Significance

Humans usually punish free riders but refuse to sanction those who cooperate but do not punish. However, such second-order punishment is essential to maintain cooperation. The central authorities established in modern societies punish both free riders and tax evaders. This is a paradox: would individuals who do not engage in second-order punishment strive for an authority that does? We address this puzzle with a mathematical model and an economic experiment. When individuals can choose between authorities by migrating between different communities, we find a costly bias against second-order punishment. When subjects use a majority vote instead, they vote for an authority with second-order punishment. These findings also suggest that other pressing social dilemmas could be solved by democratic voting.

Keywords: evolution of cooperation, pool punishment, institution formation

Abstract

Individuals usually punish free riders but refuse to sanction those who cooperate but do not punish. This missing second-order peer punishment is a fundamental problem for the stabilization of cooperation. To solve this problem, most societies today have implemented central authorities that punish free riders and tax evaders alike, such that second-order punishment is fully established. The emergence of such stable authorities from individual decisions, however, creates a new paradox: it seems absurd to expect individuals who do not engage in second-order punishment to strive for an authority that does. Herein, we provide a mathematical model and experimental results from a public goods game where subjects can choose between a community with and without second-order punishment in two different ways. When subjects can migrate continuously to either community, we identify a bias toward institutions that do not punish tax evaders. When subjects have to vote once for all rounds of the game and have to accept the decision of the majority, they prefer a society with second-order punishment. These findings uncover the existence of a democracy premium. The majority-voting rule allows subjects to commit themselves and to implement institutions that eventually lead to a higher welfare for all.

The success of collective action and the maintenance of commonly shared infrastructure is often endangered by free riders, subjects who reap the benefits of public goods without contributing to them (1, 2). To mitigate the free riders’ destructive potential, many communities install specialized authorities that monitor the subjects’ behavior and sanction wrong-doers (3–7). Examples, such as modern courts and the police system, indicate that the maintenance of such institutions is costly. They also constitute a commonly shared infrastructure, which can be exploited just as the original public good that the institution was designed for to protect. Thus, a second-order dilemma arises.

Second-order dilemmas appear in various forms and are considered as a serious obstacle to the evolution of cooperation (8–10). For example, in the absence of a policing authority, group members may take the job onto themselves, punishing others directly. There is overwhelming evidence that subjects are willing to sanction free riders at a cost to themselves (11–14), although individuals typically refuse to exert second-order punishment (15). However, peer punishment can have detrimental consequences on welfare, as the punishment costs may override the benefits of increased cooperation (16) and due to the problems of antisocial punishment (17) and retaliation (18, 19). Peer punishment may pay in the long run, but only when interactions take place in small and stable groups (20). These restrictions may be the reason why modern states have abolished decentralized sanctioning (21).

To explain the transition from decentralized peer punishment to institutional pool punishment (22), recent theoretical and experimental evidence highlights the critical role of second-order punishment (23–26). These studies indicate that such institutions can only persist when they additionally punish individuals who do not support the central authority. The presence of a powerful authority restricts the subjects’ strategic options and effectively forces them to cooperate. As this implies a considerable loss of individual freedom, it is unclear under which conditions subjects would voluntarily submit to such a Leviathan (27). There are different views on this problem: Hardin argued that “we accept compulsory taxes because we recognize that voluntary taxes would favor the conscienceless” (2). However, previous studies have also shown that maintaining costly institutions may result in lower average payoffs (23, 25). Under which conditions would subjects agree to implement a central authority that enforces its continued existence with second-order punishment?

To investigate this question, we conducted an experimental public goods game. The experiment consisted of three independent blocks, each block having several rounds (Table 1 and Materials and Methods). During the first two blocks of the experiment, consisting of 10 rounds each, subjects first had to decide whether they want to participate in the game or abstain to secure a small payoff. Participants were then asked whether they want to pay taxes to a central authority and whether they want to cooperate by contributing money to a common pool. If at least one subject paid taxes, the central authority was established and either punished both noncontributors and tax evaders (institution with second-order punishment) or just noncontributors (institution without second-order punishment). If subjects failed to establish such an authority, the public goods game took the form of a conventional social dilemma (mutual cooperation was the optimal outcome for the group, in which case each individual’s best choice was to free ride).

Table 1.

