Abstract

Within the Drosophila embryo, two related bHLH-PAS proteins, Single-minded and Trachealess, control development of the central nervous system midline and the trachea, respectively. These two proteins are bHLH-PAS transcription factors and independently form heterodimers with another bHLH-PAS protein, Tango. During early embryogenesis, expression of Single-minded is restricted to the midline and Trachealess to the trachea and salivary glands, whereas Tango is ubiquitously expressed. Both Single-minded/Tango and Trachealess/Tango heterodimers bind to the same DNA sequence, called the CNS midline element (CME) within cis-regulatory sequences of downstream target genes. While Single-minded/Tango and Trachealess/Tango activate some of the same genes in their respective tissues during embryogenesis, they also activate a number of different genes restricted to only certain tissues. The goal of this research is to understand how these two related heterodimers bind different enhancers to activate different genes, thereby regulating the development of functionally diverse tissues. Existing data indicates that Single-minded and Trachealess may bind to different co-factors restricted to various tissues, causing them to interact with the CME only within certain sequence contexts. This would lead to the activation of different target genes in different cell types. To understand how the context surrounding the CME is recognized by different bHLH-PAS heterodimers and their co-factors, we identified and analyzed novel enhancers that drive midline and/or tracheal expression and compared them to previously characterized enhancers. In addition, we tested expression of synthetic reporter genes containing the CME flanked by different sequences. Taken together, these experiments identify elements overrepresented within midline and tracheal enhancers and suggest that sequences immediately surrounding a CME help dictate whether a gene is expressed in the midline or trachea.

Introduction

The genes expressed within a particular cell type control its developmental fate and physiological potential. Early in development, master control genes play pivotal roles in controlling cell fate and most master control genes are transcription factors that promote their own expression as well as a variety of downstream target genes. Each target gene, in turn, contributes to tissue development by regulating cellular processes, such as 1) morphology 2) interactions with surrounding cells through signaling, 3) cell divisions and/or 4) the expression of additional genes. To understand how genes are differentially regulated within tissues, we compare the development and gene expression of two tissues in the Drosophila embryo: the central nervous system (CNS) midline and the trachea. In Drosophila, Single-minded (Sim) is the master control gene of CNS midline cells [1]–[3], while Trachealess (Trh) plays a large role in the development of the fly’s respiratory system, the trachea [4]–[6]. Both Sim and Trh are bHLH-PAS proteins and independently heterodimerize with a common partner, Tango (Tgo), before binding to DNA and activating transcription [7], [8]. Tgo is also a bHLH-PAS protein and paradoxically, Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo both bind to a shared five base pair recognition sequence, ACGTG, called the CNS midline enhancer element (CME). Tgo is ubiquitously expressed, whereas Sim is restricted to the midline [9] and Trh to the trachea and a few other tissues, including the salivary gland, filzkorper and CNS [4], [5]. In most cells, Tgo is located in the cytoplasm, but within cells that express one of its partner proteins, such as Sim or Trh, Tgo is transported to the nucleus and upregulated [10]. Once in the nucleus, Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo activate overlapping and distinct gene sets [7], [8], [11]–[13].

Single-minded and the Midline

The embryonic midline and trachea differ in many ways and the following is a brief summary and comparison of the development of these tissues during Drosophila embryogenesis. CNS midline cells are specified early in embryogenesis when sim is activated prior to gastrulation, in a single row of cells sandwiched in between the mesoderm and ectoderm on each side of the embryo; cells called the mesectoderm [9]. Sim protein is first expressed during gastrulation as the two rows of mesectodermal cells come together at the ventral midline. After meeting ventrally, midline cells invaginate to form a signaling center that organizes the CNS as it matures symmetrically on either side of the midline. As CNS axons differentiate, midline glia secrete Netrin (Net) A and B to attract axons to cross the midline [14]–[16] and then slit to prevent recrossing [17]–[19]. Some axons continually express roundabout (robo), the receptor for slit [18], at the growth cone surface and never cross the midline, whereas axons that cross the midline require commissureless (comm) to temporarily prevent robo localization at the growth cone, allowing them to cross [20]–[23]. During mid to late embryogenesis, midline cells differentiate into glia and six neural subtypes that can be distinguished based on their gene expression patterns (Fig. 1A–B) [11], [24]. By the time the embryo hatches into a larva, most midline neurons have differentiated and begun to secrete subtype specific neurotransmitters and make connections with target tissues [24], [25]. In addition, the midline glia have enwrapped and secured the CNS axons that cross the midline [1], [26].

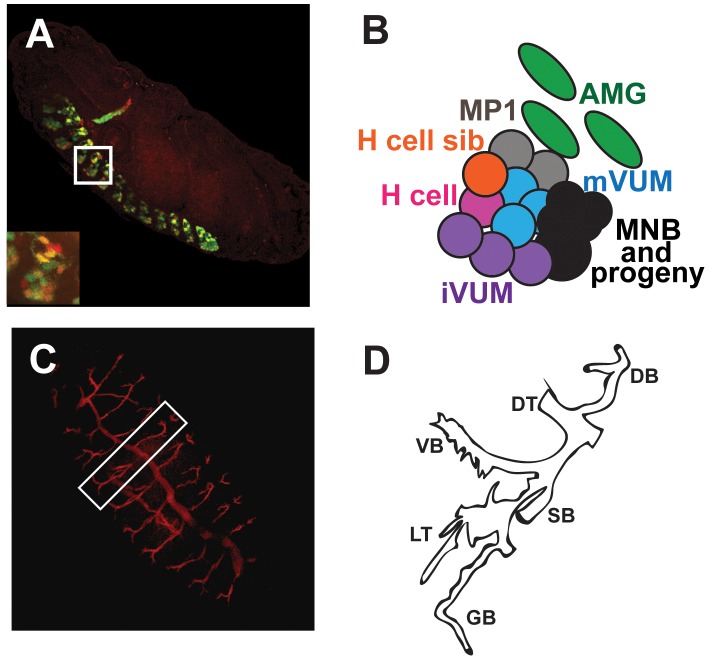

Figure 1. Relative locations of the CNS midline and trachea within the late Drosophila embyo.

(A) The midline cellular pattern is segmentally repeated throughout the ventral nerve cord at embryonic stage 16. (B) Each segment consists of six neural subtypes and three surviving midline glia whose relative locations within a typical thoracic segment (white box and inset in A) are shown. The midline subtypes include: the MP1 neurons (gray), the H cell (pink), the H cell sib (orange), the ventral unpaired interneurons (iVUMs; purple), the ventral unpaired motorneurons (mVUMs; blue), median neuroblast (MNB) and its progeny (black) and the anterior midline glia (AMG; green); adapted from [24], [108]. (C) By the end of embryogenesis, the trachea form an extensive network that mediates gas exchange throughout the organism. (D) Each tracheal metamere consists of the major dorsal trunk (DT), a dorsal branch (DB), and the visceral (VB), spiracular (SB) and ganglionic (GB) branches and lateral trunk (LT) on the ventral side; adapted from [71]. Lateral views of whole mount embryos stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-sim (red; A) antibodies or monoclonal antibody 2A12 (red; C) and analyzed by confocal microscopy are shown. (A) The embryo contains a reporter gene that expresses GFP in all midline cells.

Trachealess and the Trachea

In Drosophila, the trachea are a network of air-filled tubes constructed during embryogenesis that function in gas exchange (reviewed in [27]–[30]). Tracheal cells can first be recognized during Drosophila gastrulation when ventral veinless (Vvl) and trh are activated by JAK/STAT signaling [31]–[34] within segmentally repeated tracheal pits or placodes [5], [35]. Decapentaplegic (Dpp) and Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) signaling limit the embryonic dorsal and ventral boundaries of the trachea, while wingless (wg) restricts the location of trachea within each segment [4], [5], [36]. As development progresses, terminal cells at the end of the growing tracheal tubes lead migration into tissues and specialized cells fuse to connect the separate, developing metameric trachea, creating a continuous tubular network. Fusion of lateral and dorsal trunks is facilitated by the Dysfusion (Dys) bHLH-PAS protein, another partner of Tgo [37]–[40] and after fusion, the two major tracheal tubes, called dorsal trunks, span the length of the embryo (Fig. 1C and D). Interestingly, insect trachea share functional and developmental similarities with the vertebrate vasculature. Both are interconnecting and branched tubular networks, function in gas exchange, and are patterned by related developmental genes and mechanisms [41]. For instance, signaling by fibroblast growth factor (FGF), called breathless (btl) in flies [42], [43], plays a key role in the formation of both of these tissues. Btl is expressed in all tracheal cells and leading cells of nascent branches interact with neighboring tissues through their production of the FGF signal, branchless, which stimulates and guides branch formation [44]. FGF signaling, together with the Drosophila hypoxia inducible factor, also guides later growth and branching of the trachea, driven, in part, by oxygen demands of tissues [41]. At the end of embryogenesis, the tracheal network fills with air and for the remainder of the fly’s life, the trachea delivers oxygen to its tissues.

Common and Distinct Genes and their Regulation within the Midline and Trachea

The functions and morphology of midline and tracheal cells differ, yet certain aspects of their embryonic development are similar. Both cell types are derived from the ectoderm (the midline is derived from the more specialized mesectoderm) and project long cellular extensions to form specialized contacts with many different cell types [45]–[48]. Moreover, midline glia and tracheal cells provide vital nutrients, growth factors and oxygen for active neurons within the mature embryo and larvae [6], [26]. While Sim is restricted to the midline and Trh to tracheal cells within the embryo, many genes are expressed in both the midline and trachea, including the Vvl POU domain transcription factor, which is needed to activate genes in both tissues [49], [50]. In addition, many signaling pathways, including Notch, FGF, EGF, engrailed, wg and hedgehog (hh) [11], [12], [26], [47], [51], [52] provide positional cues to regulate development of various cell types within both tissues. Downstream components of these signaling pathways combine with Sim and Trh in unique ways to regulate different gene sets in the midline and tracheal cells. Differences between the two tissues are likely due to the presence of additional, unknown tissue specific proteins that combine with Sim and Trh in unique ways to control gene expression and alter cell activity. In support of this idea, exchanging the PAS domains between Sim and Trh indicates these domains determine target gene specificity, presumably by binding to co-factors restricted to either the midline or trachea [13]. This is consistent with the known properties of PAS domains, which bind many different molecules and co-factors to respond to the environment [53]–[55]. Such co-factors may cause the Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo heterodimers to recognize slightly different DNA binding sites within enhancer regions of target genes. The goal of these experiments is to understand how Sim and Trh bind the same protein partner and DNA sequence, yet activate different gene sets in midline and tracheal cells.

