Abstract

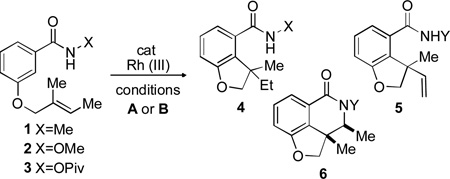

Three different Rh(III)-catalyzed reaction pathways of a wide variety of tethered alkenes can be accessed through the change of the amide directing group. This provides an efficient route to a myriad of complex polycyclic products, many containing newly-formed all-carbon quaternary centers. Amidoarylations can highly diastereoselectively deliver products with up to three contiguous stereocenters.

Keywords: Rhodium catalysis, hydroarylation, amidoarylation, dehydrogenative Heck-type reaction, C-H activation

Rh(III) catalysis has enabled a vast number of transformations through C-H activation. Many examples exist of functionalization of arenes at the ortho position to a directing group eliminating the need for prior activation at that position, emerging as a powerful strategy to form sp2-sp3 C-C bonds from aryl and alkenyl C-H bonds.[1]

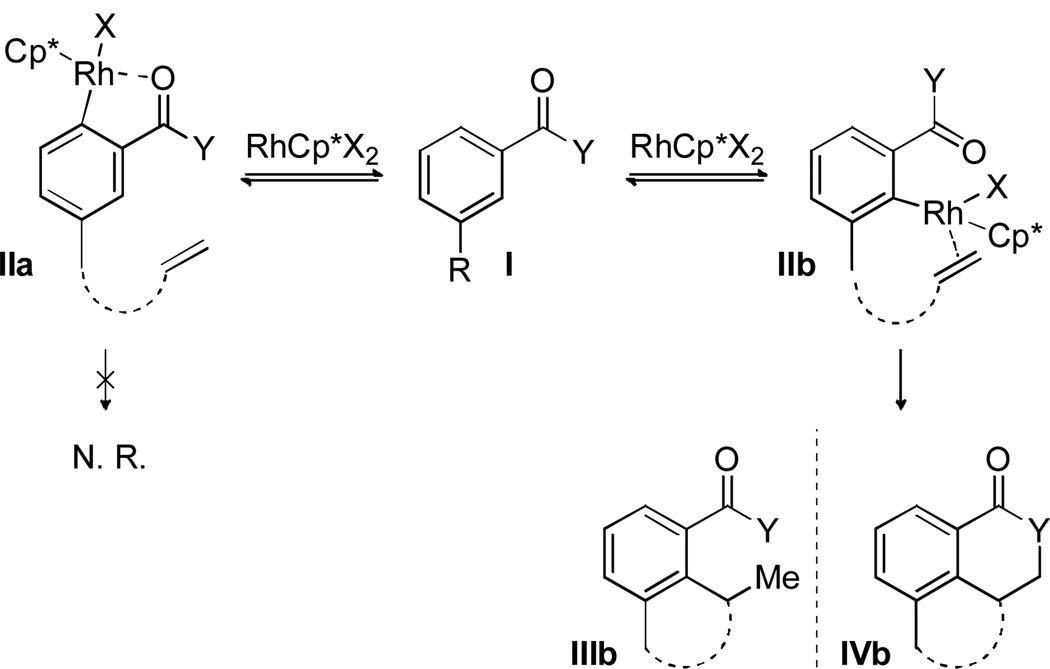

The use of simple alkenes as partners in the C-H/N-H activation of benzamides has been demonstrated previously,[2] and in a few cases has been rendered enantioselective.[3] Nevertheless, most cases are limited to functionalized alkenes: styrenes and acrylates undergo regioselective insertion (5:1 to 20:1) whereas terminal alkenes perform poorly (~1–2:1).[4] The situation is further exacerbated by the use of unsymmetrical benzamide partners: 3-substituted benzamides have two distinct C-H bonds ortho to the directing group leading to a pair of potential rhodacycles (IIa and IIb, Scheme 1) and give mixtures of products sometimes dominated by sterics and other times by electronics.[5]

Scheme 1.

Regioselective C-H activation.

