Abstract

The present review describes the current status of synthetic five and six-membered cyclic peroxides such as 1,2-dioxolanes, 1,2,4-trioxolanes (ozonides), 1,2-dioxanes, 1,2-dioxenes, 1,2,4-trioxanes, and 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes. The literature from 2000 onwards is surveyed to provide an update on synthesis of cyclic peroxides. The indicated period of time is, on the whole, characterized by the development of new efficient and scale-up methods for the preparation of these cyclic compounds. It was shown that cyclic peroxides remain unchanged throughout the course of a wide range of fundamental organic reactions. Due to these properties, the molecular structures can be greatly modified to give peroxide ring-retaining products. The chemistry of cyclic peroxides has attracted considerable attention, because these compounds are used in medicine for the design of antimalarial, antihelminthic, and antitumor agents.

Keywords: cyclic peroxides; 1,2-dioxanes; 1,2-dioxenes; 1,2-dioxolanes; ozonides; 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes; 1,2,4-trioxanes; 1,2,4-trioxolanes

Introduction

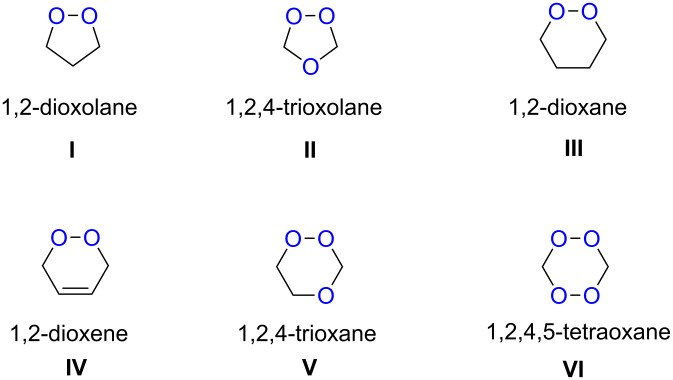

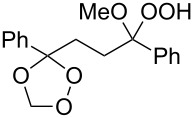

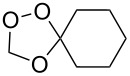

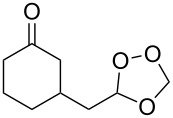

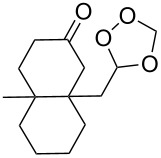

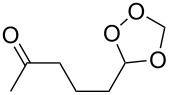

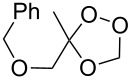

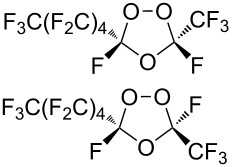

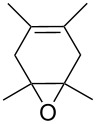

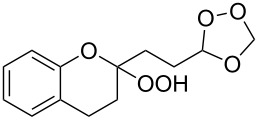

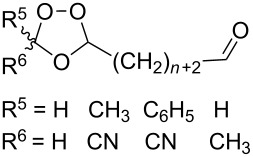

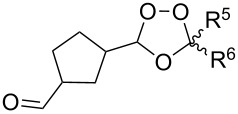

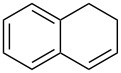

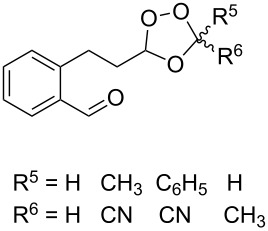

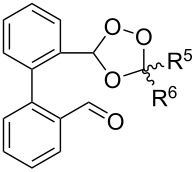

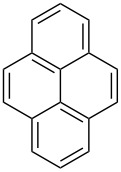

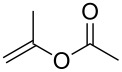

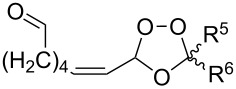

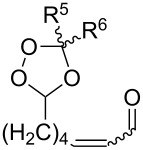

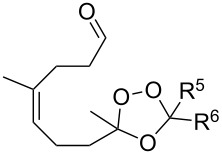

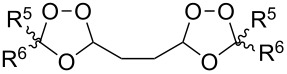

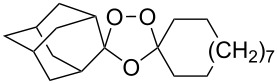

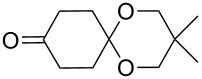

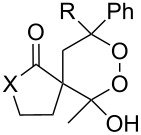

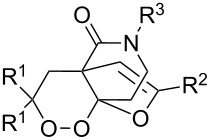

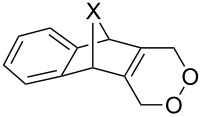

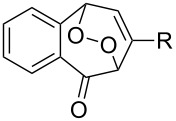

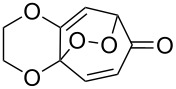

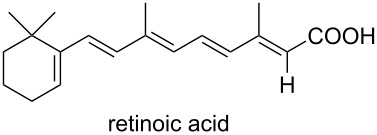

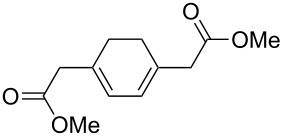

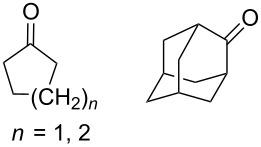

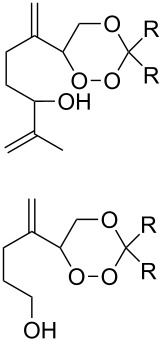

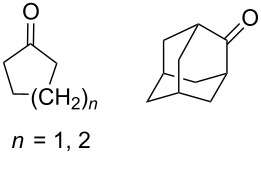

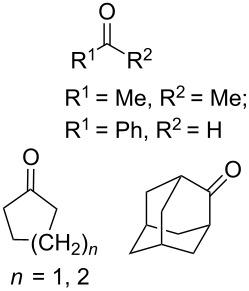

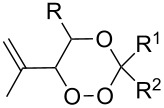

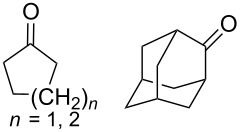

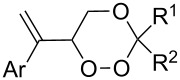

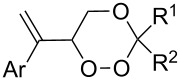

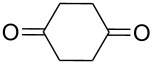

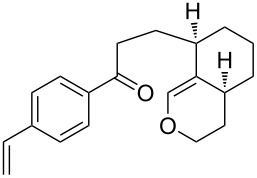

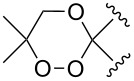

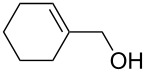

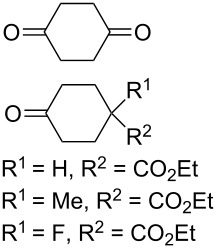

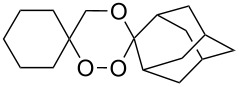

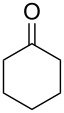

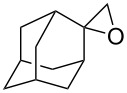

Approaches to the synthesis of five and six-membered cyclic peroxides, such as 1,2-dioxolanes I, 1,2,4-trioxolanes (ozonides) II, 1,2-dioxanes III, 1,2-dioxenes IV, 1,2,4-trioxanes V, and 1,2,4,5-tetraoxanes VI, published from 2000 to present are reviewed. These compounds are widely used in synthetic and medicinal chemistry (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Five and six-membered cyclic peroxides.

In the last decade, two reviews on this rapidly progressing field were published by McCullough and Nojima [1] and Korshin and Bachi [2] covering earlier studies. There are several review articles on medicinal chemistry of peroxides, where the problems of their synthesis are briefly considered. In addition to these reviews other publications dealing with this subject appeared: Tang et al. [3], O’Neill, Posner and colleagues [4–5], Masuyama et al. [6], Van Ornum et al. [7], Jefford [8–9], Dembitsky et al. [10–15], Opsenica and Šolaja [16], Muraleedharan and Avery [17], and other [18–27] including dissertations [28–32].

Reviews published earlier on the chemistry of ozone [33–36] and on the chemistry and biological activity of natural peroxides, and cyclic peroxides [37–46] are closely related to this review. Generally speaking, state-of-the-art approaches to the synthesis of cyclic peroxides are based on three key reagents: oxygen, ozone, and hydrogen peroxide. These reagents and their derivatives are used in the main methods for the introduction of the peroxide group, such as the singlet-oxygen ene reaction with alkenes, the [4 + 2]-cycloaddition of singlet oxygen to dienes, the Mukaiyama–Isayama peroxysilylation of unsaturated compounds, the Kobayashi cyclization, the nucleophilic addition of hydrogen peroxide to carbonyl compounds, the ozonolysis, and reactions with the involvement of peroxycarbenium ions.

Each part of the review deals with a particular class of the above-mentioned peroxides in accordance with an increase in the number of oxygen atoms and the ring size. In the individual sections, the data are arranged mainly according to the common key step in the synthesis of the cyclic peroxides. Examples of the synthesis of peroxide derivatives via modifications of functional groups, with the peroxide bond remaining unbroken, are given in the end of each chapter. In most cases, the syntheses of compounds having high biological activity are considered.

Currently, the rapid progress in chemistry of organic peroxides is to a large degree determined by their high biological activity. In medicinal chemistry of peroxides, particular emphasis is given to the design of compounds having activity against causative agents of malaria and helminth infections. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers malaria as one of the most dangerous social diseases. Worldwide, 300–500 million cases of malaria occur each year, and 2 million people die from it [47–48].

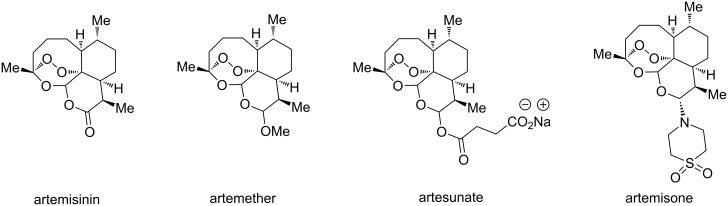

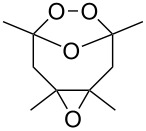

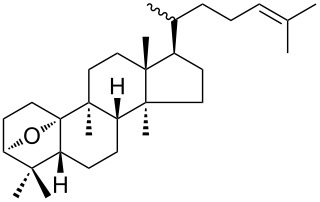

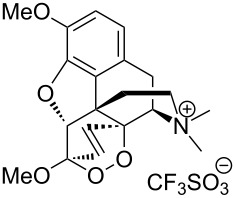

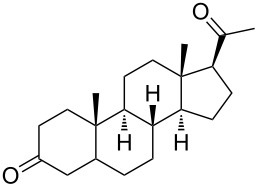

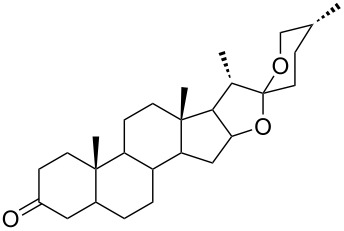

Due to a high degree of resistance in malaria to traditional drugs as quinine, chloroquine, and mefloquine, an active search for other classes of new drugs is performed. In this respect, organic peroxides play a considerable role. In medicinal chemistry of peroxides, artemisinin a natural peroxide exhibiting high antimalarial activity, is the most important drug in use for approximately 30 years. Artemisinin was isolated in 1971 from leaves of annual wormwood (Artemesia annua) [49–51]; the 1,2,4-trioxane ring V is the key pharmacophore of these drugs. A series of semi-synthetic derivatives of artemisinin were synthesized: artesunate, artemether, and artemisone (Figure 2). Currently, drugs based on these compounds are considered as the most efficacious for the treatment of malaria [52–76].

Figure 2.

Artemisinin and semi-synthetic derivatives.

The discovery of arterolane, a synthetic 1,2,4-trioxolane, is a considerable success in the search for easily available synthetic peroxides capable of replacing artemisinin and its derivatives in medical practice. Currently, this compound is currently in phase III clinical trials [77–81].

The mechanism of antimalarial action of peroxides is unusual for pharmaceutical chemistry. According to the commonly accepted mechanism, peroxides diffuse into Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes, and the heme iron ion of the latter reduces the peroxide bond to form a separated oxygen-centered radical anion, which rearranges to the C-centered radical having a toxic effect on Plasmodium [82–87].

In the course of the large-scale search for synthetically accessible and cheap antimalarial peroxides (compared with natural and semi-synthetic structures), it was found that structures containing 1,2-dioxolane [88–90], 1,2,4-trioxolane [91–101], 1,2-dioxane [102–112], 1,2-dioxene [113–119], 1,2,4-trioxane [120–127] or 1,2,4,5-tetraoxane rings [128–146] exhibit pronounced activity, and in some cases, even superior to that of artemisinin.

Another important field of medicinal chemistry of organic peroxides includes the search for antihelminthic drugs. For example, compounds containing 1,2-dioxolane [147], 1,2,4-trioxolane [148–152], 1,2,4-trioxane [153–158] or bridged 1,2,4,5-tetraoxane [159] moieties show activity against Schistosoma. Schistosomiasis is one of the most widespread helminthic diseases; 800 million people are at risk of acquiring this infection [160–174].

Additionally, based on synthetic peroxides, several compounds exhibiting antitumor activity were synthesized. These compounds contain 1,2-dioxolane [10–15,175–178], 1,2-dioxane [10–15,112,178–181], 1,2-dioxene [114,182–185] or 1,2,4-trioxane [10–15,175–176] rings. More than 300 peroxides are known to have a toxic effect on cancer cells [10–15,73,186–206].

Synthetic peroxides exhibit also other activities. For example, compounds containing the 1,2,4-trioxane ring are active against Trichomonas [207], compounds with the 1,2-dioxane ring show antitrypanosomal and antileishmanial activities [208–212], and compounds containing the 1,2-dioxene ring possess fungicidal [210,213–224] and antimycobacterial activities [128–131,225–228]. The present review covers literature relating to 5- and 6-membered cyclic peroxide chemistry published between 2000 and 2013.

Review

1. Synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes

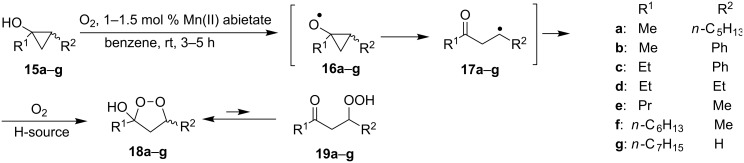

The modern approaches to the synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes are based on the use of oxygen and ozone for the formation of the peroxide moiety, the Isayama–Mukaiyama peroxysilylation, and reactions involving peroxycarbenium ions. Syntheses employing hydrogen peroxide and the intramolecular Kobayashi cyclization are less frequently used.

1.1. Use of oxygen for the peroxide ring formation

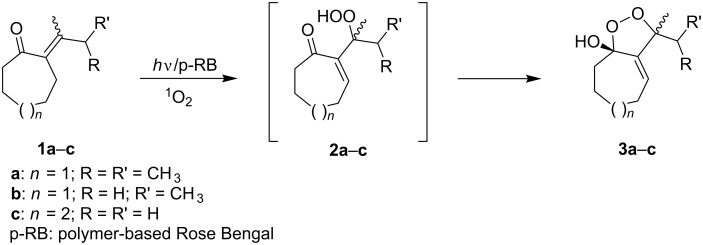

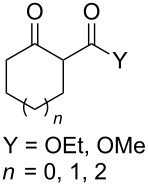

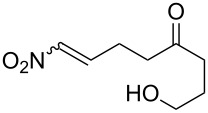

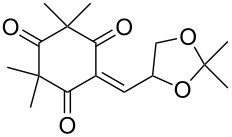

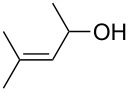

The singlet-oxygen ene reaction with alkenes provides an efficient tool for introducing the hydroperoxide function. The reaction starts with the coordination of oxygen to the double bond followed by the formation of hydroperoxides presumably by a stepwise or concerted mechanism [229–230]. The oxidation of α,β-unsaturated ketones 1a–c by singlet oxygen affords 3-hydroxy-1,2-dioxolanes 3a–c via the formation of β-hydroperoxy ketones 2a–c (Scheme 1) [231].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3-hydroxy-1,2-dioxolanes 3a–c.

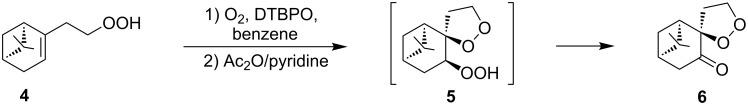

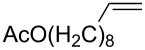

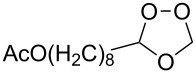

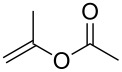

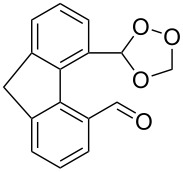

Dioxolane 6 was synthesized in 36% yield by the reaction of oxygen with hydroperoxide 4 in the presence of di-tert-butyl peroxalate (DTBPO) followed by the treatment of the reaction mixture with acetic anhydride and pyridine at room temperature (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dioxolane 6.

It should be emphasized that a mixture of dioxolanes 5 and 6 in a ratio of 7:3 is formed already in the first step [232].

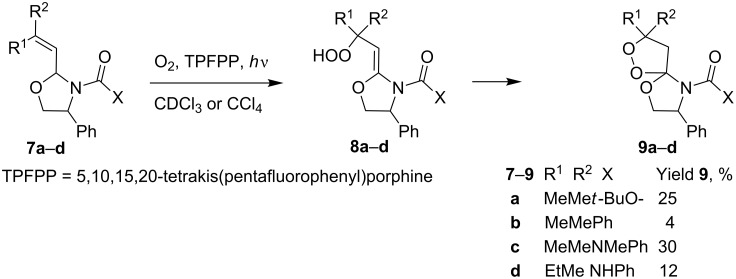

The photooxygenation of oxazolidines 7a–d through the formation of hydroperoxides 8a–d gives spiro-fused oxazolidine-containing dioxolanes 9a–d in low yields (12–30%) (Scheme 3) [233].

Scheme 3.

Photooxygenation of oxazolidines 7a–d with formation of spiro-fused oxazolidine-containing dioxolanes 9a–d.

The reaction was performed in a temperature range from −10 to −5 °С. The conversion of oxazolidines 7 and the yields of dioxolanes 9 were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

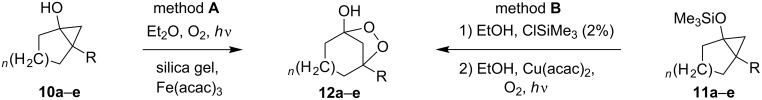

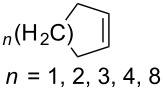

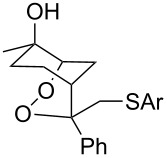

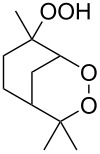

An efficient method for the synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes is based on the oxidation of cyclopropanes by oxygen in the presence of transition-metal salts as the catalysts. The reactions of bicycloalkanols 10a–e with singlet oxygen in the presence of catalytic amounts of Fe(III) acetylacetonate produce peroxides 12a–e, which can also be synthesized starting from silylated bicycloalkanols 11a–e with the use of Cu(II) acetylacetonate (Scheme 4, Table 1) [234].

Scheme 4.

Oxidation of cyclopropanes 10a–e and 11a–e with preparation of 1,2-dioxolanes 12a–e.

Table 1.

Structures and yields of dioxolanes 12a–e.

| Bicycloalkanol 10a–e, silylated bicycloalkanol 11a–e |

1,2-Dioxolane 12a–e | |||||

| Method Aa | Method Bb | |||||

| R | n | Reaction time, h | Yield, % | Reaction time, h | Yield, % | |

| a | CH3 | 1 | 3 | 35 | 5 | 54 |

| b | C4H9 | 1 | 3 | 55 | 3.5 | 84 |

| c | C6H13 | 1 | 3 | 68 | – | – |

| d | CH2Ph | 1 | 3 | 50 | 5 | 78 |

| e | CH3 | 2 | 36 | 54 | 6 | 80 |

aEt2O, O2, hν, silica gel, Fe(acac)3 (4 mol %).

bEtOH, O2, hν, Cu(acac)2 (4 mol %).

Similarly, the reactions of silylated bicycloalkanols 13a–c with oxygen in the presence of the catalyst VO(acac)2 yielded dioxolanes 14a–c, which made it possible to perform the oxidation without irradiation (Scheme 5, Table 2) [235].

Scheme 5.

VO(acac)2-catalyzed oxidation of silylated bicycloalkanols 13a–c.

Table 2.

Structures and yields of dioxolanes 14a–c.

| Silylated bicycloalkanol 13a–c |

||||

| R1 | R2 | Solvent | Yield 14a–c, % |

|

| a | H | Me | EtOH | 45 |

| CF3CH2OH | 86 | |||

| b | H | Bn | CF3CH2OH | 43 |

| c | Me | Me | CF3CH2OH | 43 |

This reaction gives β-hydroxyketones as by-products that are formed as a result of the decomposition of dioxolanes 14.

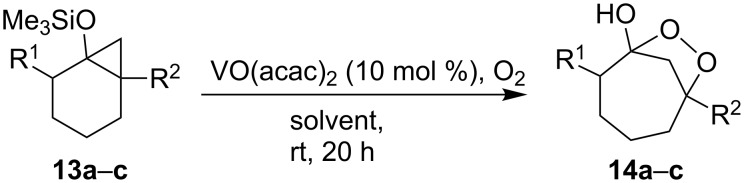

Cyclopropanols 15a–g are readily oxidized by molecular oxygen in the presence of Mn(II) abietate or acetylacetonate (Scheme 6) [236].

Scheme 6.

Mn(II)-catalyzed oxidation of cyclopropanols 15a–g.

Presumably, the reaction proceeds via the intermediate formation of О- and С-centered radicals 16a–g and 17a–g, respectively. According to this method, dioxolanes 18a–g (exist in equilibrium with the open form 19a–g) were synthesized in 60–80% yields.

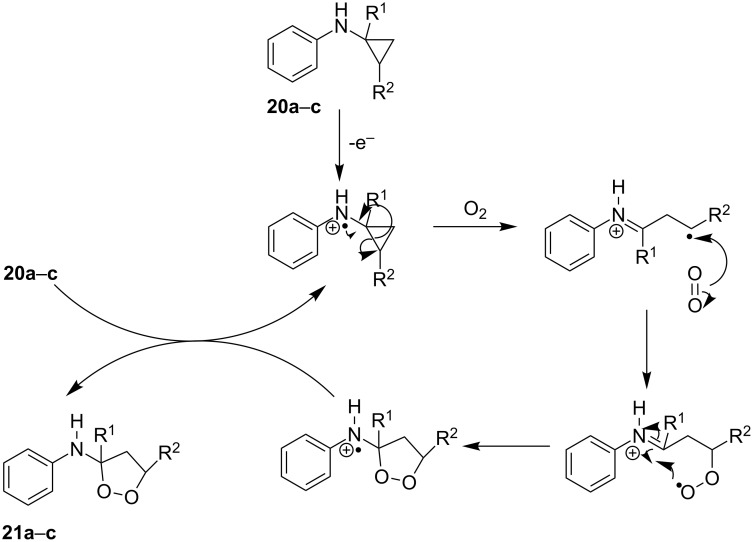

Like hydroxycyclopropanes, aminocyclopropanes are transformed into 1,2-dioxolanes. For example, N-cyclopropyl-N-phenylamines 20a–c form dioxolanes 21a–c in the presence of atmospheric oxygen (Table 3). It was found that the reaction rate substantially increases in the presence of catalytic amounts of [(phen)3Fe(III)(PF6)3] or equimolar amounts of benzoyl peroxide or di-tert-butyl peroxide. The possible mechanism of the oxidation is shown in Scheme 7 [237].

Table 3.

Peroxidation of N-cyclopropyl-N-phenylamines 20a–c to form 3-(1,2-dioxalanyl)-N-phenylamines 21a–c.

| Dioxolane 21a–c | |||

| R1 | R2 | Reaction conditions | |

| a | H | H | 1. (BzO)2 (1 mol/1 mol 20a), CHCl3, dark, −20 °C, 3 days. 2. (t-BuO)2 (1 mol/1 mol 20a), CHCl3, UV (254 nm), ambient temperature, aerobic, 2 h. 3. [(phen)3Fe(III)(PF6)3] (0.6 % mol), CHCl3, ambient temperature, aerobic, 1 h. |

| b | Me | H | 1. (t-BuO)2 (1 mol/1 mol 20b), CHCl3, UV (254 nm), ambient temperature, aerobic, 2 h. |

| c | H | Me | 1. (t-BuO)2 (1 mol/1 mol 20c), CHCl3, UV (254 nm), ambient temperature, aerobic, 2 h. 2. [(phen)3Fe(III)(PF6)3] (0.6 % mol), CHCl3, ambient temperature, aerobic, 1 h. |

Scheme 7.

Oxidation of aminocyclopropanes 20a–c.

According to the 1H NMR data, dioxolanes 21a–c are formed under the above-mentioned conditions in almost quantitative yields; the yields based on the isolated product were not higher than 80% [237].

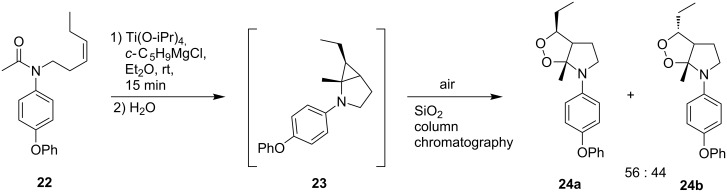

Structurally similar 3-ethyl-6a-methyl-6-(4-phenoxyphenyl)hexahydro[1,2]dioxolo[3,4-b]pyrroles 24a and 24b were synthesized from (Z)-N-(hex-3-enyl)-N-(4-phenoxyphenyl)acetamide (22). It was suggested that aminocyclopropane 23 is formed in situ, which is subsequently oxidized in air on silica gel (Scheme 8) [238]. The total yield of both isomers 24 was 31%.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of aminodioxolanes 24.

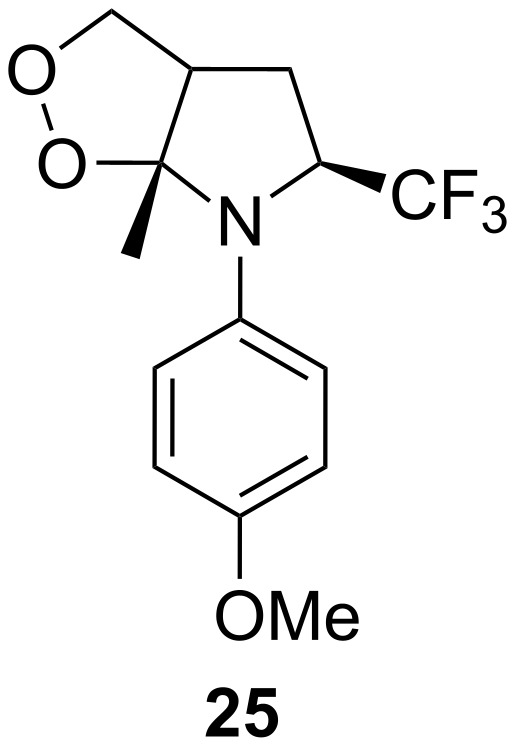

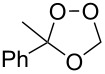

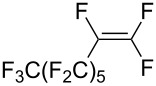

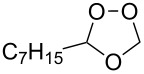

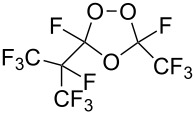

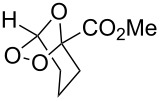

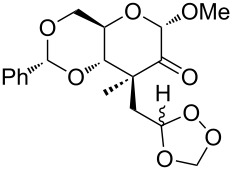

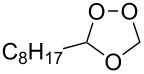

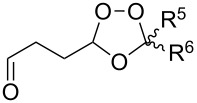

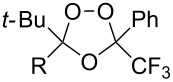

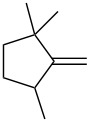

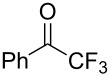

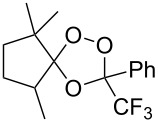

Trifluoromethyl-containing dioxolane 25 (Figure 3) was synthesized according to this method in 40% yield [239].

Figure 3.

Trifluoromethyl-containing dioxolane 25.

