Abstract

Background:

Many studies have suggested that major depressive disorder (MDD) is often associated with cognitive dysfunction. Despite this, guidance addressing assessment of cognitive dysfunction in MDD is lacking. The aim of this study was to examine psychiatrists’ perceptions and evaluation of cognitive dysfunction in routine practice in MDD patients across different countries.

Method:

A total of 61 psychiatrists in the US, Germany, France, Spain, Hong Kong, and Australia participated in an online survey about perceptions of cognitive dysfunction in MDD patients, evaluation of cognition and instruments used in cognitive evaluation.

Results:

Most psychiatrists reportedly relied on patient history interviews for cognitive evaluation (83% in France and approximately 60% in the USA, Germany, Australia and Hong Kong). The remainder used a cognitive instrument or a combination of cognitive instrument and patient history interview for assessment. Of those using instruments for cognitive assessment, only nine named instruments that were appropriate for cognitive evaluation. The remainder reported other clinical measures not intended for cognitive evaluation.

Conclusions:

Overall, psychiatrists in routine clinical practice value the assessment of cognitive in MDD. However, there is a lack of standardization in these assessments and misconceptions regarding proper assessment.

Keywords: cognitive dysfunction, cognitive instruments, major depressive disorder, neuropsychological tests

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mental disease characterized by reduced mood, low self-esteem and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. MDD is one of the most prevalent mood disorders; the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) reported a lifetime prevalence of 16.2% and a 12-month prevalence of 6.6% in the US population [Kessler et al. 2005]. In Europe, the 12-month prevalence was estimated at 6.9% [Wittchen et al. 2011]. The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks depression as the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide [Murray and Lopez, 1996] and projects that it will be the second leading cause of disability by 2020 [Lopez and Murray, 1998].

MDD does not only affect mood. It has also been widely associated with deficits in cognition [Baudic et al. 2004; Beats et al. 1996; Grant et al. 2001; Maalouf et al. 2011; Merriam et al. 1999; Nebes et al. 2003; Purcell et al. 1997; Reppermund et al. 2007]. Cognitive symptoms of diminished ability to concentrate and indecisiveness are part of the diagnostic classification of MDD according to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). MDD has been shown to affect cognitive domains of attention, concentration and memory. Other affected domains may include executive function, social cognitive performance, reasoning and problem solving. The extent to which these domains are affected in MDD is still a matter of discussion among researchers [Austin et al. 2001; Gualtieri et al. 2006].

Given the centrality of cognitive dysfunction in MDD, it would follow that assessment of cognition is an important part of MDD disease evaluation. In actuality, little is known about physician perceptions of cognitive dysfunction in MDD or the clinical assessment of cognitive deficits in MDD in routine practice. Currently, there is no guidance for assessing cognitive dysfunction in MDD. Additionally, little is known about the clinical use of cognitive assessment instruments. Given the lack of information on this issue, the purpose of the survey was to examine: (1) psychiatrists’ perceptions of cognitive dysfunction in MDD; (2) routine assessment of cognitive dysfunction in MDD patients in clinical practice; and (3) use of cognitive dysfunction instruments in clinical assessment.

Methodology

Study design

In March 2012, 786 psychiatrists from 6 countries were identified from a proprietary physicians list and were invited via email to participate in a cross-sectional, web-based survey. Psychiatrists from the US, France, Germany, Australia, Spain and Hong Kong were eligible to complete the survey provided they: (1) did not practice psychoanalysis; (2) prescribed drug therapies for their patients; (3) regularly assessed cognition in patients; (4) saw at least 50 patients per month with schizophrenia, MDD and bipolar disorder (BPD); and (5) obtained their medical degree between 1977 and 2009. All psychiatrists received the same set of questions. The survey link was disabled when the desired number of psychiatrists in each country completed the survey and psychiatrists were compensated by between €70 and €177 for their time depending on country.

Survey components

The survey was developed by Creativ-Ceutical and divided into three sections, each with multiple subparts. The first section of the questionnaire comprised questions for eligibility screening. The survey was terminated if any exclusion criteria were met. The second section consisted of sociodemographic questions regarding gender, country of residence, practice setting (rural or urban) and work environment (public, private or both). The last section contained questions on psychiatrists’ knowledge, attitude and insight on: (1) the cognition status of their MDD patients; (2) standard guidelines for cognition assessment; (3) the methods of routine cognitive assessment; and (4) use of cognitive assessment instruments and perception of robustness and sensitivity of such instruments. Answers included yes/no responses, rankings, multiple choice and open-ended responses.

