Abstract

Osteoblast apoptosis plays an important role in bone development and maintenance, and is in part responsible for osteoporosis in sex steroid deficiency, glucocorticoid excess, and aging. Although Bcl2 subfamily proteins, including Bcl2 and Bcl-XL, inhibit apoptosis, the physiological significance of Bcl2 in osteoblast differentiation has not been fully elucidated. To investigate this, we examined Bcl2-deficient (Bcl2−/−) mice. In Bcl2−/− mice, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive osteoblasts were reduced in number, while terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL)-positive osteoblasts were increased. Unexpectedly, osteoblast differentiation was accelerated in Bcl2−/− mice as shown by the early appearance of osteocalcin-positive osteoblasts. Osteoblast differentiation was also accelerated in vitro when primary osteoblasts were seeded at a high concentration to minimize the reduction of the cell density by apoptosis during culture. FoxO transcription factors, whose activities are negatively regulated through the phosphorylation by Akt, play important roles in multiple cell events, including proliferation, death, differentiation, longevity, and stress response. Expressions of FasL, Gadd45a, and Bim, which are regulated by FoxOs, were upregulated; the expression and activity of FoxOs were enhanced; and the phosphorylation of Akt and that of FoxO1 and FoxO3a by Akt were reduced in Bcl2−/− calvariae. Further, the levels of p53 mRNA and protein were increased, and the expression of p53-target genes, Pten and Igfbp3 whose proteins inhibit Akt activation, was upregulated in Bcl2−/− calvariae. However, Pten but not Igfbp3 was upregulated in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts, and p53 induced Pten but not Igfbp3 in vitro. Silencing of either FoxO1 or FoxO3a inhibited and constitutively-active FoxO3a enhanced osteoblast differentiation. These findings suggest that Bcl2 deficiency induces and activates FoxOs through Akt inactivation, at least in part, by upregulating Pten expression through p53 in osteoblasts, and that the enhanced expression and activities of FoxOs may be one of the causes of accelerated osteoblast differentiation in Bcl2−/− mice.

Introduction

Osteoblast apoptosis plays an important role in bone development and maintenance. All major regulators of bone metabolism, including estrogen, androgen, parathyroid hormone (PTH), locally produced factors like interleukin 6 (IL-6)-type cytokine, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), Wnts, PTH-related peptide (PTHrP), mechanical forces, and oxidative stress, modulate osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis [1]. It is estimated that 60–80% of osteoblasts that originally assembled at the resorption pit die by apoptosis. Further, bone loss caused by sex steroid deficiency, glucocorticoid excess, or aging is due in part to osteoblast apoptosis, and PTH, bisphosphonate, and calcitonin exert anabolic action on bone by inhibiting osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis, [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Bcl2 subfamily proteins, including Bcl2 and Bcl-XL, inhibit apoptosis through prevention of the release of caspase activators from mitochondria by inhibiting Bax subfamily proteins [10]. Thus, the bone loss caused by sex steroid deficiency, glucocorticoid excess, or aging might be inhibited by Bcl2; however, the physiological significance of Bcl2 in osteoblast differentiation and bone development and maintenance has not been fully investigated.

Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) by a number of growth factors, including insulin and insulin-like growth factors (IGF), results in the production of phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3), and this in turn causes localization of the kinase Akt to the plasma membrane. At the plasma membrane, Akt can be phosphorylated by Pdk1 and mTORC2 (consisting of the kinase mTOR, Rictor, Sin1, and mLST8 complex), leading to its full activation. Activated Akt phosphorylates a subset of targets, including the FoxO family of transcription factors, which include FoxO1, FoxO3a, and FoxO4. Phosphorylated FoxO factors interact with the adaptor 14-3-3, which promotes relocalization to the cytoplasm. Oxidative stress opposes nuclear export by alternative phosphorylation of FoxO factors. Phosphorylation mediated by JNK and Mst1, which are activated by oxidative stress, promotes translocation to the nucleus [11], [12], [13]. p53, which senses various intrinsic and extrinsic stress signals, induces the negative regulators, including Igfbp3 and Pten, in the PI3K-Akt pathway to shut down cell growth and division to avoid the introduction of infidelity into the process of cell growth and division [14], [15]. Igfbp3 binds to free IGF-1 and prevents it from binding to the IGF-1 receptors, and Pten reverses the effects of PI3K by dephosphorylating PIP3 [16].

Recently, FoxO-dependent oxidative defense was shown to be important for bone formation and bone mass homeostasis [17], [18]. FoxOs inhibit osteoblast apoptosis through the suppression of oxidative stress [17]. Further, FoxO1 regulates osteoblast proliferation through the interaction with ATF4, a transcription factor regulating amino acid import, as well as through the suppression of p19ARF and p16 and downstream activation of their target protein p53 [18]. Further, FoxO1 has been shown to regulate osteoblast differentiation [19], [20].

The previous reports showed that osteoblast apoptosis was unchanged or increased, and osteoblast differentiation was unchanged or inhibited in Bcl2-deficient (Bcl2−/−) primary osteoblasts compared with wild-type primary osteoblasts in vitro [21], [22]. However, we found that osteoblast differentiation is inhibited in osteoblast-specific Bcl2 transgenic mice [23]. Further, we found that differentiation of the primary osteoblasts from Bcl2 transgenic mice is also inhibited in vitro, but that it is affected by apoptosis, because osteoblast apoptosis reduces cell density and leads to the deceleration of osteoblast differentiation [23]. Thus, we examined osteoblast proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation in the bone tissues of Bcl2−/− mice to evaluate the physiological roles of Bcl2 in osteoblasts. Contrary to the previous reports, osteoblast differentiation was accelerated in Bcl2−/− mice. The differentiation of Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts was also accelerated in vitro, when the cells were seeded at a high concentration to minimize the reduction of the cell density by apoptosis during culture. Thus, we further pursued the mechanism of enhanced osteoblast differentiation in vivo using bone tissues. Here, we show that the deletion of Bcl2 accelerated osteoblast differentiation, at least in part, through the Akt-FoxO pathway.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Prior to the study, all experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. (Permit Number: 0906170767-4).