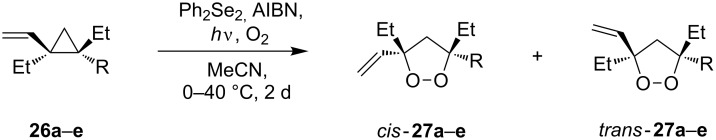

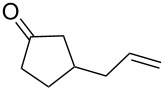

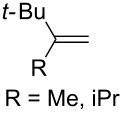

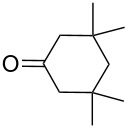

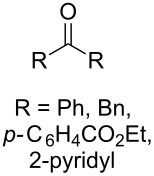

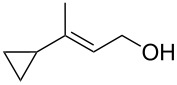

A series of 1,2-dioxolanes 27a–e containing various functional groups R were prepared by the oxidation of cyclopropanes 26a–e (Scheme 9, Table 4).

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes 27a–e by the oxidation of cyclopropanes 26a–e.

Table 4.

Structures and yields of dioxolanes 27a–e.

| Dioxolane 27a–e |

R | Yield (cis + trans), % |

Ratio (cis/trans) |

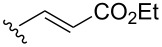

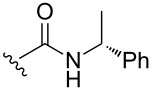

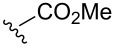

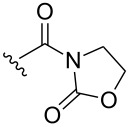

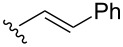

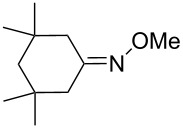

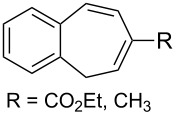

| a |  |

88 | 1/7 |

| b |  |

100 | trans isomer |

| c |  |

75 | 1/22 |

| d |  |

100 | 1/13 |

| e |  |

82 | 1/2.8 |

The reaction was performed in the presence of Ph2Se2 (10 mol %) and azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, 8 mol %) in air under irradiation for two days. The product was purified by flash chromatography to obtain a mixture of cis and trans isomers, whose ratio depends primarily on the nature of the substituent in cyclopropanes 26a–e [240].

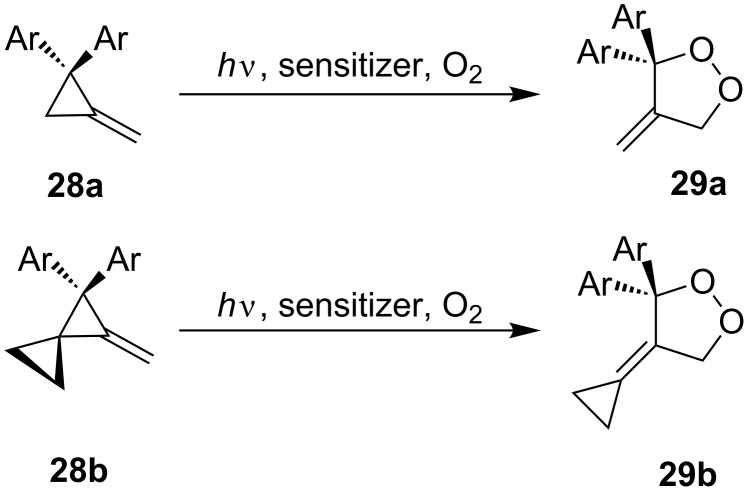

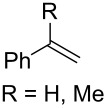

The oxidation of methylenecyclopropanes 28a and 28b under photoinduced electron-transfer conditions is described by a similar scheme (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10.

Photoinduced oxidation of methylenecyclopropanes 28.

The reaction was performed in acetonitrile or in a mixture of toluene and acetonitrile with the use of 9,10-dicyanoanthracene (DCA), 1,2,4,5-tetracyanobenzene (TCNB), or N-methyl-quinolinium tetrafluoroborate (NMQ+BF4−) as sensitizers. Under these conditions, dioxolane 29a was obtained in quantitative yield (1H NMR data), the yield of 29b was not reported [241].

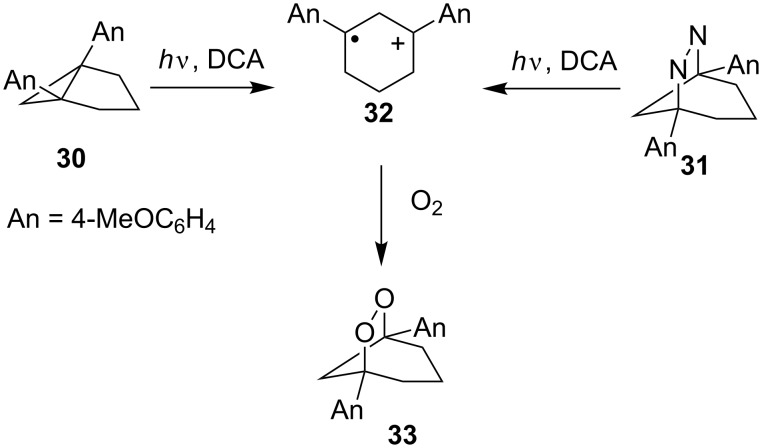

Under irradiation in the presence of oxygen, 1,5-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane (30) and 1,5-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)-6,7-diazabicyclo[3.2.1]oct-6-ene (31) were transformed into bicyclic dioxolane 33. It was suggested that both reactions proceed via the formation of 1,3-radical cation 32 (Scheme 11).

Scheme 11.

Irradiation-mediated oxidation.

Dioxolane 33 was synthesized in the highest yields (91% from 30 and 100% from 31) in acetonitrile with the use of 9,10-dicyanoanthracene (DCA) as the sensitizer [242].

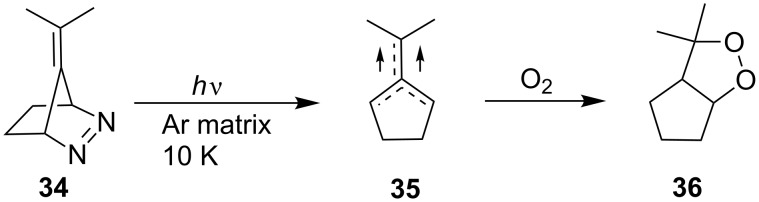

After irradiation of diazene 34 in an argon matrix at 10 K, biradical 35 was detected by IR spectroscopy and the reaction of the latter with oxygen at 10 K proceeded regioselectively to give dioxolane 36 (Scheme 12) [243].

Scheme 12.

Application of diazene 34 for dioxolane synthesis.

Bicyclic peroxide 2-heptyl-3,4-dioxabicyclo[3.3.0]oct-1(8)-ene was prepared by a similar process [244].

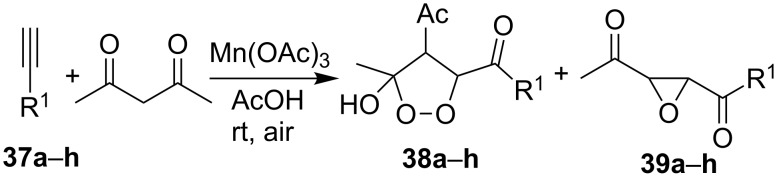

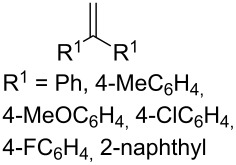

The oxidation of arylacetylenes 37a–h with atmospheric oxygen in the presence of catalytic amounts of Mn(OAc)3 in an excess of acetylacetone afforded dioxolanes 38a–h in moderate yields (34–64%) (Scheme 13, Table 5) [245].

Scheme 13.

Mn(OAc)3-catalyzed cooxidation of arylacetylenes 37a–h and acetylacetone with atmospheric oxygen.

Table 5.

Structures and yields of dioxolanes 38a–h and epoxides 39a–h.

| 37a–h | R1 | Yield 38a–h, % | Yield 39a–h, % |

| a | Ph | 45 | 5 |

| b | 4-MeC6H4 | 52 | 7 |

| c | 4-MeOC6H4 | 64 | 2 |

| d | 4-ClC6H4 | 38 | 2 |

| e | 4-FC6H4 | 41 | 6 |

| F | 1-naphthyl | 54 | 6 |

| g | 2-naphthyl | 52 | 8 |

| h | 3,4-(MeO)2C6H3 | 34 | 11 |

The reaction was performed at 23 °С in glacial acetic acid in air; the 37/acetylacetone/Mn(OAc)3 molar ratio was 1/10/10. The reaction gave oxiranes 39 as by-products, which can also be synthesized in quantitative yields by the treatment of dioxolanes 38 with silica gel in methanol [245].

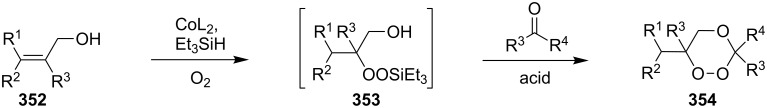

1.2. Peroxidation of alkenes with the Co(II)/Et3SiH/O2 system (Isayama–Mukaiyama reaction)

Peroxysilylation of alkenes with molecular oxygen in the presence of triethylsilane catalyzed by cobalt(II) diketonates was described for the first time by S. Isayama and T. Mukaiyama in 1989 [246–247]. Currently, this approach is one of the main methods for the preparation of peroxides from alkenes.

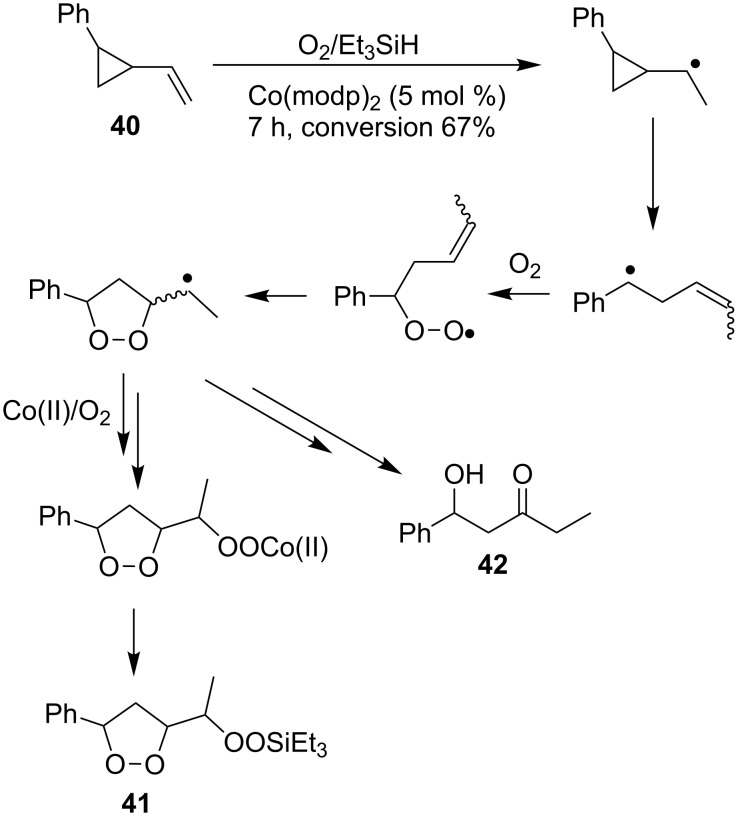

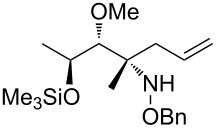

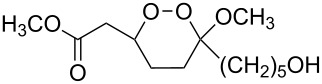

Compounds (oxidized by the Isayama–Mukaiyama reaction) containing a reaction center that can be subjected to the attack by a peroxide radical, are able to undergo intramolecular cyclization to form the 1,2-dioxolane ring. For example, the Co(modp)2-catalyzed peroxysilylation (modp = 1-morpholino-5,5-dimethyl-1,2,4-hexanetrionate) of (2-vinylcyclopropyl)benzene (40) affords triethyl(1-(5-phenyl-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)ethylperoxy)silane (41) in 37% yield (Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

Peroxidation of (2-vinylcyclopropyl)benzene (40).

The reaction was carried out in 1,2-dichloroethane at room temperature, and the reaction products were separated by column chromatography. 1-Hydroxy-1-phenylpentan-3-one (42) was isolated as a by-product in 16% yield [248].

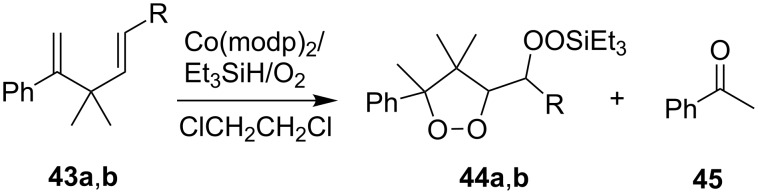

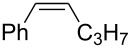

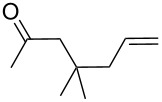

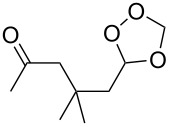

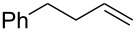

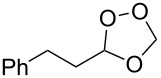

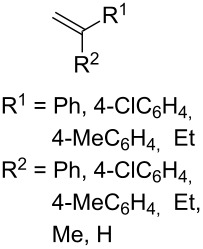

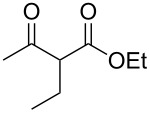

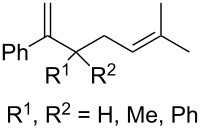

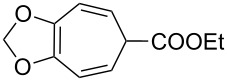

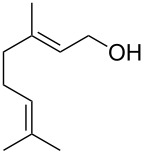

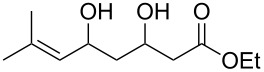

The peroxidation of 1,4-dienes 43a,b with the Co(modp)2/Et3SiH/O2 system according to a similar reaction scheme gave dioxolanes 44a,b. Acetophenone (45) was obtained as the by-product (Scheme 15, Table 6) [249].

Scheme 15.

Peroxidation of 1,4-dienes 43a,b.

Table 6.

Synthesis of dioxolanes 44a,b.

| 1,4-Diene 43 |

R | Reaction time, h |

Conversion, % |

Yield, % | |

| 44 | 45 | ||||

| a | H | 4.5 | 47 | 27 | 49 |

| b | COOEt | 2 | 44 | 56 | 22 |

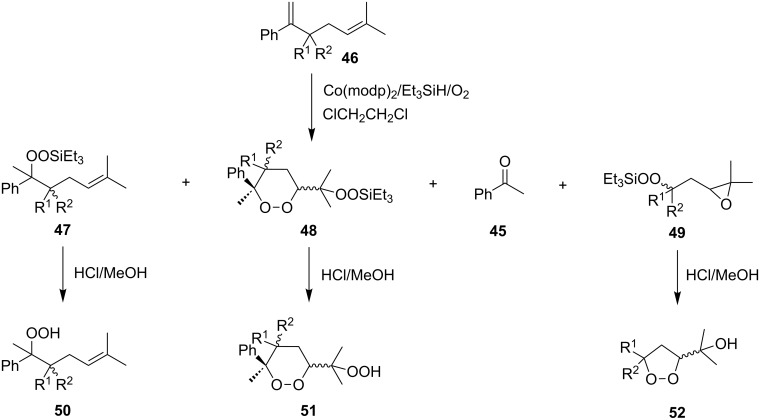

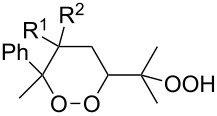

The desilylation of the initially formed silicon peroxide followed by cyclization of the hydroperoxide accompanied by the attack on the electrophilic center is another example of the use of the Isayama–Mukaiyama reaction for the synthesis of cyclic peroxides. In some cases, the reaction with 1,5-dienes 46a–d produces, along with 1,2-dioxanes 51 (desilylation products of the corresponding 1,2-dioxanes 48), 1,2-dioxolanes (52b,d) as a result of cyclization of the corresponding peroxysilyl epoxides 49. In these reactions, unsaturated triethylsilyl peroxides 47 are formed as by-products, which are desilylated during hydrolysis to give the unsaturated hydroperoxides 50 (Scheme 16, Table 7) [249].

Scheme 16.

Peroxidation of 1,5-dienes 46.

Table 7.

Peroxidation of 1,5-dienes 46.

| Diene 46 | R1 | R2 | Reaction time, h | Conversion, % | Yielda, % | ||||

| 45 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | |||||

| a | H | H | 6 | 82 | 4 | – | 13 | 31 | – |

| b | H | Me | 2.5 | 83 | 36 | – | 12 | 13 | 33 |

| c | H | Ph | 3.5 | 75 | 57 | 38 | 7 | 27 | – |

| d | Me | Me | 3 | 84 | 51 | – | – | 31 | 26 |

aThe yields are given based on the converted dienes 46a–d.

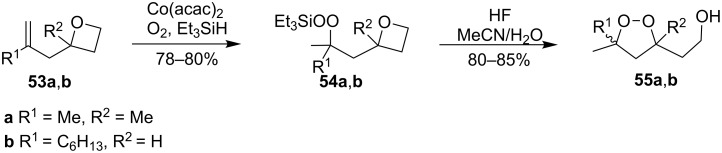

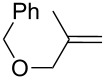

1,2-Dioxolanes can be produced from oxetanes 53a,b containing a double bond in the side chain according to a similar scheme. The first step afforded peroxysilanes 54a,b, which upon treatment with aqueous HF gave the target dioxolanes 55a,b (Scheme 17) [250].

Scheme 17.

Peroxidation of oxetanes 53a,b.

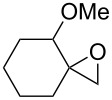

A similar way to 1,2-dioxolanes used an oxirane cycle for the stages of ring opening followed by 1,2-dioxolane ring closing [251].

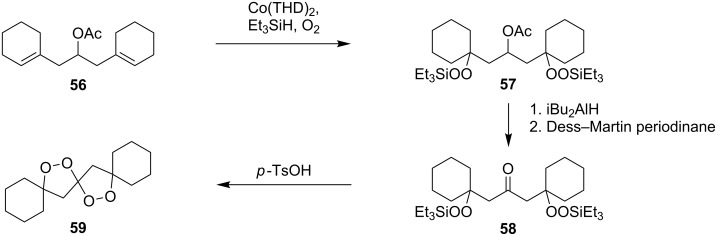

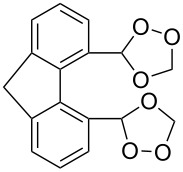

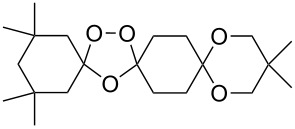

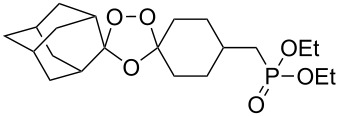

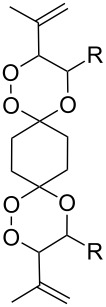

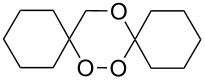

The synthesis of spirodioxolane 59 involved the peroxysilylation of 1,3-dicyclohexenylpropan-2-yl acetate (56) catalyzed by cobalt complexed with 2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dione (Co(THD)2) as the first step giving 1,3-bis(1-(triethylsilylperoxy)cyclohexyl)propan-2-yl acetate (57) that was subsequently transformed into the carbonyl-containing diperoxide (1,3-bis(1-(triethylsilylperoxy)cyclohexyl)propan-2-one) (58) in two steps. The latter was treated with p-TsOH to give the target peroxide 59 (Scheme 18) [252].

Scheme 18.

Peroxidation of 1,6-diene 56.

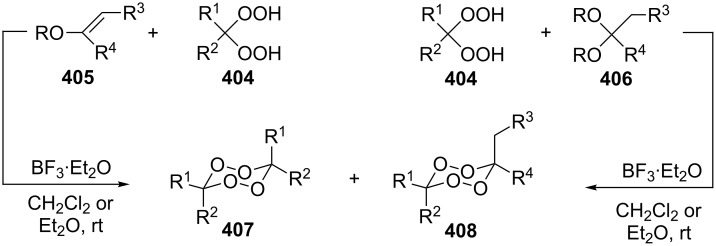

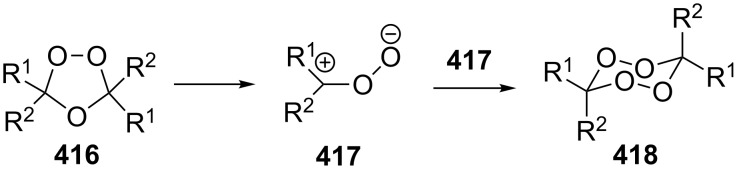

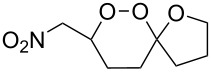

1.3. The use of ozone. Peroxycarbenium ions in the 1,2-dioxolanes synthesis

The ozonolysis of unsaturated compounds is a reliable and facile method for the introduction of the peroxide functional group. As in the above-considered studies, the intramolecular cyclization of ozonolysis products can be performed with the use of the hydroperoxide group provided that there is an appropriate electrophilic center.

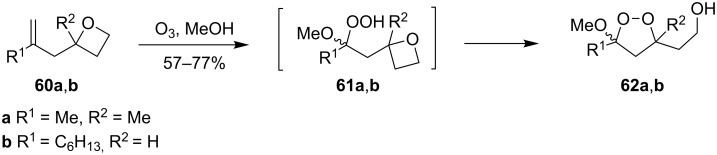

The reaction of oxetanes 60a,b with ozone in methanol produced 3-alkoxy-1,2-dioxolanes 62a,b. The analysis of the reaction mixture (TLC, NMR) confirmed that cyclic peroxides are formed immediately in the reaction mixture rather than in the course of the treatment or purification of the reaction products. It was suggested that the reaction proceeds via the formation of hydroperoxy acetals 61a,b (Scheme 19) [250].

Scheme 19.

Synthesis of 3-alkoxy-1,2-dioxolanes 62a,b.

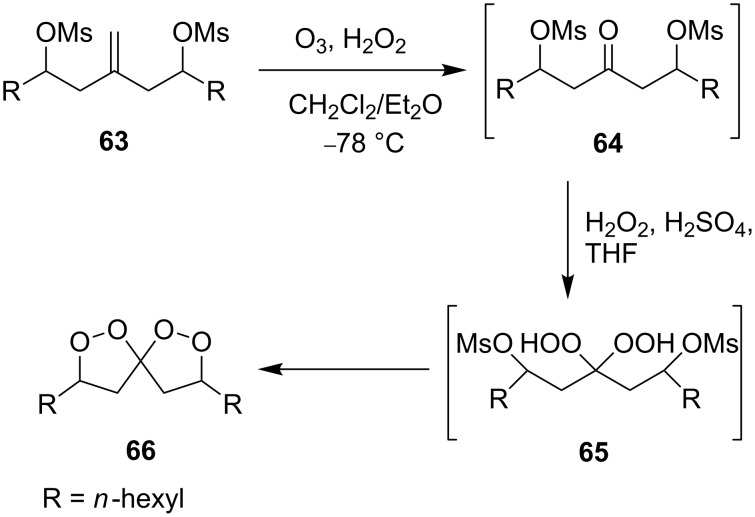

The ozonolysis of 9-methyleneheptadecane-7,11-diyl-bis(methanesulfonate) (63) gave 9-oxoheptadecane-7,11-diyl-bis(methanesulfonate) (64). The latter reacted with H2O2 in the presence of sulfuric acid (or iodine) as the catalyst to form 9,9-dihydroperoxyheptadecane-7,11-diyl-bis(methanesulfonate) 65, and the replacement of the mesyl groups in the latter compound afforded 3,8-dihexyl-1,2,6,7-tetraoxaspiro[4.4]nonane (66, Scheme 20). The yield of dioxolane 66 was 36% based on 63 [252].

Scheme 20.

Synthesis of spiro-bis(1,2-dioxolane) 66.

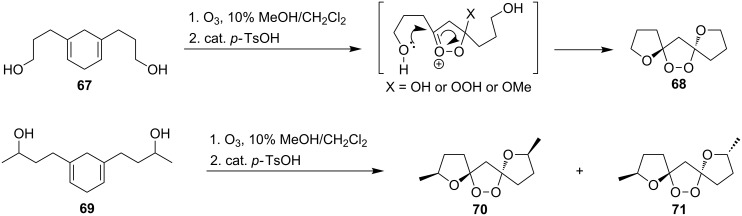

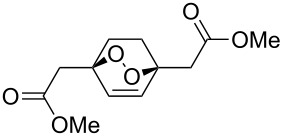

The treatment of 3,3'-(cyclohexa-3,6-diene-1,3-diyl)dipropan-1-ol (67) and 4,4'-(cyclohexa-3,6-diene-1,3-diyl)dibutan-2-ol (69) with ozone in MeOH/CH2Cl2 followed by the addition of a catalytic amount of p-TsOH lead to the intramolecular peroxyketalization that proceeds through the formation of the peroxycarbenium ion (shown in Scheme 21 for the ozonolysis of 67 as an example) to give finally dispiro-1,2-dioxolanes: 1,8,12,13-tetra-oxadispiro-[4.1.4.2]tridecane 68 (yield 67%) and two isomers of 2,9-dimethyl-1,8,12,13-tetraoxadispiro[4.1.4.2]tridecane 70 and 71 (combined yield 72%) (Scheme 21) [253].

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of dispiro-1,2-dioxolanes 68, 70, 71.

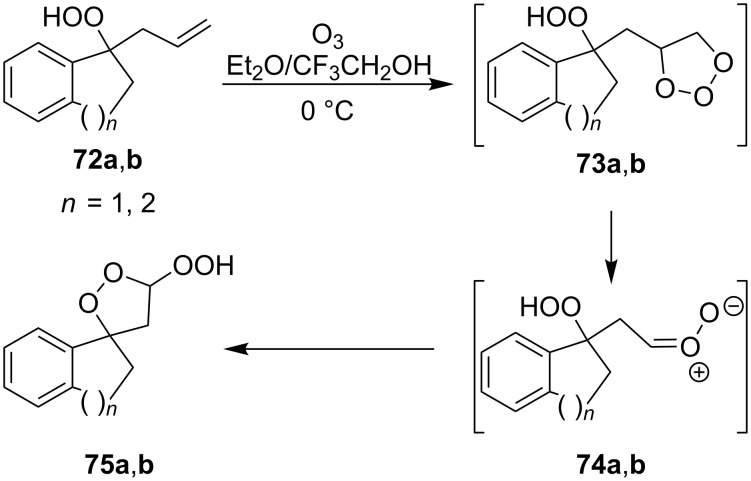

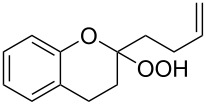

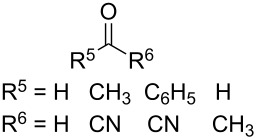

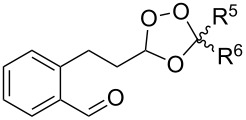

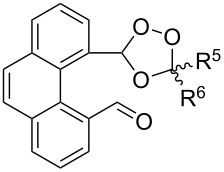

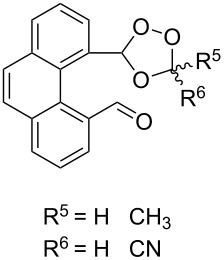

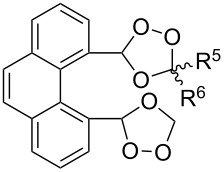

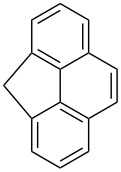

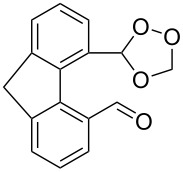

The spirohydroperoxydioxolanes, 5-hydroperoxy-2',3'-dihydrospiro[[1,2]dioxolane-3,1'-indene] (75a) and 5-hydroperoxy-3',4'-dihydro-2'H-spiro[[1,2]dioxolane-3,1'-naphthalene] (75b), were synthesized by the ozonolysis of 1-allyl-1-hydroperoxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene (72a) and 1-allyl-1-hydroperoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene (72b), respectively, in an Et2O/CF3CH2OH system (2:1). The reaction proceeds via the formation of ozonide 73 followed by elimination of formaldehyde to give peroxycarbenium ion 74 that undergoes cyclization via the attack of the hydroperoxide group on the carbon center of peroxycarbenium ion 74 (Scheme 22) [254].

Scheme 22.

Synthesis of spirohydroperoxydioxolanes 75a,b.