To compare regulatory functions of Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo during fly development, we selected genes expressed in the midline, trachea or both tissues, identified enhancers that control the expression of each gene and compared them to previously identified midline and tracheal enhancers. To test the importance of previously identified sequence motifs, we generated synthetic reporters that contain the CME combined with binding sites for other factors expressed in the midline or trachea. To further analyze these enhancer sets, we searched for novel motifs common to both, as well as motifs unique to either midline or tracheal genes. The results identify sequence contexts, both proximal and distal to the CME, which promote midline and/or tracheal expression.

Materials and Methods

Production of Midline and Tracheal Reporter Genes and Transgenic Strains

Drosophila melanogaster genomic sequences encompassing select genes expressed in the midline and trachea were compared across the 12 sequenced Drosophila genomes [56] using the USCS genome browser (genome.ucsc.edu). The sequences examined included all introns within a gene and the intergenic regions located between the midline gene and its neighboring upstream and downstream gene. Identified regions conserved in at least 11 of the 12 genomes were first amplified within fragments ranging from ∼200–3500 bp using the primers listed in Table S1 and genomic DNA isolated from the yw67 Drosophila melanogaster strain. These fragments were either cloned into the pSTBlue1 intermediary vector and then into the pHstinger vector [57] using XhoI/KpnI digestion, or cloned into pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen) and transferred into pMintgate using the Gateway system [58]. Minor changes to this cloning scheme are noted below. Transgenic fly lines were generated with the pHstinger constructs using standard procedures and three independent lines analyzed for each GFP reporter gene. pMintgate constructs were injected into the φC31 genomic destination site attP2 (68A1-B2) as previously described [58].

CG33275. The CG33275 ML577 fragment was generated by first digesting the CG33275 ML 2544:GFP construct in pSTBlue with BglII, re-ligating it and then subcloning the remaining 577 bp fragment into pHstinger. The CG33275 ML 1312 fragment was generated from the CG33275 ML2544:GFP construct using KpnI/SwaI digestion and blunt end ligation, which removed 1232 bp from the original 2544 bp construct (Fig. 2B). The remaining 1312 bp fragment was then subcloned into pHstinger.

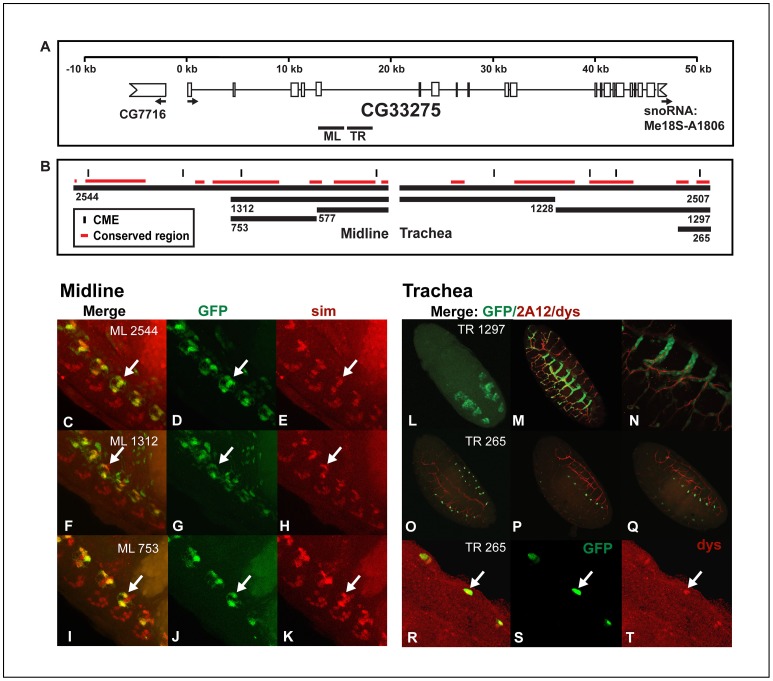

Figure 2. CG33275 contains a midline enhancer that is separable and distinct from a nearby tracheal enhancer.

(A) Locations of regions within the fifth intron of CG33275 used to generate the reporter constructs are shown. A scale is indicated on top and the thick lines represent the regions analyzed in (B–T). White boxes represent exons and thin lines represent introns. The indented boxes indicate flanking genes, CG7716 and snoRNA, and arrows indicate the start and direction of transcription. (B) Fragments used to generate reporter constructs are shown. The size of each fragment is indicated below it, vertical lines indicate locations of CMEs and red lines represent sequence blocks conserved in at least 11 Drosophila species. (C–T) Whole mount embryos were double-stained with anti-GFP (green: D, G, J, L and S), anti-sim (red; E, H, K), anti-dys (red; T) antibodies and monoclonal antibody 2A12 (red; M–Q) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression is shown in yellow in the merge images (C, F, I, M–Q and R). Reporters (C–E) CG33275 ML2544:GFP, (F–H) CG33275 ML1312:GFP and (I–K) CG33275 ML753:GFP drove expression in midline glia. Midline glia can be identified by the overlap in expression of GFP and sim (arrows C–K) and are located on the dorsal side of the nerve chord. Midline neurons are located on the ventral side of the nerve chord and labeled by sim, but do not express CG33275 or any of the CG33275 reporter genes. (L–T) Monoclonal antibody 2A12 labels the tracheal lumen and the anti-dys antibody labels tracheal fusion cells. CG33275 TR1297:GFP is expressed in all trachea, beginning in the tracheal pits at stage 12 (L) and extending to late embryogenesis (M–N), while CG33275 TR265:GFP is expressed only in fusion cells (O–T), indicated by co-localization of GFP and Dys (arrows R–T). Lateral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is on the left, except (L), which is a dorsal view of a stage 12 embryo.

liprin γ. The liprin γ 1781 fragment was generated from the liprin γ 3141:GFP construct using SacII/BamHI digestion, as previously reported [59].

Production of Synthetic Reporter Genes

To generate synthetic reporters, the forward and reverse primer pairs listed in Table S2 were phosphorylated, annealed, ligated and multimers consisting of four copies were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels, excised and purified with isobutanol extraction. The multimers were first cloned into EcoRI-digested Bluescript KS− and subsequently into pHstinger using KpnI/BamHI digestion. Each reporter gene was introduced into the Drosophila genome using P element mediated transformation and the GFP expression pattern of at least three transgenic lines examined.

Immunohistochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

Embryos were collected and labeled with antibodies as previously described [60]. The following antibodies were used to localize proteins in Drosophila embryos: rat anti-sim (1∶100) [10], rabbit anti-GFP (1∶500; Molecular Probes, Life Technologies), mouse anti-GFP (1∶200; Promega), rabbit anti-dys (1∶400) [39]; rabbit anti-odd-skipped (odd; 1∶400; Jim Skeath, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA); and anti-reversed polarity (repo; 1∶30), anti-engrailed (1∶1), and 2A12 (1∶5) MAbs (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Secondary antibodies were used at 1∶200 and included anti-rat-Alexa568, anti-mouse-Alexa568, anti-rabbit-Alexa405 and anti-rabbit-Alexa488 (Molecular Probes). Images were obtained on a Zeiss 710 in the Cellular and Molecular Imaging Facility at NCSU.

Motif Identification

MEME [61] was used to identify common motifs in midline and tracheal enhancers. We included previously identified midline enhancers for sim, Toll, slit [62], [63], rhomboid (rho) [50], btl [8], Vvl [64], roughest (rst) [65], [66], wrapper [67], gliolectin, organic anion transporter protein26f, liprin γ [59] and link [68], as well as the new midline enhancers reported here: CG33275, NetB, comm, escargot (esg) and Ectoderm3 (Ect3). The following previously identified tracheal enhancers were included: trh, Vvl early [34], Vvl autoregulatory [64], CG13196, CG15252, dys [58], btl [8], rho [50], link [68], and the new tracheal enhancers described here: CG33275, NetB, liprin γ, esg and moody.

Results

To understand how diverse genes are transcriptionally regulated in the midline, trachea or both tissues, we identified and compared enhancers of seven genes that are expressed during Drosophila development. The seven genes studied include three genes that encode axon guidance and synaptic proteins: liprin γ, comm and Net B; a gene in the EGFR signaling pathway, CG33275; a G protein coupled receptor, moody; a cell death gene, Ectoderm 3 (Ect3), and finally, the esg transcription factors. Several of these contain large introns and are separated from other genes by large intergenic regions and, therefore, to facilitate the identification of midline and tracheal enhancers, we searched for sequences conserved in a relatively large number of the sequenced Drosophila species [56]. We tested the ability of the conserved regions to drive expression in midline and tracheal cells by fusing them to GFP within the pHstinger or Mintgate enhancer tester vectors and generating transgenic fly lines. In certain cases, we also identified a minimal region capable of driving tissue specific expression. The composition and expression patterns of the identified enhancers are briefly summarized below.

CG33275

This gene is a guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor expressed in both the midline and trachea during embryogenesis [69], [70]. The entire gene spans approximately 47 kb and consists mostly of large introns (Fig. 2A). We identified an enhancer within the fifth intron of CG33275 capable of driving high levels of GFP in midline glia and a separate and distinct tracheal enhancer downstream of the midline enhancer (Fig. 2A and B). The midline enhancer was identified by testing reporter genes CG33275 ML2544:GFP, ML1312:GFP, ML753:GFP and ML577:GFP, and all but the CG33275 ML577:GFP reporter drove expression in midline glia (Fig. 2C–K), in a pattern similar to that of the endogenous gene [11]. The CG33275 ML753:GFP midline glial enhancer contains two regions conserved in 12 Drosophila species and one of these contains a CME (Fig. 2B). Sequences located just downstream of the midline enhancer drove high levels of GFP expression in a pattern similar to the endogenous gene [70]; in all tracheal cells beginning at stage 11 (Fig. 2L–N) and throughout larval stages (not shown). Both tracheal reporter genes CG33275 TRH2507:GFP (not shown) and the smaller CG33275 TRH1297:GFP reporter gene drove the same tracheal expression pattern (Fig. 2L–N). The CG33275 TRH1228:GFP reporter was not expressed in trachea or midline cells (not shown), whereas the CG33275 TRH265:GFP reporter was restricted to tracheal fusion cells (Fig. 2O–T), as demonstrated by the overlap in expression with dys (Fig. 2R–T). The CG33275 TRH2507:GFP reporter contains four CMEs, CG33275 TRH1297:GFP contains three of these and CG33275 TRH265:GFP contains one. All three of these reporters contain a region with a CME that is conserved across 12 Drosophila species (Fig. 2B). Dys, related to Trh, also heterodimerizes with Tgo and binds a site related to the CME, TCGTG, and can weakly interact with the sequences, TCGTG as well as the CME (Table 1) [58]. Consistent with this, the CG33275 TRH265:GFP enhancer expressed in fusion cells contains two TCGTG Dys/Tgo sites conserved in 12 Drosophila species. In summary, CG33275 contains separable, but adjacent midline and tracheal enhancers, and the tracheal enhancer contains a subregion that drove expression restricted to fusion cells.