In order to obtain understanding about these issues of regioselectivity, we sought to use simple alkenes tethered to the benzamide system through the meta position.[6] While this has the obvious disadvantage of a tethering strategy, we hoped to gain insights into the reaction and use more complex stereochemically defined internal alkenes to arrive at products IIIb and IVB (Scheme 1). In particular, the ability to use 1,1-disubstituted and trisubstituted alkenes could lead to synthetically challenging all-carbon quaternary stereocenter-containing compounds that have not been accessed through previous methods.[7] We have previously demonstrated that Cp*Rh(III) undergoes reversible C-H activation in the absence of alkyne[8] and we thus felt that even if the more sterically accessible C-H bond was first to be activated (IIA, Scheme 1), it should not undergo reaction because of the lack of an appropriate coupling partner. Herein we disclose our results.

Subjection of a simple E-trisubstituted alkene tethered to the 3-position of methyl benzamide to cationic Rh(III) catalyst (condition A, entry 1, Table 1) and stoichiometric pivalic acid in DCE at 80 °C led to full conversion to the hydroarylation product 4.[9] The subjection of the corresponding N-OMe amide (entry 2) to the same reaction conditions provided a 71:29 mixture of the hydroarylation product 4 and the dehydrogenative Heck-type (DH) product 5.[10] Reaction of the N-OPiv amide yielded the amidoarylation product 6 along with hydrolysis of the starting material. Ultimately, conducting the reaction of amides 2 and 3 under basic conditions resulted in products 5 and 6 selectively at ambient temperature.

Table 1.

Initial Optimization of Hydroarylation Conditions[a]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | X | Y | condition | 4:5:6 | Conv.[b] |

| 1 | Me | Me | A, 17 h | 100:0:0 | 100 |

| 2 | OMe | H | A, 17 h | 71:29:0 | 53 |

| 3 | OPiv | H | A, 17 h | 0:0:100 | 61[c] |

| 4 | OMe | H | B, 2 h | 0:100:0 | 100 |

| 5 | OPiv | H | B, 12 h | 0:22:78 | 100 |

Reactions conducted on 0.1 mmol scale. A: [RhCp*(MeCN)3](SbF6)2 (1 mol%), 1 equiv. tBuCO2H, 1,2-dichloroethane (0.2 M), 80 °C; B: [RhCp*Cl2]2 (2.5 mol%), CsOAc (2 equiv.), MeOH (0.2 M), rt

Conversion determined by 1H NMR.

Starting material hydrolysis also observed.