Spirohydroperoxydioxolane 75a (n = 1) was obtained in 71% yield (the diastereoisomeric ratio was 1:1); the yield of 75b (n = 2) was 21% (the diastereoisomeric ratio was 1:1).

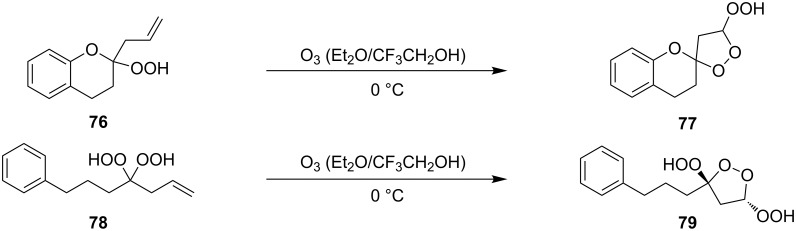

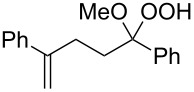

5'-Hydroperoxyspiro[chromane-2,3'-[1,2]dioxolane] (77, yield 18%) and (3S,5S)-3,5-dihydroperoxy-3-(3-phenylpropyl)-1,2-dioxolane (79, yield 22%) (Scheme 23) were synthesized in a similar way starting from 2-allyl-2-hydroperoxychromane (76) and (4,4-dihydroperoxyhept-6-enyl)benzene (78), respectively [254].

Scheme 23.

Synthesis of spirohydroperoxydioxolane 77 and dihydroperoxydioxolane 79.

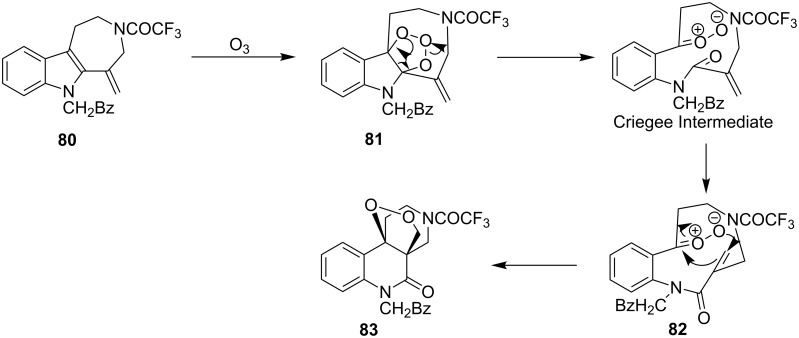

An oxidative rearrangement takes place in the reaction of azepino[4,5-b]indole 80 with ozone. The addition of ozone to the endocyclic double bond (molozonide 81) and the formation of the Criegee intermediate are followed by a 1,3-dipolar interaction of the peroxycarbenium ion with the double bond (82) to form dioxolane 83. The yield was not lower than 48% but no exact yield was reported (Scheme 24) [255].

Scheme 24.

Ozonolysis of azepino[4,5-b]indole 80.

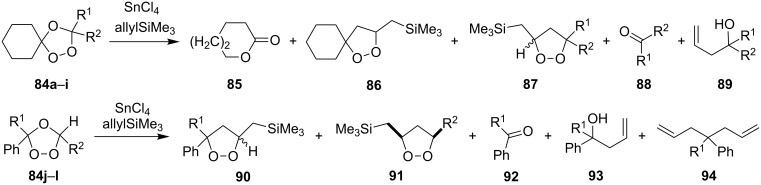

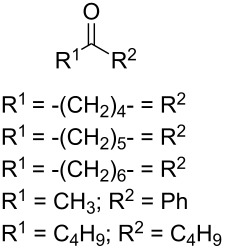

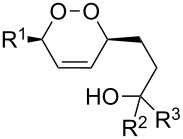

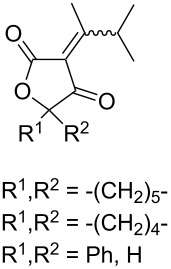

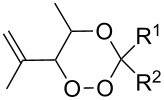

The peroxycarbenium ions produced by the decomposition of 1,2,4-trioxolanes can be trapped with allyltrimethylsilane. For example, the SnCl4-mediated fragmentation of ozonides 84a–l in the presence of allyltrimethylsilane in dichloromethane gives a complex mixture of products 85–94, including dioxolanes 86a–i, 87i, 90j–l, and 91j (Scheme 25, Table 8) [256].

Scheme 25.

SnCl4-mediated fragmentation of ozonides 84a–l in the presence of allyltrimethylsilane.

Table 8.

The SnCl4-mediated fragmentation of ozonides 84a–l in the presence of allyltrimethylsilane.

| Yield, % | ||||||||

| Ozonide 84 | R1 | R2 | T, °С | Lactone 85 | Dioxolane 86 | Dioxolane 87 | Ketone 88 | Alcohol 89 |

| a | -(CH2)4- | −78 to 0 | 11 | 50 | – | 88a (traces) | – | |

| b | -(CH2)5- | −78 to 0 | 17 | 57 | – | 88b (traces) | – | |

| c | -(CH2)6- | −78 to 0 | 39 | 24 | – | 88c (traces) | – | |

| d | CH3 | Ph | −78 to 0 | 25 | 61 | – | 88d (93%) | – |

| e | C4H9 | C4H9 | −78 to 0 | 40 | 14 | – | 88e (70%) | 75 |

| f | H | C8H17 | −78 | – | 56 | – | – | 50 |

| g | H | Ph | −78 | – | 79 | – | – | 13 |

| h | H | H | −78 | – | 10 | – | – | – |

| i | CH3 | C(CH3)3 | −78 to 0 | 31 | 21 | 9 (cis) | – | – |

| Ozonide 84 | R1 | R2 | T, °С | Dioxolane 90 (cis:trans) | Dioxolane 91 | Carbonyl compound 92 | Alcohol 93 | Alkene 94 |

| j | H | C3H7 | −78 | 15 (1:1) | 7 | 39 | 93j (20%) | – |

| k | H | H | −78 | 15 (1:1) | – | 22 | 93j (24%) | – |

| l | CH3 | H | −78 | 9 (1:1) | – | 43 | – | 2.5 |

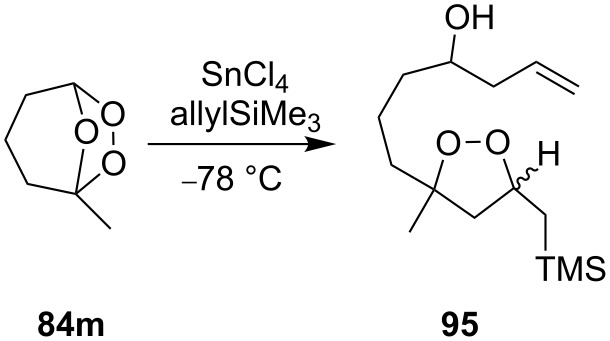

Treatment of the bicyclic ozonide 1-methyl-6,7,8-trioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octane 84m, with SnCl4 in the presence of allyltrimethylsilane produces a mixture of two cis diastereomers and two trans diastereomers (in a ratio of 35:35:15:15) of 7-(3-methyl-5-((trimethylsilyl)methyl)-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)hept-1-en-4-ol 95 in a total yield of 48% (Scheme 26) [256].

Scheme 26.

SnCl4-mediated fragmentation of bicyclic ozonide 84m in the presence of allyltrimethylsilane.

These syntheses of dioxolanes involve the formation of the peroxycarbenium ion as the key step. The reaction of the latter with allyltrimethylsilane followed by the intramolecular cyclization finally leads to the dioxolane ring.

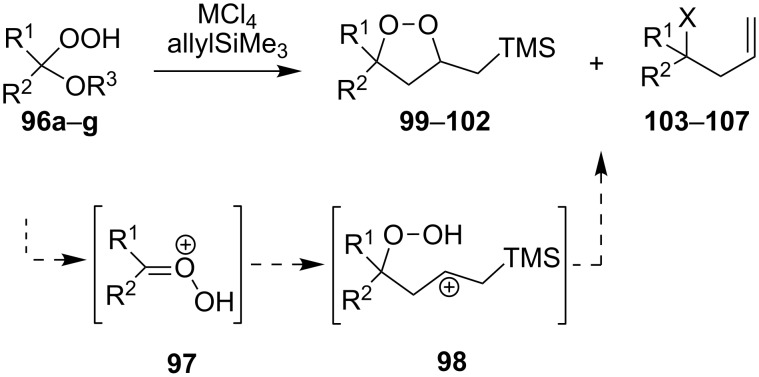

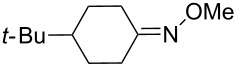

Dioxolanes 99–102 are produced from alkoxyhydroperoxides 96a–g (ozonolysis products of alkenes) in a similar way. The first step results in the formation of peroxycarbenium ions 97, which are trapped with allyltrimethylsilane under the formation of intermediate hydroperoxides 98. Then either cyclic dioxolanes 99–102 or unsaturated compounds 103–107 are formed as the major reaction products depending on the nature of the substituents and the Lewis acid (Scheme 27, Table 9) [257].

Scheme 27.

MCl4-mediated fragmentation of alkoxyhydroperoxides 96 in the presence of allyltrimethylsilane.

Table 9.

Synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes 99–102.

| Hydroperoxide 96 | R1 | R2 | R3 | M | Dioxolane 99–102 (yield, %) | Alkene 103–107 (X, yield, %) |

| a | Me | Me | Me | Ti | 99 (31) | – |

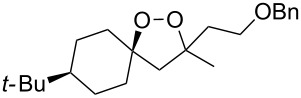

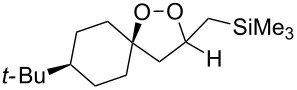

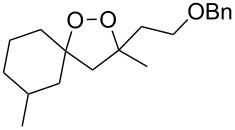

| b | Me | Me | (CH2)2OMe | Sn | 99 (56) | – |

| b | Me | Me | (CH2)2OMe | Ti | 99 (12) | 103 (–OOH, 23) |

| с | 4-tert-butyl- cyclohexylidene |

Me | Ti | – | 104 (–O2–, 31) | |

| c | 4-tert-butyl- cyclohexylidene |

Me | Sn | 100 (42) | – | |

| d | 4-tert-butyl- cyclohexylidene |

(CH2)2OMe | Sn | 100 (59) | – | |

| e | Me | BnOCH2 | Me | Ti | 101 (12) | 105 (=O, 62) |

| f | Bu | H | Me | Ti | 102 (7) | 106 (OMe, 63) |

| g | Bu | H | (CH2)2OMe | Ti | 102 (15) |

107 (O(CH2)2OMe, the yield was not determined) |

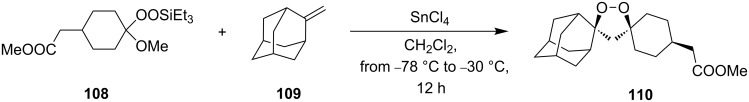

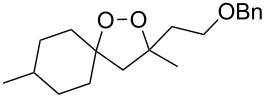

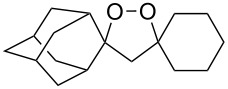

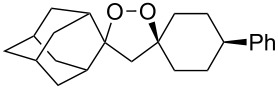

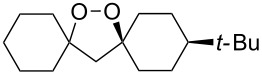

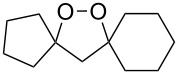

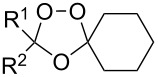

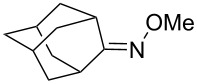

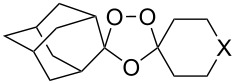

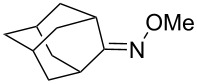

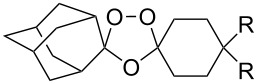

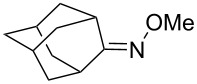

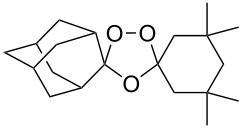

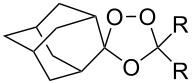

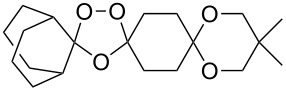

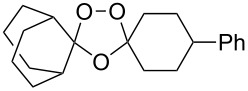

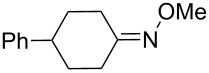

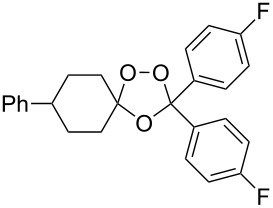

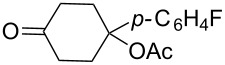

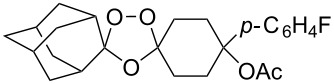

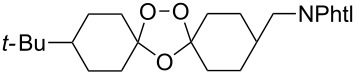

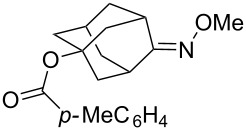

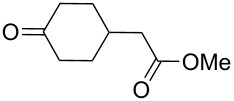

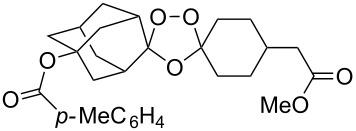

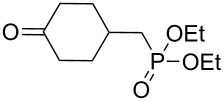

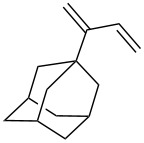

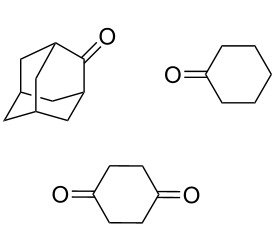

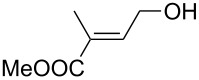

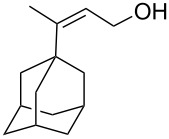

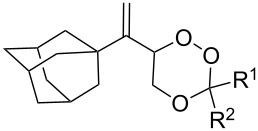

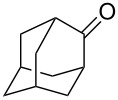

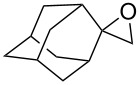

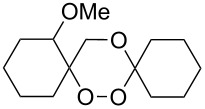

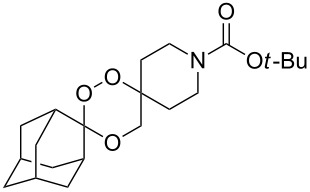

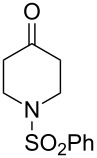

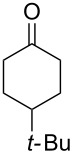

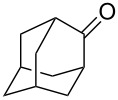

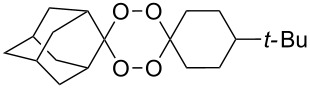

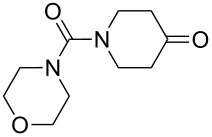

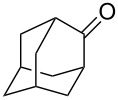

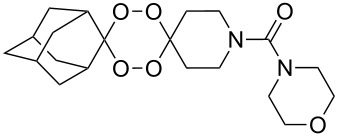

The reaction of trialkylsilylperoxyacetals with alkenes in the presence of Lewis acids also proceeds through the formation of peroxycarbenium ions. For example, the reaction of methyl 2-(4-methoxy-4-(triethylsilylperoxy)cyclohexyl)acetate (108) with 2-methyleneadamantane (109) produced adamantane-2-spiro-3’,8’-methoxycarbonylmethyl-1’,2’-dioxaspiro[4.5]decane (110) in 40% yield (Scheme 28) [258].

Scheme 28.

SnCl4-catalyzed reaction of monotriethylsilylperoxyacetal 108 with alkene 109.

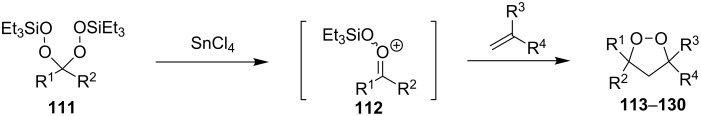

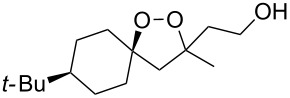

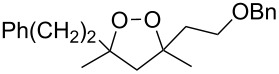

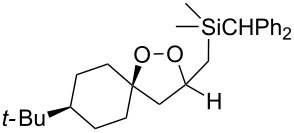

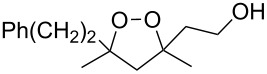

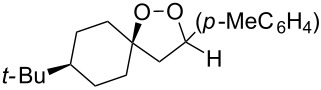

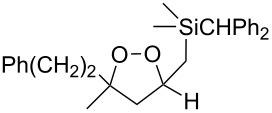

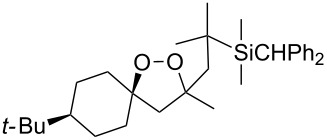

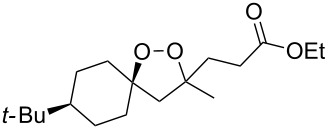

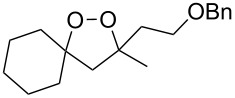

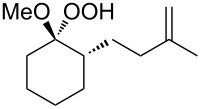

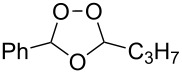

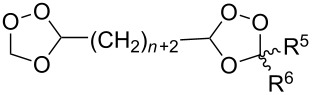

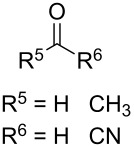

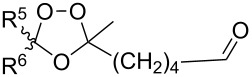

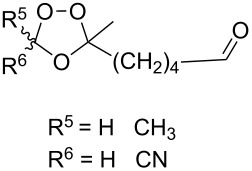

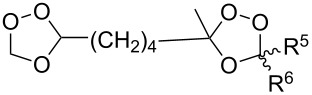

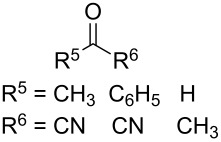

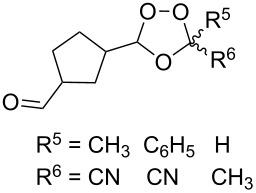

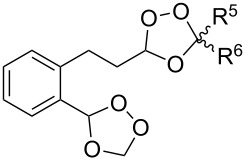

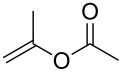

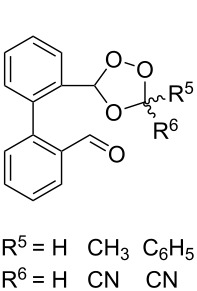

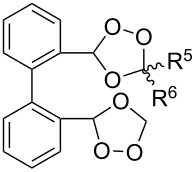

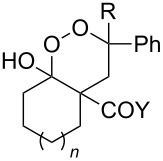

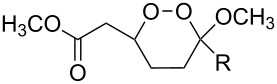

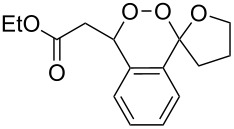

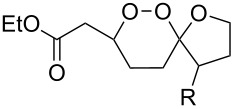

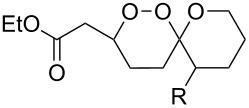

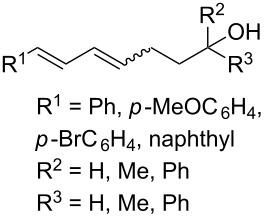

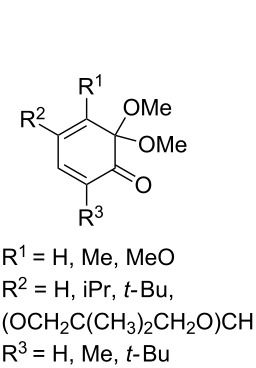

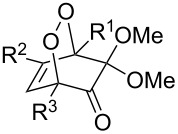

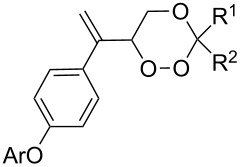

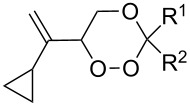

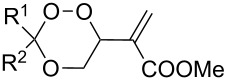

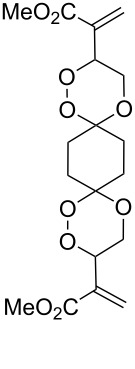

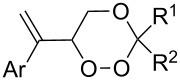

The use of easily accessible triethylsilylperoxyacetals 111 as the starting materials for the generation of silylperoxycarbenium ions 112 enabled the synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes containing various functional groups 113–130 in good yields by the reactions with alkenes (Scheme 29, Table 10) [88,90,259].

Scheme 29.

SnCl4-catalyzed reaction of triethylsilylperoxyacetals 111 with alkenes.

Table 10.

Structures and yields of 1,2-dioxolanes 113–130.

| Product | Structure | Yielda, % | Product | Structure | Yielda, % |

| 113 |  |

80 | 122 |  |

92 |

| 114 |  |

72 | 123 |  |

47 |

| 115 |  |

57 | 124 |  |

72 |

| 116 |  |

67 | 125 |  |

28 |

| 117 |  |

57 | 126 |  |

48 |

| 118 |  |

34 | 127 |  |

59 |

| 119 |  |

46 | 128 |  |

51 |

| 120 |  |

74 | 129 |  |

68 |

| 121 |  |

94 | 130 |  |

90 |

aReagents and conditions: SnCl4 (1.0–2.0 equiv), alkene (1.0–3.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, from −78 °С to 25 °С, 2–24 h.

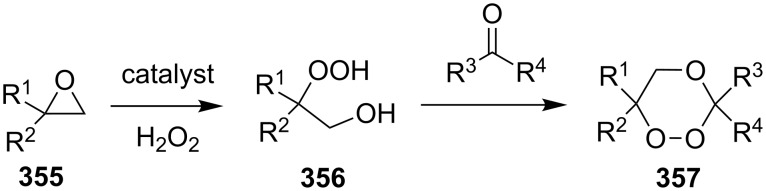

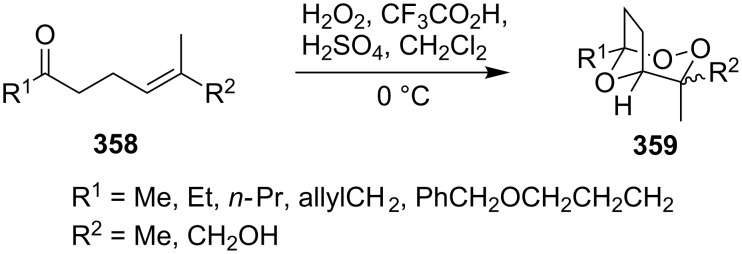

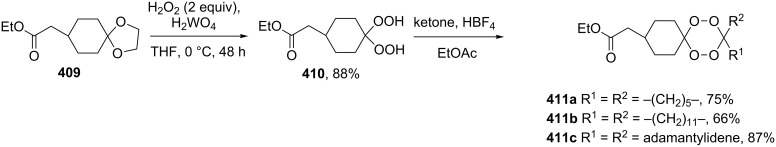

1.4. Methods for the synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes from hydrogen peroxide and hydroperoxides

This section deals with reactions, in which hydrogen peroxide or hydroperoxides are used for the construction of the five-membered peroxide ring. In all syntheses, the final (key) step involves the intramolecular cyclization of hydroperoxide with the attack on the electrophilic center (an activated double bond or a carbon atom of a keto or ester group).

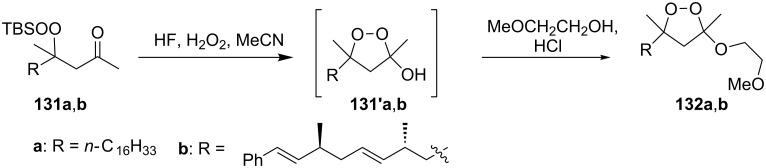

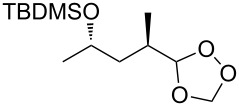

The desilylation of tert-butyldimethylsilylperoxy ketones 131a,b with HF followed by cyclization and subsequent reaction with monomethylethylene glycol afforded dioxolanes 132a,b in 75 and 88% yield, respectively. The intermediate hydroxydioxolanes 131'a,b were used in the second step without isolation (Scheme 30) [260]. A series of analogues of plakinic acids were synthesized by the modification of the peroxyketal moiety of dioxolanes 132a and 132b [260].

Scheme 30.

Desilylation of tert-butyldimethylsilylperoxy ketones 131a,b followed by cyclization.

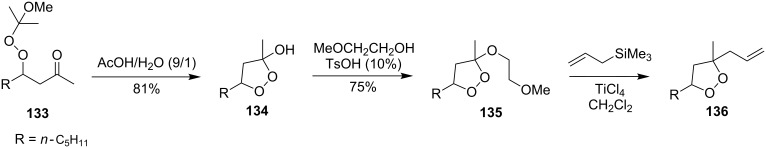

The monoperoxy ketal moiety of 4-(2-methoxypropan-2-ylperoxy)nonan-2-one (133) was used for the generation of the hydroperoxide group. The intramolecular cyclization afforded 3-methyl-5-pentyl-1,2-dioxolan-3-ol (134), which could be easily reacted with monomethylethylene glycol to form 3-(2-methoxyethoxy)-3-methyl-5-pentyl-1,2-dioxolane (135). Allylation of the latter produced 3-allyl-3-methyl-5-pentyl-1,2-dioxolane (136) in 47% yield (Scheme 31) [261].

Scheme 31.

Deprotection of peroxide 133 followed by cyclization.

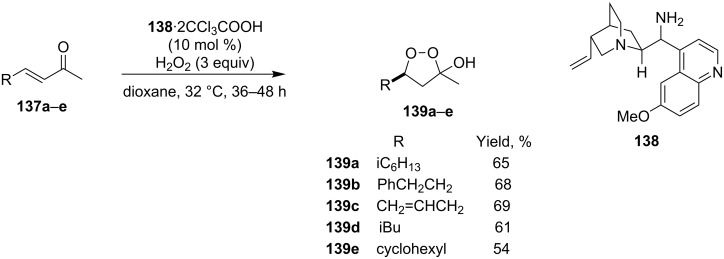

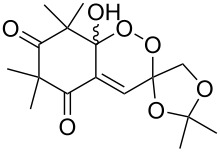

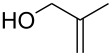

The asymmetric peroxidation of methyl vinyl ketones 137a–e with 9-amino-9-deoxyepiquinine 138 and CCl3COOH afforded hydroxydioxolanes 139a–e with high enantiomeric excess (ee 94–95%) (Scheme 32) [262].

Scheme 32.

Asymmetric peroxidation of methyl vinyl ketones 137a–e.

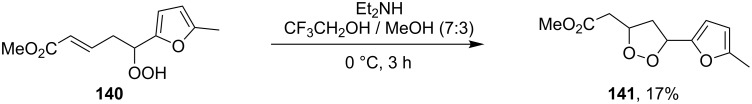

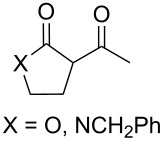

The Kobayashi synthesis of 1,2-dioxolanes represents an intramolecular version of the Michael reaction, in which the hydroperoxide group acts as the nucleophile. Generally, the reaction is performed in fluorinated alcohols (CF3CH2OH or (CF3)2CHOH) in the presence of diethylamine or, in some cases, of cesium hydroxide. Initially, the method was proposed for the synthesis of the 1,2-dioxane moiety (examples are considered in the corresponding section) [263]. However, it was shown that this method is also applicable to the preparation of structurally complex 1,2-dioxolanes, such as methyl 2-(5-(5-methylfuran-2-yl)-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)acetate (141) from the furan derivative (E)-methyl 5-hydroperoxy-5-(5-methylfuran-2-yl)pent-2-enoate (140) (Scheme 33) [264].

Scheme 33.

Et2NH-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization.

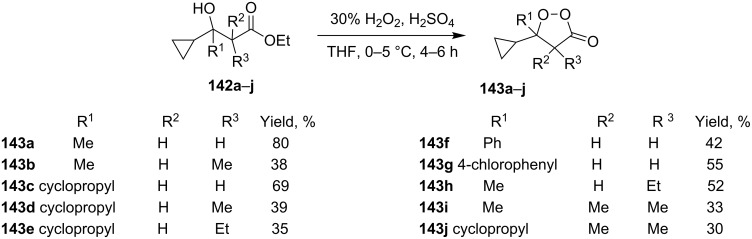

A simple method was developed for the synthesis of cyclopropane-containing oxodioxolanes 143a–j and is based on the hydroperoxidation of tertiary alcohols 142a–j in an acidic medium followed by cyclization of the intermediate hydroperoxides through the ester group (Scheme 34) [265].