Table 1. DNA recognition sequence of PAS heterodimers.

| Heterodimer | Name1 | Sequence2 |

| Sim/Tgo | CME | ACGTG |

| Trh/Tgo | CME | ACGTG |

| Dys/Tgo | TCGTG | |

| Dys/Tgo | GCGTG 3 | |

| Dys/Tgo | CME | ACGTG 3 |

| Sima/Tgo | HRE | RCGTG |

| Ss/Tgo | XRE | TNGCGTG |

| Per/Tim | E box | CACGTG |

| Clock/Bmal | E box | CACGTG |

1 The names of the recognition sites are indicated: CNS midline enhancer (CME), hypoxia response element (HRE), xenobiotic response element (XRE) and the E box is the recognition site for bHLH proteins. Similar (Sima) is the fly hypoxia inducible factor-α, Spineless (Ss) functions in bristle, leg and antennal development and Period (Per), Timeless (Tim), Clock and Bmal function in circadian rhythms.

2 The CGTG core sequences shared by each recognition site are italicized.

3 The GCGTG and ACGTG sites are likely low affinity sites for Dys/Tgo [58].

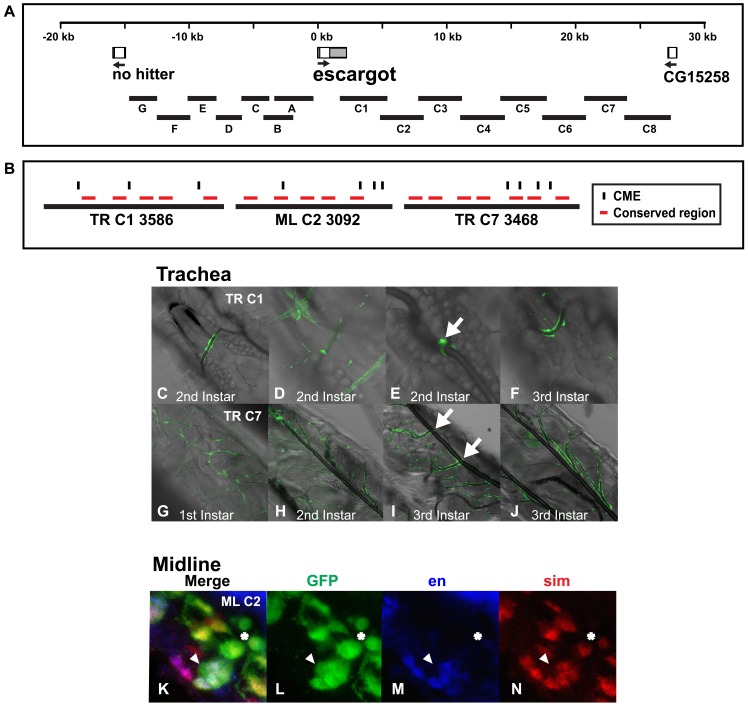

esg

esg is a zinc finger transcriptional repressor that regulates cell fate and development within the trachea and a subset of CNS cells, including the midline [35], [71]. esg is expressed at high levels in the embryo and moderate levels in the larval central nervous system, larval/adult midgut and adult testis [70], [72]. esg is rather isolated from other genes within the Drosophila genome and its next nearest upstream and downstream neighbors are ∼15–25 kb away (Fig. 3A). We examined this entire region to search for midline and tracheal enhancers and identified two, separable tracheal enhancers, esg TR C1:GFP (Fig. 3A–F) and esg TR C7:GFP (Fig. 3A, B and G–J) downstream of the coding sequence and another separable and distinct midline enhancer, esg ML C2:GFP (Fig. 3A, B and K–N), adjacent to and downstream of the esg TR C1 tracheal enhancer. The endogenous esg gene is expressed in tracheal fusion cells during embryogenesis and first detected during branch migration [73]. The tracheal enhancers identified here drive expression only late in embryogenesis and during larval stages. The esg TR C1:GFP reporter is expressed sporadically in fusion cells (Fig. 3C–F), while the esg TR C7:GFP reporter is expressed in all tracheal branches and fusion cells and sporadically in the dorsal trunks (Fig. 3G–J).

Figure 3. An esg genomic region contains a midline enhancer that is separable and distinct from two esg tracheal enhancers.

(A) Genomic regions surrounding esg used to generate the reporter constructs and (B) the esg enhancers are shown as above. Gray boxes represent 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. (C–J) Live larvae were analyzed by confocal and differential contrast microscopy and ventral views of the (C–F) esg TR C1:GFP and (G–J) esg TR C7:GFP reporters are shown. In larvae, the esg TR C1:GFP reporter is expressed sporadically in fusion cells (arrow in E) and the esg TR C7:GFP reporter is expressed in all tracheal branches and sporadically in the dorsal trunks (G–J), but consistently in fusion cells (arrows I). (K–N) Whole mount esg ML C2:GFP reporter embryos were stained with an anti-GFP antibody (green: L), engrailed monoclonal antibody (blue; M) and anti-sim antibody (red; N) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression is shown in the merge image (K). Anterior midline glia express GFP and sim and are located dorsally within the nerve chord. Posterior midline glia that normally undergo cell death during this time can still be visualized with GFP (three cells surrounding star in N), but not sim or engrailed. The MNB and its progeny express sim, engrailed and GFP and are located ventrally within the nerve chord (arrowheads in K–N). Lateral view of a stage 16 transgenic embryo is shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is on the left.

In addition, the esg ML C2:GFP reporter drove a unique expression pattern in the midline, where it is expressed in both anterior and posterior midline glia and the median neuroblast and its progeny (Fig. 3K–N). This pattern is consistent with that of the endogenous esg gene, known to be expressed in a subset of mesectodermal and midline primordial cells [11]. In addition to these three enhancers, we found additional esg enhancers that drove expression in other embryonic tissues (Table S3).

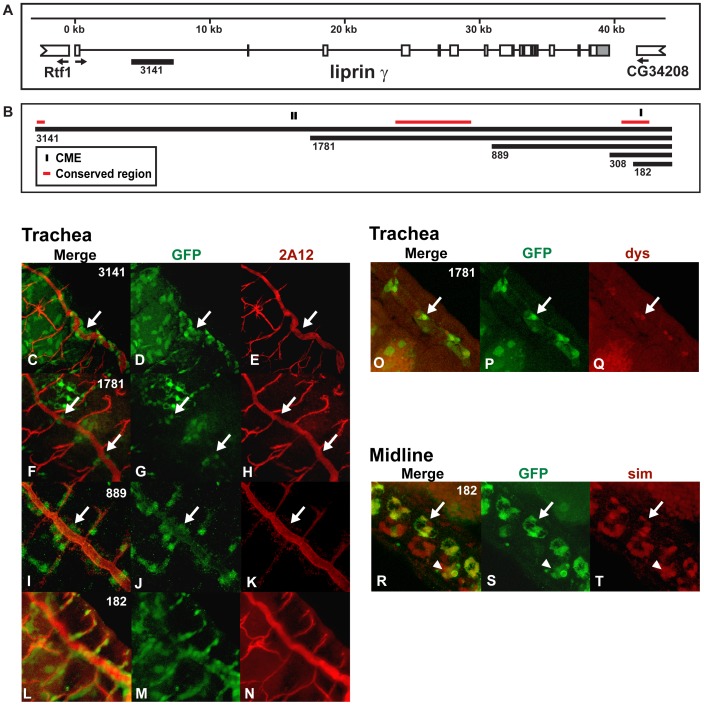

liprin γ

Liprin proteins interact with tyrosine phosphatases to regulate synapse formation. Drosophila contains three liprin genes and liprin γ is thought to antagonize the activity of the other two liprins: α and β at the synapse [74]. Our previous studies identified sequences within the liprin γ gene that drove expression in midline glia [59] and this same region drove expression in the embryonic and larval trachea (Fig. 4). This gene is expressed in both lateral and midline CNS glia at embryonic stage 14 [74] and several of the liprin γ reporter genes drove high levels of GFP expression during this stage and the remainder of embryogenesis. Both the liprin γ 3141:GFP (Fig. 4C–E) and liprin γ 1781:GFP (Fig. 4F–H) reporters drive expression in the dorsal trunk of the trachea, particularly within the posterior region of the embryo. The liprin γ 889:GFP reporter is expressed in additional tracheal cells, including the dorsal, visceral and lateral branches (Fig. 4I–K). Only the liprin γ 1781:GFP reporter drove expression in tracheal fusion cells (Fig. 4O–Q). The liprin γ 308:GFP reporter is expressed in the gut, but not in tracheal cells (data not shown), whereas the liprin γ 182:GFP reporter is expressed at high levels in all the trachea (Fig. 4L–N). In addition, this liprin γ 182:GFP reporter is sufficient to drive expression in midline glia and a few midline neurons, in a pattern that varies between segments (Fig. 4R–T). Therefore, the 182 bp core region contains a CME and conserved subregion that activates high levels of expression in both midline and trachea cells. Analysis of the expression pattern of the endogenous liprin γ gene indicates that it is either not expressed, or expressed at low levels, within the trachea during embryogenesis [70], [74]. This, taken together with 1) the high level of GFP expression in tracheal cells observed with the liprin γ 182:GFP reporter gene and 2) the diverse tracheal expression pattern of the larger liprin γ reporter genes, suggest that this region may only drive tracheal expression when isolated from surrounding sequences. Because multiple copies of the CME within a reporter gene, can drive expression in both the midline and trachea (see below), one function of sequences flanking the CME within enhancers is to limit expression of the gene to certain cell types. In summary, these experiments further define the minimal sequences needed for expression in the CNS midline within the previously identified liprin γ enhancer [59]. Moreover, these minimal sequences, when isolated from the genome and placed within reporter genes, can activate expression in tracheal cells as well.

Figure 4. Liprin γ contains a conserved enhancer sufficient to drive expression in both midline glia and trachea.