Overview of the experimental design

|

In the first two blocks of the experiment, subjects gained experience with punishment institutions with and without second-order punishment (2OP). In the third block, subjects could choose between these two institutional rules. To avoid sequence effects, there are two versions of each treatment. Only the results of blocks II and III are analyzed further. In the subsequent figures, green colors refer to results of block II. Red and blue colors refer to results of block III, for the foot voting treatment and the majority voting treatment, respectively.

In the last block of the experiment, consisting of 15 rounds, subjects had to choose between an authority with or without second-order punishment. As the subjects’ choice may depend on the voting mechanism that allows individuals to choose between different alternatives (28), we distinguished two different treatments. (A) Subjects can migrate to either community (foot-voting treatment): here, subjects could choose in each round of the last block between an authority with or without second-order punishment. They only interacted with individuals who chose the same institutional rule. Previous experiments used such a voting scheme to show that humans prefer peer punishment institutions to punishment-free institutions (13), even if reputation allows for an alternative mechanism to govern the commons (14). (B) Subjects participate in a democratic vote (majority-voting treatment): subjects had to vote for their preferred institution in the beginning of the last block. The institutional rule that obtained a majority of votes was then implemented for all remaining 15 rounds and was imposed on all group members. Such a scheme of elected authorities can elicit higher contributions to public goods than randomly chosen authorities (29) and help subjects to coordinate on pool punishment systems with optimal parameters (30).

Results

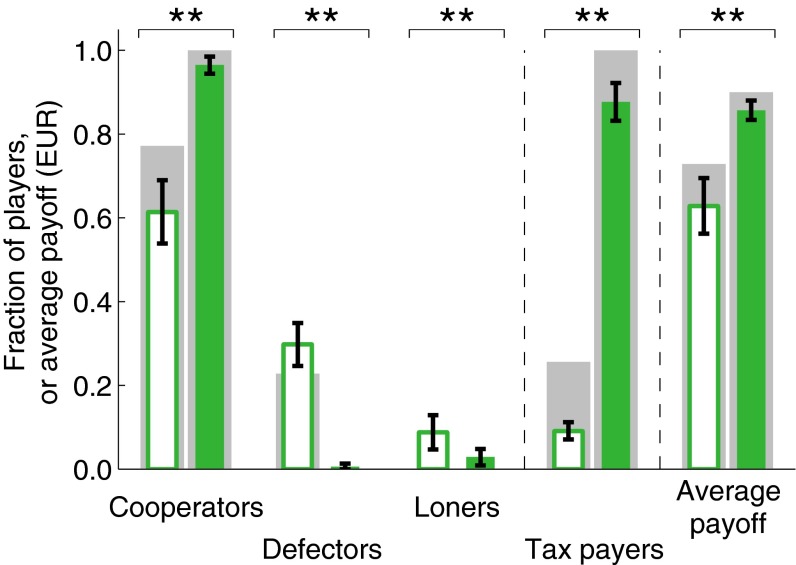

Based on a theoretical model (described in detail in the SI Text), we expected that only a minority of subjects would pay taxes if there is no punishment for tax evasion. As a consequence, we also predicted that authorities without second-order punishment would result in less cooperation and lower average payoffs. An analysis of block II of our experiments (in which subjects could not choose between different institutions) confirms these predictions (Fig. 1). Second-order punishment institutions facilitated higher average payoffs (payoffs increased from 0.63 to 0.86 Euro per round when tax evaders were punished, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,  ,

,  ,

,  ; we used two-tailed statistics throughout), and led to more cooperation (the fraction of cooperators increased from 61.4% to 96.5%, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,

; we used two-tailed statistics throughout), and led to more cooperation (the fraction of cooperators increased from 61.4% to 96.5%, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,  ,

,  ). This efficiency advantage of second-order punishment institutions suggests that subjects should prefer this institutional rule when given a choice in the last block, independent of the implemented voting rule.

). This efficiency advantage of second-order punishment institutions suggests that subjects should prefer this institutional rule when given a choice in the last block, independent of the implemented voting rule.

Fig. 1.