Survey responses on the method of cognitive assessment were captured by three options: (1) use of patient history interview; (2) use of cognitive function instruments; and (3) use of both methods. The patient history interview method included gathering qualitative information about the patient’s ability to act in a socially apt manner and to organize and communicate information effectively. Cognitive assessment instruments were defined as the use of standardized tools to obtain a score relative to the norm for cognitive domains.

The cognitive instruments reportedly used by psychiatrists were assessed for appropriateness for use in MDD against the five criteria for cognitive assessment instruments proposed by the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) initiative. The MATRICS program was initially designed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to support the development of pharmacological agents for improving neurocognitive impairments in schizophrenia [Kern et al. 2004]. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) for clinical trial [Nuechterlein and Green, 2006] is a battery of tests approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [Buchanan et al. 2005] based on five preset criteria: (1) test–retest reliability; (2) utility as a repeated measure; (3) relationship to functional outcome; (4) potential changeability in response to pharmacological agents; and (5) tolerability and practicality for clinical setting. Instruments were assessed for these criteria by an expert group and Creativ-Ceutical in-house statisticians. Though the MATRICS criteria are intended for use in schizophrenia, the criteria are being tested for selection of instruments for MDD [Green et al. 2004; Nuechterlein et al. 2008]. Therefore, this study used these criteria for evaluation of reported cognitive instruments for use in MDD.

Psychiatrists answered questions separately for schizophrenia, MDD and BPD patients. For the purpose of this study, only MDD-related questions were analyzed. The combined responses to questions on all three diseases are reported in a separate analysis.

The entire survey took approximately 45 minutes to complete and participating psychiatrists were compensated for their time. The survey was designed by Creativ-Ceutical and was approved and sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals International.

Data collection and analysis

The survey was translated into French, German and Spanish, and respondents answered questions in their native language; psychiatrists in Hong Kong completed the survey in English. All responses were translated back into English and stored in a comprehensive database for analysis. Psychiatrists’ understanding of the questionnaire was evaluated to identify any inconsistency in answers. Means were calculated for continuous variables and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables overall and by country. All personal data collected during the study were treated confidentially. The study sponsor had no role in the data collection or analysis. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not sought in this study as this constituted market research.

Results

Sociodemographic profile

A total of 61 psychiatrists from six countries completed the survey [USA (n = 15), Germany (n = 10), France (n = 12), Spain (n = 10), Hong Kong (n = 6) and Australia (n = 8)]. Gender and working environment distributions were similar between countries. Overall, the sample was 64% male and 36% female. More than 80% of the participants reported working in an urban environment. Hong Kong was an exception, with all male participants working in an urban environment. The average psychiatrist in the sample had 18 years of clinical practice experience. This number was slightly lower in Hong Kong, with an average of 12.5 years of clinical experience. The distribution of public and private workers differed among countries. In the USA, most participants worked in private organizations, while in Hong Kong all participants worked privately. In France, Germany and Australia, the majority of participants worked in the public sector. In Spain, all participants worked in the public sector (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the demographic and professional background of the selected psychiatrists.

| Overall | USA | France | Germany | Spain | Australia | Hong Kong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of psychiatrists | 61 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 64% | 73% | 58% | 70% | 40% | 50% | 100% |

| Female | 36% | 27% | 42% | 30% | 60% | 50% | 0% |

| Work environment | |||||||

| Urban | 87% | 80% | 83% | 80% | 90% | 100% | 100% |

| Rural | 13% | 20% | 17% | 20% | 10% | 0% | 0% |

| Practice setting | |||||||

| Private | 35% | 73% | 17% | 20% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Public | 58% | 20% | 83% | 80% | 100% | 63% | 0% |

| Both | 7% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 37% | 0% |

| Average years of practice (SD) | 18 (3.5) | 22 (7.3) | 20 (6.4) | 20 (6.6) | 18 (7.4) | 16 (5.0) | 12.5 (6.0) |

Percentages for repartition of gender, work environment and practice setting are calculated from total number of respondents in each country. Years of practice were evaluated indirectly by asking the psychiatrists the year of completion of their MD degree; they are given as the average number for each country.