Scheme 34.

Synthesis of oxodioxolanes 143a–j.

This method allows for the use of a nonhazardous 30% hydrogen peroxide solution. However, the authors mentioned that structurally similar tertiary alcohols, without a cyclopropane substituent, are inert under the reported conditions.

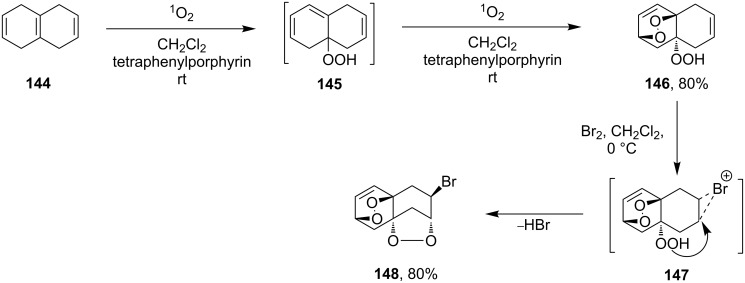

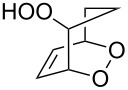

Haloperoxidation reaction that is accompanied by intramolecular ring closure represents another version of the cyclization reaction. For example, the reaction of bromine with unsaturated hydroperoxide 146 (produced by reaction of 1,4,5,8-tetrahydronaphthalene (144) with singlet oxygen via the formation of 4a-hydroperoxy-1,4,4a,5-tetrahydronapthalene (145) gives hydroperoxide-containing bromonium cation 147 as the intermediate, which undergoes cyclization to form 1,2-dioxolane-containing 7-bromo-4,5,10,11-tetraoxatetracyclo[7.2.2.13,6.03,9]tetradec-12-ene (148) (Scheme 35).

Scheme 35.

Haloperoxidation accompanied by intramolecular ring closure.

The cyclization occurs selectively because the hydroperoxide group in intermediate 147 attacks only one of two possible electrophilic carbon centers [266].

1.5. 1,2-Dioxolane ring formation through oxidation of the allylic position

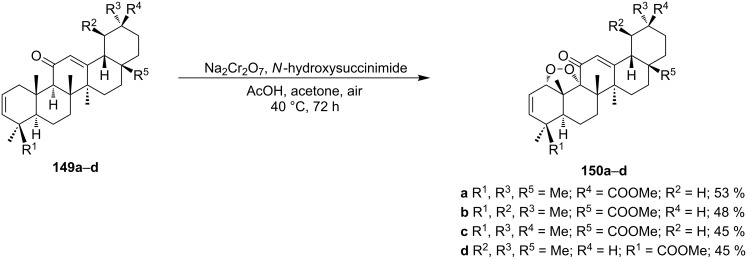

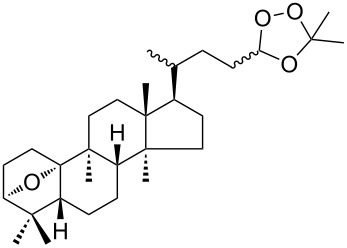

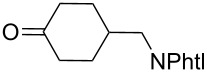

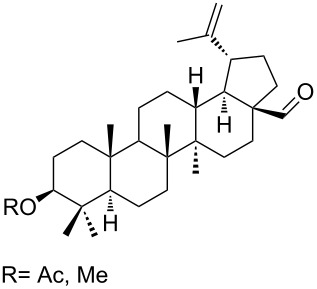

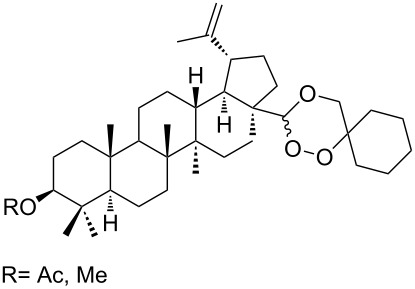

1,2-Dioxolane-containing compounds 150a–d were synthesized by the oxidation of triterpenes 149a–d with Na2Cr2O7/N-hydroxysuccinimide (Scheme 36). The resulting compounds exhibit antitumor activity comparable with that of betulinic acid [175–177].

Scheme 36.

Oxidation of triterpenes 149a–d with Na2Cr2O7/N-hydroxysuccinimide.

1.6. Structural modifications, in which the 1,2-dioxolane ring remains intact

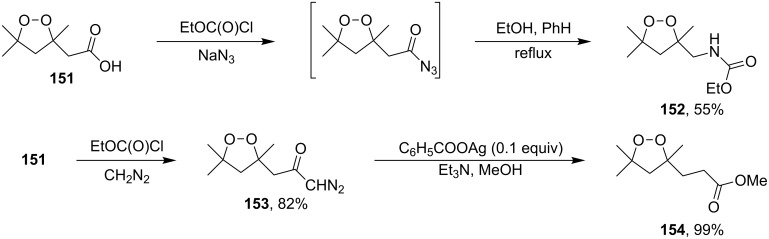

The possibility of performing the Curtius and Wolff rearrangements to form 1,2-dioxolane ring-retaining products was exemplified by the synthesis of ethyl (3,5,5-trimethyl-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)methylcarbamate (152) and methyl 3-(3,5,5-trimethyl-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)propanoate (154) (through formation of stable diazodioxolane 153) from 2-(3,5,5-trimethyl-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)acetic acid (151) (Scheme 37) [267].

Scheme 37.

Curtius and Wolff rearrangements to form 1,2-dioxolane ring-retaining products.

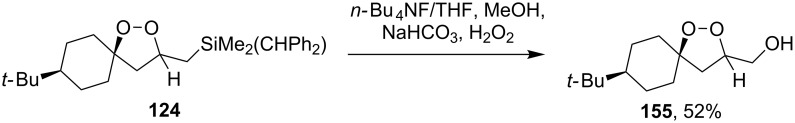

Dioxolane 155 that contains a free hydroxy group was synthesized by the oxidative desilylation of silicon-containing peroxide 124 with n-Bu4NF and H2O2 (Scheme 38) [259].

Scheme 38.

Oxidative desilylation of peroxide 124.

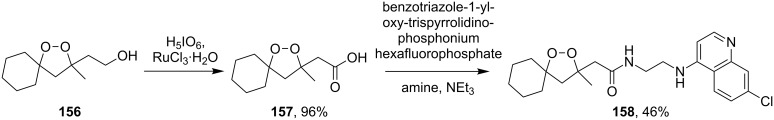

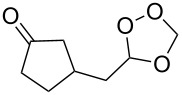

Dioxolane 158 with the aminoquinoline antimalarial pharmacophore was synthesized in two steps by the oxidation of alcohol 156 with H5IO6/RuCl3 followed by amidation of the acid 157 (Scheme 39) [88]. It was shown that compound 158 exhibits antimalarial activity comparable with that of artemisinin [88].

Scheme 39.

Synthesis of dioxolane 158, a compound containing the aminoquinoline antimalarial pharmacophore.

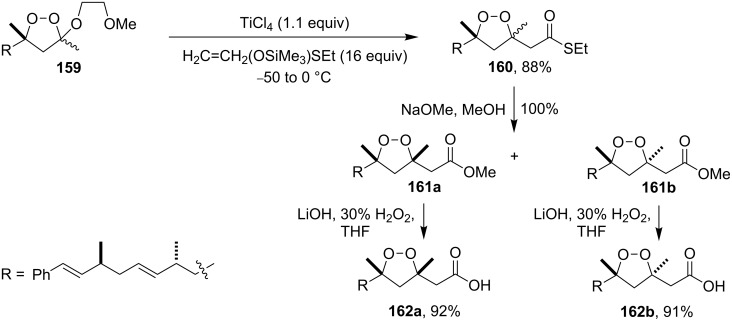

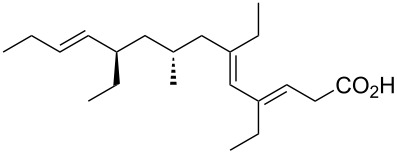

Plakinic acids belong to a large family of natural products, which were shown to be highly cytotoxic toward cancer cells and fungi. Diastereomers of plakinic acid A, 162a and 162b were synthesized starting from dioxolane ((R)-3-((2R,3E,6S,7E)-2,6-dimethyl-8-phenylocta-3,7-dienyl)-5-(2-methoxyethoxy)-3,5-dimethyl-1,2-dioxolane) (159) [260]. In the first step, dioxolane 159 was treated with (1-(ethylthio)vinyloxy)-trimethylsilane in the presence of TiCl4 to obtain S-ethyl 2-((R)-5-((2R,3E,6S,7E)-2,6-dimethyl-8-phenylocta-3,7-dienyl)-3,5-dimethyl-1,2-dioxolan-3-yl)-ethanethioate (160). The subsequent reaction with sodium methoxide in methanol produced the corresponding esters 161a and 161b, which were hydrolyzed to prepare the target plakinic acids (Scheme 40).

Scheme 40.

Diastereomers of plakinic acid A, 162a and 162b.

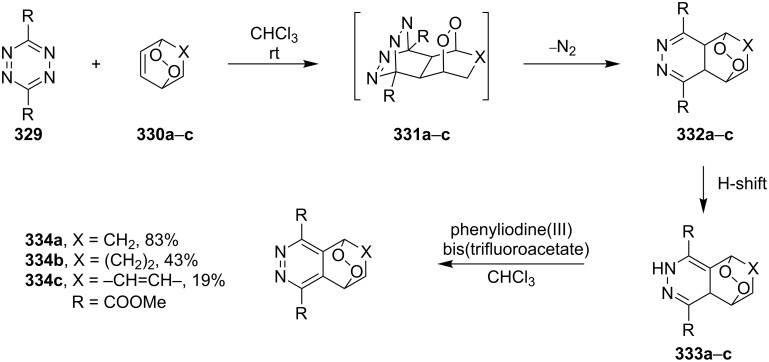

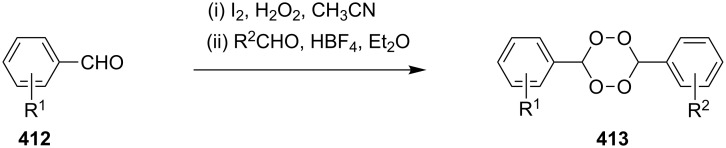

2. Synthesis of 1,2,4-trioxolanes (ozonides)

The currently most widely used methods for the synthesis of 1,2,4-trioxolanes are based on reactions of ozone with unsaturated compounds, such as the ozonolysis of alkenes, the cross-ozonolysis of alkenes with carbonyl compounds, and the cross-ozonolysis of О-alkylated oximes in the presence of carbonyl compounds (Griesbaum coozonolysis).

2.1. Ozonolysis of alkenes

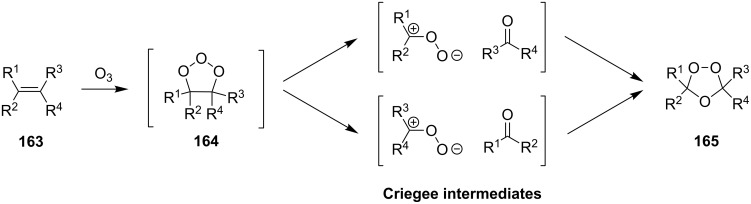

According to the mechanism proposed by R. Criegee [268–269] the ozonolysis of alkenes 163 involves several steps: the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of ozone to the double bond to form unstable 1,2,3-trioxolane 164 (so-called molozonide) that is followed by its decomposition to a peroxycarbenium ion and a carbonyl compound (Criegee intermediates). The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of the intermediates with each other form the 1,2,4-trioxolane 165 (Scheme 41, Table 11). Generally, the ozonolysis is performed in aprotic solvents at low temperatures and in some cases, on polymeric substrates. Since various compounds containing a С=С group are easily available, a wide range of functionalized 1,2,4-trioxolanes can be synthesized in moderate to high yields.

Scheme 41.

Ozonolysis of alkenes.

Table 11.

Examples of 1,2,4-trioxolanes produced by the ozonolysis of alkenes.

| Alkene 163 | Ozonolysis conditions | 1,2,4-Trioxolane 165 | Yield, % | Reference |

|

Et2O, −70 °C |  |

24 | [270] |

|

Et2O, −70 °C |  |

27 | [270] |

|

hexane, −78 °C |  |

78 | [256] |

|

hexane, −78 °C |  |

73 | [256] |

|

hexane, −78 °C |  |

77 | [256] |

|

hexane, −78 °C |  |

61 | [256] |

|

isooctane/CCl4, −78 °C, 1 h |  |

>82 | [271] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

95 | [272] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

90 | [272] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

92 | [272] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

93 | [272] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

93 | [272] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

94 | [272] |

|

pentane, −78 °C |

|

63 | [272] |

|

freon-113, 15–20 °C, 2 h |  |

The yield was not determined | [273–274] |

|

freon-113, 15–20 °C, 2 h |  |

The yield was not determined | [273] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

96 | [275] |

|

polymer-based, −78 °C, 8 h |  |

23 | [276] |

|

polymer-based, −78 °C, 3 h |  |

38 | [276] |

|

CH2Cl2, −70 °C |  |

48 | [277] |

|

without solvent, −133 to −43 °C |  |

100 | [278] |

|

1) CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 15 min. 2) Me2S, rt, 6 h |

|

71 | [279] |

|

hexane, −78 °C, 30 min |

|

6 | [280] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 20 min |  |

The yield was not determined | [281] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 2 h |  |

>97 | [282] |

|

CDCl3, −65 °C |  |

88 | [283] |

|

CFCl3, −70 °C |  |

100 | [283] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h |  |

85 | [284] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h |  |

70 | [285] |

|

pentane, −78 °C |

|

10-30 | [148–152] |

|

Et2O/CH3OH, −78 °C |  |

12 | [254] |

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |  |

92 | [286] |

|

CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

95 | [287–288] |

|

H2O/CH2Cl2, 0 °C |

|

72 | [289] |

|

1) SiO2, −78 °C; 2) Me2S, MeOH |

|

30 | [290] |

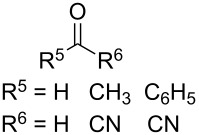

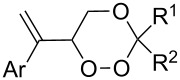

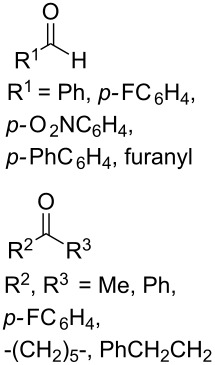

2.2. Cross-ozonolysis of alkenes with carbonyl compounds

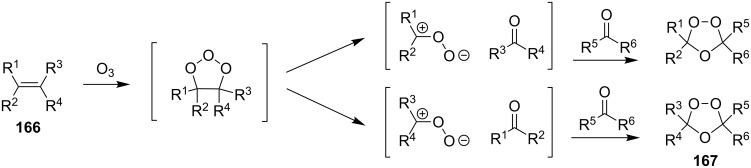

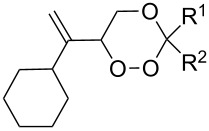

The peroxycarbenium ion produced by the decomposition of 1,2,3-trioxolane (molozonide) can react with externally introduced carbonyl compounds to form the corresponding 1,2,4-trioxolanes. The pathway of decomposition of 1,2,3-trioxolanes is determined by the structure of the starting alkene 166. In some cases, a high selectivity of the formation of cross-ozonolysis products 1,2,4-trioxolanes (ozonides) 167, can be achieved (Scheme 42, Table 12).

Scheme 42.

Cross-ozonolysis of alkenes 166 with carbonyl compounds.

Table 12.

Examples of 1,2,4-trioxolanes synthesized by the cross-ozonolysis of alkenes in the presence of carbonyl compounds.

| Alkene 166 | Carbonyl compound | Ozonolysis conditions | 1,2,4-Trioxolane 167 | Yield, % | Reference |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

17–74 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

9–57 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

50 42 |

[291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

38 32 |

[291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

18–48 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

25–37 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

63–80 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

55–77 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

49–74 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

63–66 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

52 62 |

[291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

41 46 |

[291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

82 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

26 | [291] |

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

58 53 |

[292] |

|

21 21 |

[292] | |||

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

23 25 |

[292] |

|

68 60 |

[292] | |||

|

|

CH2Cl2, −78 °C |

|

30 25 |

[292] |

|

15 14 |

[292] | |||

|

25 27 |

[292] | |||

|

|

Et2O, −70 °C |

|

60 56 |

[293] |

|

|

Et2O, −70 °C |

|

59 65 |

[293] |

|

|

Et2O, −70 °C |

|

59 | [293] |

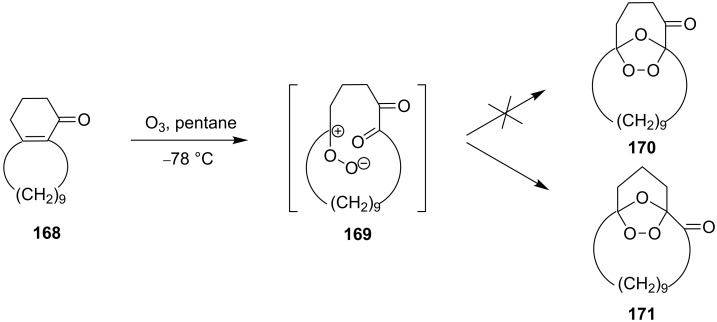

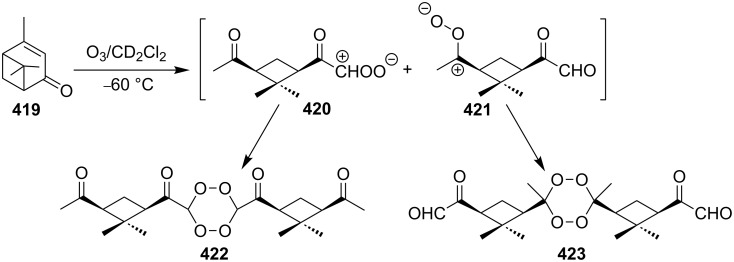

For the ozonolysis of the bicyclic cyclohexenone, 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15-tetradecahydro-1H-benzo[13]annulen-1-one (168), two reaction pathways can be proposed through intermediate 169 to form ozonides 170 and 171. It appeared that the reaction gave only 16,17,18-trioxatricyclo[10.3.2.11,12]octadecan-2-one 171 as two isomers, with the anti isomer in 60% and the syn isomer in 10% yield (Scheme 43) [294]. The structures of these compounds were established by X-ray diffraction [294].

Scheme 43.

Ozonolysis of the bicyclic cyclohexenone 168.

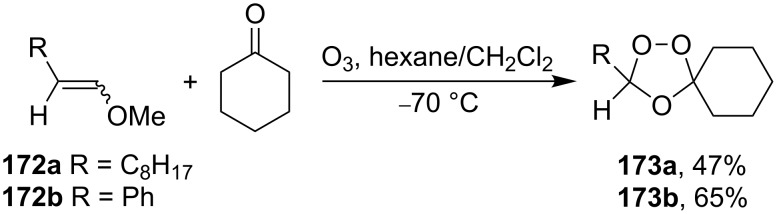

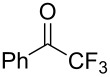

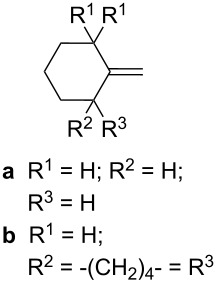

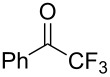

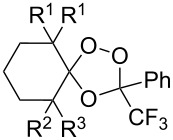

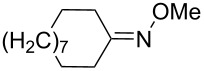

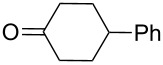

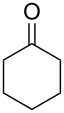

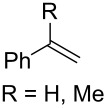

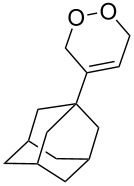

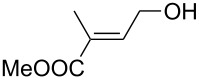

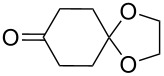

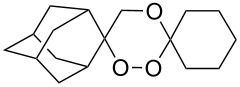

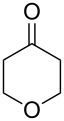

The cross-ozonolysis of enol ethers 172a,b with cyclohexanone enabled the synthesis of 1,2,4-trioxolanes 173a,b containing the easily oxidizable C–H fragment in the third position (Scheme 44) [256].

Scheme 44.

Cross-ozonolysis of enol ethers 172a,b with cyclohexanone.

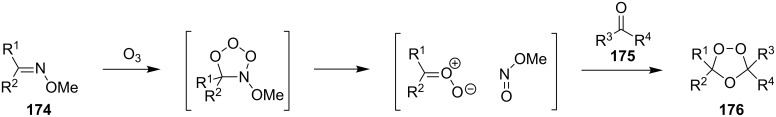

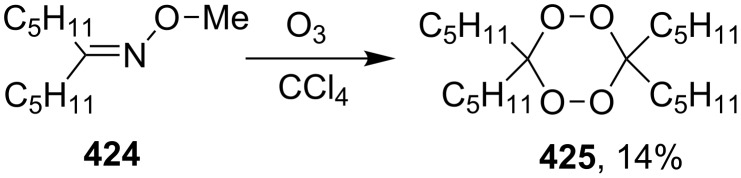

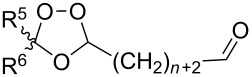

2.3. Cross-ozonolysis of O-alkyl oximes in the presence of carbonyl compounds (Griesbaum co-ozonolysis)

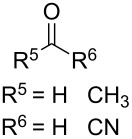

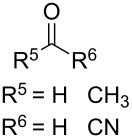

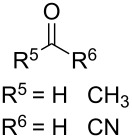

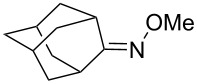

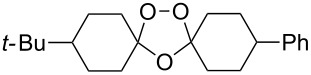

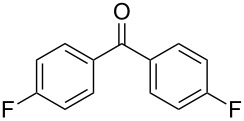

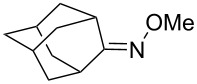

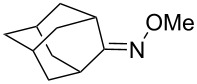

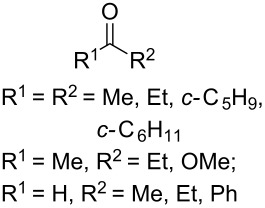

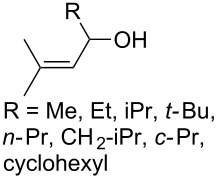

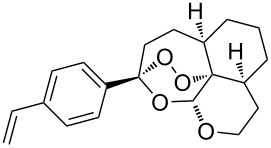

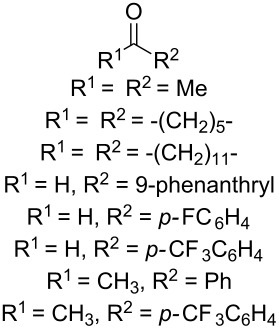

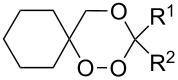

In 1995, K. Griesbaum and co-workers reported a new type of cross-ozonolysis [295]. This method enables the synthesis of tetrasubstituted ozonides 176 by an ozone-mediated reaction of О-alkyl oximes 174 with ketones 175 (Scheme 45, Table 13). The selective synthesis of ozonides has attracted great interest because it allows the preparation of compounds exhibiting high antiparasitic activity.

Scheme 45.

Griesbaum co-ozonolysis.

Table 13.

Examples of ozonides (1,2,4-trioxolanes) synthesized by the Griesbaum method.

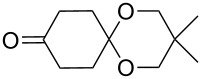

| Oxime 174 | Ketone 175 | Ozonolysis conditions | 1,2,4-Trioxolane 176 | Yield, % | Ref. |

|

|

hexane, −78 °C |  |

47–67 | [256] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

54 | [91] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

10–75 | [91,94] [95,296] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

23–50 | [91–93] |

|

|

pentane, 0 °C |  |

48 | [92–93] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

32–58 | [91–93] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

20–70 | [91–93,96] [97,297] |

|

|

pentane, 0 °C |  |

38 | [91] |

|

|

pentane, 0 °C |  |

41 | [91] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

33 | [91] |

|

|

hexane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |

|

17 | [91] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

27 | [91] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

53 | [92–93] |

|

|

pentane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

n.d.a | [96–97] |

|

|

cyclohexane CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

30 | [298] |

|

|

cyclohexane CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

54 | [298] |

|

|

cyclohexane, CH2Cl2, 0 °C |  |

78 | [258] |

aYield was not determined

The Griesbaum method is widely applicable and allows the selective synthesis of symmetrical and unsymmetrical 1,2,4-trioxolanes, which are not accessible by direct ozonolysis of alkenes or the cross-ozonolysis of alkenes or enol ethers in the presence of carbonyl compounds. In addition, this method does not need tetrasubstituted alkenes or enol ethers as starting materials, which are difficult to prepare. Taking into account a wide range of commercially available ketones, it can be concluded that this is the most universal method for the synthesis of 1,2,4-trioxolanes in terms of selectivity and structural diversity of the final products.

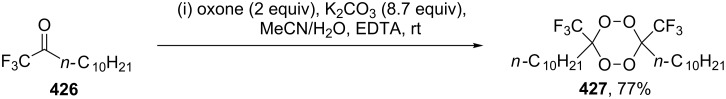

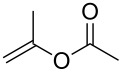

2.4. Other methods for the synthesis of 1,2,4-trioxolanes

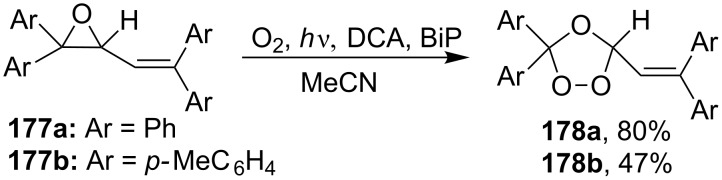

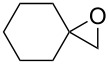

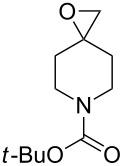

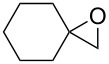

The reactions of aryloxiranes 177a,b with oxygen in the presence of 9,10-dicyanoanthracene (DCA) and biphenyl (BiP) under irradiation produced 1,2,4-trioxolanes 178a and 178b (Scheme 46). It should be noted that the oxirane moiety is oxidized rather than the double bond in these reactions [299].

Scheme 46.

Reactions of aryloxiranes 177a,b with oxygen.

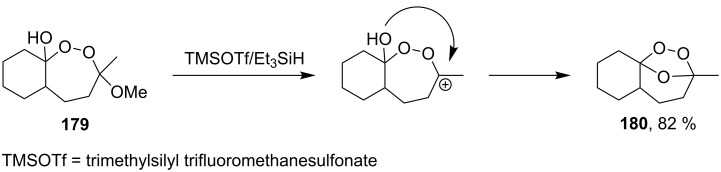

This unusual result was obtained upon treatment of the hydroxydioxepane, 3-methoxy-3-methyloctahydro-3H-benzo[c][1,2]dioxepin-9a-ol (179) with TMSOTf/Et3SiH. Thus, the peroxide moiety was not reduced with Et3SiH, and the reaction produced the bicyclic peroxide, 1-methyl-10,11,12-trioxatricyclo[7.2.1.04,9]dodecane (180) containing the 1,2,4-trioxolane moiety, as the major product (Scheme 47) [270].

Scheme 47.

Intramolecular formation of 1,2,4-trioxolane 180.

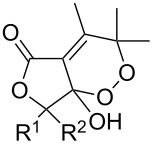

The same bicyclic peroxide 180 was synthesized in good yield by the reaction of 2-(2-(2-methyl-1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)ethyl)cyclohexanone (181) with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of phosphomolybdic acid (PMA) (Scheme 48) [300].

Scheme 48.

Formation of 1,2,4-trioxolane 180 by the reaction of 1,5-ketoacetal 181 with H2O2.