Second-order punishment promotes cooperation. The graph shows the fraction of cooperators (individuals who contribute to the common pool), defectors (individuals who do not contribute), loners (individuals who decide not to participate in the game), and the fraction of subjects paying taxes, as well as the resulting average payoff. Colored bars depict the experimental results of block II, with empty bars corresponding to rounds without second-order punishment, and filled bars showing rounds with second-order punishment. Two stars indicate significance at the  level (using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests). Gray bars depict the theoretical predictions based on a social learning model for the one-shot game (see SI Text for details). As predicted, second-order punishment resulted in more cooperation in the public goods game, as more subjects were willing to support the punishment institution by paying taxes. Overall, this led to a significant increase of average payoffs.

level (using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests). Gray bars depict the theoretical predictions based on a social learning model for the one-shot game (see SI Text for details). As predicted, second-order punishment resulted in more cooperation in the public goods game, as more subjects were willing to support the punishment institution by paying taxes. Overall, this led to a significant increase of average payoffs.

However, for the votes before the first round of the last block, we observed a significant treatment effect (Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

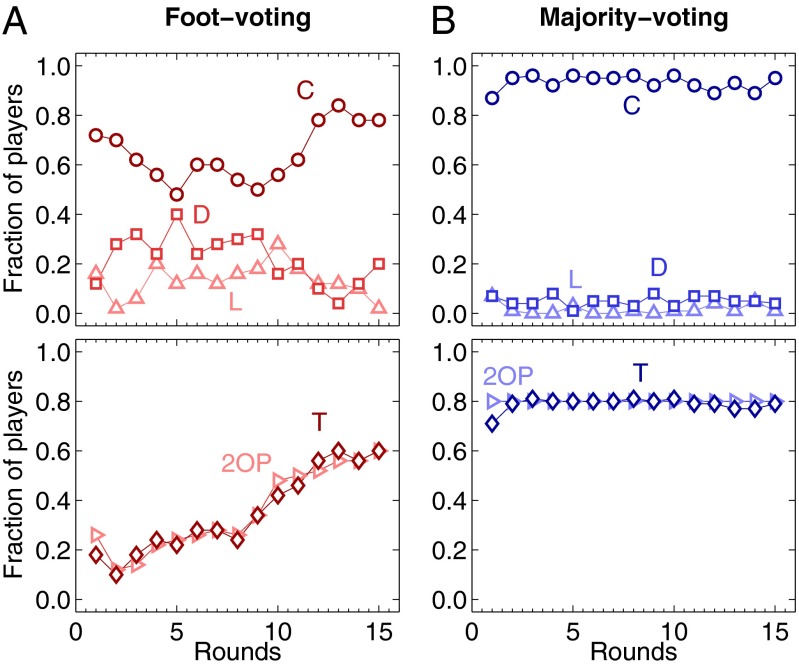

,  ). In foot-voting groups, subjects initially preferred institutions without second-order punishment (with 8 of 10 groups having a majority against second-order punishment in the first round of block III; Fig. 2A). Only the groups in the majority-voting treatment showed a clear preference for second-order punishment, with 12 of 15 groups voting for the respective institution (binomial test,

). In foot-voting groups, subjects initially preferred institutions without second-order punishment (with 8 of 10 groups having a majority against second-order punishment in the first round of block III; Fig. 2A). Only the groups in the majority-voting treatment showed a clear preference for second-order punishment, with 12 of 15 groups voting for the respective institution (binomial test,  ,

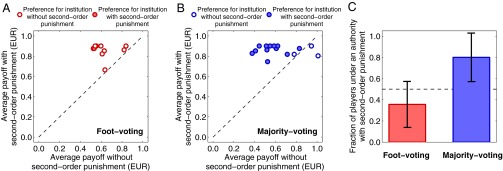

,  ; Fig. 2B). Over the course of the experiment, this treatment effect waned; by the end of the last block, in four more groups in the foot-voting treatment, the majority of players switched to second-order punishment. In total, 35.6% of the subjects in the foot-voting treatment played under an authority with second-order punishment compared with the 80.0% in the majority-voting treatment (Fig. 2C).

