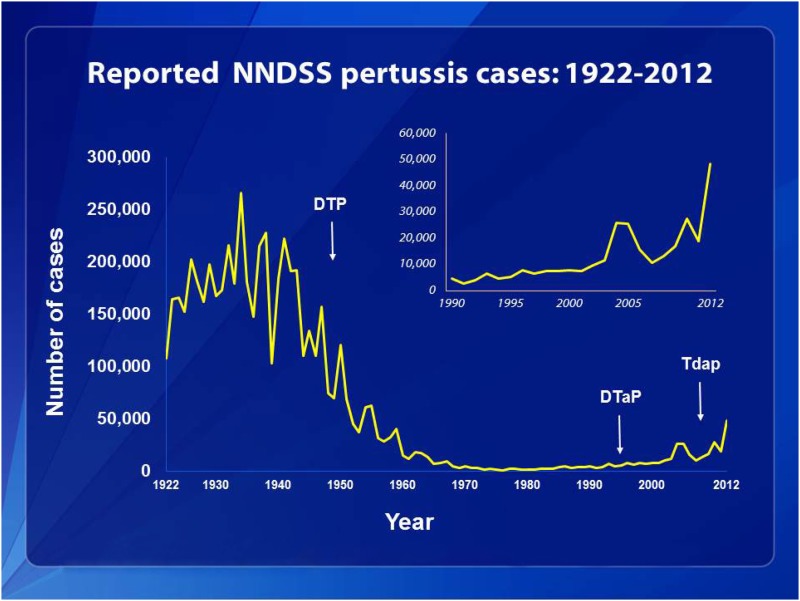

The article by Warfel et al. in PNAS is noteworthy (1) because it shows that in nonhuman primate pertussis challenge models, acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but are ineffective in preventing infection and transmission to other animals. This highly relevant model sheds light on reasons that we are experiencing an outbreak of pertussis disease in the United States and other developed countries (2). Vaccination rates for DTaP (acellular pertussis vaccine combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids) are nearly 90%, but pertussis remains the most common vaccine-preventable disease in the United States (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nis/tables/12/tab07_13mo_iap_2012.pdf). In 2012, rates of pertussis disease in the United States were higher than in any previous year since vaccines were first implemented (Fig. 1) (www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html).

Fig. 1.

This graph illustrates the number of pertussis cases reported to the CDC from 1922 to 2012. Following the introduction of pertussis vaccines in the 1940s when case counts frequently exceeded 100,000 cases per year, reports declined dramatically to fewer than 10,000 by 1965. During the 1980s pertussis reports began increasing gradually and by 2012 more than 48,000 cases were reported nationwide, the most since 1955. Source: CDC, National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System and Supplemental Pertussis Surveillance System and 1922–1949, passive reports to the Public Health Service.

Since the late 1940s, pertussis vaccines prepared by formalin inactivation of “whole” Bordetella pertussis organisms combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids (DTwP) have been recommended for infants (3). DTwP vaccines were associated with a marked decline in pertussis, reaching a nadir in 1976. However, parental concern for reactions, particularly high fever and febrile seizures, after DTwP reduced vaccine uptake. Litigation against vaccine manufacturers for adverse neurologic events forced several to stop DTwP production. Adverse events were temporally associated with immunization, but not shown to be causally related. Finally, reports of reduced DTwP effectiveness, coupled with increasing safety concerns, resulted in the complete cessation of pertussis vaccination programs in Japan and Sweden. Soon pertussis outbreaks were reported in unimmunized children.

Intensive research resulted in the identification of several proteins produced by the B. pertussis organism (3), including: pertussis toxin (PT), an A-B bacterial toxin believed to be associated with many of the biologic activities of the organism, and three surface attachment proteins, filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin, (PRN), and two fimbriae proteins (FIM). Because of its central role in pathogenesis, PT alone or in combination with one or more antigens was included in the “acellular vaccines.” A large National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded clinical trial compared the safety and immunogenicity of 13 DTaP vaccines, with 2 DTwP vaccines in over 2,000 infants (4, 5). Serologic responses revealed that each of the DTaP vaccines was highly immunogenic, generating comparable or higher immune responses than those seen after DTwP (4). In addition, each of the DTaP vaccines was associated with significantly fewer local and systemic reactions than after DTwP vaccines (5). At the completion of this trial, several DTaP vaccines were selected for inclusion in vaccine efficacy studies in Sweden and Italy, using laboratory-confirmed pertussis disease of 21-d duration as the endpoint (6, 7). Just before the initiation of these efficacy trials, the two DTwP vaccines included in the previous NIH-funded studies were replaced by a different DTwP product, subsequently shown to stimulate much lower antibody titers to PT (8).