Animal Study

Bcl2−/− mice were generated as previously described [24]. Briefly, ES cells derived from 129/Ola were injected into the blastocysts recovered from the mating of B6C3F1 (C57BL/6 x C3H F1) with C57BL/6, and the chimeric mice were mated with ICR. Wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice were obtained by brother-sister mating of heterozygous mice.

Histological Analysis

The bone histomorphometric analysis was performed by measuring the area and perimeter of trabecular bone of femurs at 2 weeks of age with Image J using the H-E stained paraffin-embedded sections. For histological analyses of the long bones, mice were sacrificed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, and the long bones were decalcified in 10% EDTA (pH7.4) and embedded in paraffin. Sections (3–7 µm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) or stained for TUNEL using the ApopTag® system (Intergen, Burlington, MA), or subjected to in situ hybridization using Col1a1, osteopontin, and osteocalcin probes [25]. For the BrdU incorporation study, mice of 2 weeks of age were injected intraperitoneally with 100 µg BrdU/gram body weight and sacrificed 1 hour later. Sections were stained with the BrdU staining kit (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). In the counting of TUNEL-positive or BrdU-positive osteoblastic cells, only the cells in the distal primary spongiosa of femurs, which were recognized as osteoblastic cells from the morphology and attachment to the trabecular bone, were counted.

Real-time RT-PCR and Western Blot Analyses

Total RNA was extracted using ISOGEN (Wako, Osaka, Japan), and real-time RT-PCR was performed as previously described [26]. Primer sequences are shown in Table S1. We normalized the values to that of Gapdh. Western blot analysis was performed using the following antibodies: anti-Akt, anti-phosphorylated Akt, anti-FoxO1, anti-FoxO3a, anti-phosphorylated FoxO1 (Thr24)/FoxO3a (Thr32), anti-JNK, anti-phosphorylated JNK, anti-Mst1, and anti-phosphorylated Mst1 antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); anti-phosphorylated FoxO3a (S207) antibody (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan); and anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

In situ Hybridization

For in situ hybridization, we prepared digoxigenin-11-UTP-labeled single-stranded RNA probes using a DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche Biochemica) according to the manufacturer's instructions. We used a 0.32 kb fragment of Col1a1 cDNA [27], a 1.2 kb fragment of mouse osteopontin cDNA [28], and a 0.47 kb fragment of mouse osteocalcin cDNA [29] to generate antisense and sense probes. We carried out hybridization as previously described [28] and counterstained the sections with methyl green.

Cell Culture Experiments

Primary osteoblasts were isolated from newborn calvaria by sequential digestion with 0.1% collagenase A and 0.2% dispase. Osteoblastic cells from the third to fifth fraction were pooled, plated on 48-well plates at a density of 2.5×104/well and 24-well plates at a density of 5×104/well, and used for MTT, osteoblast differentiation, and TUNEL assays. To examine osteoblast differentiation, staining for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralization was performed as previously described [30]. Quantification of mineralization was performed using VHX-1000 (KEYENCE) and Image J. TUNEL-positive cells were detected using the ApopTag® system (Intergen, Burlington, MA). FoxO3a-AAA triple mutant (FoxO3a-TM) adenovirus was a gift from K. Walsh (Boston University Medical School) [31]. In FoxO3a-TM, the three phosphorylation sites, Thr-32, Ser-253, and Ser-315, were replaced by alanine residues. MC3T3-E1 cells were infected with the retrovirus vector (pSIREN-RetroQ, Takara Bio, Inc. Otsu, Japan) expressing each shRNA for GFP, FoxO1, and FoxO3a, and cultured for 3 days in the presence of puromycin. BMP2 (100 ng/ml) was added to the medium at confluence. A p53−/− osteoblast cell line, which was established from p53−/− calvarial cells, was infected with human p53-expressing retrovirus or empty retrovirus. Retrovirus was constructed by inserting full length human p53 cDNA into pDON-5 (Takara Bio, Inc.).

Reporter Assay

Primary osteoblasts from wild-type and Bcl2−/− mice were transfected with the Gadd45a promoter construct [32] and pRL-CMV by FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan). Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity using pRL-CMV (Promega, Madison, WI).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test. Ekuseru-Toukei 2010 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

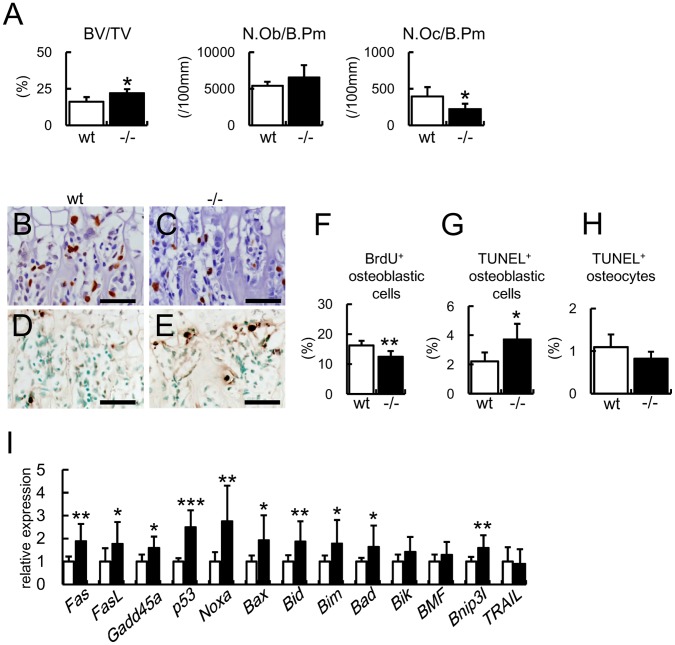

Increase in Bone Mass and Osteoblast Apoptosis in Bcl2−/− Mice

As Bcl2−/− mice died at approximately 2–3 weeks of age, bone histomorphometric analysis was performed on the trabecular bone of femurs at 2 weeks of age (Fig. 1A). The bone volume was increased in Bcl2−/− mice and the density of osteoblasts in Bcl2−/− mice was similar to that in wild-type mice. In contrast, the density of osteoclasts was reduced in Bcl2−/− mice. The percentage of BrdU-positive osteoblastic cells in Bcl2−/− mice was less than that in wild-type mice (Fig. 1B, C, F), while the percentage of TUNEL-positive osteoblastic cells was increased in Bcl2−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1D, E, G). The percentage of TUNEL-positive osteocytes in Bcl2−/− mice was similar to that in wild-type mice (Fig. 1H). The expression of apoptosis-related genes, including Fas, FasL, p53, Noxa, Bax, Bid, Bim, Bad, Bnip3l, was increased in calvaria of Bcl2−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1I).

