 25 KU of IFN-β (p < 0.05) or costimulation blockade plus 50 KU of IFN-β (p < 0.05), but not the group treated with costimulation blockade plus 10 KU IFN-β (p = NS).

IFN-αβ is necessary to prime allospecific CTLs

We next sought to identify the mechanism by which LPS and poly(I:C) shorten allograft survival. We tested the hypothesis that IFN-αβ, a potent immunomodulator of CD8+ T cells, was responsible. To do so, we first quantified circulating IFN-αβ levels in mice treated with costimulation blockade plus LPS or poly(I:C) using a standard bioassay (28).

We detected minimal IFN-αβ (≤10 U/ml) in untreated mice, or mice treated with PBS, DST alone, or costimulation blockade 16 h earlier (Fig. 3b). LPS induced moderate levels of IFN-αβ, whereas poly(I:C) induced high levels of IFN-αβ, irrespective of treatment with costimulation blockade (Fig. 3b). Levels of IFN-αβ induced by poly(I:C) were similar in B6.TLR3–/– and C57BL/6 mice treated with costimulation blockade (Fig. 3b). These data demonstrate that poly(I:C) induces levels of IFN-αβ higher than those induced by LPS and does so through a TLR3-independent mechanism.

To determine whether IFN-αβ induced by LPS and poly(I:C) is the mechanism by which TLR ligands lead to the development of primed allospecific CTLs, we repeated the in vivo cytotoxicity assay using B6.IFN-RI–/– mice, which are incapable of signaling in response to IFN-αβ (25). B6.IFN-RI–/– mice treated with co-stimulation blockade exhibited negligible CTL activity, whereas B6.IFN-RI–/– mice primed by injection of DST exhibited robust CTL activity (Fig. 3c). B6.IFN-RI–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade plus either LPS or poly(I:C) exhibited essentially undetectable CTL activity (Fig. 3c). These data demonstrate that signaling through IFN-RI is necessary for both LPS and poly(I:C) to induce primed allospecific CTLs in mice treated with costimulation blockade.

IFN-β is sufficient to impair deletion and promote priming of alloreactive CD8+ T cells

We next asked whether injection of IFN-β would recapitulate the effects of TLR agonists on tolerance induction. To determine this, we generated mice that circulate a tracer population of transgenic alloreactive CD8+ T cells that recognize H2-Kb (26) (KB5 synchimeric mice). Consistent with previous reports (26), KB5 synchimeric mice treated with costimulation blockade subsequently exhibited a dramatic reduction (90 ± 7% deletion) in the percentage of alloreactive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3d). We have previously demonstrated that this deletion occurs through an apoptotic mechanism that results from aborted activation (13, 26). As expected (13), i.p. injection of LPS at the time of treatment with DST and anti-CD154 mAb significantly prevented deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells (10 ± 20%; Fig. 3d). Interestingly, a single i.p. injection of IFN-β partially prevented deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells at a dose of either 1 × 104 U (47 ± 11%) or 2 × 104 U (63 ± 15%) and substantially reduced it (24 ± 31%) at a dose of 5 × 104 U (Fig. 3d).

We next determined whether the increasing doses of IFN-β that prevented alloreactive CD8+ T cell deletion would also lead to increasing allospecific CTL activity. Intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 104 U of IFN-β at the time of treatment with DST and anti-CD154 mAb did not induce CTL activity in mice treated with costimulation blockade, whereas injection of 2.5 × 104 or 5 × 104 U of IFN-β led to substantial CTL activity (Fig. 3e). Together, these data demonstrate that IFN-β is sufficient to prevent the deletion and to promote the priming of alloreactive CD8+ CTLs in mice treated with costimulation blockade.