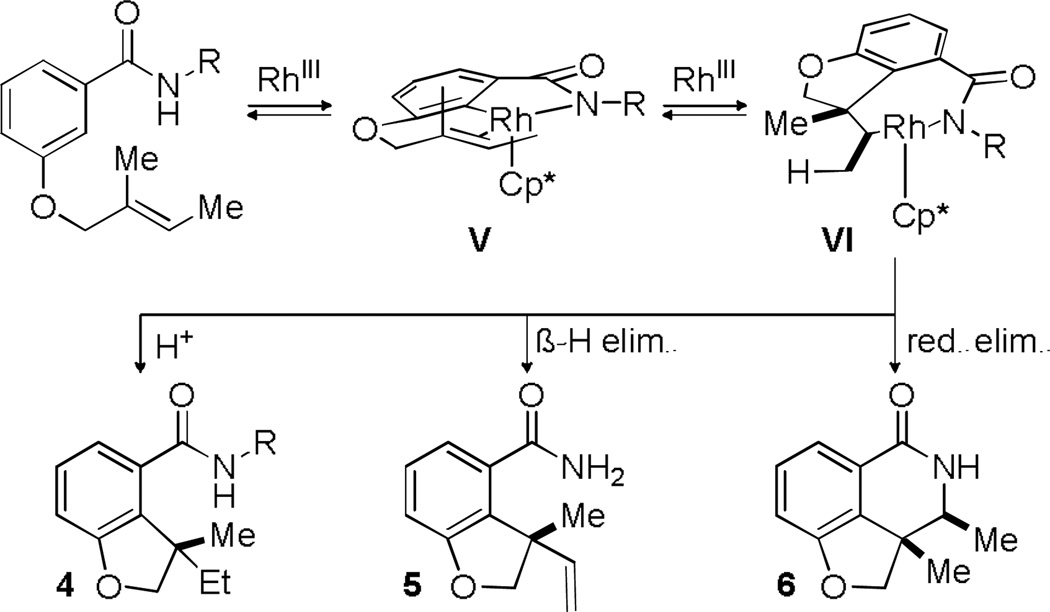

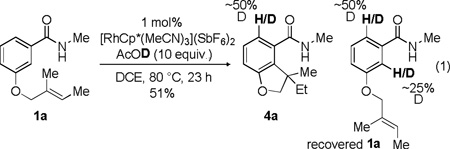

Mechanistically, this reaction may proceed through a C-H activation event and addition of the aryl rhodium species across the alkene to provide the 7-membered metallacycle VI (Scheme 2). Protonation could then lead to the hydroarylation product 4. This common metallacycle could also proceed to a reductive elimination pathway (6) or a β-hydride elimination pathway (5) with reduction of the metal. Validation of our hypothesis that the Rh catalyst samples both ortho positions on the benzamide came from a deuterium labelling experiment. Subjection of 1a to the hydroarylation conditions in the presence of AcOD resulted in deuterium incorporation at the ortho position in product 4a but also in both ortho positions in recovered starting material (eq 1).

|

(1) |

Scheme 2.

Plausible Mechanistic Pathways

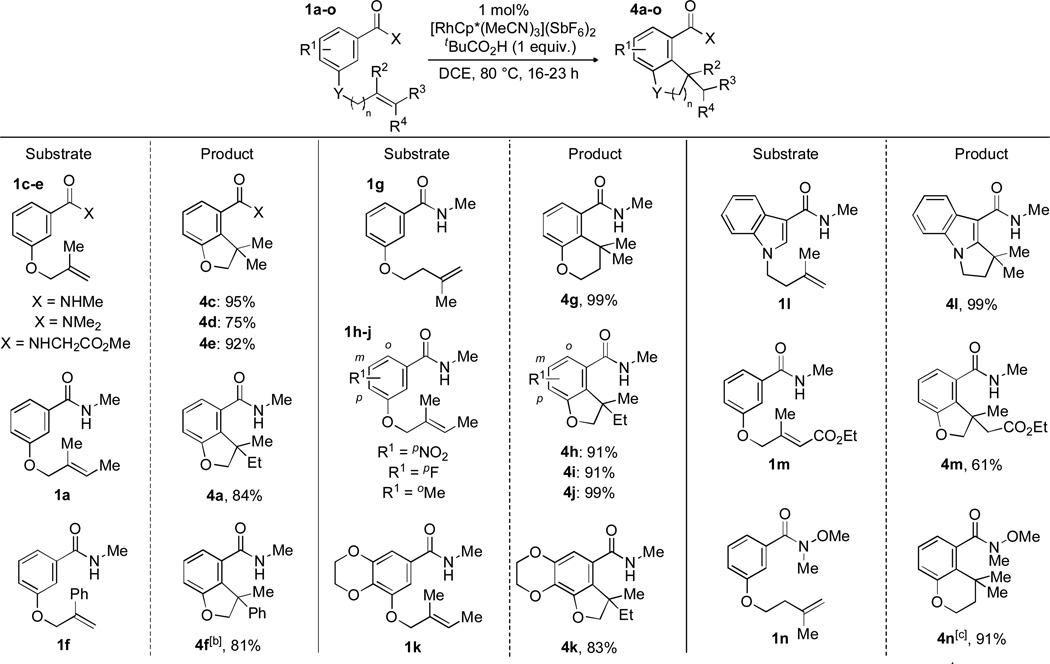

We were intrigued by the ability to deliver three distinct products simply by choice of amide substituent and sought to delineate the scope of each transformation. Using the optimal conditions for hydroarylation,[11,12] the amide portion of the tethered alkene was varied to investigate its impact (Scheme 3). An N,N-dimethylamide was used to provide cyclized product 4d in 75% yield. A glycine amide led to product 4e in excellent yield (92%). Changing the directing group to an ester was detrimental as only a small amount of conversion to product was observed by NMR under the standard conditions.