The efficacy trials demonstrated that multicomponent DTaP vaccines were 85% efficacious in both Sweden and Italy; in contrast, DTwP was only 36% efficacious in Italy and 48% efficacious in Sweden (6, 7). Several other industry-funded efficacy trials conducted in Europe and Africa demonstrated high vaccine efficacy for both DTaP and DTwP products (3). With the improved safety of DTaP vaccines and established efficacy, DTaP vaccines replaced DTwP vaccines in the United States in 1997 and many other developed countries soon after. Studies in Sweden and Italy demonstrated durable protection against pertussis for 5–7 y after a primary series at 2, 4, and 6 mo of age (9, 10). The replacement of the DTwP with less reactogenic DTaP was regarded as a triumph and restored parental confidence in pertussis-containing vaccines.

The availability of serologic methods to measure immune responses to DTaP vaccines were used to document that 12–26% of cough episodes lasting over 14 d in adolescents and adults were confirmed to be pertussis (11). The role of adolescents and adults in disease transmission was also demonstrated. Thus, in 2006 an additional booster dose of reduced acellular pertussis vaccine combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid (Tdap) was recommended for all adolescents; uptake now approaches 80% (12).

In 2010 a large pertussis outbreak was reported in California. Over 9,000 cases were diagnosed, the highest number since 1947, including 10 infant deaths (13). A substantial burden of disease occurred in 7- to 10-y-old children, fully immunized with five doses of DTaP. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports demonstrated vaccine efficacy of 98% for 1 y after the fifth dose of DTaP but only 71% 5 y later (13). Thus, waning immunity was believed to be responsible for the large burden of pertussis disease in the 7- to 10-y age group. Additional reports from the California outbreak supported waning immunity and demonstrated that children primed with DTwP vaccines had more lasting immunity than those primed with DTaP (14, 15). Similar data were reported from Australia, where DTaP vaccines also replaced DTwP vaccines (16).

Serologic studies conducted comparing humoral immune responses to DTwP and DTaP in infants showed comparable or higher titers in those immunized with DTaP (5). Similar serologic responses were reported by Warfel et al. in nonhuman primates, suggesting that the differences noted in colonization after pertussis challenge in the baboons vaccinated with DTaP or DTwP did not correlate with differences in antibody responses (1). Earlier studies in humans clearly demonstrated that DTaP vaccines stimulated T-helper 2 (Th2) responses, whereas natural infection and DTwP vaccines stimulated Th1 responses (17). These findings were also confirmed in the nonhuman primate studies, showing that T-cell responses to DTaP were mismatched to those seen after both natural infection and DTwP vaccine (1).

Earlier investigators used mouse models of respiratory challenge with pertussis to gain insight into the innate and adaptive immune responses needed to prevent pertussis colonization and disease (18). Mice infected with wild-type pertussis or vaccinated with

In 2012, rates of pertussis disease in the United States were higher than in any previous year since vaccines were first implemented.

whole-cell pertussis vaccines developed both Th17 and Th1 immune responses, whereas mice immunized with acellular vaccines did not. Warfel et al. replicated these findings in the nonhuman primate model (1). The potential role of a Th17 response is intriguing because it appears to be particularly important in controlling extracellular bacterial infections at the mucosal surface. Recent reports in children after booster DTaP doses have shown poor Th17 recall responses in acellular-primed but not whole-cell–primed children (19).

The studies of Warfel et al. suggest that DTaP vaccines are much less effective at preventing transmission than natural disease and are substantially less effective than DTwP vaccines in preventing transmission (1). Like the nonhuman primates, it is highly likely that asymptomatic transmission of B. pertussis to other humans also occurs in DTaP-immunized humans and that this transmission fuels pertussis outbreaks. The other remarkable finding in the Warfel et al. study is the role of both Th1 and Th17 cells in the immune response to natural infection and DTwP vaccine and only the Th2 immune responses after DTaP vaccines.