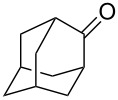

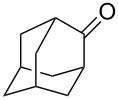

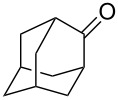

2.5. Structural modifications, in which 1,2,4-trioxolane ring remains intact

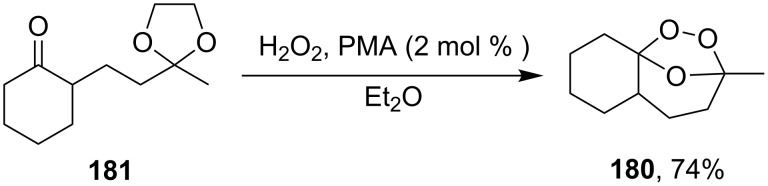

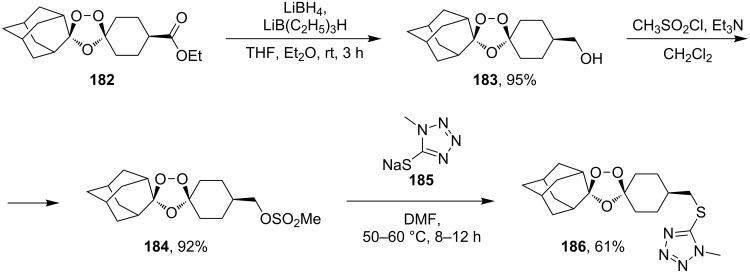

Scheme 49 shows possible modifications of substituents at the ozonide ring by the reduction of the ester group in cis-adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-ethoxycarbonyl-1’,2’,4’-trioxa-spiro[4.5]decane 182 to form the alcohol cis-adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-hydroxymethyl-1’,2’,4’-trioxaspiro[4.5]decane 183. The latter was mesylated to 184 (cis-adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-methanesulfonylmethyl-1’,2’,4’-trioxa-spiro[4.5]decane), and used in the reaction with sodium 1-methyl-1H-tetrazole-5-thiolate 185 for the synthesis of cis-adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-[[(1’-methyl-1’H-tetrazol-5’-yl)thio]methyl]-1’,2’,4’-trioxaspiro[4.5]decane 186 through nucleophilic substitution of the mesyl group by the thio group of tetrazole 185 (Scheme 49) [297].

Scheme 49.

1,2,4-Trioxolane 186 with tetrazole fragment.

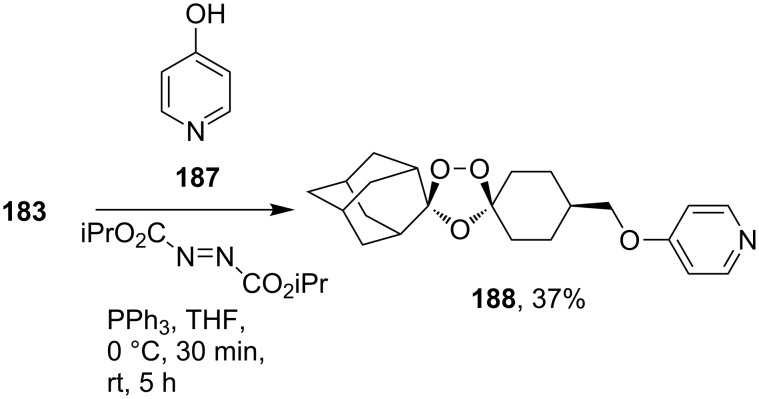

Ozonide 188 was synthesized by Mitsunobu reaction of alcohol 183 with pyridin-4-ol (187) (Scheme 50) [93]. It should be emphasized that this method can be applied in spite of the use of triphenylphosphine, which is a strong reducing agent for peroxides.

Scheme 50.

1,2,4-Trioxolane 188 with a pyridine fragment.

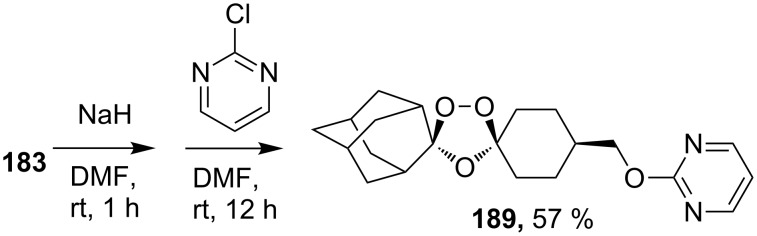

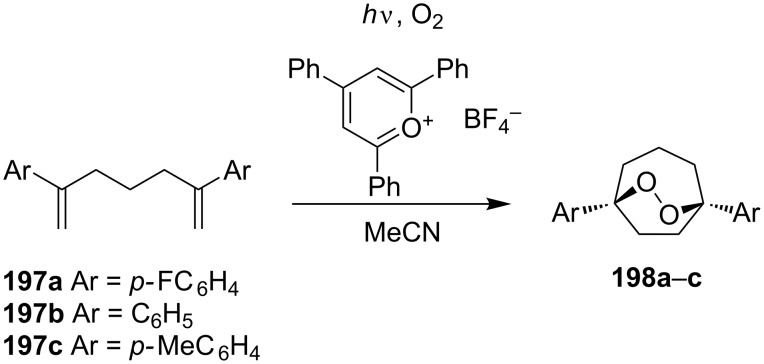

The alkylation of the sodium salt of alcohol 183 with 2-chloropyrimidine in dimethylformamide gave ozonide 189 (Scheme 51). In this reaction, neither sodium hydride nor sodium salt 183 cleave the ozonide ring to a substantial degree. The resulting 1,2,4-trioxolanes 188 and 189 exhibit high in vitro antimalarial activity comparable with that of artemisinin and in vivo even higher activity than that of artemisinin [93].

Scheme 51.

1,2,4-Trioxolane 189 with pyrimidine fragment.

Aminoquinoline-containing 1,2,4-trioxalane 191 was synthesized by reductive amination of adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-oxo-1’,2’,4’-trioxaspiro[4.5]-decane 190 (Scheme 52). Ozonide 191 is an example of a combination of two known antiparasitic pharmacophores, viz. a peroxide and an aminoquinoline moiety [296].

Scheme 52.

Synthesis of aminoquinoline-containing 1,2,4-trioxalane 191.

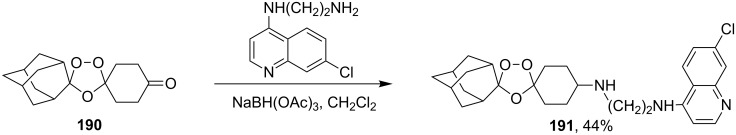

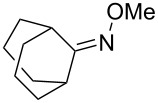

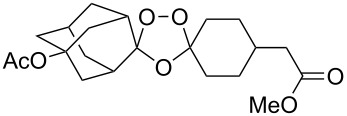

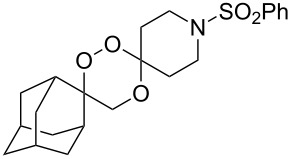

Arterolane is a fully synthetic 1,2,4-trioxalane, also known as OZ277. It has high antimalarial activity and is currently in the final stage of clinical trials. As drug, this compound is used in combination with piperaquine. The synthesis of arterolane is based on the Griesbaum coozonolysis of a mixture of adamantan-2-one O-methyloxime (192) and 4-carbomethoxycyclohexanone 193 to form cis-adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-methoxycarbonylmethyl-1’,2’,4’-trioxaspiro[4.5]decane 194. The latter is hydrolyzed to cis-adamantane-2-spiro-3’-8’-carboxymethyl-1’,2’,4’-trioxaspiro[4.5]decane 195, followed by mild amidation with the formation of the intermediate ozonide 196 that on treatment with 2-methylpropane-1,2-diamine finally gives the target compound (Scheme 53). The in vitro and in vivo studies showed that arterolane is more active against causative agents of malaria than artemisinin, chloroquine, and mefloquine [77–78,81].

Scheme 53.

Synthesis of arterolane.

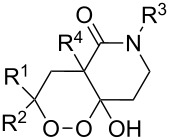

3. Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes

Modern approaches to the synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes are based on reactions with singlet oxygen, the oxidative coupling of carbonyl compounds and alkenes in the presence of manganese and cerium salts, the co-oxidation of alkenes and thiols with oxygen, the Isayama–Mukaiyama peroxidation, the Kobayashi cyclization of hydroperoxides, the reaction of 1,4-diketones with hydrogen peroxide, the intramolecular nucleophilic substitution by the hydroperoxide group, the cyclization with participation of halogenonium ion donors, acid-mediated rearrangements of peroxides, the palladium-catalyzed cyclization of compounds with С=С and –О–О– groups, and reactions with the participation of peroxycarbenium ions.

3.1. Methods for the synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes using singlet oxygen

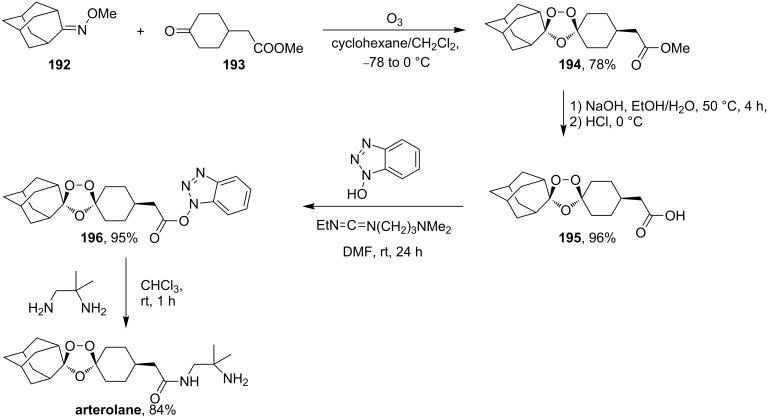

The oxidation of diarylheptadienes 197a–c with singlet oxygen in acetonitrile afforded bicyclic peroxides 198a–c in 33–58% yields. 2,4,6-Triphenylpyrylium tetrafluoroborate was used as the sensitizer for singlet oxygen generation (Scheme 54) [301].

Scheme 54.

Oxidation of diarylheptadienes 197a–c with singlet oxygen.

It was found that tris(bipyrazyl)ruthenium(II) [(Ru(bpz)3(PF6)2] is an excellent photocatalyst for the synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes by aerobic photooxygenation of α,ω-dienes [302].

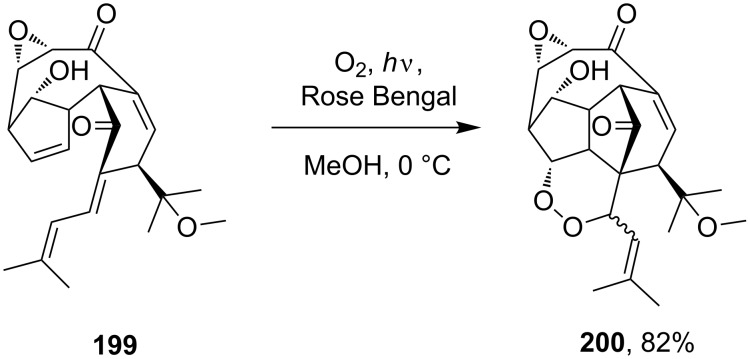

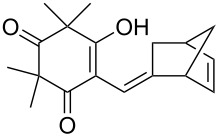

The addition of singlet oxygen to substrate 199 occurs in the last step of the synthesis of natural hexacyclinol peroxide 200 (Scheme 55) [303].

Scheme 55.

Synthesis of hexacyclinol peroxide 200.

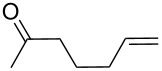

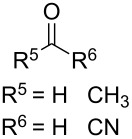

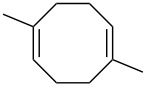

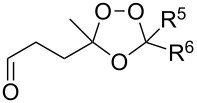

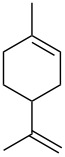

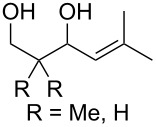

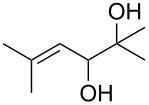

The reactions of 6-methylhept-5-en-2-one (201) and 5-methylhex-4-enenitrile (203) with singlet oxygen produced 1,2-dioxanes, 3-methyl-6-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-1,2-dioxan-3-ol (202) and 6-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-1,2-dioxane-3-imine (204), containing the hydroxy and imine groups, respectively (Scheme 56) [304].

Scheme 56.

Oxidation of enone 201 and enenitrile 203 with singlet oxygen.

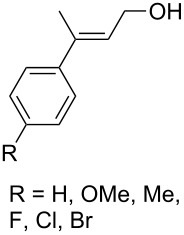

3.2. Oxidative coupling of carbonyl compounds and alkenes in the presence of manganese or cerium salts

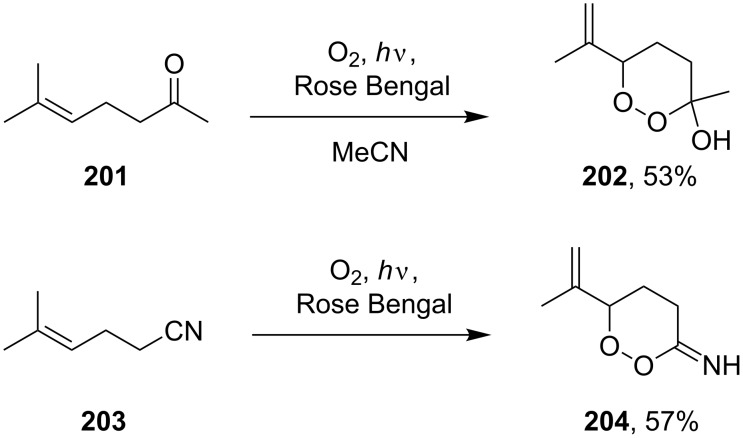

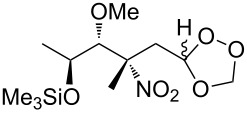

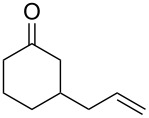

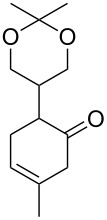

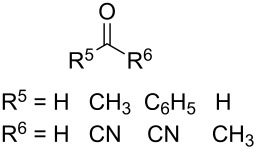

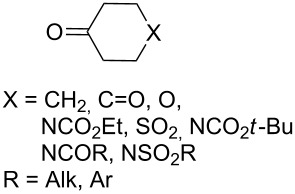

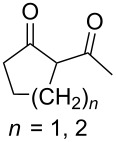

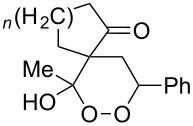

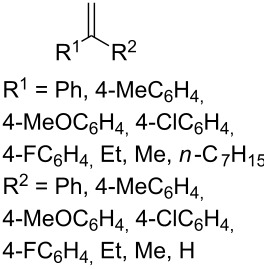

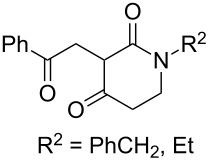

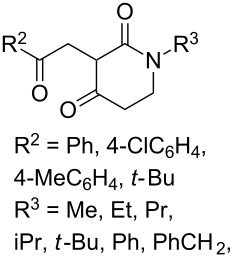

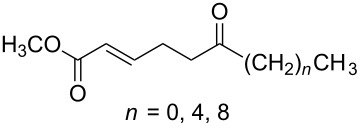

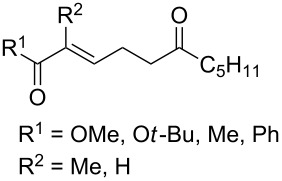

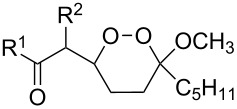

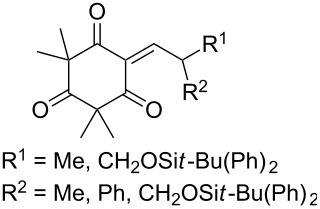

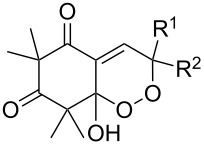

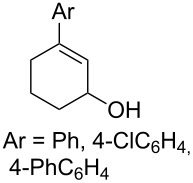

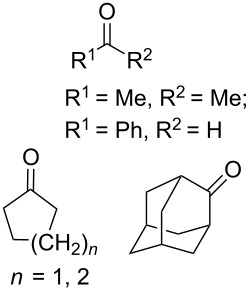

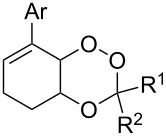

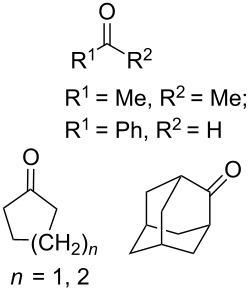

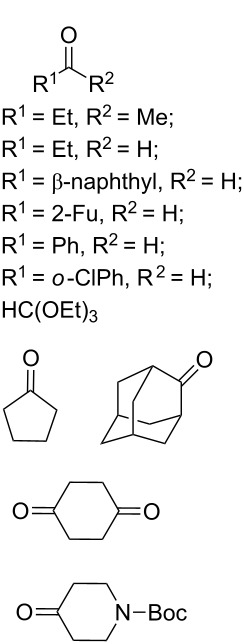

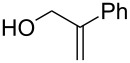

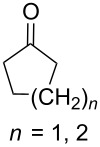

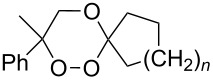

The synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes 207 is based on the addition of alkene 205 and oxygen to carbonyl compound 206 via the intermediate formation of carbon-centered peroxide radicals. The reaction occurs in the presence of catalytic amounts of manganese or cerium salts, which are involved in a redox cycle. It is assumed that the oxidation of β-dicarbonyl compounds proceeds through a formation of an enol-containing complex with a metal ion (Scheme 57, Table 14).

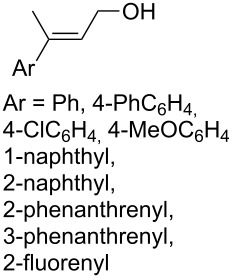

Scheme 57.

Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes 207 by oxidative coupling of carbonyl compounds 206 and alkenes 205.

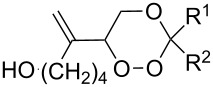

Table 14.

Examples of 1,2-dioxanes 207 synthesized by oxidative coupling of carbonyl compounds 206 and alkenes 205.

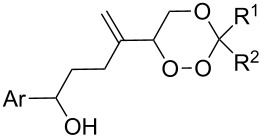

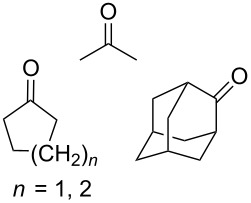

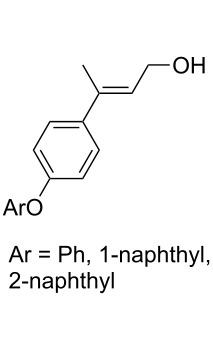

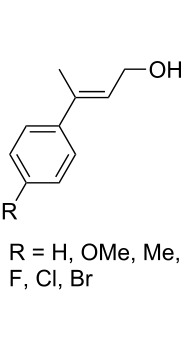

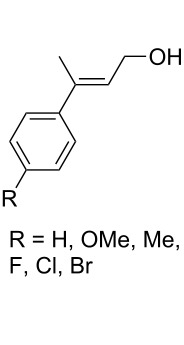

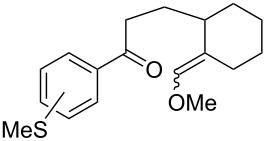

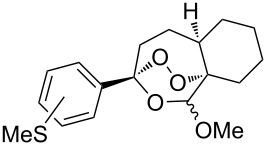

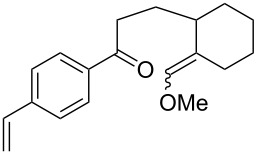

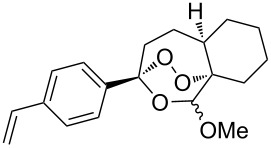

| Alkene 205 | Carbonyl compound 206 | Reaction conditions | 1,2-Dioxane 207 | Yield, % | Ref. |

|

|

Mn(OAc)2, O2, AcOH, 80 °C, 10 h |

|

67 | [305] |

|

|

Mn(OAc)3, air, AcOH, 23 °C, 0.5–24 h |  |

20–84 | [306] |

|

|

CeCl3×7H2O, air, iPrOH, rt, 16 h |  |

42–87 | [307] |

|

|

CeCl3×7H2O, air, iPrOH, rt, 16 h |  |

5–73 | [307] |

|

|

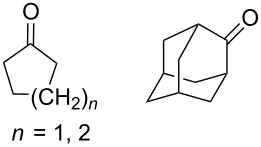

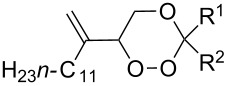

CeCl3×7H2O, air, iPrOH, rt, 14–16 h |

|

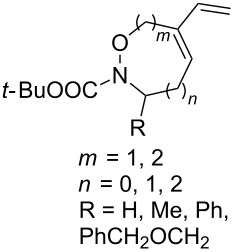

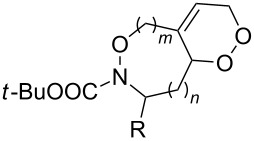

19 (n = 1), 33 (n = 2) |

[308] |

|

|

CeCl3×7H2O, air, iPrOH, rt, 14–16 h |

|

18 | [308] |

|

|

Mn(OAc)3, air, AcOH, 23 °C, 15–18 h |  |

22–89 | [309] |

|

|

Mn(OAc)3, air, AcOH, 23 °C, 9–18 h |  |

17–99 | [310] |

|

|

Mn(OAc)3, air, AcOH, reflux, 10 min |  |

9–11 | [311] |

|

|

Mn(OAc)3, air, AcOH, rt, 3.5–7.5 h |  |

8–75 | [312] |

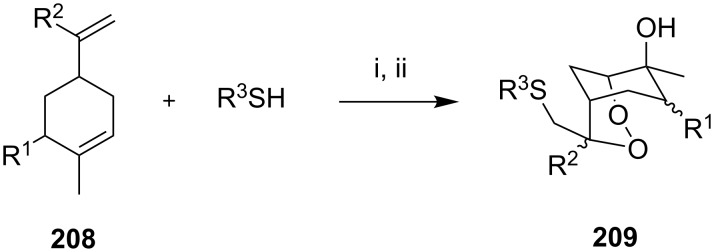

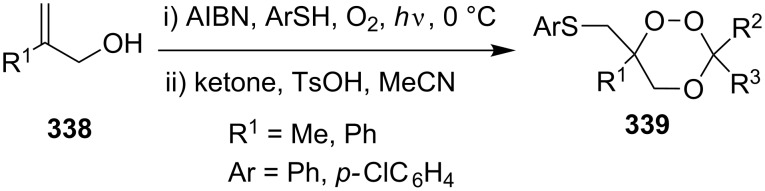

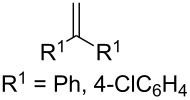

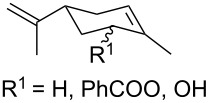

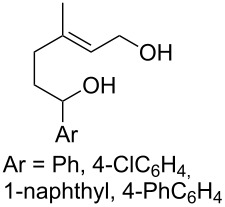

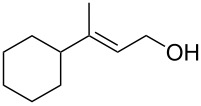

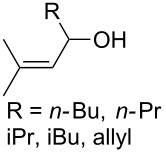

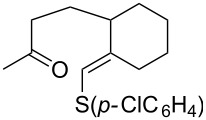

3.3. Oxidation of 1,5-dienes in the presence of thiols

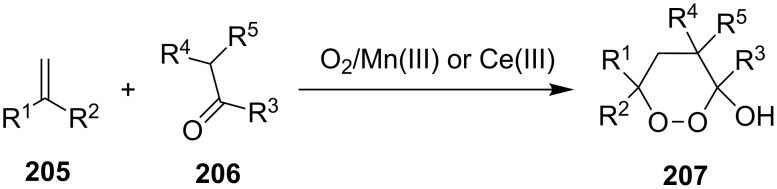

The co-oxidation of 1,4-dienes and thiols (thiol–olefin co-oxygenation, TOCO reaction) was described for the first time by Beckwith and Wagner as a method for the synthesis of sulfur-containing 1,2-dioxolanes [313–314]. More recently, it has been shown that under similar conditions, the oxidation of 1,5-dienes 208 affords the corresponding sulfur-containing 1,2-dioxanes 209. The reaction proceeds under oxygen atmosphere in the presence of azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) or ditert-butyl peroxalate (DBPO) as radical initiators. The resulting unstable hydroperoxides are reduced with triphenylphosphine to hydroxy derivatives 209 (Scheme 58, Table 15).

Scheme 58.

1,2-Dioxanes 209 synthesis by co-oxidation of 1,5-dienes 208 and thiols.

Table 15.

Examples of 1,2-dioxanes synthesized by co-oxidation of 1,5-dienes and thiols.

| Diene 208 | Thiol | Reaction conditions | 1,2-Dioxane 209 | Yield, % | Reference |

|

R3SH R3 = Ph, 4-FC6H4, n-Bu, t-Bu, MeO2CCH2, cyclohexyl, Ph3C |

1) O2, DBPO, benzene/heptane, rt, 10 h or O2, AIBN, hν, MeCN, 4 °C, 10 h 2) Ph3P, CH2Cl2, 0–5 °C, 2 h, rt, 1 h |

|

6–54 | [107,179,315] |

|

PhSH 4-ClC6H4SH |

1) O2, AIBN, hν, MeCN, 0 °C, 2 h 2) Ph3P, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt |

|

70 (Ar = Ph), 21 (Ar = 4-ClC6H4) |

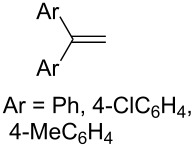

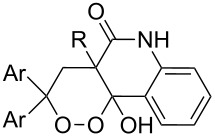

[102,316] |

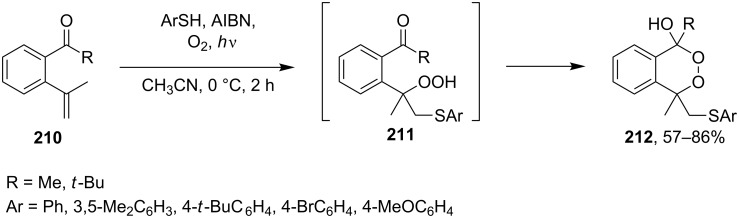

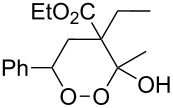

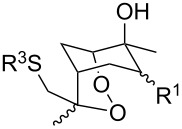

The oxidation of acetophenones 210 produces bicyclic 1,2-dioxanes 212 (Scheme 59). It is hypothesized that the reaction gives hydroperoxide 211 as the intermediate, that undergoes rapid cyclization to form the target 1,2-dioxane 212 [317].

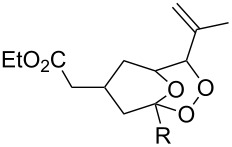

Scheme 59.

Synthesis of bicyclic 1,2-dioxanes 212 with aryl substituents.

3.4. Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes by the Isayama–Mukaiyama method

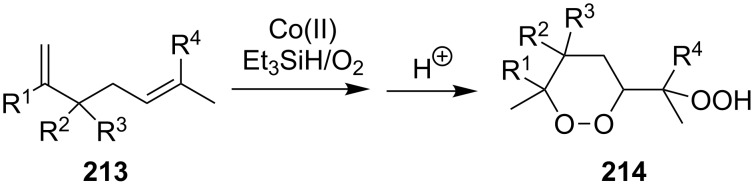

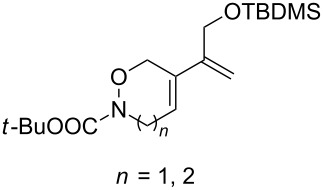

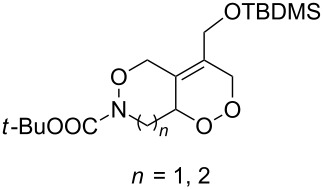

The Isayama–Mukaiyama peroxysilylation of 1,5-dienes 213 followed by desilylation under acidic conditions gives hydroperoxide-containing 1,2-dioxanes 214 (Scheme 60, Table 16).

Scheme 60.

Isayama–Mukaiyama peroxysilylation of 1,5-dienes 213 followed by desilylation under acidic conditions.

Table 16.

Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes by the Isayama–Mukaiyama method.

| 1,5-Diene 213 | Reaction conditionsa | 1,2-Dioxane 214 | Yield, % | Reference |

|

1) Co(modp)2, O2, Et3SiH, ClCH2CH2Cl, 2–6 h 2) HCl/MeOH |

|

13–64 | [249] |

|

1) Co(modp)2, O2, Et3SiH, ClCH2CH2Cl, 1 h 2) HCl/MeOH |

|

22 | [318–319] |

amodp = 1-morpholino-5,5-dimethyl-1,2,4-hexanetrionate.

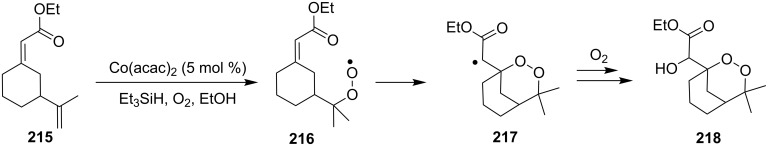

The oxidation of (Z)-ethyl 2-(3-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohexylidene)acetate (215) gives ethyl 2-(4,4-dimethyl-2,3-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-1-yl)-2-hydroxyacetate (218) in 29% yield. The oxidative reaction proceeds presumably with formation of an O-centered radical 216, then a C-centered radical 217 and the latter adds oxygen and is reduced to the hydroxy derivative of 1,2-dioxane 218 (Scheme 61) [318].

Scheme 61.

Synthesis of bicycle 218 with an 1,2-dioxane ring.

An alternative synthesis of a 1,2-dioxane by the Isayama–Mukaiyama method includes the following sequence of reactions: peroxysilylation, desilylation, and recyclization accompanied by a ring opening of oxirane or oxetane (Scheme 62 and Scheme 63).

Scheme 62.

Intramolecular cyclization with an oxirane-ring opening.

Scheme 63.

Inramolecular cyclization with the oxetane-ring opening.

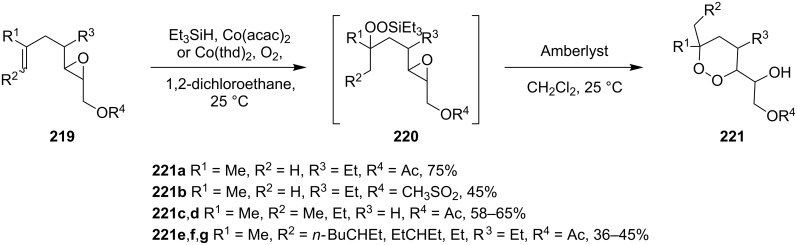

Cobalt(II) acetylacetonate (acac) or bis-2,2,6,6-tetramethylheptane-3,5-dienoate (thd) were used as the catalyst for the peroxidation of 219. The cyclization of the intermediate peroxide 220 was performed with Amberlyst-15 ion-exchange resin. This approach was used in the multistep synthesis of the natural endoperoxide 9,10-dihydroplakortin, which exhibits antimalarial and anticancer activities as do its structural analogues [320–321].

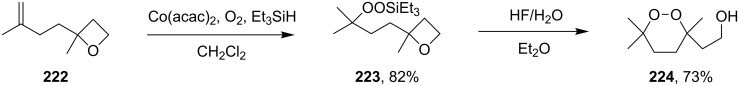

2-(3,6,6-Trimethyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)ethanol (224) was synthesized in a similar way starting with the peroxidation of 2-methyl-2-(3-methylbut-3-enyl)oxetane (222), followed by oxetane-ring opening in triethyl(2-methyl-4-(2-methyloxetan-2-yl)butan-2-ylperoxy)silane (223) (Scheme 63) [250].

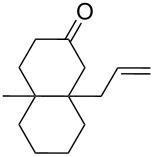

Dioxanes can also be synthesized by inramolecular cyclizations with the attack on a keto group. The peroxysilylation of the unsaturated ketone 1,5-dicyclohexenylpentan-3-one (225), with the Co(thd)2/Et3SiH/O2 system produced 1,5-bis(1-(triethylsilylperoxy)cyclohexyl)pentan-3-one (226), which underwent cyclization in the presence of p-toluenesulfonic acid to give the spiro-fused 7,8,10,11-tetraoxatrispiro[5.2.2.5.2.2]henicosane 227 (Scheme 64) [252].

Scheme 64.

Intramolecular cyclization with the attack on a keto group.

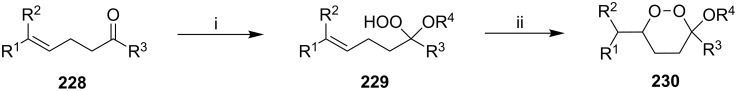

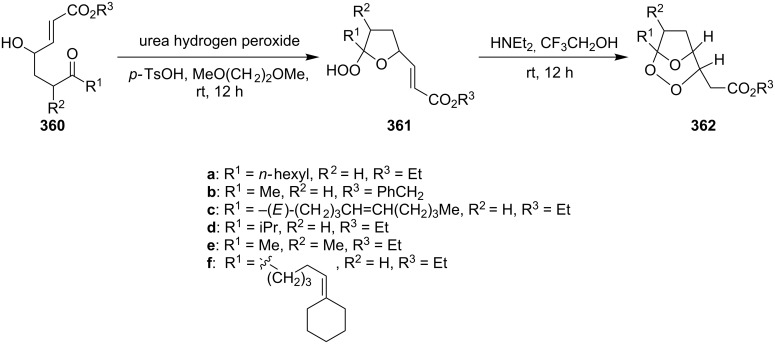

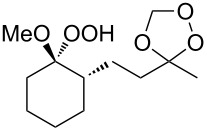

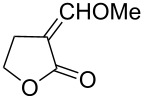

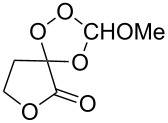

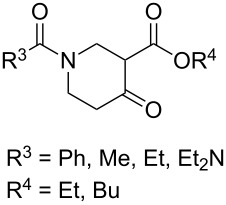

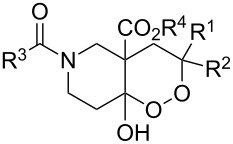

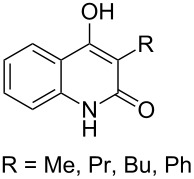

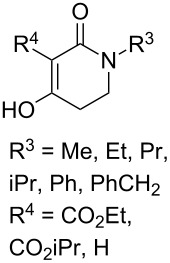

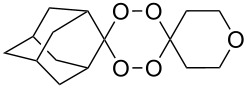

3.5. Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes by the Kobayashi method

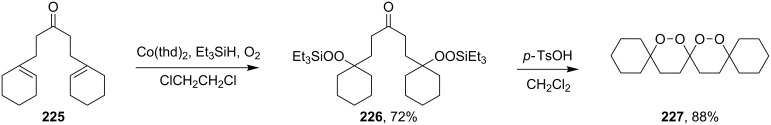

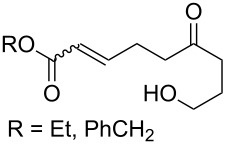

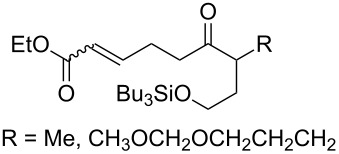

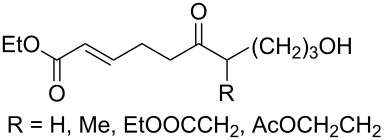

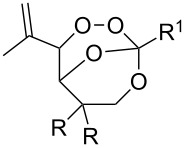

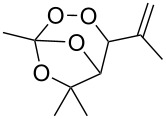

The synthesis is based on the peroxidation of the carbonyl group of unsaturated ketones 228 with the urea–hydrogen peroxide complex followed by a Michael cyclization of the hydroperoxy acetals 229 under basic conditions. This method is suitable for the efficient synthesis of functionalized 1,2-dioxanes 230 in moderate to high yields (Scheme 65, Table 17). In early studies, scandium(III) triflate was used as the catalyst for the hydroperoxidation of ketones with the H2O2–H2NCONH2 complex. More recently, it was shown that in some cases, cheaper catalysts such as p-toluenesulfonic and 10-camphorsulfonic acid can be used for this purpose (Table 17).

Scheme 65.

Peroxidation of the carbonyl group in unsaturated ketones 228 followed by cyclization of hydroperoxy acetals 229.

Table 17.

Examples of 1,2-dioxanes synthesized by the Kobayashi method.

| Unsaturated ketone 228 | Reaction conditions | 1,2-Dioxane 230 | Yield, % | Reference |

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, Sc(OTf)3, MeOH 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH, 0 °C, 2 d |

|

1) 67–83 2) 60–72 |

[322–323] |

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, Sc(OTf)3, MeOH 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH 3) HF, pyridine, THF |

|

1) 52 2) 87 3) 100 |

[324] |

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, Sc(OTf)3, MeOH 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH |

|

8–38 | [104–106] |

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, Sc(OTf)3, MeOH 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH |

|

28–58 | [104–106] |

Intermediate product 229 has the following structure:

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, p-TsOH, MeOH, rt, 20 h 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH, rt, 24 h |

|

1) 54–82 2) 52 |

[325–327] |

|

H2O2–H2NCONH2, p-TsOH, 1,2-dimethoxyethane, rt, 11 h |  |

35 | [325–327] |

Intermediate product 229 has the following structure:

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, 10-camphorsulfonic acid, 1,2-dimethoxyethane, rt, 18 h 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH, rt, 2 h |

|

1) 86 2) 54 |

[325–327] |

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, p-TsOH, EtOH, rt, 10 h 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH, rt, 12 h |

|

1) 72–80 2) 40–52 |

[328] |

|

1) H2O2.H2NCONH2, p-TsOH, EtOH, rt, 12 h 2) Et2NH, CF3CH2OH, rt |

|

1) 70–93 2) 42–65 |

[328] |

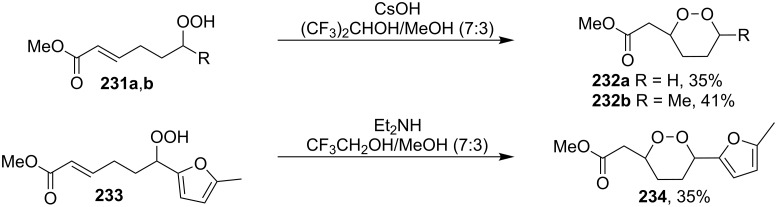

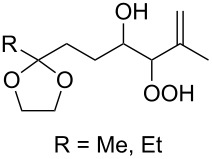

It was found that cesium hydroxide can be used as a base for the cyclization to give 232 and 234. Compared to Scheme 65, the method is suitable for the cyclization of hydroperoxides 231 and 233, which are no ketone derivatives (Scheme 66) [264]. Et3N in MeOH can also be used as catalyst for this type of cyclization [263].

Scheme 66.

CsOH and Et2NH-catalyzed cyclization.

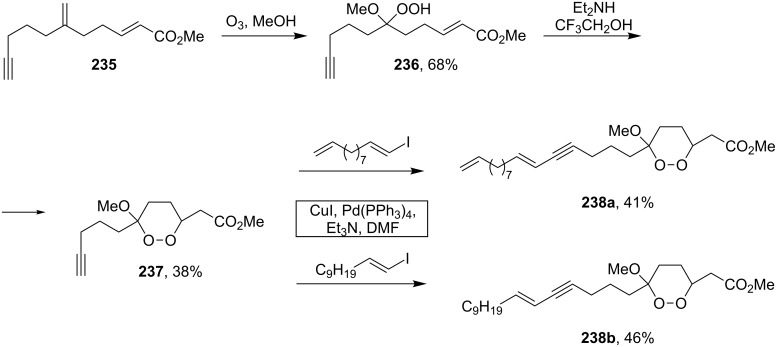

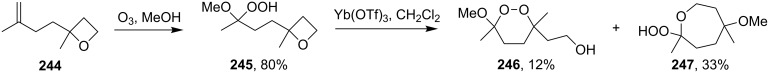

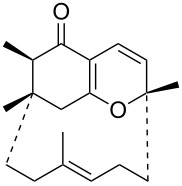

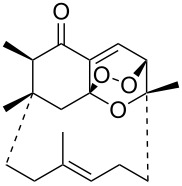

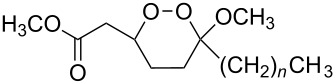

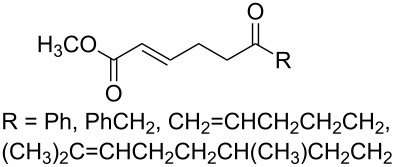

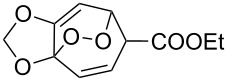

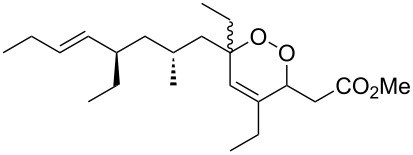

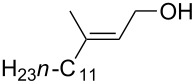

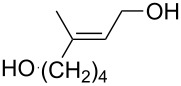

The synthesis of peroxyplakoric acid methyl ethers A and D 238a and 238b, which are natural peroxides isolated from marine sponges exhibiting fungicidal and antitumor activities [329–330] is an interesting example of the synthesis of complex structures. The polyunsaturated compound (E)-methyl 6-methyleneundec-2-en-10-ynoate (235) was subjected to ozonolysis to obtain methoxyhydroperoxide, (E)-methyl 6-hydroperoxy-6-methoxyundec-2-en-10-ynoate (236), whose cyclization afforded methyl 2-(6-methoxy-6-(pent-4-inyl)-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)acetate (237), in which the triple bond is easily modified by palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions to form the target 1,2-dioxanes 238a,b (Scheme 67).

Scheme 67.

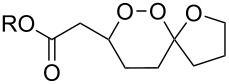

Preparation of peroxyplakoric acid methyl ethers A and D.

Initially, an attempt was made to synthesize diethyl 2,2'-(1,2,7,8-tetraoxaspiro[5.5]undecane-3,9-diyl)diacetate (241) by cyclization of (2E,9E)-diethyl 6,6-dihydroperoxyundeca-2,9-dienedioate bis(hydroperoxide) (240) (the bishydroperoxidation product of (2E,9E)-diethyl 6,6-dimethoxyundeca-2,9-dienedioate (239)) with Et2NH in CF3CH2OH. However, these attempts failed. Spiroperoxide 241 was prepared in satisfactory yield by reaction of 240 with the use of mercury (II) acetate (Scheme 68) [331]. The intermediate mercury-containing peroxide produced by the cyclization of bis(hydroperoxide) 240 was reduced with NaBH4 in an alkaline medium [331].

Scheme 68.

Hg(OAc)2 in 1,2-dioxane synthesis.

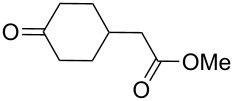

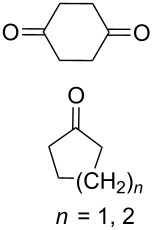

3.6. Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes from 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds

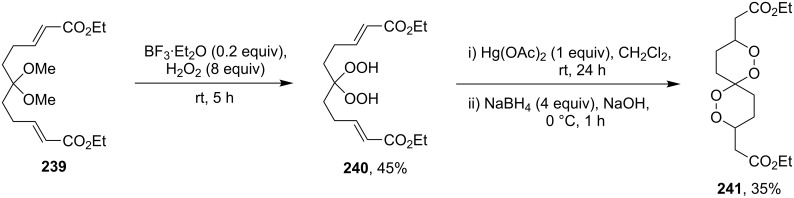

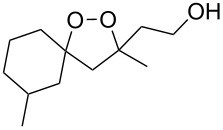

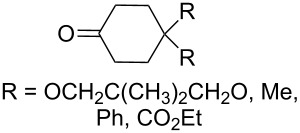

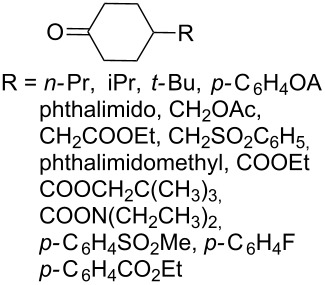

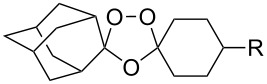

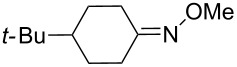

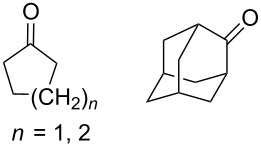

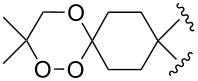

The reaction of 1,4-diketones 242 (cyclohexanone derivatives) with hydrogen peroxide in a neutral medium produced 3,6-dihydroxydioxanes 243 albeit without reported yields (Scheme 69). The resulting compounds exhibit a broad spectrum of antiparasitic activities against causative agents of malaria, trypanosomiasis, and leishmaniasis [208–212].

Scheme 69.

Reaction of 1,4-diketones 242 with hydrogen peroxide.

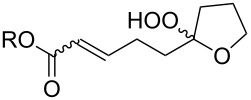

3.7. Methods for the synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes from hydroperoxides

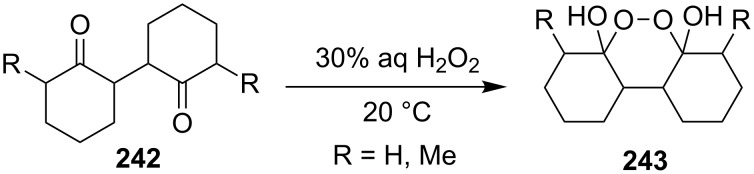

Compounds containing a С=С group and an oxygen-containing ring are convenient starting materials for the synthesis of cyclic peroxides [250–252,332]. For example, the ozonolysis of the double bond in the oxetane-containing compound, 2-methyl-2-(3-methylbut-3-enyl)oxetane (244) afforded 2-(3-hydroperoxy-3-methoxybutyl)-2-methyloxetane (245), which underwent recyclization in the presence of ytterbium triflate to give 2-(6-methoxy-3,6-dimethyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)ethanol (246) along with the seven-membered compound 2-hydroperoxy-5-methoxy-2,5-dimethyloxepane (247) (Scheme 70) [250].

Scheme 70.

Inramolecular cyclization with oxetane-ring opening.

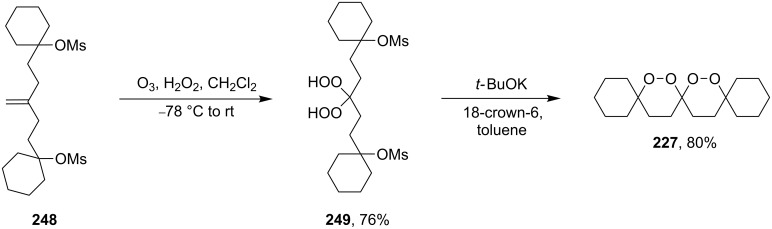

Spirodioxane 227, whose synthesis by the Isayama–Mukaiyama method was described above (Scheme 64), could also be synthesized via the ozonolysis of alkene 248 in the presence of hydrogen peroxide followed by the cyclization of bis(hydroperoxide) 249 with potassium tert-butoxide (Scheme 71) [252].

Scheme 71.

Inramolecular cyclization with MsO fragment substitution.

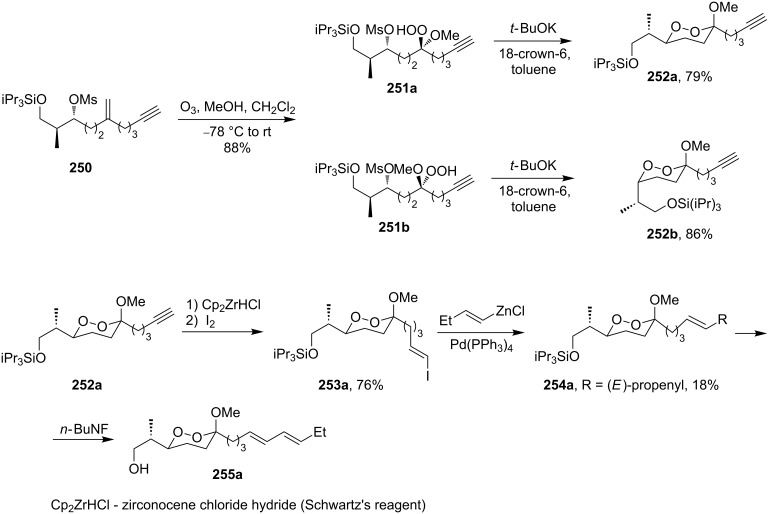

An approach to the cyclization based on an intramolecular nucleophilic substitution was used also for the synthesis of diastereomers of dioxanes 252a,b containing triple bonds. Hydroperoxides 251a,b that were synthesized by the ozonolysis of 250 were treated with potassium tert-butoxide. One of the diastereomers, 252a, was then modified first via the stereoselective hydrozirconation and iodination to 253a and then by the Negishi cross coupling to produce silylated product 254a, which was desilylated to obtain alcohol 255a (Scheme 72). 1,2-Dioxane 255a is structurally similar to natural peroxyplakoric acids having fungicidal and antimalarial activities [332].

Scheme 72.

Synthesis of 1,2-dioxane 255a, a structurally similar compound to natural peroxyplakoric acids.

3.8. Use of halonium ions in the cyclization

This approach to the synthesis of 1,2-dioxane rings is based on the intramolecular cyclization of hydroperoxides containing a C=C group. In the first step, the addition of a halonium ion to the double bond results in the formation of a carbocation, which is subjected to the intramolecular attack of the hydroperoxide group.

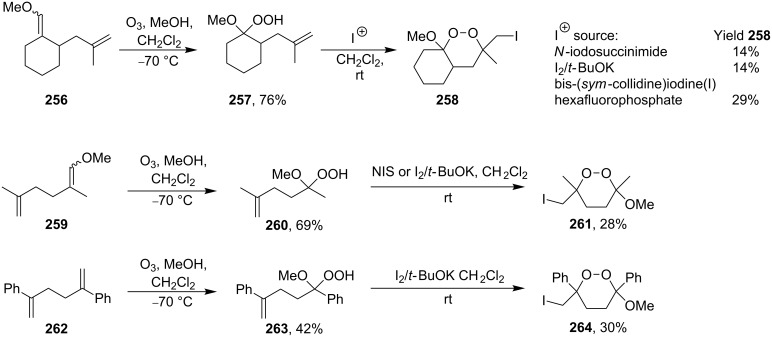

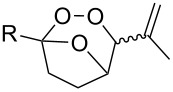

The treatment of unsaturated monoperoxyketals 257, 260, and 263 (prepared by ozonolysis of 256, 259, and 262 in methanol, respectively) with such donors of halonium ions such as N-iodosuccinimide (NIS), I2/t-BuOK, or bis(sym-collidine)iodonium hexafluorophosphate gave iodine-containing 1,2-dioxanes 258, 261, and 264, in moderated yields (Scheme 73) [333]. It should be noted that attempts to synthesize related peroxides with N-bromosuccinimide failed [333].

Scheme 73.

Synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes based on the intramolecular cyclization of hydroperoxides containing C=C groups.

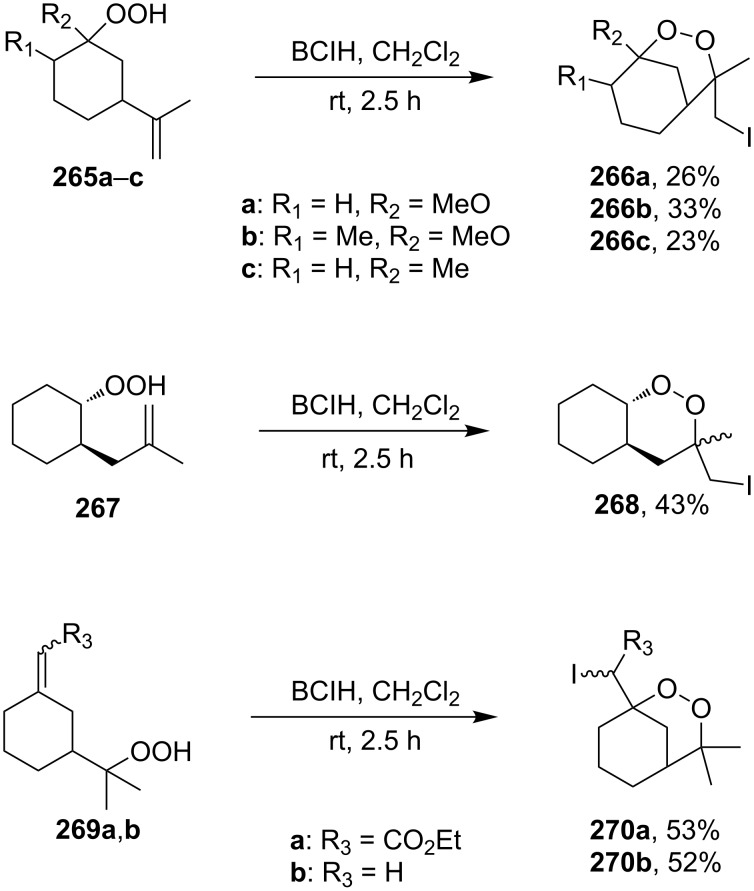

In the studies [334–335] iodine-containing 1,2-dioxanes 266a–c, 268, and 270a,b were synthesized from the corresponding hydroperoxyalkenes 265a–c, 267, and 269a,b with bis(sym-collidine)iodonium hexaflulorophosphate (BCIH) in the cyclization step (Scheme 74).

Scheme 74.

Use of BCIH in the intramolecular cyclization.

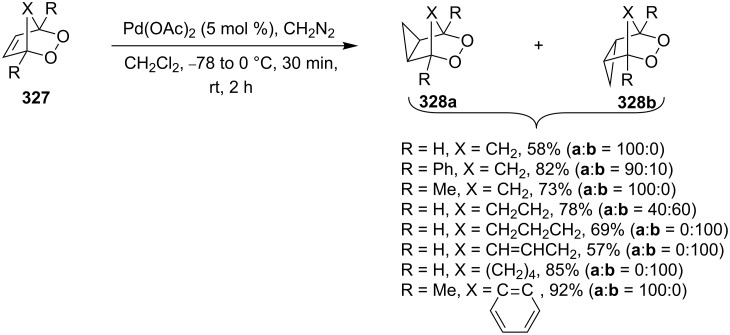

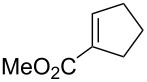

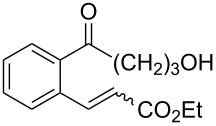

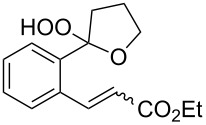

3.9. Pd(II)-catalyzed cyclization

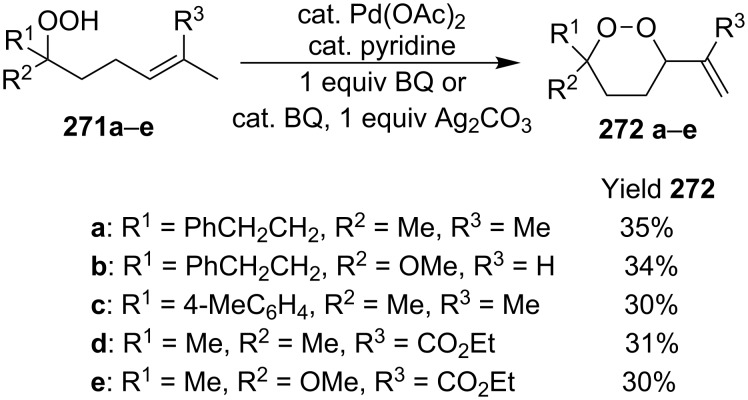

The palladium-catalyzed cyclization of δ-unsaturated hydroperoxides 271 represents a new route to 1,2-dioxane cyclic compounds 272 (Scheme 75). The cyclization was performed in toluene, 1,4-dioxane, or 1,2-dichloroethane at 80 °C for 3 h in the presence of p-benzoquinone or silver carbonate as the oxidizing agent for Pd(0) that was formed in the catalytic cycle. To the best of our knowledge, this method is the first example of a palladium acetate-catalyzed synthesis of cyclic peroxides [336].