Scheme 3.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Hydroarylation. [a] Reaction conditions: 1 mol% [RhCp*(MeCN)3](SbF6), 1 equiv. tBuCO2H, 1,2-dichloroethane (0.2 M), 80 °C, 16–23 h. [b] 5 mol% [RhCp*(MeCN)3](SbF6) used. [c] 2.5 mol% [RhCp*(MeCN)3](SbF6) used.

A wide variety of tethered alkenes were found to undergo the desired cyclization. Modification of the alkene was tolerated as several 1,1-di- and trisubstituted alkenes[13] were converted to the cyclized products. In addition to 5-membered rings, 6-membered rings (4g, 4n) could be formed. Electronic and steric modification of the aryl group was also tolerated. Electron-deficient p-nitro and p-flouro substrates each gave the corresponding bicycle (4h and 4i, respectively) in 91% yield. Ortho-substitution of a methyl group also led to good yield (4j, 99%). An electron-rich dioxanyl substrate was converted to product 4k in 83% yield. An alkene tethered to an indole cleanly converted to product (4l, 99%). An acrylate system reacted to give the resulting ester 4m in 61% yield. A Weinreb amide is also tolerated delivering the hydroarylation product 4n in 91% yield.[14]

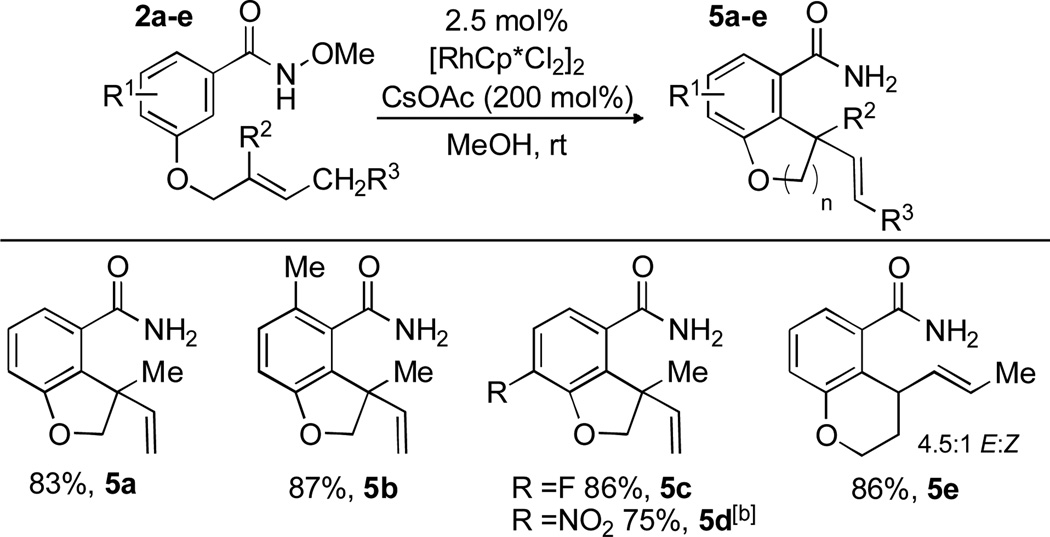

The β-H elimination/DH pathway produces another useful product with an all carbon quarternary stereocenter. Direct intermolecular C-H allylations have been demonstrated with a variety of metals but are limited by the necessity to use electron-deficient arenes or harsh conditions. More recently, allenes (Ir[15] and Rh(III)-catalyzed[16]) and allyl carbonates (Rh(III)-catalyzed[17])have been used in directed C-H allylations. In contrast to the previous examples that use a variety of leaving groups on the allyl fragment, this pathway provides the allylated product from an allyl substrate by an oxidative pathway.

We briefly explored the scope of this transformation (Scheme 4). With the necessity to use an alkene with an available β-hydride, we modified the aryl portion with tri-substituted alkenes. Three additional substrates were shown to undergo the DH reaction in good yield (75–86%). An E-1,1-disubstituted alkene also underwent the DH reaction to form the dihydrobenzopyran product 5e in good yield and moderate E:Z selectivity (86%, 4.5:1).