Figure 1. Bone morphometric analysis, BrdU and TUNEL staining, and real-time RT-PCR analysis of apoptosis-related genes in Bcl2−/− mice.

(A) Bone histomorphometric analysis. The trabecular bone volume (bone volume/tissue volume, BV/TV), number of osteoblasts (N.Ob/B.Pm), and number of osteoclasts (N.Oc/B.Pm) were compared in femurs between 6 wild-type and 4 Bcl2−/− mice at 2 weeks of age. B.Pm, bone perimeter. (B–H) BrdU labeling (B, C) and TUNEL staining (D, E) of sections of femurs from wild-type mice (B, D) and Bcl2−/− mice (C, E). Bars = 50 µm. BrdU-positive osteoblastic cells (F), TUNEL-positive osteoblastic cells (G), and TUNEL-positive osteocytes (H) were counted and shown as a percentage of the number of osteoblastic cells or osteocytes. wild-type mice, n = 7; Bcl2−/− mice, n = 5 in F. wild-type mice, n = 8; Bcl2−/− mice, n = 5 in G and H. (I) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of apoptosis-related genes. RNA was directly extracted from newborn calvariae of wild-type and Bcl2−/− mice. wild-type mice, n = 6; Bcl2−/− mice, n = 15. *vs. wild-type mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

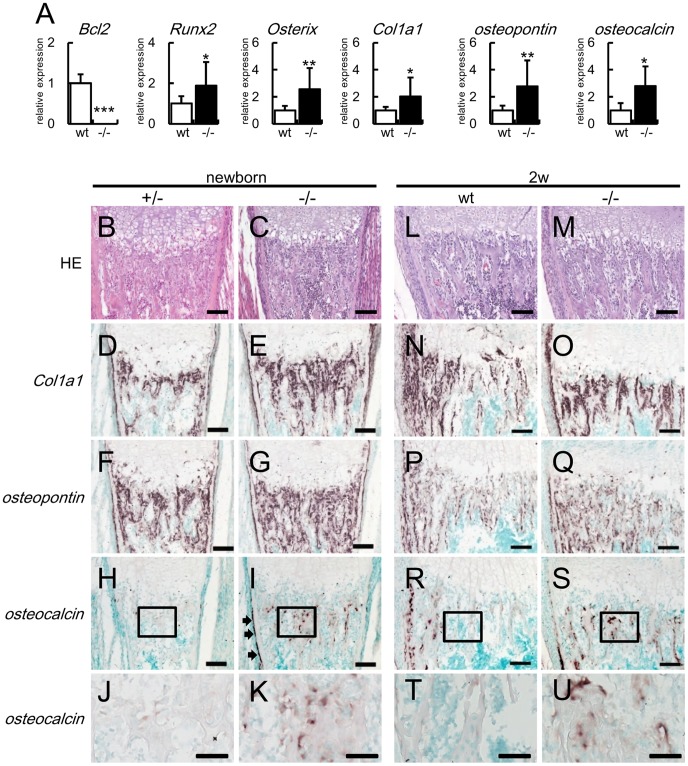

Osteoblast Differentiation was Accelerated in Bcl2−/− Mice

We examined the expression of osteoblast differentiation marker genes, including Runx2, Osterix, Col1a1, osteopontin, and osteocalcin, in calvariae of Bcl2−/− mice by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Runx2 and Osterix are upregulated in preosteoblasts, Col1a1 and osteopontin are upregulated in immature osteoblasts, and osteocalcin is upregulated in mature osteoblasts [33], [34]. The expressions of all of these markers were increased in Bcl2−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2A). Further, we examined osteoblast differentiation by in situ hybridization at birth and 2 weeks of age. Col1a1-expressing cells and osteopontin-expressing cells were increased at birth and 2 weeks of age in Bcl2−/− mice compared with wild-type mice, reflecting the increased bone volume and similar osteoblast density compared with those in wild-type mice (Fig. 1A, 2D–G, N–Q). In wild-type mice, there were few osteocalcin-expressing cells and its expression level was low at birth, but both the number and expression level were increased in the bone collar and the trabecular bone near the bone collar but not in the other trabecular bone at 2 weeks of age (Fig. 2H, J, R, T). In Bcl2−/− mice, however, osteocalcin-expressing cells were apparently present in both the bone collar and trabecular bone at birth and they were observed in the entire trabecular bone at 2 weeks of age (Fig. 2I, K, S, U). These findings indicate that osteoblast differentiation was accelerated in Bcl2−/− mice.

Figure 2. Expression of bone matrix protein genes in Bcl2−/− mice.

(A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of Bcl2, Runx2, Osterix, Col1a1, osteopontin, and osteocalcin. RNA was directly extracted from newborn calvariae of wild-type (wt) and Bcl2−/− mice. The values of wild-type mice were defined as 1, and relative levels are shown. wild-type mice, n = 6; Bcl2−/− mice, n = 15. *vs. wild-type mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (B–U) In situ hybridization analysis of Col1a1, osteopontin, and osteocalcin. The sections of femurs from Bcl2+/− mice (B, D, F, H, J), Bcl2−/− mice (C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U), and wild-type mice (L, N, P, R, T) at birth (B–K) and at 2 weeks of age (L–U) were stained with H–E (B, C, L, M) or hybridized with Col1a1 (D, E, N, O), osteopontin (F, G, P, Q), and osteocalcin (H–K, R–U) probes. Boxed regions in H, I, R, and S are magnified in J, K, T, and U, respectively. Arrows in I indicate the appearance of osteocalcin-expressing cells in the bone collar. Similar results were obtained in two newborn mice and three 2-week-old mice in each genotype and representative data are shown. In situ hybridization using the sense probes showed no significant signals (data not shown). Bars: 100 µm (B–I, L–S); 50 µm (J, K, T, U).