Scheme 75.

Palladium-catalyzed cyclization of δ-unsaturated hydroperoxides 271a–e.

3.10. Acid-mediated cyclizations of peroxides

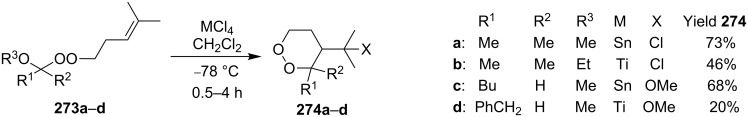

The intramolecular cyclization of unsaturated peroxyacetals 273a–d in the presence of TiCl4 or SnCl4 occurs via formation of peroxycarbenium ions to give methoxy- and chlorine-containing dioxanes 274a–d as the reaction products (Scheme 76) [257].

Scheme 76.

Intramolecular cyclization of unsaturated peroxyacetals 273a–d.

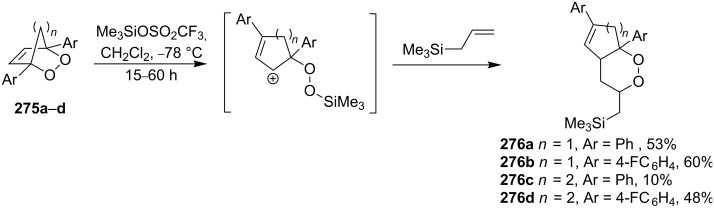

The treatment of endoperoxides 275a–d with allyltrimethylsilane in the presence of catalytic amounts of trimethylsilyl triflate or SnCl4 gave bicyclic 1,2-dioxanes 276a–d (Scheme 77) [337].

Scheme 77.

Allyltrimethylsilane in the synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes 276a–d.

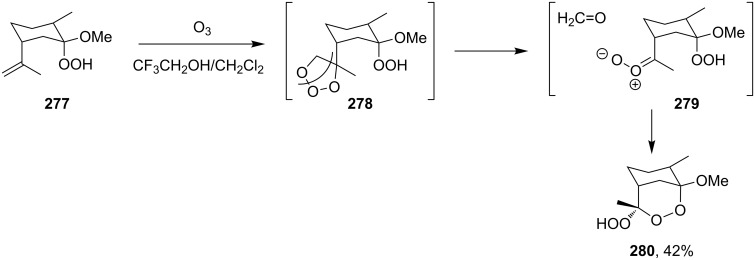

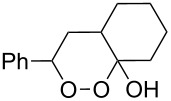

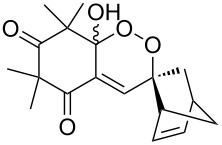

The electrophilic center of the peroxycarbenium ion produced by the decomposition of molozonide can be trapped by the hydroperoxide group of the molecule. This type of cyclization was used as the basis for the synthesis of hydroperoxide-containing 1,2-dioxanes. The ozonolysis of 1-hydroperoxy-1-methoxy-2-methyl-5-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohexane (277) in a trifluoroethanol/dichloromethane mixture through formation of molozonide 278 and peroxycarbenium ion 279 finally afforded (6S)-6-hydroperoxy-1-methoxy-2,6-dimethyl-7,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (280) (Scheme 78) [334]. The intramolecular cyclization of intermediate 279 is only possible if the hydroperoxide group is in a particular spatial arrangement [334].

Scheme 78.

Intramolecular cyclization using the electrophilic center of the peroxycarbenium ion 279.

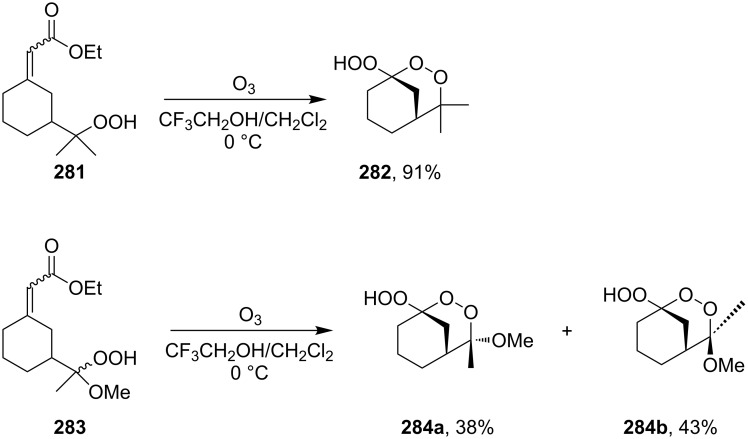

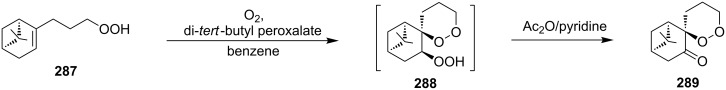

Under these conditions, ethyl 2-(3-(2-hydroperoxypropan-2-yl)cyclohexylidene)acetate hydroperoxide (281) and ethyl 2-(3-(1-hydroperoxy-1-methoxyethyl)cyclohexylidene)acetate hydroperoxide (283) react to form dioxanes, (1S,5S)-1-hydroperoxy-4,4-dimethyl-2,3-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (282), (1S,4S,5S)-1-hydroperoxy-4-methoxy-4-methyl-2,3-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (284a), and (1S,4R,5S)-1-hydroperoxy-4-methoxy-4-methyl-2,3-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (284b) (Scheme 79) [338].

Scheme 79.

Synthesis of bicyclic 1,2-dioxanes.

Under similar conditions, the reaction of 5-hydroperoxy-5-(2-methoxyethoxy)-2-methylhex-1-ene (285) in AcOH/CH2Cl2 produced 3-hydroperoxy-6-(2-methoxyethoxy)-3,6-dimethyl-1,2-dioxane (286) (Scheme 80) [270].

Scheme 80.

Preparation of 1,2-dioxane 286.

3.11. Other methods for the synthesis of 1,2-dioxanes

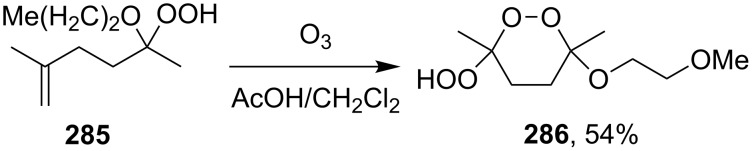

The di(tert-butyl)peroxalate-initiated radical cyclization of unsaturated 2-(3-hydroperoxypropyl)-6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene hydroperoxide (287) in the presence of oxygen gave 1,2-dioxane (289). The reaction proceeds through formation of compound 288 containing a hydroperoxide group, which is transformed into a carbonyl group by treatment with Ac2O/pyridine (Scheme 81) [232]. The yield of 289 was 14% based on 287.

Scheme 81.

Di(tert-butyl)peroxalate-initiated radical cyclization of unsaturated hydroperoxide 287.

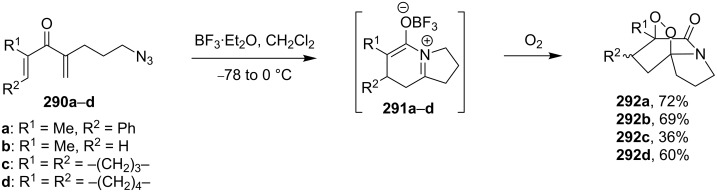

The original cyclization occurs during the oxidation of 1,4-betaines 291a–d prepared from dienones 290a–d containing an azide group in the side chain. The reaction yields peroxide-bridged indolizinediones 292a–d (Scheme 82) [339].

Scheme 82.

Oxidation of 1,4-betaines 291a–d.

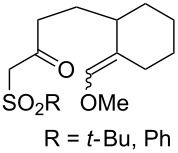

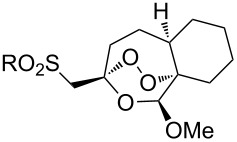

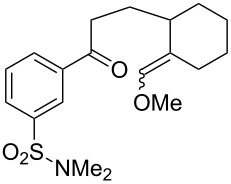

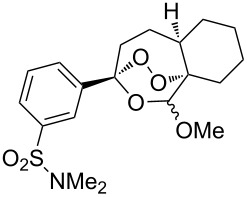

3.12. Structural modifications, in which 1,2-dioxane ring remains intact

This section deals with syntheses of compounds exhibiting high antimalarial activity that is comparable with or higher than that of artemisinin.

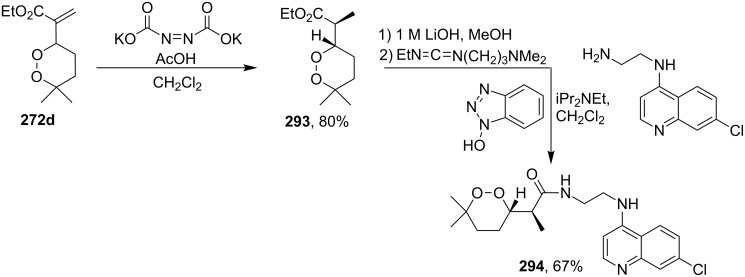

N-(2-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-ylamino)ethyl)-2-((S)-6,6-dimethyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)propanamide (294) containing the aminoquinoline moiety that is characteristic for antiparasitic compounds was synthesized by the following series of steps: reduction of the double bond in the presence of the peroxide group (transformation of ethyl 2-(6,6-dimethyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)acrylate (272d) into ethyl 2-((S)-6,6-dimethyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)propanoate (293)), alkaline hydrolysis, and amidation (Scheme 83) [336].

Scheme 83.

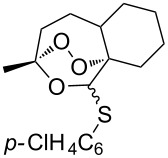

Synthesis of aminoquinoline-containing 1,2-dioxane 294.

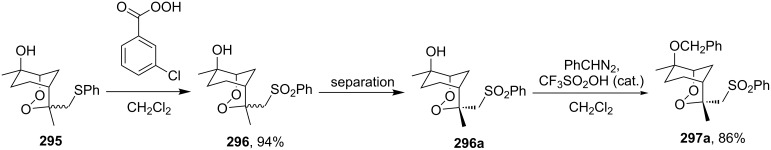

The synthesis of the sulfonyl-containing 1,2-dioxane 2-(benzyloxy)-2,6-dimethyl-6-(phenylsulfonylmethyl)-7,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane )297a), included the following steps: oxidation of the sulfide group in 2,6-dimethyl-6-(phenylthiomethyl)-7,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-ol (295) to form 2,6-dimethyl-6-(phenylsulfonylmethyl)-7,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-ol (296) followed by the isolation of the isomer (6R)-2,6-dimethyl-6-(phenylsulfonylmethyl)-7,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-ol (296a) and benzylation of the latter to obtain the target peroxide 297a (Scheme 84) [107].

Scheme 84.

Synthesis of the sulfonyl-containing 1,2-dioxane.

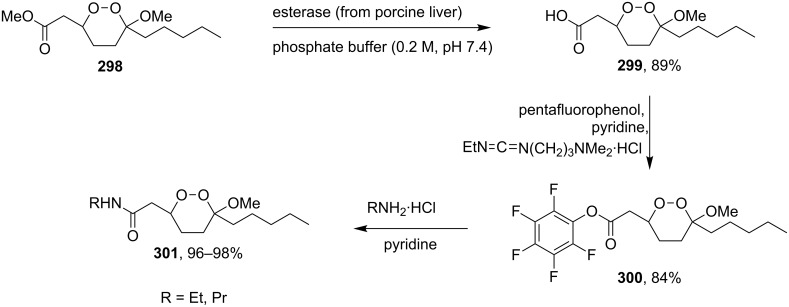

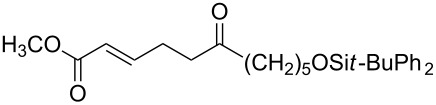

Methyl 2-(6-methoxy-6-pentyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)acetate (298) was enzymatically hydrolyzed to 2-(6-methoxy-6-pentyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)acetic acid (299). The next step in the synthesis of target compound 301 involved the two-step amidation via the intermediate formation of perfluorophenyl 2-(6-methoxy-6-pentyl-1,2-dioxan-3-yl)acetate (300) (Scheme 85) [110].

Scheme 85.

Synthesis of the amido-containing 1,2-dioxane 301.

The enzymatic hydrolysis step was necessary because attempts to hydrolize ester 298 under alkaline conditions (LiOH in dimethyl sulfoxide) failed and led to peroxide ring-opening [110].

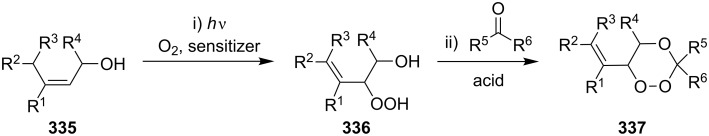

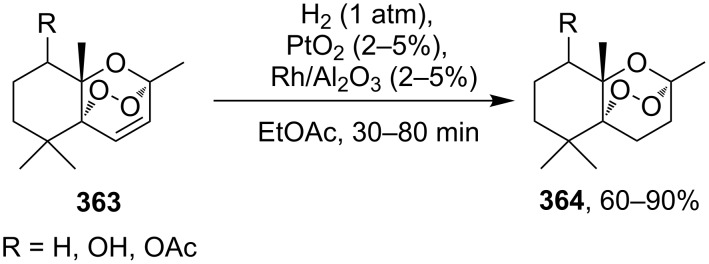

4. Synthesis of 1,2-dioxenes

4.1. Reaction of 1,3-dienes with singlet oxygen

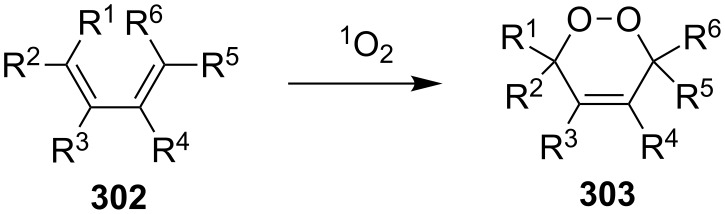

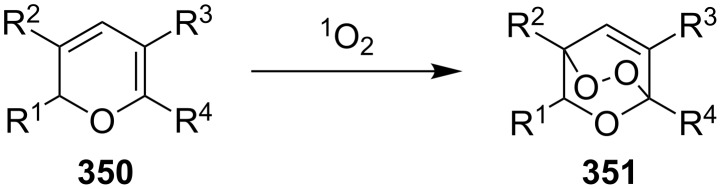

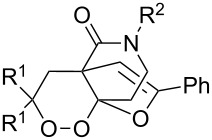

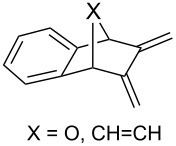

The reaction of singlet oxygen with the 1,3-diene system can proceed by the following pathways: the [4 + 2]-cycloaddition, the singlet-oxygen–ene reaction, and the [2 + 2]-cycloaddition to form dioxetanes. The reaction pathway depends on the nature of the solvent, and on electronic and steric factors. However, the [4 + 2]-cycloaddition (302 + 1O2) occurs in most cases, and this reaction is frequently used for the synthesis of the 1,2-dioxene system 303 (Scheme 86). Table 18 gives examples of 1,2-dioxenes synthesized by the reaction of singlet oxygen with 1,3-diene systems.

Scheme 86.

Reaction of singlet oxygen with the 1,3-diene system 302.

Table 18.

Examples of the use of 1O2 in the synthesis of 1,2-dioxenes.

| Alkene 302 | Reaction conditions | 1,2-Dioxene 303 | Yield, % | Reference |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 1 h |  |

100 | [340] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 2 h |  |

85 | [341] |

|

O2, hν, fullerene C60, CDCl3, 0 °C, 2 h |  |

93 | [342] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CCl4 |  |

75 | [343] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CCl4, rt, 30 min |  |

90 | [344] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CCl4, rt, 18–20 h |  |

74 95 |

[345] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CCl4, 10 °C, 1.5 h |  |

73 | [346] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CHCl3, 10 °C, 45 min |  |

94 | [346] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CCl4, rt, 24 h to 9 d |  |

94 36 |

[347] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CH2Cl2, −10 °C, 6 h |  |

54 | [348] |

|

1) O2, hν, Rose Bengal, MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1/19), 0 °C, 8 h 2) CH2N2 |

|

40 | [182–183] |

|

1) O2, hν, methylene blue, CH2Cl2, 15 °C, 30 min 2) PPh3, acetone, rt, 40 min |

|

50 | [349] |

|

O2, hν, Rose Bengal, MeCN, 0 °C, 6–16 h |  |

54–82 | [350] |

|

O2, hν, Rose Bengal, MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1/19), 0 °C, 6 h |  |

42 66 |

[351] |

|

O2, hν, Rose Bengal, CH2Cl2, 6 h |  |

23–70 | [352] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, benzene, 18 h |  |

28 | [353] |

|

O2, hν, Rose Bengal, EtOH, 10 °C, 70 min |  |

56 | [186–190] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CH2Cl2 |  |

13–95 | [191–195] |

|

O2, hν, Rose Bengal, CH2Cl2 |  |

89 | [354] |

|

O2, hν, tetraphenylporphyrin, CHCl3 or Rose Bengal, MeOH, −15 to 0 °C, 1–4 h |  |

70–92 | [355] |

|

O2, hν, Rose Bengal, CH2Cl2, 6 h |  |

91 | [356] |

|

air, sunlight, CHCl3, rt, 5 d or O2, hν, CH2Cl2, CuSO4, TsOH, 1 h |  |

53–80 | [357–358] |

|

air, sunlight, CHCl3, rt, 3 d |  |

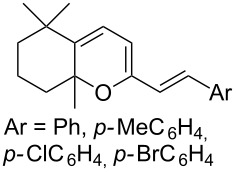

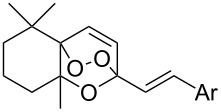

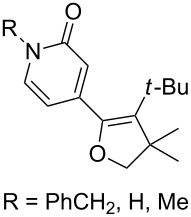

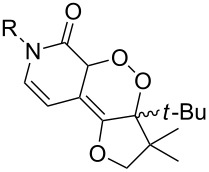

60–85 | [113–116] [359–360] |

|

air, sunlight, CHCl3, rt, 3 d |  |

23 | [119] |

|

air, sunlight, CHCl3, rt, 6 d |  |

15 | [119] |

|

air, sunlight, CCl4, rt, 160 h |  |

55–80 | [361] |

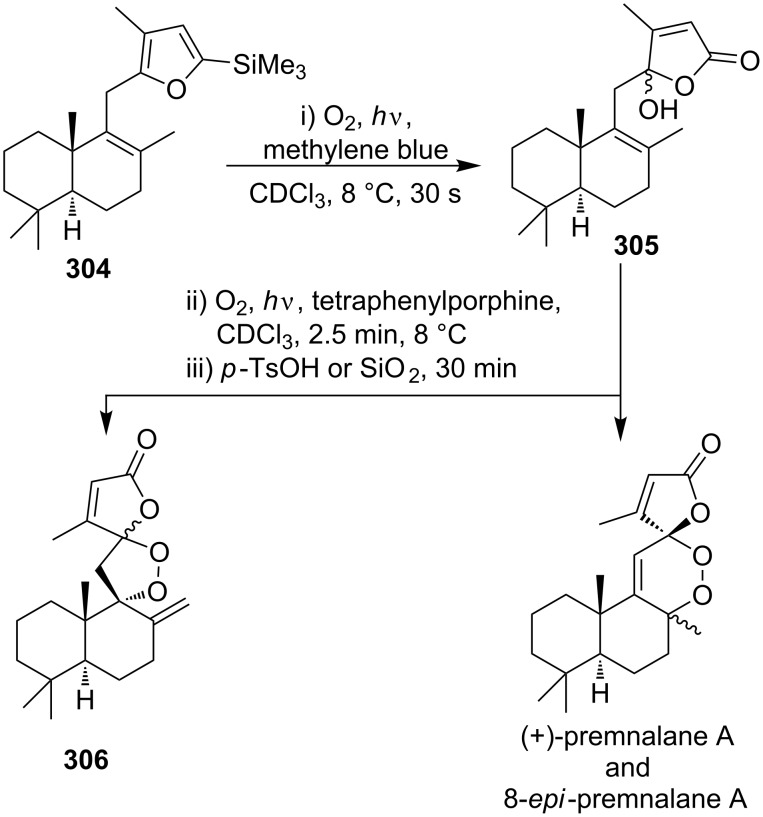

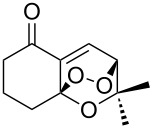

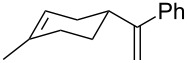

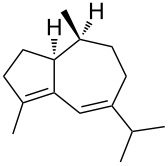

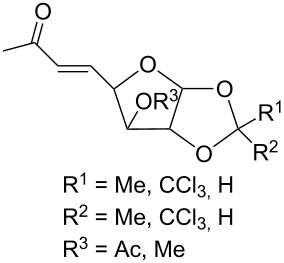

(+)-Premnalane A is a natural compound of plant origin exhibiting pronounced antimicrobial activity. The synthesis of this compound includes the following steps: oxidation of the furan ring of compound 304, the singlet-oxygen–ene reaction of the double bond-containing bicyclic compound 305, and acid-induced ketalization (Scheme 87) [362].

Scheme 87.

Synthesis of (+)-premnalane А and 8-epi-premnalane A.

This synthesis produced a 1:1 mixture of diastereomeric (+)-premnalane А and 8-epi-premnalane A in 24% combined yield and diastereomeric 1,2-dioxolanes 306 in 49% yield. Pure (+)-premnalane A was isolated by column chromatography.

4.2. Structural modifications, in which 1,2-dioxene ring remains intact

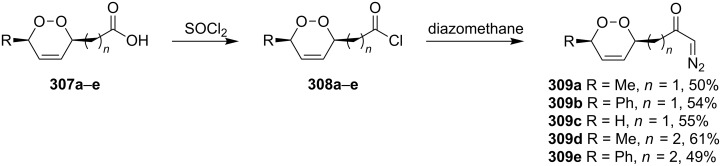

Diazo-containing 1,2-dioxenes 309a–e were synthesized starting from the corresponding acids 307a–e, which were transformed into acid chlorides 308a–e and then subjected to diazotization (Scheme 88) [363]. The 1,2-dioxenes 309a–e were used for the intramolecular insertion of carbenes, that were produced by decomposition of the diazo group, into the –О–О–bond [363].

Scheme 88.

Synthesis of the diazo group containing 1,2-dioxenes 309a–e.

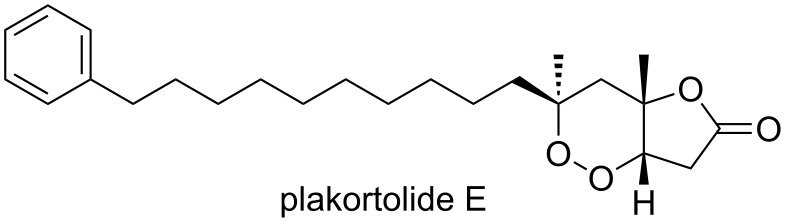

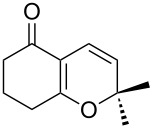

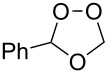

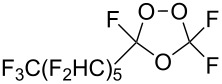

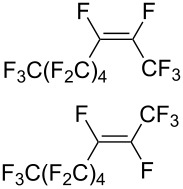

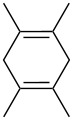

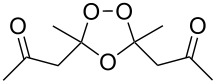

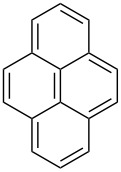

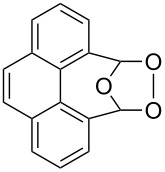

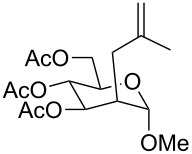

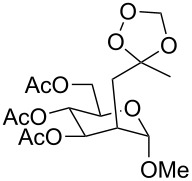

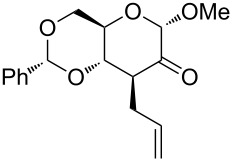

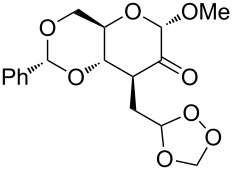

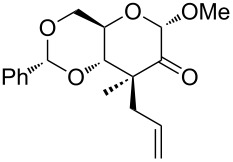

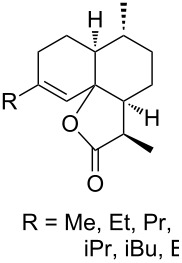

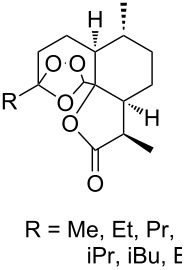

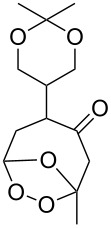

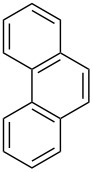

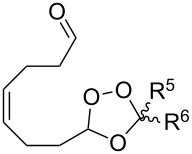

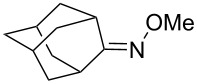

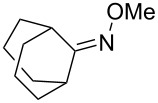

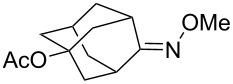

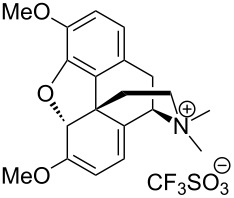

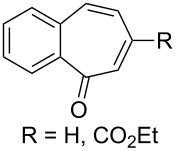

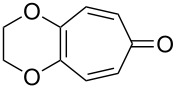

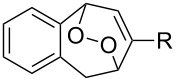

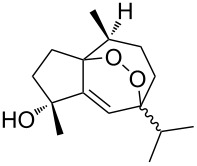

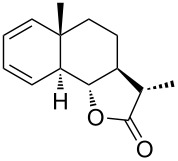

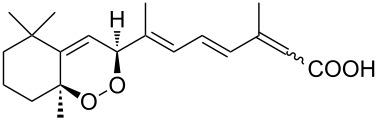

6-Epiplakortolide Е is a bicyclic peroxylactone that was isolated in low yield (0.0003%) from the marine sponge Plakortis sp. The structurally related plakortolide Е (Figure 4) exhibits high cytotoxicity against cancer cells and shows also activity against Toxoplasma gondii, which is the causative agent of toxoplasmosis [184–185].

Figure 4.

Plakortolide Е.

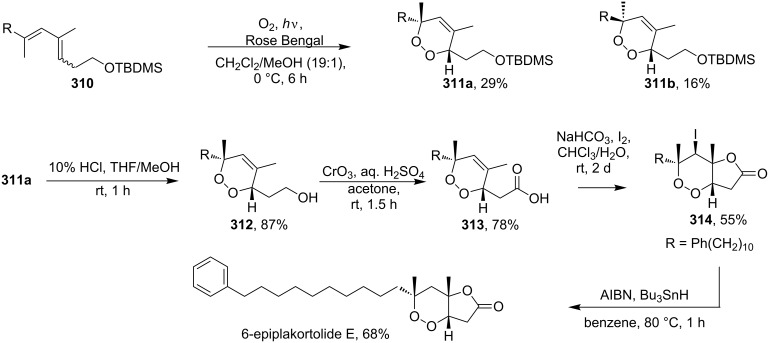

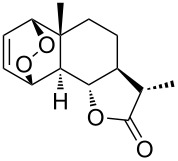

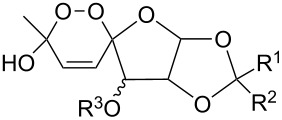

6-Epiplakortolide Е was synthesized by the multistep synthesis involving the oxidation of diene 310 with singlet oxygen to give two isomeric 1,2-dioxenes 311a,b, the isolation of dioxene 311a, its silyl deprotection to form alcohol 312, the oxidation of the latter to 1,2-dioxenic acid 313, the I+-induced lactonization to produce 314, and the deiodination to obtain the target product (Scheme 89) [184–185]. It should be noted that the cyclic peroxide compound 314 remains intact under the reductive conditions in the presence of tributylstannane; this step occurs in good yield (68%) [184–185].