(A) The genomic regions within the first intron of liprin γ used to generate the reporter constructs and (B) the liprin γ enhancers are shown as in Fig. 1 and previously reported [59]. (C–T) Whole mount embryos were double-stained with an anti-GFP antibody (green: D, G, J, M, P and S) and monoclonal antibody 2A12 (red; E, H, K and N), anti-dys (red; Q) or anti-sim (red; T) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression is shown in yellow in the merge column (C, F, I, L, O and R). Even though the liprin γ 3141:GFP and liprin γ 889:GFP reporters are expressed in the dorsal trunk (arrows C–E and I–K) and dorsal and ventral branches, liprin γ 1781:GFP is restricted to mostly fusion cells of the dorsal trunk (arrows F–H and O–Q). The liprin γ 182:GFP reporter is expressed in all tracheal cells (L–N), midline glia (arrows R–T) and a few midline neurons in certain segments (arrowheads R–T). Lateral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is on the left.

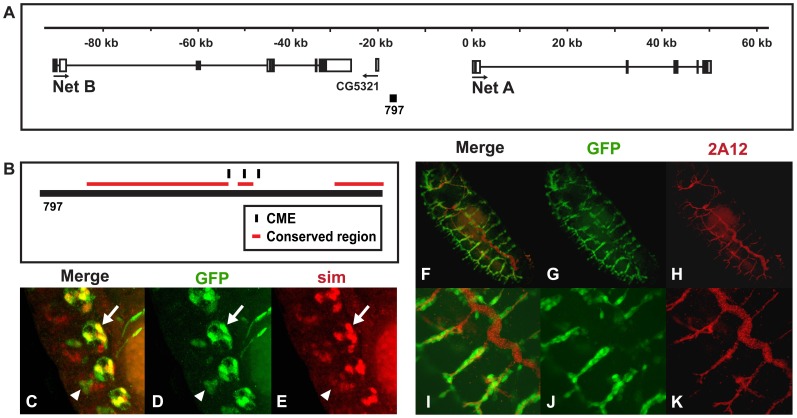

NetA and B

NetA and NetB are signaling molecules secreted by midline glia that attract axons to cross the midline and also function in glial migration [14], [15], [75], [76]. Both genes are expressed in many tissues, including midline glia [15], the larval trachea and adult nervous system [77]. The Net797:GFP reporter identifies a midline and tracheal enhancer located between NetA and NetB (Fig. 5A) that drove expression in midline glia (Fig. 5C–E) and trachea cells outside the dorsal trunk (Fig. 5F–K). This enhancer contains three CMEs and three highly conserved regions (Fig. 5B). Therefore, in contrast to the CG33275 and esg enhancers and similar to the liprin γ enhancer described above, the single Net enhancer drove expression in both the midline and trachea. Moreover, the tracheal expression pattern provided by this enhancer is unique and highest in the visceral and dorsal branches and low or absent in the dorsal trunks (Fig. 5F–K). We also identified several Net enhancers that drive expression in tissues outside the midline and trachea (Table S3).

Figure 5. Net contains an enhancer that drives expression in both midline glia and trachea.

(A) A genomic region located between NetA and NetB was used to generate a reporter construct and (B) the Net enhancer is shown. (C–K) Whole mount embryos were double-stained with an anti-GFP antibody (green: D, G and J) and anti-sim (red; E) or monoclonal antibody 2A12 (red; H and K) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression is shown in yellow in the merge column (C, F and I). The Net797:GFP reporter drove expression in midline glia (arrows C–E; ganglionic branches of trachea are also visible in the image in green) and occasionally midline neurons within some segments (arrowheads C–E). The tracheal expression pattern of this reporter is unique in that GFP is high in tracheal cells, except cells within the dorsal trunk (F–K). Lateral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is on the left.

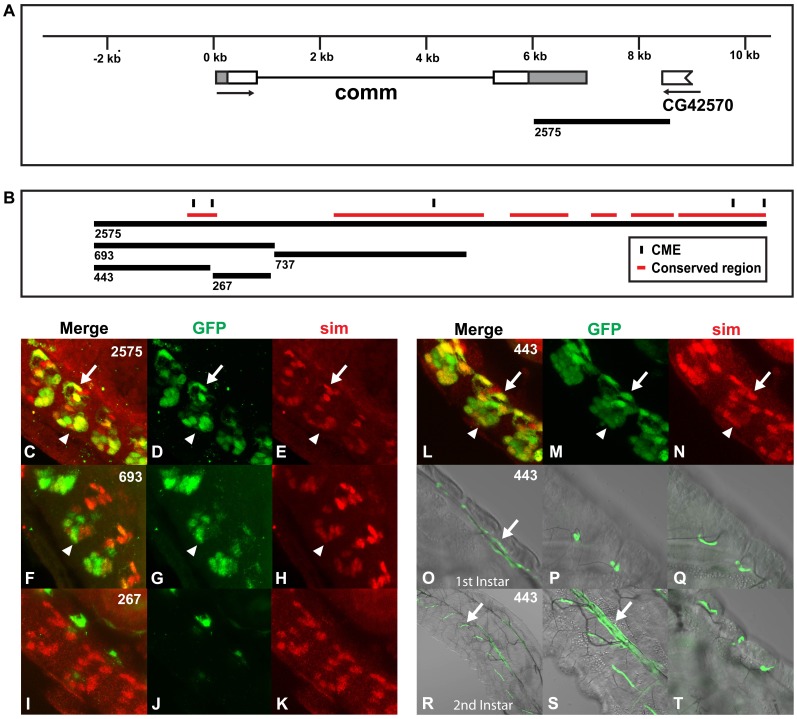

comm

comm functions in synapse assembly and axon guidance by controlling the subcellular localization of membrane receptors. In particular, comm controls the slit receptor, roundabout, as CNS axons navigate the midline to ensure they cross the midline only once [20], [22], [78]–[80]. comm is expressed at high levels in midline glia and transiently in lateral CNS axons [80]. A midline enhancer is located in the 3′ untranslated region of comm (Fig. 6A and B), identified by testing comm2575:GFP (Fig. 6C–E), comm737:GFP (not shown), comm693:GFP (Fig. 6F–H), comm443:GFP (Fig. 6L–N) and comm267:GFP (Fig. 6I–K). All but the comm737:GFP and comm267:GFP reporters drove expression in midline cells. Each of the reporters that are active in the midline drive GFP expression in slightly different subsets of midline cells: comm2575:GFP is expressed in midline glia, with variable expression in midline neurons (Fig. 6C–E), comm693:GFP is expressed predominantly in a subset of midline neurons (Fig. 6F–H) and comm443:GFP is expressed in all midline cells (Fig. 6L–N). Only the comm443:GFP reporter drove expression in the trachea and tracheal expression initiated during early larval development and persisted throughout all larval stages (Fig. 6O–T). Therefore, comm contains a single enhancer that drives expression in both the embryonic midline and larval tracheal cells.

Figure 6. The comm cis-regulatory region contains an enhancer that drives expression in the embryonic midline and larval trachea.

(A) Genomic regions surrounding and within comm were used to generate the reporter constructs and (B) the comm enhancer is shown. The closest gene upstream of comm is CG6244, which is 79,892 bp away. (C–N) Whole mount embryos were double-stained with anti-GFP (green: D, G, J and M) and anti-sim antibodies (red; E, H, K and N) and analyzed by confocal microscopy and the overlap in expression is shown in yellow in the merge column (C, F, I and L). (C–E) comm2575:GFP and (L–N) comm443:GFP are expressed in both midline glia (arrows) and midline neurons (arrowheads), while (F–H) comm693:GFP is restricted to some midline neurons (arrowheads). The comm267:GFP (I–K) and comm737:GFP (data not shown) reporters are not expressed in the midline. Lateral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is on the left. (O–T) comm443:GFP is also expressed in the tracheal dorsal trunks (arrows in O and S) as well as other tracheal branches (arrow in R). Live larvae containing the comm443:GFP reporter were analyzed by confocal and differential contrast microscopy and dorsal views are shown.

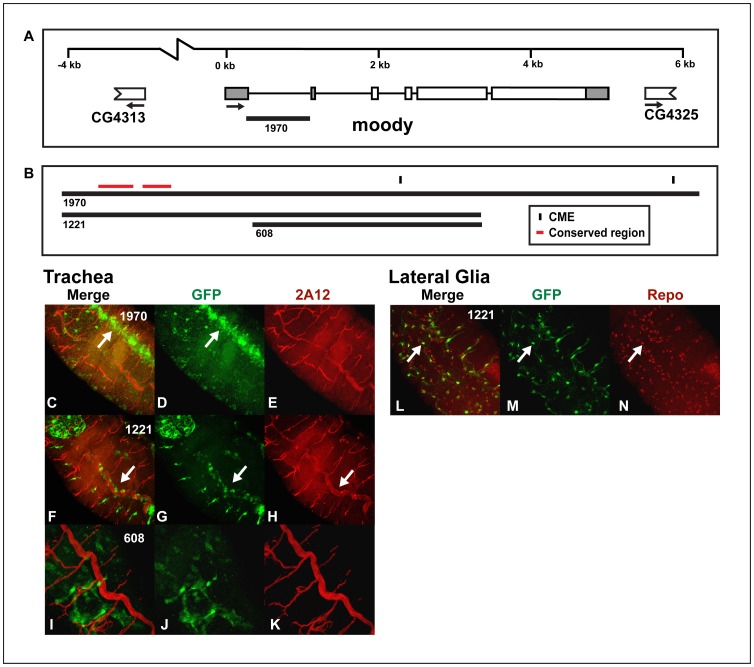

moody

moody is a rhodopsin and melatonin-like G-protein coupled receptor, found at the blood-brain barrier in adult flies [81] and that functions in germ cell migration in the embryo [82]. Moody is expressed in larval trachea, the larval/adult CNS, as well as many other tissues [77]. We tested three reporter genes: moody1970:GFP, moody1221:GFP and moody608:GFP (Fig. 7A and B) and found that moody1970:GFP is expressed in the dorsal vessel (Fig. 7C–E), but only moody1221:GFP drove expression in the dorsal trunks of the trachea, with expression highest in the posterior region of the embryo (Fig. 7F–H), similar to the liprin γ

Figure 7. The moody cis-regulatory region contains a tracheal enhancer that overlaps with a lateral CNS glial enhancer.

(A) The genomic regions surrounding and within moody used to generate the reporter constructs and (B) the moody enhancer is shown. (C–N) Whole mount embryos were double-stained with an anti-GFP antibody (green: D, G, J, and M) and monoclonal antibody 2A12 (red; E, H and K) or anti-repo monoclonal antibody (red; N) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression is shown in yellow in the merge columns (C, F, I and L). The expression patterns of the (C–E) moody1970:GFP, (F–H and L–N) moody1221:GFP and (I–K) moody608:GFP reporters are shown. Both the moody1970:GFP (not shown) and moody1221:GFP (L–N) reporters also drive expression in lateral glia as indicated by co-localization with repo (arrows). Additionally, moody 1221:GFP is expressed in the dorsal trunk (arrows F–H), while moody1970:GFP is expressed in the dorsal vessel (arrows C and D) and lightly in the dorsal trunk. (C–H) Dorsolateral, (I–K) lateral or (L–N) ventral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner.