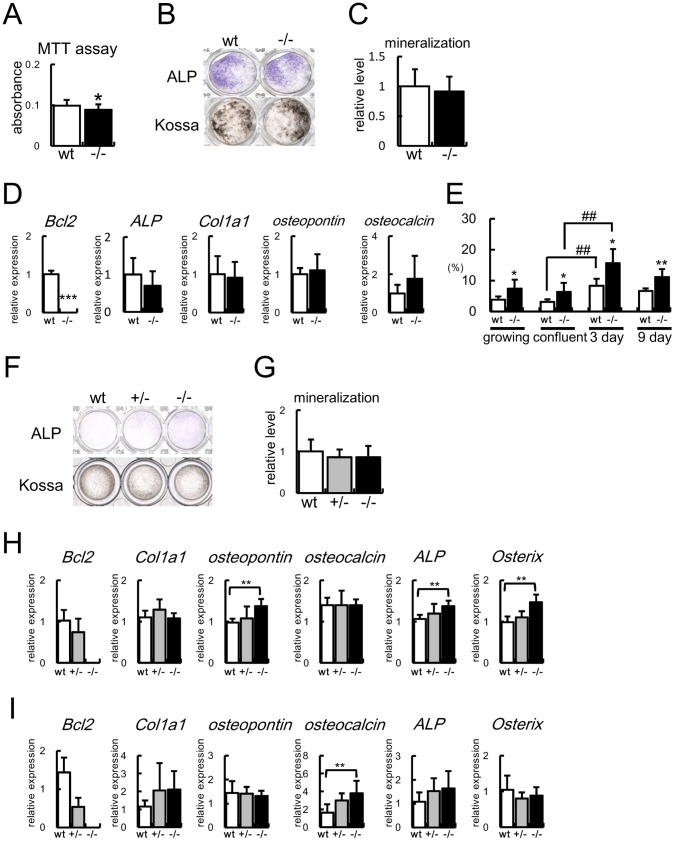

Proliferation, Differentiation, and Apoptosis of Bcl2−/− Osteoblasts in vitro

MTT assays showed that proliferation of Bcl2−/− osteoblasts was reduced compared with that of wild-type osteoblasts (Fig. 3A). Primary osteoblasts isolated from Bcl2−/− mice were seeded at a concentration of 2.5×104/cm2, ALP activity and the osteoblast marker gene expression were examined after 6 days, and mineralization was examined after 17 days (Fig. 3B–D). The ALP activity, mineralization, and the expression of ALP, Col1a1, osteopontin, and osteocalcin were similar to those from wild-type mice (Fig. 3B–D). However, apoptosis of the proliferating osteoblasts should affect the results of the MTT assay. Further, apoptosis during culture should affect osteoblast differentiation, because osteoblast differentiation in vitro is largely dependent on the cell density [23]. Thus, we examined apoptosis during osteoblast proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Osteoblast apoptosis was significantly increased not only during proliferation but also during differentiation in Bcl2−/− osteoblasts (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. Analyses of proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts.

(A) MTT assay. Primary osteoblasts from calvariae of 4 wild-type and 3 Bcl2−/− mice were cultured for 3 days, the cells were replated, and MTT assay was performed 24 hrs later. n = 16. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments and representative data are shown. (B–D) Differentiation of primary osteoblasts from Bcl2−/− mice. Primary osteoblasts were prepared from newborn calvariae of wild-type and Bcl2−/− mice, and ALP and von Kossa staining (B), quantification of mineralization (C), and real-time RT-PCR analysis (D) were performed. Primary osteoblasts were seeded at a concentration of 2.5×104/cm2 (day 0). 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate were added at day 3, ALP activity and the osteoblast marker gene expression were examined at day 6, and mineralization was examined at day 17. The value of primary osteoblasts from wild-type mice was set as 1 and the relative level is shown. n = 3. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and representative data are shown. (E) Frequencies of TUNEL-positive cells during culture. Primary osteoblasts from calvariae of 6 wild-type and 10 Bcl2−/− mice were stained for TUNEL before confluence, at confluence, and at 3 and 9 days after confluence. n = 4−5. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments and representative data are shown. (F–I) Differentiation of primary osteoblasts from calvariae of Bcl2−/− mice. Primary osteoblasts were seeded at a concentration of 2×105/cm2 (day 0), 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid and 10mM β-glycerophosphate were added at day 1, ALP activity was examined at day 2 (F), mineralization was examined at day 9 (G), and the osteoblast marker gene expression was examined at day 2 (H) and 9 (I) by real-time RT-PCR. n = 7 in G; n = 5 in H; n = 10−12 in I. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and representative data are shown. *vs. wild-type primary osteoblasts. *P<0.05; **, ##P<0.01; ***p<0.001.

To minimize the reduction of cell density by apoptosis, primary osteoblasts isolated from wild-type, Bcl2+/−, and Bcl2−/− mice were seeded at a higher concentration (2×105/cm2) and ALP activity and the osteoblast marker gene expression were examined after 2 days (Fig. 3F, H). ALP activity and the expression of osteopontin, ALP, and Osterix were increased in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts compared with those in wild-type primary osteoblasts. After 8 days, the mineralization was similar between wild-type and Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts, but osteocalcin mRNA was increased in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts (Fig. 3F, G, I). Although ALP activity was slightly increased in Bcl2+/− primary osteoblasts compared with wild-type primary osteoblasts, the mineralization and the osteoblast marker gene expression were similar between Bcl2+/−and wild-type primary osteoblasts (Fig. 3F–I).