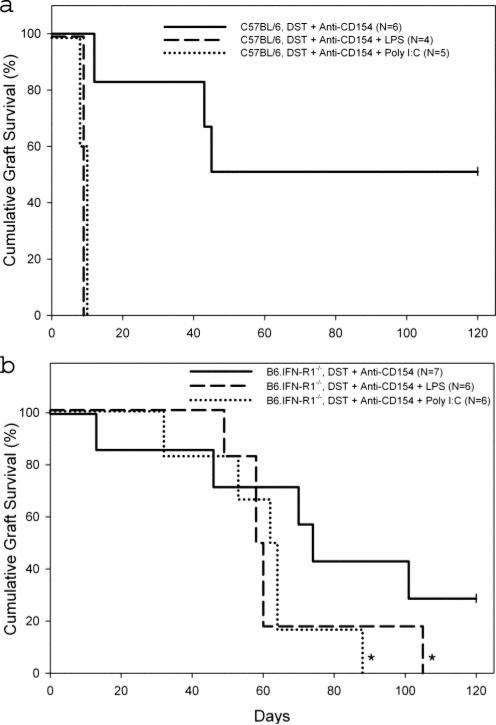

LPS and poly(I:C) shorten skin allograft survival by inducing IFN-αβ

To demonstrate directly that LPS and poly(I:C) shorten allo-graft survival through an IFN-αβ-dependent mechanism, we tested the effects of these TLR agonists on skin allograft survival in C57BL/6 and B6.IFN-RI–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade. Costimulation blockade prolonged skin allo-graft survival in C57BL/6 (MST > 85 days; Fig. 4a) and B6.IFN-RI–/– (MST = 72 days; Fig. 4b) mice. As expected (Fig. 1a), costimulation blockade-treated C57BL/6 mice given LPS (MST = 10 days) or poly(I:C) (MST = 10 days) rapidly rejected skin allografts (Fig. 4a). Strikingly, neither LPS (MST = 59 days) nor poly(I:C) (MST = 63 days) significantly shortened skin allograft survival in B6.IFN-RI–/– mice ( p = NS; Fig. 4b). These data document that LPS and poly(I:C) shorten skin allograft survival by inducing IFN-αβ that signals through the IFN-RI receptor.

FIGURE 4.

IFN-αβ is essential for LPS and poly(I:C) to abrogate skin allograft survival prolonged by costimulation blockade. C57BL/6 (a) or B6.IFN-RI–/– (b) mice were given the indicated treatment according to our standard protocol as described in Fig. 1. *, p = NS vs IFN-RI–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade alone.

LPS impairs alloreactive CD8+ T cell deletion regardless of donor TLR4 and CD80/86 expression

In a final series of studies, we investigated whether LPS activation of the DST contributed to the deleterious effects of TLR ligation on costimulation blockade. We first asked whether TLR4 expression on DST is required for LPS to prevent the deletion of host CD8+ T cells that recognize alloantigen directly. Using KB5 synchimeric mice treated with either TLR4+/+ or TLR4–/– C57BL/6 DST plus anti-CD154 mAb, we observed robust deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells (Table I, groups 1 and 3). Administration of LPS impaired this deletional activity regardless of whether or not TLR4 was expressed on the DST (Table I, groups 2 and 4). These data indicate that TLR4 on the DST is not required to prevent alloreactive CD8+ T cell deletion in mice treated with costimulation blockade and LPS.

Table I.

Neither TLR4 nor CD80/CD86 are required on DST for LPS to prevent CD8+ T cell deletiona

| Group | Anti-CD154 mAb | DST | LPS | KB5 CD8+ T Cells Pretreatment (%) | KB5 CD8+ T Cells 6 Days Posttreatment (%) | n | Deletion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | TLR4+/+ | No | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4 | 93.6 ± 3.8 |

| 2 | Yes | TLR4+/+ | Yes | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 4 | 13.0 ± 14.0b |

| 3 | Yes | TLR4−/− | No | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4 | 93.3 ± 0.03 |

| 4 | Yes | TLR4−/− | Yes | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 4 | –0.06 ± 0.27c |

| 5 | Yes | C57BL/6 | No | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 4 | 84.5 ± 10.8 |

| 6 | Yes | C57BL/6 | Yes | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 4 | –36.2 ± 12.9d |

| 7 | Yes | CD80/86−/− | No | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 4 | 86.0 ± 9.63 |

| 8 | Yes | CD80/86−/− | Yes | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 4 | –15.6 ± 34.6e |