3141 enhancer (Fig. 4C–E). Also similar to the liprin 3141:GFP enhancer [59], the moody1221:GFP (Fig. 7L–N) and moody1970:GFP (not shown) enhancers are expressed in lateral CNS glia. moody608:GFP drove expression in the fat body (not shown), but is not expressed in the trachea (Fig. 7I–K). The identified moody1221:GFP tracheal enhancer contains two CMEs, although they are not highly conserved. This enhancer does not drive midline expression, rather sequences within the moody enhancer restrict expression to the trachea.

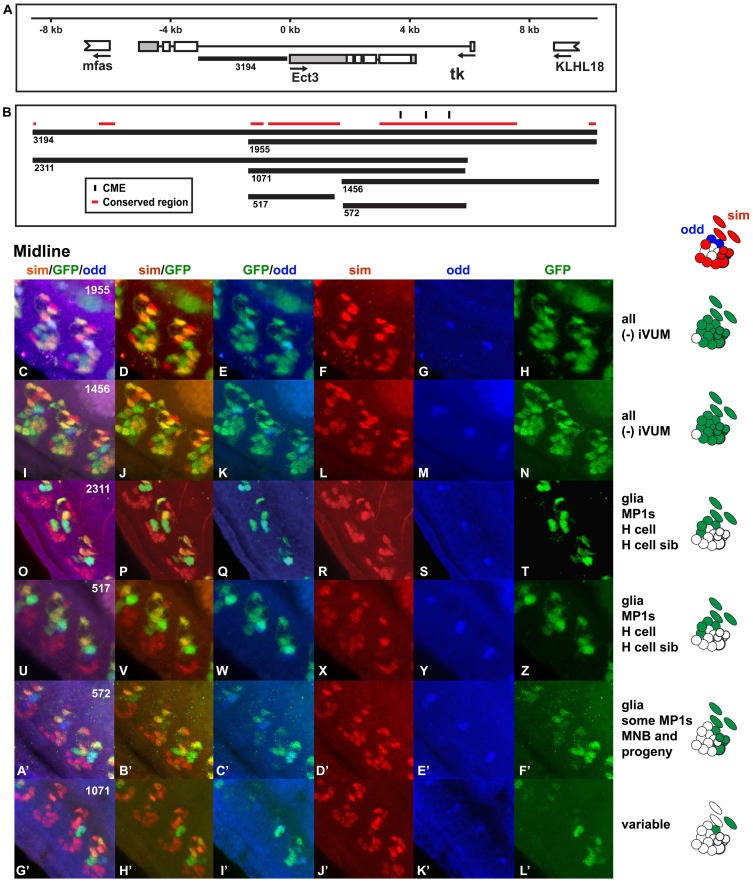

Ect3

The Ect3 protein is a galactosidase expressed in midline glia, [11] as well as other tissues, that regulates autophagic cell death [83]. Because Ect3 is located within the first intron of Tachykinin (Tk), the identified midline enhancer is found just upstream of Ect3 as well as within the first intron of Tk (Fig. 8A and B). Tachykinin (Tk) is a neuropeptide hormone expressed at high levels during 18–24 hours of embryogenesis, early larval stages and in the adult male [77]. The midline enhancer identified here likely regulates expression of the endogenous Ect3 gene, because only Ect3, and not Tk, is expressed in the embryonic midline [11], [70]. This midline enhancer is sensitive to small changes in sequence, such that various subregions drive different midline expression patterns. The Ect3 3194:GFP reporter contains the region bordered by the first exon of Tk on the 5′ end and the Ect3 transcription start site on the 3′ end (Fig. 8A and B). This reporter (not shown), as well as the Ect3 1955:GFP (Fig. 8C–H) and Ect3 1456:GFP (Fig. 8I–N) reporters drive high levels of GFP expression in all midline cells, with the exception of one iVUM neuron. Four other reporters are expressed in a more limited set of midline cells: 1) the Ect3 2311:GFP (Fig. 8O–T) and 2) Ect3 517:GFP (Fig. 8U–Z) reporters drove expression in midline glia, MP1 neurons, the H-cell and spotty and variable expression in the H-cell sib, while the 3) Ect3 572:GFP (Fig. 8A’-F’) reporter drove expression in some midline glia, MP1 neurons and some of the progeny of the MNB and 4) the Ect3 1071:GFP (Fig. 8G’-L’) reporter drove spotty and variable expression in only a few midline cells within some segments. Taken together, the data indicate the Ect3 enhancer contains sequences that promote expression in all midline cells. The endogenous Ect3 gene is expressed in midline glia [11] and all of the Ect3 reporters drive expression in these cells. The 572 bp Ect3 enhancer contains three CMEs and a highly conserved subregion that can combine with another, downstream subregion located within both the Ect3 1955:GFP and Ect3 1456:GFP reporters, to enhance expression in certain midline cells. In addition, the 517 bp region can drive expression in midline cells, despite the absence of any CMEs. Therefore, this region of the genome contains multiple subsections that combine to drive expression in midline cells.

Figure 8. The Ect3 cis-regulatory region contains a midline enhancer sensitive to context.

(A) The genomic region upstream of Ect3 (and within the first intron of Tk) used to generate the reporter constructs and (B) the Ect3 enhancers are shown. (C–L’) Whole mount embryos were stained with anti-sim (red; F, L, R, X, D’ and J’), anti-odd (blue; G, M, S, Y, E’ and K’) and anti-GFP (green: H, N, T, Z, F’ and L’) antibodies and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression is shown in the merge columns: all three antibodies (C, I, O, U, A’ and G’), sim and GFP (D, J, P, V, B’ and H’) and GFP and odd (E, K, Q, W, C’ and I’). Odd is expressed only in MP1 midline neurons. Both Ect3 1955:GFP (C–H) and Ect3 1456:GFP (I–N) drive expression in the all midline cells, with the exception of a single iVUM. Ect3 2311:GFP (O–T) and Ect3 517:GFP (U–Z) are restricted to some midline glia, MP1 neurons, the H cell and H cell sib. Ect3 572:GFP (A’–F’) is expressed in midline glia, some MP1 neurons and some of the MNB and its progeny. Finally, Ect3 1071:GFP (G’–L’) drives only spotty midline expression. Lateral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is on the left. The midline expression pattern of each reporter is shown schematically on the right.

In summary, ten enhancers were identified: six of the enhancers drove expression in the midline, seven in the trachea and three in both the midline and trachea (Table 2). CG33275 and esg each contain adjacent, separable midline and tracheal enhancers; whereas liprin γ, Net and comm each contain one enhancer that drove expression in both the midline and trachea. The moody enhancer drove expression only in the trachea and the Ect3 enhancer drove expression only in the midline. Despite providing expression in overlapping cell types, each enhancer drove a unique expression pattern within the midline and trachea. Next, these enhancers, together with previously reported enhancers discovered by several groups, were combined to search for overrepresented motifs that may correspond to binding sites for transcription factors that activate or repress genes in the midline and/or trachea.

Table 2. Ten identified midline and tracheal enhancers.

| Gene | Size1 | Position2 | Tissue | Midline cells3 | Tracheal cells4 |

| CG33275 | 753 | exon 5+ intron 5 | midline | glia (st. 13) | – |

| 1297/265 | intron 5 | trachea | – | all (st. 11)/fusion cells (st. 13) | |

| esg | 3092 | ∼ 5 kb downstream | midline | glia, MNB and progeny (st.12) | – |

| 3586 | downstream | trachea | – | larval fusion cells (1st instar) | |

| 3468 | ∼ 20 kb downstream | trachea | – | larval fusion cells; secondary branches (1st instar) | |

| liprin γ | 889/182 | intron 1 | both | glia (st. 12)/glia and sporadic in MNB and progeny (st. 12) | DT(st. 15)/all (st. 13) |

| Net | 797 | ∼ 10 kb downstream | both | mostly glia (st. 12) | all but DT (st. 12) |

| comm | 443 | 3′ untranslatedregion | both | all midline cells (st. 10) | larval dorsal trunk and some secondary branches (st. 17) |

| moody | 1221 | intron 1 | trachea | – | posterior DT (st. 15) |

| Ect3 | 517 | upstream of Ect3/intron 1 of Tk | midline | glia, MP1s, H cell and H cell sib (st. 10) | – |

1 The size of the minimal fragment with enhancer activity,

2 the position of the enhancer relative to the gene and 3midline and 4tracheal cells that exhibit enhancer activity are indicated.

3,4 The stage of development when reporter expression is first observed is indicated in parentheses. The absence of expression in the midline or trachea is indicated with a dash.

Proximal CME Sequences

A longterm goal is to use the midline and trachea as models to study how transcription factors combine with cell type specific co-factors to regulate unique gene sets, and, in this way, dictate development of unique tissues. Including the ten enhancers identified here, nineteen different midline enhancers and nineteen tracheal enhancers have been identified. To identify sequences that promote or inhibit CME utilization in either the midline or trachea, we analyzed the enhancers in two different ways. First, we searched sequences directly flanking the CME within defined enhancers to determine if these sequences could predict whether a particular CME is utilized by Sim/Tgo or Trh/Tgo and secondly, we searched the smallest region sufficient to drive expression in a tissue for reiterated motifs that may help restrict or promote gene expression in the midline and trachea.

Results from this analysis indicate that the nucleotide located both immediately upstream and downstream of the CME are strong, but not absolute, determinants of whether the CME is utilized in the midline or trachea (Table 3). We found sixty-six CMEs within all the enhancers examined here and 34/66 consisted of the sequences AACGTGC, TACGTGA or TACGTGC (CME underlined), while the sequences AACGTGG, GACGTGT, TACGTGG were not found in any of the enhancers, suggesting that Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo may not bind these sequences (Table S4). Enhancers that drive only midline expression, most often contain the sequence (A/G/T)ACGTGC, while enhancers that solely drive tracheal expression contain the sequence (A/T)ACGTG(A/C/T) and enhancers that function in both the midline and trachea, most often contain the consensus (A/T)ACGTGC (Table 3). Therefore, the nucleotides immediately flanking the core CME may be one determinant that controls if a PAS heterodimer will bind this sequence within different cell types. We further investigated this by constructing and testing the expression pattern of synthetic reporter genes.