; Fig. 2B). Over the course of the experiment, this treatment effect waned; by the end of the last block, in four more groups in the foot-voting treatment, the majority of players switched to second-order punishment. In total, 35.6% of the subjects in the foot-voting treatment played under an authority with second-order punishment compared with the 80.0% in the majority-voting treatment (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Democratic decisions establish institutions with second-order punishment. (A and B) Horizontal axis shows the average payoff that each group obtained during block II when acting under an institution without second-order punishment, whereas the vertical axis shows the average payoff obtained during rounds with second-order punishment. Thus, for all groups above the diagonal, second-order punishment resulted in higher payoffs during block II. The filling of the symbol indicates the group’s vote in the first round of block III: the group symbol is filled if at least half of the group members voted for second-order punishment. Basing decisions on efficiency would imply that symbols above the dashed line are filled. (A) In the foot-voting treatment, only 2 of 10 groups had at least half of the players voting for an institution with second-order punishment (although all 10 groups earned, on average, more under such an institution). (B) Under the majority-voting rule, 12 of 15 groups voted for second-order punishment. (C) Over all 15 rounds of block III, subjects in the foot-voting treatment chose second-order punishment in 35.6% of all cases. In contrast, 80% of the subjects in the majority-voting treatment were governed by an institution with second-order punishment (see SI Text for further details on the subject’s voting behavior).

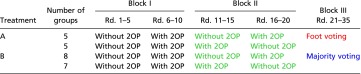

To study the dynamics during the third block, we compared the players’ strategies in the beginning (rounds 1–5) with the strategies in the end (rounds 11–15) (Fig. 3). Although behaviors in the majority-voting treatment were stable as predicted (none of the considered variables changed significantly over time), we found significant learning effects in the foot-voting treatment. Driven by a stronger preference for second-order punishment (rounds 1–5, 19.6%; rounds 11–15, 54.8%; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,  ,

,  ), we found a significant increase in the number of tax payers (rounds 1–5, 18.4%; rounds 11–15, 55.6%; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,

), we found a significant increase in the number of tax payers (rounds 1–5, 18.4%; rounds 11–15, 55.6%; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,  ,

,  ). The higher willingness to pay taxes resulted in a reduction of the number of defectors (rounds 1–5, 27.2%; rounds 11–15, 13.2%; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,

). The higher willingness to pay taxes resulted in a reduction of the number of defectors (rounds 1–5, 27.2%; rounds 11–15, 13.2%; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test,  ,

,  ), whereas it had no significant impact on the number of cooperators or on the resulting average payoff.

), whereas it had no significant impact on the number of cooperators or on the resulting average payoff.

Fig. 3.

Social learning leads to a trend toward second-order punishment in block III. (Upper) Fraction of cooperators C, defectors D, and loners L in each round. (Lower) Fraction of players preferring an institution with second-order punishment (2OP), as well as the fraction of players who paid taxes (T). (A) Foot-voting groups learned to adopt institutions with second-order punishment, which led to an increase in the number of taxpayers, and to a reduction of the number of defectors. (B) In the majority-voting treatment, on the other hand, behaviors were stable.

Overall, payoffs in the foot-voting treatment were clearly below the payoffs under majority voting ( compared with € 0.86; Mann-Whitney U test,

compared with € 0.86; Mann-Whitney U test,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ). These findings indicate that foot voting has led to a costly bias in favor of unstable institutions without second-order punishment. This bias decreased over time, but it did not disappear completely. The lower payoffs in the foot-voting treatment are unexpected, as this treatment can give rise to smaller group sizes (subjects only interacted with those who voted for the same institution), which in turn facilitates cooperation (31). Postexperiment questionnaires suggest that subjects in the foot-voting treatment hoped that eventually everyone would play fair, such that there would be no need for a punishment institution. Typically, this hope did not come true; none of the groups in the foot-voting treatment and only one group in the majority-voting treatment managed to choose an institution without second-order punishment and to cooperate in all 15 rounds without paying taxes. The majority-voting rule, on the other hand, seemed to trigger subjects to make group-beneficial decisions. Indeed, for 14 of the 15 groups, the majority vote resulted in the institutional rule that proved to be more efficient in the preceding blocks (Fig. 2B; binomial test,

). These findings indicate that foot voting has led to a costly bias in favor of unstable institutions without second-order punishment. This bias decreased over time, but it did not disappear completely. The lower payoffs in the foot-voting treatment are unexpected, as this treatment can give rise to smaller group sizes (subjects only interacted with those who voted for the same institution), which in turn facilitates cooperation (31). Postexperiment questionnaires suggest that subjects in the foot-voting treatment hoped that eventually everyone would play fair, such that there would be no need for a punishment institution. Typically, this hope did not come true; none of the groups in the foot-voting treatment and only one group in the majority-voting treatment managed to choose an institution without second-order punishment and to cooperate in all 15 rounds without paying taxes. The majority-voting rule, on the other hand, seemed to trigger subjects to make group-beneficial decisions. Indeed, for 14 of the 15 groups, the majority vote resulted in the institutional rule that proved to be more efficient in the preceding blocks (Fig. 2B; binomial test,  ).