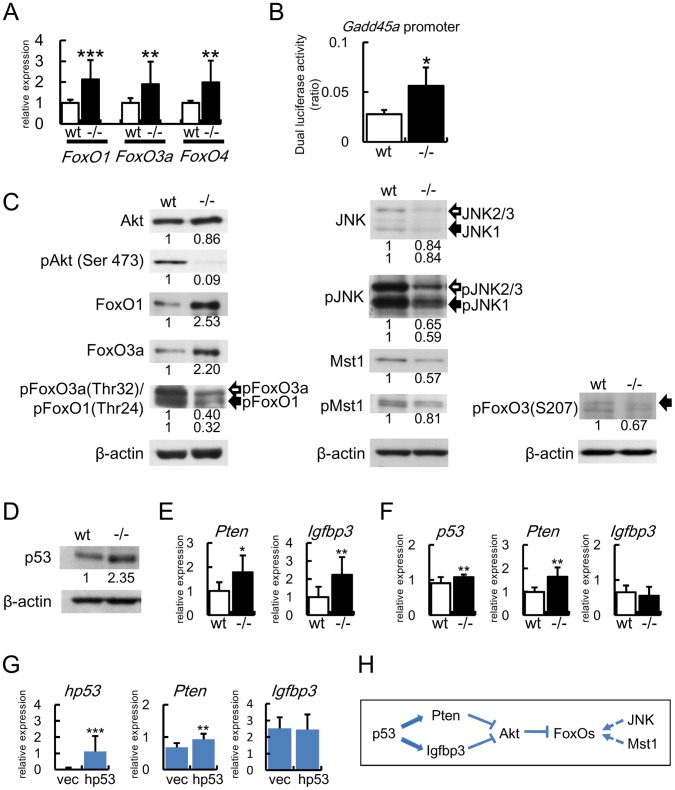

Upregulation and Activation of FoxOs in Bcl2−/− Calvariae

As Bcl2-deficiency enhanced osteoblast differentiation in vivo, we examined the mechanism of the accelerated osteoblast differentiation in vivo by directly analyzing the newborn calvariae. The expressions of FasL, Gadd45a, and Bim, which are regulated by FoxOs, were upregulated in Bcl2−/− calvariae (Fig. 1I). As FoxO1 enhances osteoblast differentiation [19], [20], FoxOs might be involved in enhanced osteoblast differentiation in Bcl2−/− mice. Thus, we first examined the expression and activity of FoxOs. The expressions of FoxO1, FoxO3a, and FoxO4 mRNAs were increased in Bcl2−/− calvariae compared with wild-type calvariae, and the promoter activity of Gadd45a was enhanced in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts compared with wild-type primary osteoblasts (Fig. 4A, B). FoxO proteins are inactivated through the phosphorylation by Akt. Akt itself is activated by phosphorylation (Fig. 4H) [11], [12], [13]. Thus, we examined the activation state of Akt and FoxOs by examining their phosphorylation. The phosphorylation of Akt was markedly reduced in Bcl2−/− calvariae compared with wild-type calvariae, although similar levels of Akt protein were detected (Fig. 4C). Protein levels of FoxO1 and FoxO3a were increased, whereas the phosphorylation of Thr24 in FoxO1 and that of Thr32 in FoxO3, which are phosphorylated by Akt, were reduced (Fig. 4C). These findings indicate that FoxO proteins were activated by the inactivation of Akt. FoxO proteins are also activated through the phosphorylation by JNK and Mst1, and JNK and Mst1 are activated by phophorylation (Fig. 4H) [11], [12]. Protein levels of JNK and Mst1 and the levels of their phosphorylated forms were mildly reduced, and the phosphorylation of S207 in FoxO3a, which is phosphorylated by JNK and Mst1, was also mildly reduced in Bcl2−/− calvariae compared with wild-type calvariae. These findings indicate that FoxO proteins were not activated by JNK and Mst1. These findings indicate that FoxO proteins were activated in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts through the reduction in Akt phosphorylation but not through the increase in JNK and Mst1 phosphorylation (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4. Expression and activation of FoxOs in Bcl2−/− calvariae.

(A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the expression of FoxOs. RNA was directly extracted from newborn calvariae of wild-type and Bcl2−/− mice. wild-type mice, n = 6; Bcl2−/− mice, n = 15. *vs. wild-type mice, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (B) Reporter assay of Gadd45a promoter using wild-type and Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments and representative data are shown. (C, D) Western blot analysis. Protein was extracted from newborn calvariae of wild-type and Bcl2−/− mice. The intensities of the bands were normalized against each β-actin, the normalized values in wild-type mice were set as 1, and relative levels are shown. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and representative data are shown. (E) Real-time RT-PCR analysis. RNA was directly extracted from calvariae of wild-type and Bcl2−/− newborn mice. wild-type mice, n = 6; Bcl2−/− mice, n = 15. *vs. wild-type mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (F) p53, Pten, and Igfbp3 expression in primary osteoblasts. The cDNA in Fig. 3I was used for real-time PCR analysis. n = 10−12. *vs. wild-type primary osteoblasts. **P<0.01. (G) Induction of Pten by p53. p53−/− osteoblasts were infected with p53-expressing retrovirus or empty retrovirus. Next day, the cells were plated at the concentration of 1.5×105/well in 48 well plates (day 0). 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid and 10mM β-glycerophosphate were added at day 1, and mRNA was extracted at day 4. The expression of p53, Pten, and Igfbp3 was examined by real-time RT-PCR. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments and representative data are shown. n = 12−13. *vs. empty retrovirus. **P<0.01, ***p<0.001. (H) Schematic presentation of the signaling pathway for FoxO activation. p53 induces Pten mRNA and Igfbp3 mRNA. Pten and Igfbp3 inhibit Akt activation. Akt inhibits the activation of FoxOs. Activation of JNK and Mst1 activate FoxOs. p53 failed to induce Igfbp3 in vitro (G). Dotted arrows indicate that the activation did not occur in Bcl2−/− mice (C).

We further examined why Akt phosphorylation was inhibited in Bcl2−/− calvariae. p53 has been shown to induce the expression of Pten and Igfbp3, whose proteins inhibit Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4H) [14], [15], [16]. As p53 mRNA expression was increased in Bcl2−/− calvariae (Fig. 1I), we confirmed that the protein level of p53 was also increased in Bcl2−/− calvariae (Fig. 4D). Further, Pten and Igfbp3 expression was increased in Bcl2−/− calvariae (Fig. 4E).

In the culture of primary osteoblasts, the expression of p53 and Pten but not Igfbp3 was increased in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts compared with those in wild-type primary osteoblasts (Fig. 4F). To examine whether p53 induces Pten and Igfbp3, we introduced p53 to p53−/− osteoblast cell line. Pten mRNA but not Igfbp3 mRNA was induced by p53 (Fig. 4G). Further, FoxO3a mRNA was not induced by p53 (data not shown). These findings suggest that Akt phosphorylation was reduced, at least in part, by the induction of Pten through upregulated p53 (Fig. 4C–H).