Table 3. Proximal CME context in midline and tracheal enhancers.

| Mostcommon1 | Number2 | Neverfound3 | Tissue4 | PredictedConsensus5 |

| A ACGTG C | 14 | A ACGTG G | midline | (A/G/T) ACGTG C |

| T ACGTG A | 10 | G ACGTG T | trachea | (A/T) ACGTG (A/C/T) |

| T ACGTG C | 10 | T ACGTG G | both | (A/T) ACGTG C |

Sixty-six CMEs were found in all midline and tracheal enhancers examined. 1The nucleotides found directly 5′ and 3′ of the CME within the enhancers and 2 the number of times that sequence was found in all the midline and tracheal enhancers are listed. The three sequence contexts found in the left column represent 52% of the CMEs found within all enhancers (34/66; Table S4), while 3other sequence contexts were not found in any enhancers. 4, 5Sequences flanking the sixty-six CMEs were used to derive a consensus sequence for genes expressed in the midline, trachea or both tissues.

Synthetic Genes

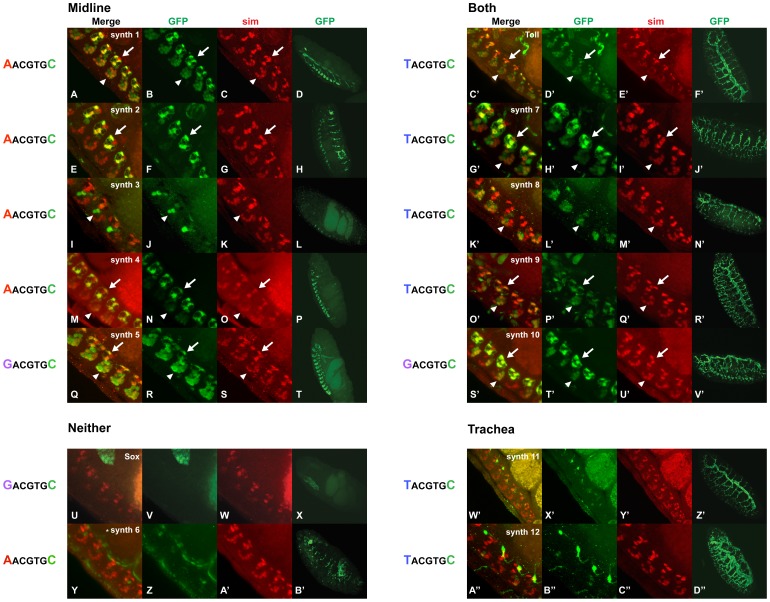

Enhancers are modular and contain multiple binding sites for many activators and repressors that work together in large multi-protein complexes to regulate transcription in different cell types. Nevertheless, individual binding sites of a limited number of transcription factors are sufficient to drive expression in certain tissues, particularly when present in more than one copy. Relevant to this study, four copies of the CME fused to β-galactosidase or GFP, is sufficient to drive reporter expression in both the midline and trachea [7], [8], [59], [63]. Our previous results indicated that the context surrounding the CME within such multimerized constructs had a large impact on the reporter gene expression pattern [59]. To confirm and extend the results obtained with endogenous enhancers, we analyzed the expression pattern of additional synthetic reporters (Table 4). The synthetic sequences were modifications of CMEs derived from either the wrapper (synth 1–4 and synth 6) or Toll midline enhancers (synth 5, Toll and synth 7–12). We chose these particular sequences because both had been tested previously within synthetic reporter genes and drove different patterns of expression. The CME and flanking sequences found in the wrapper enhancer, when multimerized four times, drives expression only in the midline [59], while the CME and flanking sequences found in the Toll enhancer drives expression in both the midline and trachea [62].

Table 4. Sequence of synthetic reporter constructs.

| Midline only | |

| synth 1 | ATTACACTCTCCGCTTCAGAGAACGTGCTGCTGTTGCATATTCCGA |

| synth 2 | TTCAGAGAACGTGCTGCTGTTGCATATTCCGAGATAAAATGTCATTGT |

| synth 3 | GCGACACTCTCCGCTTCAGAGAACGTGCTGCTGTTGCATATTCCGA |

| synth 4 | ATTACACTCTCCGCTTCAGAGAACGTGCTGCTTAAAA |

| synth 5 | TATGCACAATGACATTTAGCAGAAATTCAGACGTGCCACAGACCA |

| Neither Midline nor Trachea | |

| Sox | CACAATGACGTGCCACAGA |

| synth 6 | ATTACACTCTCCGCTTCAGAGAACGTGCTGCTGGCGCATATTCCGA |

| Both Midline and Trachea | |

| Toll | AAATTTGTACGTGCCACAGA |

| synth 7 | AAATTTGTACGTGCCACAGATAATTA |

| synth 8 | AAATTTGTACGTGCCACAGAGTTGCAT |

| synth 9 | AAATTTGTACGTGCCACAGAGGCGTGGGAACCGAGCTGAAAGTAAGTTTCTCACACA |

| synth 10 | ACAATGACATTTCAGACGTGCCACA |

| Trachea only | |

| synth 11 | AAATTTGTACGTGCTTTTTATCTCTGAAGCGGAGAGTGTAAT |

| synth 12 | AAATTTGTACGTGCCACAGAGGATGCACCCACGAGCTGAAAGTAATGGGCCACCA |

Sequences of synthetic constructs multimerized four times and fused to GFP within reporter constructs are listed according to the tissue that expressed each synthetic reporter (Fig. 9). The CME is enlarged within each sequence. Sites important for midline expression within the wrapper enhancer [67] are underlined in synths 1 – 6 and include putative binding sites for Sox (ATTGT), pointed (CTCTCCG) and unknown (AAAA) transcription factors. Binding sites for engrailed (TAATTA), Vvl (TTGCAT) and Suppressor of Hairless (GTGGGAAC CGAGCTGAAAGTAAGTTTCTCAC ) were added to the Toll CME sequence and shown in bold in synths 7 – 9.

To understand which sequences within the previously published synthetic constructs are responsible for the two different expression patterns, we tested additional synthetic reporter genes. The sequence context surrounding the CME in the wrapper enhancer was tested using two approaches. First, the 70 bp minimal wrapper enhancer was divided into two sections and tested independently: synth 1 contained sequences 7–53 and synth 2 contained sequences 28–70 of the wrapper minimal enhancer. Both of these constructs contain the single CME and flanking sequences found in the wrapper enhancer and both of these multimerized reporters were expressed in the midline, but not the trachea (Fig. 9A–H). However, the expression pattern within the midline differed and synth 1 drove expression in all midline cells (Fig. 9A–C), while synth 2 drove expression restricted to the midline glia (Fig. 9E–G). Next, we tested specific sequences within these constructs. When the ATTA sequence found at the 5′ end of synth 1 is changed to GCGA within synth 3, the reported gene is still expressed in the midline, but only in 1–3 cells per segment (Fig. 9I–L), suggesting this may have created a repressor binding site that limits midline expression. In contrast, changing the 14 nucleotides found at the 3′ end of synth 1 (GTTGCATATTCCGA) to TAAAA within synth 4, had only a small effect on the midline expression pattern of GFP (compare synth 1 in Fig. 9A–C with synth 4 in Fig. 9M–O), while changing the first three nucleotides within this 14 bp region from GTT found in synth 1 to GGC within synth 6 almost completely eliminated midline expression (Fig. 9Y–B’).

Figure 9. Proximal sequence context flanking the CME contributes to the midline and tracheal expression pattern.

Whole mount transgenic embryos containing one of the multimerized synthetic reporter constructs were labeled with anti-GFP (green; B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V, X, Z, B’, D’, F’, H’, J’, L’, N’, P’, R’, T’, V’, X’, Z’, B’’ and D’’) and anti-sim (red; C, G, K, O, S, W, A’, E’, I’, M’, Q’, U’, Y’ and C’’) antibodies and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The overlap in expression between GFP and sim is yellow (merge; A, E, I, M, Q, U, Y, C’, G’, K’, O’, S’, W’ and A’’). Midline GFP expression is driven by the (A–D) synth 1:GFP, (E–H) synth 2:GFP (I–L) synth 3:GFP, (M–P) synth 4:GFP and (Q–T) synth 5:GFP, whereas the (U–X) Sox:GFP and (Y–B’) synth 6:GFP reporters are not expressed in either the midline or trachea. The (C’-F’) Toll:GFP, (G’-J’) synth 7:GFP, (K’-N’) synth 8:GFP, (O’-R’) synth 9:GFP and (S’-V’) synth 10:GFP synthetic reporters are expressed in both the midline and trachea, whereas the expression pattern of the (W’-Z’) synth 11:GFP and (A’’-D’’) synth 12:GFP reporters are restricted to trachea only. The expression patterns of the Toll:GFP and Sox:GFP reporters were previously reported [59]. Note that midline GFP expression driven by the (A–D) synth 1:GFP, (M–P) synth 4:GFP, (Q–T) synth 5:GFP, (C’-F’) Toll:GFP, (G’-J’) synth 7:GFP, (O’-R’) synth 9:GFP and (S’-V’) synth 10:GFP reporters is in both neurons and glia, whereas expression driven by the (E–H) synth 2:GFP reporter is restricted to midline glia and expression of the (I–L) synth 3:GFP and (K’-N’) synth 8:GFP reporters is restricted to midline neurons. The immediate CME context within each synthetic sequence is indicated to the left of the images and the entire sequence of each synthetic reporter construct is listed in Table 4. Arrows indicate midline glia and arrowheads indicate midline neurons. Lateral or ventrolateral views of stage 16 transgenic embryos are shown; anterior is in the top, left hand corner and ventral is bottom, left. Four copies of each synthetic sequence were tested within the reporter constructs.

As mentioned above, the multimerized Toll CME and flanking sequences drives reporter expression in all midline and tracheal cells [62] (Fig. 9C’–F’). We tested whether adding binding sites of known midline transcription factors affected the expression pattern of this synthetic reporter gene. For this, an Engrailed binding site (TAATTA; [84]) was added to synth 7, a binding site for the POU domain transcription factor, Vvl (GTTGCAT; [64]) was added to synth 8 and binding sites for the Suppressor of Hairless transcription factor (CGTGGGAACCGAGCTGAAAGTAAGTTTCTCACACA; [85]) within sythn 9 (Table 4). Surprisingly, none of these changes in sequence affected the expression pattern of the Toll CME reporter and all of the reporters were expressed in the trachea (Fig. 9C’–R’), although synth 7, was expressed at a lower level in the dorsal trunks relative to the rest of the trachea; a pattern not observed with the other reporters (Fig. 9J’). These nucleotide changes also did not eliminate the midline expression pattern, although synth 8, containing the Vvl binding site, drove expression in midline neurons, but not midline glia (Fig. 9K’–M’).