What ways can we modify pertussis vaccinations to improve effectiveness (20)? One option would be the restoration of DTwP vaccines; however, in the current climate of vaccine hesitancy it is unlikely that parents would tolerate the increased reactions associated with the whole-cell product. Additionally, as shown in the initial NIH-funded vaccine efficacy studies, not all DTwP vaccines are highly efficacious. Another alternative would be to add other B. pertussis antigens to DTaP, such as adenylate cyclase or BrkA. A third alternative would be to include an adjuvant that would stimulate a more Th1 or Th17 response rather than the preferential Th2 response currently seen with DTaP. Finally, a recently developed live-attenuated intranasal B. pertussis vaccine could be used to generate local immunity and reduce transmission. The potential for evaluating these alternative approaches in the nonhuman primate model is extremely attractive.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 787.

References

- 1.Warfel JM, Zimmerman LI, Merkel TJ. Acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but fail to prevent infection and transmission in a nonhuman primate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:787–792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314688110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warfel JM, Beren J, Kelly VK, Lee G, Merkel TJ. Nonhuman primate model of pertussis. Infect Immun. 2012;80(4):1530–1536. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06310-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards KM, Decker MD. Pertussis vaccines. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. 6th Ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 447–492. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards KM, et al. Comparison of 13 acellular pertussis vaccines: Overview and serologic response. Pediatrics. 1995;96(3 Pt 2):548–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker MD, et al. Comparison of 13 acellular pertussis vaccines: Adverse reactions. Pediatrics. 1995;96(3 Pt 2):557–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafsson L, Hallander HO, Olin P, Reizenstein E, Storsaeter J. A controlled trial of a two-component acellular, a five-component acellular, and a whole-cell pertussis vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(6):349–355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greco D, et al. Progetto Pertosse Working Group A controlled trial of two acellular vaccines and one whole-cell vaccine against pertussis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(6):341–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuliano M, et al. Antibody responses and persistence in the two years after immunization with two acellular vaccines and one whole-cell vaccine against pertussis. J Pediatr. 1998;132(6):983–988. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafsson L, Hessel L, Storsaeter J, Olin P. Long-term follow-up of Swedish children vaccinated with acellular pertussis vaccines at 3, 5, and 12 months of age indicates the need for a booster dose at 5 to 7 years of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):978–984. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salmaso S, et al. Stage III Working Group Sustained efficacy during the first 6 years of life of 3-component acellular pertussis vaccines administered in infancy: The Italian experience. Pediatrics. 2001;108(5):E81. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senzilet LD, et al. Sentinel Health Unit Surveillance System Pertussis Working Group Pertussis is a frequent cause of prolonged cough illness in adults and adolescents. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(12):1691–1697. doi: 10.1086/320754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2012. August 30, 2013, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(34):685–693. Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6234a1.htm. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 13.Misegades LK, et al. Association of childhood pertussis with receipt of 5 doses of pertussis vaccine by time since last vaccine dose, California, 2010. JAMA. 2012;308(20):2126–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witt MA, Katz PH, Witt DJ. Unexpectedly limited durability of immunity following acellular pertussis vaccination in preadolescents in a North American outbreak. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(12):1730–1735. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein NP, Bartlett J, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Fireman B, Baxter R. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1012–1019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheridan SL, Ware RS, Grimwood K, Lambert SB. Number and order of whole cell pertussis vaccines in infancy and disease protection. JAMA. 2012;308(5):454–456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ausiello CM, Urbani F, la Sala A, Lande R, Cassone A. Vaccine- and antigen-dependent type 1 and type 2 cytokine induction after primary vaccination of infants with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect Immun. 1997;65(6):2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2168-2174.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross PJ, et al. Relative contribution of Th1 and Th17 cells in adaptive immunity to Bordetella pertussis: Towards the rational design of an improved acellular pertussis vaccine. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(4):e1003264. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schure RM, et al. T-cell responses before and after the fifth consecutive acellular pertussis vaccination in 4-year-old Dutch children. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19(11):1879–1886. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00277-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Libster R, Edwards KM. Re-emergence of pertussis: What are the solutions? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11(11):1331–1346. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]