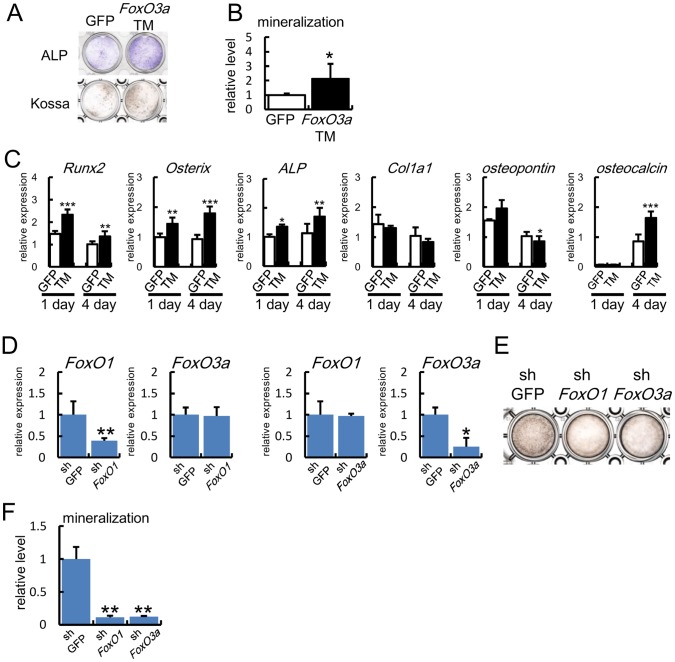

FoxOs Enhanced Osteoblast Differentiation

To examine whether FoxOs are able to enhance osteoblast differentiation, a constitutively active form of FoxO3a (FoxO3a-TM) was introduced into primary osteoblasts (Fig. 5A–C). FoxO3a-TM enhanced ALP activity, mineralization, and the expression of Runx2, Osterix, ALP, and osteocalcin. Further, retroviral introduction of shRNA of either FoxO1 or FoxO3a into MC3T3-E1 cells reduced mineralization (Fig. 5D–F). These findings suggest that FoxOs may be involved in the enhanced osteoblast differentiation in Bcl2−/− mice.

Figure 5. Induction of osteoblast differentiation by FoxOs.

(A–C) Induction of osteoblast differentiation by FoxO3aTM. Primary osteoblasts from calvariae of wild-type mice were infected with adenovirus expressing GFP or FoxO3aTM, and ALP staining at 2 days and von Kossa staining at 6 days after infection (A), quantification of mineralization (B), and osteoblast marker gene expression (C) are shown. The value in GFP-introduced cells was set as 1 and the relative level is shown in B. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and representative data are shown. (D–F) Inhibition of the mineralization of MC3T3-E1 cells by shFoxO1 and shFoxO3a. MC3T3-E1 cells were infected with retrovirus expressing GFP, shFoxO1, or shFoxO3a, and cultured in the presence of BMP2 (100ng/ml). The expression of FoxO1 and FoxO3a was examined by real-time RT-PCR (D) and mineralization was examined by von Kossa staining (E) and its quantification (F) after culture for 2 weeks. The value in shGFP-introduced cells was set as 1 and the relative levels are shown in F. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and representative data are shown.

Discussion

The proliferation was reduced and apoptosis was increased, but the differentiation was accelerated in osteoblasts and mature osteoblasts were increased in Bcl2−/− mice. Therefore, our findings indicate that bone mass was increased in Bcl2−/− mice not only due to the decrease in osteoclast number but also due to the acceleration of osteoblast differentiation.

The finding that osteoblast differentiation was accelerated in Bcl2−/− mice was unexpected, because previous reports indicated that osteoblast differentiation was unaffected or inhibited in Bcl2−/− mice based on the data of in vitro differentiation of Bcl2−/− osteoblasts [21], [22]. The culture of primary osteoblasts seeded at the concentration of 2.5×104/cm2 also showed that the differentiation of Bcl2−/− osteoblasts was unaffected in vitro. However, the culture of primary osteoblasts seeded at the higher concentration (2×105/cm2) showed that the differentiation of Bcl2−/− osteoblasts was accelerated. We recently reported that overexpression of Bcl2 inhibits osteoblast differentiation in vivo and in vitro [23]. However, the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation by over-expressed Bcl2 in vitro was dependent on the cell density seeded, because overexpression of Bcl2 enhanced osteoblast differentiation by increasing cell density through the inhibition of apoptosis in vitro [23]. Therefore, the discrepancy in osteoblast differentiation in Bcl2−/− mice between our data and previous reports was likely to be explained by the reduction in the cell density during culture due to the increased apoptosis in Bcl2−/− osteoblasts. Indeed, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the decreased number and dysfunction of osteoclasts in Bcl2−/− mice indirectly affected the osteoblast differentiation rather than in a cell autonomous manner.

In Bcl2−/− calvariae, mRNAs for FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4, and their target genes, including FasL, Gadd45a, and Bim, were upregulated, and the promoter activity of Gadd45a was enhanced in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts. Further, the phosphorylation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a by Akt was reduced due to the suppression of Akt, at least in part, through the upregulation of Pten and Igfbp3, while the phosphorylation of FoxO3a by JNK and Mst1 was not enhanced, suggesting that FoxOs were activated in Bcl2−/− osteoblasts through the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. As Pten and Igfbp3 are target genes of p53 [14], [15], the activation of FoxOs by Akt may be dependent on p53 but not Bcl2 itself. The expressions of Pten and Igfbp3 were upregulated in Bcl2−/− calvarial tissues, whereas the expression of Pten but not Igfbp3 was upregulated in Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts. Further, introduction of p53 induced the expression of Pten but not Igfbp3. These findings indicate that upregulation of p53 is sufficient for Pten induction in vivo and in vitro, but that it is not sufficient for Igfbp3 induction in vitro. Therefore, the molecules, which cooperate with p53 for Igfbp3 induction, may be insufficient in vitro. Indeed, it is possible that other cell types including lymphocytes, in which apoptosis is accelerated [24], [43], contributed to the induction of Igfbp3 in Bcl2−/− calvarial tissues. p53 also inhibits FoxO3a activity by inducing SGK, by directly inhibiting the transcriptional activity, or by inducing FoxO3a degradation through Mdm2 [35], [36], [37]. Therefore, p53 seems to regulate FoxO activity positively or negatively depending on the cell type and cell conditions. We also showed the transcriptional upregulation of FoxOs in Bcl2−/− calvariae. Recently, it has been shown that FoxO3a is a target gene of p53 [38], [39]. Further, FoxO1 and FoxO4 genes are regulated by FoxO3a [40]. Therefore, the increased p53 may be responsible for the upregulation of FoxO1, FoxO3a, and FoxO4 mRNA expression in Bcl2−/− calvariae. However, the introduction of p53 failed to induce FoxO3a mRNA in vitro (data not shown). Therefore, the mechanism of the increase of FoxOs mRNA in Bcl2−/− mice still remains to be clarified.