In summary, four of five synthetic constructs containing the sequence AACGTGC, were expressed in midline cells only (Fig. 9A–P and Table 4), while the fifth was not expressed in either the midline or trachea (Fig. 9Y–B’). Four of six synthetic constructs containing the related sequence, TACGTGC, drove expression in both midline and tracheal cells (Fig. 9C’–R’) and the other two drove expression only in trachea (Fig. 9W’–D’’). Finally, three synthetic genes containing the sequence, GACGTGC, each exhibited a different expression pattern: synth 5 was expressed only in the midline (Fig. 9Q–T); Sox in neither tissue (Fig. 9U–X) and synth 10 in both the midline and trachea (Fig. 9S’–V’), suggesting that this sequence is more sensitive to effects of additional sequences flanking the CME, compared to the other contexts. Taken together, the results suggest that the nucleotides immediately upstream and downstream of the CME had the largest impact on whether GFP was expressed in the midline or trachea. In most cases, the spacing and sequences between the CMEs did not affect whether or not the synthetic reporter was expressed in the midline or trachea, but instead, these sequences controlled which cell types within the midline or trachea, expressed GFP. These results, together with those of the endogenous enhancers suggest that sequences proximal to the CME are strong, but not absolute, predictors of midline or trachea expression. Additional sequences, more distal to the CME, also impact CME utilization, as well as control which cell types express the gene.

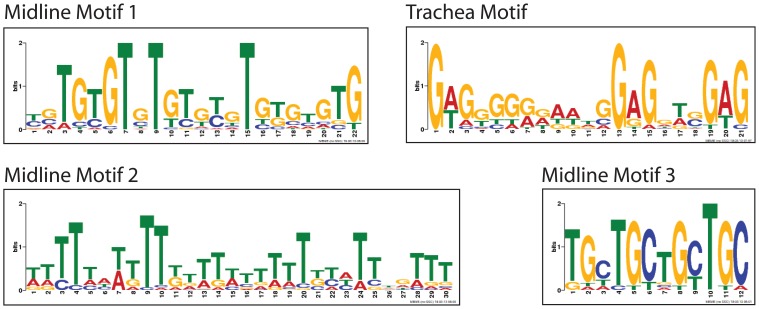

Identification of Overrepresented Midline and Tracheal Motifs

To identify motifs other than the CME overrepresented within midline and tracheal enhancers, we used MEME (http://meme.ebi.edu.au/meme/cgi-bin/meme.cgi; [61]). Examination of enhancers that drive expression in both tissues together with enhancers that drive expression only in the midline identified three overrepresented midline motifs (Fig. 10 and Table 5). In addition, MEME analysis of enhancers expressed in both tissues together with enhancers that drive expression only in the trachea, led to the identification of a single overrepresented tracheal motif. All four motifs consist of simple sequence repeats: midline motif 1 is 22 bp long, consists of repeating TG residues and is present 18 times in the 19 midline enhancers; midline motif 2 is 31 bp, consists mostly of T residues and is found 50 times; and midline motif 3 is 12 bps, consists of four repeats of the trinucleotide TGC and is found 25 times. The identified tracheal motif is 22 bp long, consists mostly of G residues and is found 16 times in the 19 tracheal enhancers examined. To ensure these results were not biased by including enhancers of variable sizes (336–3586 bp), we compared the above results to those obtained after restricting the search to only the smallest midline and tracheal enhancers identified, and excluded enhancers that function in both tissues. The same motifs were identified using this approach.

Figure 10. Motifs overrepresented in midline and tracheal enhancers identified with MEME.

MEME [61] was used to identify motifs overrepresented in midline and tracheal enhancers. The expected number of motifs one would find in a similarly sized set of random sequences (E-value) and the number of times each site was found within the enhancers are indicated in Table 5. Each motif was identified using two, related data sets (see text).

Table 5. Midline and tracheal motifs identified with MEME.

| Motif Name | 3Number of enhancers examined | 4Number of enhancers containing site | 5E value | 6Total number of sites | 7Length of site |

| 1midline 1 | 19 | 9 | 1.2 e-05 | 18 | 22 |

| 1midline 2 | 19 | 14 | 7.2 e-34 | 50 | 31 |

| 1midline 3 | 19 | 12 | 1.2 e-10 | 25 | 12 |

| 2trachea 1 | 19 | 8 | 1.4 e-10 | 16 | 22 |

MEME analysis was used to identify motifs overrepresented in midline and tracheal enhancers. Three motifs were found in midline enhancers and one in tracheal enhancers (Fig. 10). Results from1twelve enhancers that drive expression in the midline together with seven enhancers that drive expression in the midline and trachea or 2twelve enhancers that drive expression in the trachea and seven enhancers that drive expression in the midline and trachea are shown, as well as. 3the number of enhancers examined, 4number of enhancers containing the motif, 5likelihood of finding the motif by chance, 6number of times the site was found in all the enhancers examined and. 7length of the identified site.

Discussion

DNA sequences located within introns and intergenic regions are known to regulate transcription and package DNA; however, many aspects of these processes remain unknown. Enhancers that control gene expression patterns are modular and contain binding sites for transcription factors that function in a combinatorial manner [86]–[90]. The array of transcription factors expressed within a particular cell type, and available to bind enhancers, depends upon the cell’s position in the embryo as well as its developmental history. Identifying shared properties of enhancers active within a given cell type is challenging because most genes display their own unique expression pattern. Moreover, transcription factor binding sites can be combined in multiple ways to generate a similar expression pattern [91]. As a result, the complexity of gene expression patterns is often reflected by a complex and unpredictable organization of cis-regulatory sequences. Untangling this complexity to reveal how enhancers integrate positional, environmental and physiological information to regulate gene expression is needed to understand how organisms adapt to their internal and external environments at the molecular level.

Each enhancer described here contained a unique constellation of transcription factor binding sites and, as a result, drove a unique expression pattern in midline and tracheal cells. By analyzing and comparing available midline and tracheal enhancers, we have identified sequences, both proximal and distal to the CME, which promote expression in one tissue or the other. These reporters can be exploited in the future to identify transcription factors that bind to the enhancers using techniques such as chromatin immunoprecipitation, the yeast one hybrid assay and mutant genetic backgrounds. In addition, over one thousand GAL4 lines have been identified that drive expression in embryonic midline cells [92], providing a rich resource for extending these studies.

We have identified enhancers that drive expression restricted to midline glia, midline neurons, all embryonic tracheal cells, tracheal fusion cells, the posterior dorsal trunk, lateral tracheal branches, terminal cells or larval trachea cells and are activated at different stages of development (Table 2). In addition to identifying new motifs that may bind characterized or novel transcription factors, these studies provide tools for expressing transgenes in specific midline and tracheal subtypes for experimental purposes. When combined with toxins, RNAi or fluorophores, these sequences can be used to ablate cells, knockdown expression of specific genes and/or specifically label midline or tracheal subtypes. Moreover, genes within orthologous vertebrate tissues, such as glia and blood vessels, are regulated by similar regulatory networks [6]. Comparing midline and tracheal regulatory networks with networks that impact related tissues in other organisms will reveal how functionally distinct tissues are generated.

Midline and Tracheal Enhancer Motifs

Several families of transcription factors contain members that bind related, but slightly different DNA recognition sequences. Examples include members of the nuclear receptor family (reviewed in [93]) and bHLH proteins [94], [95]. Nuclear receptor homodimers and heterodimers bind DNA response elements consisting of two inverted repeats separated by a trinucleotide spacer. Specificity is determined by interactions between protein loops on the second zinc finger of a particular steroid receptor DNA binding domain and the trinucleotide spacer within the DNA recognition site [96], [97]. Similarly, the recognition sequence of bHLH transcription factors is called the E box and consists of the sequence CANNTG [98]. Specific bHLH heterodimers preferentially bind E boxes containing various internal dinucleotides (represented by the NN within the E box) [99]. The bHLH-PAS proteins investigated here are a subfamily within the bHLH superfamily of transcription factors. The PAS domain helps stabilize protein-protein interactions with other PAS proteins, as well as with additional co-factors, some of which mediate interactions with the environment [53]–[55]. The evolutionary relationship of bHLH and bHLH-PAS proteins is also reflected in the similarity of their DNA recognition sequences. The CME is related to the E box and historically has been considered to consist of a five rather than six base pair consensus (Table 1). Previous results indicated bHLH-PAS heterodimers strongly prefer the internal two nucleotides of the binding site to be “CG”, while the nucleotide immediately 5′ to this core helps to discriminate which heterodimer binds the site. The first crystal structure of a bHLH-PAS heterodimer bound to DNA reveals that the recognition sequence of the human Clock/Bmal bHLH-PAS heterodimer actually consists of seven base pairs, rather than five [100]. This is consistent with results reported here that suggest Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo heterodimers preferentially bind highly related, but slightly different seven base pair sequences (Tables 3 and 4). In addition, experiments with fly Sim and human Tgo, called Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein (Arnt), using the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) approach, identify the sequence DDRCGTG (D = A, C or T and R = either purine) as the Sim/Tgo binding site [101]. Our results agree with this, although the consensus sequence we identify by examining known enhancers, is shifted by one nucleotide (DACGTG C; Table 3). In the midline and tracheal enhancers, we found sixty-six copies of the CME, ACGTG, and forty-eight copies of the related sequence, GCGTG, also identified in the SELEX experiments (Table S5). Half of these GCGTG sites fit the seven bp consensus TGCGTGR and future experiments are needed to determine their importance within the various enhancers. Our results indicated that the CME context favored within midline and tracheal enhancers as well as enhancers active in both tissues, was very similar (Table 3), yet clearly distinct from binding sites of other bHLH and bHLH-PAS heterodimers (Table 1). Based on the expression pattern of certain reporter genes examined here, the same CME may be bound by Sim/Tgo in the midline and Trh/Tgo in the trachea within certain enhancers. Within other contexts, the CME appears to be discriminated by these different heterodimers, because some enhancers drive expression in only one tissue or the other.

Enhancer Complexity

Results from both endogenous enhancers and the synthetic reporter genes confirm the importance of the proximal sequences in limiting expression to either the midline or trachea. While the proximal context of the CME plays a role, additional sequences clearly combine with the CME to ultimately determine if an enhancer is functional in the midline or trachea. Taken together, these results indicate that proximal motifs combine with additional sequences not only to determine whether or not a gene is expressed in the midline or trachea, but also to determine which cellular subtypes express the gene and when it is activated within a tissue. Future experiments will reveal if 1) changing the sequence, AACGTGC, to TACGTGC within a midline enhancer will cause the enhancer to drive expression in trachea as well and 2) if changing the sequence, TACGTGC, to AACGTGC within an enhancer that drives expression in both the midline and trachea, will restrict expression to only the trachea. Sequences proximal to the CME likely affect the affinity of either Sim/Tgo and/or Trh/Tgo heterodimers to the DNA, but binding sites for additional factors that interact cooperatively to stabilize an entire transcription complex are needed for high levels of expression within a particular cell. Moreover, recent experiments indicate that enhancers containing multiple CMEs are activated earlier in the embryonic midline than enhancers containing only one CME [102]. The authors of this study suggest Sim/Tgo binding sites may be sufficient for activation in the early embryo, but that binding sites for additional transcription factors must combine with the CME to drive expression within the later, more complex embryo.