KB5 synchimeric mice were treated with DST, anti-CD154 mAb, and LPS as indicated on day –7 and anti-CD154 mAb on day –4 relative to the day of allograft transplantation in our costimulation blockade protocol. Circulating levels of TCR-transgenic DES+CD8+ alloreactive T cells in the blood were quantified before treatment and on day –1 by flow cytometry. Data are shown as arithmetic means ± SD. One-way ANOVA revealed overall statistical significance among groups 1–4 (F3,12 = 47, p < 0.0001) and among groups 5–8 (F3,12 = 43, p < 0.0001).

p < 0.001 vs group 1.

p < 0.001 vs group 3; p = NS vs group 2.

p < 0.001 vs group 5.

p < 0.001 vs group 7; p = NS vs group 6.

We then asked whether IFN-αβ induced by LPS might up-regulate costimulatory molecules on APCs in the DST. In theory this could bypass costimulation blockade and directly co-stimulate host alloreactive CD8+ T cells, rescuing them from apoptosis. To exclude this possibility, KB5 synchimeric mice were treated with anti-CD154 mAb plus DST obtained from normal or CD80/CD86 knockout C57BL/6 mice. Synchimeric mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb and wild-type DST exhibited robust deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells that was prevented by LPS (Table I, groups 5 and 6). LPS also impaired CD8+ T cell deletion when mice were injected with CD80/ CD86-deficient DST (Table I, groups 7 and 8), demonstrating that up-regulation of these costimulatory molecules on the DST is not responsible for the effect of LPS on CD8+ alloreactive T cell deletion.

Discussion

Innate immune activation by TLR agonists shortens allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In a previous report (13), we demonstrated that TLR agonists act directly on host tissue to prevent the deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells, which are indispensable for TLR-mediated allograft rejection. We provide evidence that the TLR4 agonist LPS and the viral dsRNA mimetic poly(I:C) shorten allograft survival by signaling through two different pathways, one that requires its cognate TLR and one that does not. Both signaling pathways converge to mediate their activities through a common mechanism, the induction of IFN-αβ and subsequent signaling through IFN-RI. These data suggest that a fundamental mechanism by which innate immunity modulates adaptive immune responses and transplantation tolerance is through pathways regulated by type 1 IFN.

We document a critical role for both TLR-dependent (LPS) and TLR-independent (poly(I:C)) mechanisms in inducing IFN-αβ and impairing tolerance induction, but other factors may be involved. IFN-αβ production in response to LPS is believed to be MyD88 independent (36). Therefore, it was interesting to discover that LPS shortens skin and islet allograft survival in a MyD88-dependent manner, suggesting that an unidentified mediator in addition to IFN-αβ might exist. This finding is consistent with work by other groups (12, 37), who demonstrated that LPS counteracts the effects of anti-CD154 mAb blockade through a MyD88-dependent mechanism. However, unlike these previous reports, we observed that MyD88-deficient animals do not exhibit improved allograft survival compared with wild-type animals when treated with co-stimulation blockade (DST plus anti-CD154 mAb) but no TLR agonist.

We most likely obtained different results due to the different tolerance induction protocols. Our costimulation blockade protocol is a combination therapy consisting of DST and anti-CD154 mAb and differs in efficacy and mechanism from anti-CD154 mAb monotherapy (12) or anti-CD154 mAb and CTLA4-Ig combination therapy (37). First, DST and anti-CD154 mAb cotreatment prolongs, whereas anti-CD154 mAb monotherapy (12) or anti-CD154 mAb and CTLA4-Ig cotreatment (37) fail to prolong skin allograft survival in wild-type animals. Second, DST and anti-CD154 mAb combination therapy leads to the deletion of allo-reactive CD8+ T cells, whereas anti-CD154 mAb monotherapy does not (26). We have previously shown that skin allograft rejection in mice treated with DST, anti-CD154 mAb, and LPS is CD8 dependent (13).