Scheme 89.

Synthesis of 6-epiplakortolide Е.

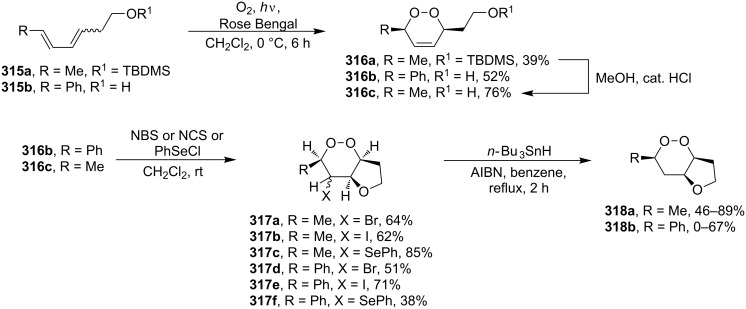

More recently, a similar approach was used for the preparation of tetrahydrofuran-containing bicyclic peroxides 318a,b. It involves the synthesis of 1,2-dioxenes 316 from dienes 315, the cation-initiated cyclization to give bicyclic compounds 317, and the reduction with Bu3SnH. N-Bromo- and iodosuccinimides (NBS and NIS, respectively) were used as donors of halogenide ions. Additionallay, the cyclization was successfully performed with the use of phenylselenyl chloride as the donor of PhSe+ cation (Scheme 90) [364].

Scheme 90.

Application of Bu3SnH for the preparation of tetrahydrofuran-containing bicyclic peroxides 318a,b.

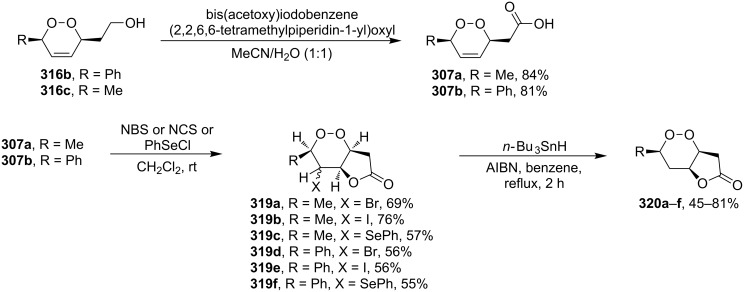

Acids 307a and 307b were synthesized by oxidation of the corresponding alcohols with the bis(acetoxy)iodobenzene/2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyl oxyl (BAIB/TEMPO) system. The cyclization to bicyclic peroxides 319a–f containing the lactone ring was performed with the use of N-bromo- and iodosuccinimides and PhSeCl (Scheme 91) [364]. As in the above-considered case, the peroxide ring remains unchanged upon the reduction of the С–X bond in compounds 319a–f with Bu3SnH [364].

Scheme 91.

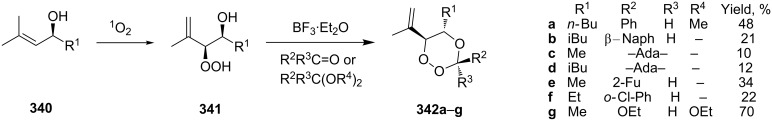

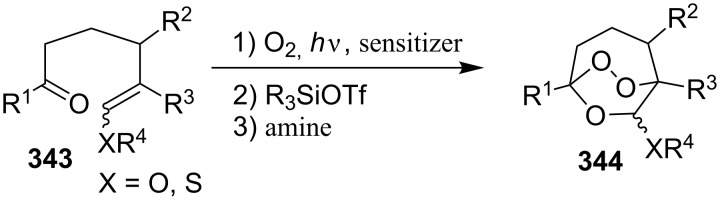

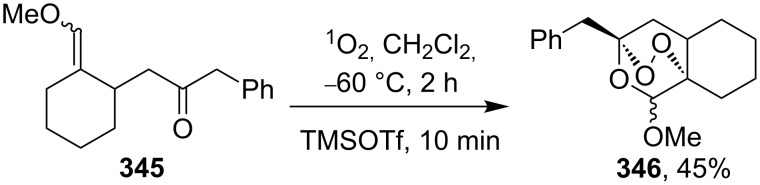

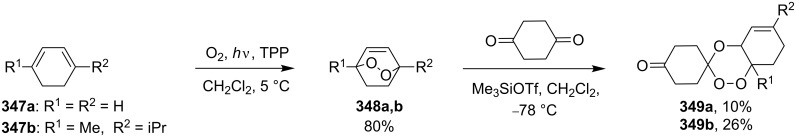

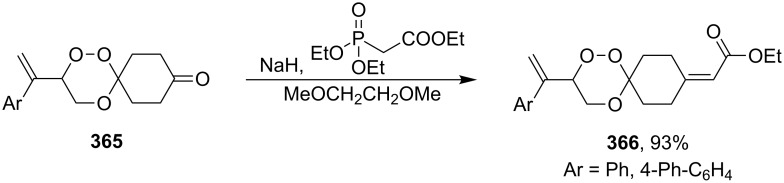

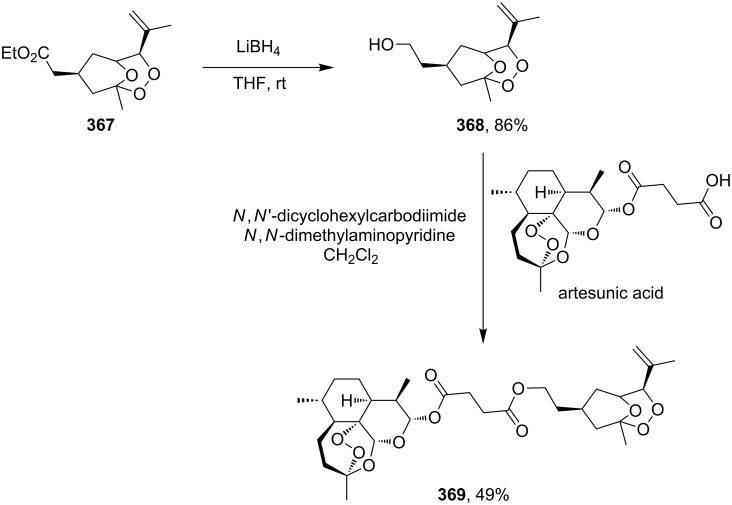

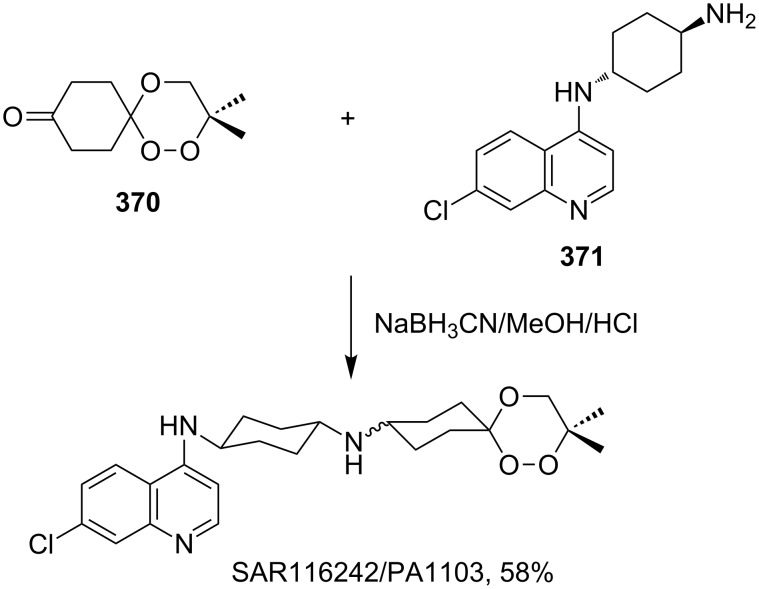

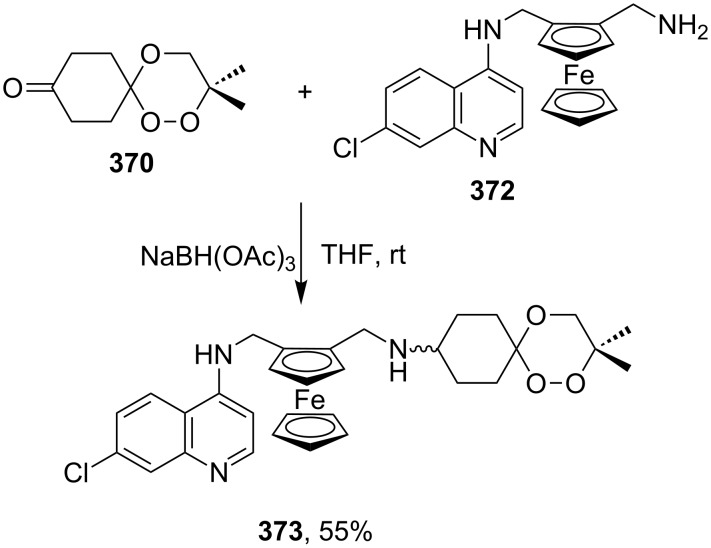

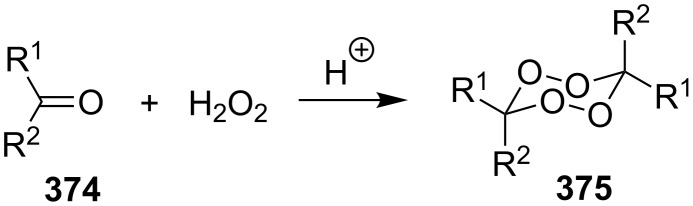

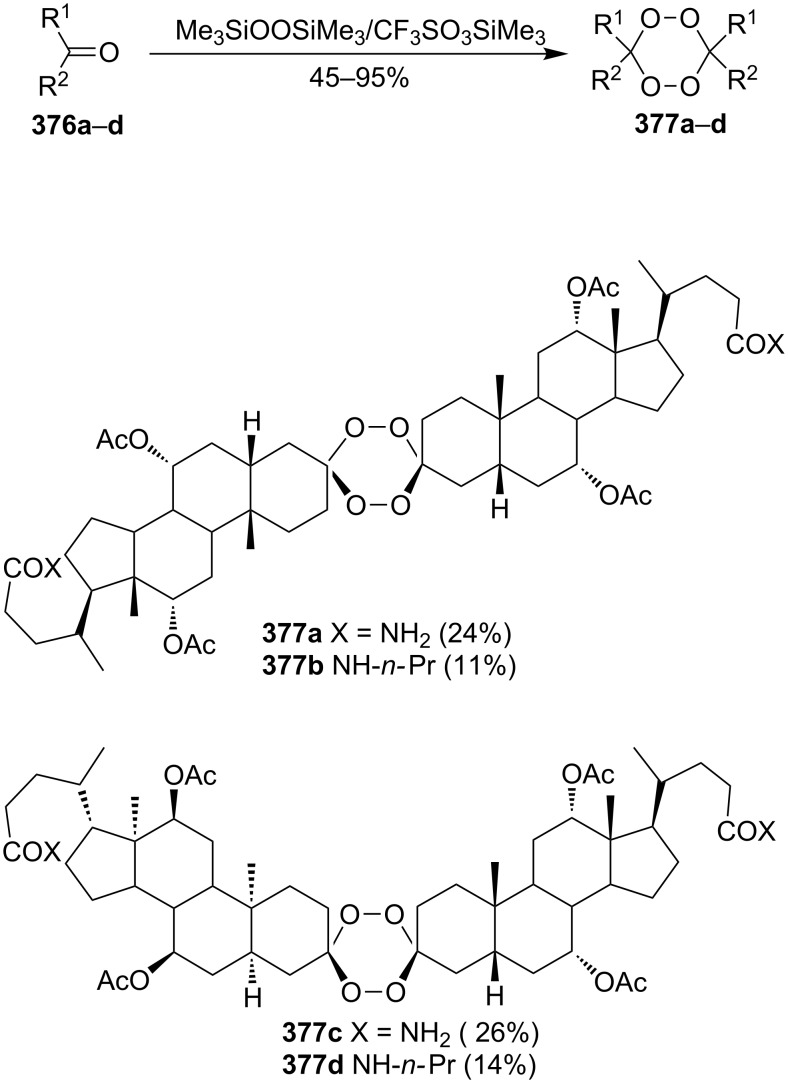

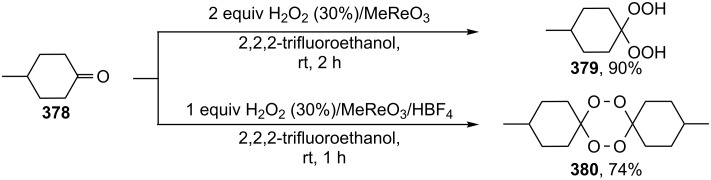

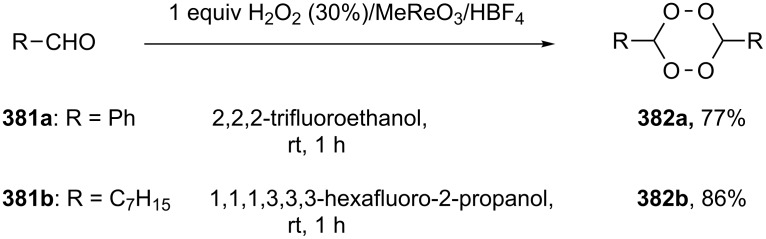

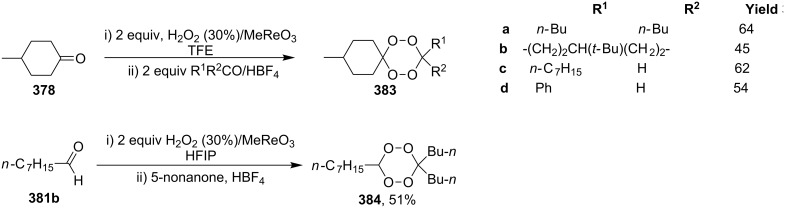

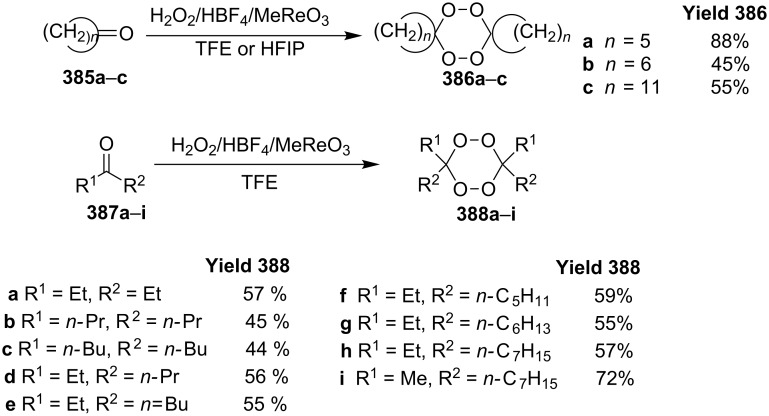

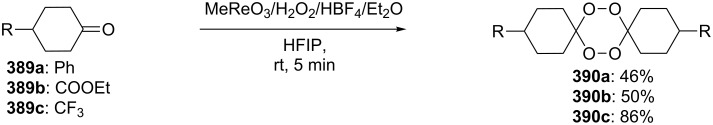

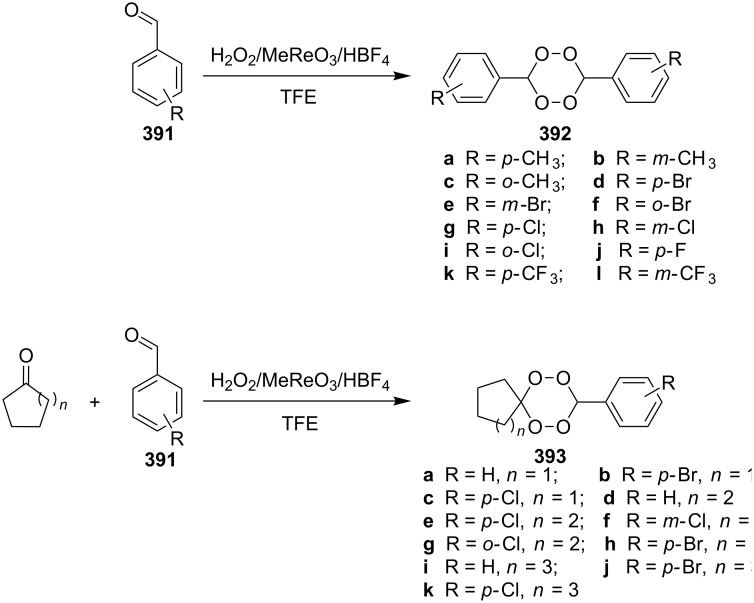

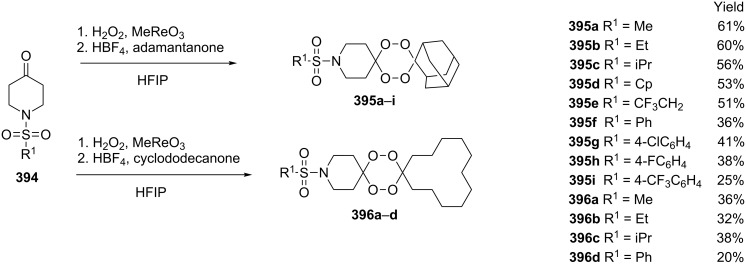

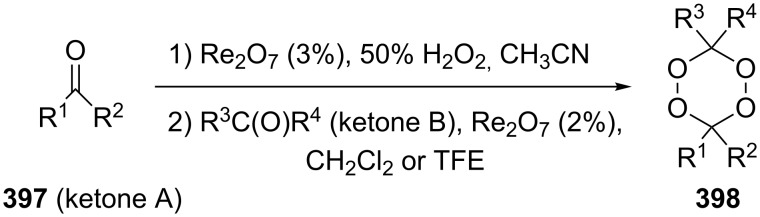

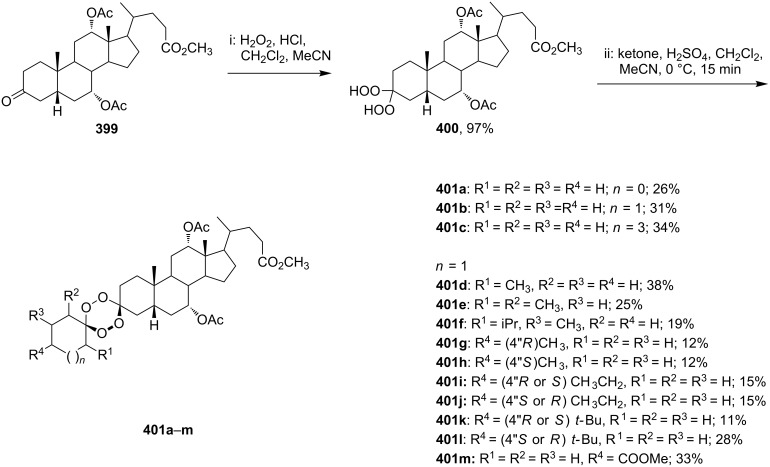

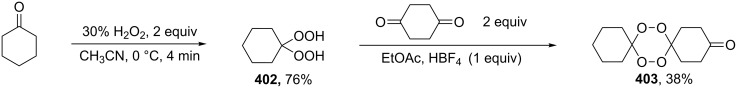

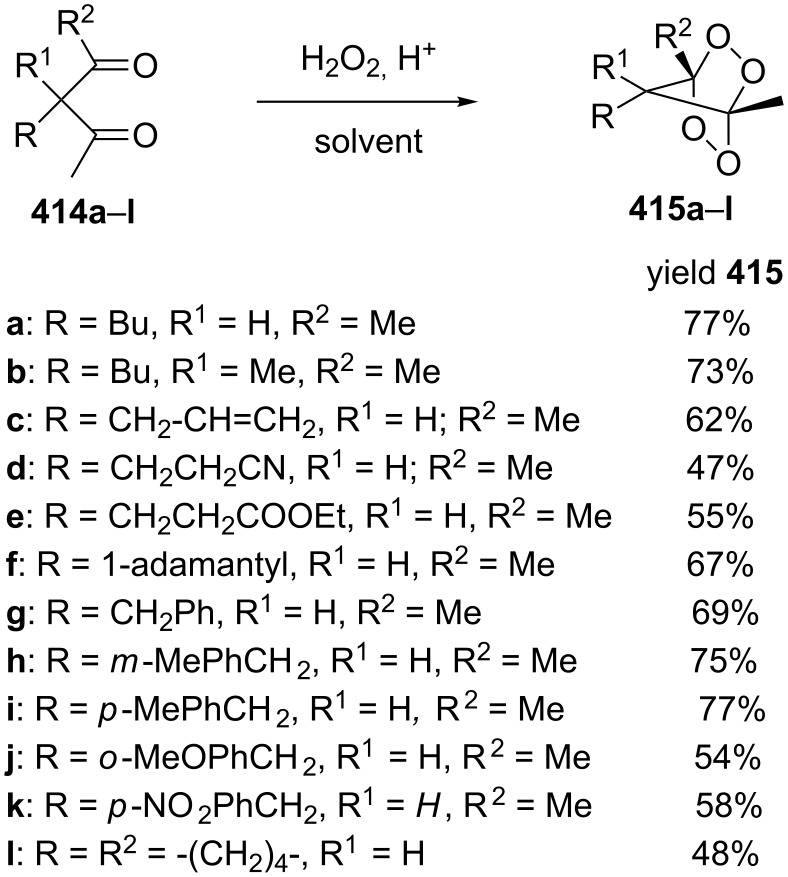

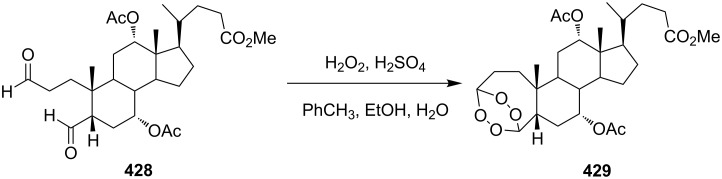

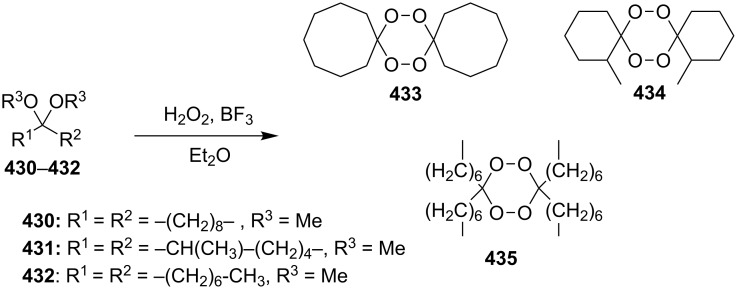

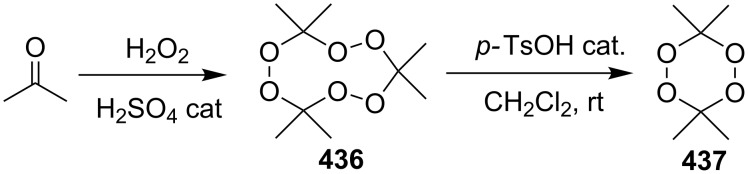

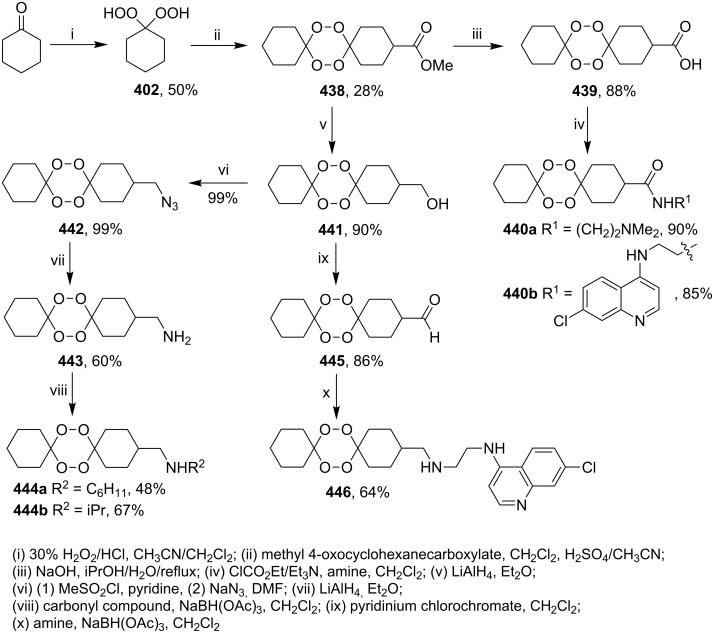

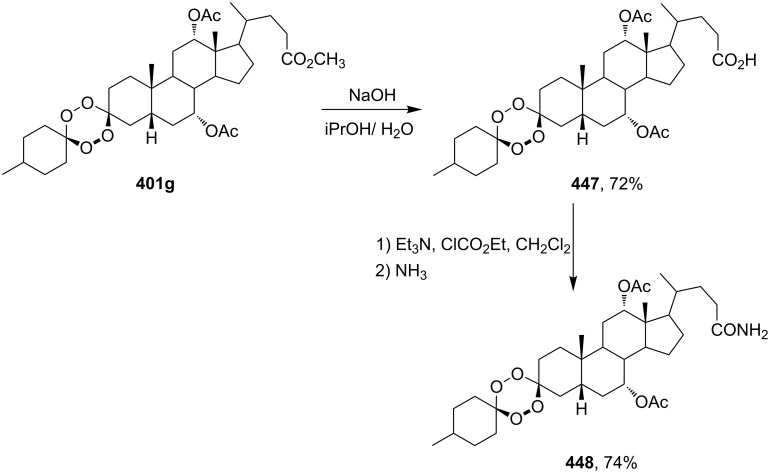

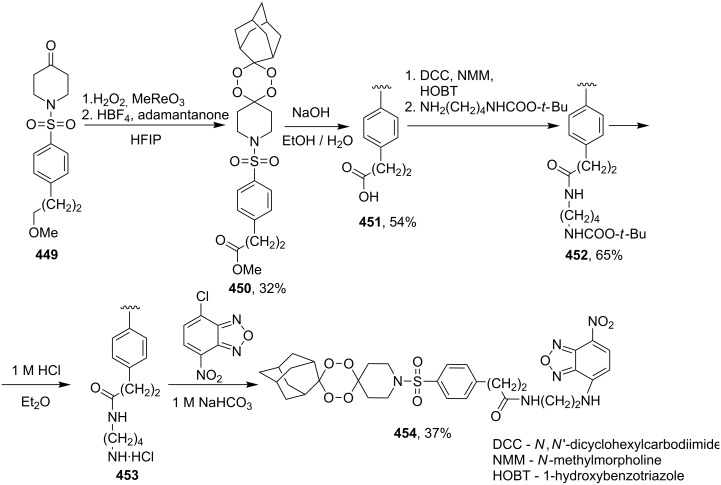

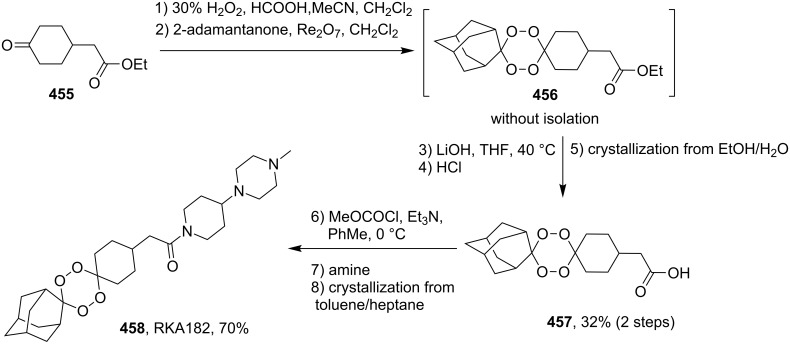

Application of Bu3SnH for the preparation of lactone-containing bicyclic peroxides 320a–f.