SD, standard deviation.

Patients’ profile

On average, participants saw approximately 67 MDD patients per month. The highest mean number of MDD patients seen was in the USA (n = 102) and Germany (n = 96). Australia saw the lowest mean number of MDD patients (n = 34) (Table 2). The majority of participants reported regularly assessing cognitive dysfunction in their MDD patients. Those who reported not assessing cognition in MDD (7%) reported that this was not a relevant aspect of the disease.

Table 2.

Patients’ profile covered by the survey.

| Average percentage (%) of MDD patients per month per country |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | France | Germany | Spain | Australia | Hong Kong | |

| Average number of patients (SD) | 102 (57.3) | 50 (38.2) | 96 (111.0) | 47 (37.5) | 34 (20.4) | 76 (57.2) |

| Level of cognitive impairment severity | ||||||

| No cognitive impairment | 55% | 19% | 24% | 30% | 51% | 0% |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 22% | 30% | 20% | 35% | 36% | 38% |

| Moderate cognitive impairment | 17% | 33% | 24% | 23% | 10% | 33% |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 6% | 18% | 32% | 12% | 3% | 29% |

Level of the cognitive impairment severity of MDD patients according to psychiatrists’ judgment regardless of the method of assessment used. Levels of cognitive impairment were predetermined by the survey as no cognitive impairment, mild cognitive impairment, moderate cognitive impairment and severe cognitive impairment. Results are shown as the average percentage of MDD patients per country for each level of cognitive impairment.

MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation.

When participants estimated the level of cognitive dysfunction in their MDD patients, US psychiatrists reported that roughly 45% of their MDD patients were cognitively impaired; among these, 6% were reported to be severely cognitively impaired. In Australia, 51% of patients were judged to have no cognitive impairment. Psychiatrists in all other countries estimated ≥50% of their MDD patients had cognitive dysfunction. In Hong Kong, psychiatrists estimated 100% of MDD patients were cognitively impaired and 29% of these were severely impaired (Table 2).

Assessment of cognitive dysfunction for patients with MDD

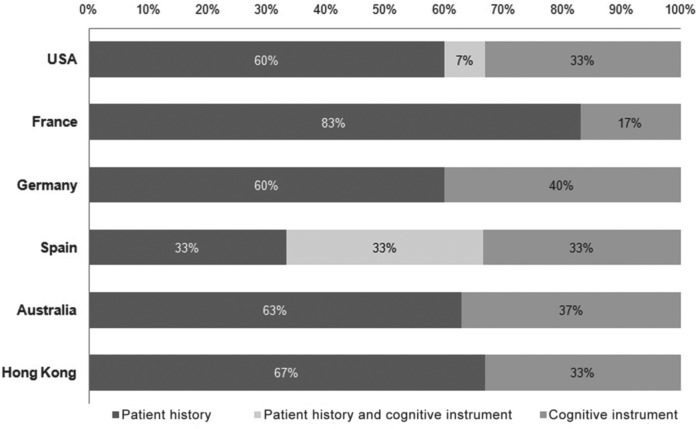

In assessing cognitive dysfunction, most psychiatrists (61%) relied solely on the patient history interview. The remainder reported using cognitive instruments or a combination of cognitive instruments and patient history interview for cognitive evaluation. The USA and Spain were the only countries in which some psychiatrists used both the patient history interview and a cognitive instrument. Spanish psychiatrists reported equal use of patient history interview and cognitive instruments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of methods used for evaluation of cognitive dysfunction in routine clinical practice.

Survey responses were categorized into three options: (1) use of patient history interview; (2) use of cognition instruments; and (3) use of both these methods. Results are shown as a percentage.

Cognitive dysfunction assessment using instruments

Psychiatrists who reported using instruments for cognitive assessment were asked to specify the names of the instruments used (up to 10). The Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) was the most commonly cited instrument by psychiatrists across all countries (n = 19). While it is used for the assessment of cognition in some disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease, MMSE has not been tested in MDD patients. Other cognitive function instruments listed by psychiatrists were designed to diagnose mental diseases or to evaluate illness severity rather than cognition status. Eight psychiatrists cited instruments for assessing depression severity rather than cognitive assessment tools, including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and Personal Health Questionnaire Depression scale (PHQ-9). One psychiatrist reported the use of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), a tool to assess symptoms in schizophrenia, and one reported the neuropsychological battery of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Many psychiatrists reported other clinical measures or irrelevant answers (e.g. ‘clinical interview’, ‘neuropsychological test’, ‘lobe clinical assessment’, etc.). These answers were aggregated as ‘other’ for the analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of use of instruments by psychiatrists (up to 10) for assessment of cognition in MDD patients.