We have excluded the MyD88-dependent cytokines IL-12 and TNF-α as candidates for this mediator (13), but IL-6 remains an attractive candidate that we have not yet evaluated. IL-6 impairs regulatory T cell induction and promotes proinflammatory TH17 cell generation (38), and it is known that regulatory T cells are important in transplantation tolerance (17, 39, 40). It is possible that LPS suppresses the generation of regulatory T cells induced by costimulation blockade (17, 39, 40). This possibility is supported by the recent demonstration that TLR activation prevents intragraft recruitment of regulatory T cells in mice treated with costimulation blockade and given cardiac allografts (12). We speculate that LPS, a relatively poor inducer of IFN-αβ compared with poly(I:C), must synergize with a cytokine such as IL-6 (41) to shorten allograft survival. This speculation is supported by a recent report that showed that the number of IL-6-producing dendritic cells is diminished in MyD88-deficient recipients of allografts, even in the presence of anti-CD154 mAb monotherapy (37).

Our observation that signaling through TLR3 is dispensable for poly(I:C) to induce IFN-αβ and shorten skin allograft survival is not surprising. IFN-α production in response to poly(I:C) is more dependent on signaling through the dsRNA helicase melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 than through the Toll/IL-1R (TIR) domain-containing adaptor protein-inducing IFN-β, a key signaling component of the TLR3 pathway (42).

Given the differential potency of poly(I:C) and LPS as inducers of IFN-αβ, it was not surprising that we observed differences in their biological effects. These two agonists differed in the degrees to which they allowed in vivo development of functional CTLs and shortened islet allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade. The effects of LPS and poly(I:C) on CTL development and skin allograft survival required signaling through the IFN-RI receptor, documenting a critical role for IFN-αβ production. This cause-effect relationship was confirmed by demonstrating that increasing doses of IFN-β led to increased survival of alloreactive CD8+ T cells and increased CTL activity in mice treated with costimulation blockade.

In light of mounting evidence that different tissues vary in their susceptibility to T cell-mediated rejection (40, 43, 44), we hypothesized that differential induction of IFN-αβ by LPS and poly(I:C) would differentially affect islet and skin allograft survival. It was not surprising that LPS, which effectively prevents CD8+ T cell deletion but induces lower levels of CTL activity than does poly(I: C), shortens skin allograft survival to a greater degree than islet allograft survival. Skin allograft survival is highly dependent on CD8+ T cell deletion (26), whereas islet allograft survival is prolonged by anti-CD154 monotherapy which does not lead to deletion (26, 44).

Many studies have shown that IFN-αβ can be either inhibitory or stimulatory to T cell function and may act directly on T cells or indirectly on accessory cells. IFN-αβ can stimulate APC maturation and costimulatory molecule expression (45), but induces APC dysfunction at high concentrations (46). In our model, IFN-αβ does not impair the deletion of the naive allospecific CD8+ T cells by up-regulating CD80 and CD86 costimulatory molecules on maturing APCs. LPS prevents deletion of allospecific CD8+ T cells that directly recognize DST even when the DST is deficient in these molecules. However, there are alternative costimulatory molecules expressed by mature APCs that could rescue CD8+ T cells from apoptosis and generate primed CTLs in the absence of CD40-CD154 interaction (47).

IFN-αβ can inhibit naive T cell activation (48) and induce Ag-independent attrition of naive and memory T cells (49), but under certain conditions can provide a costimulatory “signal 3” to naive CD8+ T cells and stimulate their expansion (50, 51). In animals not receiving our tolerance induction protocol, we observed only a small attrition of CD8+ T cells following LPS injection (13) but a more dramatic attrition after injection with poly (I:C) (49, 52), consistent with the different amounts of IFN-αβ induced.