).

Discussion

Economic experiments have repeatedly shown that individuals are willing to punish free riders (11–14). At the same time subjects either abstain from second-order punishment opportunities (15), or they may even abuse them for perverse punishment (i.e., forms of punishment that have the effect of reducing future cooperation) (32). The subjects' reluctance to sanction nonpunishers is surprising because second-order punishment is of fundamental importance for the stability of decentralized peer punishment (33, 34), and it also plays a crucial role for the evolution of central pool punishment institutions (23–26). Indeed, in most societies today, central punishment institutions are funded by compulsory taxes rather than by voluntary contributions. The emergence of such authorities poses a puzzle: does this mean that individuals are able to implement institutions with second-order punishment, although the individuals themselves are not willing to engage in second-order punishment?

With an economic experiment, we investigated two possible routes for the emergence of central institutions with second-order punishment. In one treatment, subjects could choose between different institutions by migrating to the respective community, whereas in the other treatment, subjects could vote for their preferred institution in a democratic election. Our mathematical model of social learning (see SI Text for details) suggests in both cases that institutions with second-order punishment are more stable and result in higher payoffs. However, in our experiment only the subjects in the majority-voting treatment succeeded in implementing the corresponding authority. Subjects in the foot-voting treatment showed a costly bias in favor of institutions without second-order punishment. Various causes may be responsible for this positive effect of the majority-voting rule. First, the outcome of the democratic decision was binding for all 15 rounds of the last block; this may have triggered subjects to take a long-run perspective and to anticipate the risks and benefits of each punishment institution. Second, the decision to migrate to either community in the foot-voting treatment only affects each subject individually. When using a majority vote instead, individuals can bind each other. This option to bind each other may have triggered subjects to take a group perspective and to opt for the institution that leads to a beneficial group dynamics, rather than choosing an institution that promises individual advantages. Buchanan and Congleton argued that “persons agree to constraints on their own liberties in exchange for comparable constraints being imposed on the liberties of others.” (35) The majority-voting rule can be seen as a mechanism that helps individuals to implement such beneficial constraints.

Institutions are inherently unstable when they only apply to a subset of community members (36). A similar problem arises if institutions are only funded by such a subset (23–26, 37): when paying taxes occurs on a voluntary basis, tax evasion can lead to the breakdown of cooperation (as also shown in Fig. 1). Thus, the stability of many modern institutions requires second-order punishment, where subjects that do not support the central institution are punished just as ordinary free riders. Interestingly, the delegation of punishment to central institutions may in turn facilitate the emergence of second-order punishment: First, since institutions need to be funded in advance, second-order free riders (i.e., tax evaders) are easy to detect (23). Second, setting up a punishment institution to protect a community from wrong-doers may be expensive, but once the institution is established, extending its scope to prosecute also tax evaders seems to be relatively cheap. In this way, first-order and second-order punishment become linked: the same institution automatically engages in both forms of punishment. This linkage is critical for the maintenance of second-order punishment, as it removes the need for further levels of punishment (such as third-order punishment) to stabilize the lower levels (38). In peer punishment, it is not immediately clear how such a linkage between first-order and second-order punishment could evolve (33, 34). When punishment is delegated to a central authority instead, this linkage can be implemented easily.

We showed here that a pool punishment regime with second-order punishment can emerge if individuals have the freedom to bind each other with a majority vote, but not if they can individually reconsider their decision after each round. In our experiments, democracy prompts individuals to commit themselves and to make institutional choices that enhance the welfare of all.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design.