All instruments cited are reported in terms of frequency. The section labeled ‘other’ includes other clinical measures or irrelevant answers. Instruments suitable for assessment of cognitive dysfunction according to MATRICS criteria are highlighted in black. Instruments suitable for assessment of cognitive dysfunction in MDD according to MATRICS criteria are highlighted in dark grey.

AMT, Autobiographical Memory Test; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CAS, Coping Attitudes Scale; CAMCOG, Cambridge Cognitive Examination; CAMDEX, Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly; CERAD, The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; FUCAS, Functional Cognitive Assessment Scale; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAWIE-R, German version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS); IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MMSE, Folstein Mini Mental Status; Nucog, Neuropsychiatry Unit Cognitive Assessment Tool; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PEPP, Prevention and Early intervention Program for Psychoses; PHQ-9, Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale.

Of the 29 instruments named by psychiatrists, only 6 could be considered appropriate cognitive assessment tools based on the MATRICS criteria: Trail Making Test and Wechsler Memory Scale (MCCB subtests), the Stroop test (CogState subtest), Digit span (WAIS battery subtest), Hawie-R (German version of the WAIS battery tests) and Coping Attitudes Scale (CAS) (Figure 2). Among these tests, CAS, reported by one US psychiatrist, is the only instrument that has been evaluated in an MDD population [DeJong and Verholser, 2007].

Discussion

This survey was intended to gain an understanding of practicing physicians’ perceptions of cognitive dysfunction in MDD and real-world use of cognitive assessment instruments. Despite a small sample, the participants were diverse in terms of work environments, practice settings, clinical experience and countries (Table 1).

The findings of this study show that psychiatrists are aware of cognitive dysfunction in MDD patients; psychiatrists classified 66% of MDD patients as mildly to severely cognitively impaired. This result must be interpreted with the understanding that eligibility criteria excluded psychiatrists who did not routinely assess cognitive dysfunction in MDD, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Additionally, results of cognitive classification must be interpreted with caution as these were based on psychiatrists’ self-report. Psychiatrists reported a variety of different methods for cognitive evaluation and different methods may lead to different cognitive classification.

Despite the heightened awareness and substantial evidence that depression negatively affects cognition, formal cognitive evaluation plays a small part in the clinical management of MDD patients [Gualtieri and Morgan, 2008]. The majority of psychiatrists reported evaluation of cognition through the patient history interview. While the patient history interview is commonly used in clinical practice, it may not allow an exhaustive and accurate cognitive diagnosis. Cognitive domains of psychomotor slowing, memory or language functions [Gualtieri et al. 2006], visual learning, verbal learning and social performance [Chamberlain and Sahakian, 2004; Cusi et al. 2011] are seldom or ever evaluated in the patient history interview. This information is important for practitioners to remember if relying solely on the patient history interview as their method of cognitive assessment.

Cognitive instruments provide an objective assessment of cognitive dysfunction. Ideally, these should have a complementary role to the patient history interview. The present study revealed that, of those psychiatrics using cognitive instruments in MDD, few were actually using appropriate instruments (Figure 2). Many of these instruments were inappropriate for the intended population and disease state. Further, many of the cited instruments were not even tests of cognition but rather of disease severity. Taken together, these results show there may be misuse and confusion regarding instruments for assessing cognitive dysfunction in MDD patients.

It is important to keep in mind that the results of this study are based on a small sample of psychiatrists from each country. Additionally, these psychiatrists volunteered to participate from a proprietary list of psychiatrists. Therefore, these samples may not be representative of general population of psychiatrists. Future studies may further test these results with a larger sample of psychiatrists.

Standardized guidance on cognitive assessment in routine clinical practice may address many of the deficits seen in this study, such as the high number of psychiatrists relying only on the patient history interview for cognitive evaluation (Figure 1) and the high rate of misuse of cognitive assessment instruments (Figure 2).

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the importance of increasing awareness among psychiatrists of appropriate cognitive assessments and use of these instruments.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S.