We do document that a host population is responding to IFN-αβ. This is demonstrated by the fact that LPS and poly(I:C) fail to shorten allograft survival in IFN-RI–/– mice treated with costimulation blockade. It is possible that IFN-αβ is providing a signal directly to CD8+ T cells (50). However, it is also possible that IFN-αβ is acting on host dendritic cells as the initial player in a larger cascade of events, such as the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules or the production of additional cytokines (45). Experiments are currently underway to identify the key population(s) that is responding to IFN-αβ and is responsible for abrogating tolerance induction in our experiments.

The important role that the innate immune system, and TLRs in particular, play in solid organ rejection has only recently been appreciated (6, 7). Although many of the mechanistic studies have been performed in small rodent models, there is mounting evidence that TLRs play an equally important role in human allograft rejection. Specific TLR4 polymorphisms are now linked with an improved outcome in human recipients of lung (53, 54) and kidney (55, 56) allografts. Interestingly, one study found that certain TLR4 polymorphisms in the host but not the allograft donor confer a protective effect (53), in support of our current and previous (13) findings that TLR activation shortens allograft survival by acting at the level of the host. There is, however, clinical evidence that TLR4 polymorphisms in the donor allograft has an impact on kidney survival (56), suggesting that the impact of TLRs may differ among tissue types, similar to the differential results that we observe between skin and islet allografts.

Our observations illustrate the increasing complexity of transplantation biology, but also clearly reveal that one major element at the center of those complexities is IFN-αβ. We have shown that the strength of innate immune activation, the deletion of alloreactive CTLs, and the differential susceptibility of islet and skin grafts to tolerance induction can all be viewed as functions of the IFN-αβ response. Because signaling through type 1 IFN appears to be a central mechanism by which TLR agonists modulate adaptive immunity, strategies to target type 1 IFN signaling pathways may be important for successful translation of experimental transplantation tolerance protocols to clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Paquin, Linda Leehy, and Elaine Norowski for their technical assistance in islet isolation and transplantation. We also thank Cindy Bell, Jean Leif, and Amy Cuthbert for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI46629, DK53006, AI17672, and AI51405; institutional Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant DK32520; Juvenile Diabetes Foundation; and International Grants 1-2002-396 and 1-2004-548.