Experiments were conducted in November 2012 at the University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany, with 125 subjects recruited from a first-year course in biology. Twenty-five groups of five subjects played 35 rounds of a public goods game. In each round, players first had to choose between being a loner (fixed payoff of € 0.40) and taking part in the public goods game. Those subjects who decided to participate were then asked whether they want to pay taxes for a punishment institution. Individual taxes depended on the number of tax payers (which is a typical feature of models of coordinated punishment) (39, 40): if i is the number of tax payers, then the tax was set to  (institution without second-order punishment) and to

(institution without second-order punishment) and to  (institution with second-order punishment), respectively. These parameters reflect our assumption that a punishment institution comes with high fixed costs, but comparably low variable costs (i.e., extending the institution’s scope to punish also tax evaders does not duplicate the costs of the institution). If at least one participant paid taxes, the punishment institution was established and either imposed a fine on defectors only (institution without second-order punishment) or on defectors and tax evaders (institution with second-order punishment). The fine for defectors (and tax evaders) was set to € 1.00 for each offense. Subjects were informed about whether someone paid taxes before they had to decide whether they want to contribute € 0.50 to a common pool. Total contributions to the pool were multiplied by 3.1 and redistributed to all group participants. See SI Text for further details.

(institution with second-order punishment), respectively. These parameters reflect our assumption that a punishment institution comes with high fixed costs, but comparably low variable costs (i.e., extending the institution’s scope to punish also tax evaders does not duplicate the costs of the institution). If at least one participant paid taxes, the punishment institution was established and either imposed a fine on defectors only (institution without second-order punishment) or on defectors and tax evaders (institution with second-order punishment). The fine for defectors (and tax evaders) was set to € 1.00 for each offense. Subjects were informed about whether someone paid taxes before they had to decide whether they want to contribute € 0.50 to a common pool. Total contributions to the pool were multiplied by 3.1 and redistributed to all group participants. See SI Text for further details.

Theoretical Predictions.

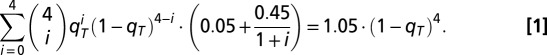

To illustrate the possible strategic considerations of the players, let us calculate the symmetric subgame perfect equilibria for the one-shot public good game. (i) Without second-order punishment, the decision to pay taxes becomes a volunteer’s dilemma (41–43): subjects benefit from the presence of a punishment authority, but they want others to pay the taxes. The symmetric solution to this dilemma is to pay taxes with a certain probability  . This probability can be calculated by comparing the expected cost of paying taxes with the expected loss to be in a group where no one pays taxes (and hence no one cooperates)

. This probability can be calculated by comparing the expected cost of paying taxes with the expected loss to be in a group where no one pays taxes (and hence no one cooperates)

|

Solving this equation leads to the prediction that all players participate in the game, pay taxes with probability  , and contribute in case there was at least someone who paid taxes. In this equilibrium, players earn on average € 0.73 per round. (ii) With second-order punishment, payoff dominance suggests that players participate in the game, pay taxes, and contribute to the common pool. This equilibrium results in an expected payoff of € 0.90. Therefore, independent of the voting procedure, equilibrium payoffs are higher under second-order punishment. These static predictions are also confirmed by a dynamic learning model (SI Text).