Scheme 4.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Intramolecular DH-type reactions. [a] Reaction conditions: 2.5 mol% [RhCp*Cl2]2, 2 equiv. CsOAc, MeOH (0.2 M), 1–2 h. [b] 20 h reaction time

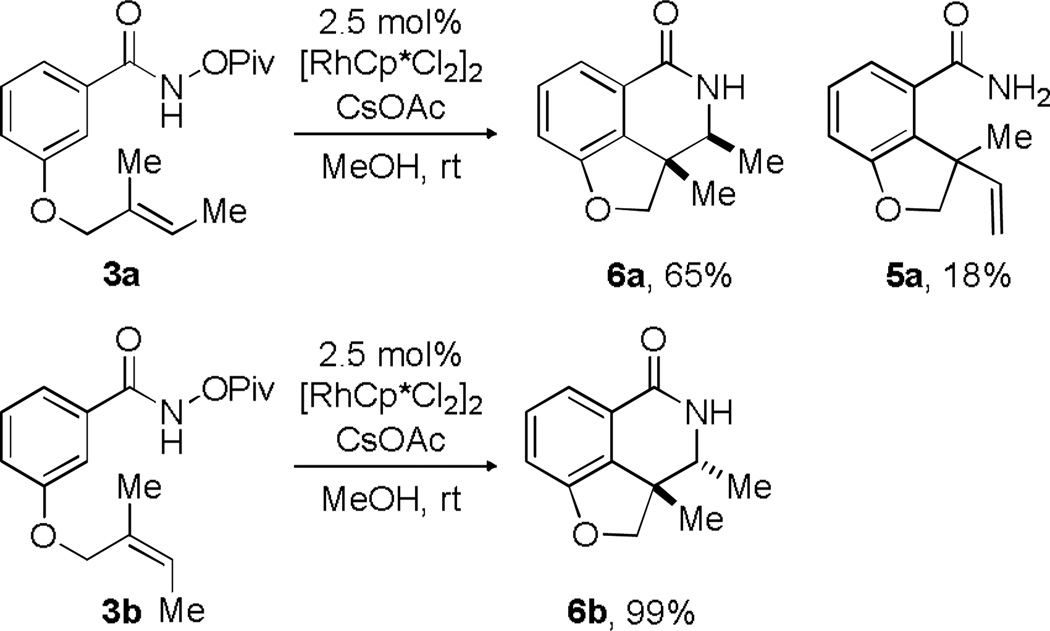

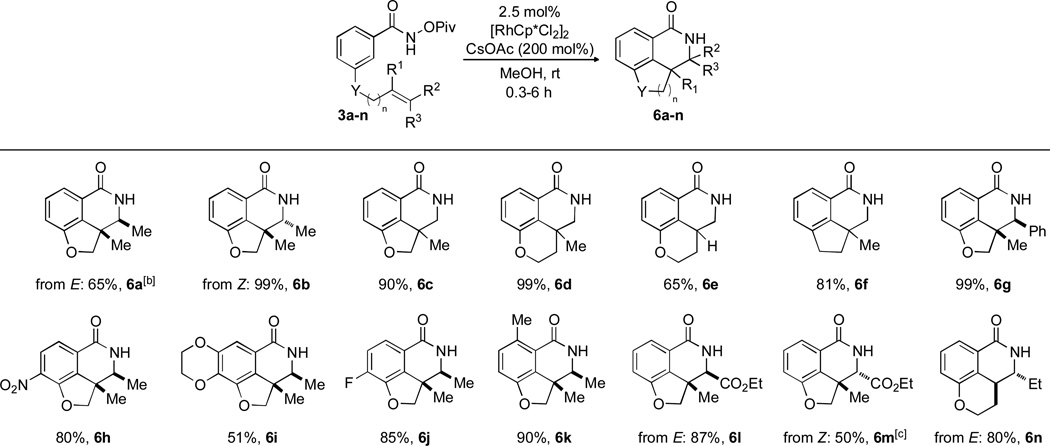

The third pathway identified in this work, the amidoarylation reaction, allowed us to examine the impact of olefin geometry on the reaction. When the (E)-olefin 3a (Scheme 5) was subjected to the reaction conditions, a single isomer of desired insertion product was isolated in 65% yield with a small amount of byproduct 5a (resulting from β-H elimination) isolated in 18% yield. Subjection of the (Z)-alkene 3b to the reaction conditions provided the opposite diastereomer of the insertion product (6b) exclusively (99% yield). Importantly, starting olefin geometry is faithfully relayed into product stereochemistry.