The experiments described here as well as previous experiments indicate that the CME is not always necessary for either midline or tracheal expression. A number of enhancers that drive expression in both tissues do not contain a CME, including: 1) a 517 bp autoregulatory Vvl enhancer that drove expression in both the midline and trachea [64], 2) another, separate tracheal enhancer of Vvl [34], 3) a trh autoregulatory enhancer 4) the link enhancer, after its sole CME has been destroyed [68], 5) a dys tracheal enhancer [58], 6) a tracheal enhancer of CG15252, 7) a tracheal enhancer of CG13196, and 8) the 517 bp Ect3 midline enhancer described here (Fig. 8). These sequences may be capable of driving midline and tracheal expression due to the presence of unknown, low affinity binding sites for Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo, or binding sites for other midline and tracheal transcription factors that can help recruit PAS heterodimers to the enhancer. To understand how a combination of binding sites that does not include the CME can drive expression in the midline and trachea, as well as how CMEs are distinguished by Sim/Tgo and Trh/Tgo heterodimers, we searched and found other regulatory motifs, both proximal and distal to the CME in midline and tracheal enhancers. Future experiments are needed to understand how Sim and Trh interact with additional factors to modify chromatin structure, and ongoing mutagenesis experiments will help reveal roles for the identified T, TG and G rich regions within midline and tracheal enhancers (Fig. 10). These repetitive motifs are found scattered throughout the enhancers and do not appear to have a fixed location relative to the CMEs. AT rich regions bend and denature relatively easily, facilitating DNA looping and are often found in cis-regulatory regions. The short, repetitive regions identified here may interact with specific transcription factors, such as Sox, Forkhead-type or other remodeling proteins to open chromatin [103], [104]. Alternatively, these regions may be involved in 1) recruiting transcription factors after replication, 2) nucleosome positioning and/or 3) binding of histone modification enzymes to enhance transcription; all of which may affect quantitative and qualitative genetic variation in expression [105]. In addition, results with multiple transgenic lines indicate the synthetic constructs show little variation in patterns and levels and consistently recruit Sim/Tgo and/or Trh/Tgo regardless of insertion site. This suggests that factors interacting with these relatively small multimerized sequences (20–57 bp) are sufficient to open chromatin to allow for efficient transcription. Taken together, results from a number of labs suggest the following enhancer characteristics combine to determine if a gene will be expressed in the midline or trachea: 1) the number of CMEs within the enhancer, 2) the proximal context surrounding each CME and 3) binding sites for additional activators, repressors and/or factors that affect chromatin structure.

Evolution of Sim and Trh Developmental Functions

While these experiments focus on the cis-regulatory sequences that control the expression of genes within the midline and trachea, they do not address why many genes are expressed in both of these tissues and regulated by related PAS heterodimers. It is predominantly genes expressed in the CNS midline glia, rather than the midline neurons, that are also expressed in tracheal cells. PAS proteins perform diverse functions across all biological kingdoms and most characterized members function as environmental sensors [53]–[55]. Historically, Sim and Trh have been considered exceptions and their developmental functions have been emphasized [106]. However, functions of Sim and Trh may have arisen in ancestral organisms that more closely resemble the adult form of Drosophila, a stage when Sim and Trh may function more similarly. For instance, in adult flies, both glia and trachea provide support and energy to neurons and trh is expressed in the CNS late in embryogenesis and throughout the remainder of the fly’s life. In the adult fly brain, tracheal development is guided by glial cells, and ablating glia causes the trachea to branch more extensively within this tissue [107]. Related mechanisms that guide glia and trachea distribution in the brain may explain, in part, shared gene regulatory pathways, including those regulated by the related PAS proteins, Sim and Trh. Most of the Drosophila PAS proteins that interact with Tgo are expressed in the trachea, including Trh, Dys and Similar (the fly version of HIF-1α), and Sim likely descended from a common ancestral gene. Developmental functions of Sim and Trh may have arisen later than their adult functions and common ancestral functions of these two tissues in the adult may explain why many enhancers drive expression in both the midline and trachea and why other midline and tracheal enhancers are closely linked. Further dissecting the similarities and differences in gene regulation within the CNS midline and trachea will reveal novel molecular mechanisms used to construct these tissues during development. Additional experiments are also needed to understand how signaling pathways combine with Sim and Trh to regulate genes in midline glia and trachea, not only in embryos, but also in larvae and adults, under different environmental conditions.

Supporting Information

List of PCR primers used to generate fragments of the CG33275 , esg, liprin γ, Netrin, comm, moody and Ect3 genes that were tested for their ability to drive midline and tracheal transcription. Restriction sites introduced for cloning purposes are indicated in lower case.

(DOC)

List of PCR primers used to generate the synthetic reporter genes tested for their ability to drive midline and tracheal transcription. The 1 Toll and Sox synthetic reporters have been previously reported [59]. Engineered restriction sites used to ligate and subclone the synthetics are shown in lower case.

(DOC)

For each enhancer, 1the name of the enhancer, 2the tissue that expressed GFP driven by the enhancer, and 3,4PCR primers used to generate the enhancers derived from esg and Netrin genes are listed. Restriction sites introduced for cloning purposes are indicated in lower case.

(DOC)

Listed is the immediate context of CMEs found within enhancers that drive expression in 1the midline, 2the trachea or 3both tissues. For each CME (ACGTG), 4the gene where it is found, 5the number of CMEs within each enhancer and the 6seven bp sequence of the site are shown. 7The total number of CMEs found within the enhancers examined is indicated at the bottom of the table.

(DOC)

Listed is the immediate context of GCGTG motifs found within identified enhancers that drive expression in 1the midline, 2the trachea or 3both tissues. For each GCGTG motif, 4the gene where it is found, 5the number found within each enhancer and the 6seven bp sequence of the site are shown. 7The total number of CMEs found within the enhancers examined is indicated at the bottom of the table.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Trudy MacKay and Faye Lawrence for support and help with fly maintenance, Jim Skeath for antibodies and Laura Mathies for critically reading the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by grants 0416812 and 0750620 from the National Science Foundation Grants website: http://www.nsf.gov/. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Nambu JR, Lewis JO, Crews ST (1993) The development and function of the Drosophila CNS midline. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology a-Physiology 104: 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nambu JR, Lewis JO, Wharton KA, Crews ST (1991) The Drosophila single-minded gene encodes a helix-loop-helix protein that acts as a master regulator of CNS midline development. Cell 67: 1157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas JB, Crews ST, Goodman CS (1988) Molecular genetics of the single-minded locus: A gene involved in the development of the Drosophila nervous sytem. Cell 52: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Isaac DD, Andrew DJ (1996) Tubulogenesis in Drosophila: A requirement for the trachealess gene product. Genes & Development 10: 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilk R, Weizman I, Shilo BZ (1996) trachealess encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is an inducer of tracheal cell fates in Drosophila. Genes & Development 10: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manning G, Krasnow MA (1993) Development of the Drosophila tracheal system.. In: Bate M, AMartinez Arias A, editors. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 609–685.

- 7. Sonnenfeld M, Ward M, Nystrom G, Mosher J, Stahl S, et al. (1997) The Drosophila tango gene encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is orthologous to mammalian Arnt and controls CNS midline and tracheal development. Development 124: 4571–4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohshiro T, Saigo K (1997) Transcriptional regulation of breathless FGF receptor gene by binding of TRACHEALESS/dARNT heterodimers to three central midline elements in Drosophila developing trachea. Development 124: 3975–3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crews S, Thomas J, Goodman C (1988) The Drosophila single-minded gene encodes a nuclear protein with sequence similarity to the per gene product. Cell 15: 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ward MP, Mosher JT, Crews ST (1998) Regulation of bHLH-PAS protein subcellular localization during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development 125: 1599–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kearney JB, Wheeler SR, Estes P, Parente B, Crews ST (2004) Gene expression profiling of the developing Drosophila CNS midline cells. Developmental Biology 275: 473–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chung S, Chavez C, Andrew DJ (2011) Trachealess (Trh) regulates all tracheal genes during Drosophila embryogenesis. Developmental Biology 360: 160–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zelzer E, Wappner P, Shilo B-Z (1997) The PAS domain confers target gene specificity of Drosophila bHLH/PAS proteins. Genes & Development 11: 2079–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brankatschk M, Dickson BJ (2006) Netrins guide Drosophila commissural axons at short range. Nature Neuroscience 9: 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitchell KJ, Doyle JL, Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Tessier-Lavigne M, et al. (1996) Genetic analysis of Netrin genes in Drosophila: Netrins guide CNS commissural axons and peripheral motor axons. Neuron 17: 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris R, Sabatelli LM, Seeger MA (1996) Guidance cues at the Drosophila CNS midline: identification and characterization of two Drosophila Netrin/UNC-6 homologs. Neuron 17: 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kidd T, Brose K, Mitchell KJ, Fetter RD, Tessier-Lavigne M, et al. (1998) Roundabout controls axon crossing of the CNS midline and defines a novel subfamily of evolutionarily conserved guidance receptors. Cell 92: 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS (1999) Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell 96: 785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Battye R, Stevens A, Jacobs JR (1999) Axon repulsion from the midline of the Drosophila CNS requires slit function. Development 126: 2475–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seeger MA, Tear G, Ferresmarco D, Goodman CS (1992) Commissureless - a gene in Drosophila that is essential for growth cone guidance towards the midline. Molecular Biology of the Cell 3: A190–A190. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kidd T, Russell C, Goodman CS, Tear G (1998) Dosage-sensitive and complementary functions of roundabout and commissureless control axon crossing at the midline. Neuron 20: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seeger M, Tear G, Ferresmarco D, Goodman CS (1993) Mutations affecting growth cone guidance in Drosophila - genes necessary for guidance toward or away from the midline. Neuron 10: 409–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tear G, Harris R, Sutaria S, Kilomanski K, Goodman CS, et al. (1996) commissureless controls growth cone guidance across the CNS midline in Drosophila and encodes a novel membrane protein. Neuron 16: 501–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wheeler SR, Kearney JB, Guardiola AR, Crews ST (2006) Single-cell mapping of neural and glial gene expression in the developing Drosophila CNS midline cells. Developmental Biology 294: 509–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]