, and contribute in case there was at least someone who paid taxes. In this equilibrium, players earn on average € 0.73 per round. (ii) With second-order punishment, payoff dominance suggests that players participate in the game, pay taxes, and contribute to the common pool. This equilibrium results in an expected payoff of € 0.90. Therefore, independent of the voting procedure, equilibrium payoffs are higher under second-order punishment. These static predictions are also confirmed by a dynamic learning model (SI Text).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Abou Chakra and two anonymous referees for insightful comments. We thank K. Hagel and H. Brendelberger for support performing the experiment and the 125 students for their participation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1315273111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Olson M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardin G. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 1968;162(3859):1243–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamagishi T. The provision of a sanctioning system as a public good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(1):110–116. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrom E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Gorman R, Henrich J, Van Vugt M. Constraining free riding in public goods games: designated solitary punishers can sustain human cooperation. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276(1655):323–329. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinker S. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. New York: Penguin Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki T, Brännström Å, Dieckmann U, Sigmund K. The take-it-or-leave-it option allows small penalties to overcome social dilemmas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(4):1165–1169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115219109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler JH. Human cooperation: Second-order free-riding problem solved? Nature. 2005;437(7058):E8. doi: 10.1038/nature04201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigmund K. Punish or perish? Retaliation and collaboration among humans. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22(11):593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilbe C, Traulsen A. Emergence of responsible sanctions without second order free riders, antisocial punishment or spite. Sci Rep. 2012;2:458. doi: 10.1038/srep00458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415(6868):137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrich J, et al. Costly punishment across human societies. Science. 2006;312(5781):1767–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1127333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gürerk Ö, Irlenbusch B, Rockenbach B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science. 2006;312(5770):108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1123633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockenbach B, Milinski M. The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature. 2006;444(7120):718–723. doi: 10.1038/nature05229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiyonari T, Barclay P. Free-riding may be thwarted by second-order rewards rather than punishment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:826–842. doi: 10.1037/a0011381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreber A, Rand DG, Fudenberg D, Nowak MA. Winners don’t punish. Nature. 2008;452(7185):348–351. doi: 10.1038/nature06723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann B, Thöni C, Gächter S. Antisocial punishment across societies. Science. 2008;319(5868):1362–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.1153808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nikiforakis N. Punishment and counter-punishment in public good games: Can we really govern ourselves? J Public Econ. 2008;92(1-2):91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehl K, Sommerfeld RD, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ, Milinski M. I dare you to punish me-vendettas in games of cooperation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gächter S, Renner E, Sefton M. The long-run benefits of punishment. Science. 2008;322(5907):1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1164744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guala F. Reciprocity: Weak or strong? What punishment experiments do (and do not) demonstrate. Behav Brain Sci. 2012;35(1):1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X11000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witt U. The emergence of a protective agency and the constitutional dilemma. Constitutional Political Economy. 1992;3:255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigmund K, De Silva H, Traulsen A, Hauert C. Social learning promotes institutions for governing the commons. Nature. 2010;466(7308):861–863. doi: 10.1038/nature09203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perc M. Sustainable institutionalized punishment requires elimination of second-order free-riders. Sci Rep. 2012;2:344. doi: 10.1038/srep00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Traulsen A, Röhl T, Milinski M. An economic experiment reveals that humans prefer pool punishment to maintain the commons. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279(1743):3716–3721. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang B, Li C, De Silva H, Bednarik P, Sigmund K (2013) The evolution of sanctioning institutions: An experimental approach to the social contract. Exper Econ, 10.1007/s10683-013-9367-7.

- 27.Hobbes T. Leviathan. London: Andrew Crooke; 1651. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeckhauser R. Voting systems, honest preferences and Pareto optimality. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1973;67(3):934–946. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldassarri D, Grossman G. Centralized sanctioning and legitimate authority promote cooperation in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(27):11023–11027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105456108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Putterman L, Tyran J, Kamei K. Public goods and voting on formal sanction schemes. J Public Econ. 2011;95(9-10):1213–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledyard JO. In: The Handbook of Experimental Economics. Kagel JH, Roth AE, editors. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cinyabuguma M, Page T, Putterman L. Can second-order punishment deter perverse punishment? Exp Econ. 2006;9(3):265–279. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axelrod R. An evolutionary approach to norms. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1986;80(4):1095–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colman AM. The puzzle of cooperation. Nature. 2006;440(7085):744–745. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchanan JM, Congleton RD. Politics by Principle, Not Interest. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosfeld M, Okada A, Riedl A. Institution formation in public goods games. Am Econ Rev. 2009;99(4):1335–1355. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schoenmakers S (2013) Pool-punishment and opportunistic cooperation in voluntary and compulsory games. An evolutionary game theory model. MS thesis (Univ of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany)

- 38.Yamagishi T, Takahashi N. In: Social Dilemmas and Cooperation. Schulz U, Albers W, Mueller U, editors. Berlin: Springer; 1994. pp. 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S. Coordinated punishment of defectors sustains cooperation and can proliferate when rare. Science. 2010;328(5978):617–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1183665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dercole F, De Carli M, Della Rossa F, Papadopoulos AV. Overpunishing is not necessary to fix cooperation in voluntary public goods games. J Theor Biol. 2013;326:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diekmann A. Volunteer’s dilemma. J Conflict Resolut. 1985;29(4):605–610. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raihani NJ, Bshary R. The evolution of punishment in n-player public goods games: a volunteer’s dilemma. Evolution. 2011;65(10):2725–2728. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Przepiorka W, Diekmann A. Individual heterogeneity and costly punishment: A volunteer’s dilemma. Proc Biol Sci. 2013;280(1759):20130247. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.