Scheme 5.

Amidoarylations of E- and Z- Olefins. [a] Reaction conditions: 2.5 mol% [RhCp*Cl2]2, 2 equiv. CsOAc, MeOH (0.2 M)

An extensive scope was demonstrated for this reaction in Scheme 6. This reaction was found to tolerate mono-, 1,1-di, and tri-substituted olefins. An all carbon-tethered alkene and a phenyl-substituted alkene provided product in good yield (6f, 81% and 6g, 99%, respectively). Electron-poor (6h and 6j), -rich (6i), and ortho-substituted (6k) aryl products were prepared. E and Z tethered α,β-unsaturated esters each successfully inserted to give a single diastereomer (E giving 6l, 87%, and Z giving 6m, 50%). An E-1,1-disubstituted alkene cyclized to solely give the trans product 6n in good yield.

Scheme 6.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Amidoarylations. [a] Reaction conditions: see Scheme 5, 0.3–6 h reaction time. [b] 18 h reaction time. [c] 48 h reaction time

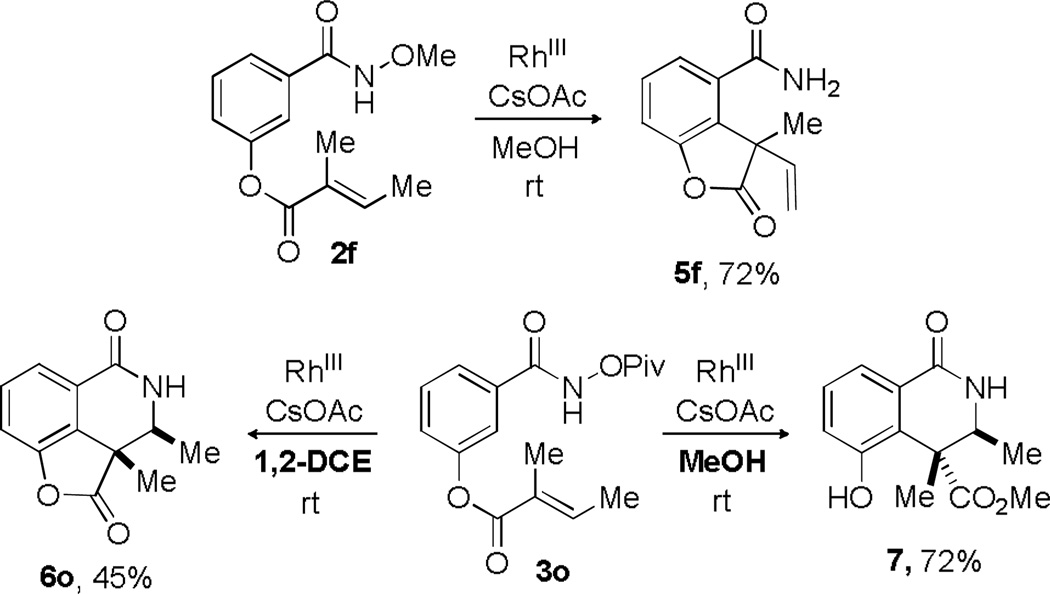

In an attempt to provide access to a broader range of products, an ester-tethered substrate was subjected to the optimal reaction conditions. Cyclization of N-methoxy amide 2f (Scheme 7) proceeded smoothly to provide the cleavable lactone product 5f in 72% yield. In contrast, reaction of the corresponding N-pivaloxy amide 3o resulted in the formation of methanolysis product 7. This mild lactone cleavage is likely an indication of considerable strain within this tricyclic system and other similar systems formed in Scheme 6. Alternatively, use of a non-nucleophilic solvent (1,2-dichloroethane) allowed the desired lactone 6o to be synthesized and isolated in modest yield (45%).