p53 has been shown to inhibit osteoblast differentiation [41], [42]. However, it is evident in vitro but not in vivo, because the calvarial bone volume is mildly reduced in p53−/− mice compared with wild-type mice [41]. Since the deletion of p53 enhances proliferation and inhibits apoptosis, p53 deletion should increase the cell density in culture, leading to the acceleration of osteoblast differentiation in vitro, because osteoblast differentiation is dependent on the cell density in vitro [23]. Similarly, the increase in osteoblast number due to increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis should also lead to an increase in bone formation in p53−/− mice as previously reported [41]. Therefore, the function of p53 in osteoblast differentiation needs to be further investigated.

Although osteoblast proliferation was not examined in vivo in previously reported Bcl2−/− mice [21], [22], we showed that the number of proliferating osteoblasts was reduced in Bcl2−/− mice. Further, we observed a reduction in the number of Bcl2−/− primary osteoblasts in the MTT assay, suggesting that Bcl2 enhances osteoblast proliferation. However, it could also have been caused by increased apoptosis during culture. Previous reports showed that Bcl2 inhibits cell proliferation by facilitating G0 arrest and delaying G0 to S phase transition in hematopoietic cells and fibroblasts [44], and various groups showed that p27 as well as p130 was elevated in Bcl2-overexpressing cells during arrest [45], [46], [47], [48], although overexpression of Bcl2 in myocytes promoted proliferation [49]. Thus, it is possible that the decrease in proliferating osteoblasts in Bcl2−/− mice was mostly a reflection of enhanced osteoblast differentiation, although the activation of FoxOs should have affected both proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts in Bcl2−/− mice [50].

In summary, osteoblast differentiation was enhanced in Bcl2−/− mice, at least in part, through FoxOs. FoxOs were activated through the suppression of Akt, at least in part, by upregulation of Pten through p53. Although osteoblast apoptosis is in part responsible for osteoporosis in sex steroid deficiency, glucocorticoid excess, and aging, our findings suggest that the stresses toward apoptosis may have a positive effect on osteoblast differentiation.