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used in this paper: DST, donor-specific transfusion; IFN-RI, type I IFN receptor; MST, median survival time; poly(I:C), polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid; KU, kilounit; DES, Desiré mAb.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Akira S. TLR signaling. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;311:1–16. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutler B, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Crozat K, Croker B, Rutschmann S, Du X, Hoebe K. Genetic analysis of host resistance: toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:353–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner H. Endogenous TLR ligands and autoimmunity. Adv. Immunol. 2006;91:159–173. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)91004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoebe K, Jiang Z, Tabeta K, Du X, Georgel P, Crozat K, Beutler B. Genetic analysis of innate immunity. Adv. Immunol. 2006;91:175–226. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)91005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:823–835. doi: 10.1038/nri1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obhrai J, Goldstein DR. The role of toll-like receptors in solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:497–502. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188124.42726.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein DR. Toll-like receptors and other links between innate and acquired alloimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2004;16:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossini AA, Greiner DL, Mordes JP. Induction of immunological tolerance for transplantation. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:99–141. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forman D, Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, Mordes JP, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Viral abrogation of stem cell transplantation tolerance causes graft rejection and host death by different mechanisms. J. Immunol. 2002;168:6047–6056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, Daniels KA, Brehm MA, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J. Virol. 2000;74:2210–2218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2210-2218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR, Shirasugi N, Durham MM, Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Onami T, Lanier JG, Kokko KE, et al. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1887–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Wang T, Zhou P, Ma L, Yin D, Shen J, Molinero L, Nozaki T, Phillips T, Uematsu S, et al. TLR engagement prevents transplantation tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:2282–2291. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornley TB, Brehm MA, Markees TG, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Welsh RM, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. TLR agonists abrogate costimulation blockade-induced prolongation of skin allografts. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1561–1570. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snanoudj R, de Preneuf H, Creput C, Arzouk N, Deroure B, Beaudreuil S, Durrbach A, Charpentier B. Costimulation blockade and its possible future use in clinical transplantation. Transplant. Int. 2006;19:693–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen CP, Knechtle SJ, Adams A, Pearson T, Kirk AD. A new look at blockade of T-cell costimulation: a therapeutic strategy for long-term maintenance immunosuppression. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:876–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker DC, Greiner DL, Phillips NE, Appel MC, Steele AW, Durie FH, Noelle RJ, Mordes JP, Rossini AA. Survival of mouse pancreatic islet allografts in recipients treated with allogeneic small lymphocytes and antibody to CD40 ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9560–9564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markees TG, Phillips NE, Gordon EJ, Noelle RJ, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Long-term survival of skin allografts induced by donor splenocytes and anti-CD154 antibody in thymectomized mice requires CD4+ T cells, interferon-γ, and CTLA4. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:2446–2455. doi: 10.1172/JCI2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenyon NS, Fernandez LA, Lehmann R, Masetti M, Ranuncoli A, Chatzipetrou M, Iaria G, Han DM, Wagner JL, Ruiz P, et al. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in baboons treated with humanized anti-CD154. Diabetes. 1999;48:1473–1481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.7.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenyon NS, Chatzipetrou M, Masetti M, Ranuncoli A, Oliveira M, Wagner JL, Kirk AD, Harlan DM, Burkly LC, Ricordi C. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in rhesus monkeys treated with humanized anti-CD154. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwakoshi NN, Mordes JP, Markees TG, Phillips NE, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Treatment of allograft recipients with donor specific trans-fusion and anti-CD154 antibody leads to deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells and prolonged graft survival in a CTLA4-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 2000;164:512–521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YS, Li XC, Zheng XX, Wells AD, Turka LA, Strom TB. Blocking both signal 1 and signal 2 of T-cell activation prevents apoptosis of alloreactive T cells and induction of peripheral allograft tolerance. Nat. Med. 1999;5:1298–1302. doi: 10.1038/15256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells AD, Li XC, Li YS, Walsh MC, Zheng XX, Wu ZH, Nuñez G, Tang AM, Sayegh M, Hancock WW, et al. Requirement for T-cell apoptosis in the induction of peripheral transplantation tolerance. Nat. Med. 1999;5:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwakoshi NN, Markees TG, Turgeon NA, Thornley T, Cuthbert A, Leif JH, Phillips NE, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Skin allograft maintenance in a new synchimeric model system of tolerance. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6623–6630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua C, Boyer C, Buferne M, Schmitt-Verhulst AM. Monoclonal antibodies against an H-2Kb-specific cytotoxic T cell clone detect several clone-specific molecules. J. Immunol. 