Conflict of interest statement: The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S. The sponsor had no role in the study design or in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. J.S. and K.A. were employed by Takeda Pharmaceuticals at the time of the study.

Contributor Information

Emna El Hammi, Creativ-Ceutical, Deerfield, IL, USA.

Jennifer Samp, Takeda Global Research and Development Center, Deerfield, IL, USA.

Cécile Rémuzat, Creativ-Ceutical, Deerfield, IL, USA.

Jean-Paul Auray, University of Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, Cedex, France.

Michel Lamure, University of Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, Cedex, France.

Samuel Aballéa, Creativ-Ceutical, Deerfield, IL, USA.

Amna Kooli, Creativ-Ceutical, Deerfield, IL, USA.

Kasem Akhras, Takeda Global Research and Development Center, Deerfield, IL, USA.

Mondher Toumi, University of Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon I, UFR d’Odontologie, 11 rue Guillaume Paradin, 69372 Lyon, Cedex 08, France.

References

- Austin M., Mitchell P., Goodwin G. (2001) Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry 178: 200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudic S., Tzortzis C., Barba G., Traykov L. (2004) Executive deficits in elderly patients with major unipolar depression. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 17: 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beats B., Sahakian B., Levy R. (1996) Cognitive performance in tests sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in the elderly depressed. Psychol Med 26: 591–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan R., Davis M., Goff D., Green M., Keefe R., Leon A., et al. et al (2005) A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 31: 5–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain S., Sahakian B. (2004) Cognition in mania and depression: psychological models and clinical implications. Curr Psychiatry Rep 6: 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusi A., Macqueen G., Spreng R., McKinnon M. (2011) Altered empathic responding in major depressive disorder: relation to symptom severity, illness burden and psychosocial outcome. Psychiatry Res 188: 231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong T., Overholser J. (2007) Coping attitudes scale: psychometric properties of a measure of positive attitudes in depression. Cogn Ther Res 31: 39–50 [Google Scholar]

- Grant M., Thase M., Sweeney J. (2001) Cognitive disturbance in outpatient depressed younger adults: evidence of modest impairment. Biol Psychiatry 50: 35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M., Nuechterlein K., Gold J., Barch D., Cohen J., Essock S., et al. et al (2004) Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biol Psychiatry 56: 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri C., Johnson L., Benedict K. (2006) Neurocognition in depression: patients on and off medication versus healthy comparison subjects. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 18: 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri C., Morgan D. (2008) The frequency of cognitive impairment in patients with anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder: an unaccounted source of variance in clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 69: 1122–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern R., Green M., Nuechterlein K., Deng B. (2004) NIMH-MATRICS survey on assessment of neurocognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 72: 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R., Chiu W., Demler O., Merikangas K., Walters E. (2005) Prevalence, severity and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A., Murray C. (1998) The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med 4: 1241–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf F., Brent D., Clark L., Tavitian L., McHugh R., Sahakian B., et al. (2011) Neurocognitive impairment in adolescent major depressive disorder: state versus trait illness markers. J Affect Disord 133: 625–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam E., Thase M., Haas G., Keshavan M., Sweeney J. (1999) Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in depression determined by Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance. Am J Psychiatry 156: 780–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C., Lopez A. (1996) Evidence-based health policy – lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science 274: 740–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebes R., Pollock B., Houck P., Butters M., Mulsant B., Zmuda M., et al. (2003) Persistence of cognitive impairment in geriatric patients following antidepressant treatment: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial with nortriptyline and paroxetine. J Psychiatr Res 37: 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein K., Green M. (2006) MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery Manual. Los Angeles, USA: MATRICS Assessment Inc [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein K., Green M., Kern R., Baade L., Barch D., Cohen J., et al. (2008) The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry 165: 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell R., Maruff P., Kyrios M., Pantelis C. (1997) Neuropsychological function in young patients with unipolar major depression. Psychol Med 27: 1277–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppermund S., Zihl J., Lucae S., Horstmann S., Kloiber S., Holsboer F., et al. (2007) Persistent cognitive impairment in depression: the role of psychopathology and altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) system regulation. Biol.Psychiatry 62: 400–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H., Jacobi F., Rehm J., Gustavsson A., Svensson M., Jönsson B., et al. (2011) The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21: 655–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]