Supporting Information

Primer list.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Motoyama and T. Sakai for Gadd45a promoter construct, K. Ito for p53-expressing retrovirus, and C. Fukuda for secretarial assistance.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture and Technology Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC (2007) Quantifying osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis: challenges and rewards. J Bone Miner Res 22: 1492–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Brien CA, Jia D, Plotkin LI, Bellido T, Powers CC, et al. (2004) Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoblasts and osteocytes to induce their apoptosis and reduce bone formation and strength. Endocrinology 145: 1835–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, O'Brien CA, Bodenner DL, et al. (2001) Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell 104: 719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stanislaus D, Yang X, Liang JD, Wolfe J, Cain RL, et al. (2000) In vivo regulation of apoptosis in metaphyseal trabecular bone of young rats by synthetic human parathyroid hormone (1–34) fragment. Bone 27: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gohel A, McCarthy MB, Gronowicz G (1999) Estrogen prevents glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in osteoblasts in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology 140: 5339–5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC (1998) Inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and promotion of apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes by glucocorticoids. Potential mechanisms of their deleterious effects on bone. J Clin Invest 102: 274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plotkin LI, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC, et al. (1999) Prevention of osteocyte and osteoblast apoptosis by bisphosphonates and calcitonin. J Clin Invest 104: 1363–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Bellido T, Roberson P, Parfitt AM, et al. (1999) Increased bone formation by prevention of osteoblast apoptosis with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest 104: 439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tomkinson A, Reeve J, Shaw RW, Noble BS (1997) The death of osteocytes via apoptosis accompanies estrogen withdrawal in human bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 3128–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsujimoto Y (2003) Cell death regulation by the Bcl-2 protein family in the mitochondria. J Cell Physiol 195: 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daitoku H, Fukamizu A (2007) FOXO Transcription Factors in the Regulatory Networks of Longevity. J Biochem 141: 769–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hedrick SM (2009) The cunning little vixen: Foxo and the cycle of life and death. Nat Immunol 10: 1057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manning BD, Cantley LC (2007) AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating Downstream. Cell 129: 1261–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buckbinder L, Talbott R, Velasco-Miguel S, Takenaka I, Faha B, et al. (1995) Induction of the growth inhibitor IGF-binding protein 3 by p53. Nature 377: 646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stambolic V, MacPherson D, Sas D, Lin Y, Snow B, et al. (2001) Regulation of PTEN transcription by p53. Mol Cell 8: 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feng Z (2010) p53 regulation of the IGF-1/AKT/mTOR pathways and the endosomal compartment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ambrogini E, Almeida M, Martin-Millan M, Paik J-H, DePinho RA, et al. (2010) FoxO-Mediated Defense against Oxidative Stress in Osteoblasts Is Indispensable for Skeletal Homeostasis in Mice. Cell Metabol 11: 136–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rached M-T, Kode A, Xu L, Yoshikawa Y, Paik J-H, et al. (2010) FoxO1 Is a Positive Regulator of Bone Formation by Favoring Protein Synthesis and Resistance to Oxidative Stress in Osteoblasts. Cell Metabol 11: 147–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teixeira CC, Liu Y, Thant LM, Pang J, Palmer G, et al. (2010) Foxo1, a Novel Regulator of Osteoblast Differentiation and Skeletogenesis. J Biol Chem 285: 31055–31065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siqueira MF, Flowers S, Bhattacharya R, Faibish D, Behl Y, et al. (2011) FOXO1 modulates osteoblast differentiation. Bone 48: 1043–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamashita J, Datta NS, Chun Y-HP, Yang D-Y, Carey AA, et al. (2008) Role of Bcl2 in Osteoclastogenesis and PTH Anabolic Actions in Bone. J Bone Miner Res 23: 621–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nagase Y, Iwasawa M, Akiyama T, Kadono Y, Nakamura M, et al. (2009) Anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl-2 regulates the differentiation, activation, and survival of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts. J Biol Chem 284: 36659–36669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moriishi T, Maruyama Z, Fukuyama R, Ito M, Toshihiro Miyazaki, et al. (2012) Overexpression of Bcl2 in osteoblasts inhibits osteoblast differentiation and induces osteocyte apoptosis. PLoS ONE. 7(6): e40143 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040143. Epub 2012 Jun 29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kamada S, Shimono A, Shinto Y, Tsujimura T, Takahashi T, et al. (1995) bcl-2 deficiency in mice leads to pleiotropic abnormalities: accelerated lymphoid cell death in thymus and spleen, polycystic kidney, hair hypopigmentation, and distorted small intestine. Cancer Res 55: 354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inada M, Yasui T, Nomura S, Miyake S, Deguchi K, et al. (1999) Maturational disturbance of chondrocytes in Cbfa1-deficient mice. Dev Dyn 214: 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshida CA, Yamamoto H, Fujita T, Furuichi T, Ito K, et al. (2004) Runx2 and Runx3 are essential for chondrocyte maturation, and Runx2 regulates limb growth through induction of Indian hedgehog. Genes Dev 18: 952–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Metsäranta M, Toman D, Crombrugghe BD, Vuorio E (1991) Specific hybridization probes for mouse type I,II,III and IX collagen mRNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1089: 241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nomura S, Hirakawa K, Nagoshi J, Hirota S, Kim HM, et al. (1993) Method for detecting the expression of bone matrix protein by in situ hybridization using decalcified mineralized tissue. Acta Histochem Cytochem 26: 303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirota S, Takaoka K, Hashimoto J, Nakase T, Takemura T, et al. (1994) Expression of mRNA of murine bone-related proteins in ectopic bone induced by murine bone morphogenetic protein-4. Cell Tissue Res. 277: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, et al. (1997) Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell 89: 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skurk C, Izumiya Y, Maatz H, Razeghi P, Shiojima I, et al. (2005) The FOXO3a transcription factor regulates cardiac myocyte size downstream of AKT signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 20814–20823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Furukawa-Hibi Y, Yoshida-Araki K, Ohta T, Ikeda K, Motoyama N (2002) FOXO forkhead transcription factors induce G(2)-M checkpoint in response to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 26 277(30): 26729–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maruyama Z, Yoshida CA, Furuichi T, Amizuka N, Ito M, et al. (2007) Runx2 determines bone maturity and turnover rate in postnatal bone development and is involved in bone loss in estrogen deficiency. Dev Dyn 236(7): 1876–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maes C, Kobayashi T, Selig MK, Torrekens S, Roth SI, et al. (2010) Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell 17 19(2): 329–44 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. You H, Jang Y, You-Ten AI, Okada H, Liepa J, et al. (2004) p53-dependent inhibition of FKHRL1 in response to DNA damage through protein kinase SGK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14057–14062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu W, Ma Q, Chen L, Li P, Zhang M, et al. (2009) MDM2 acts downstream of p53 as an E3 ligase to promote FOXO ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem 284: 13987–14000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miyaguchi Y, Tsuchiya K, Sakamoto K (2009) P53 negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of FOXO3a under oxidative stress. Cell Biol Int 33: 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurinna S, Stratton SA, Tsai WW, Akdemir KC, Gu W, et al. (2010) Direct activation of forkhead box O3 by tumor suppressors p53 and p73 is disrupted during liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology 52: 1023–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Renault VM, Thekkat PU, Hoang KL, White JL, Brady CA, et al. (2011) The pro-longevity gene FoxO3 is a direct target of the p53 tumor suppressor. Oncogene 30: 3207–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Essaghir A, Dif N, Marbehant CY, Coffer PJ, Demoulin JB (2009) The Transcription of FOXO Genes Is Stimulated by FOXO3 and Repressed by Growth Factors. J Biol Chem 284: 10334–10342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lengner CJ, Steinman HA, Gagnon J, Smith TW, Henderson JE, et al. (2006) Osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development are regulated by Mdm2-p53 signaling. J Cell Biol 172: 909–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang X, Kua HY, Hu Y, Guo K, Zeng Q, et al. (2006) p53 functions as a negative regulator of osteoblastogenesis, osteoblast-dependent osteoclastogenesis, and bone remodeling. J Cell Biol 172: 115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Veis DJ, Sorenson CM, Shutter JR, Korsmeyer SJ (1993) Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell 75: 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zinkel S, Gross A, Yang E (2006) BCL2 family in DNA damage and cell cycle control. Cell Death Differ 13: 1351–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Linette GP, Li Y, Roth K, Korsmeyer SJ (1996) Cross talk between cell death and cell cycle progression: BCL-2 regulates NFAT-mediated activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9545–9552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brady HJ, Gomez GG, Kirberg J, Berns AJ (1996) Bax alpha perturbs T cell development and affects cell cycle entry of T cells. EMBO J 15: 6991–7001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lind EF, Wayne J, Wang QZ, Staeva T, Stolzer A, et al. (1999) Bcl-2-Induced Changes in E2F Regulatory Complexes Reveal the Potential for Integrated Cell Cycle and Cell Death Functions. J Immunol 162: 5374–5379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vairo G, Soos TJ, Upton TM, Zalvide J, DeCaprio JA, et al. (2000) Bcl-2 retards cell cycle entry through p27(Kip1), pRB relative p130, and altered E2F regulation. Mol Cell Biol 20: 4745–4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Limana F, Urbanek K, Chimenti S, Quaini F, Leri A, et al. (2002) bcl-2 overexpression promotes myocyte proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 6257–6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lam1 EW-F, Francis RE, Petkovic M (2006) FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cell fate. Biochem Soc Trans 34: 722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primer list.

(XLSX)