1986;136:1937–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubinstein S, Familletti PC, Pestka S. Convenient assay for inter-ferons. J. Virol. 1981;37:755–758. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.2.755-758.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brehm MA, Daniels KA, Ortaldo JR, Welsh RM. Rapid conversion of effector mechanisms from NK to T cells during virus-induced lysis of allogeneic implants in vivo. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6663–6671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brehm MA, Mangada J, Markees TG, Pearson T, Daniels KA, Thornley TB, Welsh RM, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Rapid quantification of naive alloreactive T cells by TNF-α production and correlation with allograft rejection in mice. Blood. 2007;109:819–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-008219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tesar BM, Zhang J, Li Q, Goldstein DR. TH1 immune responses to fully MHC mismatched allografts are diminished in the absence of MyD88, a Toll-like receptor signal adaptor protein. Am. J. Transplant. 2004;4:1429–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang DC, Gopalkrishnan RV, Wu Q, Jankowsky E, Pyle AM, Fisher PB. mda-5: an interferon-inducible putative RNA helicase with double-stranded RNA-dependent ATPase activity and melanoma growth-suppressive properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:637–642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022637199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders LR, Barber GN. The dsRNA binding protein family: critical roles, diverse cellular functions. FASEB J. 2003;17:961–983. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0958rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Iwabe T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Differential involvement of IFN-β in Toll-like receptor-stimulated dendritic cell activation. Int. Immunol. 2002;14:1225–1231. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker WE, Nasr IW, Camirand G, Tesar BM, Booth CJ, Goldstein DR. Absence of innate MyD88 signaling promotes inducible allograft acceptance. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5307–5316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bettelli E, Carrier YJ, Gao WD, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graca L, Honey K, Adams E, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. Cutting edge: anti-CD154 therapeutic antibodies induce infectious transplantation tolerance. J. Immunol. 2000;165:4783–4786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banuelos SJ, Markees TG, Phillips NE, Appel MC, Cuthbert A, Leif J, Mordes JP, Shultz LD, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Regulation of skin and islet allograft survival in mice treated with costimulation blockade is mediated by different CD4+ cell subsets and different mechanisms. Transplantation. 2004;78:660–667. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000130449.05412.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitani Y, Takaoka A, Kim SH, Kato Y, Yokochi T, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. Cross talk of the interferon-α/β signalling complex with gp130 for effective interleukin-6 signalling. Genes Cells. 2001;6:631–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones ND, Turvey SE, Van Maurik A, Hara M, Kingsley CI, Smith CH, Mellor AL, Morris PJ, Wood KJ. Differential susceptibility of heart, skin, and islet allografts to T cell-mediated rejection. J. Immunol. 2001;166:2824–2830. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips NE, Markees TG, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Blockade of CD40-mediated signaling is sufficient for inducing islet but not skin transplantation tolerance. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3015–3023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tailor P, Tamura T, Ozato K. IRF family proteins and type I inter-feron induction in dendritic cells. Cell Res. 2006;16:134–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hahm B, Trifilo MJ, Zuniga EI, Oldstone MB. Viruses evade the immune system through type I interferon-mediated STAT2-dependent, but STAT1-independent, signaling. Immunity. 2005;22:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gil MP, Salomon R, Louten J, Biron CA. Modulation of STAT1 protein levels: a mechanism shaping CD8 T-cell responses in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:987–993. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNally JM, Zarozinski CC, Lin MY, Brehm MA, Chen HD, Welsh RM. Attrition of bystander CD8 T cells during virus-induced T-cell and interferon responses. J. Virol. 2001;75:5965–5976. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5965-5976.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bahl K, Kim SK, Calcagno C, Ghersi D, Puzone R, Celada F, Selin LK, Welsh RM. IFN-induced attrition of CD8 T cells in the presence or absence of cognate antigen during the early stages of viral infections. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4284–4295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmer SM, Burch LH, Davis RD, Herczyk WF, Howell DN, Reinsmoen NL, Schwartz DA. The role of innate immunity in acute allograft rejection after lung transplantation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:628–632. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-447OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer SM, Burch LH, Trindade AJ, Davis RD, Herczyk WF, Reinsmoen NL, Schwartz DA. Innate immunity influences long-term outcomes after human lung transplant. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005;171:780–785. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1129OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ducloux D, Deschamps M, Yannaraki M, Ferrand C, Bamoulid J, Saas P, Kazory A, Chalopin JM, Tiberghien P. Relevance of Toll-like receptor-4 polymorphisms in renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2454–2461. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palmer SM, Burch LH, Mir S, Smith SR, Kuo PC, Herczyk WF, Reinsmoen NL, Schwartz DA. Donor polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor-4 influence the development of rejection after renal transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2006;20:30–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]