Scheme 7.

DH and Amidoarylation of a Cleavable Ester Tether.[a] Reaction conditions: 2.5 mol% [RhCp*Cl2]2, 2 equiv. CsOAc, MeOH or 1,2-dichloroethane (0.2 M), 0.5–18 h

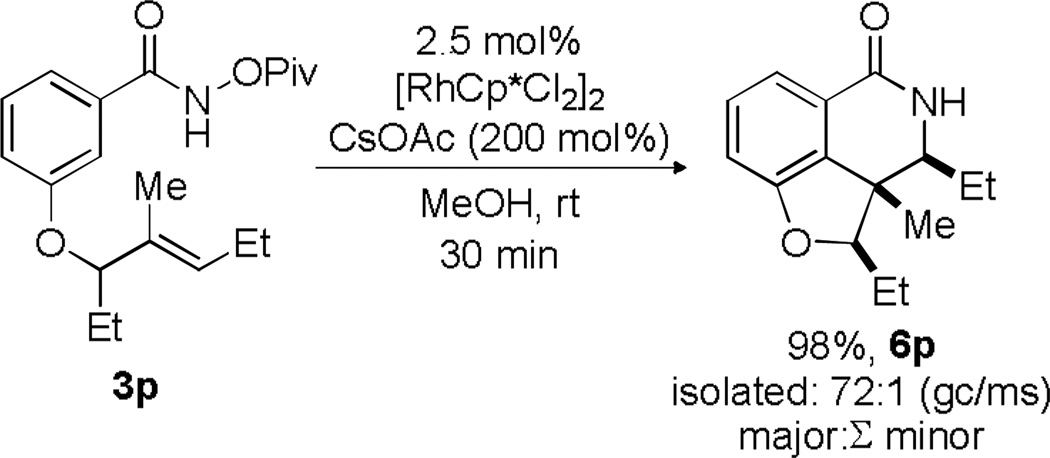

To further demonstrate the utility of this reaction, we explored the effect of a pre-existing stereocenter on these transformations. It seemed likely that reactivity could be directed to one face of the olefin based on the sterics provided by a stereocenter. This would potentially lead to a product with three contiguous stereocenters in a highly controlled fashion. Substitution of an alkyl substituent alpha to the tethered alkene was well tolerated under the standard conditions as the product 6p was obtained in 98% yield (Scheme 8). Furthermore, this reaction was found to be highly diastereoselective as the compound was determined to be >20:1 dr by 1H NMR and 72:1 by GC/MS. A series of NOESY experiments[18] indicated a syn,syn relationship between the three alkyl groups.

Scheme 8.

Diastereoselective Cyclization. [a] Reaction conditions: see Scheme 5.

In summary, we have found three distinct Rh(III)-catalyzed reaction pathways of tethered olefin-containing benzamides. Hydroarylation, amidoarylation, and dehydrogenative Heck-type products can be access based on the type of amide substrate used. A wide variety of tethered alkenes can cyclise to make the 5 or 6 membered products in good to excellent yields. Furthermore, high diastereoselectivity has been observed in the amidoarylation reaction of a substrate containing a pre-existing stereocenter. Efforts to further expand the scope and impart enantioselectivity to this reaction are underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank NIGMS (GM80442) for support and Johnson Matthey for a generous gift of Rh salts.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Song G, Wang F, Li X. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3651. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15281a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Satoh T, Miura M. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:11212. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Guimond N, Gorelsky SI, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6449. doi: 10.1021/ja201143v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rakshit S, Grohmann C, Besset T, Glorius F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2350. doi: 10.1021/ja109676d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Patureau FW, Besset T, Glorius F. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:1096. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1064. [Google Scholar]; d) Wang F, Song G, Li X. Org. Lett. 2010;12:5430. doi: 10.1021/ol102241f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Hyster TK, Knörr L, Ward TR, Rovis T. Science. 2012;338:500. doi: 10.1126/science.1226132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ye B, Cramer N. Science. 2012;338:504. doi: 10.1126/science.1226938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ye B, Cramer N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:636. doi: 10.1021/ja311956k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.See ref. 2a.

- 5.a) see ref 2d. For an example with Ru(II), see: Li B, Ma J, Wang N, Feng H, Xu S, Wang B. Org. Lett. 2012;14:736. doi: 10.1021/ol2032575. For an example with allenes, see: Wang H, Glorius F. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:7430. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201273. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:7318. For examples involving Ru(II) catalyst and alkynes, see: Li B, Feng H, Xu S, Wang B. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:12573. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102445. Ackermann L, Lygin AV, Hofmann N. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:6503. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101943. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6379. Ackermann L, Fenner S. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6548. doi: 10.1021/ol202861k.

- 6.Intramolecular Rh(I)-catalyzed examples: Thalji RK, Ahrendt KA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9692. doi: 10.1021/ja016642j. Ahrendt KA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1301. doi: 10.1021/ol034228d. Thalji RK, Ellman JA, Bergman RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7192. doi: 10.1021/ja0394986. Thalji RK, Ahrendt KA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6775. doi: 10.1021/jo050757e. O'Malley SJ, Tan KL, Watzke A, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13496. doi: 10.1021/ja052680h. Watzke A, Wilson RM, O'Malley SJ, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Synlett. 2007:2383. Harada H, Thalji RK, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:6772. doi: 10.1021/jo801098z. For an intramolecular Pd-catalyzed hydroarylation of indoles, see: Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9578. doi: 10.1021/ja035054y. For an intramolecular Co-catalyzed hydroarylation of indoles, see: Ding Z, Yoshikai N. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:8736. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8574. For a different tethering strategy for intramolecular amidoarylation of alkynes with Rh(III), see: Xu X, Liu Y, Park C-M. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:9506. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204970. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9372.

- 7.a) see ref. 6a–6g. b) For intramolecular examples forming all-carbon quaternary centers limited to indole substrates, see ref. 6h–6i.

- 8.Hyster TK, Rovis T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10565. doi: 10.1021/ja103776u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.No reaction was observed in the absence of [RhCp*(MeCN)3](SbF6)2 or when substituting [RhCp*Cl2]2 for [RhCp*(MeCN)3](SbF6)2.

- 10.This same trend was observed by Glorius with intermolecular olefinations (in contrast to the DH-type reaction observed in this work) and amidoarylations; see ref. 2b.

- 11.For a seminal example, see: Murai S, Kakiuchi F, Sekine S, Tanaka Y, Kamatani A, Sonoda M, Chatani N. Nature. 1993;366:529. Intermolecular Rh(I)-catalyzed examples: Lim S-G, Ahn J-A, Jun C-H. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4687. doi: 10.1021/ol048095n. Jun C-H, Hong J-B, Kim Y-H, Chung K-Y. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:3582. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001002)39:19<3440::aid-anie3440>3.0.co;2-1. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3440.

- 12.Li and Huang have recently demonstrated intermolecular Rh(III)-catalyzed hydroarylations with 2-phenylpyridine and enones and chalcones respectively; see: Yang L, Correia CA, Li C-J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:7176. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05993a. Yang L, Qian B, Huang H. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:9511. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201348.

- 13.Under the same conditions, the reaction of the Z-isomer of 1a provided 4a, but in much lower conversion. Since the same product results from the use of either isomer, the E- trisubstituted olefins were used exclusively.

- 14.Examples of the use of Weinreb amides as directing groups: Yang F, Ackermann L. Org. Lett. 2013;15:718. doi: 10.1021/ol303520h. Wang Y, Li C, Li Y, Yin F, Wang X-S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013;355:1724.

- 15.Zhang YJ, Skucas E, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4248. doi: 10.1021/ol901759t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeng R, Fu C, Ma S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9597. doi: 10.1021/ja303790s. b) see ref. 3c.

- 17.Wang H, Schröder N, Glorius F. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:5495. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:5386. [Google Scholar]

- 18.See supporting information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.